Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gentry

View on Wikipedia

Gentry (from Old French genterie, from gentil 'high-born, noble') are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.[1][2] Gentry, in its widest connotation, refers to people of good social position connected to landed estates (see manorialism), upper levels of the clergy, or long established "gentle" families of noble descent, some of whom in some cases never obtained the official right to bear a coat of arms. The gentry largely consisted of landowners who could support themselves entirely from rental income or at least had a country estate; some were gentleman farmers.

In the United Kingdom gentry specifically refers to the landed gentry: the majority of the land-owning social class who typically had a coat of arms but did not hold a peerage. The adjective "patrician" ("of or like a person of high social rank")[3] describes comparable elite groups in other analogous traditional social elite strata based in cities, such as the free cities of Italy (Venice and Genoa) and the free imperial cities of Germany, Switzerland and the Hanseatic League.[a] The term "gentry" by itself, the historian Peter Coss argues, is a broad construct applied by scholars to different societies, sometimes in ways that do not fully align with historical realities. Whilst no single model perfectly fits every society, some scholars favour a unified term to describe these upper social strata.[4][5]

Historical background of social stratification in the West

[edit]

The Proto-Indo-Europeans who settled Europe, Central and Western Asia and the Indian subcontinent conceived their societies to be ordered (not divided) in a tripartite fashion, the three parts being castes.[7] Castes came to be further divided, perhaps as a result of greater specialisation.

The "classic" formulation of the caste system as largely described by Georges Dumézil was that of a priestly or religiously occupied caste, a warrior caste, and a worker caste. Dumézil divided Proto-Indo-European society into three categories: sovereignty, military and productivity (see Trifunctional hypothesis). He further subdivided sovereignty into two distinct and complementary sub-parts. One part was formal, juridical, and priestly, but rooted in this world. The other was powerful, unpredictable and also priestly, but rooted in the "other", the supernatural and spiritual world. The second main division was connected with the use of force, the military and war. Finally, there was a third group, ruled by the other two, whose role was productivity: herding, farming and crafts.

This system of caste roles can be seen in the castes which flourished on the Indian subcontinent and amongst the Italic peoples.

Examples of the Indo-European castes:

- Indo-Iranian – Brahmin/Athravan, Kshatriyas/Rathaestar, Vaishyas

- Celtic – Druids, Equites, Plebes (according to Julius Caesar)

- Slavic – Volkhvs, Voin, Krestyanin/Smerd

- Anglo-Saxon – Gebedmen (prayer-men), Fyrdmen (army-men), Weorcmen (workmen) (according to Alfred the Great)

Kings were born out of the warrior or noble class, and sometimes the priesthood class, like in India.

Medieval Christendom

[edit]

Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, convoked the First Council of Nicaea in 325, whose Nicene Creed included belief in "one holy catholic and apostolic Church". The emperor Theodosius I made Nicene Christianity the state church of the Roman Empire with the Edict of Thessalonica of 380.[8]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, there emerged no single powerful secular government in the West, but there was a central ecclesiastical power in Rome, the Catholic Church. In this power vacuum the Church rose to become the dominant power in the West for the start of this time period.

In essence, the earliest vision of Christendom was a vision of a Christian theocracy, a government founded upon and upholding Christian values, whose institutions are spread through and over with Christian doctrine. The Catholic Church's peak of authority over all European Christians and their common endeavours of the Christian community—for example, the Crusades, the fight against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula and against the Ottomans in the Balkans—helped to develop a sense of communal identity against the obstacle of Europe's deep political divisions.

The classical heritage flourished throughout the Middle Ages in both the Byzantine Greek East and Latin West. In Plato's ideal state there are three major classes (producers, auxiliaries and guardians), which was representative of the idea of the "tripartite soul", which is expressive of three functions or capacities of the human soul: "appetites" (or "passions"), "the spirited element" and "reason" the part that must guide the soul to truth. Will Durant made the case that certain prominent features of Plato's ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of "the" Medieval Church in Europe:[9]

For a thousand years Europe was ruled by an order of guardians considerably like that which was visioned by our philosopher. During the Middle Ages it was customary to classify the population of Christendom into laboratores (workers), bellatores (soldiers), and oratores (clergy). The last group, though small in number, monopolized the instruments and opportunities of culture, and ruled with almost unlimited sway half of the most powerful continent on the globe. The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority ... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church. In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 AD onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians] ... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them. ...[9]

Gaetano Mosca wrote on the same subject matter in his book The Ruling Class concerning the Medieval Church and its structure that

Beyond the fact that Clerical celibacy functioned as a spiritual discipline it also was guarantor of the independence of the Church.[10]

the Catholic Church has always aspired to a preponderant share in political power, it has never been able to monopolize it entirely, because of two traits, chiefly, that are basic in its structure. Celibacy has generally been required of the clergy and of monks. Therefore no real dynasties of abbots and bishops have ever been able to establish themselves. ... Secondly, in spite of numerous examples to the contrary supplied by the warlike Middle Ages, the ecclesiastical calling has by its very nature never been strictly compatible with the bearing of arms. The precept that exhorts the Church to abhor bloodshed has never dropped completely out of sight, and in relatively tranquil and orderly times it has always been very much to the fore.[11]

Two principal estates of the realm

[edit]The fundamental social structure in Europe in the Middle Ages was between the ecclesiastical hierarchy, nobles i.e. the tenants in chivalry (counts, barons, knights, esquires, franklins) and the ignobles, the villeins, citizens, and burgesses. The division of society into classes of nobles and ignobles, in the smaller regions of medieval Europe was inexact. After the Protestant Reformation, social intermingling between the noble class and the hereditary clerical upper class became a feature in the monarchies of Nordic countries. The gentility is primarily formed on the bases of the medieval societies' two higher estates of the realm, nobility and clergy, both exempted from taxation. Subsequent "gentle" families of long descent who never obtained official rights to bear a coat of arms were also admitted to the rural upper-class society: the gentry.

The three estates

The widespread three estates order was particularly characteristic of France:

- First estate included the group of all clergy, that is, members of the higher clergy and the lower clergy.

- Second estate has been encapsulated by the nobility. Here too, it did not matter whether they came from a lower or higher nobility or if they were impoverished members.

- Third estate included all nominally free citizens; in some places, free peasants.

At the top of the pyramid were the princes and estates of the king or emperor, or with the clergy, the bishops and the pope.

The feudal system was, for the people of the Middle Ages and early modern period, fitted into a God-given order. The nobility and the third estate were born into their class, and change in social position was slow. Wealth had little influence on what estate one belonged to. The exception was the Medieval Church, which was the only institution where competent men (and women) of merit could reach, in one lifetime, the highest positions in society.

The first estate comprised the entire clergy, traditionally divided into "higher" and "lower" clergy. Although there was no formal demarcation between the two categories, the upper clergy were, effectively, clerical nobility, from the families of the second estate or as in the case of Cardinal Wolsey, from more humble backgrounds.

The second estate was the nobility. Being wealthy or influential did not automatically make one a noble, and not all nobles were wealthy and influential (aristocratic families have lost their fortunes in various ways, and the concept of the "poor nobleman" is almost as old as nobility itself). Countries without a feudal tradition did not have a nobility as such.

The nobility of a person might be either inherited or earned. Nobility in its most general and strict sense is an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary: legitimate descendants (or all male descendants, in some societies) of nobles are nobles, unless explicitly stripped of the privilege. The terms aristocrat and aristocracy are a less formal means to refer to persons belonging to this social milieu.

Historically in some cultures, members of an upper class often did not have to work for a living, as they were supported by earned or inherited investments (often real estate), although members of the upper class may have had less actual money than merchants. Upper-class status commonly derived from the social position of one's family and not from one's own achievements or wealth. Much of the population that comprised the upper class consisted of aristocrats, ruling families, titled people, and religious hierarchs. These people were usually born into their status, and historically, there was not much movement across class boundaries. This is to say that it was much harder for an individual to move up in class simply because of the structure of society.

In many countries, the term upper class was intimately associated with hereditary land ownership and titles. Political power was often in the hands of the landowners in many pre-industrial societies (which was one of the causes of the French Revolution), despite there being no legal barriers to land ownership for other social classes. Power began to shift from upper-class landed families to the general population in the early modern age, leading to marital alliances between the two groups, providing the foundation for the modern upper classes in the West. Upper-class landowners in Europe were often also members of the titled nobility, though not necessarily: the prevalence of titles of nobility varied widely from country to country. Some upper classes were almost entirely untitled, for example, the Szlachta of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Before the Age of Absolutism, institutions, such as the church, legislatures, or social elites,[12] restrained monarchical power. Absolutism was characterized by the ending of feudal partitioning, consolidation of power with the monarch, rise of state, rise of professional standing armies, professional bureaucracies, the codification of state laws, and the rise of ideologies that justify the absolutist monarchy. Hence, Absolutism was made possible by innovations and characterized as a phenomenon of Early Modern Europe, rather than that of the Middle Ages, where the clergy and nobility counterbalanced as a result of mutual rivalry.

Gentries

[edit]Continental Europe

[edit]Baltic

[edit]From the middle of the 1860s the privileged position of Baltic Germans in the Russian Empire began to waver. Already during the reign of Nicholas I (1825–55), who was under pressure from Russian nationalists, some sporadic steps had been taken towards the russification of the provinces. Later, the Baltic Germans faced fierce attacks from the Russian nationalist press, which accused the Baltic aristocracy of separatism, and advocated closer linguistic and administrative integration with Russia.

Social division was based on the dominance of the Baltic Germans, who formed the upper classes, while the majority of the indigenous populations, called Undeutsch ("non-German"), composed the peasantry. In the Imperial census of 1897, 98,573 Germans (7.58% of total population) lived in the Governorate of Livonia, 51,017 (7.57%) in the Governorate of Curonia, and 16,037 (3.89%) in the Governorate of Estonia.[13] The social changes faced by the emancipation, both social and national, of the Estonians and Latvians were not taken seriously by the Baltic German gentry. The provisional government of Russia after 1917 revolution gave the Estonians and Latvians self-governance which meant the end of the Baltic German era in Baltics.

The Lithuanian gentry consisted mainly of Lithuanians who, due to strong ties to Poland, had been culturally Polonized. After the Union of Lublin in 1569, they became less distinguishable from Polish szlachta, though they did preserve Lithuanian national awareness.

Kingdom of Hungary

[edit]In Hungary during the late 19th and early 20th century gentry (sometimes spelled as dzsentri) were nobility without land who often sought employment as civil servants, army officers, or went into politics.[14]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

[edit]In the history of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, "gentry" is often used in English to describe the Polish landed gentry (Polish: ziemiaństwo, ziemianie, from ziemia, "land"). They were the lesser members of the nobility (the szlachta), contrasting with the much smaller but more powerful group of "magnate" families (sing. magnat, plural magnaci in Polish), the Magnates of Poland and Lithuania. Compared to the situation in England and some other parts of Europe, these two parts of the overall "nobility" to a large extent operated as different classes, and were often in conflict. After the Partitions of Poland, at least in the stereotypes of 19th-century nationalist lore, the magnates often made themselves at home in the capitals and courts of the partitioning powers, while the gentry remained on their estates, keeping the national culture alive.

From the 15th century, only the szlachta, and a few patrician burghers from some cities, were allowed to own rural estates of any size, as part of the very extensive szlachta privileges. These restrictions were reduced or removed after the Partitions of Poland, and commoner landowners began to emerge. By the 19th century, there were at least 60,000 szlachta families, most rather poor, and many no longer owning land.[15] By then the "gentry" included many non-noble landowners.

Spain and Portugal

[edit]In Spanish nobility and former Portuguese nobility, see hidalgos and infanzones.

Swedish

[edit]In Sweden, there was no outright serfdom. Hence, the gentry was a class of well-off citizens that had grown from the wealthier or more powerful members of the peasantry. The two historically legally privileged classes in Sweden were the Swedish nobility (Adeln), a rather small group numerically, and the clergy, which were part of the so-called frälse (a classification defined by tax exemptions and representation in the diet).

At the head of the Swedish clergy stood the Archbishop of Uppsala since 1164. The clergy encompassed almost all the educated men of the day and furthermore was strengthened by considerable wealth, and thus it came naturally to play a significant political role. Until the Reformation, the clergy was the first estate but was relegated to the secular estate in the Protestant North Europe.

In the Middle Ages, celibacy in the Catholic Church had been a natural barrier to the formation of an hereditary priestly class. After compulsory celibacy was abolished in Sweden during the Reformation, the formation of a hereditary priestly class became possible, whereby wealth and clerical positions were frequently inheritable. Hence the bishops and the vicars, who formed the clerical upper class, would frequently have manors similar to those of other country gentry. Hence continued the medieval Church legacy of the intermingling between noble class and clerical upper class and the intermarriage as the distinctive element in several Nordic countries after the Reformation.

Surnames in Sweden can be traced to the 15th century, when they were first used by the Gentry (Frälse), i.e., priests and nobles. The names of these were usually in Swedish, Latin, German or Greek.

The adoption of Latin names was first used by the Catholic clergy in the 15th century. The given name was preceded by Herr (Sir), such as Herr Lars, Herr Olof, Herr Hans, followed by a Latinized form of patronymic names, e.g., Lars Petersson Latinized as Laurentius Petri. Starting from the time of the Reformation, the Latinized form of their birthplace (Laurentius Petri Gothus, from Östergötland) became a common naming practice for the clergy.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the surname was only rarely the original family name of the ennobled; usually, a more imposing new name was chosen. This was a period which produced a myriad of two-word Swedish-language family names for the nobility (very favored prefixes were Adler, "eagle"; Ehren – "ära", "honor"; Silfver, "silver"; and Gyllen, "golden"). The regular difference with Britain was that it became the new surname of the whole house, and the old surname was dropped altogether.

Ukraine

[edit]The Western Ukrainian Clergy of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church were a hereditary tight-knit social caste that dominated western Ukrainian society from the late eighteenth until the mid-20th centuries, following the reforms instituted by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor. Because, like their Eastern Orthodox brethren, Ukrainian Catholic priests could marry, they were able to establish "priestly dynasties", often associated with specific regions, for many generations. Numbering approximately 2,000–2,500 by the 19th century, priestly families tended to marry within their group, constituting a tight-knit hereditary caste.[16] In the absence of a significant native nobility and enjoying a virtual monopoly on education and wealth within western Ukrainian society, the clergy came to form that group's native aristocracy. The clergy adopted Austria's role for them as bringers of culture and education to the Ukrainian countryside. Most Ukrainian social and political movements in Austrian-controlled territory emerged or were highly influenced by the clergy themselves or by their children. This influence was so great that western Ukrainians were accused of wanting to create a theocracy in western Ukraine by their Polish rivals.[17] The central role played by the Ukrainian clergy or their children in western Ukrainian society would weaken somewhat at the end of the 19th century but would continue until the mid-20th century.

United States

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2021) |

The American gentry were rich landowning members of the American upper class in the colonial South.

The Colonial American use of gentry was not common. Historians use it to refer to rich landowners in the South before 1776. Typically large scale landowners rented out farms to white tenant farmers. North of Maryland, there were few large comparable rural estates, except in the Dutch domains in the Hudson Valley of New York.[18][19]

Great Britain

[edit]The British upper classes consist of two sometimes overlapping entities, the peerage and landed gentry. In the British peerage, only the senior family member (typically the eldest son) inherits a substantive title (duke, marquess, earl, viscount, baron); these are referred to as peers or lords. The rest of the nobility form part of the "landed gentry" (abbreviated "gentry"). The members of the gentry usually bear no titles but can be described as esquire or gentleman. Exceptions are the eldest sons of peers, who bear their fathers' inferior titles as "courtesy titles" (but for Parliamentary purposes count as commoners), Scottish barons (who bear the designation Baron of X after their name)[20] and baronets (a title corresponding to a hereditary knighthood). Scottish lairds do not have a title of nobility but may have a description of their lands in the form of a territorial designation that forms part of their name.[21]

The landed gentry is a traditional British social class consisting of gentlemen in the original sense; that is, those who owned land in the form of country estates to such an extent that they were not required to actively work, except in an administrative capacity on their own lands. The estates were often (but not always) made up of tenanted farms, in which case the gentleman could live entirely off rent income. Gentlemen, ranking below esquires and above yeomen, form the lowest rank of British nobility. It is the lowest rank to which the descendants of a Knight, Baronet or Peer can sink. Strictly speaking, anybody with officially matriculated English or Scottish arms is a gentleman and thus noble.

The term landed gentry, although originally used to mean nobility, came to be used for the lesser nobility in England around 1540. Once identical, these terms eventually became complementary. The term gentry by itself, as commonly used by historians, according to Peter Coss, is a construct applied loosely to rather different societies. Any particular model may not fit a specific society, yet a single definition nevertheless remains desirable.[22][23] Titles, while often considered central to the upper class, are not strictly so. Both Captain Mark Phillips and Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence, the respective first and second husbands of Anne, Princess Royal, lacked any rank of peerage at the time of their marriage to Princess Anne. However, the backgrounds of both men were considered to be essentially patrician, and they were thus deemed[by whom?] suitable husbands for a princess.

Esquire (abbreviated Esq.) is a term derived from the Old French word "escuier" (which also gave equerry) and is in the United Kingdom the second-lowest designation for a nobleman, referring only to males, and used to denote a high but indeterminate social status. The most common occurrence of term Esquire today is the conferral as the suffix Esq. in order to pay an informal compliment to a male recipient by way of implying gentle birth. In the post-medieval world, the title of esquire came to apply to all men of the higher landed gentry; an esquire ranked socially above a gentleman but below a knight. In the modern world, where all men are assumed to be gentlemen, the term has often been extended (albeit only in very formal writing) to all men without any higher title. It is used post-nominally, usually in abbreviated form (for example, "Thomas Smith, Esq.").

A knight could refer to either a medieval tenant who gave military service as a mounted man-at-arms to a feudal landholder, or a medieval gentleman-soldier, usually high-born, raised by a sovereign to privileged military status after training as a page and squire (for a contemporary reference, see British honours system). In formal protocol, Sir is the correct styling for a knight or for a baronet, used with (one of) the knight's given name(s) or full name, but not with the surname alone. The equivalent for a woman who holds the title in her own right is Dame; for such women, the title Dame is used as Sir for a man, never before the surname on its own. This usage was devised[by whom?] in 1917, derived from the practice, up to the 17th century (and still also in legal proceedings), for the wife of a knight. The wife of a knight or baronet is now styled "Lady [husband's surname]".

Historiography

[edit]The "Storm over the gentry" was a major historiographical debate among scholars that took place in the 1940s and 1950s regarding the role of the gentry in causing the English Civil War of the 17th century.[24] R. H. Tawney had suggested in 1941 that there was a major economic crisis for the nobility in the 16th and 17th centuries, and that the rapidly rising gentry class was demanding a share of power. When the aristocracy resisted, Tawney argued, the gentry launched the civil war.[25] After heated debate, historians generally concluded that the role of the gentry was not especially important.[26]

Irish

[edit]

The Irish gentry, often referred to as the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy, emerged as a dominant landowning class during British rule in Ireland. Comprising Protestant elites, they held significant political and social influence while overseeing vast estates. The Irish gentry also played a key role in shaping cultural and literary traditions, as seen with families like the Fitzgeralds and Butlers. However, their prominence waned after Irish independence and land reforms.

East Asia

[edit]China

[edit]The 'four divisions of society' refers to the model of society in ancient China and was a meritocratic social class system in China and other subsequently influenced Confucian societies. The four castes—gentry, farmers, artisans and merchants—are combined to form the term Shìnónggōngshāng (士農工商).

Gentry (士) means different things in different countries. In China, Korea, and Vietnam, this meant that the Confucian scholar gentry that would – for the most part – make up most of the bureaucracy. This caste would comprise both the more-or-less hereditary aristocracy as well as the meritocratic scholars that rise through the rank by public service and, later, by imperial exams. Some sources, such as Xunzi, list farmers before the gentry, based on the Confucian view that they directly contributed to the welfare of the state. In China, the farmer lifestyle is also closely linked with the ideals of Confucian gentlemen.

In Japan, this caste essentially equates to the samurai class.

Hierarchical structure of Feudal Japan

[edit]

There were two leading classes, i.e. the gentry, in the time of feudal Japan: the daimyō and the samurai. The Confucian ideals in the Japanese culture emphasised the importance of productive members of society, so farmers and fishermen were considered of a higher status than merchants.

In the Edo period, with the creation of the Domains (han) under the rule of Tokugawa Ieyasu, all land was confiscated and reissued as fiefdoms to the daimyōs.

The small lords, the samurai (武士, bushi), were ordered either to give up their swords and rights and remain on their lands as peasants or to move to the castle cities to become paid retainers of the daimyōs. Only a few samurai were allowed to remain in the countryside; the landed samurai (郷士, gōshi). Some 5 per cent of the population were samurai. Only the samurai could have proper surnames, something that after the Meiji Restoration became compulsory to all inhabitants (see Japanese name).

Emperor Meiji abolished the samurai's right to be the only armed force in favor of a more modern, Western-style, conscripted army in 1873. Samurai became Shizoku (士族), but the right to wear a katana in public was eventually abolished along with the right to execute commoners who paid them disrespect.

In defining how a modern Japan should be, members of the Meiji government decided to follow in the footsteps of the United Kingdom and Germany, basing the country on the concept of noblesse oblige. Samurai were not to be a political force under the new order. The difference between the Japanese and European feudal systems was that European feudalism was grounded in Roman legal structure while Japan feudalism had Chinese Confucian morality as its basis.[27]

Korea

[edit]Korean monarchy and the native ruling upper class existed in Korea until the end of the Japanese occupation. The system concerning the nobility is roughly the same as that of the Chinese nobility.

As the monastical orders did during Europe's Dark Ages, the Buddhist monks became the purveyors and guardians of Korea's literary traditions while documenting Korea's written history and legacies from the Silla period to the end of the Goryeo dynasty. Korean Buddhist monks also developed and used the first movable metal type printing presses in history—some 500 years before Johannes Gutenberg—to print ancient Buddhist texts. Buddhist monks also engaged in record keeping, food storage and distribution, as well as the ability to exercise power by influencing the Goryeo royal court.

Ottoman Middle East

[edit]

In the Ottoman Middle East, the gentry consisted of notables, or a'yan.[28] The a'yan consisted of two groups: urban and rural gentries. Urban elites were traditionally made of city-dwelling merchants (tujjar),[29] clerics ('ulema), ashraf, military officers, and governmental functionaries.[30][31][32] The rural notability's ranks included rural sheikhs and village or clan mukhtars. Most notables originated in, and belonged to, the fellahin (peasantry) class, forming a lower-echelon land-owning gentry in the Empire's post-Tanzimat countryside and emergent towns.[33] In Palestine, rural notables form the majority of Palestinian elites, although certainly not the richest.[34] Rural notables took advantage of changing legal, administrative and political conditions, and global economic realities, to achieve ascendancy using households, marriage alliances and networks of patronage.[34] Over all, they played a leading role in the development of modern Palestine and other countries well into the late 20th century.[35]

Values and traditions

[edit]Military and clerical

[edit]

Historically, the nobles in Europe became soldiers; the aristocracy in Europe can trace their origins to military leaders from the migration period and the Middle Ages. For many years, the British Army, together with the Church, was seen as the ideal career for the younger sons of the aristocracy. Although now much diminished, the practice has not totally disappeared. Such practices are not unique to the British either geographically or historically. As a very practical form of displaying patriotism, it has been at times fashionable for "gentlemen" to participate in the military.

The fundamental idea of gentry had come to be that of the essential superiority of the fighting man, usually maintained in the granting of arms.[36] At the last, the wearing of a sword on all occasions was the outward and visible sign of a "gentleman"; the custom survives in the sword worn with "court dress". A suggestion that a gentleman must have a coat of arms was vigorously advanced by certain 19th- and 20th-century heraldists, notably Arthur Charles Fox-Davies in England and Thomas Innes of Learney in Scotland. The significance of a right to a coat of arms was that it was definitive proof of the status of gentleman, but it recognised rather than conferred such a status, and the status could be and frequently was accepted without a right to a coat of arms.

Chivalry

[edit]

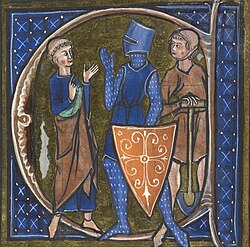

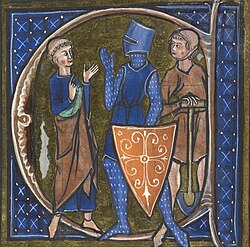

Chivalry[b] is a term related to the medieval institution of knighthood. It is usually associated with ideals of knightly virtues, honour and courtly love.

Christianity had a modifying influence on the virtues of chivalry, with limits placed on knights to protect and honour the weaker members of society and maintain peace. The church became more tolerant of war in the defence of faith, espousing theories of the just war. In the 11th century, the concept of a "knight of Christ" (miles Christi) gained currency in France, Spain and Italy.[37] These concepts of "religious chivalry" were further elaborated in the era of the Crusades.[37]

In the later Middle Ages, wealthy merchants strove to adopt chivalric attitudes.[37] This was a democratisation of chivalry, leading to a new genre called the courtesy book, which were guides to the behaviour of "gentlemen".[37]

When examining medieval literature, chivalry can be classified into three basic but overlapping areas:

- Duties to countrymen and fellow Christians

- Duties to God

- Duties to women

These three areas obviously overlap quite frequently in chivalry and are often indistinguishable. Another classification of chivalry divides it into warrior, religious and courtly love strands. One particular similarity between all three of these categories is honour. Honour is the foundational and guiding principle of chivalry. Thus, for the knight, honour would be one of the guides of action.

Gentleman

[edit]

The term gentleman (from Latin gentilis, belonging to a race or gens, and "man", cognate with the French word gentilhomme, the Spanish gentilhombre and the Italian gentil uomo or gentiluomo), in its original and strict signification, denoted a man of good family, analogous to the Latin generosus (its invariable translation in English-Latin documents). In this sense the word equates with the French gentilhomme ("nobleman"), which was in Great Britain long confined to the peerage. The term gentry (from the Old French genterise for gentelise) has much of the social-class significance of the French noblesse or of the German Adel, but without the strict technical requirements of those traditions (such as quarters of nobility). To a degree, gentleman signified a man with an income derived from landed property, a legacy or some other source and was thus independently wealthy and did not need to work.

Confucianism

[edit]The Far East also held similar ideas to the West of what a gentleman is, which are based on Confucian principles. The term Jūnzǐ (君子) is a term crucial to classical Confucianism. Literally meaning "son of a ruler", "prince" or "noble", the ideal of a "gentleman", "proper man", "exemplary person", or "perfect man" is that for which Confucianism exhorts all people to strive. A succinct description of the "perfect man" is one who "combine[s] the qualities of saint, scholar, and gentleman" (CE). A hereditary elitism was bound up with the concept, and gentlemen were expected to act as moral guides to the rest of society. They were to:

- cultivate themselves morally;

- participate in the correct performance of ritual;

- show filial piety and loyalty where these are due; and

- cultivate humaneness.

The opposite of the Jūnzǐ was the Xiǎorén (小人), literally "small person" or "petty person". Like English "small", the word in this context in Chinese can mean petty in mind and heart, narrowly self-interested, greedy, superficial, and materialistic.

Noblesse oblige

[edit]The idea of noblesse oblige, "nobility obliges", among gentry is, as the Oxford English Dictionary expresses, that the term "suggests noble ancestry constrains to honorable behaviour; privilege entails to responsibility". Being a noble meant that one had responsibilities to lead, manage and so on. One was not to simply spend one's time in idle pursuits.

Heraldry

[edit]

A coat of arms is a heraldic device dating to the 12th century in Europe. It was originally a cloth tunic worn over or in place of armour to establish identity in battle.[38] The coat of arms is drawn with heraldic rules for a person, family or organisation. Family coats of arms were originally derived from personal ones, which then became extended in time to the whole family. In Scotland, family coats of arms are still personal ones and are mainly used by the head of the family. In heraldry, a person entitled to a coat of arms is an armiger, and their family would be armigerous.[citation needed]

Ecclesiastical heraldry

[edit]Ecclesiastical heraldry is the tradition of heraldry developed by Christian clergy. Initially used to mark documents, ecclesiastical heraldry evolved as a system for identifying people and dioceses. It is most formalised within the Catholic Church, where most bishops, including the pope, have a personal coat of arms. Clergy in Anglican, Lutheran, Eastern Catholic and Orthodox churches follow similar customs.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Following the admired example of the Roman patrician, the Venetian patrician reverted, especially in the Renaissance, to a life more focused on his rural estate.

- ^ Etymology: English from 1292, loans from French chevalerie "knighthood", from chevalier "knight" from Medieval Latin caballarius "horseman"; cavalry is from the Middle French form of the same word.

References

[edit]- ^ "Gentry". THE GENTRY | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary. Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Cambridge. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2021-12-14.

- ^ "Gentry". English Dictionary. Oxford.[dead link]

- ^ "Patrician". Patrician - Definitions available for patrician from Cambridge Dictionary Online: Free English Dictionary and Thesaurus. Dictionary. Cambridge. Archived from the original on 2010-12-05. Retrieved 2010-11-05.

- ^ "The Origins of the English Gentry". Reviews in History. Archived from the original on 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2019-10-07.

- ^ "The Origins of the English Gentry Peter Coss" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-03-09.

- ^ Leiren, Terje I. (1999). "From Pagan to Christian: The Story in the 12th-Century Tapestry of the Skog Church". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 2004-10-23.

- ^ Mallory, J.P. In search of the Indo-Europeans Thames & Hudson (1991) p. 131

- ^ Boyd, William Kenneth (1905). The Ecclesiastical Edicts of the Theodosian Code. Columbia University Press.

- ^ a b Durant, Will (2005). Story of Philosophy. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-69500-2. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Celibacy as Political Resistance". First Things. January 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Mosca, Gaetano (1939). The Ruling Class. Translated by Hannah D Kahn. McGraw Hill. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "French Absolutism". SUNY Suffolk. Archived from the original on 2010-01-24. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку, губерниям и областям. Demoscope (in Russian). No. 469–470. 6–19 June 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29..

- ^ Harmat, Árpád Péter (12 February 2015). "Magyarország társadalma a dualizmus korában" (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Ross, M. (1835). "A Descriptive View of Poland: Character, Manners, and Customs of the Poles". A History of Poland from its Foundation as a State to the Present Time. Newcastle upon Tyne: Pattison and Ross. p. 51.

At least 60,000 families belong to this class [nobility], of which, however, only about 100 are wealthy; all the rest are poor.

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (1988). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 214–19..

- ^ Himka, John Paul (1999). Religion and Nationality in Western Ukraine. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 10..

- ^ See François-Joseph Ruggiu, "Extraction, wealth and industry: The ideas of noblesse and of gentility in the English and French Atlantics (17th–18th centuries)." History of European Ideas 34.4 (2008): 444-455 online[dead link]

- ^ Arthur M. Schlesinger, “The Aristocracy in Colonial America.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 74, 1962, pp. 3–21. online Archived 2021-11-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Court of the Lord Lyon". Archived from the original on 2017-10-09. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ^ "Chief, Chieftain or Laird". Forms of Address. Debrett's. Archived from the original on 2010-08-01. Retrieved 2010-07-18.

- ^ Hicks, Michael. "The Origins of the English Gentry" (review). UK. Archived from the original on 2018-06-27. Retrieved 2010-03-09..

- ^ Coss, Peter (13 October 2005). The Origins of the English Gentry (PDF). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52102100-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2010..

- ^ Fritze, Ronald H.; Robison, William B. (1996). Historical Dictionary of Stuart England, 1603-1689. Greenwood. pp. 205–7. ISBN 9780313283918.

- ^ R. H. Tawney, "The Rise of the Gentry, 1558-1640," Economic History Review (1941) 11#1 pp. 1–38 JSTOR 2590708

- ^ J.H. Hexter, 'Storm over the Gentry', in Hexter, Reappraisals in History (1961) pp. 117–62

- ^ Snyder, MR (October 1994). "Japanese vs. European Feudalism". Alberta Vocational College. Archived from the original on 2008-12-10. Retrieved 2010-03-09..

- ^ Batatu, Hanna (2012-09-17), Syria's Peasantry, the Descendants of Its Lesser Rural Notables, and Their Politics, Princeton University Press, doi:10.1515/9781400845842, ISBN 978-1-4008-4584-2, retrieved 2024-05-03

- ^ Gilbar, Gad (2022-10-31). Trade and Enterprise: The Muslim Tujjar in the Ottoman Empire and Qajar Iran, 1860-1914. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003177425. ISBN 978-1-003-17742-5.

- ^ Gelvin, James L. (2006). "The "Politics of Notables" Forty Years After". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 40 (1): 19–29. doi:10.1017/S002631840004935X. ISSN 0026-3184. JSTOR 23062629.

- ^ Cleveland, William L. (1989). Muslih, Muhammad Y. (ed.). "Politics of the Notables". Journal of Palestine Studies. 18 (3): 142–144. doi:10.2307/2537348. ISSN 0377-919X. JSTOR 2537348.

- ^ Toledano, Ehud R. "Ehud R. Toledano, "The Emergence of Ottoman-Local Elites (1700-1800): A Framework for Research," in I. Pappé and M. Ma'oz (eds.), Middle Eastern Politics and Ideas: A History from within, London and New York: Tauris Academic Studies, 1997, 145-162".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Landed Property and Elite Conflict in Ottoman Tulkarm". Institute for Palestine Studies. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ a b Marom, Roy (April 2024). "The Palestinian Rural Notables' Class in Ascendency: The Hannun Family of Tulkarm (Palestine)". Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. 23 (1): 77–108. doi:10.3366/hlps.2024.0327. ISSN 2054-1988 – via Academia.

- ^ "The Dynamics of Palestinian Elite Formation". Institute for Palestine Studies. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Selden, John (1614). Titles of Honour. p. 707.

- ^ a b c d Sweeney, James Ross (1983). "Chivalry". The Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Vol. III..

- ^ "Coat of arms". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.). Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 2022-06-21..

Further reading

[edit]Great Britain

[edit]- Acheson, Eric. A gentry community: Leicestershire in the fifteenth century, c. 1422–c. 1485 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

- Butler, Joan. Landed Gentry (1954)

- Coss, Peter R. The origins of the English gentry (2005) online

- Heal, Felicity. The gentry in England and Wales, 1500–1700 (1994) online.

- Mingay, Gordon E. The Gentry: The Rise and Fall of a Ruling Class (1976) online

- O'Hart, John. The Irish And Anglo-Irish Landed Gentry, When Cromwell Came to Ireland: or, a Supplement to Irish Pedigrees (2 vols) (reprinted 2007)

- Sayer, M. J. English Nobility: The Gentry, the Heralds and the Continental Context (Norwich, 1979)

- Wallis, Patrick, and Cliff Webb. "The education and training of gentry sons in early modern England." Social History 36.1 (2011): 36–53. online

Europe

[edit]- Eatwell, Roger, ed. European political cultures (Routledge, 2002).

- Jones, Michael ed. Gentry and Lesser Nobility in Late Medieval Europe (1986) online.

- Lieven, Dominic C.B. The aristocracy in Europe, 1815–1914 (Macmillan, 1992).

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. The modern world-system I: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. Vol. 1 (Univ of California Press, 2011).

- Wasson, Ellis. Aristocracy and the modern world (Macmillan International Higher Education, 2006), for 19th and 20th centuries

Historiography

[edit]- Hexter, Jack H. Reappraisals in history: New views on history and society in early modern Europe (1961), emphasis on England.

- MacDonald, William W. "English Historians Repeating Themselves: The Refining of the Whig Interpretation of the English Revolution and Civil War." Journal of Thought (1972): 166–175. online

- Tawney, R. H. "The rise of the gentry, 1558–1640." Economic History Review 11.1 (1941): 1–38. online; launched a historiographical debate

- Tawney, R. H. "The rise of the gentry: a postscript." Economic History Review 7.1 (1954): 91–97. online

China

[edit]- Bastid-Bruguiere, Marianne. "Currents of social change." The Cambridge History of China 11.2 1800–1911 (1980): pp. 536–571.

- Brook, Timothy. Praying for power: Buddhism and the formation of gentry society in late-Ming China (Brill, 2020).

- Chang, Chung-li. The Chinese gentry: studies on their role in nineteenth-century Chinese society (1955) online

- Chuzo, Ichiko; "The role of the gentry: an hypothesis." in China in Revolution: The First Phase, 1900–1913 ed. by Mary C. Wright (1968) pp: 297–317.

- Miller, Harry. State versus Gentry in Late Ming Dynasty China, 1572–1644 (Springer, 2008).

External links

[edit]Gentry

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Etymology and Core Attributes

The term gentry entered Middle English around 1300 from Old French genterie or gentilise, denoting "nobility of birth," "aristocratic customs," or "noble character traits such as honor and gentility." [9] This Old French form derived from gent ("well-born" or "of gentle birth"), ultimately tracing to Latin gentilis ("of the same clan" or "noble by birth"), emphasizing hereditary status tied to lineage rather than mere wealth or achievement. [10] By the 14th century, the English usage had solidified to describe a collective social stratum distinguished by refined manners and non-manual livelihoods, distinct from both titled aristocracy and laboring classes. [9] Historically, the gentry constituted a propertied class of landowners who ranked below the peerage but above yeomen farmers and merchants, comprising roughly 1-2% of England's population by the late medieval period and relying on rental incomes from estates rather than direct cultivation. [6] Core attributes included gentle birth—often evidenced by armigerous status like knighthoods or esquires—formal education in classics and law, and active participation in county governance, such as serving as sheriffs, justices of the peace, or militia captains to uphold order and royal interests. [11] Unlike nobility, gentry lacked hereditary titles or parliamentary summons but cultivated influence through intermarriage, patronage networks, and cultural refinement, including patronage of arts and literature, which reinforced their role as local elites mediating between crown and commons. [12] This stratum's cohesion stemmed from shared values of honor, piety, and martial readiness, though economic pressures like primogeniture often constrained younger sons to professions such as clergy or law. [8]Distinction from Nobility, Yeomanry, and Merchants

The gentry occupied a position in the social hierarchy below the nobility, distinguished primarily by the absence of hereditary titles conferring peerage status, such as those held by barons, earls, or dukes, which granted privileges like seats in the House of Lords and national political influence. Nobles typically commanded vast estates derived from feudal grants or royal favor, often spanning thousands of acres with extensive manorial rights, whereas gentry families owned smaller but substantial freehold lands, sufficient for rental income that obviated manual labor, yet without the legal immunities or summons to Parliament enjoyed by peers. This demarcation solidified in England by the late medieval period, with the gentry emerging as untitled "lesser nobility" focused on local justice and county administration, as evidenced in 16th-century records where gentry justices of the peace outnumbered noble counterparts in shire governance.[13] In contrast to the yeomanry, the gentry held larger estates worked by tenants and laborers, enabling a lifestyle of leisure, education, and public service rather than direct agricultural toil; yeomen, while prosperous freeholders owning 30 to 100 acres, personally cultivated their lands and ranked as a rural middle stratum between peasantry and gentry. Yeomen's status derived from self-sufficiency and military service, such as archery obligations under Tudor statutes like the 1537 Militia Act, but lacked the gentry's heraldic gentility or eligibility for knighthood without royal elevation. By the Elizabethan era (1558–1603), gentry wealth averaged £200–£500 annually from rents, far exceeding yeomen's £20–£50 from mixed farming and trades, underscoring the gentry's supervisory role over manors versus yeomen's hands-on husbandry.[13][14] Merchants differed from the gentry in their urban commercial foundations, deriving wealth from trade guilds, overseas ventures, and liquid capital rather than fixed agrarian assets, often amassing fortunes in ports like London or Bristol without the landed pedigree central to gentry identity. While successful merchants, such as those in the Merchant Adventurers' Company, could purchase estates to assimilate into the gentry—evident in 17th-century land transfers where trade profits funded 20–30% of new gentry holdings—the gentry's prestige hinged on hereditary rural dominion and county networks, viewing mercantile origins as inferior due to associations with manual exchange over noble birth. This distinction persisted causally from feudal land tenure laws favoring inherited estates over mobile commerce, with gentry resisting full integration of "new men" until ennoblement or generational dilution of trade ties.[15][13]Historical Origins and Development

Feudal Foundations in Medieval Europe

The gentry in medieval Europe emerged from the feudal system's structure of land tenure and vassalage, particularly among the lesser knights and landholders who provided military service in exchange for fiefs. Under feudalism, which solidified after the Carolingian era around the 9th-10th centuries, lords granted smaller estates to sub-vassals capable of equipping themselves as mounted warriors, forming the basis of a class distinct from high nobility yet elevated above free peasants.[16] These knights, often of non-noble origin initially, accumulated heritable landholdings that supported their status, with obligations including forty days of annual service to overlords.[17] In England, following the Norman Conquest of 1066, the gentry's roots trace to the integration of Anglo-Saxon thegns and Norman knights into a hierarchical system where approximately 5,000 knight's fees were recorded in the Cartae Baronum of 1166, delineating service obligations. By the 13th century, this class began differentiating through collective identity tied to knighthood, armorial bearings, and local administrative roles, evolving beyond pure military function amid declining feudal levies.[18] Historians like Peter Coss identify four defining traits: a graded status hierarchy, public office-holding in shires, collective authority in county governance, and a shared ideology emphasizing gentility over mere chivalry.[19] On the Continent, parallels existed in the French chevalerie and German ministeriales, where unfree knights or minor vassals managed manors and enforced justice, laying groundwork for gentry-like strata by the 14th century as commutation of services for money rents increased economic independence.[20] This shift, accelerated by the Black Death in 1348-1350 which disrupted labor and inflated land values, empowered gentry families to consolidate holdings and participate in representative assemblies, such as the English Parliament where knights of the shire represented their class from 1295 onward.[18] Thus, feudal military foundations transitioned into socio-political influence, distinguishing gentry as intermediaries between crown and commons.Expansion and Adaptation in the Early Modern Era

In England, the gentry class expanded significantly during the 16th century through the acquisition of former monastic lands following the Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1541, when King Henry VIII seized assets from over 800 religious houses, redistributing approximately one-quarter of England's cultivated land to secular owners, many of whom were established or aspiring gentry families.[21] This transfer not only increased the gentry's landholdings but also fostered agricultural innovation and higher yields in affected parishes, as monastic estates, previously unmarketed and burdened by customary tenures, entered a more dynamic land market.[22] Historians such as R. H. Tawney have argued that this period marked the "rise of the gentry," with their prosperity contrasting the financial strains on the nobility amid inflation and changing economic conditions from 1558 to 1640, though subsequent scholarship has nuanced the uniformity of this ascent.[23] The gentry adapted to the early modern economic shifts by embracing commercial agriculture and estate management practices, including the enclosure of common lands, which accelerated in the 16th and 17th centuries to boost productivity for wool and grain markets.[24] In local governance, gentry members increasingly served as Justices of the Peace, a role formalized under the Tudors, handling administrative, judicial, and fiscal duties that centralized royal authority while leveraging their landed status for influence in county affairs.[25] Educationally, sons of the gentry pursued grammar school instruction, followed by university attendance at Oxford or Cambridge and legal training at the Inns of Court, preparing them for bureaucratic and parliamentary roles rather than feudal military service, reflecting the decline of knightly obligations.[26] Across continental Europe, analogous groups adapted variably; in France, the noblesse de robe—administrative elites often from gentry-like backgrounds—rose through royal service, purchasing offices amid the erosion of feudal dues into money rents by the 16th century.[2] In Eastern Europe, such as Poland-Lithuania, the szlachta (gentry equivalent) expanded privileges through the 16th-century Golden Liberty, controlling vast estates as serfdom intensified, though this contrasted with Western trends toward absolutism where gentry supported monarchs against noble factions.[27] Overall, the early modern era saw the gentry transition from medieval vassals to key intermediaries in state-building, their adaptation driven by commercialization and centralization rather than hereditary feudal ties.Regional Manifestations

British Isles

In the British Isles, the gentry emerged as a distinct social stratum of lesser landowners who derived their status and income from hereditary estates, differentiating them from both the titled nobility above and the working yeomanry below. This class wielded significant influence in local affairs, particularly through administrative roles that reinforced central authority at the county level. While the term "gentry" is most closely associated with England, analogous groups existed in Ireland, often termed the Anglo-Irish gentry, shaped by colonial land policies and religious divisions. Their economic foundation rested on agricultural rents, with family estates serving as markers of gentility, including coats of arms and manorial rights.[28]English Gentry

The English gentry originated from medieval knights and substantial freeholders who held land by knight's service or socage tenure, evolving into a more defined class by the late fifteenth century. The Dissolution of the Monasteries between 1536 and 1540 accelerated their ascent, as crown sales of former ecclesiastical lands—comprising about one-quarter of England's cultivated acreage—enabled many gentry families to expand holdings and consolidate wealth.[21] This process contributed to a "rise of the gentry" in the sixteenth century, with family numbers growing; for instance, in Yorkshire, gentry households increased from 557 in 1558 to 679 by 1642.[28] By the seventeenth century, the gentry dominated rural society, comprising perhaps 1-2% of the population but controlling much of the land outside peerage estates.[29] Gentry men typically served as justices of the peace (JPs), a role formalized in the fourteenth century but expanded under the Tudors, where they formed the core of county commissions responsible for law enforcement, poor relief, militia organization, and quarter sessions.[30] This quasi-judicial authority, exercised without remuneration, underscored their stake in maintaining order on their estates while bridging royal policy and local custom. Many also sat in the House of Commons, representing county or borough seats, thus influencing national legislation on enclosure, poor laws, and taxation. Economically, they adapted to market agriculture, investing in improvements like drainage and crop rotation, though vulnerability to grain price fluctuations and inheritance disputes led to some family declines by the eighteenth century.[7]Irish Gentry

The Irish gentry, predominantly Anglo-Irish Protestants, arose from systematic land redistributions during England's conquest and colonization efforts, beginning with the Munster Plantation in the 1580s following the Desmond Rebellions and culminating in the Ulster Plantation authorized in 1609.[31] The Cromwellian conquest after the 1641 Irish Rebellion prompted further massive confiscations, with the Act for the Settlement of Ireland in 1652 declaring lands east of the River Shannon forfeit to the English Commonwealth, redistributing over 11 million acres to soldiers, adventurers, and loyalists while transplanting native owners to Connacht.[31] This created a gentry class of settler origin, holding estates under English tenure and often intermarrying with English families, forming the Protestant Ascendancy that dominated the Irish Parliament until the Act of Union in 1801. Unlike their English counterparts, many Irish gentry were absentee landlords, residing in England or Dublin while agents managed rack-rented tenancies, exacerbating tensions with Catholic tenants who comprised the majority of the population.[32] Their social role mirrored the English in local magistracy and grand juries, but was underpinned by Penal Laws from 1695 onward, which barred Catholics from landownership and office-holding, entrenching Protestant monopoly. The Great Famine of 1845–1852 and subsequent land agitation led to reforms via the Wyndham Land Act of 1903, enabling tenant purchase and eroding gentry estates, with many families selling out or emigrating by the early twentieth century.[33]English Gentry

The English gentry emerged as a distinct social class in the late medieval period, comprising landowners who held estates sufficient to generate income without personal labor, positioning them below the titled nobility yet above yeomen farmers. This group, often described as a form of lesser nobility, gained prominence from the 14th century as the number of greater barons diminished following parliamentary reforms and the Wars of the Roses, leaving the gentry to manage local affairs and feudal remnants.[34] By the 15th century, they constituted a key stratum in rural society, with estimates suggesting they owned significant portions of arable land and influenced county governance through roles like sheriffs and coroners.[20] In the Tudor era (1485–1603), the gentry's administrative role intensified under royal centralization, as monarchs like Henry VIII relied on them as justices of the peace (JPs) to enforce statutes, collect taxes, and maintain order at the local level, granting them quasi-judicial powers that solidified their authority over yeomen and laborers.[30] This period saw gentry education expand via grammar schools, universities such as Oxford and Cambridge, and the Inns of Court, fostering a class ethos centered on honor, virtue, and public service rather than mere martial prowess.[35] During the Stuart dynasties (1603–1714), they dominated the House of Commons, led county militias, and navigated religious upheavals, with many aligning as Cavaliers in the Civil War, though their landed base provided resilience against economic shifts.[36] The gentry's characteristics emphasized genteel conduct, heraldic entitlement, and estate management, distinguishing them from merchants through inherited status over commercial wealth, though intermarriage blurred lines by the 18th century. Personal wealth derived from rents, with typical holdings ranging from 1,000 to several thousand acres, enabling lifestyles of patronage, hunting, and literary pursuits as depicted in contemporary portraits.[2] Their influence peaked in the 18th century, shaping Whig politics and agricultural improvements, but declined in the 19th century amid the agricultural depression of 1873–1896, which halved land values, coupled with rising death duties introduced in 1894 that forced estate sales.[7] By 1881, approximately 4,200 families owned estates over 1,000 acres, but by the early 20th century, industrial taxation and urban migration reduced their numbers, with over half of gentry land transferred by 1914.[37]Irish Gentry

The Irish gentry consisted primarily of lesser landowners who derived income from estates worked by tenants, forming a social class intermediate between the nobility and yeoman farmers, with roots tracing to the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169–1171, when invaders such as the FitzGeralds and Butlers received grants of confiscated Gaelic lands from English monarchs.[38] These "Old English" families, initially Catholic, intermarried with native Irish elites and held sway in the Pale and eastern provinces until the Tudor plantations of the 16th century introduced Protestant settlers, particularly in Munster (1580s) and Ulster (1609 onward), diluting Catholic influence among the gentry.[39] By the Cromwellian confiscations of the 1650s, over 80% of Irish land had been redistributed to Protestant adventurers and soldiers, elevating a new Anglo-Irish Protestant gentry that dominated rural society through the 18th century, often residing on estates of 1,000 to 10,000 acres yielding rental incomes sufficient for genteel lifestyles without noble titles.[40] In the 18th century, the Irish gentry numbered around 5,000 families, managing estates through agents amid absentee landlordism by higher nobility, and playing key roles in local governance via grand juries and county militias, though Penal Laws from 1695 onward barred most Catholic gentry from land inheritance, political office, or Catholic worship, reducing their class to fragmented holdings and prompting conversions or emigration.[41] Burke's Landed Gentry of Ireland (1899 edition) documented over 1,200 such families, predominantly Protestant, whose wealth stemmed from agriculture, with barley and linen exports peaking in Ulster by the 1770s, yet vulnerability to subsistence crises like the 1740–1741 famine exposed tenant dependencies.[42] The Great Famine of 1845–1852 accelerated distress, as potato blight halved the population through death and emigration, forcing gentry sales of over 500 estates by 1850 to cover debts from uneconomic rents and poor relief costs.[43] The gentry's decline intensified during the Land War of 1879–1882, when tenant agitation against rack-rents led to boycotts and violence, culminating in Gladstone's Land Acts: the 1870 Act established courts for fair rent fixation, the 1881 Act introduced the "3 Fs" (fair rent, fixity of tenure, free sale), and the 1903 Wyndham Act enabled compulsory purchases, transferring 8 million acres to tenants by 1909 at state-subsidized annuities.[44] By the 1923 Land Act under the Irish Free State, remaining estates faced compulsory acquisition, ending the gentry's land monopoly; of Ireland's approximately 20 million acres in 1921, over 75% had passed to former tenants, rendering most gentry families landless or reliant on urban professions, with "Big Houses" like those in County Cork demolished or repurposed amid economic unviability and anti-landlord sentiment.[45] This redistribution, while empowering smallholders, fragmented agriculture and contributed to rural depopulation, as gentry capital for improvements evaporated.[46]Continental Europe

In continental Europe, the gentry concept appeared in varied forms, often as untitled or lower nobility with landownership privileges, distinct from higher titled aristocracy but sharing military and fiscal exemptions rooted in feudal obligations. Unlike the more rigidly stratified English gentry, continental equivalents frequently blurred into broader noble classes, with privileges like tax immunity tied to service rather than strict social demarcation. These groups emerged from medieval knightly orders, evolving through early modern absolutism and Enlightenment reforms, influencing regional power dynamics until the 19th-century upheavals.[47]Iberian Gentry

The Iberian Peninsula featured the hidalgo class in Spain as a primary gentry equivalent, denoting hereditary nobles of lower rank without titles such as duke or count, originating from medieval knights (infanzones) who proved noble lineage for privileges like tax exemptions and precedence in courts. By the 15th century, hidalgos numbered around 2-5% of the population in Castile, often living modestly on small estates while claiming exemption from personal taxes (pechos) and certain labors, a status formalized through cartas ejecutorias proving ancient bloodlines. In Portugal, analogous fidalgos held similar untitled noble status, supporting military duties under the crown. These groups bolstered Spain's imperial expansion, providing officers and administrators, though economic pressures from the 16th-century inflation eroded many holdings, leading to proletarianization by the 18th century.[48][49]Central and Eastern European Gentry

In Poland-Lithuania, the szlachta constituted a vast noble class often likened to gentry due to its landowning base and untitled majority, but legally all members were equal nobles with political rights, comprising up to 10% of the population by the 16th century and controlling the elective monarchy through the Golden Liberty. Emerging from 14th-century knightly consolidation, poorer szlachta (szlachta zagrodowa) resembled gentry in modest agrarian lifestyles, yet the class rejected gentry translations, emphasizing noble equality over hierarchical distinctions. In Hungary, the noble or gentile class paralleled this, with untitled landowners (lateral nobles) holding tax exemptions and seigniorial rights over peasants, peaking in influence during the 15th-century Jagiellonian era before Ottoman incursions fragmented estates. These eastern gentry-nobles wielded parliamentary power, resisting absolutism, but partitions and reforms in the 18th-19th centuries diminished their autonomy.[50]Baltic and Scandinavian Gentry

Scandinavian gentry aligned with the frälse estate in Sweden and Denmark-Norway, signifying tax-exempt landowners obligated to furnish equipped knights for royal service, formalized by Sweden's Ordinance of Alsnö in 1280, which granted fiscal privileges to families maintaining military readiness. By the 14th century, frälse included both high nobility and lesser gentry managing manors, comprising about 1-2% of the population, with Swedish noble families often bearing Latinized names reflecting clerical influences. In the Baltic regions under Swedish or German dominion, Baltic German landowners formed a gentry-like elite, inheriting crusader estates from the 13th century and dominating Livonian and Estonian manors until 1918, intermarrying locals while preserving German customs and serf-based agriculture. These groups supported crown policies in wars and administration but faced decline amid 19th-century emancipation and national awakenings.[51][52]Baltic and Scandinavian Gentry

The Baltic gentry primarily comprised Baltic Germans who established themselves as the dominant landowning class in the territories of present-day Estonia and Latvia following the 13th-century Northern Crusades. These settlers, initially knights and nobles from the Teutonic Order and related groups, consolidated political and economic control through the development of a manorial system, where they oversaw serf-based agriculture and local governance for nearly 700 years.[53] The class included both titled nobility (dukes, counts, barons) and untitled knights and landowners, who intermarried with local populations but preserved a distinct German ethnic identity and privileges, such as autonomy from direct royal oversight even under Swedish (17th century) and Russian (18th–19th centuries) suzerainty.[54] [53] Lutheranism was adopted by the landed gentry in the 16th century, albeit with initial reluctance, aligning them with Protestant reforms while reinforcing their estate-based authority over Baltic peasants.[53] In Scandinavia, the gentry equivalent manifested most distinctly in Sweden as the frälse, a class of tax-exempt landowners bound by feudal obligations to supply armed retainers—such as knights or troopers—to the king in exchange for immunity from royal taxes and corvée labor. This system originated in the medieval period as an extension of earlier Viking-age freeholder traditions, with the frälse distinguishing itself from the taxed peasantry (ofvälse) by the 13th–14th centuries through formalized privileges tied to military service.[52] Unlike in much of continental Europe, Sweden lacked institutionalized serfdom, enabling the frälse to emerge from wealthier freeholders and yeomen who accumulated estates via royal grants, with surnames appearing among them by the 15th century.[52] The class expanded during Sweden's 17th-century imperial era, when conquests in the Baltic and Germany enriched noble and gentry families, peaking their influence in the Riksdag estates before gradual equalization under absolutism and later reforms diminished hereditary exemptions by the 19th century.[51] In Denmark and Norway, analogous gentry structures developed through regional aristocracies that gained strength post-1350, with Danish nobles advancing land consolidation and advisory roles in royal councils amid the Kalmar Union (1397–1523), though untitled landowners remained integrated with higher nobility without Sweden's stark frälse delineation.[55] Baltic-Scandinavian interactions, particularly Sweden's control of Livonia and Estonia from 1629 to 1721, facilitated some cross-pollination, as Swedish frälse intermarried with Baltic German families, blending military and agrarian roles across the regions until nationalist upheavals in the 19th–20th centuries eroded gentry privileges.[53][51]Central and Eastern European Gentry

In Central and Eastern Europe, the gentry formed the lower nobility, distinguished by hereditary landownership, exemption from certain taxes, and participation in representative assemblies, often below a stratum of greater magnates. This class emerged from medieval warrior elites granted estates for military service, evolving into a politically assertive group by the late Middle Ages. Unlike Western European counterparts, CEE gentry frequently comprised a significant proportion of the population, influencing governance through diets or sejm-like bodies.[56] The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth exemplified this with its szlachta, a nobility estimated at 8-15% of the population, numbering around 700,000-1,000,000 individuals by the 18th century amid a total populace of 10-12 million. Originating in the Piast dynasty's knightly retinues from the 12th century, the szlachta secured privileges via statutes like the 1505 Nihil novi act, establishing "Golden Liberty" (Złota Wolność), which included tax exemptions, the right to bear arms, and the liberum veto allowing any member to block legislation. These rights, ostensibly exchanged for military obligations to the crown, empowered the szlachta in electing kings and dominating the Sejm, though they contributed to state paralysis by the 18th century.[57][58] In Hungary, the nemesség or gentry paralleled this structure, tracing to the Árpád-era conquest nobility from the 11th century, with privileges formalized by the 1222 Golden Bull of Andrew II, guaranteeing land rights and assembly participation. By the 15th century, nobility encompassed a broad segment, potentially up to 5% of society, sustaining influence in county diets and national assemblies despite Habsburg overlordship after 1526. The gentry's conservative outlook shaped parliamentary traditions, prioritizing local autonomy and resisting centralization.[56][59] Bohemian and Moravian gentry, known as vladykové or knights, gained prominence during the 14th-15th centuries, holding smaller estates and wielding influence in land diets, particularly amid the Hussite Wars (1419-1434) where lower nobles supported reformist causes against higher clergy and crown. Their role involved local administration and military levies, but Habsburg absolutism from the 16th century curtailed privileges, integrating them into a more stratified nobility.[60] Across the region, 18th-19th century partitions, enlightened reforms, and peasant emancipations eroded gentry dominance; in Poland, privileges ended with the 1791 Constitution's failures and partitions, while Hungarian gentry faced equalization post-1848 and land reforms in 1945. This decline reflected broader shifts from feudal estates to modern economies, diminishing the gentry's intermediary role between peasants and magnates.[61][56]Iberian Gentry

In Spain, the equivalent of the gentry was the hidalgo class, comprising hereditary minor nobility without formal titles or grand estates, positioned below higher peers but above commoners. This status conferred key privileges, including exemptions from royal and municipal taxes, civil and criminal immunities, priority in municipal offices, and exemptions from quartering soldiers.[49] Recognition often required pleitos de hidalguía lawsuits adjudicated by royal chanceries, culminating in cartas ejecutorias—royal confirmations of noble lineage, loyalty, and purity of blood—which peaked in the 16th century with around 200 cases annually in the 1550s and over 42,000 preserved in Valladolid's archives.[49] By 1541, hidalgos accounted for an estimated 5-10% of Castile's population, exceeding 100,000 families, many of whom were economically modest or landless yet upheld social prestige through military service and local influence.[62] Originating from frontier warriors during the Reconquista (8th–15th centuries), hidalgos sustained the martial ethos into the Spanish Empire, forming the core of armies that secured dominance in Europe and the Americas while embedding Reconquista ideals into imperial ideology.[63] In Portugal, the fidalgo similarly represented untitled or lesser nobility, embodying a warrior-aristocratic ethos tied to royal service and expansion. Fidalgos held privileges akin to hidalgos, such as legal protections and precedence in governance, and were integral to the kingdom's maritime ventures from the 15th century onward. They commanded fleets and expeditions during the Age of Discoveries, exemplified by figures like Diogo Lopes de Sequeira (c. 1465–1530), who led voyages to India following Vasco da Gama's 1497 route, and Pedro Álvares Cabral, a fidalgo overseeing the 1500 Brazil discovery fleet.[64] [65] As armored elites, fidalgos directed conquests in Africa, Asia, and Brazil, prioritizing crusading zeal and trade control—such as issuing cartazes for safe passage—over mere settlement, thereby sustaining Portugal's far-flung empire until the 19th century.[66] This class's proliferation mirrored Spain's, with many fidalgos relying on imperial opportunities rather than domestic landholdings, though their status eroded post-monarchy in 1910.[67] Across Iberia, these groups blurred lines between gentry and low nobility due to Reconquista legacies and imperial demands, fostering a culture of honor-bound service over commercial wealth, distinct from northern Europe's more agrarian gentry. Economic pressures often reduced them to penury, prompting migration to colonies where they replicated patronage networks in administration and encomiendas.[63] [68]Americas

In the Americas, the gentry class emerged primarily within the British North American colonies, adapting English traditions to the plantation economies of the Southern seaboard. This non-hereditary elite of wealthy landowners, reliant on enslaved labor for tobacco and other cash crops, wielded disproportionate economic, social, and political influence, particularly in Virginia and North Carolina, from the mid-17th century onward. Unlike European counterparts, American gentry lacked formal titles but emulated aristocratic lifestyles through land accumulation, education abroad, and local patronage networks.[69][70]Colonial American Gentry