Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

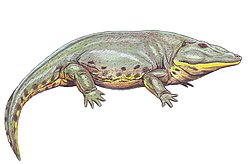

Eryops

View on Wikipedia

| Eryops | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Eryops megacephalus at the American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Tetrapoda |

| Order: | †Temnospondyli |

| Family: | †Eryopidae |

| Genus: | †Eryops Cope, 1877 |

| Species: | †E. megacephalus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Eryops megacephalus Cope, 1877

| |

Eryops (/ˈɛri.ɒps/; from Greek ἐρύειν, eryein, 'drawn-out' + ὤψ, ops, 'face', because most of its skull was in front of its eyes) is a genus of extinct, amphibious temnospondyls. It contains the type species Eryops megacephalus, the fossils of which are found mainly in early Permian deposits of the Texas Red Beds, and Eryops grandis from New Mexico. Fossils have also been found in late Carboniferous rocks from New Mexico and early Permian deposits of Oklahoma, Utah, the Pittsburgh tri-state region, and Prince Edward Island. Several complete skeletons of Eryops have been found in lower Permian rocks, but skull bones and teeth are its most common fossils.

Description

[edit]

Eryops averaged a little over 1.5–2.0 m (4 ft 11 in – 6 ft 7 in) long and could grow up to 3 m (9 ft 10 in),[1] making them among the largest land animals of their time. Adults have been estimated to weigh between 102 and 222 kg (225 and 489 lb).[2] The skull was large and relatively broad compared to coeval temnospondyls; the skull reached lengths of around 45 cm (18 in).[3][4]

The postcranial skeleton of Eryops is among the most completely known of all temnospondyls.[5][6][7][8][9] The configuration of the postcrania is similar to that of other temnospondyls, but the relative degree of ossification and overall size of the animal produce some of the sturdiest and most robust postcrania among Paleozoic temnospondyls.[10]

The texture of Eryops skin was revealed by a fossilized "mummy" described in 1941. This mummy specimen showed that the body in life was covered in a pattern of oval bumps.[11]

Discovery and species

[edit]

Eryops is currently thought to contain two presently valid species. The type species, E. megacephalus, refers to the "large-headed" aspect of the genus. Remains of E. megacephalus have been found in rocks dated to the early Permian period (Sakmarian age, about 295 million years ago) in the southwestern United States. Most of these specimens, including the type material, have little to no locality information other than that they are from the early Permian of Texas,[12] but more definitively placed specimens are recorded for much of the Cisuralian, including the Putnam, Admiral, Belle Plains, and Clyde Formations.[13][3][14][15][8] The second nominal species is Eryops grandis, which was described from the Cutler Formation of New Mexico and also known from Colorado.[16][12][17]

Various other valid temnospondyl taxa were previously placed in the genus. During the mid-20th century, some older fossils were classified as a second species of Eryops, E. avinoffi. This species, known from Carboniferous period fossil found in Pennsylvania, had originally been classified in the genus Glaukerpeton.[18] Beginning in the late 1950s,[19][20] some scientists concluded that Glaukerpeton was too similar to Eyrops to merit taxonomic distinction. However, revision of the material confirmed that it could be differentiated from Eryops based on various morphological features.[21] 'Eryops anatinus' and 'Eryops latus' are both junior synonyms of E. megacephalus. 'Eryops' ferricolus is now recognized as a dissorophid, Parioxys,[12][22] 'Eryops platypus' is a junior synonym of the amphibamid Platyrhinops lyelli,[23] and 'Eryops africanus' and 'Eryops oweni' are rhinesuchids.[24] 'Eryops reticulatus' is regarded as a nomen vanum,[16] though it is alternatively regarded as a junior synonym of E. grandis.[12]

Material only tentatively referred to E. megacephalus or only to the genus has been reported from Kansas,[25] New Mexico[16], Utah,[26][27] Oklahoma,[28][29][30] and Prince Edward Island.[31] The primary material of Eryops that has been reported from the Conemaugh Group in West Virginia[20] has also been reidentified as Glaukerpeton,[21] although unpublished specimens referred to Eryops sp. (and with acknowledgment of the validity of Glaukerpeton) have been listed from this region.[12]

Paleobiology

[edit]Eryops was one of the largest non-amniote tetrapods of the early Permian; among temnospondyls, it was rivaled in size only by edopoids, which were relatively rare.[32] The ecology of Eryops has been extensively debated and remains without consensus due to conflicting signals from different lines of evidence, such as external morphology,[8][4] biomechanical modeling,[33] and bone histology.[34][35][36][37] Eryops lived in lowland habitats in and around ponds, streams, and rivers, and the arrangement and shape of their teeth suggests that they probably ate mostly large fish and aquatic tetrapods.[1] The torso of Eryops was relatively stiff and the tail stout, which would have made them poor swimmers. While they probably fed on fish, adult Eryops must have spent most of their time on land.[1]

Like other large primitive temnospondyls, Eryops would have grown slowly and gradually from aquatic larvae, but they did not go through a major metamorphosis like many modern amphibians. While adults probably lived in ponds and rivers, perhaps venturing onto their banks, juvenile Eryops may have lived in swamps, which possibly offered more shelter from predators.[38][1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Schoch, Rainer R. (2009). "Evolution of life cycles in early amphibians". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 37 (1): 135–162. Bibcode:2009AREPS..37..135S. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.031208.100113.

- ^ Hart, L.J.; Campione, N.E.; McCurry, M.R. (2022). "On the estimation of body mass in temnospondyls: a case study using the large-bodied Eryops and Paracyclotosaurus". Palaeontology. 65 (6) e12629. doi:10.1111/pala.12629.

- ^ a b Sawin, Horace J. (1941). "The cranial anatomy of Eryops megacephalus". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 88 (5): 405–463.

- ^ a b Schoch, Rainer R. (2021-09-30). "The life cycle in late Paleozoic eryopid temnospondyls: developmental variation, plasticity and phylogeny". Fossil Record. 24 (2): 295–319. doi:10.5194/fr-24-295-2021. ISSN 2193-0066.

- ^ Cope, E. D. (1888). "Article VI. On the Shoulder Girdle and Extremities of Eryops". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 16 (2). The American Philosophical Society Press: 362–380. doi:10.70249/9798893985061-005.

- ^ Miner, Roy W. (1925). "The pectoral limb of Eryops and other primitive tetrapods". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 145: 145–312.

- ^ Moulton, James M. (1974). "A description of the vertebral column of Eryops, based on the notes and drawings of A.S. Romer". Breviora. 428: 1–44.

- ^ a b c Pawley, Kat; Warren, Anne (2006). "The appendicular skeleton of Eryops megacephalus Cope, 1877 (Temnospondyli: Eryopoidea) from the Lower Permian of North America". Journal of Paleontology. 80 (3): 561–580. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2006)80[561:TASOEM]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4095151. S2CID 56320401.

- ^ Dilkes, David (2014). "Carpus and tarsus of Temnospondyli". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 1: 51–87. doi:10.18435/B5MW2Q. ISSN 2292-1389.

- ^ Pawley, Kat (June 2007). "The postcranial skeleton of Temnospondyls (Tetrapoda: Temnospondyli)". Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 140 (1–2): 24–25. doi:10.5962/p.361587. ISSN 0035-9173.

- ^ Romer, A. S.; Witter, R. V. (1941). "The skin of the rachitomous amphibian Eryops". American Journal of Science. 239 (11): 822–824. Bibcode:1941AmJS..239..822R. doi:10.2475/ajs.239.11.822.

- ^ a b c d e Schoch, Rainer R.; Milner, Andrew R. (2014). Sues, Hans-Dieter (ed.). Temnospondyli I. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie / Begr. von Oskar Kuhn. Hrsg. von Peter Wellnhofer. [Fortges. von Hans-Dieter Sues]. Unter Mitarb. von R. M. Appleb ... = Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology. München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. ISBN 978-3-89937-170-3.

- ^ ROMER, A. S. (1935-11-30). "Early history of Texas redbeds vertebrates". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 46 (11): 1597–1657. doi:10.1130/gsab-46-1597. ISSN 0016-7606.

- ^ Sander, P.Martin (January 1987). "Taphonomy of the Lower Permian Geraldine Bonebed in Archer County, Texas". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 61: 221–236. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(87)90051-4. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Martin Sander, P. (January 1989). "Early permian depositional environments and pond bonebeds in central archer County, Texas". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 69: 1–21. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(89)90153-3. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b c Werneburg, R.; S.G. Lucas; J.W. Schneider; L.F. Rinehart (2010). "First Pennsylvanian Eryops (Temnospondyli) and its Permian record from New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; J.W. Schneider; J.A. Spielmann (eds.). Carboniferous-Permian transition in Canõn del Cobre, northern New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. Vol. 49. pp. 129–135.

- ^ Lewis, G.E.; Vaughn, P.P. (1965). "Early Permian vertebrates from the Culter Formation of the Placerville area, Colorado, with a section on footprints from the Cutler Formation". Professional Paper. doi:10.3133/pp503c. ISSN 2330-7102.

- ^ Romer, Alfred S. (1952). "Late Pennsylvanian and Early Permian vertebrates in the Pittsburgh-West Virginia region". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 33: 47–113. doi:10.5962/p.215221.

- ^ Vaughn, Peter Paul (1958). "On the Geologic Range of the Labyrinthodont Amphibian Eryops". Journal of Paleontology. 32 (5): 918–922. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1300709.

- ^ a b Murphy, James L. (1971). "Eryopsid Remains from the Conemaugh Group, Braxton County, West Virginia". Southeastern Geology. 13 (4): 265–273.

- ^ a b Werneburg, Ralf; Berman, David S (2012). "Revision of the aquatic eryopid temnospondyl Glaukerpeton avinoffi Romer, 1952, from the Upper Pennsylvanian of North America". Annals of Carnegie Museum. 81: 33–60. doi:10.2992/007.081.0103. S2CID 83566130.

- ^ Schoch, Rainer R.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (July 2022). "The dissorophoid temnospondyl Parioxys ferricolus from the early Permian (Cisuralian) of Texas". Journal of Paleontology. 96 (4): 950–960. doi:10.1017/jpa.2022.10. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Clack, J. A.; Milner, A. R. (September 2009). "Morphology and systematics of the Pennsylvanian amphibian Platyrhinops lyelli (Amphibia: Temnospondyli)". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 100 (3): 275–295. doi:10.1017/s1755691010009023. ISSN 1755-6910.

- ^ Marsicano, Claudia A.; Latimer, Elizabeth; Rubidge, Bruce; Smith, Roger M.H. (2017-05-29). "The Rhinesuchidae and early history of the Stereospondyli (Amphibia: Temnospondyli) at the end of the Palaeozoic". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlw032. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Aber, Susan W.; Peterson, Naomi; May, William J.; Johnston, Paul; Aber, James S. (September 2014). "First Report of Vertebrate Fossils in the Snyderville Shale (Oread Formation; Upper Pennsylvanian), Greenwood County, Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 117 (3 & 4): 193–202. doi:10.1660/062.117.0304. ISSN 0022-8443.

- ^ Vaughn, Peter Paul (1964). "Vertebrates from the Organ Rock Shale of the Cutler Group, Permian of Monument Valley and Vicinity, Utah and Arizona". Journal of Paleontology. 38 (3): 567–583. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1301529.

- ^ Huttenlocker, Adam K.; Henrici, Amy; John Nelson, W.; Elrick, Scott; Berman, David S; Schlotterbeck, Tyler; Sumida, Stuart S. (June 2018). "A multitaxic bonebed near the Carboniferous–Permian boundary (Halgaito Formation, Cutler Group) in Valley of the Gods, Utah, USA: Vertebrate paleontology and taphonomy". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 499: 72–92. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.03.017. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ Moodie, Roy L. (1911). "The temnospondylous amphibia and a new species of Eryops from the Permian of Oklahoma". The Kansas University Science Bulletin. 5 (13): 235–253.

- ^ Olson, Everett C. (1991-03-28). "An eryopid (Amphibia: Labyrinthodontia) from the Fort Sill fissures, Lower Permian, Oklahoma". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (1): 130–132. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011379. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ KISSEL, RICHARD A.; LEHMAN, THOMAS M. (May 2002). "Upper Pennsylvanian Tetrapods from the Ada Formation of Seminole County, Oklahoma". Journal of Paleontology. 76 (3): 529–545. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2002)076<0529:uptfta>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Langston, Wann J. (1963). "Fossil vertebrates and the Late Palaeozoic red beds of Prince Edward Island". National Museum of Canada Bulletin. 187: 1–36.

- ^ Romer, Alfred S.; Witter, Robert V. (November 1942). "Edops, a Primitive Rhachitomous Amphibian from the Texas Red Beds". The Journal of Geology. 50 (8): 925–960. doi:10.1086/625101. ISSN 0022-1376.

- ^ Herbst, Eva C; Manafzadeh, Armita R; Hutchinson, John R (2022-06-10). "Multi-Joint Analysis of Pose Viability Supports the Possibility of Salamander-Like Hindlimb Configurations in the Permian TetrapodEryops megacephalus". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 62 (2): 139–151. doi:10.1093/icb/icac083. ISSN 1540-7063. PMC 9405718. PMID 35687000.

- ^ SANCHEZ, S.; GERMAIN, D.; DE RICQLÈS, A.; ABOURACHID, A.; GOUSSARD, F.; TAFFOREAU, P. (2010-09-06). "Limb-bone histology of temnospondyls: implications for understanding the diversification of palaeoecologies and patterns of locomotion of Permo-Triassic tetrapods". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 23 (10): 2076–2090. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02081.x. ISSN 1010-061X. PMID 20840306.

- ^ Quémeneur, S.; de Buffrénil, V.; Laurin, M. (2013). "Microanatomy of the amniote femur and inference of lifestyle in limbed vertebrates". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 109 (3): 644–655. doi:10.1111/bij.12066.

- ^ Konietzko-Meier, Dorota; Danto, Marylène; Gądek, Kamil (2014-07-22). "The microstructural variability of the intercentra among temnospondyl amphibians". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 112 (4): 747–764. doi:10.1111/bij.12301. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ Konietzko-Meier, Dorota; Shelton, Christen D.; Martin Sander, P. (January 2016). "The discrepancy between morphological and microanatomical patterns of anamniotic stegocephalian postcrania from the Early Permian Briar Creek Bonebed (Texas)". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 15 (1–2): 103–114. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2015.06.005. ISSN 1631-0683.

- ^ Bakker, Robert T. (1982-07-02). "Juvenile-Adult Habitat Shift in Permian Fossil Reptiles and Amphibians". Science. 217 (4554): 53–55. doi:10.1126/science.217.4554.53. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17739981.