Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Relocation (computing)

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (July 2024) |

In software development, relocation is the process of assigning load addresses for position-dependent code and data of a program and adjusting the code and data to reflect the assigned addresses.[1][2]

A linker usually performs relocation in conjunction with symbol resolution, the process of searching files and libraries to replace symbolic references or names of libraries with actual usable addresses in memory before running a program.

Relocation is typically done by the linker at link time, but it can also be done at load time by a relocating loader, or at run time by the running program itself.

Segmentation

[edit]Object files are typically segmented into various memory segment or section types. Example segment types include code segment (.text), initialized data segment (.data), uninitialized data segment (.bss), or others as established by the programmer, such as common segments, or named static segments.

Relocation table

[edit]The relocation table is a list of addresses created by a compiler or assembler and stored in the object or executable file. Each entry in the table references an absolute address in the object code that must be changed when the loader relocates the program so that it will refer to the correct location. Entries in the relocation table are known as fixups and are designed to support relocation of the program as a complete unit. In some cases, each fixup in the table is itself relative to a base address of zero, so the fixups themselves must be changed as the loader moves through the table.[2]

In some architectures, a fixup that crosses certain boundaries (such as a segment boundary) or that is not aligned on a word boundary is illegal and flagged as an error by the linker.[3]

DOS and 16-bit Windows

[edit]Far pointers (32-bit pointers with segment:offset, used to address 20-bit 640 KB memory space available to DOS programs), which point to code or data within a DOS executable (EXE), do not have absolute segments, because the actual address of code or data depends on where the program is loaded in memory and this is not known until the program is loaded.

Instead, segments are relative values in the DOS EXE file. These segments need to be corrected, when the executable has been loaded into memory. The EXE loader uses a relocation table to find the segments that need to be adjusted.

Windows

[edit]With 32-bit Windows operating systems, it is not mandatory to provide relocation tables for EXE files, since they are the first image loaded into the virtual address space and thus will be loaded at their preferred base address.

For both DLLs and for EXEs which opt into address space layout randomization (ASLR), an exploit mitigation technique introduced with Windows Vista, relocation tables once again become mandatory because of the possibility that the binary may be dynamically moved before being executed, even though they are still the first thing loaded in the virtual address space.

Windows executables can be marked as ASLR-compatible. The ability exits in Windows 8 and newer to enable ASLR even for applications not marked as compatible.[4] To run successfully in this environment the relocation sections cannot be omitted by the compiler.

Unix-like systems

[edit]The Executable and Linkable Format (ELF) executable and shared library format used by most Unix-like systems allows several types of relocation to be defined.[5]: 1–22

Relocation procedure

[edit]The linker reads segment information and relocation tables in the object files and performs relocation by:

- Merging all segments of common type into a single segment of that type

- Assigning non-overlapping run time addresses to each segment and each symbol, assigning all code (functions) and data (global variables) unique run time addresses

- Referring to the relocation table to modify symbol references in data and object code so that they point to the assigned run-time addresses.

Example

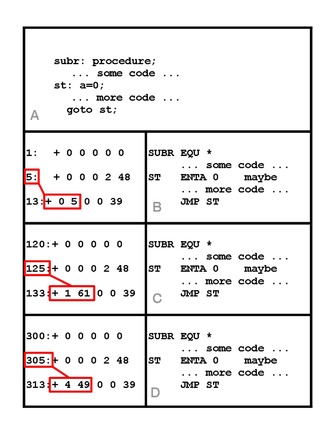

[edit]The following example uses Donald Knuth's MIX architecture and MIXAL assembly language. The principles are the same for any architecture, though the details will change.

- (A) Program SUBR is compiled to produce object file (B), shown as both machine code and assembly. The compiler may designate start of the compiled code at an arbitrary location, often location 1 as shown. Location 13 contains the machine code for the jump instruction to statement ST in location 5.

- (C) If SUBR is later linked with other code it may be stored at a location other than 1. In this example the linker places it at location 120. The address in the jump instruction, which is now at location 133, must be relocated to point to the new location of the code for statement ST, now 125. [1 61 shown in the instruction is the MIX machine code representation of 125].

- (D) When the program is loaded into memory to run it may be loaded at some location other than the one assigned by the linker. This example shows SUBR now at location 300. The address in the jump instruction, now at 313, needs to be relocated again so that it points to the updated location of ST, 305. [4 49 is the MIX machine representation of 305].

Alternatives

[edit]Some architectures avoid relocation entirely by deferring address assignment to run time; as, for example, in stack machines with zero address arithmetic or in some segmented architectures where every compilation unit is loaded into a separate segment.

See also

[edit]- Linker (computing)

- Library (computing)

- Object file

- Prebinding

- Static library

- Self-relocation

- Rebasing

- Garbage collection

- Pointer swizzling, a lazy form of pointer modification

- Relocatable Object Module Format

References

[edit]- ^ "Types of Object Code". iRMX 86 Application Loader Reference Manual (PDF). Intel. pp. 1-2–1-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-11. Retrieved 2020-01-11.

[…] Absolute code, and an absolute object module, is code that has been processed by LOC86 to run only at a specific location in memory. The Loader loads an absolute object module only into the specific location the module must occupy. Position-independent code (commonly referred to as PIC) differs from absolute code in that PIC can be loaded into any memory location. The advantage of PIC over absolute code is that PIC does not require you to reserve a specific block of memory. When the Loader loads PIC, it obtains iRMX 86 memory segments from the pool of the calling task's job and loads the PIC into the segments. A restriction concerning PIC is that, as in the PL/M-86 COMPACT model of segmentation […], it can have only one code segment and one data segment, rather than letting the base addresses of these segments, and therefore the segments themselves, vary dynamically. This means that PIC programs are necessarily less than 64K bytes in length. PIC code can be produced by means of the BIND control of LINK86. Load-time locatable code (commonly referred to as LTL code) is the third form of object code. LTL code is similar to PIC in that LTL code can be loaded anywhere in memory. However, when loading LTL code, the Loader changes the base portion of pointers so that the pointers are independent of the initial contents of the registers in the microprocessor. Because of this fixup (adjustment of base addresses), LTL code can be used by tasks having more than one code segment or more than one data segment. This means that LTL programs may be more than 64K bytes in length. FORTRAN 86 and Pascal 86 automatically produce LTL code, even for short programs. LTL code can be produced by means of the BIND control of LINK86. […]

- ^ a b Levine, John R. (2000) [October 1999]. "Chapter 1: Linking and Loading & Chapter 3: Object Files". Linkers and Loaders. The Morgan Kaufmann Series in Software Engineering and Programming (1 ed.). San Francisco, California, USA: Morgan Kaufmann. p. 5. ISBN 1-55860-496-0. OCLC 42413382. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2020-01-12. Code: [1][2][dead link] Errata: [3]

- ^ Borland (1999-09-01) [1998-07-02]. "Borland article #15961: Coping with 'Fixup Overflow' messages". community.borland.com. Technical Information Database - Product: Borland C++ 3.1. TI961C.txt #15961. Archived from the original on 2008-07-07. Retrieved 2007-01-15.

- ^ "Six Facts about Address Space Layout Randomization on Windows". 2020-03-17. Retrieved 2020-07-24.

- ^ "Executable and Linkable Format (ELF)" (PDF). skyfree.org. Tool Interface Standards (TIS) Portable Formats Specification, Version 1.1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

Further reading

[edit]- Johnson, Glenn (1975-12-21) [1975-11-13]. 11/34 Memory Management Basic Logic test. Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC). MAINDEC-11-DFKTA-A-D. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- Formaniak, Peter G.; Leitch, David (July 1977). "A Proposed Microprocessor Software Standard". BYTE - the small systems journal. Technical Forum. Vol. 2, no. 7. Peterborough, New Hampshire, USA: Byte Publications, Inc. pp. 34, 62–63. ark:/13960/t32245485. Retrieved 2021-12-06. (3 pages) (NB. Describes a relocatable hex format by Mostek.)

- Ogdin, Carol Anne; Colvin, Neil; Pittman, Tom; Tubb, Philip (November 1977). "Relocatable Object Code Formats". BYTE - the small systems journal. Technical Forum. Vol. 2, no. 11. Peterborough, New Hampshire, USA: Byte Publications, Inc. pp. 198–205. ark:/13960/t59c88b4h, ark:/13960/t3kw76j24. Retrieved 2021-12-06. (8 pages) (NB. Describes a relocatable hex format by TDL.)

- Kildall, Gary Arlen (February 1978) [1976]. "A simple technique for static relocation of absolute machine code". Dr. Dobb's Journal of Computer Calisthenics & Orthodontia. 3 (2). People's Computer Company: 10–13 (66–69). ISBN 0-8104-5490-4. #22 ark:/13960/t8hf1g21p. Retrieved 2017-08-19. [4][5][6]. Originally presented at: Kildall, Gary Arlen (1977) [22–24 November 1976]. "A Simple Technique for Static Relocation of Absolute Machine Code". Written at Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, California, USA. In Titus, Harold A. (ed.). Conference Record: Tenth Annual Asilomar Conference on Circuits, Systems and Computers: Papers Presented November 22–24, 1976. Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems & Computers. Asilomar Hotel and Conference Grounds, Pacific Grove, California, USA: Western Periodicals Company. pp. 420–424. ISSN 1058-6393. Retrieved 2021-12-06. (609 pages). (This "resize" method, named page boundary relocation, could be applied statically to a CP/M-80 disk image using MOVCPM in order to maximize the TPA for programs to run. It was also utilized dynamically by the CP/M debugger Dynamic Debugging Tool (DDT) to relocate itself into higher memory. The same approach was independently developed by Bruce H. Van Natta of IMS Associates to produce relocatable PL/M code. As paragraph boundary relocation, another variant of this method was later utilized by dynamically HMA self-relocating TSRs like KEYB, SHARE, and NLSFUNC under DR DOS 6.0 and higher. A much more sophisticated and byte-level granular method based on a somewhat similar approach was independently conceived and implemented by Matthias R. Paul and Axel C. Frinke for their dynamic dead-code elimination to dynamically minimize the runtime footprint of resident drivers and TSRs (like FreeKEYB).)

- Mossip, Richard H. (September–October 1980). Written at Bloomingdale, New Jersey, USA. "Relocatable Code" (PDF). S-100 Microsystems. Vol. 1, no. 5. Mountainside & Springfield, New Jersey, USA: Libes, Inc. pp. 54–55. ISSN 0199-7955. ark:/13960/s2cfgkmxcwg. ark:/13960/s2qdm1t01nr. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-11-27. Retrieved 2023-11-27. [7][8] (2 pages) (NB. Describes page boundary relocation and relocating assemblers.)

- Huitt, Robert; Eubanks, Gordon; Rolander, Thomas "Tom" Alan; Laws, David; Michel, Howard E.; Halla, Brian; Wharton, John Harrison; Berg, Brian; Su, Weilian; Kildall, Scott; Kampe, Bill (2014-04-25). Laws, David (ed.). "Legacy of Gary Kildall: The CP/M IEEE Milestone Dedication" (PDF) (video transscription). Pacific Grove, California, USA: Computer History Museum. CHM Reference number: X7170.2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-12-27. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

[…] Laws: […] "dynamic relocation" of the OS. Can you tell us what that is and why it was important? […] Eubanks: […] what Gary did […] was […] mind boggling. […] I remember the day at the school he came bouncing into the lab and he said, I have figured out how to relocate. He took advantage of the fact that the only byte was always going to be the high order byte. And so he created a bitmap. […] it didn't matter how much memory the computer had, the operating system could always be moved into the high memory. Therefore, you could commercialize this […] on machines of different amounts of memory. […] you couldn't be selling a 64K CP/M and a 47K CP/M. It'd just be ridiculous to have a hard compile in the addresses. So Gary figured this out one night, probably in the middle of the night thinking about some coding thing, and this really made CP/M possible to commercialize. I really think that without that relocation it would have been a very tough problem. To get people to buy it, it'd seem complicated to them, and if you added more memory you'd have to go get a different operating system. […] Intel […] had the bytes reversed, right, for the memory addresses. But they were always in the same place, so you could relocate it on a 256 byte boundary, to be precise. You could therefore always relocate it with just a bitmap of where those […] Laws: Certainly the most eloquent explanation I've ever had of dynamic relocation […]

[9][10] (33 pages) - Lieber, Eckhard; von Massenbach, Thomas (1987). "CP/M 2 lernt dazu. Modulare Systemerweiterungen auch für das 'alte' CP/M". c't - magazin für computertechnik (part 1) (in German). 1987 (1). Heise Verlag: 124–135; Lieber, Eckhard; von Massenbach, Thomas (1987). "CP/M 2 lernt dazu. Modulare Systemerweiterungen auch für das 'alte' CP/M". c't - magazin für computertechnik (part 2) (in German). 1987 (2). Heise Verlag: 78–85; Huck, Alex (2016-10-09). "RSM für CP/M 2.2". Homecomputer DDR (in German). Archived from the original on 2016-11-25. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

- Guzis, Charles "Chuck" P. (2015-03-16). "Re: CP/M assembly language programming". Vintage Computer Forum. Genre: CP/M and MP/M. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

[…] Ever wonder how MOVCPM works? Since the BDOS and CCP is in high memory, above the user application, addresses have to be changed every time the system memory size is changed. Now that requires relocating addresses in 8080 code, since relative addressing is not part of the hardware. Without implementing a full-blown relocating assembler and loader, how does one go about this? It's actually pretty clever and MP/M even uses this scheme to construct its page-relocatable files. You simply assemble the source program twice with the second assembly origin 100H (256 bytes) higher than the first. The two binary images are then compared, byte for byte, and a map constructed of where pairs of bytes differ in value by exactly 100H. The result is a list of locations where the relocation value needs to be adjusted if the location of a program in memory is to be moved. MP/M calls this sort of file PRL (page relocatable), but I don't know that CP/M 2.2 ever coined a name for it. […]

- Guzis, Charles "Chuck" P. (2015-07-29). "Re: How does MOVCPM.COM work?". Vintage Computer Forum. Genre: CP/M and MP/M. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

[…] MOVCPM uses an early type of PRL format. Basically, CP/M is assembled twice; the second time is 100H bytes offset. The two binaries are compared and a bitmap constructed. A set bit implies that the high-order byte of an address is to be adjusted. Low order address bytes are not affected; hence, "Page relocatable file". Each byte in the bitmap corresponds to 8 bytes in the binary data. […] So everything to be moved in MOVCPM is part of the image and its relocation bitmap. […]

- Guzis, Charles "Chuck" P. (2016-11-08). "Re: Is it safe to use RST 28h in CP/M assembly programs?". Vintage Computer Forum. Genre: CP/M and MP/M. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-02-01.

[…] I've referenced PRL files and how they originally got their start with MOVCPM, but became an integral part of MP/M and CP/M 3.0. But PRL files use a bit map in which every bit corresponds to a memory location; one bits indicate that a page relocation offset should be added to the corresponding memory location. If you have very few absolute memory references (as opposed to relative ones) you may want to employ a pointer list (2 bytes per reference) rather than a bitmap. This is unlikely in 8080 code which doesn't have relative jumps, but may be a consideration for Z80 code. The trick to quickly find this out is to assemble your program twice; the second time offset by 100H, then compare the two binaries. The advantage of run-time relocation is that you don't have to incur a penalty for code that attempts to get around the relocation issue--no "tricks"; just write straight code. […]

- Roth, Richard L. (February 1978) [1977]. "Relocation Is Not Just Moving Programs". Dr. Dobb's Journal of Computer Calisthenics & Orthodontia. 3 (2). Ridgefield, California, USA: People's Computer Company: 14–20 (70–76). ISBN 0-8104-5490-4. #22. Archived from the original on 2019-04-20. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

- Calingaert, Peter (1979) [1978-11-05]. "8.2.2 Relocating Loader". Written at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In Horowitz, Ellis (ed.). Assemblers, Compilers, and Program Translation. Computer software engineering series (1st printing, 1st ed.). Potomac, Maryland, USA: Computer Science Press, Inc. pp. 237–241. ISBN 0-914894-23-4. ISSN 0888-2088. LCCN 78-21905. Retrieved 2020-03-20. (2+xiv+270+6 pages)

- The Microsoft OBJ File Format. Microsoft, Product Support Services. Application Note SS0288. Archived from the original on 2017-09-09. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew Stuart; Bos, Herbert (2015). Modern Operating Systems (4 ed.). Pearson Education Inc. ISBN 978-0-13359162-0.

- Elliott, John C. (2012-06-05) [2000-01-02]. "PRL file format". seasip.info. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

[…] A PRL file is a relocatable binary file, used by MP/M and CP/M Plus for various modules other than .COM files. The file format is also used for FID files on the Amstrad PCW. There are several file formats which use versions of PRL: SPR (System PRL), RSP (Resident System Process). LINK-80 can also produce OVL (overlay) files, which have a PRL header but are not relocatable. GSX drivers are in PRL format; so are Resident System Extensions (.RSX). […]

[11] - Elliott, John C. (2012-06-05) [2000-01-02]. "Microsoft REL format". seasip.info. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

[…] The REL format is generated by Microsoft's M80 and Digital Research's RMAC. […]

- feilipu (2018-09-05) [2018-09-02]. "Support for PRL, page relocatable executable for MP/M". z88dk. Archived from the original on 2020-02-01. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

[…] Out of the assembled Microsoft .REL files the linker has to generate a .PRL format executable for MP/M. The .PRL format is essentially a .COM file with some additional information to enable the program and its data to be relocated onto any page. What does a .PRL file look like? The first bytes are size of the program, followed by the program origin at 0x0100. Following the program, there is a bit-for-byte mask appended to allow the MP/M system to know which bytes in the program need to be changed when the program is relocated. How does the linker do that without disassembling the whole application? In advance the program is linked for two different origins 0x0100 and 0x0200, from the .REL objects. The linker trick is simply recognising which bytes in the two versions of the executable differ. These bytes are then recorded in the bit mask stored following the executable, and the final .PRL program is designed to run from 0x0100 plus its page offset. The same trick is done for the .RSP and .SPR executable files, except that both these formats forego the offset, and run from 0x0000 plus their page offset. […]

- Brothers, Hardin (April 1983). "Understanding Relocatable Code". 80 Micro. The Next Step (39). 1001001, Inc.: 38, 40, 42, 45. ISSN 0744-7868. Retrieved 2020-02-06. [12][13]

- Brothers, Hardin (April 1985). "Relocatable Programs: Microcomputing's Hoboes". 80 Micro. The Next Step (63). CW Communications/Peterborough, Inc.: 98, 100, 102–103. ISSN 0744-7868. Retrieved 2020-02-06. [14][15]

- Sage, Jay (May–June 1988). Carlson, Art (ed.). "ZCPR 3.4 - Type-4 Programs". The Computer Journal (TCJ) - Programming, User Support, Applications. ZCPR3 Corner (32). Columbia Falls, Montana, USA: 10–17 [15–16]. ISSN 0748-9331. ark:/13960/t1wd4v943. Retrieved 2021-11-29. [16][17]

- Mitchell, Bridger (July–August 1988). Carlson, Art (ed.). "Z3PLUS & Relocation - Information on ZCPR3PLUS, and how to write self relocating Z80 code". The Computer Journal (TCJ) - Programming, User Support, Applications. Advanced CP/M (33). Columbia Falls, Montana, USA: 9–15. ISSN 0748-9331. ark:/13960/t36121780. Retrieved 2020-02-09. [18][19]

- Sage, Jay (September–October 1988). Carlson, Art (ed.). "More on relocatable code, PRL files, ZCPR34, and Type-4 programs". The Computer Journal (TCJ) - Programming, User Support, Applications. ZCPR3 Corner (34). Columbia Falls, Montana, USA: 20–25. ISSN 0748-9331. ark:/13960/t0ks7pc39. Retrieved 2020-02-09. [20][21][22]

- Sage, Jay (January–February 1992). Carlson, Art; McEwen, Chris (eds.). "Ten Years of ZCPR". The Computer Journal (TCJ) - Programming, User Support, Applications. Z-System Corner (54). S. Plainfield, New Jersey, USA: Socrates Press: 3–7. ISSN 0748-9331. ark:/13960/t89g6n689. Retrieved 2021-11-29. [23][24][25]

- Sage, Jay (May–June 1992) [March–June 1992]. Carlson, Art; McEwen, Chris (eds.). "Type-3 and Type-4 Programs". The Computer Journal (TCJ) - Programming, User Support, Applications. Z-System Corner - Some New Applications of Type-4 Programs (55). S. Plainfield, New Jersey, USA: Socrates Press: 13–19. ISSN 0748-9331. ark:/13960/t4dn54d22. Retrieved 2021-11-29. [26][27]

- Ganssle, Jack (February 1992). "Writing Relocatable Code - Some embedded code must run at more than one address". Embedded Systems Programming. The Ganssle Group - Perfecting the Art of Building Embedded Systems / TGG. Archived from the original on 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

Relocation (computing)

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

In computing, relocation refers to the process of modifying addresses within object code, executables, or libraries to align them with the actual memory locations where the program or module is loaded into memory, which often differs from the assumptions made during compilation.[6] This adjustment ensures that references to code, data, or external symbols function correctly regardless of the final loading position, enabling flexible memory management in operating systems.[7] A key distinction in addressing modes relevant to relocation is between absolute addressing, which embeds fixed memory addresses that require direct modification during relocation, and relative addressing, which uses offsets from a base address and thus needs less adjustment as the base can be shifted uniformly.[6] Relocation primarily targets absolute references to update them to the correct physical or virtual addresses post-loading.[4] Relocation can occur at different stages: static relocation at link time, where the linker resolves and fixes addresses in the final executable; load-time relocation, performed by the operating system's loader to adjust addresses upon program loading into memory; and dynamic relocation at runtime, which handles address mappings during execution, often using hardware mechanisms or for shared libraries.[7] Relocatable object files, produced by compilers, contain unresolved addresses suitable for later relocation, in contrast to position-dependent executables that assume a fixed loading address and may require additional adjustments if moved.[7] Relocation tables record the locations needing adjustment to facilitate this process.[6]Purpose and Necessity

Relocation in computing arises primarily from the limitations of compilers and assemblers, which generate object code assuming a starting address of zero, while actual load addresses in multitasking operating systems remain unpredictable due to variable memory layouts and shared resources among multiple processes. In such environments, programs cannot be bound to fixed physical addresses at compile time, as the operating system must allocate memory dynamically to accommodate concurrent execution and prevent interference. This necessity is addressed through relocation mechanisms that adjust absolute addresses in the code and data sections post-compilation, typically at link time or load time, ensuring the program executes correctly regardless of its final memory position.[8][9] The benefits of relocation extend to enabling dynamic loading, where modules or libraries are incorporated into a running program without requiring full relinking, thus supporting modular software design and reducing overhead in large applications. It facilitates shared libraries by allowing a single instance of code to be loaded once and referenced by multiple processes, with relocation adjusting each process's pointers to the shared memory location, thereby promoting efficient memory utilization and code reuse across the system. By permitting programs to load at arbitrary addresses, relocation optimizes overall memory usage in constrained systems, avoiding fragmentation and enabling higher degrees of multiprogramming.[8] In virtual memory systems, relocation plays a critical role in preventing address conflicts by mapping logical (virtual) addresses generated by processes to distinct physical addresses, enforced through hardware like relocation registers or memory management units (MMUs), which isolate processes and protect the operating system from erroneous access. This separation ensures that each process operates within its own address space, mitigating overlaps that could lead to data corruption or security vulnerabilities in multitasking setups. Additionally, in resource-constrained environments, relocation supports overlays, where non-resident portions of a program are swapped into memory as needed, adjusting addresses to fit the available space without disrupting execution.[9][8] Historically, relocation evolved from the fixed-address assumptions of early mainframe systems in the 1950s, where programs were loaded at predetermined locations, to relocatable code essential for time-sharing systems emerging in the 1960s and 1970s. Pioneering efforts, such as the Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS) on the IBM 7090, incorporated dynamic relocation hardware to manage multiple users' programs in core memory, addressing the inefficiencies of batch processing and enabling interactive computing with flexible memory allocation. This shift was driven by the demands of multiprogramming and time-sharing, where unpredictable load positions became the norm, laying the foundation for modern virtual memory architectures.[10][8]Memory Organization

Position-Dependent Code

Position-dependent code, also referred to as absolute code, consists of machine instructions and data that embed absolute memory addresses resolved and hardcoded during the compilation and linking phases, under the assumption that the program will be loaded into memory at a predetermined fixed base address, such as 0x1000.[11] This approach simplifies code generation by allowing the compiler and linker to produce direct references without additional runtime computations, but it inherently ties the executable's functionality to that specific memory location.[12] In practice, absolute addresses appear in various forms within position-dependent object files and executables. For example, direct branch instructions likeJMP 0x1000 in x86 assembly encode the target location as an absolute offset from the start of memory, assuming the program's base. Similarly, references to global variables or static data involve load and store operations with hardcoded addresses, such as MOV EAX, [0x2000] to access a variable presumed at that location. External symbol calls, resolved by the linker, also result in absolute addresses patched into call instructions, like CALL 0x3000 for a function entry point. These embeddings occur in assembly code or higher-level compilations without relative addressing flags, producing object files where addresses are fixed relative to the assumed base.[13][14]

Loading position-dependent code at an address different from the assumed base renders all embedded absolute references invalid, often causing immediate program failure through mechanisms like invalid instruction fetches, data corruption from erroneous memory accesses, or control flow hijacks leading to crashes. In multi-process environments, this can also result in memory overlaps, where the program's segments collide with those of other running applications, exacerbating resource contention or security vulnerabilities. Relocation serves as the corrective process to dynamically adjust these hardcoded addresses at load time to align with the actual memory placement. By contrast, position-independent code avoids such issues through relative or indirect addressing schemes, enabling flexible loading without per-instance modifications.[12][11]

Segmentation

In computing, segmentation refers to the partitioning of a program into logical sections, each serving a distinct purpose to enable efficient memory management and targeted relocation during loading. Common sections include the .text segment, which contains executable machine code instructions; the .data segment, which holds initialized global and static variables; the .bss segment, which reserves space for uninitialized global and static variables that are zeroed at runtime; and the .rodata segment, which stores read-only constants such as string literals.[15] This division allows the operating system or loader to treat each segment as a self-contained unit, facilitating modular handling in object files like ELF.[15] Relocation in segmented memory models is applied on a per-segment basis, where the base address of each segment is adjusted independently to fit the available physical or virtual memory layout. For instance, the .text segment's base might be shifted to a new location while keeping relative offsets within the segment intact, ensuring that position-dependent code—such as absolute addresses embedded in instructions—requires adjustment only within its own segment boundaries.[16] This approach supports dynamic relocation by allowing segments to be placed non-contiguously, reducing fragmentation and enabling better utilization of memory space compared to treating the entire program as a monolithic block.[16] Historically, segmentation played a key role in architectures like x86, where it supported near pointers (limited to offsets within a single 64 KB segment) and far pointers (combining a segment selector with an offset for addressing up to 1 MB). By isolating changeable parts such as code or data into separate segments, this mechanism minimized relocation overhead, as only affected segments needed base address updates during loading, preserving compatibility and relocatability in real-mode environments.[17] Segmentation originated in early systems from the 1960s, evolving to provide logical partitioning that enhanced relocation flexibility.[16] To ensure proper loading and alignment with hardware requirements, segments must adhere to specific alignment boundaries, often dictated by the target architecture (e.g., 4-byte or 8-byte for x86). Object file formats incorporate padding bytes between or within sections to achieve this alignment, preventing misalignment faults and optimizing access efficiency during relocation. For example, the ELF format explicitly includes padding in section headers to maintain required alignments for subsequent sections.[15]Relocation Data Structures

Relocation Records

A relocation record serves as the basic unit of relocation information in object files, typically structured as a tuple containing an offset, a type, and an addend. The offset specifies the location within a section where the adjustment must be applied, the type indicates the manner of relocation (such as absolute or relative addressing), and the addend provides an initial constant value to be added during resolution.[18] Common relocation types include PC-relative adjustments, such as R_386_PC32, which computes the difference between the symbol's address and the program's counter for branch instructions in x86 architectures, and absolute addressing like R_X86_64_64, which directly places a 64-bit symbol value plus addend at the target location. These types encode operations for symbol resolution and address computation, varying by architecture but generally focusing on how references to external symbols or data are fixed up.[19][20] Relocation records are generated by assemblers and compilers during the symbol resolution phase of object file creation. In a typical two-pass assembly process, the first pass builds a symbol table with labels and their offsets, while the second pass scans the code for unresolved references—such as calls to external functions or data in other sections—and emits a relocation record for each, specifying the section, offset, type, and symbol index to guide later linking.[21] These records are compactly encoded, usually spanning 8 to 24 bytes depending on the architecture and whether an explicit addend is included, and are stored in dedicated sections of the object file, such as .rel for implicit addends or .rela for explicit ones. Records are often aggregated into tables for efficient processing by the linker.[18]Relocation Tables

In computing, relocation tables serve as structured collections of relocation records within object or executable files, organizing them into a contiguous array or dedicated section that lists all necessary adjustments for a module. These tables enable linkers and loaders to efficiently identify and modify address references that depend on the final memory layout. For instance, in the Portable Executable (PE) format, the .reloc section functions as such a table, while in the Executable and Linkable Format (ELF), sections like .rela.dyn fulfill this role.[22][18] The structure of a relocation table varies by file format. In PE, it is organized into blocks indexed by 4 KB memory pages, with each block preceded by a header specifying the Page RVA (base virtual address for the page) and the overall block size (from which the number of 2-byte records can be derived). In ELF, relocation tables are flat arrays of records in dedicated sections, navigated via section headers without internal per-block structures. This organization in PE allows loaders to quickly navigate to relevant portions without parsing the entire file.[23][24][15] Relocation tables are generated during the link-time phase, where the linker merges relocation records from multiple input object files into a unified table tailored to the executable's layout. This consolidation resolves inter-module dependencies and prepares a single, cohesive structure for loader use.[23] By arranging records contiguously, relocation tables facilitate processing efficiency, permitting sequential scanning of entries and batch application of address adjustments in a single pass, which minimizes computational overhead during loading.[23]Platform-Specific Implementations

DOS and 16-bit Windows

In MS-DOS 1.0, released in 1981, the MZ executable format introduced relocation support to enable overlay loading, allowing programs larger than the 64 KB limit of the simpler .COM format by swapping segments in and out of memory as needed.[25] The .EXE file header includes a relocation table offset field at byte 24 (word), pointing to a list of entries that specify locations requiring segment address adjustments during loading.[26] Each relocation entry consists of a 4-byte structure: a 16-bit offset and a 16-bit segment number specifying the location in the executable image requiring adjustment, which the DOS loader uses to add the program's base segment address to hardcoded references, ensuring correct addressing regardless of the load position.[26] This design accommodated the segmented memory model of the x86 real mode, where each segment is limited to 64 KB due to 16-bit offsets, necessitating multiple segments and corresponding fixups for programs exceeding that size.[25] Overlays, managed via the linker option /O, relied on this table to dynamically resolve inter-segment references, with the first overlay loaded by DOS and subsequent ones handled by application code interrupting on a specified vector (default 63h).[27] In 16-bit Windows environments like Windows 3.x, the New Executable (NE) format extended this approach for .EXE and .DLL modules, incorporating fixup tables within the segment table to resolve references across modules.[28] These tables process far pointers—32-bit values combining a 16-bit selector (for protected-mode segment descriptors) and a 16-bit offset—to adjust imports and internal jumps, supporting shared libraries and multitasking under the Virtual DOS Machines (VDM) architecture.[29] The 64 KB segment limit persisted, requiring frequent fixups for any cross-segment access and complicating development for memory-intensive applications, as the system lacked native 32-bit addressing until the transition to 32-bit Windows in the mid-1990s.[30]Modern Windows

In modern Windows operating systems, relocation is primarily managed through the Portable Executable (PE) and Common Object File Format (COFF), where the.reloc section stores base relocation information essential for loading images at addresses different from their preferred base.[22] This section is optional but required for images supporting dynamic loading, and it consists of block-based tables, each aligned to a 4 KB page boundary. Each block begins with a 4-byte Page RVA (Relative Virtual Address) indicating the image base plus the page offset, followed by a 4-byte Block Size specifying the total block length, and then an array of 2-byte WORD entries. These entries encode a relocation type in the high 4 bits and an offset from the Page RVA in the low 12 bits, allowing the loader to adjust addresses efficiently.[24][31]

For 32-bit architectures, the common relocation type IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW (value 3) applies the full 32-bit difference between the actual and preferred base addresses to the 32-bit field at the specified offset.[32] In 64-bit modes (PE32+), types like IMAGE_REL_AMD64_ADDR64 are used instead, applying the 64-bit delta to the target field, ensuring compatibility across Windows' 32-bit and 64-bit executables (EXEs) and dynamic-link libraries (DLLs).[32] Relocations support both EXEs and DLLs by adjusting absolute addresses in code, data, and import/export tables, enabling shared libraries to load at varying bases without recompilation. The PE optional header's DLL Characteristics flag IMAGE_DLLCHARACTERISTICS_DYNAMIC_BASE (0x0040) marks images as relocatable for such scenarios.[33][22]

Relocation integrates closely with Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), a security feature introduced in Windows Vista in 2007 to randomize load bases and mitigate exploits.[34] Since Vista, relocation information became essential for ASLR-enabled images, as the absence of the .reloc section prevents randomization if the preferred base is occupied.[22] In Windows 10 and later, ASLR expanded with system-wide mandatory randomization options, enforced via Windows Defender Exploit Guard or Group Policy, requiring all compatible images to include relocations for full entropy in base address selection.[35] This ensures even legacy or opt-out binaries are relocated if collisions occur, enhancing protection against memory corruption attacks.[35]

The Microsoft Visual C++ linker (link.exe) generates the .reloc section during compilation, with the default behavior stripping relocations from EXEs unless ASLR support is explicitly enabled via the /DYNAMICBASE option.[34] At runtime, the Windows image loader—implemented in ntdll.dll—processes these relocations by calculating the delta between the preferred and actual base, then applying it to each entry in the .reloc table before transferring control to the entry point.[24] This evolved from earlier 16-bit Windows tables by adopting RVA-based blocks for better scalability in protected-mode environments.[22]

Unix-like Systems

In Unix-like systems, the evolution of executable formats significantly influenced relocation mechanisms. The original a.out format, introduced in the 1970s for early Unix implementations, provided basic support for position-dependent executables but lacked robust features for dynamic linking and relocations in shared libraries. This shifted in the late 1980s when Unix System Laboratories (USL) developed the Executable and Linking Format (ELF) as part of the System V Release 4 (SVR4) specification, with widespread adoption across Unix-like operating systems occurring in the 1990s, including in Solaris, IRIX, HP-UX, Linux, and FreeBSD; however, some systems like macOS (based on Darwin) use the Mach-O format instead. ELF addressed limitations of a.out by introducing standardized sections for relocations, enabling more flexible and efficient loading of shared objects.[36][37] The ELF format organizes relocation information in dedicated sections, primarily .rel for entries without explicit addends and .rela for those with explicit addends stored in the r_addend field of Elf32_Rela or Elf64_Rela structures. These sections contain relocation records that specify the location, type, and symbol for adjustments during loading. For example, on x86-64 architectures, the R_X86_64_GLOB_DAT relocation type (value 6) is used to resolve global data symbols by placing their absolute addresses into the Global Offset Table (GOT), facilitating access to global offsets in position-dependent contexts. The dynamic linker processes these entries to update references, ensuring correct addressing in loaded objects.[38][39] In Linux and BSD variants, the dynamic linker—such as ld.so in Linux or rtld-elf.so in FreeBSD—handles relocations at load time for shared objects (.so files). Upon executing a dynamically linked program, the linker identifies dependencies via DT_NEEDED entries in the ELF dynamic section, maps the objects into memory, and applies relocations from .rel(a) sections to resolve symbols and adjust addresses. This process supports both static and dynamic relocations, with the linker rejecting incompatible objects based on ABI versions.[40] Key features in Unix-like ELF implementations enhance efficiency, including lazy binding, where non-essential relocations (e.g., those for functions) are deferred until first use, reducing startup overhead by allowing the linker to skip certain entries during initialization. Additionally, shared library pages are mapped with copy-on-write semantics, enabling multiple processes to share read-only segments while providing private writable copies on modification, thus optimizing memory usage for relocations in multi-process environments.[39][41]Relocation Process

Static Relocation

Static relocation is a process performed by the linker during the linking phase to resolve symbolic references and adjust addresses in relocatable object files, producing a position-dependent executable that is fixed to a specific memory location. This approach embeds all necessary code and data directly into the final binary, eliminating the need for subsequent address adjustments. Unlike dynamic methods, static relocation fully materializes all dependencies at build time, resulting in a self-contained file ready for direct loading into memory at a predetermined base address.[42] The linking process begins with symbol resolution, where the linker associates each undefined reference in the object files with a corresponding definition, handling global symbols such as functions and initialized variables while flagging errors for duplicates or unresolved items. Relocation records from the input object files, which specify offsets needing adjustment, are then scanned to compute absolute addresses by adding section base addresses or offsets to these relative positions. The linker patches the machine code and data directly—updating instruction operands, jump targets, and variable references—merging sections like.text and .data into contiguous blocks without retaining relocation information in the output executable.[42][43]

This technique is particularly suited for standalone executables that operate without shared libraries, as it resolves all inter-module dependencies upfront, ensuring portability across systems with compatible loaders but requiring recompilation for different base addresses. Tools such as the GNU linker ld, which processes ELF object files to generate fixed binaries, and Microsoft link.exe, used in Visual Studio for producing position-dependent PE executables, implement this phase as a core function.[42][43]

Load-Time Relocation

Load-time relocation occurs during the runtime loading of executable images or shared libraries by the operating system's dynamic loader, adjusting absolute addresses to fit the actual memory location when the preferred base address is unavailable. This process ensures that references within the loaded module, such as pointers to data or code, are correctly resolved relative to the final load position. Unlike compile-time or link-time fixes, load-time relocation defers adjustments until the module is mapped into process memory, allowing flexibility in address assignment.[44] The loader initiates the process by mapping the image into virtual memory at an available base address, then reads the relocation table—such as the .reloc section in PE format or .rela.dyn in ELF—to identify entries requiring adjustment. For each entry, it computes the delta as the difference between the actual load base and the preferred base (new_base - preferred_base), adding this value plus any section-specific offset to the target location in memory. In PE files, relocations are organized into page-based blocks, where each block specifies a virtual address and a list of type-offset pairs (e.g., IMAGE_REL_BASED_HIGHLOW for 32-bit absolute adjustments), enabling the loader to apply the delta efficiently across 4KB pages. Similarly, in ELF, the loader processes relocation records by type (e.g., R_386_32 for absolute additions or R_386_PC32 for PC-relative offsets), updating pointers or instructions directly. This step-by-step application ensures the image becomes self-consistent without altering the original file on disk.[22][44][45] For dynamic cases involving imports from shared libraries (DLLs in Windows or .so files in Unix-like systems), the loader relocates indirect references using structures like the Global Offset Table (GOT) and Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) in ELF. The GOT holds runtime-resolved addresses for external symbols, while the PLT provides stubs for function calls that initially jump to a lazy binder; upon first invocation, the binder resolves the symbol and updates the corresponding GOT entry with the actual address, avoiding repeated relocations. In PE, the Import Address Table (IAT) serves a similar role, with the loader updating it during binding to point to imported functions in loaded DLLs. These mechanisms support deferred or lazy binding, where not all imports are resolved immediately, reducing initial load overhead. Brief reference to platform-specific tables, such as ELF's .rela sections, underscores how these structures encode the offsets and types needed for such adjustments.[46][22] Error handling during load-time relocation addresses failures such as unresolved symbols or arithmetic overflows. If a required symbol from a dependency cannot be located, the loader aborts the process and reports an error, preventing execution with incomplete references; for instance, GNU ld and dynamic loaders like ld.so treat unresolved dynamic symbols as fatal unless configured otherwise. Overflows occur when the computed adjustment exceeds the bit width of the target field, such as in 64-bit systems using 32-bit relative relocations (e.g., R_X86_64_PC32), potentially causing memory corruption; the loader may fail the load or truncate the value, depending on the platform, with warnings often issued at link time to preempt runtime issues. In PE, if relocations are stripped and the preferred base is unavailable, loading fails outright.[47][48][22] To optimize performance and minimize startup time, loaders process relocations in batches, typically by section or page, applying adjustments en masse before transferring control to the program's entry point. This batched approach, as seen in ELF's sequential handling of .rela entries or PE's page-aligned blocks, reduces context switches and memory accesses, though it can still contribute to delays in large applications with extensive relocation tables. Eager binding resolves all entries upfront for predictability, while lazy binding defers non-critical ones, trading minor runtime costs for faster initial loads.[44][46][49]Examples

Basic Relocation Example

To illustrate basic absolute relocation, consider a simple hypothetical program compiled for a 32-bit x86-like architecture, assuming it will be loaded at memory base address 0x1000. The program's code begins at this base, and at offset 0x10 from the start (absolute address 0x1010 during compilation), there is an instructionmov eax, [global_var] that references a global variable located at absolute address 0x2000. In the object file's machine code, this instruction appears as the opcode A1 (for loading from memory into EAX) followed by the 4-byte little-endian representation of 0x2000, yielding a hex dump segment of A1 00 20 00 00 at that offset.[8]

The corresponding relocation record in the object file specifies an absolute type (indicating a direct address adjustment), with the offset 0x10 (relative to the code section start) and an addend of 0x2000 (the original address value embedded in the instruction). This record informs the loader of the location and value needing modification to account for the actual load address.[8]

When the loader places the program at base address 0x4000 instead of the assumed 0x1000, it computes the relocation delta as 0x3000 (0x4000 - 0x1000) and applies it by adding this value to the addend in the record. The adjusted address becomes 0x2000 + 0x3000 = 0x5000, and the loader patches the instruction's address field to 0x5000, updating the hex to A1 00 50 00 00. Before adjustment, the code assumes the variable at absolute address 0x2000 given the expected base; after, it correctly references 0x5000, where the global variable is also relocated in the new memory layout.[8]

As a result, the program executes correctly, with the instruction now loading from the relocated global variable's position, demonstrating how absolute relocation ensures compatibility across different memory placements without recompilation.[8]

Segmented Relocation Example

In a typical segmented relocation example, consider a program compiled and linked for an x86 real-mode environment, such as under MS-DOS, where the code segment (.text) is positioned at segment address 0x0000 and the data segment (.data) at 0x0010 (one paragraph, or 16 bytes, apart) in the executable file assuming a base load segment of 0x0000. Within the .text segment, a far call instruction references a location in .data at offset 0x0020; this instruction stores the target far pointer as segment 0x0010 followed by offset 0x0020, with the segment word located at offset 0x10 within the overall load module. The relocation table records this inter-segment fixup with a 4-byte entry: the first word (0x0000) indicating the byte offset within the paragraph, and the second word (0x0001) indicating the paragraph offset into the load module (0x001 * 0x10 = 0x10).[25] During loading, the operating system allocates memory and places the entire load module starting at an actual base segment of 0x4000, shifting both .text to 0x4000 and .data to 0x4010 to maintain their relative positioning. The loader processes the relocation table sequentially: for the entry at file offset specified in the header, it computes the memory address as (entry.paragraph * 0x10) + entry.offset, reads the 16-bit value there (originally 0x0010), adds the base segment (0x4000), and writes back the adjusted value (0x4010). This updates the far call's segment field, ensuring the instruction now targets the correct relocated .data location. The process can be represented in pseudo-code as:base_segment = 0x4000 // Actual load base

relocation_table_offset = header.reloc_offset // From EXE header

num_relocations = header.num_reloc_items

for i from 0 to num_relocations - 1:

entry_offset = relocation_table_offset + (i * 4)

reloc_offset = read_word(entry_offset) // e.g., 0x0000

reloc_paragraph = read_word(entry_offset + 2) // e.g., 0x0001

target_address = (reloc_paragraph * 0x10) + reloc_offset // e.g., 0x10

memory_value = read_word_at_load_module(target_address) // e.g., 0x0010

adjusted_value = memory_value + base_segment // e.g., 0x4010

write_word_at_load_module(target_address, adjusted_value)

base_segment = 0x4000 // Actual load base

relocation_table_offset = header.reloc_offset // From EXE header

num_relocations = header.num_reloc_items

for i from 0 to num_relocations - 1:

entry_offset = relocation_table_offset + (i * 4)

reloc_offset = read_word(entry_offset) // e.g., 0x0000

reloc_paragraph = read_word(entry_offset + 2) // e.g., 0x0001

target_address = (reloc_paragraph * 0x10) + reloc_offset // e.g., 0x10

memory_value = read_word_at_load_module(target_address) // e.g., 0x0010

adjusted_value = memory_value + base_segment // e.g., 0x4010

write_word_at_load_module(target_address, adjusted_value)

| Element | Linked Segment:Offset | Loaded Segment:Offset | Adjustment Applied |

|---|---|---|---|

| .text segment | 0x0000:0000 | 0x4000:0000 | +0x4000 to segment |

| .data segment | 0x0010:0000 | 0x4010:0000 | +0x4000 to segment |

| Far call target | 0x0010:0020 | 0x4010:0020 | +0x4000 to segment only |

Modern Alternatives

Position-Independent Code

Position-independent code (PIC) is a compilation technique that generates machine code capable of executing correctly regardless of its absolute load address in memory, thereby reducing or eliminating the need for traditional relocation during loading. This is achieved primarily through the use of relative addressing modes, where instructions reference locations relative to the current program counter (PC), such as PC-relative jumps and branches that compute offsets from the instruction's position. For data accesses, particularly to global variables and external symbols, PIC employs the Global Offset Table (GOT), a runtime-modifiable data structure that stores absolute addresses resolved by the dynamic linker at load time or lazily during execution.[39][51] In practice, compilers like GCC generate PIC using the-fPIC flag, which produces code suitable for shared libraries by favoring relative addressing and GOT indirection for all external references, ensuring the text section remains read-only and shareable across processes. This approach limits load-time fixups to only the GOT entries and Procedure Linkage Table (PLT) for function calls, rather than patching the code itself. As a result, relocation tables in PIC-enabled ELF object files are reduced to entries for dynamic symbols only, minimizing processing overhead.[51][39]

The advantages of PIC include enabling address space layout randomization (ASLR) for security by allowing flexible loading without code modification, as well as faster startup times due to reduced relocation work, making it the standard for shared object (.so) files in the ELF format. However, PIC introduces a slight runtime overhead from the indirection required for GOT and PLT accesses, which can add a few cycles per external reference compared to direct addressing in position-dependent code. This technique was introduced in the 1980s for Unix shared libraries, notably in SunOS, to support efficient dynamic linking and code sharing.[39][52]