Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Interpreter (computing)

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2025) |

| Program execution |

|---|

| General concepts |

| Types of code |

| Compilation strategies |

| Notable runtimes |

|

| Notable compilers & toolchains |

|

In computing, an interpreter is software that executes source code without first compiling it to machine code. Interpreted languages differ from compiled languages, which involve the translation of source code into CPU-native executable code. Depending on the runtime environment, interpreters may first translate the source code to an intermediate format, such as bytecode. Hybrid runtime environments may also translate the bytecode into machine code via just-in-time compilation, as in the case of .NET and Java, instead of interpreting the bytecode directly.

Before the widespread adoption of interpreters, the execution of computer programs often relied on compilers, which translate and compile source code into machine code. Early runtime environments for Lisp and BASIC could parse source code directly. Thereafter, runtime environments were developed for languages (such as Perl, Raku, Python, MATLAB, and Ruby), which translated source code into an intermediate format before executing to enhance runtime performance.

Code that runs in an interpreter can be run on any platform that has a compatible interpreter. The same code can be distributed to any such platform, instead of an executable having to be built for each platform. Although each programming language is usually associated with a particular runtime environment, a language can be used in different environments. Interpreters have been constructed for languages traditionally associated with compilation, such as ALGOL, Fortran, COBOL, C and C++.

History

[edit]In the early days of computing, compilers were more commonly found and used than interpreters because hardware at that time could not support both the interpreter and interpreted code and the typical batch environment of the time limited the advantages of interpretation.[1]

Interpreters were used as early as 1952 to ease programming within the limitations of computers at the time (e.g. a shortage of program storage space, or no native support for floating point numbers). Interpreters were also used to translate between low-level machine languages, allowing code to be written for machines that were still under construction and tested on computers that already existed.[2] The first interpreted high-level language was Lisp. Lisp was first implemented by Steve Russell on an IBM 704 computer. Russell had read John McCarthy's paper, "Recursive Functions of Symbolic Expressions and Their Computation by Machine, Part I", and realized (to McCarthy's surprise) that the Lisp eval function could be implemented in machine code.[3] The result was a working Lisp interpreter which could be used to run Lisp programs, or more properly, "evaluate Lisp expressions".

The development of editing interpreters was influenced by the need for interactive computing. In the 1960s, the introduction of time-sharing systems allowed multiple users to access a computer simultaneously, and editing interpreters became essential for managing and modifying code in real-time. The first editing interpreters were likely developed for mainframe computers, where they were used to create and modify programs on the fly. One of the earliest examples of an editing interpreter is the EDT (Editor and Debugger for the TECO) system, which was developed in the late 1960s for the PDP-1 computer. EDT allowed users to edit and debug programs using a combination of commands and macros, paving the way for modern text editors and interactive development environments.[citation needed]

Use

[edit]Notable uses for interpreters include:

- Virtualization

- An interpreter acts as a virtual machine to execute machine code for a hardware architecture different from the one running the interpreter.

- Emulation

- An interpreter (virtual machine) can emulate another computer system in order to run code written for that system.

- Sandboxing

- While some types of sandboxes rely on operating system protections, an interpreter (virtual machine) can offer additional control such as blocking code that violates security rules.[citation needed]

- Self-modifying code

- Self-modifying code can be implemented in an interpreted language. This relates to the origins of interpretation in Lisp and artificial intelligence research.[citation needed]

Efficiency

[edit]Interpretive overhead is the runtime cost of executing code via an interpreter instead of as native (compiled) code. Interpreting is slower because the interpreter executes multiple machine-code instructions for the equivalent functionality in the native code. In particular, access to variables is slower in an interpreter because the mapping of identifiers to storage locations must be done repeatedly at run-time rather than at compile time.[4] But faster development (due to factors such as shorter edit-build-run cycle) can outweigh the value of faster execution speed; especially when prototyping and testing when the edit-build-run cycle is frequent.[4][5]

An interpreter may generate an intermediate representation (IR) of the program from source code in order to achieve goals such as fast runtime performance. A compiler may also generate an IR, but the compiler generates machine code for later execution whereas the interpreter prepares to execute the program. These differing goals lead to differing IR design. Many BASIC interpreters replace keywords with single byte tokens which can be used to find the instruction in a jump table.[4] A few interpreters, such as the PBASIC interpreter, achieve even higher levels of program compaction by using a bit-oriented rather than a byte-oriented program memory structure, where commands tokens occupy perhaps 5 bits, nominally "16-bit" constants are stored in a variable-length code requiring 3, 6, 10, or 18 bits, and address operands include a "bit offset". Many BASIC interpreters can store and read back their own tokenized internal representation.

There are various compromises between the development speed when using an interpreter and the execution speed when using a compiler. Some systems (such as some Lisps) allow interpreted and compiled code to call each other and to share variables. This means that once a routine has been tested and debugged under the interpreter it can be compiled and thus benefit from faster execution while other routines are being developed.[citation needed]

Implementation

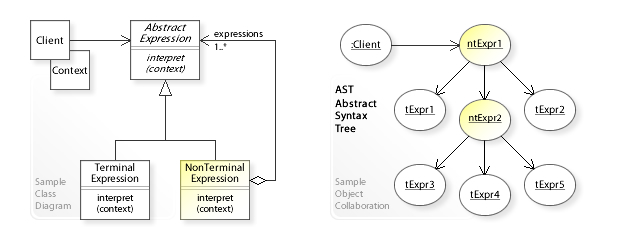

[edit]Since the early stages of interpreting and compiling are similar, an interpreter might use the same lexical analyzer and parser as a compiler and then interpret the resulting abstract syntax tree.

Example

[edit]An expression interpreter written in C++.

import std;

using std::runtime_error;

using std::unique_ptr;

using std::variant;

// data types for abstract syntax tree

enum class Kind: char {

VAR,

CONST,

SUM,

DIFF,

MULT,

DIV,

PLUS,

MINUS,

NOT

};

// forward declaration

class Node;

class Variable {

public:

int* memory;

};

class Constant {

public:

int value;

};

class UnaryOperation {

public:

unique_ptr<Node> right;

};

class BinaryOperation {

public:

unique_ptr<Node> left;

unique_ptr<Node> right;

};

using Expression = variant<Variable, Constant, BinaryOperation, UnaryOperation>;

class Node {

public:

Kind kind;

Expression e;

};

// interpreter procedure

[[nodiscard]]

int executeIntExpression(const Node& n) {

int leftValue;

int rightValue;

switch (n->kind) {

case Kind::VAR:

return std::get<Variable>(n.e).memory;

case Kind::CONST:

return std::get<Constant>(n.e).value;

case Kind::SUM:

case Kind::DIFF:

case Kind::MULT:

case Kind::DIV:

const BinaryOperation& bin = std::get<BinaryOperation>(n.e);

leftValue = executeIntExpression(bin.left.get());

rightValue = executeIntExpression(bin.right.get());

switch (n.kind) {

case Kind::SUM:

return leftValue + rightValue;

case Kind::DIFF:

return leftValue - rightValue;

case Kind::MULT:

return leftValue * rightValue;

case Kind::DIV:

if (rightValue == 0) {

throw runtime_error("Division by zero");

}

return leftValue / rightValue;

}

case Kind::PLUS:

case Kind::MINUS:

case Kind::NOT:

const UnaryOperation& un = std::get<UnaryOperation>(n.e);

rightValue = executeIntExpression(un.right.get());

switch (n.kind) {

case Kind::PLUS:

return +rightValue;

case Kind::MINUS:

return -rightValue;

case Kind::NOT:

return !rightValue;

}

default:

std::unreachable();

}

}

Just-in-time compilation

[edit]Just-in-time (JIT) compilation is the process of converting an intermediate format (i.e. bytecode) to native code at runtime. As this results in native code execution, it is a method of avoiding the runtime cost of using an interpreter while maintaining some of the benefits that lead to the development of interpreters.

Variations

[edit]- Control table interpreter

- Logic is specified as data formatted as a table.

- Bytecode interpreter

- Some interpreters process bytecode which is an intermediate format of logic compiled from a high-level language. For example, Emacs Lisp is compiled to bytecode which is interpreted by an interpreter. One might say that this compiled code is machine code for a virtual machine – implemented by the interpreter. Such an interpreter is sometimes called a compreter.[6][7]

- Threaded code interpreter

- A threaded code interpreter is similar to bytecode interpreter but instead of bytes, uses pointers. Each instruction is a word that points to a function or an instruction sequence, possibly followed by a parameter. The threaded code interpreter either loops fetching instructions and calling the functions they point to, or fetches the first instruction and jumps to it, and every instruction sequence ends with a fetch and jump to the next instruction. One example of threaded code is the Forth code used in Open Firmware systems. The source language is compiled into "F code" (a bytecode), which is then interpreted by a virtual machine.[citation needed]

- Abstract syntax tree interpreter

- An abstract syntax tree interpreter transforms source code into an abstract syntax tree (AST), then interprets it directly, or uses it to generate native code via JIT compilation.[8] In this approach, each sentence needs to be parsed just once. As an advantage over bytecode, AST keeps the global program structure and relations between statements (which is lost in a bytecode representation), and when compressed provides a more compact representation.[9] Thus, using AST has been proposed as a better intermediate format than bytecode. However, for interpreters, AST results in more overhead than a bytecode interpreter, because of nodes related to syntax performing no useful work, of a less sequential representation (requiring traversal of more pointers) and of overhead visiting the tree.[10]

- Template interpreter

- Rather than implement the execution of code by virtue of a large switch statement containing every possible bytecode, while operating on a software stack or a tree walk, a template interpreter maintains a large array of bytecode (or any efficient intermediate representation) mapped directly to corresponding native machine instructions that can be executed on the host hardware as key value pairs (or in more efficient designs, direct addresses to the native instructions),[11][12] known as a "Template". When the particular code segment is executed the interpreter simply loads or jumps to the opcode mapping in the template and directly runs it on the hardware.[13][14] Due to its design, the template interpreter very strongly resembles a JIT compiler rather than a traditional interpreter, however it is technically not a JIT due to the fact that it merely translates code from the language into native calls one opcode at a time rather than creating optimized sequences of CPU executable instructions from the entire code segment. Due to the interpreter's simple design of simply passing calls directly to the hardware rather than implementing them directly, it is much faster than every other type, even bytecode interpreters, and to an extent less prone to bugs, but as a tradeoff is more difficult to maintain due to the interpreter having to support translation to multiple different architectures instead of a platform independent virtual machine/stack. To date, the only template interpreter implementations of widely known languages to exist are the interpreter within Java's official reference implementation, the Sun HotSpot Java Virtual Machine,[11] and the Ignition Interpreter in the Google V8 JavaScript execution engine.

- Microcode

- Microcode provides an abstraction layer as a hardware interpreter that implements machine code in a lower-level machine code.[15] It separates the high-level machine instructions from the underlying electronics so that the high-level instructions can be designed and altered more freely. It also facilitates providing complex multi-step instructions, while reducing the complexity of computer circuits.

See also

[edit]- Dynamic compilation

- Homoiconicity – Characteristic of a programming language

- Meta-circular evaluator – Type of interpreter in computing

- Partial evaluation – Technique for program optimization

- Read–eval–print loop – Computer programming environment

References

[edit]- ^ "Why was the first compiler written before the first interpreter?". Ars Technica. 8 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ Bennett, J. M.; Prinz, D. G.; Woods, M. L. (1952). "Interpretative sub-routines". Proceedings of the ACM National Conference, Toronto.

- ^ According to what reported by Paul Graham in Hackers & Painters, p. 185, McCarthy said: "Steve Russell said, look, why don't I program this eval..., and I said to him, ho, ho, you're confusing theory with practice, this eval is intended for reading, not for computing. But he went ahead and did it. That is, he compiled the eval in my paper into IBM 704 machine code, fixing bug, and then advertised this as a Lisp interpreter, which it certainly was. So at that point Lisp had essentially the form that it has today..."

- ^ a b c This article is based on material taken from Interpreter at the Free On-line Dictionary of Computing prior to 1 November 2008 and incorporated under the "relicensing" terms of the GFDL, version 1.3 or later.

- ^ "Compilers vs. interpreters: explanation and differences". IONOS Digital Guide. Retrieved 2022-09-16.

- ^ Kühnel, Claus (1987) [1986]. "4. Kleincomputer - Eigenschaften und Möglichkeiten" [4. Microcomputer - Properties and possibilities]. In Erlekampf, Rainer; Mönk, Hans-Joachim (eds.). Mikroelektronik in der Amateurpraxis [Micro-electronics for the practical amateur] (in German) (3 ed.). Berlin: Militärverlag der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Leipzig. p. 222. ISBN 3-327-00357-2. 7469332.

- ^ Heyne, R. (1984). "Basic-Compreter für U880" [BASIC compreter for U880 (Z80)]. radio-fernsehn-elektronik (in German). 1984 (3): 150–152.

- ^ AST intermediate representations, Lambda the Ultimate forum

- ^ Kistler, Thomas; Franz, Michael (February 1999). "A Tree-Based Alternative to Java Byte-Codes" (PDF). International Journal of Parallel Programming. 27 (1): 21–33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.87.2257. doi:10.1023/A:1018740018601. ISSN 0885-7458. S2CID 14330985. Retrieved 2020-12-20.

- ^ Surfin' Safari - Blog Archive » Announcing SquirrelFish. Webkit.org (2008-06-02). Retrieved on 2013-08-10.

- ^ a b "openjdk/jdk". GitHub. 18 November 2021.

- ^ "HotSpot Runtime Overview". Openjdk.java.net. Retrieved 2022-08-06.

- ^ "Demystifying the JVM: JVM Variants, Cppinterpreter and TemplateInterpreter". metebalci.com.

- ^ "JVM template interpreter". ProgrammerSought.

- ^ Kent, Allen; Williams, James G. (April 5, 1993). Encyclopedia of Computer Science and Technology: Volume 28 - Supplement 13. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. ISBN 0-8247-2281-7. Retrieved Jan 17, 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Aycock, J. (June 2003). "A brief history of just-in-time". ACM Computing Surveys. 35 (2): 97–113. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.97.3985. doi:10.1145/857076.857077. S2CID 15345671.

External links

[edit]- IBM Card Interpreters page at Columbia University

- Theoretical Foundations For Practical 'Totally Functional Programming' (Chapter 7 especially) Doctoral dissertation tackling the problem of formalising what is an interpreter

Interpreter (computing)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

An interpreter in computing is a software program that executes high-level source code written in a programming language by translating and running it instruction by instruction, often using an intermediate representation such as bytecode, without first generating a separate standalone executable file. Typically, it processes the code in structured units, such as expressions or statements, performing the corresponding machine-level operations on the fly to produce output or effects. This approach contrasts with compilation, where the entire program is translated ahead of time into machine code.[5][11] The primary purpose of an interpreter is to facilitate immediate program execution, enabling rapid prototyping, interactive debugging, and deployment in scenarios where full compilation is impractical or unnecessary, such as in scripting environments or dynamic languages. By allowing developers to run and modify code incrementally, interpreters support efficient experimentation and error correction during development, reducing the time between writing code and observing results. This makes them particularly valuable for educational tools, exploratory programming, and systems requiring quick iterations.[12][13] Key characteristics of interpreters include their on-the-fly translation from source code to execution, which often accommodates dynamic typing—where data types are resolved at runtime rather than compile time—and enables runtime modifications, such as altering program behavior or loading new code dynamically in supported languages. These features enhance flexibility but can introduce performance trade-offs compared to pre-compiled execution. Interpreters originated as an accessible alternative to compilers, promoting interactive computing and broadening programming usability in early systems.[14][15]Comparison to Compilers

Interpreters execute source code by translating it on the fly, often to an intermediate representation like bytecode, without generating a standalone machine code executable, whereas compilers translate the entire source code into machine code ahead of time.[16][17] This fundamental distinction means that interpreters process and run the code expression by expression or statement by statement during runtime, allowing for immediate execution without a prior full translation phase.[1] In contrast, compilers perform a complete analysis and translation of the program into an executable form before any execution occurs.[4] The workflows of interpreters and compilers differ significantly in terms of development and runtime processes. Interpreters enable immediate execution of code changes, facilitating rapid prototyping and easier error detection as issues are identified and reported during the execution of specific statements.[18] Compilers, however, require a separate compilation step to produce machine code, which can delay testing but results in faster runtime performance once the program is built.[4] Many modern systems employ hybrid approaches that combine elements of both interpreters and compilers to balance their strengths, such as translating code to an intermediate form for interpretation.[19] Interpreters offer greater flexibility and portability, as the same source code can run on any platform with a compatible interpreter, without needing recompilation.[4] Compilers emphasize speed and optimization by generating highly efficient machine code tailored to specific hardware.[5] For example, Python's CPython implementation primarily uses an interpreter to execute bytecode directly, while Cython acts in a compiler-like manner by translating Python code to C for ahead-of-time compilation into machine code.[17]Historical Development

Early Interpreters

The development of early interpreters in computing emerged in the mid-1950s, driven by the need to simplify programming for scientific and engineering applications beyond low-level machine code or assembly. One of the pioneering systems was the Wolontis-Bell Interpreter, developed at Bell Labs for the IBM 650 computer around 1956–1957. Created by Michael Wolontis and colleagues, this interpreter supported the L1 language, an early list-processing system influenced by algebraic expression handling and symbolic manipulation, allowing users to write higher-level code that was executed directly without prior compilation.[20] The motivations behind such systems stemmed from the desire for more accessible tools in research environments, where the flexibility of direct execution outweighed performance concerns, particularly in domains requiring rapid prototyping and symbolic computation.[21] Building on these foundations, John McCarthy introduced an early Lisp interpreter in 1958 as part of his work on programming languages for artificial intelligence at MIT. This interpreter, implemented by student Steve Russell, enabled the evaluation of symbolic expressions in a recursive manner, marking a significant step toward languages supporting list processing and AI experimentation. The design prioritized conceptual elegance for symbolic operations over execution speed, reflecting the era's focus on AI research where dynamic evaluation facilitated iterative development of algorithms for pattern matching and logical inference. McCarthy's work formalized Lisp's core evaluator as a universal function, allowing the language to interpret its own expressions, which underscored the interpreter's role in enabling self-referential computation.[22][23] A key milestone came in 1964 with the Dartmouth BASIC interpreter, developed by John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz for the GE-225 time-sharing system at Dartmouth College. This interpreter allowed multiple users to interactively program in a simple algebraic language via remote terminals, executing statements line-by-line and providing immediate feedback, which was revolutionary for non-expert users. The system was motivated by the goal of broadening access to computing in education, enabling students across disciplines to engage with programming without deep technical knowledge, thus fostering interactive computing on shared resources. Early designs of these interpreters, including Lisp and BASIC, often employed simple recursive descent parsing techniques to process source code, where the parser recursively matches grammar rules in a top-down manner, suitable for the relatively straightforward syntax of these languages. The impact of these early interpreters was profound, as they democratized programming by abstracting away machine-specific details and assembly language complexities, thereby influencing computer science education and research. Systems like the Lisp interpreter advanced AI and symbolic computation fields, while BASIC's interactive model inspired widespread adoption in teaching, paving the way for time-sharing and personal computing paradigms in subsequent decades.[22][24]Evolution in Programming Languages

In the late 1970s and 1980s, interpreters evolved to support scripting languages that facilitated rapid text processing and system automation, building on earlier foundational systems like BASIC. Perl, developed by Larry Wall and first released on December 18, 1987, introduced an interpreter designed for practical extraction and reporting tasks, enabling efficient handling of unstructured data in Unix environments.[25] This scripting focus made Perl a staple for system administration and web CGI scripts. Similarly, Python's interpreter, created by Guido van Rossum and released on February 20, 1991, emphasized readability and versatility for general-purpose scripting, quickly gaining traction for its ease in prototyping applications.[26] Meanwhile, Smalltalk's virtual machine, introduced in the Smalltalk-80 system in 1980, profoundly influenced interpreter design by demonstrating how a bytecode-interpreting VM could enable dynamic, object-oriented environments with live reprogramming capabilities, paving the way for portable execution models in later languages. The 1990s and 2000s saw interpreters adapt to the burgeoning web ecosystem, prioritizing client-side interactivity and server-side dynamism. SpiderMonkey, the first JavaScript engine developed by Brendan Eich at Netscape in 1995 and integrated into browsers by 1998, revolutionized web development by interpreting JavaScript for real-time page manipulation, enabling dynamic user interfaces without full page reloads. PHP, initially created by Rasmus Lerdorf in 1994 and formalized in 1995, provided a server-side interpreter embedded in HTML for generating dynamic content, such as personalized web pages and database-driven applications, which powered much of the early internet's interactive backend. These advancements democratized web scripting, allowing developers to iterate quickly on content delivery systems. From the 2010s onward, interpreters have integrated into diverse platforms like mobile, cloud, and serverless environments, supporting high-velocity development in modern computing. The V8 engine, originally developed by Google in 2008 and powering Node.js since 2009, saw significant advancements in the 2010s, including the 2010 introduction of the Crankshaft optimizing compiler, which boosted runtime performance for server-side JavaScript in event-driven applications.[27] Lua's lightweight interpreter has become prominent in mobile game development, as seen in frameworks like Corona SDK (introduced in 2009), where it enables efficient scripting for cross-platform titles on iOS and Android, handling game logic with minimal resource overhead. In data science, Jupyter Notebooks, evolved from the IPython project in 2011, leverage interpreters like Python's to facilitate interactive workflows, allowing researchers to execute code cells incrementally for exploratory analysis and visualization in cloud-based environments.[28] These evolutions have been driven by the explosive growth of the web, mobile apps, and AI/ML workflows, where interpreters enable rapid iteration through immediate feedback loops and dynamic code execution, contrasting with slower compile cycles in static languages. A key trend is the shift toward hybrid interpreter-compiler models, such as just-in-time (JIT) compilation in V8, to balance performance and flexibility, yet pure interpreters remain vital in resource-constrained domains like embedded systems and IoT devices, where Lua's embeddability supports low-footprint scripting for sensor networks and edge computing.[29]Operational Principles

Execution Mechanism

The execution mechanism of an interpreter in computing involves a series of sequential phases that process and run source code directly, without producing a separate executable file. The process begins with lexical analysis, where the source code—a stream of characters—is scanned and broken into meaningful units called tokens, such as keywords, identifiers, operators, and literals. This step eliminates whitespace and comments, producing a sequence of tokens that represent the program's structure in a simplified form.[30] Following lexical analysis is syntax analysis, also known as parsing, which examines the token sequence to verify adherence to the language's grammar rules and constructs a parse tree or abstract syntax tree (AST) representing the hierarchical structure of the program. This phase detects syntactic errors, such as mismatched parentheses or invalid statement orders, and builds an intermediate representation that captures the code's syntactic validity. Next comes semantic analysis, which performs deeper checks on the parse tree to ensure the code's meaning is consistent with the language's semantics; this includes type checking, verifying variable declarations, resolving scopes, and building a symbol table to track identifiers and their attributes like types and memory locations.[30][31] Once analysis is complete, the interpreter proceeds to direct execution, where it traverses the parse tree or AST and performs the corresponding actions for each node, such as evaluating expressions, assigning values to variables, or invoking functions, all within the host machine's environment. Unlike compilers, this execution happens immediately after analysis, often statement by statement or expression by expression, allowing for dynamic behavior like runtime type resolution. The runtime environment supports this by maintaining data structures such as symbol tables for name resolution and stacks for managing variable scopes, function call activations, and control flow; for instance, a call stack pushes activation records during function invocations to store local variables and return addresses, popping them upon completion. This environment also facilitates interactive error handling, where exceptions or undefined behaviors trigger immediate feedback rather than halting the entire program.[30][31] Interpreters operate in two primary modes: batch mode, which processes an entire script file sequentially from start to finish, and interactive mode, exemplified by the Read-Eval-Print Loop (REPL), where the system repeatedly reads user input, evaluates it, prints the result, and loops back for more input, enabling immediate experimentation and debugging. In a REPL, each cycle performs the full analysis-execution pipeline on small code snippets, providing instant feedback that accelerates development and learning.[30][32] A simplified pseudocode illustration of the interpreter's core fetch-execute cycle for processing statements in a program might resemble the following loop, assuming a parsed representation like an AST:while not end of program:

fetch next statement from AST

if statement is valid:

execute action (e.g., evaluate expression, update [symbol table](/page/Symbol_table))

handle any runtime errors interactively

else:

report syntax or semantic error

while not end of program:

fetch next statement from AST

if statement is valid:

execute action (e.g., evaluate expression, update [symbol table](/page/Symbol_table))

handle any runtime errors interactively

else:

report syntax or semantic error

Intermediate Representations

Intermediate representations (IRs) in interpreters act as structured intermediaries between source code and direct execution, facilitating analysis, optimization, and evaluation while abstracting away low-level details of the host machine. These representations enable interpreters to process programs more efficiently than parsing source text on the fly, often by converting the code into a form that supports straightforward traversal or sequential dispatch. The Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) is a fundamental IR consisting of a hierarchical tree that captures the syntactic structure of the source code, with nodes representing constructs like expressions, statements, and operators, while stripping away tokens such as whitespace and delimiters. In tree-walking interpreters, execution proceeds by recursively traversing the AST, evaluating each node based on its type and children—for instance, computing the value of an expression node by evaluating its operands first. This representation preserves much of the original code's semantic hierarchy, making it intuitive for debugging and language implementation.[33][33] Bytecode serves as another prevalent IR, comprising a low-level, platform-independent sequence of opcodes and operands compiled from the source code to enable rapid interpretation via a virtual machine. Unlike source code, bytecode is compact and optimized for sequential execution, reducing parsing overhead during runtime; for example, Python compiles scripts to bytecode stored in .pyc files, where instructions like LOAD_CONST and BINARY_ADD handle operations efficiently. This form allows interpreters to achieve better performance by treating the program as a linear stream of simple, atomic actions rather than a complex structure. Alternative IRs include Polish notation (prefix notation), which linearizes expressions by placing operators before their operands, eliminating the need for parentheses and suiting stack-based evaluation in early interpreters through operator precedence hierarchies and stack manipulation. De Bruijn indices offer a name-free approach for handling variable bindings, particularly in functional or lambda-based languages, by representing variables as numeric indices referencing enclosing scopes in the environment, thus avoiding alpha-renaming issues during substitution.[34] Traditionally, ASTs provide conceptual clarity and fidelity to the source language but are assumed to suffer from execution slowdowns due to repeated traversals and indirect dispatch costs, whereas bytecode promotes speed and compactness at the expense of requiring a dedicated evaluator and potentially complicating source-level manipulations; however, recent studies indicate that AST interpreters can be performance-competitive with bytecode approaches in modern systems.[35][35] Consider the arithmetic expression2 + 3: in an AST, it forms a root addition node with child leaves for the integer literals 2 and 3, evaluated bottom-up during traversal; in bytecode, it translates to a sequence such as LOAD_CONST 2, LOAD_CONST 3, BINARY_ADD, processed linearly by the interpreter's dispatch loop.[33]

Advantages

Reduced Development Time

One key advantage of interpreters in software development is the elimination of the compilation phase, allowing code to execute immediately upon writing or modification. This immediate feedback reduces iteration cycles from potentially minutes or hours in compiled environments—where full recompilation is required—to mere seconds, enabling developers to test changes rapidly without intermediate build steps. As a result, prototyping and iterative refinement become significantly more efficient, particularly in dynamic environments where frequent adjustments are common.[36] Interpreted languages often incorporate built-in support for interactive debugging, further accelerating development by facilitating real-time inspection and modification of code. For instance, Python's pdb module provides breakpoints, step-through execution, and variable watching directly within the interpreter, while Ruby's built-in debugger (ruby -r debug) allows similar interactive sessions for hot-swapping code snippets during runtime. These features minimize the need for external tools or rebuilds, streamlining error identification and resolution compared to compiled languages that require recompilation after changes. In modern integrated development environments like Visual Studio Code, extensions such as the Python Extension Pack integrate REPL (Read-Eval-Print Loop) capabilities, enabling seamless switching between editing and execution to enhance workflow efficiency. This reduced development time makes interpreters particularly suited for use cases emphasizing speed of change, such as prototyping new features, writing scripts for automation, and agile software practices in web development. Studies and expert assessments indicate that interpreted languages like Python can yield 3-5 times faster development cycles compared to compiled languages like Java, and up to 5-10 times faster than low-level languages like C/C++, primarily due to shorter feedback loops and simpler syntax. For example, in web development scenarios involving rapid iteration, teams using Ruby on Rails report accelerated delivery of minimum viable products, underscoring the role of interpreters in fostering innovation without sacrificing initial momentum.[36]Portability and Distribution

One key advantage of interpreters in computing is their facilitation of platform independence. Unlike compiled languages, which require recompilation for each target architecture or operating system, interpreted source code can execute on any platform where a compatible interpreter is available, without modification or rebuilding. This portability stems from the interpreter abstracting machine-specific details, allowing the same code to run across diverse environments such as Windows, Linux, and macOS.[37][38] For instance, Python scripts operate seamlessly on multiple operating systems as long as the Python interpreter is installed, enabling developers to distribute code without platform-specific binaries. Distribution of interpreted software typically involves shipping the source code alongside the interpreter or embedding the interpreter within a larger application. In the former model, users receive lightweight scripts that the interpreter executes directly, as seen in Perl one-liners—concise programs run via command-line flags likeperl -e 'print "Hello, world\n"'—which require no compilation and can be shared as text files for immediate execution on any system with Perl installed.[39] Alternatively, embedding allows integration into host applications, where the interpreter acts as a runtime for scripting extensions; this approach is common in software plugins and avoids distributing full executables. Interpreters like Lua exemplify this, with its small footprint (under 300 KB) making it ideal for bundling into applications without significantly increasing distribution size.[29]

These models yield several benefits, including simplified updates and reduced binary sizes compared to compiled applications. Source code distribution enables easy patching or modification without recompilation, streamlining maintenance for open-source projects and collaborative environments.[40] Moreover, interpreted setups often result in smaller deployable artifacts, as scripts remain compact while the interpreter handles execution, which is particularly valuable for plugins and modular software. Lua's embeddability has made it a staple in game development, powering scripting in titles like World of Warcraft and Angry Birds, where it allows dynamic content updates without redistributing the entire game binary.[29] Although the need to include or ensure the interpreter's presence can sometimes inflate overall distribution packages, this trade-off supports broader accessibility.[38]

Challenges

Performance Considerations

Interpreters in computing introduce significant runtime performance overhead compared to compiled native executables, primarily stemming from the need to parse and translate source code or intermediate representations on each execution, without the benefits of ahead-of-time (AOT) optimizations that compilers apply statically. This process involves dynamically interpreting instructions through a dispatch loop, which incurs repeated evaluation costs not present in pre-optimized machine code. Additionally, the absence of AOT allows no opportunity for platform-specific code generation or aggressive optimizations like loop unrolling or dead code elimination prior to runtime, exacerbating slowdowns in compute-heavy scenarios.[41] Quantitative benchmarks illustrate these limitations, showing interpreters typically execute 5 to 50 times slower than native code for CPU-bound tasks, such as iterative loops or numerical computations. For instance, in Python workloads, the standard CPython interpreter demonstrates slowdowns of 2.4 to 119 times relative to optimized C++ equivalents across a range of empirical tests.[42] Even advanced interpreters like PyPy, which incorporate just-in-time elements but remain fundamentally interpretive in baseline operation, achieve only about 2.8 times the speed of CPython on average in 2020s benchmarks, still trailing native performance by a significant factor (typically 5-10x slower) in pure computational loops.[43] Recent developments, such as CPython's optimized evaluator in versions 3.11 and later (providing up to 50% speedup in select loops as of 2024) and experimental JIT in Python 3.14 (as of 2025), help mitigate some overheads in hybrid configurations.[44][45] To mitigate these overheads without resorting to full compilation, interpreters often employ basic caching mechanisms, such as storing parsed abstract syntax trees or bytecode in memory or on disk to bypass repeated parsing on subsequent invocations. Stack caching techniques, for example, further reduce dispatch costs by maintaining virtual machine state in registers, yielding measurable but limited improvements in execution time for certain workloads.[46] However, these strategies fall short of comprehensive optimization, preserving the inherent interpretive loop that prevents parity with native speeds. In practice, such performance penalties are often tolerable or negligible in I/O-bound applications, including web servers, where program execution primarily awaits network requests, database queries, or file operations rather than intensive CPU processing. Benchmarks of server-side scripts confirm that interpretive overhead contributes minimally here, as idle time during I/O dominates total latency.[47] These evaluations establish interpreters against native executables as the baseline, distinct from hybrid approaches that blend interpretation with dynamic compilation. Performance considerations in speed also tie into broader efficiency trade-offs, such as increased memory demands from runtime structures.Efficiency Trade-offs

Interpreters generally exhibit a higher memory footprint than compiled systems owing to the maintenance of runtime data structures, such as symbol tables, which store details on identifiers, scopes, and types to support dynamic resolution during execution.[35] In abstract syntax tree (AST) interpreters, this footprint is particularly pronounced due to the need to traverse and retain the parse tree in memory, contrasting with more compact bytecode representations that reduce storage demands.[35] For dynamic languages, garbage collection introduces additional overhead, as automatic memory reclamation processes consume CPU cycles and can pause execution, impacting overall throughput by tracking and recovering unused objects in the heap.[48] Resource trade-offs in interpreters often balance ease of concurrency against elevated CPU consumption in the core interpretation loop. Mechanisms like Python's Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) enable straightforward thread-based concurrency for I/O-bound tasks by serializing bytecode execution, but this simplicity incurs higher CPU overhead for the interpreter itself and limits true parallelism in CPU-intensive workloads.[49] In contrast, multiprocess approaches bypass such locks to achieve parallelism but introduce inter-process communication costs and increased memory usage per process.[50] Design choices in interpreters frequently prioritize simplicity to facilitate rapid prototyping and portability, yet this can lead to scalability limitations for large-scale applications where unoptimized structures hinder efficient resource allocation. For instance, favoring flexible runtime environments over aggressive ahead-of-time optimizations trades development ease for potential bottlenecks in handling extensive codebases or high-load scenarios.[51] In practice, interpreters prove efficient for short-lived scripts, where the absence of compilation overhead allows quick startup and execution without amortizing long-term costs. However, for long-running server applications, the persistent interpretation loop results in sustained resource inefficiency, making them less suitable without supplementary enhancements.[49] Security features like sandboxing further compound these trade-offs, imposing efficiency costs—such as 2% to 60% slowdowns depending on architecture and workload—to isolate untrusted code and prevent unauthorized resource access in dynamic runtimes.[52]Implementation Methods

Tree-Walking Interpreters

Tree-walking interpreters execute programs by first parsing the source code into an abstract syntax tree (AST) that captures the program's syntactic structure. During evaluation, the interpreter recursively traverses the AST in a depth-first manner, visiting each node and computing its value based on the node's type and its children. For example, when processing an expression tree, the interpreter evaluates subexpressions by descending into child nodes and then combines the results according to the operator at the parent node. This direct evaluation mirrors the program's structure closely, allowing the interpreter to compute results without generating intermediate code.[53] The primary advantages of tree-walking interpreters lie in their simplicity and ease of development. Implementation is straightforward since the evaluation logic aligns directly with the AST nodes, making it easier to debug and extend compared to more complex systems. Additionally, no separate virtual machine or bytecode dispatcher is required, reducing the overall codebase size and complexity.[53] Despite these benefits, tree-walking interpreters suffer from significant performance overhead due to the repeated traversal of the tree, which involves numerous function calls, object accesses, and recursive invocations for each node. This can result in slower execution speeds, particularly for larger programs, as the interpreter must navigate the hierarchical structure multiple times during runtime. In contrast to bytecode interpreters, which use a linear sequence of instructions for more efficient dispatch, tree-walking approaches incur higher interpretive costs from structural navigation.[54][55] Examples of tree-walking interpreters include the QLogo implementation for the Logo programming language, where execution traverses AST nodes to perform actions like drawing commands and procedure calls. Similarly, simple JavaScript expression evaluators often employ this method to compute mathematical expressions by walking parsed trees.[56][57] A typical pseudocode snippet for evaluating a binary operation node illustrates the recursive nature:def evaluate(node, environment):

if node.type == "BinaryOp":

left_value = evaluate(node.left, environment)

right_value = evaluate(node.right, environment)

if node.operator == "+":

return left_value + right_value

elif node.operator == "-":

return left_value - right_value

# Handle other operators similarly

# Handle other node types (e.g., literals, variables)

elif node.type == "Number":

return node.value

# etc.

def evaluate(node, environment):

if node.type == "BinaryOp":

left_value = evaluate(node.left, environment)

right_value = evaluate(node.right, environment)

if node.operator == "+":

return left_value + right_value

elif node.operator == "-":

return left_value - right_value

# Handle other operators similarly

# Handle other node types (e.g., literals, variables)

elif node.type == "Number":

return node.value

# etc.

Bytecode Interpreters

Bytecode interpreters represent a key approach in program execution where source code is first translated into an intermediate bytecode representation, which is then processed by a virtual machine (VM). This method involves compiling the high-level source code into a sequence of bytecode instructions, consisting of opcodes (operation codes) that specify actions and operands that provide necessary data or references. The VM then executes this bytecode in a controlled loop, dispatching each instruction sequentially to perform operations such as arithmetic, control flow, or memory access. This separation of compilation and execution enhances both portability—allowing the bytecode to run on any compatible VM—and maintainability, as the VM can be optimized independently of the source language. Central to bytecode interpreters are core components like the opcode table, which maps each opcode to its corresponding execution routine, and a stack-based machine model that handles operand evaluation and temporary storage. In a typical stack machine, operands are pushed onto an evaluation stack before operations pop them for processing, with results pushed back if needed; this avoids the need for explicit register allocation in the bytecode. For instance, an addition operation might be encoded as a single opcode that pops two values, adds them, and pushes the result, promoting a compact and uniform instruction set. Such designs draw from early virtual machine concepts, enabling efficient simulation of hardware-like behavior in software. Compared to tree-walking interpreters, which traverse abstract syntax trees recursively, bytecode interpreters achieve superior performance through linear instruction dispatch, reducing overhead from repeated tree navigation. The bytecode's compact form also facilitates smaller program sizes and easier distribution, as it abstracts away platform-specific details while remaining more efficient than pure source interpretation. These advantages have made bytecode VMs foundational in languages prioritizing ease of implementation and cross-platform compatibility. Prominent examples include the CPython virtual machine, which interprets Python bytecode generated by its compiler, handling tasks like object manipulation and exception handling via a threaded dispatch loop. Similarly, Lua's virtual machine executes bytecode in a register-based model, optimizing for embedding in applications with its lightweight design. These systems illustrate how bytecode interpreters balance interpretative flexibility with near-native speeds in constrained environments. Dispatch mechanisms in bytecode interpreters vary for performance tuning, with switch-based dispatching using a large switch statement to route opcodes to handlers, offering simplicity but potential branch prediction costs on modern CPUs. An alternative, computed goto dispatching—leveraging compiler extensions like GCC's labels-as-values—creates a direct jump table, eliminating switch overhead and improving execution speed by up to 20-30% in benchmarks.[58] These methods underscore ongoing optimizations in VM design. The evolution of bytecode interpreters traces back to systems like the UCSD Pascal p-System in the 1970s, which popularized portable bytecode execution, influencing modern VMs such as those in Java and .NET. This lineage addresses early limitations in pure interpretation by providing a structured, machine-independent layer that supports advanced features like garbage collection and security sandboxes, forming the backbone of countless runtime environments today.Advanced Techniques

Just-in-Time Compilation

Just-in-Time (JIT) compilation enhances interpreter performance by dynamically translating frequently executed code into native machine code during program execution. The process begins with an initial interpretation phase, where the runtime profiles execution to identify "hot" code paths—such as loops or functions invoked repeatedly—based on metrics like invocation counts and execution time. Once a threshold is met, the JIT compiler generates optimized machine code tailored to observed runtime behaviors, including type specializations and branch predictions, before caching it for reuse. This on-the-fly compilation bridges the gap between slow interpretation and static compilation by leveraging runtime information unavailable at build time.[59][60] Key algorithms in JIT compilation include method-based (or basic block) JIT, which compiles individual functions or methods independently, and tracing JIT, which records linear sequences of operations along dominant execution paths for more holistic optimizations. Tracing JIT proves especially advantageous for dynamic languages with variable control flow and types, as it captures actual usage patterns to eliminate overhead from rare branches or type checks. In contrast, method-based approaches suit structured code but may require additional inlining for peak efficiency. These techniques often employ intermediate representations, like sea-of-nodes graphs, to facilitate advanced optimizations such as common subexpression elimination.[61][62] The primary benefits of JIT compilation lie in achieving near-native execution speeds after a warmup period, while retaining interpretation's advantages in portability and dynamic adaptability. For long-running applications, this hybrid model can yield speedups of 2-10x over pure interpretation by reducing per-instruction overhead, with optimizations informed by real-world data leading to more precise code generation than ahead-of-time methods.[63][64] Prominent examples include the V8 JavaScript engine in Google Chrome, which uses the Ignition interpreter to generate bytecode and profile hot functions, then applies TurboFan for advanced JIT compilation into optimized machine code; this pipeline enables JavaScript to rival compiled languages in benchmarks. LuaJIT, a tracing-based JIT for the Lua language, compiles hot traces on-the-fly, often outperforming other dynamic language runtimes in numerical and string-processing tasks due to its aggressive optimizations.[60][62][64] In the 2020s, JIT advancements have focused on reducing latency in hybrid systems, such as V8's Maglev compiler introduced in 2023, which serves as a fast baseline JIT to accelerate warmup by compiling simpler optimizations 10x faster than full-tier compilers while approaching their peak throughput. For WebAssembly, runtimes like those in modern browsers employ tiered JIT strategies combining interpretation, baseline compilation, and optimizing JIT to handle diverse modules efficiently, supporting applications from games to compute-intensive tasks with minimal overhead. A notable 2024 development is Python 3.13's experimental JIT compiler, which aims to improve performance in the CPython implementation, though it may sometimes underperform the interpreter in certain scenarios.[62][65] Despite these gains, JIT compilation incurs trade-offs, including startup slowdowns from profiling and code generation—potentially doubling initial execution time—and elevated memory consumption for storing profiles, caches, and multiple code versions to handle deoptimization when assumptions fail. These costs are mitigated in production runtimes through techniques like tiered compilation, but they remain critical considerations for short-lived or memory-constrained environments.[59][66]Partial Evaluation

Partial evaluation is a program transformation technique that specializes a program by evaluating it with respect to a subset of its inputs known at "compile" time, thereby generating optimized residual code for the remaining unknown inputs. This process applies known static values to simplify computations, such as unfolding loops with constant bounds or inlining functions with fixed parameters, resulting in more efficient executable code. In the domain of interpreters, partial evaluation treats the interpreter itself as the subject program, specializing it to produce tailored code that executes faster by eliminating interpretive overhead for static elements.[67] The process typically involves two main stages: binding-time analysis followed by the partial evaluation itself. Binding-time analysis classifies program variables and computations as static (known at specialization time) or dynamic (unknown until runtime), often using flow analysis to propagate binding-time information and ensure safe specialization without runtime errors. Once classified, the partial evaluator performs a form of "mixed" execution: it fully computes static parts and copies or symbolically represents dynamic parts into the residual code, which may be a specialized interpreter or directly executable program. This approach is particularly effective for generating optimized code from high-level interpreters.[68] A seminal application of partial evaluation in interpreters is illustrated by the Futamura projections, which demonstrate how it can automate compiler generation. The first projection specializes an interpreter with respect to a fixed source program to yield a dedicated compiler for that program; the second specializes the resulting compiler with respect to another source program to produce a compiler generator; and the third applies partial evaluation to the compiler generator itself to create a self-applicable compiler generator. These projections, first proposed in 1971, highlight partial evaluation's potential to derive compilation tools directly from interpreters without manual coding.[69] Partial evaluation finds applications in domain-specific languages (DSLs), where interpreters for specialized domains can be specialized ahead-of-time to produce efficient, low-level code tailored to particular problem instances, and in optimizing interpreters for general-purpose languages by reducing abstraction layers. For instance, in embedded DSLs, partial evaluation of the host-language interpreter with respect to DSL constructs generates performant code integrated with the host environment. It is also used to enhance the efficiency of meta-programming systems by specializing interpreters for recurring tasks.[70] Despite its power, partial evaluation has limitations: it excels with programs having significant static structure but struggles with highly dynamic code, where extensive binding-time analysis may fail to identify specializable parts, leading to residual code that retains much of the original overhead. Complex control flows or side effects can also complicate the process, requiring annotations or restrictions to ensure termination and correctness. As a result, partial evaluation remains a niche technique in research and specialized systems, less prevalent than runtime methods like just-in-time compilation, though it provides foundational insights into program specialization.[71]Variations and Types

Pure Interpreters

A pure interpreter executes source code directly through parsing and evaluation of its abstract syntax tree (AST), without any intermediate compilation phase to generate bytecode or machine code. This approach maps source constructs immediately to actions, simulating the language's semantics in a straightforward loop: fetching the next statement, determining the required operations, and invoking routines to perform them.[72][73] Unlike more optimized variants, pure interpreters avoid any form of code generation, relying solely on runtime traversal of the parsed structure to drive execution. This direct-execution model offers the highest flexibility for supporting dynamic language features, such as theeval() function, which requires on-the-fly parsing and immediate execution of dynamically generated code strings. By maintaining the full AST during runtime, pure interpreters enable seamless introspection and modification of program structures without the constraints of pre-compiled representations. Early JavaScript engines, for instance, employed parse tree evaluators—essentially pure interpreters—to handle such dynamic behaviors in web scripting environments.[74]

Pure interpreters find use in educational tools, where their simplicity aids in teaching language semantics, as seen in implementations for Lisp dialects that execute source on the fly. They are also suited for embedded scripting in resource-constrained settings, such as microcontrollers, owing to their compact footprint and lack of additional compilation artifacts, making them preferable over bytecode systems in memory-limited devices.[72]

However, pure interpreters incur maximal performance overhead due to repeated AST traversals and indirect dispatch for each operation, resulting in slower execution compared to alternatives. In contrast, bytecode interpreters mitigate this by introducing a preliminary compilation step to a compact intermediate form, enabling faster linear scanning and reduced per-instruction costs. Despite these drawbacks, pure interpreters persist in low-resource environments where simplicity and minimal memory usage outweigh speed concerns. Hybrid systems have evolved from this base model to incorporate optimizations while retaining core direct-execution benefits.

Hybrid Systems

Hybrid systems in computing interpreters integrate elements of both interpretation and compilation to dynamically adapt execution strategies based on runtime conditions. These systems typically interpret infrequently executed or "cold" code to ensure rapid startup and low initial memory usage, while compiling frequently accessed "hot" paths to native machine code for improved performance. This approach, often realized through just-in-time (JIT) compilation triggered by usage patterns, allows virtual machines to balance the trade-offs inherent in pure interpretation or full compilation.[75] The Java HotSpot Virtual Machine employs a bytecode interpreter for initial execution, profiling methods to identify hot spots, and then invokes its C1 and C2 JIT compilers for optimization, achieving up to several times faster execution on repeated paths. Benefits include minimized startup latency compared to pure compilers, reduced memory footprint relative to always-interpreted code, and peak performance approaching native speeds for long-running applications.[75] Examples of hybrid systems extend to polyglot environments like GraalVM, which supports multiple languages through Truffle-based interpreters that are automatically optimized by its JIT compiler, enabling seamless interoperability and high performance across languages such as Java, JavaScript, and Python. PyPy's implementation, built on RPython, uses a tracing JIT that records interpreter execution traces for hot loops, compiling them to machine code while interpreting the rest, resulting in significant speedups for dynamic workloads like numerical computations. Decision heuristics in these systems often involve sampling-based profiling, such as method invocation counters in HotSpot, or tracing loops in PyPy to detect and prioritize compilation candidates, ensuring compilation overhead is justified by anticipated gains.[76][77][78] In modern virtual machines as of 2024, hybrid systems have become the dominant paradigm, powering runtimes like the JVM and V8, with ongoing advancements in polyglot support and automated AOT-JIT hybridization to address diverse application needs in cloud and AI-driven environments. This versatility contrasts with pure interpreters by incorporating compiler elements for adaptability, though at the cost of increased implementation complexity.[79]Examples in Practice

Language-Specific Interpreters

Language-specific interpreters are designed with unique architectural choices that reflect the priorities and ecosystems of their respective programming languages, such as emphasizing ease of use, performance in dynamic environments, or developer productivity. These interpreters often incorporate specialized virtual machines (VMs), garbage collection mechanisms, and concurrency models to handle language-specific semantics efficiently. Examples like CPython for Python, V8 for JavaScript, and MRI for Ruby illustrate how interpreters adapt to diverse needs, from data processing to web interactivity. CPython, the reference implementation of Python, operates as a bytecode virtual machine that compiles source code into platform-independent bytecode, which is then executed by the Python Virtual Machine (PVM). It employs a Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) to manage threading, ensuring thread safety in the presence of Python's reference counting garbage collection, though this limits true parallelism in multi-threaded CPU-bound tasks. CPython prioritizes code readability and extensibility through a rich standard library and support for C extensions via the Python/C API, allowing seamless integration of performance-critical code written in C. For concurrency, it supports multiprocessing and asynchronous programming via the asyncio module, while error recovery is handled through exception hierarchies that propagate up the call stack with detailed tracebacks. A simple "Hello World" program in Python,print("Hello World"), is parsed into bytecode operations like LOAD_GLOBAL for 'print', LOAD_CONST for the string, and CALL_FUNCTION, executed sequentially by the VM to output the message without additional overhead.

V8, the JavaScript engine developed by Google for Chrome and Node.js, is predominantly just-in-time (JIT) compilation-based but includes an interpreter for initial code warmup and deoptimization scenarios. It excels in web performance by optimizing dynamic code through techniques like hidden classes for object prototypes and inline caching for property access, handling JavaScript's prototype-based inheritance efficiently. V8 manages concurrency via an event loop that processes asynchronous callbacks, enabling non-blocking I/O in browser and server environments, while error recovery involves try-catch blocks that unwind the stack and resume execution. Extensions are supported through C++ APIs for embedding V8 in applications, such as in Node.js addons. For a "Hello World" script, console.log("Hello World");, V8's Ignition interpreter first parses it into bytecodes for loading the console object, retrieving the log method, and invoking it with the string constant, potentially handing off to TurboFan for JIT optimization on repeated executions.

Matz's Ruby Interpreter (MRI), also known as YARV (Yet Another Ruby VM), is a bytecode interpreter that compiles Ruby source code to YARV bytecode after parsing it into an abstract syntax tree (AST), and then executes the bytecode using a stack-based virtual machine. It features a mark-and-sweep garbage collector to manage memory for Ruby's object-oriented, dynamically typed objects, emphasizing developer happiness through concise syntax and metaprogramming capabilities. Concurrency in MRI is constrained by its own GIL-like mechanism, favoring green threads and libraries like fibers for cooperative multitasking, with error recovery via rescue blocks that catch exceptions and allow graceful handling. Ruby supports extensions through C APIs, enabling FFI for integrating native libraries to boost performance in I/O-heavy tasks. In executing puts "Hello World", MRI executes the bytecode instructions corresponding to the puts method call on the string literal, invoking the IO.puts kernel method to print the output, with garbage collection pausing briefly if needed during object allocation.

These interpreters highlight tailored trade-offs: CPython's bytecode VM suits Python's dominance in data science due to its extensive libraries and straightforward extension model, while V8's JIT focus powers client-side JavaScript for responsive web applications. In contrast, MRI's bytecode design aligns with Ruby's emphasis on expressive code, though it may yield different performance profiles in concurrent scenarios.