Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

IBM 700/7000 series

View on Wikipedia

| |

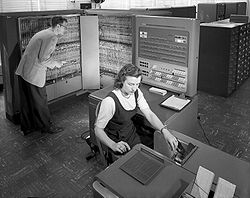

An IBM 704 mainframe at NACA in 1957 | |

| Type | Mainframe/ scientific computer |

|---|---|

| Release date | 1953 |

| Successor | IBM 8000 (not released) IBM System/360 |

| Related | IBM 1400 series |

| History of IBM mainframes, 1952–present |

|---|

| Market name |

| Architecture |

The IBM 700/7000 series is a series of large-scale (mainframe) computer systems that were made by IBM through the 1950s and early 1960s. The series includes several different, incompatible processor architectures. The 700s use vacuum-tube logic and were made obsolete by the introduction of the transistorized 7000s. The 7000s, in turn, were eventually replaced with System/360, which was announced in 1964. However the 360/65, the first 360 powerful enough to replace 7000s, did not become available until November 1965. Early problems with OS/360 and the high cost of converting software kept many 7000s in service for years afterward.

Architectures

[edit]The IBM 700/7000 series has six completely different ways of storing data and instructions:

- First scientific (36/18-bit words): 701 (Defense Calculator)

- Later scientific (36-bit words, hardware floating-point): 704, 709, 7040, 7044, 7090, 7094

- Commercial (variable-length character strings): 702, 705, 7080

- 1400 series (variable-length character strings): 7010

- Decimal (10-digit words, hardware floating-point): 7070, 7072, 7074

- Supercomputer (64-bit words, hardware floating-point): 7030 "Stretch"

The 700 class machines use vacuum tubes; the 7000 class machines are transistorized. All machines (like most other computers of the time) use magnetic-core memory; except for early 701 and 702 models, which initially used Williams tube CRT memory and were later converted to magnetic-core memory.

Software compatibility issues

[edit]Early computers were sold without software. As operating systems began to emerge, having four different mainframe architectures plus the IBM 1400 midline architectures became a major problem for IBM since it meant at least four different programming efforts were required.

The System/360 combines the best features of the 7000 and 1400 series architectures into a single design both for commercial computing and for scientific and engineering computing. However, its architecture is not compatible with those of the 7000 and 1400 series, so some 360 models have optional features that allow them to emulate the 1400 and 7000 instruction sets in microcode. One of the selling points of the System/370, the successor of the 360 introduced in mid-1970, was improved 1400/7000 series emulation, which could be done under operating system control rather than shutting down and restarting in emulation mode as was required for emulation of 7040/44, 7070/72/74, 7080 and 7090/94 on all of the 360s except the 360/85.

Peripherals

[edit]While the architectures differ, the machines in the same class use the same electronics technologies and generally use the same peripherals. Tape drives generally[a] use 7-track format, with the IBM 727 for vacuum tube machines and the 729 for transistor machines. Both the vacuum tube and most transistor models use the same card readers, card punches, and line printers that were introduced with the 701. These units, the IBM 711, 721, and 716, are based on IBM accounting machine technology and even include plugboard control panels. They are relatively slow and it was common for 7000 series installations to include an IBM 1401, with its much faster peripherals, to do card-to-tape and tape-to-line-printer operations off-line. Three later machines, the 7010, the 7040 and the 7044, adopted peripherals from the midline IBM 1400 series. Some of the technology for the 7030 was used in data channels and peripheral devices on other 7000 series computers, e.g., 7340 Hypertape.

First scientific architecture (701)

[edit]

Known as the Defense Calculator while in development in the IBM Poughkeepsie Laboratory, this machine was formally unveiled April 7, 1953 as the IBM 701 Electronic Data Processing Machine.

- Data formats

Numbers are either 36 bits or 18 bits long, only fixed point.

- Fixed-point numbers are stored in binary sign/magnitude format.

- Instruction format

Instructions are 18 bits long, single address.

- Sign (1 bit) – Whole-word (-) or Half-word (+) operand address

- Opcode (5 bits) – 32 instructions

- Address (12 bits) – 4096 Half-word addresses

To expand the memory from 2048 to 4096 words, a 33rd instruction was added that uses the most-significant bit of its address field to select the bank. (This instruction was probably created using the "No OP" instruction, which appears to have been the only instruction with unused bits, as it originally ignored its address field. However, documentation on this new instruction is not currently available.)

- Registers

Processor registers consisted of:

- AC – 38-bit Accumulator

- MQ – 36-bit Multiplier-Quotient

- Memory

2,048 or 4,096 – 36-bit binary words with six-bit characters

Later scientific architecture (704/709/7090/7094)

[edit]

IBM's 36-bit scientific architecture was used for a variety of computation-intensive applications. First machines were the vacuum-tube 704 and 709, followed by the transistorized 7090, 7094, 7094-II, and the lower-cost 7040 and 7044. The ultimate model was the Direct Coupled System (DCS) consisting of a 7094 linked to a 7044 that handled input and output operations.

- Data formats

Numbers are 36 bits long, for both fixed-point arithmetic and floating-point arithmetic.

- Fixed-point numbers are stored in binary sign/magnitude format.

- Single-precision floating-point numbers have a magnitude sign, an 8-bit excess-128 exponent and a 27-bit magnitude

- Double-precision floating-point numbers, introduced on the 7094, have a magnitude sign, a 17-bit excess-65536 exponent, and a 54-bit magnitude

- Alphameric characters are 6-bit BCD, packed six to a word.

- Instruction format

The basic instruction format is a three-bit prefix, fifteen-bit decrement, three-bit tag, and fifteen-bit address. The prefix field specifies the class of instruction. The decrement field often contains an immediate operand to modify the results of the operation, or is used to further define the instruction type. The three bits of the tag specify three (seven in the 7094) index registers, the contents of which are subtracted from the address to produce an effective address. The address field either contains an address or an immediate operand.

- Registers

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Processor registers consisted of:

- AC – 38-bit Accumulator

- MQ – 36-bit Multiplier-Quotient

- XR – 15-bit Index Registers (three or seven)

- SI – 36-bit Sense Indicator

The accumulator (and multiplier-quotient) registers operate in sign/magnitude format. The accumulator has two overflow bits, labelled Q and P. Logical instructions clear or ignore S and Q; the Add and Carry Logical (ACL) instruction does an end-around carry from bit P to bit 35.

The Index registers operate using two's complement format and when used to modify an instruction address are subtracted from the address in the instruction. On machines with three index registers, if the tag has two or three bits set (i.e. selected multiple registers) then their values are ORed together before being subtracted. The IBM 7094, with seven index registers, powers up in multiple tag mode for compatibility with earlier machines, so that programs that used this trick could continue to be used; the Leave Multiple Tag Mode (LMTM) instruction turns that mode off, so that the tag specifies which of the index registers to use, and the Enter Multiple Tag Mode (EMTM) instruction turns it back on.

The Sense Indicators permit interaction with the operator via panel switches and lights.

- Memory

- 704: 4,096 or 8,192 or 32,768 – 36-bit binary words with six-bit characters

- 709, 7090, 7094, 7094 II, 7040, 7044: 32,768 – 36-bit binary words with six-bit characters

- Input/output

The 709/7090 series use Data Synchronizer Channels for high-speed input/output, such as tape and disk. The basic 7-bit[b] DSCs, e.g., 7607, execute their own simple programs from the computer memory that controls the transfer of data between memory and the I/O devices; the more advanced 9-bit[c] 7909 supports more sophisticated channel programs. Because the unit record equipment on the 709x was so slow, punched card I/O and high-speed printing were often performed by transferring magnetic tapes to and from an off-line IBM 1401. Later, the data channels were used to connect a 7090 to a 7040 or a 7094 to a 7044 to form the IBM 7094/7044 Direct Coupled System (DCS). In that configuration, the 7044, which could use faster 1400 series peripherals, primarily handled I/O.

FORTRAN assembly program

[edit]The FORTRAN Assembly Program (FAP) is an assembler for the 709, 7090, and 7094, originally written at the Western Data Processing Center by David E. Ferguson and Donald P. Moore for the 709.[1] It runs under IBM's Fortran Monitor System (FMS) and IBSYS operating systems. An earlier assembler was SHARE Compiler-Assembler-Translator (SCAT) under SHARE Operating System (SOS). Macros were added to FAP by Bell Laboratories (BE-FAP), and the final 7090/7094 assembler was Macro Assembly Program (IBMAP), under IBSYS/IBJOB. SCAT, FAP and MAP were mutually incompatible.

Its pseudo-operation BSS, used to reserve memory, is the origin of the common name of the "BSS section", still used in many assembly languages today for designating reserved memory address ranges of the type not having to be saved in the executable image.

Commercial architecture (702/705/7080)

[edit]

The IBM 702 and IBM 705 are similar, and the 705 can run many 702 programs without modification, but they are not completely compatible.

The IBM 7080 is a transistorized version of the 705, with various improvements. For backward compatibility it can be run in 705 I[2] mode, 705 II[3] mode, 705 III[4] mode, or full 7080 mode.

- Data format

Data is represented by a variable-length string of characters terminated by a Record mark.

- Instruction format

Five characters: one character opcode and four character address – OAAAA

- Registers

- 702

- two Accumulators (A & B) – 512 characters

- 705

- one Accumulator – 256 characters

- 14 auxiliary storage units – 16 characters

- one auxiliary storage unit – 32 characters

- 7080

- one Accumulator – 256 characters

- 30 auxiliary storage units – 512 characters

- 32 communication storage units – 8 characters

- Memory

- 702

- 2,000 to 10,000 characters in Williams tubes (in increments of 2,000 characters)

- Character cycle rate – 23 microseconds

- 705 (models I, II, or III)

- 20,000 or 40,000 or 80,000 characters of core memory

- Character cycle rate – 17 microseconds or 9.8 microseconds

- 7080

- 80,000 or 160,000 characters of Core memory

- Character cycle rate – 2.18 microseconds

- Input/output

The 705 and the basic 7080 use channels with a 7-bit[b] interface. The 7080 can be equipped with 7908 data channels to attach faster devices using a 9-bit[c] interface.

1400 series architecture (7010)

[edit]

The 700/7000 commercial architecture inspired the very successful IBM 1400 series of mid-sized business computers. In turn, IBM later introduced a mainframe version of the IBM 1410 called the IBM 7010.

- Data format

- Data is represented by a variable length string of characters terminated by a word mark.

- Instruction format

- Variable length: 1, 2, 6, 7, 11, or 12 characters.

- Registers

Fifteen five-character fields in fixed locations in low memory can be treated as index registers, whose values can be added to the address specified in an instruction. Also, certain internal registers that would today be invisible, such as the addresses of the characters being currently processed, are exposed to the programmer; in particular, the B address register is often used for subroutine linkage.

- Memory

- 100,000 characters[5]

Decimal architecture (7070/7072/7074)

[edit]

The IBM 7070, IBM 7072, and IBM 7074 are decimal, fixed-word-length machines. They use a ten-digit word like the smaller and older IBM 650, but are not instruction set compatible with the 650.

- Data format

- Word length – 10 decimal digits plus sign

- Digit encoding – two-out-of-five code

- Floating point – optional, with a two-digit exponent

- Three signs for each word – Plus, Minus, and Alpha

- Plus and Minus indicate 10-digit numeric values

- Alpha indicates five characters of text coded by pairs of digits. 61 = A, 91 = 1.

- Instruction format

- All instructions use one word

- Two-digit opcode (including sign, Plus or Minus only)

- Two-digit index register

- Two-digit field control – allows selecting sets of digits, shifting left or right

- Four-digit address

- Registers

- All registers use one word and can also be addressed as memory.

- Accumulators – three (addresses 9991, 9992, and 9993 – standard; 99991, 99992, and 99993 – extended 7074)

- Program register – one (address 9995 – standard; 99995 – extended 7074)

- Addressable from console only. Stores current instruction.

- Instruction counter – one (address 9999 – standard; 99999 – extended 7074)

- Addressable from console only

- Index registers – 99 (addresses 0001-0099)

- Memory

- 5000 to 9990 words (standard)

- 15000 to 30000 words (extended 7074)

- Access time – 6 microseconds (7070/7072), 4 microseconds (7074)

- Add time – 72 microseconds (7070), 12 microseconds (7072), 10 microseconds (7074)

- Input/output

The 707x uses channels with a 7-bit[b] interface. The 7070 and 7074 can be equipped with 7907 data channels to attach faster devices using a 9-bit[c] interface.

Timeline

[edit]| year | category | logic | memory | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| decimal | commercial | scientific | supercomputer | |||

| 1952 | IBM 701[6] | vacuum tubes | Williams tubes | |||

| 1953 | IBM 702[6] | |||||

| 1954 | IBM 705 | IBM 704 | core memory | |||

| 1958 | IBM 709 | |||||

| IBM 7070 | transistors | |||||

| 1959 | IBM 7090 | |||||

| 1960 | IBM 7074 | |||||

| 1961 | IBM 7072 | IBM 7080 | IBM 7030 | |||

| 1962 | IBM 7010 | IBM 7094 | ||||

| 1963 | IBM 7040 IBM 7044 |

|||||

| 1964 | IBM 7094 II | |||||

An IBM 7074 was used by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service in 1962.[7]

The IBM 7700 Data Acquisition System is not a member of the IBM 7000 series, despite its number and its announcement date of December 2, 1963.

Performance

[edit]All of the 700 and 7000 series machines predate standard performance measurement tools such as the Whetstone (1972), Dhrystone (1984), LINPACK (1979), or Livermore loops (1986) benchmarks.

In the table below, the Gibson and Knight measurements report speed, where higher numbers are better; the TRIDIA measurement reports time, where lower numbers are better.

| Model | Gibson mix KIPS |

Knight Index scientific[8] |

TRIDIA program (FORTRAN) (seconds)[9] |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM 705 m1,2 | 0.50 | ||

| IBM 705 m3 | 0.38 | ||

| IBM 709 | 21 | ||

| IBM 7030 | 372 | 15.58 | |

| IBM 7040 | 148 | ||

| IBM 7044 | 109 | 74 | |

| IBM 7090 | 139 | 66 | |

| IBM 7094 | 176 | 31.35 | |

| IBM 7094 II | 257 | 217 | 16.50 |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ FORTRAN ASSEMBLY PROGRAM (FAP) for the IBM 709/7090 (PDF). 709/7090 Data Processing System Bulletin. IBM. 1961. J28-6098-1.

- ^ Weik, Martin H. (December 1955). "IBM-705". ed-thelen.org. A Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems.

- ^ Weik, Martin H. (March 1961). "IBM 705 I II". ed-thelen.org. A Third Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems.

- ^ Weik, Martin H. (March 1961). "IBM 705 III". ed-thelen.org. A Third Survey of Domestic Electronic Digital Computing Systems.

- ^ IBM-7010

- ^ a b "IBM highlights, 1885-1969" (PDF). IBM. December 2001. pp. 18–21. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 5, 2021.

- ^ Gannon, Robert (March 1963). "Big-Brother 7074 is watching you". Popular Science. Archived from the original on January 19, 2020. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- ^ M. Phister, Jr., Data Processing Technology and Economics, 2nd ed., 1979; Table II.2.11.1

- ^ Final Report on 64/6600 FORTRAN Version 3.0 (PDF) (Report). Control Data Corporation. June 6, 1966. section I.B, pp. 3-4.

External links

[edit]- IBM Mainframe family tree Archived January 14, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- The Architecture of IBM's Early Computers (PDF)

- C Gordon Bell, Computer Structures: Readings and Examples, McGraw-Hill, 1971; part 6, section 1, "The IBM 701-7094 II Sequence, a Family by Evolution", ISBN 0-07-004357-4

- IBM 705

- IBM 7030 Stretch

- IBM 7070

- IBM 7094

- IBM 7090/94 Architecture Archived May 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Jack Harper's FAP page Archived February 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Birth of an Unwanted IBM Computer, by Bob Bemer

- IBM 700 film

Reference manuals

[edit]- 701

- Principles of Operation - Type 701 and Associated Equipment (PDF). IBM. 1953. 24-6042-1. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 702

- IBM Electronic Data-Processing Machines - Type 702 (PDF). IBM. 1954. 22-6173-1. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 704

- 704 electronic data-processing machine - manual of operation (PDF). IBM. 1955. 24-6661-2. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 705

- Reference Manual - 705 Data Processing System (PDF). IBM. May 1959. A22-6506-0. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 7010

- IBM 7010 Principles of Operation (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library. IBM. A22-6726. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 7030

- Reference Manual - 7030 Data Processing System (PDF). IBM. August 1961. A22-6530-2. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 7040/7044

- IBM 7040-7044 Principles of Operation (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library. IBM. May 1964. A22-6640-4. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 7070/7072/7074

- Reference Manual - 7070 Data Processing System (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library. IBM. 1962. A22-7003-6. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 7080

- IBM 7080 Principles of Operation (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library. IBM. November 1964. A22-6560-4. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- 7090/7094

- Reference Manual - IBM 7090 Data Processing System (PDF). IBM. March 1962. A22-6528-4. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

- IBM 7094 Principles of Operation (PDF). IBM Systems Reference Library. IBM. 1966. A22-6703-4. Retrieved August 29, 2025.

IBM 700/7000 series

View on GrokipediaBackground and Development

Historical Context

Following World War II, the demand for high-speed computing surged due to military and scientific applications, particularly in ballistics calculations and complex numerical simulations that manual or electromechanical methods could no longer handle efficiently.[5] The U.S. military, seeking to process vast amounts of data for defense purposes, recognized the need for electronic computers to perform rapid arithmetic operations, as evidenced by wartime projects that accelerated technological innovation in this area.[6] These requirements extended beyond immediate postwar demobilization into ongoing national security efforts, driving investment in machines capable of handling iterative computations at unprecedented speeds.[7] The emergence of vacuum-tube technology marked a pivotal advancement in electronic computing, exemplified by the ENIAC, completed in 1945 as the first general-purpose programmable digital computer, which relied on over 17,000 vacuum tubes for its operations.[8] However, this technology faced significant limitations, including frequent tube failures that reduced reliability—ENIAC often required hours of maintenance for tube replacements—and high operational costs due to the expense and power consumption of the tubes themselves.[9] Similarly, the UNIVAC I, delivered in 1951 as the first commercial electronic computer, utilized around 5,000 vacuum tubes but suffered from similar issues, such as excessive downtime from tube malfunctions and substantial energy demands that limited its practicality for widespread use.[10] These constraints highlighted the nascent stage of electronic computing, where reliability and cost remained barriers to broader adoption despite the speed advantages over prior mechanical systems.[11] IBM, long established in punched-card tabulating equipment for data processing since the late 19th century, began transitioning toward electronic stored-program computers in the early 1950s to meet evolving market demands.[12] This shift was formalized in 1952 when IBM decided to enter the scientific computing market, moving beyond its traditional electromechanical tabulators to develop machines that could store and execute programs electronically, thereby addressing the growing need for computational power in research and engineering.[13] A key catalyst was the U.S. Air Force contract awarded to IBM in the early 1950s for what became the 701 Defense Calculator, representing the company's inaugural major venture into defense-oriented electronic computing and securing initial production commitments.[14] This series of developments positioned the 700/7000 line as a critical bridge to IBM's later unified architecture in the System/360 family.[1]Series Overview

The IBM 700/7000 series comprised IBM's initial family of large-scale mainframe computers, marking the company's entry into electronic data processing from the early 1950s through the mid-1960s. Introduced amid the post-World War II demand for computational power in scientific and business applications, the series began with the vacuum-tube-based 700 models in 1952 and progressed to the transistorized 7000 models by 1959, representing a pivotal shift in technology that enhanced reliability, speed, and efficiency.[1][3] The series featured six distinct incompatible processor architectures, reflecting IBM's tailored approaches to diverse computing needs during an era of rapid innovation. The 700 series (1952–1955) relied on vacuum tubes for logic, while the 7000 series (1959–1964) adopted discrete transistors, enabling more compact and power-efficient designs. These architectures were broadly categorized into scientific systems emphasizing binary floating-point operations for complex calculations, commercial variants supporting variable-word alphanumeric data handling, and decimal architectures using fixed-word binary-coded decimal (BCD) formats optimized for business data processing.[3][15] Production volumes varied significantly, with early 700 series models like the 701 limited to 19 units due to their specialized scientific focus and high cost. Later models in the 7000 series, such as the 7090, achieved broader adoption with production scaling into the hundreds, contributing to thousands of systems overall and solidifying IBM's market position. However, the proliferation of incompatible designs created substantial challenges for software portability and customer migration, culminating in the announcement of the unified System/360 in 1964, with initial deliveries in 1965, which ultimately supplanted the 700/7000 line.[16][1]Scientific Architectures

701 Defense Calculator

The IBM 701, initially developed under the codename Defense Calculator, was announced by IBM on May 21, 1952, marking the company's entry into commercial electronic computing for scientific applications. The first production unit was delivered in December 1952 to IBM's world headquarters in New York City, where it functioned as a demonstration and service bureau machine for potential customers. Available only on a rental basis at $15,000 per month, the system was targeted at defense-related organizations and research institutions, reflecting the era's emphasis on computational support for national security projects.[17] The 701 employed a 36-bit binary word architecture, with each instruction occupying 18 bits to enable packing two instructions per word for efficient memory utilization. Primary storage relied on electrostatic Williams-Kilburn tubes, initially providing 2,048 words (expandable to 4,096 words via additional units), while secondary storage used magnetic drums capable of holding up to 4,096 words across multiple units for buffering programs and data. Arithmetic and logical operations were performed using fixed-point signed-magnitude representation, with the accumulator serving as the primary register for computations.[18][19] Central to the 701's design were its Williams-Kilburn tube memory units, which stored data as charge patterns on cathode-ray tube screens for rapid random access, supplemented by electrostatic storage tubes for temporary holding during operations. The memory cycle time was 12 microseconds, enabling approximately 16,000 additions and 2,000 multiplications per second, though the tubes required constant refreshing to prevent data loss and contributed to reliability challenges. Vacuum-tube logic circuits handled control and processing, with the system consuming significant power and generating substantial heat in its eleven-unit configuration.[20][19][1] Primarily deployed for defense and scientific workloads, the 701 supported U.S. Air Force projects involving aerodynamic and ballistics computations, as well as nuclear simulations at Los Alamos National Laboratory, where the second unit was installed in early 1953. Only 19 systems were ultimately produced between 1953 and 1955, with installations concentrated at government labs, aircraft firms, and universities to address complex numerical problems beyond manual or electromechanical capabilities.[21][22] Among its innovations, the 701 introduced a rudimentary assembly language for programming, allowing engineers to encode instructions symbolically before manual translation to machine code, which streamlined development for its single-address instruction set. This machine paved the way for subsequent scientific systems like the IBM 704 by demonstrating scalable electronic computing for real-world research demands.[23]704, 709, 7090, and 7094

The IBM 704, introduced in 1954, represented a major evolution in scientific computing by incorporating hardware support for floating-point arithmetic and index registers that enabled indirect addressing, facilitating more efficient handling of complex numerical simulations.[24] This vacuum-tube machine was the first commercially successful system to integrate these features as standard, allowing for automatic processing of scientific data without manual intervention in arithmetic operations.[25] Its core memory, utilizing innovative ferrite cores for reliability and speed, ranged from 4,096 to 32,768 36-bit words, a significant upgrade over prior electrostatic storage methods that reduced errors in long-running computations.[1] Building on the 704's foundation, the IBM 709, released in 1958, enhanced input/output capabilities through the introduction of separate programmable data channels, which permitted asynchronous I/O operations independent of the central processing unit, thereby boosting overall system throughput for scientific workloads.[26] With a maximum core memory of 32,768 36-bit words, the 709 supported expanded program sizes essential for advanced engineering applications.[27] It continued the support for high-level programming languages like FORTRAN, initially implemented on the 704 in 1957, with subsequent refinements that streamlined scientific coding.[28] The IBM 7090, announced in 1959 and transistorized for greater reliability and efficiency, delivered approximately 1.5 times the performance of the 709 through faster circuitry and a reduced memory cycle time, enabling it to handle demanding simulations at speeds up to 100,000 floating-point operations per second.[29] Supporting up to 32,768 words of core memory, it employed a 36-bit word architecture with support for double-precision floating-point arithmetic (72 bits) to accommodate high-accuracy calculations in fields like physics and aerodynamics. A total of 139 units were produced, reflecting its widespread adoption in research institutions.[30] The IBM 7094, launched in 1962 as an extended variant of the 7090, further improved scalability by supporting up to 8 I/O channels for concurrent data handling, which was crucial for real-time processing in large-scale projects.[31] It retained the core memory capacity of up to 32,768 words while enhancing instruction execution for complex trajectories and simulations.[32] Notably, the 7094 was integral to NASA's Project Mercury, where it computed orbital paths and mission parameters for the 1962 manned suborbital and orbital flights, ensuring precise ground control support.[33] To support programming on these systems, the FORTRAN Assembly Program (FAP) was developed specifically for the 709, 7090, and 7094, offering symbolic assembly language features, macro instructions for code reuse, and built-in optimization tools to generate efficient machine code under the IBSYS operating system and FMS monitor.[34] FAP's versatility allowed programmers to mix high-level FORTRAN constructs with low-level assembly, accelerating development for scientific applications while minimizing execution overhead.[35] Production across the series underscored their impact: 123 units of the 704, 78 of the 709, 139 of the 7090, and approximately 130 Model I and 125 Model II units of the 7094 (totaling 255) were manufactured, with the latter two models benefiting from transistor technology to meet growing demand in scientific computing.[36][24][37] These systems often shared peripherals, such as the IBM 727 magnetic tape drives, for reliable data storage and transfer.[1]Business Architectures

Early Commercial Systems (702, 705, 7080)

The IBM 702, delivered starting in July 1955, represented IBM's initial foray into large-scale commercial computing with a vacuum-tube-based design optimized for business data processing. It featured electrostatic memory with a capacity of 10,000 alphanumeric characters and supported variable-length fields up to 511 characters, enabling flexible handling of accounting records without fixed word boundaries. Auxiliary storage was provided by magnetic drums, expandable to 30 units holding up to 1.8 million characters total, emphasizing high-capacity I/O for tasks like report generation. Only 14 units were produced, reflecting its niche role in early enterprise automation.[38][39][40] Building on the 702, the IBM 705, introduced in 1955, integrated punched-card readers and printers directly into its architecture to streamline data entry and output for commercial workflows. It employed magnetic core memory as its primary storage—the first such implementation in a commercial system—with capacities of 20,000 characters for Model I and 40,000 characters for Models II and III, expandable via auxiliary magnetic drums holding 60,000 characters each. The system offered three variants (I, II, and III) with escalating complexity: the base model focused on basic arithmetic and I/O, while higher variants added more processing units and storage for complex tabulations. This design prioritized decimal arithmetic and variable field lengths for overlapping data in business reports, such as ledgers and inventories, without support for floating-point operations.[41][42] The IBM 7080, announced in 1961, marked a transistorized evolution of the 705 series, delivering significantly enhanced performance for large-scale business applications. It utilized magnetic core memory expandable to 160,000 alphanumeric characters with a character cycle time of 2.18 microseconds, enabling faster processing of variable-length fields for efficient report formatting and data manipulation. Compatibility modes allowed emulation of 705 I, II, and III configurations, facilitating migration of existing programs while introducing advanced I/O channels for high-volume accounting tasks. Deployed in sectors like banking for transaction processing and inventory management, as well as insurance firms handling policy calculations, the 7080 underscored the series' emphasis on robust peripheral integration over scientific computation. It could optionally pair with the IBM 1401 for accelerated I/O in hybrid setups.[43]Decimal Business Systems (1400 Series, 7010, 7070, 7072, 7074)

The IBM 1400 series, introduced between 1959 and 1963, represented a line of low-cost, transistorized decimal computers designed for mid-range business applications, emphasizing affordability and ease of use for smaller organizations transitioning from unit-record equipment. The flagship model, the IBM 1401, featured magnetic core memory with capacities ranging from 1,400 to 16,000 alphanumeric characters, utilizing binary-coded decimal (BCD) arithmetic for precise handling of business data such as financial records and inventories. Each memory location stored 8 bits, including 6 bits for BCD encoding (4-bit numeric digit and 2-bit zone), a parity bit for error detection, and a word mark bit to delineate variable-length fields, enabling flexible data processing without fixed word boundaries. The system's cycle time was approximately 11.5 microseconds, supporting operations like addition in as little as 2.2 milliseconds for short fields. Priced for lease at around $2,500 per month—significantly lower than prior mainframes—the 1401 achieved widespread adoption, with over 10,000 units installed globally by the mid-1960s, accounting for nearly half of all computers in use worldwide at that time.[44][45] Key to the 1400 series' success was its focus on practical business tasks, including payroll processing, billing, accounts receivable, and inventory control, often replacing manual punched-card workflows with automated batch operations. The 1401 integrated peripherals like the 1402 card read-punch (up to 800 cards per minute read speed) and the 1403 line printer (600 lines per minute), allowing seamless input from punched cards and magnetic tapes while outputting reports or updated records. BCD arithmetic ensured exact decimal representations without rounding errors common in binary systems, making it ideal for monetary calculations. Frequently deployed as satellite processors, 1401 systems offloaded data preparation and reporting tasks from larger mainframes, enhancing overall efficiency in enterprise environments such as banking and insurance. Programming was facilitated through assembly languages like Autocoder and higher-level tools like RPG, with over 1,000 units delivered in markets like Germany alone by 1962, underscoring its rapid proliferation.[44][46][45] Building on the 1400 series architecture, the IBM 7010, announced in 1960 and shipped starting in 1962, served as a mainframe-scale extension of the IBM 1410 model, targeting larger-scale commercial installations requiring expanded capacity. It retained the variable-word BCD design but scaled memory to 40,000, 60,000, 80,000, or 100,000 character positions in core storage, organized similarly with 8-bit words including parity and word marks. This allowed handling of more complex datasets, such as high-volume transaction processing, while maintaining compatibility with 1400 series peripherals and software. The 7010's processing unit, the IBM 7114, supported similar instruction sets for arithmetic and I/O operations, with enhancements for multi-programming and direct disk access via units like the IBM 1301, providing up to 28 million characters of online storage. Though produced in smaller numbers than the 1401, it bridged mid-range and high-end business computing, often used in conjunction with tape drives for data interchange.[47] The IBM 7070 series, introduced in 1960, marked IBM's shift to fully transistorized decimal mainframes optimized for business data processing, differing from the variable-length fields of the 1400 series by employing fixed 10-digit BCD words (plus sign) for streamlined arithmetic and reduced programming complexity. The base 7070 model offered core memory of 5,000 or 9,990 words, with an access time of 6 microseconds and addition times around 72 microseconds, enabling efficient handling of decimal operations without floating-point support to prioritize accuracy in financial computations. It featured three accumulators, 99 index registers, and an instruction set supporting block transfers, table lookups, and shifts, all executed in a memory-to-memory paradigm using parallel transmission channels. Peripherals included up to 40 magnetic tape units, disk storage (up to 48 million digits across four IBM 7300 drives), and unit-record devices like card readers (500 cards per minute) and printers (150 lines per minute), facilitating high-throughput batch jobs.[48] Variants expanded the 7070's capabilities: the IBM 7072, released in 1962, increased memory to support up to 20,000 words in some configurations, improving capacity for growing datasets, while the IBM 7074, introduced in 1961 (with broader availability by 1964), integrated advanced I/O controls and faster 4-microsecond access times, allowing up to 30,000 words of extended core and concurrent operations across multiple channels for enhanced multitasking. These models maintained the fixed-word decimal focus, with no native floating-point but optional features for scientific-like calculations when needed, and emphasized self-checking mechanisms for reliability in production environments. Primarily applied to payroll, billing, and general ledger tasks in medium-to-large businesses, the 7070 series saw production in the low hundreds of units overall, reflecting its niche as a bridge to more universal architectures like the System/360, which later emulated these systems for seamless migration.[49][48]System Components

Peripherals

The IBM 700/7000 series relied on a range of peripheral devices for input, output, and secondary storage, enabling efficient data handling in both scientific and commercial applications across the family. Magnetic tape units, punched card readers/punches, printers, and emerging disk storage systems formed the core of these I/O capabilities, with innovations like dedicated channels improving overall system throughput.[50] The IBM 727 Magnetic Tape Unit, introduced in 1953, served as an early standard tape drive for the initial models in the series, later supplemented by the faster IBM 729 units for subsequent systems, utilizing 7-track magnetic tape on 10.5-inch reels at a recording density of 200 bits per inch (bpi), with a maximum capacity of approximately 2.3 million characters per reel.[51] Later models predominantly used the IBM 729 Magnetic Tape Unit (1957), which offered higher tape speeds of 112.5 inches per second, recording densities up to 800 bpi, and capacities of approximately 10 million characters per reel.[52] Punched card input and output were handled primarily by the IBM 1402 Card Read-Punch, which could read up to 800 cards per minute and punch at 250 cards per minute, available in integrated or standalone configurations to accommodate varying workloads. This device used standard 80-column Hollerith cards, supporting hopper capacities of 1,200 cards for input and multiple 1,000-card stackers for output, thus streamlining data entry and report generation.[53][54] Early systems like the IBM 702 employed magnetic drum storage for auxiliary memory, with each drum unit offering 5,000 to 10,000 character capacity, divided into addressable sections for temporary data buffering. Later models shifted toward core memory dominance for primary storage, but disk systems such as the IBM 1301, announced in 1961 for the 7070 and 7080, provided random-access secondary storage with up to 28 million characters per module using flying-head technology for faster access times.[55][56] High-speed printing was achieved with the IBM 1403 line printer, capable of producing 600 lines per minute on continuous forms up to 132 characters wide, essential for generating detailed reports and listings in business environments.[57] Input/output innovations included separate data channels introduced in the IBM 709 and carried forward to the 7090, allowing concurrent I/O operations independent of the CPU via programmable synchronizers like the IBM 766, which supported up to three channels for enhanced peripheral efficiency.[26][58] The Direct Coupled System (DCS) enabled pairing of the IBM 7094 with a lower-cost IBM 1401 as a satellite processor, facilitating offline tasks such as tape-to-card conversion and reducing the mainframe's I/O burden through a specialized interface. This configuration was commonly used to optimize workflows, with the 1401 handling peripheral operations like reading tapes and punching cards autonomously.[59]Software and Compatibility

The IBM 700/7000 series computers were programmed using low-level assembly languages tailored to their distinct architectures, reflecting the era's emphasis on machine-specific coding. For the scientific-oriented 701 and 704 models, programmers employed the Symbolic Assembly Program (SAP), an early assembler that allowed symbolic notation for instructions, easing the transition from absolute machine code addressing. Similarly, the commercial 702 utilized a Basic Assembly Program (BAP) to generate object code from symbolic inputs, supporting decimal arithmetic operations essential for business applications. These assemblers were essential due to the absence of standardized higher-level languages in the early 1950s, requiring programmers to manage memory and I/O directly.[38][55] As the series evolved, more advanced software environments emerged to support scientific computing. The FORTRAN Monitor System (FMS), developed initially for the 709 by North American Aviation, provided a tape-based batch processing framework that integrated the FORTRAN compiler with utility routines for job control, input/output management, and program loading. FMS enabled sequential execution of FORTRAN programs without constant operator intervention, marking an early step toward automated workflow in scientific applications. For the later 7090 and 7094 models, the IBSYS operating system superseded FMS, offering a comprehensive suite of subsystems including the FORTRAN IV compiler (IBFTC), COBOL compiler (IBCBC), and a symbolic assembler, along with utilities for tape dumping, disk file maintenance, and linkage editing. IBSYS facilitated batch processing through its IBJOB processor, which compiled, assembled, loaded, and executed multiple source-language programs in a single job stream, improving efficiency for both commercial and scientific workloads.[60][61][62][63][64] Despite these advancements, software compatibility across the 700/7000 series posed significant challenges, stemming from six distinct processor architectures—binary scientific (701/704/709/7090/7094), alphanumeric commercial (702/705/7080), and decimal business (7070/7072/7074), among others—that lacked binary or source-level interchangeability. This fragmentation necessitated entirely separate codebases and recompilation efforts for each machine, resulting in substantial development and maintenance costs estimated in the millions for large installations. The incompatibility exacerbated migration difficulties when IBM introduced the System/360 in 1964, as customers faced extensive rewriting of legacy applications to leverage the new unified architecture. To mitigate these issues, IBM developed emulation solutions; by 1965, System/360 models incorporated optional compatibility features, including emulators for the 1401, 7010, and 7070 that allowed unmodified programs to run under OS/360 control, preserving investments in existing software. Additionally, the 7080 provided built-in operational modes mimicking the 705 I, II, and III systems, enabling direct execution of 705 programs with minimal modifications through hardware switches that adjusted addressing and instruction sets.[65][66][67][68] Operating system developments in the series emphasized batch processing to optimize resource utilization on expensive hardware, but lacked advanced features like true multiprogramming in most implementations. IBSYS, for instance, supported sequential job execution with limited overlap for peripheral operations via its Input/Output Control System (IOCS), but confined core memory to a single active program, relying on operator intervention for job transitions. No full multiprogramming—allowing multiple concurrent computations in shared memory—was available until experimental systems on late models like the 7094, such as the Compatible Time-Sharing System (CTSS), introduced rudimentary task switching in 1961. These limitations highlighted the series' transitional role, paving the way for the more sophisticated, compatible environments of subsequent IBM systems.[32]Timeline and Assessment

Release Timeline

The IBM 700/7000 series began with the announcement of the IBM 701 on May 21, 1952, marking IBM's entry into the market for large-scale stored-program electronic computers designed primarily for scientific and defense applications.[69] The 701, often called the Defense Calculator, was the company's first such system, with initial orders from 18 customers placed shortly after in May 1952.[1] Its first installation occurred in April 1953 at Los Alamos National Laboratory.[70] In 1953, IBM expanded the series commercially with the announcement of the IBM 702 on September 25, 1953, targeted at business data processing.[40] The first 702 was delivered in July 1955.[40] By 1954, the lineup advanced with the IBM 704 announced on May 7, 1954, introducing innovations like magnetic core memory and floating-point arithmetic for scientific computing.[71] The first 704 was installed in April 1955 at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.[72] Concurrently, the IBM 705 was announced on October 1, 1954, as a business-oriented successor to the 702, with initial deliveries starting in 1956.[73] The series continued evolving in 1957 with the announcement of the IBM 709 on January 2, 1957, enhancing capabilities for large-scale scientific tasks, and its first delivery in late summer 1958.[74][26] A key milestone that year was the debut of FORTRAN, IBM's seminal programming language, initially implemented on the 704 to simplify scientific coding.[75] In 1958, the IBM 7090 was announced in December, representing the series' shift to transistorized logic for improved reliability and speed.[76] Its first deliveries occurred on November 30, 1959, to General Electric and Lawrence Radiation Laboratory.[77] Also in 1959, the IBM 1401 was announced on October 5 as the entry point to the 1400 series within the broader 700/7000 family, with shipments beginning in 1960.[44] The 1960s saw further business-focused expansions, including the announcement of the IBM 7070 in June 1960 and the IBM 7074 in July 1960, both transistorized systems for data processing, with initial deliveries starting in late 1960.[78] In 1961, the IBM 7080 was announced in August and delivered, building on the 708/7080 line for commercial applications. The IBM 7030 "Stretch" supercomputer, announced in May 1956, saw its first delivery in March 1961 to Los Alamos National Laboratory.[4] By 1962, announcements included the IBM 7072 in November, the IBM 7094 in January, and the IBM 7010 in 1962, the latter supporting critical applications such as NASA's Mercury space program for real-time trajectory computations.[79][80][81] Deliveries of the IBM 7094 II followed in 1964, but the series' trajectory shifted with IBM's announcement of the System/360 on April 7, 1964, which ultimately superseded the 700/7000 architecture.[82][83]| Year | Model(s) | Key Event(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1952 | 701 | Announced May 21; first stored-program computer from IBM.[69][1] |

| 1953 | 701, 702 | 701 first delivered April; 702 announced September 25.[70][40] |

| 1954 | 704, 705 | Both announced (704: May 7; 705: October 1); 704 first delivered April 1955.[71][73][72] |

| 1956 | 7030 | Stretch announced May.[4] |

| 1957 | 709 | Announced January 2; FORTRAN debuted on 704.[74][75] |

| 1958 | 709 | First delivered late summer; 7090 announced December (transistor shift).[26][76] |

| 1959 | 7090, 1401 | 7090 first delivered November 30; 1401 announced October 5.[77][44] |

| 1960 | 7070, 7074 | Both announced (7070: June; 7074: July) and initial deliveries.[78] |

| 1961 | 7030, 7080 | Stretch first delivered March; 7080 announced August and delivered.[4] |

| 1962 | 7010, 7072, 7094 | 7010 announced; 7072 announced November; 7094 announced January; 7094 used in Mercury program.[81][79][80] |

| 1964 | 7094 II, System/360 | 7094 II delivered; System/360 announced April 7, ending series focus.[82][83] |

Performance Metrics

The performance of the IBM 700/7000 series was evaluated using early benchmarks like the Gibson mix, which measured kilo-instructions per second (KIPS) based on a weighted combination of typical scientific computing operations, including arithmetic, data transfer, and indexing. For the IBM 709, this benchmark yielded 21 KIPS, while the transistorized IBM 7090 achieved 139 KIPS, reflecting improvements in instruction execution speed and floating-point hardware.[84] The IBM 701, an early vacuum-tube system, was capable of approximately 16,000 additions or subtractions per second, establishing a baseline for series performance in basic arithmetic tasks.[1] These metrics highlighted the series' progression from vacuum-tube limitations to transistor-based efficiency, with the 7090 demonstrating roughly 10 times the overall computational throughput of the 701 through faster cycle times and optimized instruction sets.[85] Scientific workloads often emphasized floating-point operations, where the 7090 excelled with up to 210,000 floating-point additions per second, far surpassing the 701's baseline performance normalized at 1.0 on indices like the Knight scale for such tasks.[85] In three-dimensional integration tests using the TRIDIA FORTRAN program, related systems like the IBM 7030 completed runs in 15.58 seconds, while the 7090 achieved approximately 10 seconds, underscoring its advantage in complex simulations.[84] For business-oriented models, the IBM 7080 was estimated at around 100 KIPS on similar mixes, bridging commercial data processing with scientific capabilities.[86] Memory access times varied significantly across the series, impacting overall system responsiveness. The IBM 701 relied on magnetic drum storage with an average access time of 17 milliseconds, suitable for auxiliary data but limiting random access speeds.[87] In contrast, the IBM 7090 used core memory with a cycle time of 2.18 microseconds, enabling much faster data retrieval and supporting high-throughput computations.[88] Input/output throughput was enhanced by peripherals like the IBM 727 magnetic tape drive, which delivered 15,000 characters per second at 200 bits per inch density and 75 inches per second tape speed.[89] Pairing larger systems such as the 7090 with an IBM 1401 for spooling improved I/O efficiency by offloading peripheral operations, potentially accelerating data transfer by up to 50% in tape-based workflows.[59] These benchmarks, including Gibson mix results, were instrumental in NASA applications for trajectory calculations and simulations on 7090 systems.[90]| Model | Gibson Mix (KIPS) | Key Operation Rate | Memory Access Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| IBM 701 | N/A | 16,000 additions/sec | 17 ms (drum avg.) |

| IBM 704 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| IBM 7090 | 139 | 210,000 FP adds/sec | 2.18 μs (core cycle) |

| IBM 7080 | ~100 (est.) | N/A | N/A |