Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Floating-point arithmetic

View on Wikipedia

| Floating-point formats |

|---|

| IEEE 754 |

|

| Other |

| Alternatives |

| Tapered floating point |

In computing, floating-point arithmetic (FP) is arithmetic on subsets of real numbers formed by a significand (a signed sequence of a fixed number of digits in some base) multiplied by an integer power of that base. Numbers of this form are called floating-point numbers.[1]: 3 [2]: 10

For example, the number 2469/200 is a floating-point number in base ten with five digits: However, 7716/625 = 12.3456 is not a floating-point number in base ten with five digits—it needs six digits. The nearest floating-point number with only five digits is 12.346. And 1/3 = 0.3333… is not a floating-point number in base ten with any finite number of digits. In practice, most floating-point systems use base two, though base ten (decimal floating point) is also common.

Floating-point arithmetic operations, such as addition and division, approximate the corresponding real number arithmetic operations by rounding any result that is not a floating-point number itself to a nearby floating-point number.[1]: 22 [2]: 10 For example, in a floating-point arithmetic with five base-ten digits, the sum 12.345 + 1.0001 = 13.3451 might be rounded to 13.345.

The term floating point refers to the fact that the number's radix point can "float" anywhere to the left, right, or between the significant digits of the number. This position is indicated by the exponent, so floating point can be considered a form of scientific notation.

A floating-point system can be used to represent, with a fixed number of digits, numbers of very different orders of magnitude — such as the number of meters between galaxies or between protons in an atom. For this reason, floating-point arithmetic is often used to allow very small and very large real numbers that require fast processing times. The result of this dynamic range is that the numbers that can be represented are not uniformly spaced; the difference between two consecutive representable numbers varies with their exponent.[3]

Over the years, a variety of floating-point representations have been used in computers. In 1985, the IEEE 754 Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic was established, and since the 1990s, the most commonly encountered representations are those defined by the IEEE.

The speed of floating-point operations, commonly measured in terms of FLOPS, is an important characteristic of a computer system, especially for applications that involve intensive mathematical calculations.

Floating-point numbers can be computed using software implementations (softfloat) or hardware implementations (hardfloat). Floating-point units (FPUs, colloquially math coprocessors) are specially designed to carry out operations on floating-point numbers and are part of most computer systems. When FPUs are not available, software implementations can be used instead.

Overview

[edit]Floating-point numbers

[edit]A number representation specifies some way of encoding a number, usually as a string of digits.

There are several mechanisms by which strings of digits can represent numbers. In standard mathematical notation, the digit string can be of any length, and the location of the radix point is indicated by placing an explicit "point" character (dot or comma) there. If the radix point is not specified, then the string implicitly represents an integer and the unstated radix point would be off the right-hand end of the string, next to the least significant digit. In fixed-point systems, a position in the string is specified for the radix point. So a fixed-point scheme might use a string of 8 decimal digits with the decimal point in the middle, whereby "00012345" would represent 0001.2345.

In scientific notation, the given number is scaled by a power of 10, so that it lies within a specific range—typically between 1 and 10, with the radix point appearing immediately after the first digit. As a power of ten, the scaling factor is then indicated separately at the end of the number. For example, the orbital period of Jupiter's moon Io is 152,853.5047 seconds, a value that would be represented in standard-form scientific notation as 1.528535047×105 seconds.

Floating-point representation is similar in concept to scientific notation. Logically, a floating-point number consists of:

- A signed (meaning positive or negative) digit string of a given length in a given radix (or base). This digit string is referred to as the significand, mantissa, or coefficient.[nb 1] The length of the significand determines the precision to which numbers can be represented. The radix point position is assumed always to be somewhere within the significand—often just after or just before the most significant digit, or to the right of the rightmost (least significant) digit. This article generally follows the convention that the radix point is set just after the most significant (leftmost) digit.

- A signed integer exponent (also referred to as the characteristic, or scale),[nb 2] which modifies the magnitude of the number.

To derive the value of the floating-point number, the significand is multiplied by the base raised to the power of the exponent, equivalent to shifting the radix point from its implied position by a number of places equal to the value of the exponent—to the right if the exponent is positive or to the left if the exponent is negative.

Using base-10 (the familiar decimal notation) as an example, the number 152,853.5047, which has ten decimal digits of precision, is represented as the significand 1528535047 together with 5 as the exponent. To determine the actual value, a decimal point is placed after the first digit of the significand and the result is multiplied by 105 to give 1.528535047×105, or 152,853.5047. In storing such a number, the base (10) need not be stored, since it will be the same for the entire range of supported numbers, and can thus be inferred.

Symbolically, this final value is:

where s is the significand (ignoring any implied decimal point), p is the precision (the number of digits in the significand), b is the base (in our example, this is the number ten), and e is the exponent.

Historically, several number bases have been used for representing floating-point numbers, with base two (binary) being the most common, followed by base ten (decimal floating point), and other less common varieties, such as base sixteen (hexadecimal floating point[4][5][nb 3]), base eight (octal floating point[1][5][6][4][nb 4]), base four (quaternary floating point[7][5][nb 5]), base three (balanced ternary floating point[1]) and even base 256[5][nb 6] and base 65,536.[8][nb 7]

A floating-point number is a rational number, because it can be represented as one integer divided by another; for example 1.45×103 is (145/100)×1000 or 145,000/100. The base determines the fractions that can be represented; for instance, 1/5 cannot be represented exactly as a floating-point number using a binary base, but 1/5 can be represented exactly using a decimal base (0.2, or 2×10−1). However, 1/3 cannot be represented exactly by either binary (0.010101...) or decimal (0.333...), but in base 3, it is trivial (0.1 or 1×3−1) . The occasions on which infinite expansions occur depend on the base and its prime factors.

The way in which the significand (including its sign) and exponent are stored in a computer is implementation-dependent. The common IEEE formats are described in detail later and elsewhere, but as an example, in the binary single-precision (32-bit) floating-point representation, , and so the significand is a string of 24 bits. For instance, the number π's first 33 bits are:

In this binary expansion, let us denote the positions from 0 (leftmost bit, or most significant bit) to 32 (rightmost bit). The 24-bit significand will stop at position 23, shown as the underlined bit 0 above. The next bit, at position 24, is called the round bit or rounding bit. It is used to round the 33-bit approximation to the nearest 24-bit number (there are specific rules for halfway values, which is not the case here). This bit, which is 1 in this example, is added to the integer formed by the leftmost 24 bits, yielding:

When this is stored in memory using the IEEE 754 encoding, this becomes the significand s. The significand is assumed to have a binary point to the right of the leftmost bit. So, the binary representation of π is calculated from left-to-right as follows:

where p is the precision (24 in this example), n is the position of the bit of the significand from the left (starting at 0 and finishing at 23 here) and e is the exponent (1 in this example).

It can be required that the most significant digit of the significand of a non-zero number be non-zero (except when the corresponding exponent would be smaller than the minimum one). This process is called normalization. For binary formats (which uses only the digits 0 and 1), this non-zero digit is necessarily 1. Therefore, it does not need to be represented in memory, allowing the format to have one more bit of precision. This rule is variously called the leading bit convention, the implicit bit convention, the hidden bit convention,[1] or the assumed bit convention.

Alternatives to floating-point numbers

[edit]The floating-point representation is by far the most common way of representing in computers an approximation to real numbers. However, there are alternatives:

- Fixed-point representation uses integer hardware operations controlled by a software implementation of a specific convention about the location of the binary or decimal point, for example, 6 bits or digits from the right. The hardware to manipulate these representations is less costly than floating point, and it can be used to perform normal integer operations, too. Binary fixed point is usually used in special-purpose applications on embedded processors that can only do integer arithmetic, but decimal fixed point is common in commercial applications.

- Logarithmic number systems (LNSs) represent a real number by the logarithm of its absolute value and a sign bit. The value distribution is similar to floating point, but the value-to-representation curve (i.e., the graph of the logarithm function) is smooth (except at 0). Conversely to floating-point arithmetic, in a logarithmic number system multiplication, division and exponentiation are simple to implement, but addition and subtraction are complex. The (symmetric) level-index arithmetic (LI and SLI) of Charles Clenshaw, Frank Olver and Peter Turner is a scheme based on a generalized logarithm representation.

- Tapered floating-point representation, used in Unum formats, including Posit.

- Some simple rational numbers (e.g., 1/3 and 1/10) cannot be represented exactly in binary floating point, no matter what the precision is. Using a different radix allows one to represent some of them (e.g., 1/10 in decimal floating point), but the possibilities remain limited. Software packages that perform rational arithmetic represent numbers as fractions with integral numerator and denominator, and can therefore represent any rational number exactly. Such packages generally need to use "bignum" arithmetic for the individual integers.

- Interval arithmetic allows one to represent numbers as intervals and obtain guaranteed bounds on results. It is generally based on other arithmetics, in particular floating point.

- Computer algebra systems such as Mathematica, Maxima, and Maple can often handle irrational numbers like or in a completely "formal" way (symbolic computation), without dealing with a specific encoding of the significand. Such a program can evaluate expressions like "" exactly, because it is programmed to process the underlying mathematics directly, instead of using approximate values for each intermediate calculation.

History

[edit]

In 1914, the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo published Essays on Automatics,[9] where he designed a special-purpose electromechanical calculator based on Charles Babbage's analytical engine and described a way to store floating-point numbers in a consistent manner. He stated that numbers will be stored in exponential format as n × 10, and offered three rules by which consistent manipulation of floating-point numbers by machines could be implemented. For Torres, "n will always be the same number of digits (e.g. six), the first digit of n will be of order of tenths, the second of hundredths, etc, and one will write each quantity in the form: n; m." The format he proposed shows the need for a fixed-sized significand as is presently used for floating-point data, fixing the location of the decimal point in the significand so that each representation was unique, and how to format such numbers by specifying a syntax to be used that could be entered through a typewriter, as was the case of his Electromechanical Arithmometer in 1920.[10][11][12]

In 1938, Konrad Zuse of Berlin completed the Z1, the first binary, programmable mechanical computer;[13] it uses a 24-bit binary floating-point number representation with a 7-bit signed exponent, a 17-bit significand (including one implicit bit), and a sign bit.[14] The more reliable relay-based Z3, completed in 1941, has representations for both positive and negative infinities; in particular, it implements defined operations with infinity, such as , and it stops on undefined operations, such as .

Zuse also proposed, but did not complete, carefully rounded floating-point arithmetic that includes and NaN representations, anticipating features of the IEEE Standard by four decades.[15] In contrast, von Neumann recommended against floating-point numbers for the 1951 IAS machine, arguing that fixed-point arithmetic is preferable.[15]

The first commercial computer with floating-point hardware was Zuse's Z4 computer, designed in 1942–1945. In 1946, Bell Laboratories introduced the Model V, which implemented decimal floating-point numbers.[16]

The Pilot ACE has binary floating-point arithmetic, and it became operational in 1950 at National Physical Laboratory, UK. Thirty-three were later sold commercially as the English Electric DEUCE. The arithmetic is actually implemented in software, but with a one megahertz clock rate, the speed of floating-point and fixed-point operations in this machine were initially faster than those of many competing computers.

The mass-produced IBM 704 followed in 1954; it introduced the use of a biased exponent. For many decades after that, floating-point hardware was typically an optional feature, and computers that had it were said to be "scientific computers", or to have "scientific computation" (SC) capability (see also Extensions for Scientific Computation (XSC)). It was not until the launch of the Intel i486 in 1989 that general-purpose personal computers had floating-point capability in hardware as a standard feature.

The UNIVAC 1100/2200 series, introduced in 1962, supported two floating-point representations:

- Single precision: 36 bits, organized as a 1-bit sign, an 8-bit exponent, and a 27-bit significand.

- Double precision: 72 bits, organized as a 1-bit sign, an 11-bit exponent, and a 60-bit significand.

The IBM 7094, also introduced in 1962, supported single-precision and double-precision representations, but with no relation to the UNIVAC's representations. Indeed, in 1964, IBM introduced hexadecimal floating-point representations in its System/360 mainframes; these same representations are still available for use in modern z/Architecture systems. In 1998, IBM implemented IEEE-compatible binary floating-point arithmetic in its mainframes; in 2005, IBM also added IEEE-compatible decimal floating-point arithmetic.

Initially, computers used many different representations for floating-point numbers. The lack of standardization at the mainframe level was an ongoing problem by the early 1970s for those writing and maintaining higher-level source code; these manufacturer floating-point standards differed in the word sizes, the representations, and the rounding behavior and general accuracy of operations. Floating-point compatibility across multiple computing systems was in desperate need of standardization by the early 1980s, leading to the creation of the IEEE 754 standard once the 32-bit (or 64-bit) word had become commonplace. This standard was significantly based on a proposal from Intel, which was designing the i8087 numerical coprocessor; Motorola, which was designing the 68000 around the same time, gave significant input as well.

In 1989, mathematician and computer scientist William Kahan was honored with the Turing Award for being the primary architect behind this proposal; he was aided by his student Jerome Coonen and a visiting professor, Harold Stone.[17]

Among the x86 (more specifically i8087) innovations are these:

- A precisely specified floating-point representation at the bit-string level, so that all compliant computers interpret bit patterns the same way. This makes it possible to accurately and efficiently transfer floating-point numbers from one computer to another (after accounting for endianness).

- A precisely specified behavior for the arithmetic operations: A result is required to be produced as if infinitely precise arithmetic were used to yield a value that is then rounded according to specific rules. This means that a compliant computer program would always produce the same result when given a particular input, thus mitigating the almost mystical reputation that floating-point computation had developed for its hitherto seemingly non-deterministic behavior.

- The ability of exceptional conditions (overflow, divide by zero, etc.) to propagate through a computation in a benign manner and then be handled by the software in a controlled fashion.

These features would be inherited into IEEE 754-1985 (with the exception of the encoding of special values and exceptions), though the extended internal precision of x87 means it requires explicit rounding of exact results directly to the destination precision in order to match standard IEEE 754 results.[18] However, the behavior may not be the same as a rounding to the destination format due to a possible wider exponent range of the extended format.

Range of floating-point numbers

[edit]A floating-point number consists of two fixed-point components, whose range depends exclusively on the number of bits or digits in their representation. Whereas components linearly depend on their range, the floating-point range linearly depends on the significand range and exponentially on the range of exponent component, which attaches outstandingly wider range to the number.

On a typical computer system, a double-precision (64-bit) binary floating-point number has a coefficient of 53 bits (including 1 implied bit), an exponent of 11 bits, and 1 sign bit. Since 210 = 1024, the complete range of the positive normal floating-point numbers in this format is from 2−1022 ≈ 2 × 10−308 to approximately 21024 ≈ 2 × 10308.

The number of normal floating-point numbers in a system (B, P, L, U) where

- B is the base of the system,

- P is the precision of the significand (in base B),

- L is the smallest exponent of the system,

- U is the largest exponent of the system,

is , or considering the value 0.

There is a smallest positive normal floating-point number,

- Underflow level = UFL = ,

which has a 1 as the leading digit and 0 for the remaining digits of the significand, and the smallest possible value for the exponent.

There is a largest floating-point number,

- Overflow level = OFL = ,

which has B − 1 as the value for each digit of the significand and the largest possible value for the exponent.

In addition, there are representable values strictly between −UFL and UFL. Namely, positive and negative zeros, as well as subnormal numbers.

IEEE 754: floating point in modern computers

[edit]| Floating-point formats |

|---|

| IEEE 754 |

|

| Other |

| Alternatives |

| Tapered floating point |

The IEEE standardized the computer representation for binary floating-point numbers in IEEE 754 (a.k.a. IEC 60559) in 1985. This first standard is followed by almost all modern machines. It was revised in 2008. IBM mainframes support IBM's own hexadecimal floating point format and IEEE 754-2008 decimal floating point in addition to the IEEE 754 binary format. The Cray T90 series had an IEEE version, but the SV1 still uses Cray floating-point format.[citation needed]

The standard provides for many closely related formats, differing in only a few details. Five of these formats are called basic formats, and others are termed extended precision formats and extendable precision format. Three formats are especially widely used in computer hardware and languages:[citation needed]

- Single precision (binary32), usually used to represent the "float" type in the C language family. This is a binary format that occupies 32 bits (4 bytes) and its significand has a precision of 24 bits (about 7 decimal digits).

- Double precision (binary64), usually used to represent the "double" type in the C language family. This is a binary format that occupies 64 bits (8 bytes) and its significand has a precision of 53 bits (about 16 decimal digits).

- Double extended, also ambiguously called "extended precision" format. This is a binary format that occupies at least 79 bits (80 if the hidden/implicit bit rule is not used) and its significand has a precision of at least 64 bits (about 19 decimal digits). The C99 and C11 standards of the C language family, in their annex F ("IEC 60559 floating-point arithmetic"), recommend such an extended format to be provided as "long double".[19] A format satisfying the minimal requirements (64-bit significand precision, 15-bit exponent, thus fitting on 80 bits) is provided by the x86 architecture. Often on such processors, this format can be used with "long double", though extended precision is not available with MSVC.[20] For alignment purposes, many tools store this 80-bit value in a 96-bit or 128-bit space.[21][22] On other processors, "long double" may stand for a larger format, such as quadruple precision,[23] or just double precision, if any form of extended precision is not available.[24]

Increasing the precision of the floating-point representation generally reduces the amount of accumulated round-off error caused by intermediate calculations.[25] Other IEEE formats include:

- Decimal64 and decimal128 floating-point formats. These formats (especially decimal128) are pervasive in financial transactions because, along with the decimal32 format, they allow correct decimal rounding.

- Quadruple precision (binary128). This is a binary format that occupies 128 bits (16 bytes) and its significand has a precision of 113 bits (about 34 decimal digits).

- Half precision, also called binary16, a 16-bit floating-point value. It is being used in the NVIDIA Cg graphics language, and in the openEXR standard (where it actually predates the introduction in the IEEE 754 standard).[26][27]

Any integer with absolute value less than 224 can be exactly represented in the single-precision format, and any integer with absolute value less than 253 can be exactly represented in the double-precision format. Furthermore, a wide range of powers of 2 times such a number can be represented. These properties are sometimes used for purely integer data, to get 53-bit integers on platforms that have double-precision floats but only 32-bit integers.

The standard specifies some special values, and their representation: positive infinity (+∞), negative infinity (−∞), a negative zero (−0) distinct from ordinary ("positive") zero, and "not a number" values (NaNs).

Comparison of floating-point numbers, as defined by the IEEE standard, is a bit different from usual integer comparison. Negative and positive zero compare equal, and every NaN compares unequal to every value, including itself. All finite floating-point numbers are strictly smaller than +∞ and strictly greater than −∞, and they are ordered in the same way as their values (in the set of real numbers).

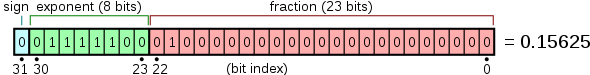

Internal representation

[edit]Floating-point numbers are typically packed into a computer datum as the sign bit, the exponent field, and a field for the significand, from left to right. For the IEEE 754 binary formats (basic and extended) that have extant hardware implementations, they are apportioned as follows:

| Format | Bits for the encoding | Exponent bias |

Bits precision |

Number of decimal digits | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sign | Exponent | Significand | Total | |||||

| Half (binary16) | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 | 15 | 11 | ~3.3 | |

| Single (binary32) | 1 | 8 | 23 | 32 | 127 | 24 | ~7.2 | |

| Double (binary64) | 1 | 11 | 52 | 64 | 1023 | 53 | ~15.9 | |

| x86 extended | 1 | 15 | 64 | 80 | 16383 | 64 | ~19.2 | |

| Quadruple (binary128) | 1 | 15 | 112 | 128 | 16383 | 113 | ~34.0 | |

| Octuple (binary256) | 1 | 19 | 236 | 256 | 262143 | 237 | ~71.3 | |

While the exponent can be positive or negative, in binary formats it is stored as an unsigned number that has a fixed "bias" added to it. Values of all 0s in this field are reserved for the zeros and subnormal numbers; values of all 1s are reserved for the infinities and NaNs. The exponent range for normal numbers is [−126, 127] for single precision, [−1022, 1023] for double, or [−16382, 16383] for quad. Normal numbers exclude subnormal values, zeros, infinities, and NaNs.

In the IEEE binary interchange formats the leading bit of a normalized significand is not actually stored in the computer datum, since it is always 1. It is called the "hidden" or "implicit" bit. Because of this, the single-precision format actually has a significand with 24 bits of precision, the double-precision format has 53, quad has 113, and octuple has 237.

For example, it was shown above that π, rounded to 24 bits of precision, has:

- sign = 0 ; e = 1 ; s = 110010010000111111011011 (including the hidden bit)

The sum of the exponent bias (127) and the exponent (1) is 128, so this is represented in the single-precision format as

- 0 10000000 10010010000111111011011 (excluding the hidden bit) = 40490FDB[28] as a hexadecimal number.

An example of a layout for 32-bit floating point is

and the 64-bit ("double") layout is similar.

Other notable floating-point formats

[edit]In addition to the widely used IEEE 754 standard formats, other floating-point formats are used, or have been used, in certain domain-specific areas.

- The Microsoft Binary Format (MBF) was developed for the Microsoft BASIC language products, including Microsoft's first ever product the Altair BASIC (1975), TRS-80 LEVEL II, CP/M's MBASIC, IBM PC 5150's BASICA, MS-DOS's GW-BASIC and QuickBASIC prior to version 4.00. QuickBASIC version 4.00 and 4.50 switched to the IEEE 754-1985 format but can revert to the MBF format using the /MBF command option. MBF was designed and developed on a simulated Intel 8080 by Monte Davidoff, a dormmate of Bill Gates, during spring of 1975 for the MITS Altair 8800. The initial release of July 1975 supported a single-precision (32 bits) format due to cost of the MITS Altair 8800 4-kilobytes memory. In December 1975, the 8-kilobytes version added a double-precision (64 bits) format. A single-precision (40 bits) variant format was adopted for other CPU's, notably the MOS 6502 (Apple II, Commodore PET, Atari), Motorola 6800 (MITS Altair 680) and Motorola 6809 (TRS-80 Color Computer). All Microsoft language products from 1975 through 1987 used the Microsoft Binary Format until Microsoft adopted the IEEE 754 standard format in all its products starting in 1988 to their current releases. MBF consists of the MBF single-precision format (32 bits, "6-digit BASIC"),[29][30] the MBF extended-precision format (40 bits, "9-digit BASIC"),[30] and the MBF double-precision format (64 bits);[29][31] each of them is represented with an 8-bit exponent, followed by a sign bit, followed by a significand of respectively 23, 31, and 55 bits.

- The bfloat16 format requires the same amount of memory (16 bits) as the IEEE 754 half-precision format, but allocates 8 bits to the exponent instead of 5, thus providing the same range as a IEEE 754 single-precision number. The tradeoff is a reduced precision, as the trailing significand field is reduced from 10 to 7 bits. This format is mainly used in the training of machine learning models, where range is more valuable than precision. Many machine learning accelerators provide hardware support for this format.

- The TensorFloat-32[32] format combines the 8 bits of exponent of the bfloat16 with the 10 bits of trailing significand field of half-precision formats, resulting in a size of 19 bits. This format was introduced by Nvidia, which provides hardware support for it in the Tensor Cores of its GPUs based on the Nvidia Ampere architecture. The drawback of this format is its size, which is not a power of 2. However, according to Nvidia, this format should only be used internally by hardware to speed up computations, while inputs and outputs should be stored in the 32-bit single-precision IEEE 754 format.[32]

- The Hopper and CDNA 3 architecture GPUs provide two FP8 formats: one with the same numerical range as half-precision (E5M2) and one with higher precision, but less range (E4M3).[33][34]

- The Blackwell and CDNA 4 GPU architecture includes support for FP6 (E3M2 and E2M3) and FP4 (E2M1) formats. FP4 is the smallest floating-point format which allows for all IEEE 754 principles (see minifloat).

| Type | Sign | Exponent | Significand | Total bits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| FP6 (E2M3) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| FP6 (E3M2) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| FP8 (E4M3) | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| FP8 (E5M2) | 1 | 5 | 2 | 8 |

| Half-precision | 1 | 5 | 10 | 16 |

| bfloat16 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 16 |

| TensorFloat-32 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 19 |

| Single-precision | 1 | 8 | 23 | 32 |

| Double-precision | 1 | 11 | 52 | 64 |

| Quadruple-precision | 1 | 15 | 112 | 128 |

| Octuple-precision | 1 | 19 | 236 | 256 |

Representable numbers, conversion and rounding

[edit]By their nature, all numbers expressed in floating-point format are rational numbers with a terminating expansion in the relevant base (for example, a terminating decimal expansion in base-10, or a terminating binary expansion in base-2). Irrational numbers, such as π or , or non-terminating rational numbers, must be approximated. The number of digits (or bits) of precision also limits the set of rational numbers that can be represented exactly. For example, the decimal number 123456789 cannot be exactly represented if only eight decimal digits of precision are available (it would be rounded to one of the two straddling representable values, 12345678 × 101 or 12345679 × 101), the same applies to non-terminating digits (.5 to be rounded to either .55555555 or .55555556).

When a number is represented in some format (such as a character string) which is not a native floating-point representation supported in a computer implementation, then it will require a conversion before it can be used in that implementation. If the number can be represented exactly in the floating-point format then the conversion is exact. If there is not an exact representation then the conversion requires a choice of which floating-point number to use to represent the original value. The representation chosen will have a different value from the original, and the value thus adjusted is called the rounded value.

Whether or not a rational number has a terminating expansion depends on the base. For example, in base-10 the number 1/2 has a terminating expansion (0.5) while the number 1/3 does not (0.333...). In base-2 only rationals with denominators that are powers of 2 (such as 1/2 or 3/16) are terminating. Any rational with a denominator that has a prime factor other than 2 will have an infinite binary expansion. This means that numbers that appear to be short and exact when written in decimal format may need to be approximated when converted to binary floating-point. For example, the decimal number 0.1 is not representable in binary floating-point of any finite precision; the exact binary representation would have a "1100" sequence continuing endlessly:

- e = −4; s = 1100110011001100110011001100110011...,

where, as previously, s is the significand and e is the exponent.

When rounded to 24 bits this becomes

- e = −4; s = 110011001100110011001101,

which is actually 0.100000001490116119384765625 in decimal.

As a further example, the real number π, represented in binary as an infinite sequence of bits is

- 11.0010010000111111011010101000100010000101101000110000100011010011...

but is

- 11.0010010000111111011011

when approximated by rounding to a precision of 24 bits.

In binary single-precision floating-point, this is represented as s = 1.10010010000111111011011 with e = 1. This has a decimal value of

- 3.1415927410125732421875,

whereas a more accurate approximation of the true value of π is

- 3.14159265358979323846264338327950...

The result of rounding differs from the true value by about 0.03 parts per million, and matches the decimal representation of π in the first 7 digits. The difference is the discretization error and is limited by the machine epsilon.

The arithmetical difference between two consecutive representable floating-point numbers which have the same exponent is called a unit in the last place (ULP). For example, if there is no representable number lying between the representable numbers 1.45A70C2216 and 1.45A70C2416, the ULP is 2×16−8, or 2−31. For numbers with a base-2 exponent part of 0, i.e. numbers with an absolute value higher than or equal to 1 but lower than 2, an ULP is exactly 2−23 or about 10−7 in single precision, and exactly 2−53 or about 10−16 in double precision. The mandated behavior of IEEE-compliant hardware is that the result be within one-half of a ULP.

Rounding modes

[edit]Rounding is used when the exact result of a floating-point operation (or a conversion to floating-point format) would need more digits than there are digits in the significand. IEEE 754 requires correct rounding: that is, the rounded result is as if infinitely precise arithmetic was used to compute the value and then rounded (although in implementation only three extra bits are needed to ensure this). There are several different rounding schemes (or rounding modes). Historically, truncation was the typical approach. Since the introduction of IEEE 754, the default method (round to nearest, ties to even, sometimes called Banker's Rounding) is more commonly used. This method rounds the ideal (infinitely precise) result of an arithmetic operation to the nearest representable value, and gives that representation as the result.[nb 8] In the case of a tie, the value that would make the significand end in an even digit is chosen. The IEEE 754 standard requires the same rounding to be applied to all fundamental algebraic operations, including square root and conversions, when there is a numeric (non-NaN) result. It means that the results of IEEE 754 operations are completely determined in all bits of the result, except for the representation of NaNs. ("Library" functions such as cosine and log are not mandated.)

Alternative rounding options are also available. IEEE 754 specifies the following rounding modes:

- round to nearest, where ties round to the nearest even digit in the required position (the default and by far the most common mode)

- round to nearest, where ties round away from zero (optional for binary floating-point and commonly used in decimal)

- round up (toward +∞; negative results thus round toward zero)

- round down (toward −∞; negative results thus round away from zero)

- round toward zero (truncation; it is similar to the common behavior of float-to-integer conversions, which convert −3.9 to −3 and 3.9 to 3)

Alternative modes are useful when the amount of error being introduced must be bounded. Applications that require a bounded error are multi-precision floating-point, and interval arithmetic. The alternative rounding modes are also useful in diagnosing numerical instability: if the results of a subroutine vary substantially between rounding to + and − infinity then it is likely numerically unstable and affected by round-off error.[35]

Binary-to-decimal conversion with minimal number of digits

[edit]Converting a double-precision binary floating-point number to a decimal string is a common operation, but an algorithm producing results that are both accurate and minimal did not appear in print until 1990, with Steele and White's Dragon4. Some of the improvements since then include:

- David M. Gay's dtoa.c, a practical open-source implementation of many ideas in Dragon4.[36]

- Grisu3, with a 4× speedup as it removes the use of bignums. Must be used with a fallback, as it fails for ~0.5% of cases.[37]

- Errol3, an always-succeeding algorithm similar to, but slower than, Grisu3. Apparently not as good as an early-terminating Grisu with fallback.[38]

- Ryū, an always-succeeding algorithm that is faster and simpler than Grisu3.[39]

- Schubfach, an always-succeeding algorithm that is based on a similar idea to Ryū, developed almost simultaneously and independently.[40] Performs better than Ryū and Grisu3 in certain benchmarks.[41]

Many modern language runtimes use Grisu3 with a Dragon4 fallback.[42]

Decimal-to-binary conversion

[edit]The problem of parsing a decimal string into a binary FP representation is complex, with an accurate parser not appearing until Clinger's 1990 work (implemented in dtoa.c).[36] Further work has likewise progressed in the direction of faster parsing.[43]

Floating-point operations

[edit]For ease of presentation and understanding, decimal radix with 7 digit precision will be used in the examples, as in the IEEE 754 decimal32 format. The fundamental principles are the same in any radix or precision, except that normalization is optional (it does not affect the numerical value of the result). Here, s denotes the significand and e denotes the exponent.

Addition and subtraction

[edit]A simple method to add floating-point numbers is to first represent them with the same exponent. In the example below, the second number (with the smaller exponent) is shifted right by three digits, and one then proceeds with the usual addition method:

123456.7 = 1.234567 × 10^5 101.7654 = 1.017654 × 10^2 = 0.001017654 × 10^5

Hence:

123456.7 + 101.7654 = (1.234567 × 10^5) + (1.017654 × 10^2)

= (1.234567 × 10^5) + (0.001017654 × 10^5)

= (1.234567 + 0.001017654) × 10^5

= 1.235584654 × 10^5

In detail:

e=5; s=1.234567 (123456.7) + e=2; s=1.017654 (101.7654)

e=5; s=1.234567 + e=5; s=0.001017654 (after shifting) -------------------- e=5; s=1.235584654 (true sum: 123558.4654)

This is the true result, the exact sum of the operands. It will be rounded to seven digits and then normalized if necessary. The final result is

e=5; s=1.235585 (final sum: 123558.5)

The lowest three digits of the second operand (654) are essentially lost. This is round-off error. In extreme cases, the sum of two non-zero numbers may be equal to one of them:

e=5; s=1.234567 + e=−3; s=9.876543

e=5; s=1.234567 + e=5; s=0.00000009876543 (after shifting) ---------------------- e=5; s=1.23456709876543 (true sum) e=5; s=1.234567 (after rounding and normalization)

In the above conceptual examples it would appear that a large number of extra digits would need to be provided by the adder to ensure correct rounding; however, for binary addition or subtraction using careful implementation techniques only a guard bit, a rounding bit and one extra sticky bit need to be carried beyond the precision of the operands.[18][44]: 218–220

Another problem of loss of significance occurs when approximations to two nearly equal numbers are subtracted. In the following example e = 5; s = 1.234571 and e = 5; s = 1.234567 are approximations to the rationals 123457.1467 and 123456.659.

e=5; s=1.234571 − e=5; s=1.234567 ---------------- e=5; s=0.000004 e=−1; s=4.000000 (after rounding and normalization)

The floating-point difference is computed exactly because the numbers are close—the Sterbenz lemma guarantees this, even in case of underflow when gradual underflow is supported. Despite this, the difference of the original numbers is e = −1; s = 4.877000, which differs more than 20% from the difference e = −1; s = 4.000000 of the approximations. In extreme cases, all significant digits of precision can be lost.[18][45] This cancellation illustrates the danger in assuming that all of the digits of a computed result are meaningful. Dealing with the consequences of these errors is a topic in numerical analysis; see also Accuracy problems.

Multiplication and division

[edit]To multiply, the significands are multiplied while the exponents are added, and the result is rounded and normalized.

e=3; s=4.734612 × e=5; s=5.417242 ----------------------- e=8; s=25.648538980104 (true product) e=8; s=25.64854 (after rounding) e=9; s=2.564854 (after normalization)

Similarly, division is accomplished by subtracting the divisor's exponent from the dividend's exponent, and dividing the dividend's significand by the divisor's significand.

There are no cancellation or absorption problems with multiplication or division, though small errors may accumulate as operations are performed in succession.[18] In practice, the way these operations are carried out in digital logic can be quite complex (see Booth's multiplication algorithm and Division algorithm).[nb 9]

Literal syntax

[edit]Literals for floating-point numbers depend on languages. They typically use e or E to denote scientific notation. The C programming language and the IEEE 754 standard also define a hexadecimal literal syntax with a base-2 exponent instead of 10. In languages like C, when the decimal exponent is omitted, a decimal point is needed to differentiate them from integers. Other languages do not have an integer type (such as JavaScript), or allow overloading of numeric types (such as Haskell). In these cases, digit strings such as 123 may also be floating-point literals.

Examples of floating-point literals are:

99.9-5000.126.02e23-3e-450x1.fffffep+127in C and IEEE 754

Dealing with exceptional cases

[edit]Floating-point computation in a computer can run into three kinds of problems:

- An operation can be mathematically undefined, such as ∞/∞, or division by zero.

- An operation can be legal in principle, but not supported by the specific format, for example, calculating the square root of −1 or the inverse sine of 2 (both of which result in complex numbers).

- An operation can be legal in principle, but the result can be impossible to represent in the specified format, because the exponent is too large or too small to encode in the exponent field. Such an event is called an overflow (exponent too large), underflow (exponent too small) or denormalization (precision loss).

Prior to the IEEE standard, such conditions usually caused the program to terminate, or triggered some kind of trap that the programmer might be able to catch. How this worked was system-dependent, meaning that floating-point programs were not portable. (The term "exception" as used in IEEE 754 is a general term meaning an exceptional condition, which is not necessarily an error, and is a different usage to that typically defined in programming languages such as a C++ or Java, in which an "exception" is an alternative flow of control, closer to what is termed a "trap" in IEEE 754 terminology.)

Here, the required default method of handling exceptions according to IEEE 754 is discussed (the IEEE 754 optional trapping and other "alternate exception handling" modes are not discussed). Arithmetic exceptions are (by default) required to be recorded in "sticky" status flag bits. That they are "sticky" means that they are not reset by the next (arithmetic) operation, but stay set until explicitly reset. The use of "sticky" flags thus allows for testing of exceptional conditions to be delayed until after a full floating-point expression or subroutine: without them exceptional conditions that could not be otherwise ignored would require explicit testing immediately after every floating-point operation. By default, an operation always returns a result according to specification without interrupting computation. For instance, 1/0 returns +∞, while also setting the divide-by-zero flag bit (this default of ∞ is designed to often return a finite result when used in subsequent operations and so be safely ignored).

The original IEEE 754 standard, however, failed to recommend operations to handle such sets of arithmetic exception flag bits. So while these were implemented in hardware, initially programming language implementations typically did not provide a means to access them (apart from assembler). Over time some programming language standards (e.g., C99/C11 and Fortran) have been updated to specify methods to access and change status flag bits. The 2008 version of the IEEE 754 standard now specifies a few operations for accessing and handling the arithmetic flag bits. The programming model is based on a single thread of execution and use of them by multiple threads has to be handled by a means outside of the standard (e.g. C11 specifies that the flags have thread-local storage).

IEEE 754 specifies five arithmetic exceptions that are to be recorded in the status flags ("sticky bits"):

- inexact, set if the rounded (and returned) value is different from the mathematically exact result of the operation.

- underflow, set if the rounded value is tiny (as specified in IEEE 754) and inexact (or maybe limited to if it has denormalization loss, as per the 1985 version of IEEE 754), returning a subnormal value including the zeros.

- overflow, set if the absolute value of the rounded value is too large to be represented. An infinity or maximal finite value is returned, depending on which rounding is used.

- divide-by-zero, set if the result is infinite given finite operands, returning an infinity, either +∞ or −∞.

- invalid, set if a finite or infinite result cannot be returned e.g. sqrt(−1) or 0/0, returning a quiet NaN.

The default return value for each of the exceptions is designed to give the correct result in the majority of cases such that the exceptions can be ignored in the majority of codes. inexact returns a correctly rounded result, and underflow returns a value less than or equal to the smallest positive normal number in magnitude and can almost always be ignored.[46] divide-by-zero returns infinity exactly, which will typically then divide a finite number and so give zero, or else will give an invalid exception subsequently if not, and so can also typically be ignored. For example, the effective resistance of n resistors in parallel (see fig. 1) is given by . If a short-circuit develops with set to 0, will return +infinity which will give a final of 0, as expected[47] (see the continued fraction example of IEEE 754 design rationale for another example).

Overflow and invalid exceptions can typically not be ignored, but do not necessarily represent errors: for example, a root-finding routine, as part of its normal operation, may evaluate a passed-in function at values outside of its domain, returning NaN and an invalid exception flag to be ignored until finding a useful start point.[46]

Accuracy problems

[edit]The fact that floating-point numbers cannot accurately represent all real numbers, and that floating-point operations cannot accurately represent true arithmetic operations, leads to many surprising situations. This is related to the finite precision with which computers generally represent numbers.

For example, the decimal numbers 0.1 and 0.01 cannot be represented exactly as binary floating-point numbers. In the IEEE 754 binary32 format with its 24-bit significand, the result of attempting to square the approximation to 0.1 is neither 0.01 nor the representable number closest to it. The decimal number 0.1 is represented in binary as e = −4; s = 110011001100110011001101, which is

Squaring this number gives

Squaring it with rounding to the 24-bit precision gives

But the representable number closest to 0.01 is

Also, the non-representability of π (and π/2) means that an attempted computation of tan(π/2) will not yield a result of infinity, nor will it even overflow in the usual floating-point formats (assuming an accurate implementation of tan). It is simply not possible for standard floating-point hardware to attempt to compute tan(π/2), because π/2 cannot be represented exactly. This computation in C:

// Enough digits to be sure we get the correct approximation.

const double pi = 3.1415926535897932384626433832795;

double z = tan(pi / 2.0);

will give a result of 16331239353195370.0. In single precision (using the tanf function), the result will be −22877332.0.

By the same token, an attempted computation of sin(π) will not yield zero. The result will be (approximately) 0.1225×10−15 in double precision, or −0.8742×10−7 in single precision.[nb 10]

While floating-point addition and multiplication are both commutative (a + b = b + a and a × b = b × a), they are not necessarily associative. That is, (a + b) + c is not necessarily equal to a + (b + c). Using 7-digit significand decimal arithmetic:

a = 1234.567, b = 45.67834, c = 0.0004

(a + b) + c:

1234.567 (a)

+ 45.67834 (b)

____________

1280.24534 rounds to 1280.245

1280.245 (a + b)

+ 0.0004 (c)

____________

1280.2454 rounds to 1280.245 ← (a + b) + c

a + (b + c): 45.67834 (b) + 0.0004 (c) ____________ 45.67874

1234.567 (a) + 45.67874 (b + c) ____________ 1280.24574 rounds to 1280.246 ← a + (b + c)

They are also not necessarily distributive. That is, (a + b) × c may not be the same as a × c + b × c:

1234.567 × 3.333333 = 4115.223

1.234567 × 3.333333 = 4.115223

4115.223 + 4.115223 = 4119.338

but

1234.567 + 1.234567 = 1235.802

1235.802 × 3.333333 = 4119.340

In addition to loss of significance, inability to represent numbers such as π and 0.1 exactly, and other slight inaccuracies, the following phenomena may occur:

- Cancellation: subtraction of nearly equal operands may cause extreme loss of accuracy.[48][45] When we subtract two almost equal numbers we set the most significant digits to zero, leaving ourselves with just the insignificant, and most erroneous, digits.[1]: 124 For example, when determining a derivative of a function the following formula is used:

Intuitively one would want an h very close to zero; however, when using floating-point operations, the smallest number will not give the best approximation of a derivative. As h grows smaller, the difference between f(a + h) and f(a) grows smaller, cancelling out the most significant and least erroneous digits and making the most erroneous digits more important. As a result the smallest number of h possible will give a more erroneous approximation of a derivative than a somewhat larger number. This is perhaps the most common and serious accuracy problem. - Conversions to integer are not intuitive: converting (63.0/9.0) to integer yields 7, but converting (0.63/0.09) may yield 6. This is because conversions generally truncate rather than round. Floor and ceiling functions may produce answers which are off by one from the intuitively expected value.

- Limited exponent range: results might overflow yielding infinity, or underflow yielding a subnormal number or zero. In these cases precision will be lost.

- Testing for safe division is problematic: Checking that the divisor is not zero does not guarantee that a division will not overflow.

- Testing for equality is problematic. Two computational sequences that are mathematically equal may well produce different floating-point values.[49]

Incidents

[edit]- On 25 February 1991, a loss of significance in a MIM-104 Patriot missile battery prevented it from intercepting an incoming Scud missile in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, contributing to the death of 28 soldiers from the U.S. Army's 14th Quartermaster Detachment.[50] The weapons control computer counted time in an integer number of tenths of a second since boot. For conversion to a floating-point number of seconds in velocity and position calculations, the software originally multiplied this number by a 24-bit fixed-point binary approximation to 0.1, specifically Some parts of the software were later adapted to use a more accurate conversion to floating-point, but some parts were not updated and still used the 24-bit approximation.[51] These parts of the software drifted from one another by about 3.43 milliseconds per hour. After 20 hours, the discrepancy of about 68.7 ms was enough for the radar tracking system to lose track of Scuds; the control system in the Dhahran missile battery had been running for about 100 hours when it failed to track and intercept an incoming Scud.[50] The failure to intercept arose not from using floating point specifically, but from subtracting two different approximations to unit conversion with different errors when representing time, so the unit conversion error in the difference did not cancel out but rather grew indefinitely with uptime.[51]

- Salami slicing is the practice of removing the 'invisible' part of a transaction into a separate account.[clarification needed]

Machine precision and backward error analysis

[edit]Machine precision is a quantity that characterizes the accuracy of a floating-point system, and is used in backward error analysis of floating-point algorithms. It is also known as unit roundoff or machine epsilon. Usually denoted Εmach, its value depends on the particular rounding being used.

With rounding to zero, whereas rounding to nearest, where B is the base of the system and P is the precision of the significand (in base B).

This is important since it bounds the relative error in representing any non-zero real number x within the normalized range of a floating-point system:

Backward error analysis, the theory of which was developed and popularized by James H. Wilkinson, can be used to establish that an algorithm implementing a numerical function is numerically stable.[52] The basic approach is to show that although the calculated result, due to roundoff errors, will not be exactly correct, it is the exact solution to a nearby problem with slightly perturbed input data. If the perturbation required is small, on the order of the uncertainty in the input data, then the results are in some sense as accurate as the data "deserves". The algorithm is then defined as backward stable. Stability is a measure of the sensitivity to rounding errors of a given numerical procedure; by contrast, the condition number of a function for a given problem indicates the inherent sensitivity of the function to small perturbations in its input and is independent of the implementation used to solve the problem.[53]

As a trivial example, consider a simple expression giving the inner product of (length two) vectors and , then and so

where

where

by definition, which is the sum of two slightly perturbed (on the order of Εmach) input data, and so is backward stable. For more realistic examples in numerical linear algebra, see Higham 2002[54] and other references below.

Minimizing the effect of accuracy problems

[edit]Although individual arithmetic operations of IEEE 754 are guaranteed accurate to within half a ULP, more complicated formulae can suffer from larger errors for a variety of reasons. The loss of accuracy can be substantial if a problem or its data are ill-conditioned, meaning that the correct result is hypersensitive to tiny perturbations in its data. However, even functions that are well-conditioned can suffer from large loss of accuracy if an algorithm numerically unstable for that data is used: apparently equivalent formulations of expressions in a programming language can differ markedly in their numerical stability. One approach to remove the risk of such loss of accuracy is the design and analysis of numerically stable algorithms, which is an aim of the branch of mathematics known as numerical analysis. Another approach that can protect against the risk of numerical instabilities is the computation of intermediate (scratch) values in an algorithm at a higher precision than the final result requires,[55] which can remove, or reduce by orders of magnitude,[56] such risk: IEEE 754 quadruple precision and extended precision are designed for this purpose when computing at double precision.[57][nb 11]

For example, the following algorithm is a direct implementation to compute the function , which is well-conditioned at .[nb 12] However, it can be shown to be numerically unstable and lose up to half the significant digits carried by the arithmetic when computed near 1.0.[58]

#include <math.h>

double f(double x)

{

double y = x - 1.0;

double z = exp(y);

if (z != 1.0) {

z = y / (z - 1.0);

}

return z;

}

A numerical analysis of the algorithm reveals that if the following non-obvious change to the line z = y / (z - 1.0); is made:

z = log(z) / (z - 1.0);

then the algorithm becomes numerically stable and can compute to full double precision.[58]

To maintain the properties of such carefully constructed numerically stable programs, careful handling by the compiler is required. Certain "optimizations" that compilers might make (for example, reordering operations) can work against the goals of well-behaved software. There is some controversy about the failings of compilers and language designs in this area: C99 is an example of a language where such optimizations are carefully specified to maintain numerical precision. See the external references at the bottom of this article.

A detailed treatment of the techniques for writing high-quality floating-point software is beyond the scope of this article, and the reader is referred to,[54][59] and the other references at the bottom of this article. Kahan suggests several rules of thumb that can substantially decrease by orders of magnitude[59] the risk of numerical anomalies, in addition to, or in lieu of, a more careful numerical analysis. These include: as noted above, computing all expressions and intermediate results in the highest precision supported in hardware (a common rule of thumb is to carry twice the precision of the desired result, i.e. compute in double precision for a final single-precision result, or in double extended or quad precision for up to double-precision results[60]); and rounding input data and results to only the precision required and supported by the input data (carrying excess precision in the final result beyond that required and supported by the input data can be misleading, increases storage cost and decreases speed, and the excess bits can affect convergence of numerical procedures:[61] notably, the first form of the iterative example given below converges correctly when using this rule of thumb). Brief descriptions of several additional issues and techniques follow.

As decimal fractions can often not be exactly represented in binary floating-point, such arithmetic is at its best when it is simply being used to measure real-world quantities over a wide range of scales (such as the orbital period of a moon around Saturn or the mass of a proton), and at its worst when it is expected to model the interactions of quantities expressed as decimal strings that are expected to be exact.[56][59] An example of the latter case is financial calculations. For this reason, financial software tends not to use a binary floating-point number representation.[62] The "decimal" data type of the C# and Python programming languages, and the decimal formats of the IEEE 754-2008 standard, are designed to avoid the problems of binary floating-point representations when applied to human-entered exact decimal values, and make the arithmetic always behave as expected when numbers are printed in decimal.

Expectations from mathematics may not be realized in the field of floating-point computation. For example, it is known that , and that . However, these facts cannot be relied on when the quantities involved are the result of floating-point computation.

The use of the equality test (if (x==y) ...) requires care when dealing with floating-point numbers. Even simple expressions like 0.6 / 0.2 - 3 == 0 will, on most computers, fail to be true[63] (in IEEE 754 double precision, for example, 0.6 / 0.2 - 3 is approximately equal to −4.44089209850063×10−16). Consequently, such tests are sometimes replaced with "fuzzy" comparisons (if (abs(x-y) < epsilon) ..., where epsilon is sufficiently small and tailored to the application, such as 1.0E−13). The wisdom of doing this varies greatly, and can require numerical analysis to bound epsilon.[54] Values derived from the primary data representation and their comparisons should be performed in a wider, extended, precision to minimize the risk of such inconsistencies due to round-off errors.[59] It is often better to organize the code in such a way that such tests are unnecessary. For example, in computational geometry, exact tests of whether a point lies off or on a line or plane defined by other points can be performed using adaptive precision or exact arithmetic methods.[64]

Small errors in floating-point arithmetic can grow when mathematical algorithms perform operations an enormous number of times. A few examples are matrix inversion, eigenvector computation, and differential equation solving. These algorithms must be very carefully designed, using numerical approaches such as iterative refinement, if they are to work well.[65]

Summation of a vector of floating-point values is a basic algorithm in scientific computing, and so an awareness of when loss of significance can occur is essential. For example, if one is adding a very large number of numbers, the individual addends are very small compared with the sum. This can lead to loss of significance. A typical addition would then be something like

3253.671 + 3.141276 ----------- 3256.812

The low 3 digits of the addends are effectively lost. Suppose, for example, that one needs to add many numbers, all approximately equal to 3. After 1000 of them have been added, the running sum is about 3000; the lost digits are not regained. The Kahan summation algorithm may be used to reduce the errors.[54]

Round-off error can affect the convergence and accuracy of iterative numerical procedures. As an example, Archimedes approximated π by calculating the perimeters of polygons inscribing and circumscribing a circle, starting with hexagons, and successively doubling the number of sides. As noted above, computations may be rearranged in a way that is mathematically equivalent but less prone to error (numerical analysis). Two forms of the recurrence formula for the circumscribed polygon are:[citation needed]

- First form:

- Second form:

- , converging as

Here is a computation using IEEE "double" (a significand with 53 bits of precision) arithmetic:

i 6 × 2i × ti, first form 6 × 2i × ti, second form --------------------------------------------------------- 0 3.4641016151377543863 3.4641016151377543863 1 3.2153903091734710173 3.2153903091734723496 2 3.1596599420974940120 3.1596599420975006733 3 3.1460862151314012979 3.1460862151314352708 4 3.1427145996453136334 3.1427145996453689225 5 3.1418730499801259536 3.1418730499798241950 6 3.1416627470548084133 3.1416627470568494473 7 3.1416101765997805905 3.1416101766046906629 8 3.1415970343230776862 3.1415970343215275928 9 3.1415937488171150615 3.1415937487713536668 10 3.1415929278733740748 3.1415929273850979885 11 3.1415927256228504127 3.1415927220386148377 12 3.1415926717412858693 3.1415926707019992125 13 3.1415926189011456060 3.1415926578678454728 14 3.1415926717412858693 3.1415926546593073709 15 3.1415919358822321783 3.1415926538571730119 16 3.1415926717412858693 3.1415926536566394222 17 3.1415810075796233302 3.1415926536065061913 18 3.1415926717412858693 3.1415926535939728836 19 3.1414061547378810956 3.1415926535908393901 20 3.1405434924008406305 3.1415926535900560168 21 3.1400068646912273617 3.1415926535898608396 22 3.1349453756585929919 3.1415926535898122118 23 3.1400068646912273617 3.1415926535897995552 24 3.2245152435345525443 3.1415926535897968907 25 3.1415926535897962246 26 3.1415926535897962246 27 3.1415926535897962246 28 3.1415926535897962246 The true value is 3.14159265358979323846264338327...

While the two forms of the recurrence formula are clearly mathematically equivalent,[nb 13] the first subtracts 1 from a number extremely close to 1, leading to an increasingly problematic loss of significant digits. As the recurrence is applied repeatedly, the accuracy improves at first, but then it deteriorates. It never gets better than about 8 digits, even though 53-bit arithmetic should be capable of about 16 digits of precision. When the second form of the recurrence is used, the value converges to 15 digits of precision.

"Fast math" optimization

[edit]The aforementioned lack of associativity of floating-point operations in general means that compilers cannot as effectively reorder arithmetic expressions as they could with integer and fixed-point arithmetic, presenting a roadblock in optimizations such as common subexpression elimination and auto-vectorization.[66] The "fast math" option on many compilers (ICC, GCC, Clang, MSVC...) turns on reassociation along with unsafe assumptions such as a lack of NaN and infinite numbers in IEEE 754. Some compilers also offer more granular options to only turn on reassociation. In either case, the programmer is exposed to many of the precision pitfalls mentioned above for the portion of the program using "fast" math.[67]

In some compilers (GCC and Clang), turning on "fast" math may cause the program to disable subnormal floats at startup, affecting the floating-point behavior of not only the generated code, but also any program using such code as a library.[68]

In most Fortran compilers, as allowed by the ISO/IEC 1539-1:2004 Fortran standard, reassociation is the default, with breakage largely prevented by the "protect parens" setting (also on by default). This setting stops the compiler from reassociating beyond the boundaries of parentheses.[69] Intel Fortran Compiler is a notable outlier.[70]

A common problem in "fast" math is that subexpressions may not be optimized identically from place to place, leading to unexpected differences. One interpretation of the issue is that "fast" math as implemented currently has a poorly defined semantics. One attempt at formalizing "fast" math optimizations is seen in Icing, a verified compiler.[71]

See also

[edit]- Arbitrary-precision arithmetic

- C99 for code examples demonstrating access and use of IEEE 754 features.

- Computable number

- Coprocessor

- Decimal floating point

- Double-precision floating-point format

- Experimental mathematics – utilizes high precision floating-point computations

- Fixed-point arithmetic

- Floating-point error mitigation

- FLOPS

- Gal's accurate tables

- GNU MPFR

- Half-precision floating-point format

- IEEE 754 – Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic

- IBM Floating Point Architecture

- Kahan summation algorithm

- Microsoft Binary Format (MBF)

- Minifloat

- Q (number format) for constant resolution

- Quadruple-precision floating-point format (including double-double)

- Significant figures

- Single-precision floating-point format

- Standard Apple Numerics Environment (SANE)

Notes

[edit]- ^ The significand of a floating-point number is also called mantissa by some authors—not to be confused with the mantissa of a logarithm. Somewhat vague, terms such as coefficient or argument are also used by some. The usage of the term fraction by some authors is potentially misleading as well. The term characteristic (as used e.g. by CDC) is ambiguous, as it was historically also used to specify some form of exponent of floating-point numbers.

- ^ The exponent of a floating-point number is sometimes also referred to as scale. The term characteristic (for biased exponent, exponent bias, or excess n representation) is ambiguous, as it was historically also used to specify the significand of floating-point numbers.

- ^ Hexadecimal (base-16) floating-point arithmetic is used in the IBM System 360 (1964) and 370 (1970) as well as various newer IBM machines, in the RCA Spectra 70 (1964), the Siemens 4004 (1965), 7.700 (1974), 7.800, 7.500 (1977) series mainframes and successors, the Unidata 7.000 series mainframes, the Manchester MU5 (1972), the HEP (1982) computers, and in 360/370-compatible mainframe families made by Fujitsu, Amdahl and Hitachi. It is also used in the Illinois ILLIAC III (1966), Data General Eclipse S/200 (ca. 1974), Gould Powernode 9080 (1980s), Interdata 8/32 (1970s), the SEL Systems 85 and 86 as well as the SDS Sigma 5 (1967), 7 (1966) and Xerox Sigma 9 (1970).

- ^ Octal (base-8) floating-point arithmetic is used in the Ferranti Atlas (1962), Burroughs B5500 (1964), Burroughs B5700 (1971), Burroughs B6700 (1971) and Burroughs B7700 (1972) computers.

- ^ Quaternary (base-4) floating-point arithmetic is used in the Illinois ILLIAC II (1962) computer. It is also used in the Digital Field System DFS IV and V high-resolution site survey systems.

- ^ Base-256 floating-point arithmetic is used in the Rice Institute R1 computer (since 1958).

- ^ Base-65536 floating-point arithmetic is used in the MANIAC II (1956) computer.

- ^ Computer hardware does not necessarily compute the exact value; it simply has to produce the equivalent rounded result as though it had computed the infinitely precise result.

- ^ The enormous complexity of modern division algorithms once led to a famous error. An early version of the Intel Pentium chip was shipped with a division instruction that, on rare occasions, gave slightly incorrect results. Many computers had been shipped before the error was discovered. Until the defective computers were replaced, patched versions of compilers were developed that could avoid the failing cases. See Pentium FDIV bug.

- ^ But an attempted computation of yields exactly. Since the derivative is nearly zero near , the effect of the inaccuracy in the argument is far smaller than the spacing of the floating-point numbers around , and the rounded result is exact.

- ^ William Kahan notes: "Except in extremely uncommon situations, extra-precise arithmetic generally attenuates risks due to roundoff at far less cost than the price of a competent error-analyst."

- ^ The Taylor expansion of this function demonstrates that it is well-conditioned near : for .

- ^ The equivalence of the two forms can be verified algebraically by noting that the denominator of the fraction in the second form is the conjugate of the numerator of the first. By multiplying the top and bottom of the first expression by this conjugate, one obtains the second expression.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Muller, Jean-Michel; Brisebarre, Nicolas; de Dinechin, Florent; Jeannerod, Claude-Pierre; Lefèvre, Vincent; Melquiond, Guillaume; Revol, Nathalie; Stehlé, Damien; Torres, Serge (2010). Handbook of Floating-Point Arithmetic (1st ed.). Birkhäuser. doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-4705-6. ISBN 978-0-8176-4704-9. LCCN 2009939668.

- ^ a b Sterbenz, Pat H. (1974). Floating-Point Computation. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, United States: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-322495-3.

- ^ Smith, Steven W. (1997). "Chapter 28, Fixed versus Floating Point". The Scientist and Engineer's Guide to Digital Signal Processing. California Technical Pub. p. 514. ISBN 978-0-9660176-3-2. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ a b Zehendner, Eberhard (Summer 2008). "Rechnerarithmetik: Fest- und Gleitkommasysteme" (PDF) (Lecture script) (in German). Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2018-08-07. [1] (NB. This reference incorrectly gives the MANIAC II's floating point base as 256, whereas it actually is 65536.)

- ^ a b c d Beebe, Nelson H. F. (2017-08-22). "Chapter H. Historical floating-point architectures". The Mathematical-Function Computation Handbook - Programming Using the MathCW Portable Software Library (1st ed.). Salt Lake City, UT, USA: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 948. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64110-2. ISBN 978-3-319-64109-6. LCCN 2017947446. S2CID 30244721.

- ^ Savard, John J. G. (2018) [2007], "The Decimal Floating-Point Standard", quadibloc, archived from the original on 2018-07-03, retrieved 2018-07-16

- ^ Parkinson, Roger (2000-12-07). "Chapter 2 - High resolution digital site survey systems - Chapter 2.1 - Digital field recording systems". High Resolution Site Surveys (1st ed.). CRC Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-20318604-6. Retrieved 2019-08-18.

[…] Systems such as the [Digital Field System] DFS IV and DFS V were quaternary floating-point systems and used gain steps of 12 dB. […]

(256 pages) - ^ Lazarus, Roger B. (1957-01-30) [1956-10-01]. "MANIAC II" (PDF). Los Alamos, NM, USA: Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory of the University of California. p. 14. LA-2083. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2018-08-07.

[…] the Maniac's floating base, which is 216 = 65,536. […] The Maniac's large base permits a considerable increase in the speed of floating point arithmetic. Although such a large base implies the possibility of as many as 15 lead zeros, the large word size of 48 bits guarantees adequate significance. […]

- ^ Torres Quevedo, Leonardo. Automática: Complemento de la Teoría de las Máquinas, (pdf), pp. 575–583, Revista de Obras Públicas, 19 November 1914.

- ^ Ronald T. Kneusel. Numbers and Computers, Springer, pp. 84–85, 2017. ISBN 978-3319505084

- ^ Randell 1982, pp. 6, 11–13.

- ^ Randell, Brian. Digital Computers, History of Origins, (pdf), p. 545, Digital Computers: Origins, Encyclopedia of Computer Science, January 2003.

- ^ Rojas, Raúl (April–June 1997). "Konrad Zuse's Legacy: The Architecture of the Z1 and Z3" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 19 (2): 5–16. doi:10.1109/85.586067. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-07-03. Retrieved 2022-07-03. (12 pages)

- ^ Rojas, Raúl (2014-06-07). "The Z1: Architecture and Algorithms of Konrad Zuse's First Computer". arXiv:1406.1886 [cs.AR].

- ^ a b Kahan, William Morton (1997-07-15). "The Baleful Effect of Computer Languages and Benchmarks upon Applied Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry. John von Neumann Lecture" (PDF). p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-05.

- ^ Randell, Brian, ed. (1982) [1973]. The Origins of Digital Computers: Selected Papers (3rd ed.). Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 244. ISBN 978-3-540-11319-5.

- ^ Severance, Charles (1998-02-20). "An Interview with the Old Man of Floating-Point".

- ^ a b c d Goldberg, David (March 1991). "What Every Computer Scientist Should Know About Floating-Point Arithmetic". ACM Computing Surveys. 23 (1): 5–48. doi:10.1145/103162.103163. S2CID 222008826. (With the addendum "Differences Among IEEE 754 Implementations": [2], [3])

- ^ ISO/IEC 9899:1999 - Programming languages - C. Iso.org. §F.2, note 307.

"Extended" is IEC 60559's double-extended data format. Extended refers to both the common 80-bit and quadruple 128-bit IEC 60559 formats.

- ^ "IEEE Floating-Point Representation". 2021-08-03.

- ^ Using the GNU Compiler Collection, i386 and x86-64 Options Archived 2015-01-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "long double (GCC specific) and __float128". StackOverflow.

- ^ "Procedure Call Standard for the ARM 64-bit Architecture (AArch64)" (PDF). 2013-05-22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-07-31. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- ^ "ARM Compiler toolchain Compiler Reference, Version 5.03" (PDF). 2013. Section 6.3 Basic data types. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-27. Retrieved 2019-11-08.

- ^ Kahan, William Morton (2004-11-20). "On the Cost of Floating-Point Computation Without Extra-Precise Arithmetic" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-05-25. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- ^ "openEXR". openEXR. Archived from the original on 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

Since the IEEE-754 floating-point specification does not define a 16-bit format, ILM created the "half" format. Half values have 1 sign bit, 5 exponent bits, and 10 mantissa bits.

- ^ "Technical Introduction to OpenEXR – The half Data Type". openEXR. Retrieved 2024-04-16.

- ^ "IEEE-754 Analysis". Retrieved 2024-08-29.

- ^ a b Borland staff (1998-07-02) [1994-03-10]. "Converting between Microsoft Binary and IEEE formats". Technical Information Database (TI1431C.txt). Embarcadero USA / Inprise (originally: Borland). ID 1400. Archived from the original on 2019-02-20. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

[…] _fmsbintoieee(float *src4, float *dest4) […] MS Binary Format […] byte order => m3 | m2 | m1 | exponent […] m1 is most significant byte => sbbb|bbbb […] m3 is the least significant byte […] m = mantissa byte […] s = sign bit […] b = bit […] MBF is bias 128 and IEEE is bias 127. […] MBF places the decimal point before the assumed bit, while IEEE places the decimal point after the assumed bit. […] ieee_exp = msbin[3] - 2; /* actually, msbin[3]-1-128+127 */ […] _dmsbintoieee(double *src8, double *dest8) […] MS Binary Format […] byte order => m7 | m6 | m5 | m4 | m3 | m2 | m1 | exponent […] m1 is most significant byte => smmm|mmmm […] m7 is the least significant byte […] MBF is bias 128 and IEEE is bias 1023. […] MBF places the decimal point before the assumed bit, while IEEE places the decimal point after the assumed bit. […] ieee_exp = msbin[7] - 128 - 1 + 1023; […]