Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Desktop search

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Desktop search tools search within a user's own computer files as opposed to searching the Internet. These tools are designed to find information on the user's PC, including web browser history, e-mail archives, text documents, sound files, images, and video. A variety of desktop search programs are now available; see this list for examples. Most desktop search programs are standalone applications. Desktop search products are software alternatives to the search software included in the operating system, helping users sift through desktop files, emails, attachments, and more.[1][2][3]

Desktop search emerged as a concern for large firms for two main reasons: untapped productivity and security. According to analyst firm Gartner, up to 80% of some companies' data is locked up inside unstructured data — the information stored on a user's PC, the directories (folders) and files they've created on a network, documents stored in repositories such as corporate intranets and a multitude of other locations.[4] Moreover, many companies have structured or unstructured information stored in older file formats to which they don't have ready access.

The sector attracted considerable attention in the late 2004 to early 2005 period from the struggle between Microsoft and Google.[5][6][7] According to market analysts, both companies were attempting to leverage their monopolies (of web browsers and search engines, respectively) to strengthen their dominance. Due to Google's complaint that users of Windows Vista cannot choose any competitor's desktop search program over the built-in one, an agreement was reached between US Justice Department and Microsoft that Windows Vista Service Pack 1 would enable users to choose between the built-in and other desktop search programs, and select which one is to be the default.[8] As of September 2011, Google ended life for Google Desktop.

Technologies

[edit]Most desktop search engines build and maintain an index database to improve performance when searching large amounts of data. Indexing usually takes place when the computer is idle and most search applications can be set to suspend indexing if a portable computer is running on batteries, in order to save power. There are notable exceptions, however: Voidtools' Everything Search Engine,[9] which performs searches over only file names, not contents, is able to build its index from scratch in just a few seconds. Another exception is Vegnos Desktop Search Engine,[10] which performs searches over filenames and files' contents without building any indices. An index may also not be up-to-date, when a query is performed. In this case, results returned will not be accurate (that is, a hit may be shown when it is no longer there, and a file may not be shown, when in fact it is a hit). Some products have sought to remedy this disadvantage by building a real-time indexing function into the software. There are disadvantages to not indexing. Namely, the time to complete a query can be significant, and the issued query can also be resource-intensive.

Desktop search tools typically collect three types of information about files:

- file and folder names

- metadata, such as titles, authors, comments in file types such as MP3, PDF and JPEG

- file content, for the types of documents supported by the tool

Long-term goals for desktop search include the ability to search the contents of image files, sound files and video by context.[11][12]

Platforms & their histories

[edit]Windows

[edit]

Indexing Service, a "base service that extracts content from files and constructs an indexed catalog to facilitate efficient and rapid searching",[13] was originally released in August 1996. It was built in order to speed up manually searching for files on Personal Desktops and Corporate Computer Network. Indexing service helped by using Microsoft web servers to index files on the desired hard drives. Indexing was done by file format. By using terms that users provided, a search was conducted that matched terms to the data within the file formats. The largest issue that Indexing service faced was that every time a file was added, it had to be indexed. This coupled with the fact that the indexing cached the entire index in RAM, made the hardware a huge limitation.[14] This made indexing large amounts of files require extremely powerful hardware and very long wait times.

In 2003, Windows Desktop Search (WDS) replaced Microsoft Indexing Service. Instead of only matching terms to the details of the file format and file names, WDS brings in content indexing to all Microsoft files and text-based formats such as e-mail and text files. This means, that WDS looked into the files and indexed the content. Thus, when a user searched a term, WDS no longer matched just information such as file format types and file names, but terms, and values stored within those files. WDS also brought "Instant searching" meaning the user could type a character and the query would instantly start searching and updating the query as the user typed in more characters.[15] Windows Search apparently used up a lot of processing power, as Windows Desktop Search would only run if it was directly queried or while the PC was idle. Even only running while directly queried or while the computer was idled, indexing the entire hard drive still took hours. The index would be around 10% of the size of all the files that it indexed, e.g. if the indexed files amounted to around 100GB, the index size would be 10GB.

With the release of Windows Vista came Windows Search 3.1. Unlike its predecessors WDS and Windows Search 3.0, 3.1 could search through both indexed and non indexed locations seamlessly. Also, the RAM and CPU requirements were greatly reduced, cutting back indexing times immensely. Windows Search 4.0 is currently running on all PCs with Windows 7 and up.

Mac OS

[edit]In 1994 the AppleSearch search engine was introduced, allowing users to fully search all documents within their Macintosh computer, including file format types, meta-data on those files, and content within the files. AppleSearch was a client/server application, and as such required a server separate from the main device in order to function. The biggest issue with AppleSearch were its large resource requirements: "AppleSearch requires at least a 68040 processor and 5MB of RAM."[16] At the time, a Macintosh computer with these specifications was priced at approximately $1400; equivalent to $2050 in 2015.[17] On top of this, the software itself cost an additional $1400 for a single license.

In 1997, Sherlock was released alongside Mac OS 8.5. Sherlock (named after the famous fictional detective Sherlock Holmes) was integrated into Mac OS's file browser – Finder. Sherlock extended the desktop search function to the World Wide Web, allowing users to search both locally and externally. Adding additional functions—such as internet access—to Sherlock was relatively simple, as this was done through plugins written as plain text files. Sherlock was included in every release of Mac OS from Mac OS 8, before being deprecated and replaced by Spotlight and Dashboard in Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger. It was officially removed in Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard

Spotlight was released in 2005 as part of Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger. It is a Selection-based search tool, which means the user invokes a query using only the mouse. Spotlight allows the user to search the Internet for more information about any keyword or phrase contained within a document or webpage, and uses a built-in calculator and Oxford American Dictionary to offer quick access to small calculations and word definitions.[18] While Spotlight initially has a long startup time, this decreases as the hard disk is indexed. As files are added by the user, the index is constantly updated in the background using minimal CPU & RAM resources.

Linux

[edit]There are a wide range of desktop search options for Linux users, depending upon the skill level of the user, their preference to use desktop tools which tightly integrate into their desktop environment, command-shell functionality (often with advanced scripting options), or browser-based users interfaces to locally running software. In addition, many users create their own indexing from a variety of indexing packages (e.g. one which does extraction and indexing of PDF/DOC/DOCX/ODT documents well, another search engine which works ith/ vcard, LDAP, and other directory/contact databases, as well as the conventional find and locate commands.

Ubuntu

[edit]

Ubuntu Linux didn't have desktop search until release Feisty Fawn 7.04. Using Tracker[19] desktop search, the desktop search feature was very similar to Mac OS's AppleSearch and Sherlock. It not only featured the basic features of file format sorting and meta-data matching, but support for searching through emails and instant messages was added. In 2014 Recoll[20] was added to Linux distributions, working with other search programs such as Tracker and Beagle to provide efficient full text search. This greatly increased the types of queries and file types that Linux desktop searches could handle. A major advantage of Recoll is that it allows for greater customization of what is indexed; Recoll will index the entire hard disk by default, but can be made to index only selected directories, omitting directories that will never need to be searched.[21]

openSUSE

[edit]In openSUSE, starting with KDE4, the NEPOMUK was introduced. It provided the ability to index a wide range of desktop content, email, and use semantic web technologies (e.g. RDF) to annotate the database. The introduction faced a few glitches, much of which seemed to be based on the triplestore. Performance improved (at least for queries) by switching the backend to a stripped-down version of the Virtuoso Open Source Edition, however indexing remained a common user complaint.

Based on user feedback, the Nepomuk indexing and search has been replaced with the Baloo framework[22] based on Xapian.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "What do you do for desktop search in VDI and RDSH?". Blogpost by Brian Madden on brainmadden.com. Retrieved on March 25, 2015.

- ^ Anthony Ha (2 June 2008). "Lookeen offers a new way for Outlook users to search". VentureBeat. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ Robert L. Mitchell (8 May 2013). "X1 rises again with Desktop Search 8, Virtual Edition". Computerworld. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Security special report: Who sees your data?", Computer Weekly, 2006-04-25.

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Technology - Search wars hit desktop computers". bbc.co.uk. 26 October 2004. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "KMWorld - The Evolution of Desktop Search". February 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2019..

- ^ "dtSearch UK Blog - Desktop Wars". Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ "SearchMax". goebelgroup.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Everything Search Engine". voidtools. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ "Vegnos". Vegnos. Retrieved 27 December 2013.

- ^ Niall Kennedy (17 October 2006). "The current state of video search". Niall Kennedy. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Niall Kennedy (15 October 2006). "The current state of audio search". Niall Kennedy. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Indexing Service". microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Indexing with Microsoft Index Server". microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Windows Search: Technical FAQ". microsoft.com. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "AppleSearch". infomotions.com. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ eduardo casais. "Converter of current to real US dollars - using the GDP deflator". areppim.com. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Apple - Press Info - Apple to Ship Mac OS X "Tiger" on April 29". apple.com. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "A first look at Tracker 0.6.0". Ars Technica. 26 July 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Recoll user manual". lesbonscomptes.com. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Linux.com". Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Baloo - KDE Community Wiki".

- ^ "Home". opensuse.org.

Desktop search

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Core Functionality

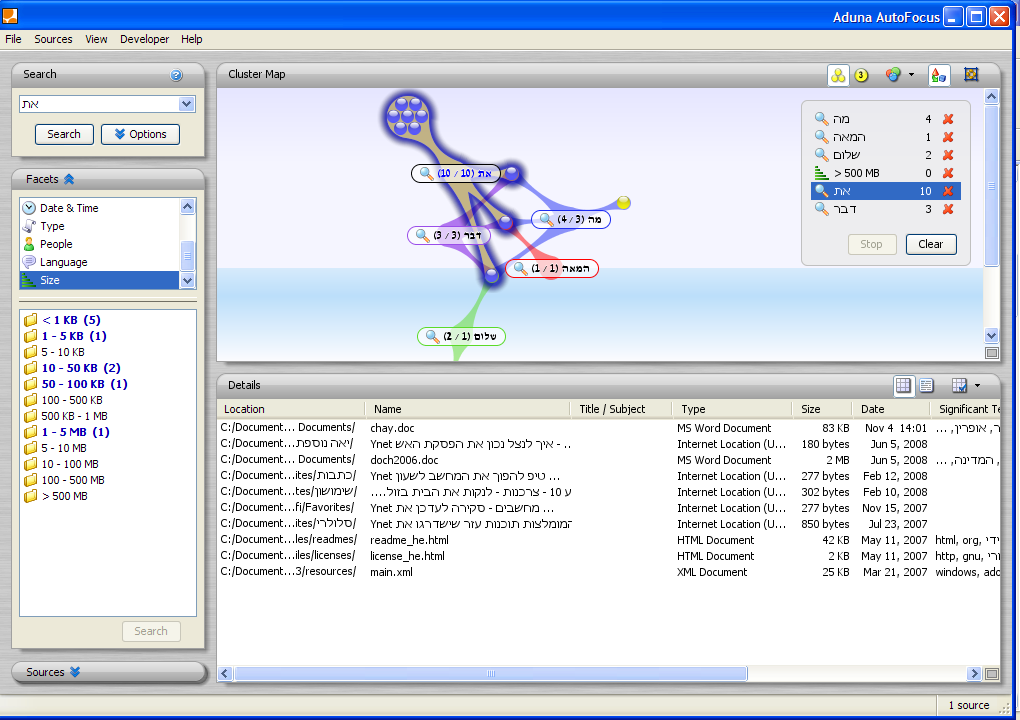

Desktop search encompasses software applications or built-in operating system components designed to locate and retrieve data stored on a user's personal computer, including files, emails, browser histories, and multimedia content across local hard drives and connected storage.[1][2] These tools differ from web-based search engines by targeting the local filesystem and application data stores, enabling searches of content within documents, metadata properties, and even encrypted or archived files when supported.[3] At its core, desktop search operates through an indexing mechanism that preprocesses and catalogs file contents and attributes for efficient access. Indexing scanners traverse directories to extract full-text from supported formats—such as plain text, PDFs, Word documents, emails in PST or MBOX formats, images via OCR where applicable, and audio/video transcripts if integrated—while recording metadata like file paths, modification dates, authors, and tags into a centralized database or inverted index structure.[11][12] This process runs in the background, updating incrementally upon file changes to minimize resource overhead, though initial builds can consume significant CPU and disk I/O; for instance, Windows Search indexes properties and content from over 200 file types, prioritizing user-specified locations like Documents or Outlook data.[4] Query processing constitutes the retrieval phase, where user-entered terms—ranging from keywords and phrases to advanced filters like date ranges or file types—are parsed, expanded via stemming or synonyms if configured, and matched against the index using algorithms such as term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) for relevance ranking.[4] Results are typically displayed with previews, thumbnails, or snippets, supporting Boolean logic (AND/OR/NOT), proximity searches, and natural language queries in modern implementations, thereby providing near-instantaneous responses compared to unindexed filesystem scans that could take minutes for large drives.[12] Privacy controls often allow exclusion of sensitive directories, and some tools integrate federated search to extend beyond the desktop to networked or cloud-synced repositories without compromising local primacy.[2]Historical Context and Evolution Summary

Desktop search originated from rudimentary file-finding utilities in operating systems during the 1990s, evolving from basic filename matching to content indexing influenced by emerging web search technologies. Early tools like AppleSearch, introduced in 1994 for Macintosh systems, enabled full-text searches across documents by maintaining local indexes of file contents, marking one of the first comprehensive local search implementations.[13] Similarly, Microsoft's Indexing Service debuted in Windows NT 4.0 in 1996 primarily for web content via IIS, but expanded in Windows 2000 to index local folders using filters for content extraction and USN Journal for efficient change tracking.[8] Apple's Sherlock, released with Mac OS 8.5 in 1998, built on AppleSearch's architecture to provide hybrid local and web searches, adopting indexed services for faster retrieval.[14] The mid-2000s saw a surge in dedicated desktop search tools, driven by web giants adapting their indexing prowess to local environments amid growing personal data volumes. Google Desktop Search was previewed in October 2004 and formally launched as version 1.0 on March 7, 2005, offering free full-text indexing of files, emails, and browser history with sub-minute query responses on typical hardware.[9] Microsoft followed with Windows Desktop Search (initially as MSN Desktop Search in 2004), which integrated into Windows XP and later evolved into the native Windows Search in Vista (released January 2007), shifting to a background SearchIndexer.exe process that prioritized user libraries and supported extensible protocols for non-file content.[8] Apple introduced Spotlight in Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger on April 29, 2005, as a system-wide feature using metadata and content indexes for instant, selection-based searches across the filesystem.[14] Subsequent evolution emphasized OS integration over standalone apps, addressing performance issues like resource-intensive indexing while incorporating advanced features such as metadata handling and federated searches. In Windows 7 (2009), users gained granular control over indexing scopes via Control Panel, with defaults enabling content searches; Windows 10 (2015) added metadata-only modes for lighter footprints and folder exclusions.[8] macOS refined Spotlight with privacy-focused local processing and AI-like natural language queries in later versions, though core indexing principles remained rooted in 2005 designs.[14] This progression reflected a causal shift from manual, slow filename scans—common in Windows 95 eras, often taking minutes—to proactive, inverted-index databases mirroring web engines, enabling near-real-time full-text access despite local hardware constraints.[15] By the 2010s, standalone tools declined as OS-native solutions dominated, though third-party options persisted for specialized needs like forensic or enterprise local searches.[16]History

Pre-2000s Precursors

Early efforts in desktop search emerged from command-line utilities in Unix-like systems, which provided foundational mechanisms for locating files through pre-built indexes rather than real-time scans. Thefind command, originating in early Unix versions around 1973, enabled recursive searches based on criteria like name, size, or modification time but operated slowly by traversing the filesystem on each invocation. Complementing this, the locate utility, introduced in BSD Unix distributions by the mid-1980s (with widespread adoption in 4.3BSD releases circa 1986), maintained a periodically updated database of filenames and paths generated by updatedb, allowing near-instantaneous queries for filename matches across large filesystems.[17] These tools prioritized filename and metadata over content indexing, reflecting hardware constraints of the era where full-text searches risked excessive processing time.

In the personal computing domain, graphical precursors appeared in the late 1980s, exemplified by Lotus Magellan, released in 1989 for MS-DOS and early Windows environments. Developed by Lotus Development Corporation, Magellan indexed local disk contents—including files, emails, and applications—for full-text search, enabling users to query document interiors rather than just names or extensions.[18] This represented an advance over basic file managers, as it built inverted indexes akin to library catalogs, though limited by the era's storage and CPU capabilities, often requiring manual re-indexing after file changes. Such third-party software addressed the growing data volumes on PCs, where hierarchical folders proved inadequate for content retrieval.

Operating systems began incorporating rudimentary search by the mid-1990s, though still filename-centric and non-indexed. Microsoft Windows 95, launched in 1995, offered a built-in search dialog that scanned drives in real-time for matching filenames, a process that could take minutes on larger disks without content analysis.[8] Similarly, Apple introduced Sherlock in Mac OS 8 (1997), which extended file searches to include some web integration but relied on live scans for local files, lacking persistent indexing until later iterations.[5] These OS-level features underscored the shift toward user-friendly interfaces but highlighted performance bottlenecks, paving the way for indexed solutions in the 2000s.

2000s Boom and Key Innovations

The early 2000s marked a surge in desktop search development, driven by exploding local storage capacities—average hard drive sizes grew from around 20-40 GB in 2000 to over 100 GB by 2005—and the success of web-scale search engines like Google, which inspired analogous tools for personal data.[8] This period saw major tech firms release flagship products, shifting search from rudimentary file-name matching to full-text indexing across documents, emails, images, and browser history, enabling sub-second queries on terabyte-scale datasets.[19] Google pioneered the boom with Desktop Search, beta-launched on October 14, 2004, as a free downloadable tool that indexed users' emails, files, and web history while preserving privacy through local processing.[19] Its full 1.0 release on March 7, 2005, added features like cached web snippets and plugin extensibility for custom data sources, amassing millions of downloads within months and pressuring competitors to accelerate their efforts.[9] Microsoft followed with Windows Desktop Search on May 16, 2005, an add-on for Windows XP, 2000, and Server 2003 that integrated with Outlook and supported over 200 file formats via extensible indexing protocols.[20] Apple introduced Spotlight in Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger on April 29, 2005, embedding metadata-driven search directly into the OS kernel for real-time querying of files, calendars, and apps without user-installed software.[14] Key innovations included inverted indexing adapted from web search for local use, allowing relevance-ranked results based on term frequency and proximity, as in Google's implementation which mirrored its PageRank-inspired scoring for desktop content.[19] Privacy-focused local caching prevented data transmission to servers, addressing early concerns over surveillance, while hybrid metadata-and-content search—exemplified by Spotlight's use of file tags, creation dates, and OCR on images—enabled semantic filtering beyond keywords.[14] Microsoft's tool advanced federated search, querying remote shares alongside local indexes, and introduced protocol handlers for uniform access to proprietary formats like PST files, laying groundwork for OS-native integration in Windows Vista (2006). These advancements reduced search times from minutes to milliseconds on consumer hardware, with benchmarks showing Google's tool handling 10,000+ documents in under 100 ms post-indexing.[8]2010s Integration and Decline of Standalone Tools

During the 2010s, operating system developers prioritized embedding advanced search capabilities directly into their platforms, which eroded the market for independent desktop search applications. Microsoft's Windows Search, building on its foundations from Windows Vista, received iterative enhancements throughout the decade, including improved indexing efficiency and integration with cloud services in Windows 10 released in 2015. These updates enabled faster file retrieval across local drives and emphasized natural language queries, making third-party alternatives less essential for average users.[8] Apple similarly advanced Spotlight in macOS, with macOS Yosemite in 2014 introducing support for web searches, unit conversions, dictionary lookups, and direct app actions from the search interface, expanding its utility beyond basic file indexing. Subsequent versions, such as macOS Sierra in 2016, added Siri integration for voice-based desktop queries, further embedding search into the system's core ecosystem. This native evolution aligned with Apple's focus on seamless hardware-software synergy, reducing incentives for standalone tools on macOS platforms.[21] The decline of standalone desktop search tools accelerated with high-profile discontinuations, exemplified by Google's termination of Google Desktop in September 2011 after seven years of availability across Windows, macOS, and Linux. Google attributed the move to native operating system improvements providing "instant access to data, whether online or offline," rendering the product redundant. This exit, following earlier feature removals like cross-computer search in January 2010, signaled a broader market contraction, as enhanced OS tools addressed core user needs for local content discovery without additional software overhead.[22][23] Consequently, the standalone sector shifted toward niche applications for enterprise or specialized indexing, with vendors like Copernic persisting but facing diminished consumer adoption amid rising OS sufficiency and the parallel growth of cloud-based file synchronization services. Security concerns, including vulnerabilities in older tools like Google Desktop, further deterred maintenance and development, as integrated OS search benefited from vendor-backed updates and reduced exposure to third-party risks.[24][25]Core Technologies

Indexing Mechanisms

Indexing mechanisms in desktop search systems primarily revolve around constructing and updating an inverted index, a data structure that maps extracted terms from files to their locations within documents, enabling efficient full-text retrieval without scanning entire file systems during queries.[11] This approach contrasts with brute-force searches by precomputing term-document associations, typically storing postings lists that include document identifiers, term frequencies, and optionally positions for supporting phrase or proximity matching.[26] The indexing process initiates with a full system crawl, where file paths are queued for analysis, often starting with user-specified locations to limit scope and resource demands.[11] Protocol handlers identify file types and invoke format-specific filters—such as IFilter interfaces in Windows—to extract raw text and metadata like file names, modification dates, authors, and sizes from diverse formats including PDFs, Word documents, and emails.[12] Extracted text is then tokenized into terms via word-breaking algorithms that handle punctuation, whitespace, and language-specific rules, followed by normalization steps like case-folding to lowercase and optional stemming to conflate morphological variants (e.g., "running" to "run").[26] Stopwords may be filtered or retained depending on query needs, as their omission reduces index size but can impair exact phrase searches.[26] Terms are subsequently inserted into the inverted index dictionary, with postings lists appended or updated to reflect occurrences; construction often involves sorting terms alphabetically for the dictionary and document IDs sequentially for lists to facilitate merging and compression.[26] Metadata is stored in parallel value-based indices for exact matching and sorting, complementing the inverted structure for hybrid queries combining keywords with filters (e.g., by date or type).[11] To manage storage, postings are compressed using techniques like delta encoding (d-gaps between sorted document IDs) and variable-length codes such as Golomb-Rice, achieving reductions to 7-40% of original text volume while preserving query speed.[26] Maintenance relies on incremental updates to avoid full re-scans, triggered by file system notifications—such as NTFS change journals in Windows—that signal modifications, additions, or deletions.[27] Upon notification, affected files are re-queued for differential processing: unchanged content is skipped, while modified sections are re-parsed and merged into the index, with deletions removing corresponding postings.[12] This background operation balances responsiveness with system load, though performance scales inversely with indexed volume, where large indices (e.g., millions of files) can exceed several gigabytes and demand periodic optimization to merge segments and reclaim space.[11] In practice, initial indexing of typical desktops completes in hours, with ongoing updates consuming minimal CPU as files change.[12]Search Algorithms and Query Processing

Desktop search systems utilize inverted indexes as the foundational data structure for search algorithms, mapping terms extracted from file contents and metadata to lists of containing documents (or file paths) to enable sublinear-time query resolution on local corpora.[28] This structure supports efficient retrieval by avoiding full scans of the file system, with postings lists compressed to minimize storage overhead while preserving positional information for phrase queries.[26] In implementations like Windows Search, the inverted index handles both content words and property values, allowing operators such as CONTAINS for exact term matching or FREETEXT for fuzzy relevance.[4] Query processing in desktop search follows standard information retrieval pipelines, initiating with parsing to decompose user input into tokens via lexical analysis, which includes splitting on whitespace and punctuation, case normalization to lowercase, and optional stemming or lemmatization to conflate morphological variants (e.g., "running" to "run").[29] Stopwords—high-frequency terms like "the" or "and" that carry low discriminative value—are typically filtered out to reduce index noise and improve precision, though some systems retain them for phrase queries.[30] Advanced processing may incorporate query expansion, such as synonym mapping or semantic broadening using thesauri, but this is less common in resource-constrained local environments compared to web-scale engines due to computational limits.[31] Retrieval algorithms then intersect or union the postings lists for query terms, prioritizing exact matches for conjunctive queries (e.g., AND semantics) or ranked expansion for disjunctive ones (e.g., OR), often employing optimizations like skip lists for faster list traversal.[32] Ranking follows retrieval, applying scoring functions to order candidates by estimated relevance; BM25, a probabilistic model, predominates in full-text contexts, computing scores as a sum over query terms of term frequency (saturated to avoid bias toward long documents), weighted by inverse document frequency (to downplay common terms), and normalized by document length.[33] While proprietary details vary—e.g., Apple Spotlight emphasizes metadata recency and user history without disclosed formulas—desktop tools generally adapt such bag-of-words models, augmented by local factors like file modification date or type for hybrid relevance.[34] These algorithms prioritize speed over exhaustive precision, given the small-to-medium scale of personal indexes (often millions of terms across thousands of files).[35]Data Types and Metadata Handling

Desktop search systems typically support a wide array of data types, including text-based documents such as .txt, .pdf, .docx, .doc, .rtf, and .pptx files, as well as emails, spreadsheets, and presentations.[36] Media files like images (e.g., JPEG, PNG), audio, and videos are also indexed, often extending to over 170 formats in commercial tools such as Copernic Desktop Search.[37] Binary formats including HTML, CSV, XML, and archives receive partial content extraction where feasible, prioritizing searchable elements over full binary parsing.[38] For text-heavy data types like documents and emails, indexing involves extracting and storing full content alongside structural elements, enabling keyword matching within bodies and attachments.[39] Images and videos, lacking inherent text, rely on embedded thumbnails, captions, or optical character recognition (OCR) for limited content search, with primary emphasis on file names, paths, and sizes.[40] Emails are handled by parsing headers, subjects, and bodies from formats like .pst or .mbox, integrating sender, recipient, and timestamp data for contextual retrieval.[25] Metadata handling enhances search precision across data types by extracting attributes such as creation/modification dates, authors, titles, file sizes, and custom tags, which are stored in inverted indexes for rapid querying.[41] In systems like Apple Spotlight, over 125 metadata attributes—including EXIF data for images (e.g., camera model, GPS coordinates) and ID3 tags for audio—are indexed separately from content, allowing filters likekind:pdf or date:today.[42] Windows Search extracts similar properties via property handlers, supporting advanced filters on metadata fields during indexing to avoid real-time computation overhead.[12] Tools may employ libraries like Apache Tika for standardized metadata extraction from diverse formats, ensuring consistency in attributes like MIME types and encodings.[43] This approach privileges empirical relevance over exhaustive content scanning, as metadata often yields faster, more accurate results for non-textual data.[44]

Operating System Implementations

Microsoft Windows

Windows Search serves as the primary desktop search platform in Microsoft Windows, enabling rapid querying of local files, emails, applications, settings, and other indexed content through integration with the Start menu, taskbar, and File Explorer.[4] Introduced initially as Windows Desktop Search (WDS) in August 2004 as a free downloadable add-on for Windows XP and Windows Server 2003, it replaced the older Indexing Service by supporting content-based searches beyond file names and metadata, including natural language processing for properties like authors and dates.[8] With the release of Windows Vista on January 30, 2007, Windows Search became natively integrated, leveraging the SearchIndexer.exe process to maintain a centralized index of user-specified locations.[8] The indexing mechanism operates in three main stages: queuing uniform resource locators (URLs) for files and data stores via file system notifications or scheduled scans; crawling to access content; and updating the index through filtering, word breaking, stemming, and storage in a proprietary database optimized for full-text and property-based retrieval.[11] Supported formats encompass over 200 file types, such as Office documents (.docx), images (.jpeg), PDFs, and emails via protocols like MAPI for Outlook integration, with extracted properties including titles, keywords, and timestamps to enable relevance-ranked results.[11] Users can customize indexing via the Indexing Options control panel applet, adding or excluding folders, pausing operations, or rebuilding the index to address performance issues, though high CPU or disk usage during initial crawls remains a common complaint on systems with large datasets.[45] In Windows 10, released on July 29, 2015, search functionality was bundled with Cortana for voice-activated queries but decoupled in subsequent updates to focus on local desktop capabilities, incorporating federated search for apps and web results while prioritizing indexed local data.[8] Windows 11, launched on October 5, 2021, enhanced desktop search with expanded indexing options under Settings > Privacy & security > Searching Windows, allowing toggles for cloud file inclusion (e.g., OneDrive) and "Enhanced" mode for deeper system-wide coverage, alongside faster query processing via optimized algorithms that reduce latency for common searches.[46] As of the Windows 11 version 25H2 update in late 2025, further refinements include proactive integration with clipboard content for instant "Copy & Search" functionality and improved relevance for file content matches, though these build on the core local indexing unchanged since Vista-era foundations.[47] Despite these advances, Windows Search has faced criticism for incomplete indexing of encrypted or network drives without explicit configuration, and occasional inaccuracies in ranking due to reliance on heuristic scoring rather than exhaustive real-time scans.[45]Apple macOS and iOS Integration

Spotlight serves as the primary desktop search mechanism in macOS, introduced on April 12, 2005, with Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger as a replacement for the Sherlock utility, leveraging metadata indexing to enable queries across files, applications, emails, contacts, calendars, and system preferences.[14] The system operates via a background daemon that builds and maintains an inverted index of content attributes, supporting natural language queries, previews, and quick actions without requiring full file scans during searches.[5] In iOS and iPadOS, Spotlight provides analogous search capabilities, accessible by swiping downward on the home screen, indexing installed apps, messages, photos, web history, and location data for device-local results, with iCloud-synced content extending visibility to cloud-stored items like notes and documents. Cross-platform integration relies on iCloud for data synchronization, permitting macOS Spotlight to retrieve and display iOS-originated content—such as Mail messages, Photos libraries, and iCloud Drive files—provided the same Apple ID is used and syncing is enabled, thus unifying search results across ecosystems without direct device-to-device querying. Continuity features augment this by facilitating Handoff, where an active Spotlight-initiated task or web search on one device can transfer to another nearby device via Bluetooth and Wi-Fi, maintaining session continuity for signed-in users.[48][49] Advancements in macOS Tahoe (version 15, released September 2025) enhance Spotlight with persistent search history, clipboard integration for retrieving recent copies, and executable actions like app launches or calculations directly from results, features that interoperate with iOS through Universal Clipboard and shared iCloud data stores.[50][51] Indexing remains on-device for privacy, with optional exclusions via System Settings to prevent scanning of sensitive directories, though iCloud reliance introduces potential exposure risks if cloud security is compromised.[52]Linux and Unix-like Systems

In Linux and Unix-like systems, desktop search lacks a unified, kernel-level implementation akin to Windows Search or macOS Spotlight, instead relying on desktop environment frameworks, standalone applications, and legacy command-line utilities. This modular approach allows customization but results in variability across distributions and user setups, with indexing often opt-in to manage resource usage.[10] The GNOME desktop environment integrates Tracker as its primary indexing and search provider, a middleware component that builds a semantic database of files, metadata, emails, and application data using RDF and full-text extraction via libtracker-sparql. Introduced in the mid-2000s and refined through versions like Tracker 3 (stable since 2019), it powers searches in the Activities overview, Nautilus file manager, and apps via SPARQL queries, supporting content indexing for formats like PDF and Office documents after initial scans. Users configure indexing scopes through GNOME Settings to balance performance, as Tracker miners run as daemons monitoring filesystem changes.[53][54] KDE Plasma utilizes Baloo, a lightweight file indexing framework developed for Frameworks 5 (released 2014), emphasizing low RAM usage through on-disk storage and incremental updates via inotify. Baloo indexes filenames, extracted content, and metadata for queries in KRunner, Dolphin, and Plasma Search, with tools likebalooctl for enabling, monitoring, and limiting to specific folders or excluding content indexing to reduce overhead. Configurations in ~/.config/baloofilerc allow fine-tuning, addressing common complaints of high initial CPU during full scans.[55][56]

Standalone open-source tools bridge gaps across environments; Recoll, based on the Xapian engine since its initial release around 2007, provides GUI-driven full-text search over documents, emails, and archives in formats like HTML, PDF, and ZIP, with desktop integration via GNOME Shell providers or KDE runners. It supports stemming, phrase queries, and filtering without real-time monitoring, indexing on demand for privacy-focused users. Other utilities like FSearch offer instant filename matching inspired by Windows' Everything, using pre-built databases for sub-second results on large filesystems.[7][57][58]

In traditional Unix-like systems, desktop search equivalents are sparse, prioritizing command-line tools like locate (enhanced as mlocate since the 1990s), which queries a daily-updated slocate database for filenames but omits content analysis or GUI interfaces. Modern ports extend these to GUI wrappers, yet full-text desktop indexing remains Linux-centric, with FreeBSD or Solaris users adapting Linux tools via ports or relying on find and grep for ad-hoc searches. This ecosystem reflects Unix philosophy's emphasis on composable tools over integrated services.[59][60]

Third-Party and Alternative Tools

Commercial Solutions

Commercial desktop search solutions offer enhanced indexing, faster query processing, and broader integration with email clients and cloud services compared to native operating system tools, targeting professional users and enterprises seeking improved productivity. These tools often employ proprietary algorithms to handle large datasets, including emails, attachments, and documents, while providing advanced filtering and preview capabilities.[61] Pricing models typically include subscriptions or one-time licenses, with features scaled for individual or organizational use.[62] Copernic Desktop Search indexes files, emails, and documents across local drives, supporting over 175 file types with offline access and keyword mapping for refined results.[63] It emphasizes lightning-fast search speeds and advanced filtering, available via a 30-day free trial before requiring purchase.[64] The software maintains an updated index of user data for quick retrieval, distinguishing it from non-indexing alternatives.[65] X1 Search provides federated searching across local files, emails, attachments, and Microsoft 365 sources such as Teams, OneDrive, and SharePoint, with real-time capabilities extended to Slack in version 10 released in 2025.[66] Designed for both personal and business workflows, it supports targeted queries without full data migration, priced at approximately $79 per year for mid-sized business editions.[62] Users benefit from in-place searching that preserves data security and enables immediate action on results.[67] Lookeen specializes in Windows and Outlook integration, searching emails, attachments, tasks, notes, and contacts with AI-assisted features in its 2025 edition.[68] Pricing starts at €69 per year per user for the Basic edition, including the Windows app and discovery panel, escalating to €99 for Business with enhanced enterprise tools.[69] It supports virtual desktop infrastructure (VDI) and shared indexes for teams, offering a 14-day free trial.[70] UltraSearch from JAM Software delivers non-indexing searches by directly querying the NTFS Master File Table, enabling instant results on Windows systems without preprocessing overhead.[71] Commercial editions cater to enterprise-wide deployment with central indexing options and extensive filtering, suitable for large-scale file locates.[72] This approach contrasts with indexing-based tools by minimizing resource use during idle periods.[73]Open-Source Options

Open-source desktop search tools provide customizable, privacy-focused alternatives to proprietary systems, enabling users to index and query local files without external dependencies or licensing costs. These solutions often leverage libraries like Xapian or Lucene for efficient full-text retrieval, supporting diverse file formats such as PDFs, emails, and office documents. While varying in platform support and integration depth, they emphasize local processing to minimize data exposure risks associated with cloud-based indexing. DocFetcher stands out as a cross-platform application written in Java, compatible with Windows, macOS, and Linux, where it indexes file contents for rapid keyword-based searches.[74] Released initially in 2007 with updates continuing through version 1.1.25, it processes over 100 file types via Apache Tika parsers and offers features like date-range filtering and Boolean operators.[75] Independent evaluations in 2025 highlight its superiority over native Windows Search in speed and accuracy for content-heavy drives, attributing this to its lightweight indexing that avoids real-time overhead.[76] However, the core open-source variant receives limited active maintenance, prompting some users to explore forks or complementary scripts for extended functionality.[77] Recoll, powered by the Xapian information retrieval library, delivers full-text search across Unix-like systems, Windows, and macOS, excelling in handling large personal archives with stemming, synonym support, and wildcard queries.[7] Its indexer scans documents incrementally, updating only modified files to conserve resources, and integrates with desktop environments via a Qt-based GUI for configuration and result previewing.[7] As of 2022 benchmarks, Recoll outperforms filename-only tools in precision for mixed-format collections, though it requires manual setup for optimal performance on non-standard paths.[78] Users in Linux communities frequently pair it with tools like fsearch for hybrid filename-content workflows, citing its low CPU footprint during queries.[79] In Linux distributions, environment-specific indexers like GNOME's Tracker provide integrated search via SPARQL queries on metadata and text, enabling semantic filtering within the desktop shell. Tracker 3.x, stable as of 2023 builds, supports real-time updates and content extraction for formats including images and spreadsheets, but incurs higher idle resource demands—up to 5-10% CPU on modern hardware—leading to configurable throttling options.[54] KDE Plasma's Baloo offers analogous capabilities with SQL-backed storage, though both face critiques for occasional index corruption in dynamic file systems without user intervention.[80] Specialized tools like Open Semantic Desktop Search extend beyond basic retrieval by incorporating text analytics for entity extraction and faceted navigation, targeting research-oriented users on Debian-based systems.[81] These options collectively address gaps in commercial tools, such as vendor telemetry, but demand technical familiarity for tuning index scopes and query parsers to achieve sub-second response times on terabyte-scale datasets.[82]Privacy, Security, and Ethical Considerations

Historical Vulnerabilities and Incidents

In August 2017, Microsoft addressed a remote code execution vulnerability in Windows Search (CVE-2017-8620), where improper handling of objects in memory could enable an attacker to gain control of the system if a user opened a maliciously crafted file or visited a compromised website.[83] From 2022 onward, attackers exploited a zero-day flaw in Windows Search via thesearch-ms protocol, allowing remotely hosted malware to masquerade as local file searches and execute payloads, such as through Word documents that triggered indexing of malicious content.[84] In July 2023, security firms reported campaigns abusing this protocol to deliver remote access trojans (RATs) by embedding JavaScript in webpages that invoked Windows Search to fetch and run arbitrary executables from attacker-controlled servers.[85] Similar tactics persisted into 2024, with malware like MetaStealer using spoofed search interfaces to evade endpoint detection during clickfix attacks.[86][87]

On macOS, a 2025 vulnerability dubbed "Sploitlight" (CVE-2025-31199) in Spotlight's indexing process enabled attackers to bypass Transparency, Consent, and Control (TCC) privacy protections, exposing metadata and contents from restricted directories like Downloads and Apple Intelligence caches, potentially leaking geolocation or biometric data.[88] Apple patched this flaw in a March 2025 security update following disclosure by Microsoft Threat Intelligence.[89]

Earlier third-party desktop search tools, such as Google Desktop Search released in 2004, faced scrutiny for vulnerabilities enabling remote data access via insecure indexing of browser caches and networked shares, with a specific flaw patched by Google in February 2007 after researcher disclosure, though no confirmed exploits occurred.[90] These incidents highlighted risks in local indexing exposing sensitive files over networks without adequate isolation.[24]

Risks of Local Indexing and Data Exposure

Local indexing in desktop search systems creates structured databases of file contents, metadata, and paths to enable rapid querying, but this process inherently risks exposing sensitive data stored on the device. If the index database is compromised—through malware, privilege escalation, or flawed access controls—attackers can enumerate and extract confidential information such as documents containing personal identifiers, financial records, or intellectual property without directly scanning the filesystem, which is computationally intensive. This exposure is amplified because indexes often store plaintext excerpts or keywords from diverse file types, including those with embedded sensitive elements like passwords in configuration files or health data in documents.[91][92] In Microsoft Windows, the Search Indexer has faced multiple vulnerabilities enabling remote code execution (RCE) or elevation of privilege, allowing attackers to manipulate or read index data. For instance, CVE-2020-0614 permitted local attackers to gain elevated privileges by exploiting how the Indexer handles memory objects, potentially exposing indexed sensitive content across the system. More recently, a critical Windows Defender flaw confirmed in December 2024 involved improper index authorization, which could let malware authorize unauthorized access to search indexes containing user data. Additionally, a 2022 zero-day in Windows Search allowed remotely hosted malware to trigger searches that executed malicious files, indirectly leveraging the index for persistence or data theft. These issues stem from the Indexer's reliance on iFilters—plugins for parsing 290+ file types—which, if buggy, process untrusted inputs during indexing, creating entry points for exploitation.[93][94][84] On Apple macOS, Spotlight's indexing introduces privacy risks via vulnerabilities that bypass Transparency, Consent, and Control (TCC) protections, granting unauthorized access to files users intended to shield. The "Sploitlight" vulnerability, disclosed by Microsoft Threat Intelligence in July 2025, exploited Spotlight's plugin handling to read metadata and contents from protected directories, including geolocation trails in photos, timestamps, and face recognition data, without prompting for TCC approval. Even without exploits, Spotlight's optional "Improve Search" feature has transmitted anonymized query data to Apple servers since at least macOS versions prior to Sequoia, potentially correlating local indexed content with user behavior. Disabling indexing mitigates local exposure but does not eliminate risks from partial metadata retention or system-wide search integrations.[88][95] Across platforms, local indexing exacerbates risks in shared or networked environments, where improperly permissioned indexes on accessible drives can reveal hidden sensitive files via search queries. Historical tools like Google Desktop Search (discontinued in 2011) demonstrated this by allowing remote vulnerabilities to access indexed data, underscoring that even local indexes become vectors if integrated with network features or third-party extensions. Attackers compromising a device can thus query indexes faster than raw filesystem traversal, accelerating data exfiltration in breaches.[24][96]User Controls and Best Practices

Users can mitigate privacy risks in desktop search by configuring indexing to exclude sensitive directories, such as those containing financial records or personal documents, thereby preventing inadvertent exposure through search queries or potential breaches of the index database.[12] [97] On Microsoft Windows, access advanced indexing options via Settings > Privacy & Security > Searching Windows, where users select specific locations to index or exclude, and disable cloud content search to limit data sharing with remote services.[98] [99] For Apple macOS, Spotlight's Privacy settings allow exclusion of folders or volumes by adding them to a block list in System Settings > Spotlight > Search Privacy, which halts indexing of those areas and reduces the scope of searchable content.[52] [100] Disabling Siri Suggestions and Location Services for search further prevents metadata leakage, as these features can transmit query patterns to Apple servers under certain conditions.[101] In Linux and Unix-like systems, users of tools like Recoll or Tracker should manually configure index paths to avoid scanning privileged or sensitive directories, enforcing file permissions (e.g., chmod 600) on index files to restrict access, and encrypting filesystems with LUKS to protect against unauthorized reads of indexed data.[102] Best practices include:- Periodic index rebuilding or pausing: Temporarily halt indexing during high-security needs or rebuild to remove obsolete data, accessible in Windows via the Indexing Options dialog and in macOS by deleting the Spotlight index via Terminal command

sudo mdutil -E /.[98] - Limiting index scope: Index only essential file types and locations to minimize data aggregation, reducing the attack surface if the index is compromised.[12]

- Multi-user isolation: In shared environments, configure per-user indexing or exclude other profiles' directories to prevent cross-access, as default Windows settings may surface files from all accounts.[103]

- Software updates and monitoring: Maintain up-to-date search components to patch known vulnerabilities, and monitor logs for anomalous indexing activity.[102]

- Alternatives for high-privacy needs: Opt for non-indexing manual searches or encrypted vaults for sensitive data, avoiding full-desktop tools altogether.[97]