Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

GIO (software)

View on Wikipedia| GIO | |

|---|---|

| Developer | The GNOME Project |

| Written in | C |

| Type | System library |

| License | GNU Lesser General Public License |

| Website | docs |

GIO (Gnome Input/Output) is a library, designed to present programmers with a modern and usable interface to a virtual file system. It allows applications to access local and remote files with a single consistent API, which was designed "to overcome the shortcomings of GnomeVFS" and be "so good that developers prefer it over raw POSIX calls."[1]

GIO serves as low-level system library for the GNOME Shell/GNOME/GTK software stack and is being developed by The GNOME Project. It is maintained as a separate library, libgio-2.0, but it is bundled with GLib. GIO is free and open-source software released under the GNU Lesser General Public License.

Features

[edit]- The abstract file system model of GIO consists of a number of interfaces and base classes for I/O and files.

- There are a number of stream classes, similar to the input and output stream hierarchies that can be found in frameworks like Java.

- There are interfaces related to applications and the types of files they handle.

- There is a framework for storing and retrieving application settings.

- file type detection with xdgmime (xdg = X Desktop Group = freedesktop.org)[2]

- file monitoring with inotify[3]

- file monitoring with FAM[4]

- There is support for network programming, including name resolution, lowlevel socket APIs and highlevel client and server helper classes.

- There is support for connecting to D-Bus, sending and receiving messages, owning and watching bus names, and making objects available on the bus.

Beyond these, GIO provides facilities for file monitoring, asynchronous I/O and filename completion. In addition to the interfaces, GIO provides implementations for the local case. Implementations for various network file systems are provided by the GVfs package as loadable modules.

See also

[edit]- KIO – an analogous KDE library

- gVFS – a user-space virtual filesystem relying on GIO

- GnomeVFS – the older Gnome library for the same purposes

References

[edit]- ^ "GIO Reference Manual". Retrieved July 31, 2025.

- ^ "xdgmime in GIO git". Retrieved July 31, 2025.

- ^ "inotify in GIO git". Retrieved July 31, 2025.

- ^ "FAM in GIO git".[permanent dead link]

External links

[edit]GIO (software)

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Purpose

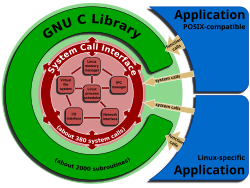

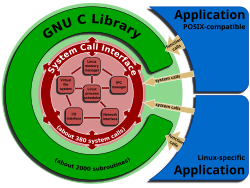

GIO is a core module of the GLib utility library, providing a high-level abstraction for input/output operations in C-based applications, particularly those in the GNOME ecosystem. It enables portable handling of diverse resources through URI-based interfaces, allowing developers to perform file system operations on local files, network protocols like HTTP and FTP, and device backends without writing platform-specific code. This abstraction layer simplifies access to a virtual file system (VFS), treating various storage and network locations uniformly as files or streams.[2][1] The primary purpose of GIO is to offer a modern, extensible framework for I/O that supports both synchronous and asynchronous operations, facilitating efficient integration with event loops in desktop applications. Key concepts include stream-based I/O for reading and writing data (via interfaces like GInputStream and GOutputStream), event-driven file monitoring to detect changes in resources, and metadata management for attributes such as file permissions and timestamps. By encapsulating low-level details, GIO promotes code reusability and portability across Unix-like systems, Windows, and other environments supported by GLib.[1] GIO was introduced as part of GLib to modernize I/O mechanisms for contemporary desktop needs, replacing older GNOME-specific libraries like GnomeVFS with a more integrated and developer-friendly approach embedded directly in GLib. This shift emphasizes a unified resource model, where URIs serve as the common denominator for accessing everything from local directories to remote servers, reducing complexity in application development. GLib itself provides the foundational utilities upon which GIO builds, while implementations like GVfs handle the backend VFS details.[4][5]Development Context

GIO was developed as an integral component of the GNOME project, specifically within the GLib library, to overcome the limitations of prior input/output frameworks like GnomeVFS, which struggled with accessibility for non-specialized applications and scalability in modern desktop environments. GIO was first released as part of GLib 2.16 on March 10, 2008.[6][7][8] This initiative aimed to create a more robust foundation for cross-platform desktop applications by providing a unified interface for file operations and network protocols.[2] The primary motivations for GIO's creation centered on establishing a virtual file system (VFS) that enhances GNOME's desktop capabilities, enabling seamless handling of diverse protocols such as SMB for network shares, WebDAV for collaborative document access, and integration with GStreamer for media stream I/O.[9][10] By addressing GnomeVFS's shortcomings, such as its isolation from standard file access methods, GIO facilitates broader ecosystem interoperability while supporting asynchronous operations essential for responsive user interfaces.[4] Development was led by the GLib team under the GNOME project, drawing on standards from freedesktop.org to ensure alignment with shared desktop infrastructure like D-Bus for inter-process communication and FUSE for userspace file systems.[11][12] GIO is released under the GNU Lesser General Public License version 2.1 or later (LGPL-2.1-or-later), which promotes its adoption in both open-source and proprietary software by allowing dynamic linking without requiring derivative works to be open-sourced.[2] This licensing, combined with GLib's design, ensures portability across Linux, Windows, and other Unix-like systems, enabling GNOME applications to function consistently on diverse platforms.[13][14]History

Origins and Initial Release

GIO was conceived in 2007 as part of enhancements to the GLib utility library, aimed at unifying and modernizing input/output operations within the GNOME desktop environment by replacing the fragmented and aging I/O APIs, such as GnomeVFS, that had accumulated over previous versions.[15] This initiative sought to provide a more robust, extensible framework for handling files, networks, and other resources, addressing limitations in the existing ecosystem that hindered seamless integration across GNOME applications. Development efforts began in late 2007, aligning with preparations for future GNOME releases to streamline virtual file system interactions.[16] The library made its initial public release as part of GLib 2.16.0 on March 10, 2008, introducing core APIs such as GFile for abstract file representation, GInputStream for reading data, and GOutputStream for writing data.[6] These foundational components were designed to offer a consistent interface for both local and remote resources, marking a significant shift toward a virtual file system abstraction in GLib. The release emphasized compatibility with prior GLib versions while laying the groundwork for broader adoption in GNOME.[6] Early development faced challenges in ensuring thread-safety for concurrent I/O operations, given GLib's evolving multi-threading support, and in providing robust Unicode handling for internationalized file names across diverse backends.[2] These issues were critical to making GIO suitable for modern, multi-threaded applications and global user bases, with solutions integrated into the initial APIs to support asynchronous operations and URI-based encoding.[2] Following its debut, GIO saw rapid initial adoption within GNOME core applications, notably integrated into the Nautilus file manager for handling file operations, automounting, and virtual file system features in the GNOME 2.22 release.[17] This quick uptake demonstrated GIO's viability as a replacement for legacy systems, enabling improved performance and extensibility in key desktop components.[17]Evolution and Key Milestones

GIO's development has progressed through iterative enhancements in GLib releases, transforming it from a foundational I/O library into a comprehensive virtual file system (VFS) capable of handling diverse environments, including remote, cloud, and containerized setups. This evolution emphasizes improved portability, asynchronous operations, and integration with modern desktop technologies, while maintaining backward compatibility.[1] GVfs, providing initial userspace backends for remote file systems in GIO, was first released with GNOME 2.22 in March 2008. This update built on GIO's core abstractions to enable seamless interaction with protocols like HTTP on platforms such as Windows, laying the groundwork for broader VFS functionality.[18][19] Subsequent improvements in GLib 2.22 (September 2009) focused on asynchronous APIs, providing cancellable DNS resolution via GResolver and enhanced support for IP addresses and UNIX domain sockets. Additionally, GFileMonitor was added, enabling efficient file and directory change notifications, which improved responsiveness in applications monitoring dynamic content. These changes strengthened GIO's suitability for event-driven desktop applications.[20][21] GLib 2.36 (March 2013) advanced cross-platform capabilities with improvements to D-Bus integration, including fixes for generated code in gdbus-codegen to support desktop notifications without warnings. This release improved reliability in heterogeneous environments, facilitating GIO's use in multi-platform GNOME applications.[22] In GLib 2.50 (September 2016), enhancements included better error handling and logging annotations, promoting stability for virtualized file operations.[23] GLib 2.68 (March 2021) included improvements to error handling in GIO output streams.[24] Ongoing development in GLib releases, such as 2.76.6 in September 2023 with improved TLS support and async operations in GIO, and 2.87.0 in November 2025 with Unicode 17.0 support and extensions to gdbus-codegen, continues to enhance GIO's portability and integration with modern standards.[25][26]Architecture

Core Components

GIO's core components form the foundational abstractions for handling files, data streams, and related metadata in a portable and extensible manner. At the heart of these is the GFile interface, which serves as an abstract representation of files and directories across various file systems. GFile objects are lightweight and immutable, designed to identify resources without performing I/O upon creation; instead, they facilitate operations such as querying parents, children, and basenames through methods likeg_file_get_parent() and g_file_get_basename(). This interface supports multiple URI schemes, including file:// for local files and http:// for remote resources, enabling uniform handling of diverse locations via constructors like g_file_new_for_uri() and scheme detection with g_file_get_uri_scheme().[27]

Complementing GFile are the stream classes GInputStream and GOutputStream, which provide base abstractions for reading from and writing to data sources in a buffered and seekable fashion. GInputStream, as an abstract base class, implements core input operations including read() to fetch bytes into a buffer, skip() to advance over data, and close() to release resources, allowing for efficient handling of sequential input without direct dependency on underlying file descriptors. Similarly, GOutputStream handles output with analogous methods like write() for emitting data and close() for finalization, supporting buffered writes and splicing between streams to copy content reliably. These streams form the basis for all I/O in GIO, enabling subclasses to adapt to specific backends while maintaining a consistent API.[28]

For resource representation and file attributes, GIO employs GIcon and GFileInfo. GIcon is a minimal interface for portable icon handling, allowing serialization, hashing, and equality checks without embedding pixel data; it supports themed, emblemed, and loadable icon variants to represent resources abstractly. GFileInfo, in turn, acts as a container for file metadata, encapsulating details such as size (via g_file_info_get_size() from the standard::size attribute), MIME type (g_file_info_get_content_type()), and permissions through attribute queries and setters. These components enable efficient metadata retrieval and manipulation, with GFileInfo optimized for direct accessors to avoid repeated attribute parsing.[29][30]

Error handling in GIO relies on the GError structure from GLib, tailored for I/O operations within the G_IO_ERROR domain. GError captures error domains, codes, and messages, with GIO-specific enums like G_IO_ERROR_PERMISSION_DENIED (code 14) signaling access restrictions and G_IO_ERROR_NOT_FOUND (code 1) indicating missing resources. This mechanism ensures precise reporting, convertible from system errors via functions like g_io_error_from_errno(), promoting robust application behavior across platforms.[31][32]

GIO's threading model integrates seamlessly with GLib's main event loop to support non-blocking operations, using thread-default contexts to schedule I/O callbacks and maintain responsiveness without explicit thread management. This foundation extends to higher-level features like GVfs for virtual file system emulation.[1]

Virtual File System (GVfs)

GVfs serves as the primary userspace virtual filesystem (VFS) implementation for GIO, enabling transparent access to diverse storage resources including local devices, remote servers, and cloud services. It operates through a collection of daemons and libraries that extend GIO's core abstractions, with a master daemon coordinating backend processes via D-Bus for inter-process communication. This daemon-based architecture allows GVfs to mount resources on demand without requiring kernel-level privileges, fostering a unified view of filesystems across protocols. To support non-GIO applications, GVfs integrates with FUSE (Filesystem in Userspace), where the gvfsd-fuse daemon automatically establishes a mount point at /run/user/$UID/gvfs (or ~/.gvfs as fallback) upon session startup, exposing GVfs-managed resources to POSIX-compliant tools.[33][34][35] The extensibility of GVfs relies on pluggable backends, each tailored to specific protocols and responsible for handling authentication, connection management, and data transfer. Core backends include support for FTP (via the ftp backend for unencrypted transfers), SFTP (using the sftp backend for secure SSH-based access), SMB/CIFS (leveraging libsmbclient in the smb backend for Windows and Samba shares), and Google Drive (integrated through the google-drive backend using the unmaintained libgdata library (as of 2022) and GNOME Online Accounts for OAuth authentication).[36][37] Additional backends cover protocols like WebDAV, NFS, HTTP, and device-specific interfaces such as MTP for media players or OBEX for Bluetooth transfers. These plugins operate as separate daemons (e.g., gvfsd-sftp), activated lazily when a resource is accessed, ensuring efficient resource utilization while maintaining protocol-specific features like encryption and credential storage.[38][39] Mounting and unmounting in GVfs are facilitated through GIO APIs that abstract the process, allowing applications to interact with resources via GFile objects without direct protocol awareness. For explicit mounting, functions like g_file_mount_mountable() initiate the operation asynchronously, triggering the relevant backend daemon to establish the connection and create a GMount representation. Unmounting employs g_mount_unmount_with_operation(), which safely detaches the resource after confirming no open handles remain, preventing data loss. GVfs also implements automatic shadow mounts for removable media, such as USB drives or optical discs, detected via integration with Udev and volume monitors; these mounts appear transparently in the user's namespace without manual intervention, supporting hotplug scenarios in desktop environments.[40][34][41] Security in GVfs emphasizes isolation and controlled access, particularly in sandboxed environments like Flatpak and Snap. It integrates with xdg-desktop-portal, a D-Bus-based framework that mediates resource requests from contained applications, allowing GVfs mounts (e.g., remote shares) to be accessed via portals without granting blanket permissions to the gvfs-daemon. This portal-mediated approach enforces user consent for operations like mounting network locations, mitigating risks such as unauthorized data exposure in untrusted apps; for instance, Flatpak apps can request GVfs FUSE mounts through the org.freedesktop.portal.FileChooser interface, ensuring sandbox boundaries are respected. Authentication for backends, such as keyring storage for SFTP credentials, further bolsters security by avoiding plaintext persistence.[42][43][44] Performance optimizations in GVfs focus on efficient remote access and daemon oversight to minimize latency and overhead. Backend daemons employ connection caching, where clients maintain thread-local pools of reusable connections to reduce setup costs for repeated operations on protocols like SFTP or SMB. For FUSE-managed mounts, the kernel's page cache handles local buffering of remote data, while GVfs implements metadata caching to accelerate directory listings and attribute queries without full network round-trips. The fuse daemon itself is managed dynamically, starting only as needed and terminating idle backends to conserve resources, though this userspace layer can introduce overhead compared to kernel filesystems.[34][45]Key Features

Unified Resource Handling

GIO provides a unified interface for accessing diverse resources through theGFile abstraction, which treats files, directories, and other data sources as lightweight, immutable objects regardless of their underlying location or protocol. This design allows applications to perform operations like reading, writing, and querying without needing to handle protocol-specific details, promoting portability across local filesystems, network resources, and virtual mounts. By leveraging URI schemes, GIO abstracts away the complexities of different storage backends, enabling consistent behavior in desktop environments.[27]

URI parsing and resolution in GIO are facilitated by functions such as g_file_new_for_uri(), which constructs a GFile instance from a given URI string, automatically detecting the scheme (e.g., "file://", "http://") and normalizing the path for cross-platform compatibility. This process ensures that URIs are resolved correctly, handling edge cases like relative paths or escaped characters, without performing any I/O at creation time. Scheme detection allows GIO to route operations to appropriate backends, such as local filesystems or remote protocols.[27]

Cross-protocol operations are supported through GFile, enabling seamless reading and writing to local files, HTTP resources, or archives like tar and zip files. For instance, applications can open an HTTP URI for downloading content or mount an archive as a virtual directory for extraction, with operations abstracted to standard methods like g_file_read() or g_file_create(). This unification relies on GVfs backends for non-local protocols and archive handling, which provide read-only access to compressed formats in a transparent manner.[27][46]

File monitoring is achieved via GFileMonitor, which watches for changes such as file creations, deletions, modifications, or attribute updates in a directory or specific file. Developers create a monitor using g_file_monitor() or g_file_monitor_directory() on a GFile object and connect to the changed signal to receive notifications about events, including renames or attribute alterations. This mechanism operates in the thread-default main context, allowing efficient reactivity without polling.[21]

MIME and content type detection in GIO integrates with the shared-mime-info database to automatically identify file types based on extensions, magic bytes, or sniffed content. The g_content_type_guess() function analyzes a filename and/or data buffer to return the appropriate MIME type (e.g., "text/plain" or "image/jpeg"), setting an uncertainty flag if the match is ambiguous. This enables applications to handle content appropriately, such as selecting the right viewer or processor, drawing from the standardized freedesktop.org MIME specification.[47]

In GNOME environments, GIO supports desktop-specific URIs like "trash://" for managing deleted files and "recent://" for accessing recently used documents, facilitated by GVfs extensions. Operations such as trashing a file via g_file_trash() map these URIs to underlying storage, providing a consistent user experience across applications. This handling ensures that virtual resources behave like standard files, with global session tracking for mounts.[27]

Asynchronous I/O Support

GIO supports asynchronous I/O operations through a callback-based model, enabling non-blocking access to files, streams, and other resources without halting the application's main thread. Methods such asg_file_read_async() initiate these operations by scheduling I/O requests with an optional GAsyncReadyCallback for completion notification and a GCancellable for interruption support. Upon invocation, the function returns immediately, queuing the task in the underlying system, while the paired _finish method, like g_file_read_finish(), retrieves results and propagates errors when called from the callback. This approach ensures responsive applications, particularly in graphical interfaces where blocking I/O could cause freezes.[48][1]

For more structured asynchronous programming, GIO employs GTask as an equivalent to promises or futures, facilitating cancellable operations with robust error handling. Created via g_task_new(), a GTask instance manages data across threads using g_task_run_in_thread() to execute synchronous code asynchronously, returning results through methods like g_task_propagate_pointer(). Cancellation is handled by integrating GCancellable, allowing immediate error returns via g_task_return_error_if_cancelled(), which propagates G_IO_ERROR_CANCELLED without halting ongoing background work. This mechanism simplifies complex async workflows by encapsulating state, priorities, and exceptions.[49]

Asynchronous operations in GIO integrate seamlessly with GLib's GMainContext for event loop management and UI thread safety. Callbacks dispatch in the thread-default main context where the operation originates, retrieved via g_main_context_get_thread_default(), ensuring that I/O completions do not block or cross threads unexpectedly. Developers can push custom contexts using g_main_context_push_thread_default() to isolate async tasks, preventing interference with the primary UI loop and maintaining responsiveness in multi-threaded environments.[50][1]

Common use cases for GIO's async I/O include background file transfers, such as downloading large resources without interrupting user interactions, and real-time monitoring of file changes or network events, where continuous polling would otherwise degrade performance. These scenarios leverage non-blocking reads and writes to keep applications fluid, especially in desktop environments.[1]

Performance optimizations in GIO's async framework include an internal worker thread pool that enables parallel execution of multiple operations, reducing latency for concurrent I/O tasks. Buffering strategies are implemented at the stream level, with methods like g_input_stream_read_async() handling data in chunks up to G_MAXSSIZE to minimize overhead, while io_priority parameters allow priority queuing—lower numerical values (e.g., G_PRIORITY_HIGH) ensure critical tasks execute before others in the queue. These features collectively enhance throughput without requiring manual thread management.[51][1]

API and Usage

Primary Interfaces

GIO's primary interfaces are exposed through its public C API, which is built on the GObject type system for object-oriented programming in C. Developers include the header file<gio/gio.h> to access these interfaces, typically using pkg-config --cflags --libs gio-2.0 for compilation flags and linking.[2] All GIO objects inherit from GObject, requiring proper memory management via reference counting; objects are referenced with g_object_ref() and unreferenced with g_object_unref() to avoid leaks.

The core class hierarchy centers on GFile, an immutable interface representing files or directories in a virtual filesystem without performing I/O on creation. GFile supports URI-based locations (e.g., file://, http://) and provides methods for common operations like querying metadata, copying, and replacing contents. For instance, g_file_query_info() retrieves file attributes such as size, modification time, and MIME type using specified attributes in a query string, with options controlled by GFileQueryInfoFlags like G_FILE_QUERY_INFO_NOFOLLOW_SYMLINKS to avoid traversing symbolic links.[27][52] The g_file_copy() function handles file duplication to a destination, supporting progress monitoring via a callback and flags for behavior like overwriting or preserving attributes.[53] Similarly, g_file_replace() enables atomic file replacement, optionally backing up the original and setting permissions via GFileCreateFlags such as G_FILE_CREATE_REPLACE_DESTINATION for overwriting without confirmation.[54]

Stream classes form the foundation for data I/O: GInputStream is an abstract base for reading data, offering methods like g_input_stream_read() to fetch bytes into a buffer and g_input_stream_close() to release resources.[28] Complementing it, GOutputStream handles writing, with g_output_stream_write() for outputting data, g_output_stream_flush() to ensure buffered content is sent, and g_output_stream_close() for cleanup.[55] These streams integrate with GFile through methods like g_file_read() (returning a GInputStream) and g_file_create() (yielding a GOutputStream), enabling abstracted access to local files, networks, or virtual resources.[27]

For directory traversal, GFileEnumerator iterates over file listings obtained via g_file_enumerate_children(), yielding GFileInfo objects for each entry with details like names and types. Key methods include g_file_enumerator_next_file() for synchronous retrieval and g_file_enumerator_close() to free the enumerator, which must always be called after use.[56]

Enums and flags enhance control: GFileQueryInfoFlags specify query behaviors, while GFileCreateFlags manage creation options like private mount points or backups. Legacy interfaces like GIOChannel from GLib are deprecated in favor of GIO's stream-based API since GLib 2.2, as channels lack modern streaming abstractions for asynchronous and cancellable operations.[57]

Integration Examples

GIO provides a flexible API for integrating file and resource operations into applications, supporting both local and remote resources through its unified interface. For basic file read and write operations, developers typically begin by constructing aGFile object from a local file URI using g_file_new_for_path(). Asynchronous reading is initiated with g_file_read_async(), specifying a callback for completion, followed by g_file_read_finish() to retrieve the input stream and check for errors such as G_IO_ERROR_EXISTS or permission issues via the GError parameter. Writing follows a similar pattern: g_file_replace_async() opens the file in read-write mode, potentially creating a backup, and g_file_replace_finish() handles the output stream while managing errors like insufficient space.[27]

Remote access via GVfs enables seamless interaction with network protocols like SFTP. To mount an SFTP share, create a GFile from a URI such as sftp://user@host/path using g_file_new_for_uri(), then invoke g_file_mount_mountable_async() with a GMountOperation for authentication prompts and a GCancellable for potential interruptions. Upon completion, confirmed by g_file_mount_mountable_finish(), directory enumeration proceeds with g_file_enumerate_children_async() on the mounted file, listing contents asynchronously to support responsive UIs. This leverages GVfs's backend for secure, transparent remote file handling.[58]

File monitoring integrates event-driven responses to changes in watched resources. A GFileMonitor is created for a directory using g_file_monitor_directory(), with flags like G_FILE_MONITOR_WATCH_MOVES to detect renames, creations, and deletions. Developers connect a callback to the "changed" signal, which receives parameters including the affected files and event type (e.g., G_FILE_MONITOR_EVENT_CREATED), allowing applications to update displays or trigger actions in real-time. Monitoring is terminated with g_file_monitor_cancel() when no longer needed, ensuring efficient resource use.[21]

Error handling and cancellation enhance robustness in long-running operations. The GCancellable object is passed to asynchronous methods like g_file_copy_async() for large downloads, enabling user-initiated interruption via g_cancellable_cancel(). In the finish callback, applications check if the operation was cancelled by examining the GError code, such as G_IO_ERROR_CANCELLED, and respond by cleaning up resources or notifying the user, preventing hangs in interactive scenarios.[27]

Language bindings via GObject Introspection facilitate GIO usage beyond C. In Python, the gi.repository.Gio module allows direct access to APIs, such as loading file contents asynchronously with Gio.File.load_contents_async(), integrating seamlessly with Python's event loops for non-blocking I/O. Similarly, in JavaScript via GJS, Gio.File methods like load_contents_async() are promisified for modern async/await patterns, enabling web-like scripting for GNOME extensions and applications.[59][60]

Adoption and Extensions

Use in GNOME Ecosystem

GIO serves as a foundational component in the GNOME ecosystem, enabling consistent I/O operations across applications and desktop services through its unified abstractions for files, networks, and D-Bus communications.[2] In core GNOME applications, Nautilus, the default file manager, extensively uses GIO for URI navigation and file operations. It leverages the GFile interface to handle diverse resources uniformly, including local files, remote servers via protocols like SMB or FTP, and virtual filesystems provided by GVfs, allowing users to browse and manage content without protocol-specific code. This integration replaced the older GnomeVFS, simplifying maintenance and enhancing features like real-time file monitoring with GFileMonitor.[61][15] Evince, the document viewer, employs GIO for embedded file handling, particularly through metadata attributes to store and retrieve user-specific data such as bookmarks, page positions, and zoom levels. For instance, attributes likemetadata::evince::page enable persistent state across sessions, queried and set via GFile's info methods, ensuring seamless document resumption without embedding data directly in files.[62]

GNOME Shell integrates GIO for desktop shell functionalities, including thumbnail generation and search indexing. Thumbnails are managed using GIO's thumbnail namespace attributes, where applications query the cache via GFileInfo to display previews in the overview and file dialogs, with GnomeDesktopThumbnailFactory handling creation based on GIO lookups. Search indexing relies on Tracker, which uses GIO for file access, monitoring directories with GFileMonitor, and determining MIME types via GIO's content type functions to populate its semantic index for quick overview searches.[63][64][65]

In media and system tools, GIO streams power GStreamer pipelines through dedicated elements like giosrc and giosink, facilitating input from and output to GIO-supported URIs, such as HTTP streams or local files, in applications like Videos or Rhythmbox. For power management, GNOME components access UPower via D-Bus using GIO's GDBus interfaces, enabling queries for battery status and events in tools like the power profile switcher without low-level socket handling.[66][67]

Enhancements in GIO have bolstered Wayland compatibility within GNOME by improving D-Bus proxy handling and portal integrations for sandboxed file access, reducing reliance on X11-specific I/O paths in session management.

GIO's file attribute queries contribute to GNOME's accessibility features, allowing applications to retrieve and set descriptive metadata—such as custom icons or labels—that assistive technologies like Orca can leverage for better file navigation and screen reader announcements in file managers and explorers.[68]