Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

G-sharp minor

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

| Relative key | B major |

|---|---|

| Parallel key | G-sharp major →enharmonic: A-flat major |

| Dominant key | D-sharp minor |

| Subdominant key | C-sharp minor |

| Enharmonic key | A-flat minor |

| Component pitches | |

| G♯, A♯, B, C♯, D♯, E, F♯ | |

G-sharp minor is a minor scale based on G♯, consisting of the pitches G♯, A♯, B, C♯, D♯, E, and F♯. Its key signature has five sharps.[1]

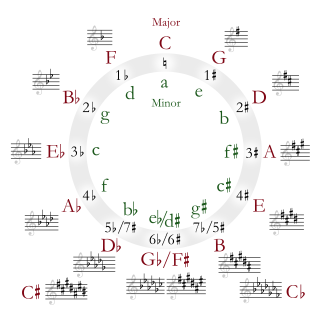

Its relative major is B major. Its parallel major, G-sharp major, is usually replaced by its enharmonic equivalent of A-flat major, since G-sharp major has an F![]() in its key signature, making it less convenient to use. A-flat minor, its enharmonic, has seven flats, whereas G-sharp minor only has five sharps; thus G-sharp minor is sometimes used as the parallel minor for A-flat major. (The same enharmonic situation occurs with the keys of D-flat major and C-sharp minor, and in some cases, with the keys of G-flat major and F-sharp minor).

in its key signature, making it less convenient to use. A-flat minor, its enharmonic, has seven flats, whereas G-sharp minor only has five sharps; thus G-sharp minor is sometimes used as the parallel minor for A-flat major. (The same enharmonic situation occurs with the keys of D-flat major and C-sharp minor, and in some cases, with the keys of G-flat major and F-sharp minor).

The G-sharp natural minor scale is:

Changes needed for the melodic and harmonic versions of the scale are written in with accidentals as necessary. The G-sharp harmonic minor and melodic minor scales are:

Scale degree chords

[edit]The scale degree chords of G-sharp minor are:

- Tonic – G-sharp minor

- Supertonic – A-sharp diminished

- Mediant – B major

- Subdominant – C-sharp minor

- Dominant – D-sharp minor

- Submediant – E major

- Subtonic – F-sharp major

Music in G-sharp minor

[edit]Despite the key rarely being used in orchestral music other than to modulate, it is more common in keyboard music, as in Piano Sonata No. 2 by Alexander Scriabin, who actually seemed to prefer writing in it. Dmitri Shostakovich used the key in the second movement of his 8th String Quartet, and the slow fourth movement of his 8th Symphony is also in this key. If G-sharp minor is used in orchestral music, composers generally write B♭ wind instruments in the enharmonic B-flat minor, rather than A-sharp minor to facilitate reading the music (or A instruments are used instead, giving a transposed key of B minor).

Few symphonies are written in G-sharp minor; among them are Nikolai Myaskovsky's 17th Symphony, Elliot Goldenthal's Symphony in G-sharp minor (2014) and an abandoned work of juvenilia by Marc Blitzstein.

The minuet from the Piano Sonata in E-flat major, Op. 44 ("The Farewell") by Jan Ladislav Dussek is in G-sharp minor.

Frédéric Chopin composed a Polonaise in G-sharp minor, Op. posth., in 1822. His Étude Op. 25 No. 6, the first mazurka from his Op. 33 and his 12th prelude from the 24 Preludes, Op. 28, are in G-sharp minor as well.

Modest Mussorgsky wrote the movements, "Il vecchio castello" (The Old Castle) and "Bydło" (Cattle), from Pictures at an Exhibition in G-sharp minor.

Liszt's "La campanella" from his Grandes études de Paganini is in G-sharp minor.

Alexander Scriabin's Second Piano Sonata "Sonata-Fantasy", Op. 19, is in G-sharp minor.

Maurice Ravel's "Scarbo" from Gaspard de la nuit (1908), is in G-sharp minor.

Sibelius wrote the slow movement of his Third Symphony in G-sharp minor.

Beethoven wrote the sixth movement of his 14th String Quartet in G-sharp minor.

Bach also wrote the movements, "Prelude and Fugue No. 18", from both books of The Well-Tempered Clavier which is also in G-sharp minor; both movements from Book 1 end with a Picardy third, utilizing a B-sharp in the final G-sharp major chord.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Tapper, Thomas. First Year Musical Theory (rudiments of Music). United States, A. P. Schmidt, 1912.

G-sharp minor

View on GrokipediaScale and key signature

Natural minor scale

The natural G-sharp minor scale consists of the pitches G♯, A♯, B, C♯, D♯, E, F♯, and G♯, used both in ascending and descending forms.[2][3] It follows the standard natural minor interval pattern of whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole steps between consecutive notes.[4] On the piano keyboard, these pitches correspond to five black keys (G♯, A♯, C♯, D♯, F♯) and two white keys (B, E).[5] The natural minor scale forms the basis of the G-sharp minor key, defining its core pitches without chromatic alterations.[3] Its relative major is B major, which uses the same pitches and key signature.[3]Key signature

The key signature of G-sharp minor features five sharps: F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, and A♯. These accidentals follow the standard order derived from the circle of fifths, progressing by perfect fifths: F♯ (first), C♯ (second), G♯ (third), D♯ (fourth), and A♯ (fifth).[6][7] In the treble clef, the sharps are positioned at the locations corresponding to their natural pitches: F♯ on the top line, C♯ in the space above the middle line, G♯ on the second line from the bottom, D♯ on the fourth line from the bottom, and A♯ in the second space from the bottom. In the bass clef, they appear as F♯ on the fourth line from the bottom, C♯ in the second space from the bottom, G♯ on the bottom line, D♯ on the third line from the bottom, and A♯ in the first space from the bottom. This placement adheres to conventional notation practices, ensuring the accidentals align vertically and diagonally for clarity.[8][9] G-sharp minor shares this identical key signature with its relative major, B major, which also employs the same five sharps to define its tonal center a minor third higher.[10][11] The presence of five sharps introduces greater notational complexity compared to keys with fewer accidentals, complicating sight-reading and transposition as performers must mentally apply multiple alterations to the natural notes on the staff.[12][13]Key relationships

Relative and parallel keys

The relative major of G-sharp minor is B major. These two keys share the same key signature of five sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, and A♯) and the same set of pitches, with B major starting on the third degree of the G-sharp minor scale.[14][15] The relative major is structurally built on the mediant—the third scale degree—of the minor scale, which in G-sharp minor is B.[16] The parallel major of G-sharp minor is G-sharp major, which shares the same tonic note (G♯) but is in the major mode. To form G-sharp major from the G-sharp minor scale, the third (B to B♯), sixth (E to E♯), and seventh (F♯ to F𝄪) degrees are raised by a half step.[17][18] G-sharp major has a theoretical key signature of eight sharps, often notated with seven accidentals consisting of one double sharp and six sharps (F𝄪, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯), though it is rarely used in practice due to its complexity and is typically enharmonically equivalent to A-flat major.[7]Enharmonic equivalent

The enharmonic equivalent of G-sharp minor is A-flat minor, which employs a key signature of seven flats (B♭, E♭, A♭, D♭, G♭, C♭, F♭) in contrast to the five sharps (F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯) of G-sharp minor.[1] Both keys generate the same sequence of pitches—G♯/A♭, A♯/B♭, B/C♭, C♯/D♭, D♯/E♭, E/F♭, F♯/G♭—differing only in their notational representation.[19] In practice, composers select G-sharp minor over A-flat minor when working within sharp-key frameworks, such as sequences related to its relative major B major, to maintain consistency with fewer accidentals overall.[2] A-flat minor, however, is often preferred in flat-key contexts or for instruments requiring transposition, like those in B♭, where the additional flats align more readily with the prevailing notation and reduce the need for frequent accidentals in performance.[20] Composers frequently switch between these enharmonic notations mid-piece for notational convenience, such as respelling chords to avoid double sharps (e.g., F𝄪 in G-sharp minor contexts) or to simplify readability during modulations, a technique exemplified in Chopin's flexible approach to enharmonic respelling.[20]Characteristics

Affective qualities

In the tradition of 18th- and 19th-century key affect theory, sharp minor keys were associated with unease and lamentation, as described by theorists like Christian Schubart in his Ideen zu einer Ästhetik der Tonkunst (1806).[21] Similarly, Hugo Riemann later attributed to G-sharp minor an "impulsive power" within a "sphere of super-sensual presentation of ideal feelings," blending sober views of everyday life with noble inspiration.[22] Modern perceptions of G-sharp minor often emphasize tension and introspection, stemming from its relative rarity compared to flat-key equivalents like A-flat minor.[23] The key's five-sharp signature, particularly with double-sharps in the harmonic and melodic minor scales, contributes to an awkwardness in notation that can heighten a dramatic or exotic quality in performance.[24] In equal temperament, these multiple sharps may subtly enhance dissonant tensions, amplifying the key's intensely emotional and mysterious aura akin to G minor's associations with discontent and gnashing intensity.[22]Notation and usage

In the harmonic minor scale of G-sharp minor, the seventh scale degree is raised by a semitone from F-sharp to F-double-sharp, providing a leading tone that resolves strongly to the tonic G-sharp and facilitating dominant-to-tonic cadences.[25] This alteration introduces double-sharps into the notation, particularly evident in the raised seventh's role within diatonic harmonies.[26] The melodic minor scale in G-sharp minor modifies the natural minor form for ascending lines by raising both the sixth degree to E-sharp and the seventh to F-double-sharp, enhancing smoothness and avoiding the augmented second interval between the sixth and seventh degrees present in the harmonic minor.[27] On descent, it reverts to the natural minor scale (G-sharp, A-sharp, B, C-sharp, D-sharp, E, F-sharp), aligning with the stepwise motion typical of descending melodies.[27] The abundance of accidentals in G-sharp minor—five sharps in the key signature plus frequent double-sharps in the harmonic and melodic variants—creates significant notation challenges, increasing the risk of reading errors and complicating score preparation.[26] In orchestral and band contexts, composers often prefer the enharmonic A-flat minor to sidestep these double-sharps, even though it requires a seven-flat key signature, as the simpler accidental notation aids performers across instrument sections.[28] While G-sharp minor sees limited overall use due to its relative inaccessibility compared to keys with fewer accidentals, it appears more frequently in string music, where transposition to this key can leverage open-string positions for resonance and efficient fingering on instruments like the violin.[29]Harmony

Diatonic chords

The diatonic chords of G-sharp minor are derived from the natural minor scale, which consists of the pitches G♯, A♯, B, C♯, D♯, E, and F♯. These chords are constructed by stacking alternate notes (thirds) from the scale, forming triads on each degree.[30] The basic diatonic triads, using Roman numeral analysis, are as follows:| Degree | Roman Numeral | Chord Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | i | G♯ minor | G♯–B–D♯ |

| II | ii° | A♯ diminished | A♯–C♯–E |

| III | III | B major | B–D♯–F♯ |

| IV | iv | C♯ minor | C♯–E–G♯ |

| V | v | D♯ minor | D♯–F♯–A♯ |

| VI | VI | E major | E–G♯–B |

| VII | VII | F♯ major | F♯–A♯–C♯ |

| Degree | Roman Numeral | Chord Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | i7 | G♯ minor seventh | G♯–B–D♯–F♯ |

| II | iiø7 | A♯ half-diminished seventh | A♯–C♯–E–G♯ |

| III | III7 | B major seventh | B–D♯–F♯–A♯ |

| IV | iv7 | C♯ minor seventh | C♯–E–G♯–B |

| V | v7 | D♯ minor seventh | D♯–F♯–A♯–C♯ |

| VI | VI7 | E major seventh | E–G♯–B–D♯ |

| VII | VII7 | F♯ dominant seventh | F♯–A♯–C♯–E |