Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

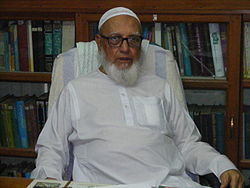

Ghulam Azam

View on Wikipedia

Ghulam Azam[a] (7 November 1922 – 23 October 2014) was a Bangladeshi politician and writer who served as ameer of Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, the largest Islamist political party in Bangladesh.[1]

Key Information

As a leader of the Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan, ahead of the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war he supported the Pakistan Army in its Operation Searchlight (1971), a crackdown on Bengali nationalists in the then East Pakistan (later Bangladesh), by leading the formation of the East Pakistan Central Peace Committee. Azam has been accused of forming paramilitary groups for the Pakistani Army, including Razakars, and Al-Badr during the ensuing 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. These militias opposed the Mukti Bahini members who fought for the independence of Bangladesh, and were also involved in war crimes during the Bangladesh genocide.[2][3]

After the independence of Bangladesh, he led the Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh until 2000.[4][5][6][7][8] His citizenship was cancelled by the Bangladeshi government in 1978 and he subsequently lived informally in the country till 1994 when it was reinstated by the Supreme Court.[9][10][11][12]

Azam was arrested on 11 January 2012 by the International Crimes Tribunal of Bangladesh (ICT) on charges of committing war crimes during the liberation war.[13][14][15] On 15 July 2013, the ICT found him guilty of war crimes such as conspiring, planning, incitement to and complicity in committing the genocide and was sentenced to 90 years in jail.[16][17] The tribunal stated that Azam deserved capital punishment for his activity during the war, but was given a lenient punishment of imprisonment because of his age and poor health condition.[18][19][20] The trial was criticized by international observers such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Human Rights Watch, which was initially supportive of a trial subsequently criticized "strong judicial bias towards the prosecution and grave violations of due process rights", calling the trial process deeply flawed and unable to meet international fair trial standards.[21][22][23][24]

He died at age 91, following a stroke, on 23 October 2014 at BMU.[25] Thousands of people attended his funeral prayers that were televised and held at Baitul Mukarram.[26]

Family background and education

[edit]Sheikh Ghulam Azam was born on 7 November 1922 in his maternal home, Shah Saheb Bari of Lakshmibazar, Dacca, Bengal Presidency. He was the eldest son of Sheikh Ghulam Kabir and Sayeda Ashrafunnisa. His ancestral home is Maulvi Bari in Birgaon Village, Brahmanbaria, his paternal family is the Sheikh family of Birgaon, he descends from Sheikh Zaqi in his 6th generation who had migrated from the Middle East, as a Muslim preacher and settled in the settlement of Birgaon beside the Meghna River in the 18th Century.[27] His family's residence in the area is referred to as Maulvi Bari due to the fact that the family had produced several scholarly figures during their stay in Bengal. Ghulam Azam's father Ghulam Kabir was a Mawlana and so was his father Sheikh Abdus Subhan.[28] The tradition of religious scholarship in the family was started by his great-grandfather Sheikh Shahabuddin Munshi who was considered an Alim and a Munshi based in the area east of the Meghna river.[29] His mother Sayeda Ashrafunnisa was the daughter of Shah Sayed Abdul Munim whose family is a Sayed Peer family, his father Shah Sayed Emdad Ali was a descendant of Shah Sayed Sufi Hosseini who arrived from Iran via Delhi in 1722 AD and settled in what is now known as Sayedabad of Kaliakor.[28][27] Ghulam Azam's education began at the local madrasa in Birgaon and then completed his secondary school education in Dhaka. After that, he enrolled at Dacca University where he completed BA and MA degrees in political science.[30]

Early political career

[edit]University

[edit]While studying at University of Dhaka, Azam became active in student politics and was elected as the General Secretary of the Dhaka University Central Students' Union (DUCSU) for two consecutive years between 1947 and 1949.[30][b]

Jamaat-e-Islami

[edit]In 1950, Azam left Dhaka to teach political science at Government Carmichael College in Rangpur. During this time, he was influenced by the writings of Abul Ala Maududi, and he joined Maududi's party, Jamaat-e-Islami, in 1954, and was later elected as the Secretary General of Jamaat-e-Islami's East Pakistan branch.[30]

In 1964, the government of Ayub Khan banned Jamaat-e-Islami and its leaders, including Azam, and imprisoned them for eight months without trials. He played a prominent role as the general secretary of the Pakistan Democratic Movement formed in 1967, and later he was elected as the member of the Democratic Action Committee in 1969 to transform the anti-Ayub movement into a popular uprising. In 1969, he became the ameer of Jamaat in East Pakistan. He and other opposition leaders took part in the Round Table Conference held in Rawalpindi in 1969 to solve the prevailing political impasse in Pakistan.[30] On 13 March 1969, Khan announced his acceptance of their two fundamental demands of parliamentary government and direct elections.[32]

In the run-up to the 1970 Pakistani general election, Azam, together with leaders of a number of other parties in East Pakistan (including the Pakistan Democratic Party, National Awami Party, Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, and the Pakistan National League), protested against the Awami League for reportedly breaking up public meetings, physical attacks on political opponents, and the looting and destruction of party offices.[33] During 1970, while Azam was the head of Jamaat-e-Islami East Pakistan, a number of political rallies, including rallies of Jamaat-e-Islami, were attacked by armed mobs alleged to be incited by Awami League.[34][35]

Bangladesh Liberation War

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

Activities during 1971 War

[edit]During the Bangladesh Liberation War, Azam took a political stance in support of unified Pakistan,[36][37] and repeatedly denounced Awami League and Mukti Bahini secessionists,[38] whose declared aim after 26 March 1971 became the establishment of an independent state of Bangladesh in place of East Pakistan. Excerpts from Azam's speeches after 25 March 1971 used to be published in the mouthpiece of Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami named, The Daily Sangram. On 20 June 1971, Azam reaffirmed his support for the Pakistani army by citing that 'the army has eradicated nearly all criminals of East Pakistan'.[38]

East Pakistan Central Peace Committee

[edit]During the war of 1971, Azam played a central role in the formation of East Pakistan Central Peace Committee on 11 April 1971.[39][40] Azam was one of the founding members of this organization.[39]

The Peace Committee served as a front for the army, informing on civil administration as well as the general public. They were also in charge of confiscating and redistribution of shops and lands from Hindu and pro-independence Bengali activists, mainly relatives and friends of Mukti Bahini fighters. The Shanti Committee has also been alleged to have recruited Razakars.[41] The first recruits included 96 Jamaat party members, who started training in an Ansar camp at Shahjahan Ali Road, Khulna.[42][43]

During Azam's leadership of Jamaat-e-Islami, Ashraf Hossain, a leader of Jamaat's student wing Islami Chhatra Sangha, created Al-Badr in Jamalpur on 22 April 1971. On April 1971, Azam and Motiur Rahman Nizami led demonstrations denouncing the independence movement as an Indian conspiracy.[44] Azam denied the association between the Peace Committee and Razakar Bahini even though they were formed by the government and headed by Pakistani army general Tikka Khan.[37]

During the war, Azam travelled to West Pakistan at the time to consult Pakistani leaders.[45] He declared that his party (Jamaat) is trying its best to curb the activities of pro-independence "miscreants".[46] He took part in meetings with General Yahya Khan, the then military strongman of Pakistan and other military leaders to organize the campaign against Bangladeshi independence.[45]

Foreign affairs

[edit]On 12 August 1971, Azam declared in a statement published in the Daily Sangram that "the supporters of the so-called Bangladesh Movement are the enemies of Islam, Pakistan, and Muslims".[47] He also called for an all out war against India.[48] He called for the annexation of Assam.[49]

Azam was the prime standard-bearer who presented the blueprint of the killing of the intellectuals during a meeting with Rao Farman Ali in early September 1971.[50] With his help, Pakistani Army and the local collaborators executed the killing of the Bengali intellectuals on 14 December 1971.

On 20 June 1971, Azam declared in Lahore that the Hindu minority in East Pakistan, under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, are conspiring to secede from Pakistan.[46] On 12 August 1971, Azam again declared in a statement published in the Daily Sangram that "the supporters of the Bangladesh Movement are the enemies of Islam, Pakistan, and Muslims".[47] On his part, Azam denied all such accusations and challenged the validity of some and gave reasons to justify others.[51] However, he later admitted that he was on the list of collaborators of the Pakistani army, but denied he was a war criminal.[40] In 2011, Azam denied such sentiments and claimed that the Pakistani government censored The Daily Sangram.[37]

1971 election

[edit]The military junta of General Yahya Khan decided to call an election in an effort to legitimize themselves. On 12 October 1971, Yahya Khan declared that an election will be held from 25 November to 9 December. Azam decided to take part in this election.[52][better source needed] According to a government declaration of 2 November, 53 candidates would be elected without competition. Jamaat received 14 of the uncontested seats.[53]

In 2011, Azam claimed that the reason for his opposition to the creation of Bangladesh were only political and he denied participation in any crime.[37] He also disliked Indian involvement and influence in Bangladeshi internal society and economic matters.[37]

Leader of Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh

[edit]The government of newly independent Bangladesh, banned Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami and cancelled Azam's citizenship, along with that of Nurul Amin, the former prime minister due to their opposition to Bangladesh's independence.[54][37] Following the independence of Bangladesh, he migrated to Pakistan.[37] Azam lived in exile in London until he was allowed to return home in 1978.[30]

Jamaat-e-Islami became active again when Ziaur Rahman became president after a coup in 1975 and lifted the previous ban on religious parties. Zia removed secularism in the constitution, replacing it with Islamic ideals, further clearing the way for Jamaat-e-Islami to return to political participation.[30] In 1978, Azam returned to Bangladesh on a Pakistani passport with a temporary visa, and stayed as a Pakistani national until 1994 even after his visa expired; he refused to leave the country and continued to live in Bangladesh.[55][56] His stay was however unwelcome in Bangladesh and he was beaten by an angry violent mob near Baitul Mukarram while attending a funeral in 1981.[57]

In the 1980s and early 1990s, Azam was particularly critical of the military rule under Hussain Muhammad Ershad after he seized power in a bloodless coup in 1982 and Jamaat-e-Islami took part in demonstrations and strikes as well as other opposition parties such as the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). He proposed a caretaker government system to facilitate free and fair elections, which was adopted in 1990. In the 1991 Bangladeshi general election, Jamaat-e-Islami won 18 seats and its support allowed BNP to form a government.[30]

During this time, he acted unofficially as the Ameer (leader) of Jamaat-e-Islami until 1991, when he was officially elected to the post. This led the government arresting him and an unofficial court called "The People's Court" was established by the civilians such as Jahanara Imam to try alleged war criminals and anti-independence activists. Imam held a symbolic trial of Azam where thousands of people gathered and gave the verdict that Azam's offences committed during the war deserve capital punishment.[58] In 1994, he fought a lengthy legal battle which resulted in the Supreme Court of Bangladesh ruling in his favor and restoring his nationality.[30]

In the 1996 election, Jamaat won only three seats and most of their candidates lost their deposits.[59] Azam announced his retirement from active politics in late 2000. He was succeeded by Motiur Rahman Nizami.[60]

War crimes trial

[edit]Arrest and incarceration

[edit]On 11 January 2012, Azam was arrested on charges of committing crimes against humanity and peace, genocide and war crimes in 1971 by the International Crimes Tribunal. His petition for bail was rejected by the ICT, and he was sent to Dhaka Central Jail. However, three hours later he was taken to the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU) hospital for a medical check-up because of his health issues.

According to The Daily Star, Azam was allowed to remain in a hospital prison cell despite being declared fit for trial by a medical team on 15 January.[61][62] The same paper later acknowledged that he had been placed there because to his "ailing condition".[63]

Azam's health was deteriorating rapidly after being imprisoned.[64] His wife, Syeda Afifa Azam reported in several newspapers as being shocked about Azam's treatment and stated that he was very weak and had lost 3 kilograms in a month due to malnutrition.[38] She described his treatment as "a gross violation of human rights" even though he was kept in a hospital prison cell.[65][66]

Azam's wife complained that he had been denied proper family visits and access to books, saying that this amounted to "mental torture".[67] The Daily Star reported that Azam's wife and his counsels were allowed to meet him on 18 February.[63]

On 25 February 2012, The Daily Star further reported that Azam's nephew was denied a visit shortly before he was about to enter hospital prison. This was despite the application for the visit being first approved.[68]

During the trial, former advisor to the Caretaker government of Bangladesh, human rights activist and witness for the prosecution, Sultanaa Kamal said:

In brutality, Ghulam Azam is synonymous with German ruler Hitler who had influential role in implementation and execution of genocide and ethnic cleansing.[69]

In response to this statement, the defence counsel pointed out that the comparison was a fallacy and "fake with malicious intention" as Hitler held state power, which Azam did not and that in 1971, General Tikka Khan and Yahya Khan held state power.[70] Prosecutor of ICT, Zead-Al-Malum said:

He was the one making all the decisions, why would he need to be on any committee? Being Hitler was enough for Hitler in World War II.

Islamic activists from different countries expressed their concerns for Mr. Azam. The International Union of Muslim Scholars, chaired by Yusuf al-Qaradawi called the arrest "disgraceful", and called on the Bangladesh government to release him immediately, stating that "the charge of Professor Ghulam Azam and his fellow scholars and Islamic activists of committing war crimes more than forty years ago is irrational and cannot be accepted".[71]

The judicial process under which Azam was on trial was criticized by international organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.[72][73]

Verdict

[edit]Azam was convicted of war crimes during the Bangladesh Liberation War by the International Crimes Tribunal.[74] The charges against Azam were torturing and the killings of a police officer Shiru Mia and three others. He was found guilty on all five charges and was sentenced to 90 years in prison.[citation needed]

The judges unanimously agreed that Azam deserved capital punishment but was given a lenient punishment because of his aging and poor health condition.[74][75]

Responses

[edit]Azam had always maintained that he never participated in any crimes but tried "to help people as much as he could."[37] In a press release, Jamaat's Acting Secretary General Rafiqul Islam rejected the International Crimes Tribunal's verdict against Azam by stating his conviction "nothing but a reflection of what AL-led 14-party alliance leaders had said against him Ghulam Azam in different meetings".[76] The Daily Amar Desh said that the evidence presented before the court against Ghulam Azam consisted of newspaper clippings published during 1971 and not independently proved.[77]

Death

[edit]Ghulam Azam died after suffering a stroke on 23 October 2014 at 10:10 PM at Bangladesh Medical University while serving jail sentences for crimes against humanity during the Bangladesh Liberation War. His death was reported by Abdul Majid Bhuiyan, director of BMU. Ghulam Azam was put on life support at 8 PM.[78][79] He was also suffering from kidney ailments.[80]

Azam was buried at his family graveyard at Moghbazar, Dhaka on 25 October. His namaz-e-janaza (Islamic funeral prayer) was held at Bangladesh's national mosque Baitul Mokarram, which is still considered one of the largest gatherings at any funeral prayers. Different quarters of the country protested against taking Azam's body to the national mosque.[81]

Family

[edit]His son, Abdullahil Amaan Azmi was a brigadier general in the Bangladesh Army who was dismissed without explanation. He was missing after 2016.[82] In 2022, it was revealed by an investigative report by Netra News that he was detained at a secret prison called Aynaghar, which is controlled by the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence.[83]

In August 2024, after the July Revolution (Bangladesh), he was released from Aynaghar after 9 years of disappearance.[84] Moreover, his dismissal was revoked and he was granted retirement as a Brigadier General, with the benefits of the rank.[85]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Ghulam Azam's Role in Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami". Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Rubin, Barry A. (2010). Guide to Islamist Movements. M.E. Sharpe. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7656-4138-0.

- ^ Fair, C. Christine (2010). Pakistan: Can the United States Secure an Insecure State?. Rand Corporation. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-8330-4807-3.

- ^ Manik, Julfikar Ali; Khan, Mahbubur Rahman (16 July 2013). "Ghulam Azam Deserves death, gets 90 years". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Azam found guilty of Bangladesh war crimes". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Islamist leader found guilty of war crimes". Euronews. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Uddin, Sufia M. (2006). Constructing Bangladesh: Religion, Ethnicity, And Language in an Islamic Nation. University of North Carolina. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8078-3021-5.

- ^ Evans, H. (2001). "Bangladesh: An Unsteady Democracy". In Shastri, A.; Wilson, A. (eds.). The Post-colonial States of South Asia: Democracy, Development and Identity. Palgrave. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-312-23852-0.

- ^ Ahsan, Syed Aziz-al (October 1990). Islamization of the State in a Dualistic Culture: The Case of Bangladesh (PhD). McGill University, Dept of Political Science.

- ^ গোলাম আযমের বিরূদ্ধে ডঃ আনিসুজ্জামান উত্থাপিত অভিযোগপত্র [Allegations against Ghulam Azam submitted by Prof. Anisuzzaman]. Daily Prothom Alo (in Bengali). 14 March 2008.

- ^ Hashmi, Taj I. (2000). Women and Islam in Bangladesh: Beyond Subjection and Tyranny. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-312-22219-2.

He finally won back his citizenship on 22 June 1994, as decided by the Supreme Court ... It may be mentioned here that he had been living in Bangladesh from 1978 to 1994 as a Pakistani national without any valid visa to stay in Bangladesh.

- ^ Hossain, Ishtiaq; Siddiquee, Noore Alam (2004). "Islam in Bangladesh Politics: the role of Ghulam Azam of Jamaat-i-Islaami". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 5 (3): 385. doi:10.1080/1464937042000288688. S2CID 146155342.

- ^ Manik, Julfikar Ali; Sarkar, Ashutosh (12 January 2012). "Ghulam Azam lands in jail". The Daily Star (Bangladesh).

- ^ Sarkar, Ashutosh; Laskar, Rizanuzzaman (13 December 2011). "Ghulam faces 52 charges". The Daily Star (Bangladesh).

- ^ "ICT further denies bail to Ghulam Azam". United News of Bangladesh. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012.

- ^ "Azam found guilty of Bangladesh war crimes". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Islamist leader found guilty of war crimes". Euronews. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ Islam, Udisa (15 July 2013). "Ghulam Azam spared death". Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Manik, Julfikar Ali; Khan, Mahbubur Rahman (16 July 2013). "Ghulam Azam Deserves death, gets 90 years". The Daily Star. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Ahmed, Tanim (15 July 2013). "Prosecution Blamed for Delay". Bdnews24.com. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Azam Conviction Based on Flawed Proceedings". Human Rights Watch. 16 August 2013.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Azam Trial Concerns". Human Rights Watch. 16 August 2013.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Resist pressure to push for death sentences at war crimes tribunal". Amnesty International. 15 February 2013.

- ^ "Bangladesh: Resist pressure to push for hasty death sentences at war crimes Tribunal" (PDF). Amnesty International. 22 February 2013.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam dies". Bdnews24.com. October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Thousands attend funeral for former Bangladesh Islamist leader". Reuters. October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Professor Ghulam Azam A name, A history". Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b sdcuk (18 January 2015). "My Journey Through Life Part 3". Professor Ghulam Azam. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "My Journey Through Life Part 2". Professor Ghulam Azam. 11 January 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hossain, Ishtiaq; Siddiquee, Noore Alam (2004). "Islam in Bangladesh Politics: the role of Ghulam Azam of Jamaat-i-Islaami". Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 5 (3): 385. doi:10.1080/1464937042000288688. S2CID 146155342.

- ^ "Pro-Bangla activist turns anti-Bangladesh". Dhaka Tribune. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "The Rawalpindi Round-Table Conference". Keesing's Record of World Events. Vol. 15, no. 5. Pakistan. May 1969. p. 23353.

- ^ White Paper on The Crisis in East Pakistan. Islamabad: Ministry of Information and National Affairs. 1971. OCLC 937271.

- ^ White Paper on The Crisis in East Pakistan. Islamabad: Ministry of Information and National Affairs. 1971. pp. 6–8. OCLC 937271.

- ^ "Police accused over rioting", The Guardian, 26 January 1970, pg. 4

- ^ Salik, Siddiq (1977). Witness to Surrender. Dhaka: The University Press Limited. p. 93. ISBN 978-984-05-1373-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Translation of ATN Bangla Interview". Professor Ghulam Azam. 27 December 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ a b c একাত্তরে গোলাম আযমের বিবৃতি [Ghulam Azams speeches in 1971]. Prothom Alo (in Bengali). 11 January 2012. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012.

- ^ a b ঢাকায় নাগরিক শান্তি কমিটি গঠিত (Citizen's Peace Committee formed in Dhaka), Daily Pakistan, 11 April 1971.

- ^ a b "Ghulam Azam was on Peace Committee". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 12 March 2013. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ The Wall Street Journal, 27 July 1971; quoted in the book Muldhara 71 by Moidul Hasan

- ^ Daily Pakistan. 25 May 1971.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Daily Azad. 26 May 1971.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ পাকিস্তানের প্রতি চীনের দৃঢ় সমর্থন রয়েছে [China fully supports Pakistan]. The Daily Sangram (in Bengali). 13 April 1971.

- ^ a b "History speaks up – Julfikar Ali Manik and Emran Hossain". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 27 October 2007.

- ^ a b লাহোরে সাংবাদিক সম্মেলনে অধ্যাপক গোলাম আযম [Prof. Ghulam Azam in a conference at Lahore]. The Daily Sangram (in Bengali). 21 June 1971.

- ^ a b মাওলানা মাদানীর শাহাদত মুসলমানদের সচেতন করার জন্য যথেষ্ট – গোলাম আযম. The Daily Sangram (in Bengali). 12 August 1971.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam calls for an all out war". The Pakistan Observer. 26 November 1971.

- ^ "Pakistan 'Guilty of Genocide': Senator Kennedy's Charge". The Sydney Morning Herald. 18 August 1971. p. 5. Retrieved 10 January 2016 – via The Daily Star (Bangladesh).

- ^ "I Made No Mistake in 1971: Gholam Azam and the Jamaat Polilics". Bichitra. 17 April 1981.

- ^ Azam ATN Bangla Interview, 14th Dec 2011, with Eng Subs Part 2 on YouTube, See video at 2:15 and 3:42.

- ^ Muldhara '71 (মূলধারা '৭১ Mainstream '71) by Moidul Hasan, page. 128, footnote. 177. published by University Press Limited.

- ^ Browne, Malcolm W. (4 November 1971). "53 Pakistan Assembly Seats To Be Filled Without a Vote". International Herald Tribune. p. 5.

Nov 3 ... The Pakistani government announced yesterday that 53 of the National Assembly seats taken away from members of the outlawed Awami League in East Pakistan will be filled without contest ... The party getting the biggest bloc of seats from the 53 ... is the Jamaat-Islami ... to get 14 seats.

- ^ Ahsan, Syed Aziz-al (October 1990). Islamization of the State in a Dualistic Culture: The Case of Bangladesh (PhD). McGill University, Dept of Political Science.

- ^ গোলাম আযমের বিরূদ্ধে ডঃ আনিসুজ্জামান উত্থাপিত অভিযোগপত্র [Allegations against Ghulam Azam submitted by Prof. Anisuzzaman]. Daily Prothom Alo (in Bengali). 14 March 2008.

- ^ Hashmi, Taj I. (2000). Women and Islam in Bangladesh: Beyond Subjection and Tyranny. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-312-22219-2.

He finally won back his citizenship on 22 June 1994, as decided by the Supreme Court ... It may be mentioned here that he had been living in Bangladesh from 1978 to 1994 as a Pakistani national without any valid visa to stay in Bangladesh.

- ^ "War criminal Ghulam Azam buried". bdnews24.com. 25 October 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Manik, Julfikar Ali (12 May 2009). "Focus back on, 8yrs after". The Daily Star (Bangladesh).

- ^ Nohlen, Dieter; Grotz, Florian; Hartmann, Christof (2001). Elections in Asia and the Pacific: A Data Handbook: Volume I: Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia. Oxford University Press. p. 525. ISBN 978-0-19-153041-8.

- ^ "Prof. Ghulam Azam Retires". Islamic Voice. Archived from the original on 6 March 2001.

- ^ "Hospital stay not needed". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 15 January 2012.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam lands in jail". bdnews24.com. 11 January 2012.

- ^ a b "Counsels visit Ghulam Azam". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 19 February 2012.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam's counsels prefer ICT-2". Bdnews24.com. 30 May 2012.

- ^ স্বামীর জীবন নিয়ে আমি শঙ্কিত : সৈয়দা আফিফা আযম [I am in fear of my husband's life: Syeda Afifa Azam]. Daily Naya Diganta (in Bengali). 27 January 2012. Archived from the original on 30 January 2012.

- ^ অধ্যাপক গোলাম আযমের [Professor Ghulam Azam has lost 3 kg in weight]. The Daily Sangram (in Bengali). 5 February 2012. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013.

- ^ গোলাম আযমকে 'প্রিজন সেল'এ মানসিকভাবে নির্যাতন করা হচ্ছে -মিসেস আফিফা আযম [Ghulam Azam is being mentally tortured in his prison cell – Mrs Afifa Azam]. The Daily Sangram (in Bengali). 12 February 2012. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Azam was held in solitary confinement and was allowed a visit of 30 minutes per week by 3 close relatives only. Applications for visits are required to be made in advance and require approval.

- ^ "Wife, son meet Ghulam Azam". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 21 January 2012.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam synonymous with Hitler: Sultana Kamal". United News of Bangladesh. 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ "13 Sep 2012: Azam 3rd witness cross exam day 3". David Bergman. 20 November 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ^ الإتحاد يندد بإعتقال الحكومة البنغالية المفكرين الإسلاميين ويطالب بإطلاق سراحهم [The Union condemns the arrest of Professor Ghulam Azam and other thinkers by the Bangladeshi government]. International Union of Muslim Scholars (in Arabic). 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Detention of accused unlawful". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 16 February 2012.

- ^ Adams, Brad (1 February 2013). "Bangladesh: Government Backtracks on Rights". Human Rights Watch.

- ^ a b Manik, Julfikar Ali; Khan, Mahbubur Rahman (16 July 2013). "Ghulam Azam Deserves death, gets 90 years". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ Ahmed, Tanim (15 July 2013). "Prosecution Blamed for Delay". Bdnews24.com. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- ^ "Jamaat rejects judgment". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 16 July 2013.

- ^ গোলাম আযমের প্রত্যক্ষ সম্পৃক্ততা প্রমাণ হয়নি: ফজলে কবির [Ghulam Azam's direct involvement has not been proven: Fazle Kabir]. Amar Desh (in Bengali). 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013.

- ^ "War criminal Golam Azam dies". Daily Prothom Alo. 23 October 2014. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- ^ Julfikar Ali Manik, Moniruzzaman Uzzal (23 October 2014). "War criminal Ghulam Azam dies". Dhaka Tribune. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam on life support". Bdnews24.com. 23 October 2014.

- ^ "Ghulam Azam buried". The Daily Star (Bangladesh). 25 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ "Bangladesh police accused of abducting ex-JI chief's son". Dawn. Agence France-Presse. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "Secret prisoners of Dhaka". Netra News. 14 August 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ আট বছর পর ফিরলেন আমান আযমী ও আরমান. Prothom Alo (in Bengali). 6 August 2024. Retrieved 18 August 2024.

- ^ "Army revokes Brig Gen Azmi's dismissal order, grants retirement with benefits". The Business Standard. 27 December 2024.

Ghulam Azam

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Family and Upbringing

Ghulam Azam was born on November 7, 1922, in the Shah Saheb Bari, the maternal family home in Laxmibazar, Dhaka, then part of the Bengal Presidency in British India.[1] He was the eldest son of Sheikh Ghulam Kabir, a local religious scholar (maulana), and Sayeda Ashrafunnisa.[1] [8] His paternal lineage traced to the Sheikh family of Birgaon village in Nabinagar sub-district, Brahmanbaria district, where the ancestral home, known as Maulvi Bari, had long served as a center for Islamic scholarship across generations.[1] [8] Azam's early childhood was steeped in a devout Muslim environment, with his father's role as a religious figure providing direct exposure to Islamic teachings and Quranic studies from a young age.[1] His maternal grandfather, Shah Sayed Abdul Monaem, held the position of Shah Shaheb, a respected spiritual leader in the community, further embedding religious observance and scholarly traditions into family life.[1] This rural-rooted yet urban-influenced upbringing in Bengal emphasized piety, moral discipline, and community leadership, fostering Azam's initial grounding in Islamist values amid the socio-religious fabric of pre-Partition Muslim society.[8] As tensions mounted in Bengal leading to the 1947 Partition, Azam's family navigated the era's communal divisions and nationalist stirrings, which subtly shaped his awareness of Muslim identity and self-determination in a Hindu-majority region.[9] These formative experiences in a middle-class household of religious erudition prioritized ethical Islamic conduct over secular influences, laying the groundwork for his lifelong commitment to faith-based reform without formal political engagement at this stage.[8]Academic Pursuits and Early Influences

Ghulam Azam completed his early education at a local madrasa in his village before pursuing secondary schooling in Dhaka, where he passed the Higher Secondary Certificate examination in 1944, securing the 10th position in merit.[1] He subsequently enrolled at Dhaka University, earning a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1946 with subjects including Arabic, English, and political science, followed by a Master of Arts in political science in 1948.[1] [10] [11] Following his postgraduate studies, Azam took up a teaching position in 1950 as a lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Government Carmichael College in Rangpur, advancing to professor by 1955.[12] [11] [13] This five-year tenure honed his analytical expertise in governance structures, state ideologies, and political theory through classroom instruction and scholarly engagement.[1] During his time at Carmichael College, Azam encountered the writings of Abul A'la Maududi, the founder of Jamaat-e-Islami in India, whose expositions on Islamic governance and societal reform laid foundational intellectual groundwork for his later Islamist worldview, independent of organizational commitment at that stage.[14] [15]Entry into Islamist Politics

University Activism and Initial Organizing

Ghulam Azam enrolled at Dhaka University in 1944 following his Intermediate examinations, pursuing studies in Arabic, English, and Political Science for his B.A. Honors, which he completed in 1946, followed by an M.A. in Political Science in 1948.[1] During this time, he rapidly rose in campus politics, becoming Assistant Secretary of the East Pakistan Cultural Union for the 1945–1946 term, where he focused on promoting cultural awareness among students in the lead-up to partition.[2][3] Azam's prominence grew amid the turbulent context of India's partition and Pakistan's creation on August 14, 1947, as he advocated for Muslim student interests in the emerging state, emphasizing unity against communal divisions inherited from colonial rule.[3] Elected General Secretary of the Dhaka University Central Students' Union (DUCSU) for 1947–1948 and re-elected for 1948–1949—securing the highest votes in the initial contest—he organized student initiatives to address post-partition challenges, including cultural and linguistic recognition within an Islamic framework.[12][2] In 1948, as DUCSU leader, he spearheaded the submission of a memorandum to Pakistan's Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan demanding Bengali's status as a state language alongside Urdu, marking an early instance of coordinated student advocacy for regional Muslim Bengali identity.[1] These efforts positioned Azam against the backdrop of competing ideologies on campus, where secular leftist groups, often skeptical of Pakistan's religious foundations, vied for influence among fewer Muslim adherents.[16] His organizing prioritized empirical concerns like linguistic equity and cultural preservation over purely ethnic divisions, drawing on observations of colonial-era fragmentations that had weakened Muslim cohesion.[3] Sources from Azam's supporters highlight his role in fostering student groups aligned with Islamic principles, though mainstream accounts, potentially influenced by later political animosities, emphasize his general leadership without detailing ideological specifics.[2]Joining and Rising in Jamaat-e-Islami

Ghulam Azam formally affiliated with Jamaat-e-Islami in 1954, aligning with the organization's Islamist vision inspired by its founder Abul A'la Maududi.[17] [18] Shortly after joining, he established and led the party's inaugural unit in Rangpur as its founder-president, leveraging his prior experience in student organizations to recruit members and build grassroots infrastructure in the region.[1] This role highlighted his early organizational prowess, as he expanded local chapters amid the challenges of operating in post-partition Pakistan, where Islamist groups sought to promote ethical governance rooted in Islamic principles.[17] Azam's rhetorical effectiveness and tactical insight facilitated swift advancement within the hierarchy; within three years, in 1957, he ascended to the position of Secretary General for the East Pakistan branch, overseeing coordination and propagation efforts.[2] [18] His tenure involved adapting Maududi's transnational Islamist framework to the bifurcated Pakistani polity, stressing that societal moral erosion—manifest in secular influences and regional disparities—directly precipitated political instability and the need for unified Islamic revivalism as a stabilizing force.[19] This ideological emphasis informed Jamaat-e-Islami's advocacy for a centralized ethical order over fragmented ethno-linguistic demands. His activism drew repression under President Ayub Khan's military administration; in 1964, Azam was imprisoned for several months due to his role in party mobilization against the regime's secular modernization policies, which Jamaat-e-Islami critiqued as undermining Islamic sovereignty.[2] [20] These detentions underscored his commitment to organizational resilience, as he continued to mentor cadres upon release, fortifying the party's presence in East Pakistan through disciplined recruitment and ideological training.[14]Stance and Activities during the 1971 War

Ideological Objections to Bengali Secessionism

Ghulam Azam, serving as Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami in East Pakistan from 1969, articulated opposition to Bengali secessionism by emphasizing the primacy of Islamic unity over ethnic or linguistic divisions, positing that a fragmented Pakistan would undermine the Muslim ummah's strategic position vis-à-vis Hindu-majority India. He argued that secessionist tendencies, driven by regional nationalism, risked exposing East Pakistan to Indian influence and dominance, as a divided Muslim polity lacked the collective strength to counter historical patterns of Hindu expansionism observed in pre-partition India. This stance reflected a causal realism wherein religious solidarity served as the foundational bulwark for political sovereignty, empirically grounded in the 1947 partition's success in carving out a Muslim homeland.[21][22] In statements from 1969 to 1970, Azam rejected the Awami League's Six Points autonomy demands—introduced in 1966 and gaining traction post-1970 elections—as a "secessionist blueprint" that eroded Islamic governance principles in favor of secular federalism, potentially paving the way for Bengali separatism and the dilution of sharia-based unity across Pakistan's wings. He warned that such demands prioritized parochial interests over pan-Islamic cohesion, forecasting that they would empower secular nationalists and Indian-aligned elements, thereby fracturing the ideological bonds forged at Pakistan's inception. Azam's writings, including his 1978 pamphlet Islamic Unity and Islamic Movement, reinforced this by advocating transnational Muslim solidarity as antidote to nationalist fissures.[21][23] Azam invoked historical Muslim unity under Mughal rule over Bengal—spanning from 1576 to 1757, when Islamic governance integrated diverse regions without ethnic fragmentation—to illustrate that religious affinity had empirically sustained political resilience against non-Muslim adversaries, contrasting it with the divisive outcomes of linguistic chauvinism in contemporary East Pakistan. This first-principles approach critiqued Bengali nationalism as empirically prone to external subversion, given India's proximity and demographic superiority, urging instead a federated Islamic Pakistan to preserve causal chains of Muslim self-determination.[21]Leadership in Anti-Independence Efforts

As Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami's East Pakistan branch from 1969 to 1971, Ghulam Azam led the party's ideological and organizational opposition to Bengali secessionism, emphasizing the preservation of Pakistan's unity as essential to Muslim solidarity.[6] He coordinated public campaigns, including speeches that urged resistance to the independence movement and framed its proponents as adversaries to Islamic principles.[6] These rhetorical efforts aimed to rally Jamaat-e-Islami cadres—estimated in the thousands across urban centers—toward unwavering loyalty to Islamabad, countering the separatist narrative post the Awami League's landslide in the December 1970 elections.[24] Azam critiqued the post-election deadlock, attributing it to East Pakistan's demands for autonomy that risked national fragmentation, while advocating for negotiated reforms within a federal structure to avert breakup.[25] On April 6, 1971, he met with Lieutenant General Tikka Khan, the Pakistani Army's commander in East Pakistan, to lobby for concessions addressing Bengali grievances without conceding to secessionist pressures.[26] This diplomatic engagement reflected his strategy of influencing Pakistani civilian and military leadership to prioritize unity through political accommodations, such as enhanced provincial powers, over military escalation.[24] In Jamaat-e-Islami publications and addresses during early 1971, Azam articulated causal concerns that secession would engender chronic instability, drawing parallels to vulnerabilities in other post-colonial Muslim-majority divisions where fragmented states faced external predation and internal discord.[21] His arguments rooted in first-principles of Islamic geopolitical realism posited that preserving Pakistan's territorial integrity was vital to countering Hindu-majority India's regional dominance and maintaining a viable Muslim polity.[6] These positions mobilized ideological commitment among followers, positioning Jamaat-e-Islami as a bulwark against what Azam described as self-destructive regionalism.[24]Specific Organizational Roles

Ghulam Azam held the position of Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami in East Pakistan from 1967 until 1971, overseeing the party's administrative and coordinating functions during the onset of the Bangladesh Liberation War.[1] [2] In early April 1971, Azam participated as a founding member and key organizer in the establishment of the East Pakistan Central Peace Committee on 10 April, an entity formed to collaborate with Pakistani authorities in restoring public order, suppressing secessionist activities, and facilitating administrative control amid the conflict.[24] [27] As Ameer, Azam directed Jamaat-e-Islami's support for the Razakar paramilitary units, officially gazetted on 2 August 1971 as auxiliary forces to aid internal security, with party members recruited for roles in vigilance, intelligence gathering, and logistical assistance rather than frontline combat, per organizational directives.[24] [28] Azam engaged in coordination efforts with Pakistani military leadership, including meetings with Lieutenant General Tikka Khan in April 1971 to align Islamist organizational resources with efforts to preserve national unity.[26] He also traveled during the war period to West Pakistan, where he continued advocacy for unified Pakistan through interactions with political and military figures.[29]Allegations of War Crimes Involvement

Ghulam Azam faced allegations from the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) of Bangladesh for planning, incitement, conspiracy, and complicity in crimes against humanity during the 1971 Liberation War, including aiding the Pakistani army in systematic killings, rapes, and village burnings through Jamaat-e-Islami's organizational networks.[11] As the acting Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami, prosecutors claimed Azam directed the formation of Peace Committees across East Pakistan, which collaborated with Pakistani forces to identify and target Bengali nationalists, resulting in widespread atrocities such as the massacre of civilians in various districts.[30] These committees, often led by JI members, were accused of mobilizing local collaborators, including proto-Razakar units, to abet military operations that led to an estimated 3 million deaths and hundreds of thousands of rapes, with Azam's speeches purportedly inciting members to suppress the independence movement violently.[5] The indictment framed charges against Azam related to specific events, including the orchestration of attacks on Hindu minorities and intellectuals, with claims tying him to 61 counts initially, though the tribunal convicted on five involving conspiracy and abetment in crimes like the December 1971 intellectual purges aimed at decapitating Bengali leadership.[7] Prosecution evidence included witness accounts of JI-led operations in northern regions, such as Rangpur, where survivors testified to Razakar forces—recruited and directed by JI under Azam's influence—conducting raids that burned villages and executed suspected Mukti Bahini supporters, with one witness describing forced conversions and torture at gunpoint in nearby areas as part of broader anti-secessionist campaigns.[31] Another testimony highlighted Azam's role in coordinating anti-independence propaganda and logistics that facilitated Pakistani army sweeps, contributing to documented massacres in JI strongholds.[32] Allegations extended to Azam's direct appeals for unity with Pakistan, which prosecutors argued amounted to incitement for genocide, drawing on archival speeches and organizational directives from JI's 1971 activities that allegedly planned the suppression of Bengali secessionism through auxiliary forces' participation in atrocities.[30] Survivor testimonies detailed JI-orchestrated abductions and killings in Rangpur and surrounding areas, with claims of over 10,000 deaths attributed to local Peace Committee and Razakar actions under central JI guidance during operations from March to December 1971.[25] These charges portrayed Azam as a key architect in leveraging Islamist networks to support Pakistani counterinsurgency, focusing on empirical instances of complicity without addressing post-war outcomes.Defenses against Collaboration Charges

Ghulam Azam and his defenders maintained that, as a political figure heading Jamaat-e-Islami, he lacked any formal military command or operational control over auxiliary forces such as the Razakars, Al-Badr, or Al-Shams during the 1971 conflict, with authority residing instead under Pakistani government ordinances like the Razakar Ordinance of September 7, 1971, and direct military oversight.[33] They argued his influence was ideological and rhetorical, centered on advocating for Pakistan's territorial integrity against perceived Indian-backed secessionism, rather than endorsing or directing genocidal acts, and pointed to the absence of evidence showing him issuing orders for atrocities.[13] Defenders highlighted Azam's efforts through the Central Peace Committee, formed on April 9, 1971, to restore civil order, mediate civilian complaints against army actions, and counter "miscreants" associated with the Mukti Bahini, whom they portrayed as engaging in terrorism and targeted killings of non-secessionist Bengalis and Urdu-speakers prior to and during the war.[33] Azam personally claimed to have intervened with Pakistani officials, including General Tikka Khan, to curb army excesses, citing instances where he facilitated the release of detainees and publicly called for restraint in speeches, such as one on August 14, 1971, opposing military overreach while prioritizing national unity.[34] Jamaat-e-Islami records and defense exhibits, including speeches and committee statements, were presented as evidence of initiatives to mitigate violence by promoting dialogue and administrative cooperation, framing such actions as defensive responses to insurgency rather than collaborative aggression.[33] Critics of the collaboration charges, including Azam's supporters, contended that prosecutions were empirically selective, overlooking the Pakistani army's primary responsibility for mass casualties—as detailed in the Hamoodur Rahman Commission's findings on widespread military misconduct—while ignoring documented reprisal killings by Mukti Bahini elements and Awami League affiliates against suspected collaborators and Bihari communities in late 1971 and early 1972, estimated in the tens of thousands.[35] Azam argued that initial post-war amnesties granted by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, including forgiveness for Pakistani officers, undermined retrospective claims of universal criminality, portraying the charges as politically motivated rather than rooted in verifiable command culpability.[34]Leadership of Jamaat-e-Islami in Independent Bangladesh

Re-establishing the Party Post-1971

Following Bangladesh's independence on December 16, 1971, Jamaat-e-Islami was promptly banned under the 1972 Constitution (Article 38), which prohibited religion-based political parties, owing to the organization's opposition to Bengali secession during the war.[24] Ghulam Azam, who had led the party's East Pakistan branch, fled to Pakistan amid purges targeting perceived collaborators by the Awami League government, which also stripped citizenship from several JI leaders.[24] [36] From exile, Azam directed the maintenance of underground networks within Bangladesh, where surviving cadres operated covertly through informal cells and personal contacts to preserve organizational continuity despite the ban and surveillance.[24] These efforts focused on low-profile survival rather than overt activity, evading arrests and allowing latent structures to endure until political opportunities arose.[37] The shift came after Ziaur Rahman's military coup in August 1975 and his consolidation as president; by 1976, his regime began permitting JI to resume limited activities as a counterweight to Awami League dominance, with fuller rehabilitation via the 1977 Fifth Amendment, which excised secularism from constitutional principles and enabled religious parties' legalization.[24] [38] Azam leveraged these changes through alliances with Zia's Bangladesh Nationalist Party, securing his return from exile in 1978 to lead the revival openly.[24] Under Azam's direction, JI prioritized grassroots da'wah (Islamic propagation) to rebuild membership, emphasizing ethical reforms and moral education in mosques, madrasas, and community circles to address perceived post-war secular drift and societal disarray from independence-era upheavals.[24] This strategy expanded influence incrementally among rural and urban Muslims, fostering loyalty through non-political welfare and indoctrination networks before formal electoral engagement.[24]Electoral Strategies and Opposition Dynamics

Under Ghulam Azam's leadership as Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh from 1969 until 2000, the party emphasized pragmatic electoral alliances with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) to amplify its influence, given JI's inability to secure a majority independently. In the February 27, 1991, general election—the first multiparty vote following the ouster of military rule—JI contested 210 seats and won 18, providing crucial support to the BNP's 140 seats in forming a coalition government that ousted the Awami League.[39][40] This breakthrough represented JI's transition from a banned post-independence organization to a parliamentary force, with Azam coordinating seat-sharing to maximize gains in rural and conservative constituencies.[39] Azam directed sharp opposition against General Hussain Muhammad Ershad's military regime (1982–1990), joining BNP- and Awami League-led coalitions in mass protests that escalated into the 1990 uprising, forcing Ershad's resignation on December 6. He proposed a non-partisan caretaker government system in the mid-1980s to guarantee impartial elections, decrying Ershad's martial law and secular-leaning policies as antithetical to ethical, Islamic-inspired governance capable of curbing endemic corruption.[41][1][42] Facing Sheikh Hasina's Awami League government after its 1996 victory, Azam repositioned JI within opposition dynamics by forging the 1999 four-party alliance with the BNP, which critiqued the regime's authoritarian tendencies and advocated systemic reforms, including anti-corruption frameworks drawing on Islamic moral principles over secular models. This coalition strategy, yielding JI's participation in the 2001 landslide (though post-Azam's formal tenure), underscored his role in sustaining JI's relevance as a minority partner leveraging ideological appeals to challenge ruling secularism.[43][41]Promotion of Moderate Islamist Ideology

Ghulam Azam emphasized Wasatiyah, the Quranic principle of moderation interpreted from Surah Al-Baqarah 2:143 as positioning Muslims as the "middle community," to advocate for a balanced Islamist framework in Bangladesh that integrated Sharia principles with pragmatic governance, steering clear of both authoritarian theocracy and unbridled secularism.[44] In his da'wah efforts and leadership of Jamaat-e-Islami from 1991 to 2000, Azam applied this concept across preaching, legal edicts, and societal reform, promoting an adaptive interpretation of Abul A'la Maududi's foundational ideas tailored to Bangladesh's multicultural and post-colonial realities, where Islamist revivalism focused on gradualist political participation rather than revolutionary upheaval.[45] Azam's intellectual output positioned Jamaat-e-Islami as a reformist entity grounded in Quranic emphases on justice (adl) and equity, countering perceptions of extremism by advocating non-violent pathways to societal Islamization through education and ethical politics.[44] He critiqued radical deviations from mainstream Sunni orthodoxy, urging party members to embody moderation in responses to secular challenges and militant fringes, as evidenced in his directives for disciplined, issue-based electoral engagement that prioritized consensus-building over confrontation.[46] Under Azam's stewardship, Jamaat-e-Islami implemented social welfare initiatives as tangible expressions of moderate ideology, including the establishment of mass education centers, mosque-based community programs, Islamic cultural hubs, and scholarship-funded schools targeting impoverished families to combat ignorance and prejudice.[46] These efforts, aligned with al-Wasatiyah's balanced approach, aimed to foster human development and religiosity without coercion, distinguishing the party from radical groups by emphasizing democratic participation, human rights advocacy, and poverty mitigation as corollaries to Islamic ethics, thereby building grassroots legitimacy through verifiable service delivery post-1979 party resurgence.[46]Prosecution under the International Crimes Tribunal

Context of Tribunal Establishment

The International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) was formally re-established on March 25, 2010, by an ordinance issued under the Awami League government led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, amending the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act of 1973 to facilitate prosecutions for atrocities during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War.[47] This revival addressed long-standing public demands for accountability, but occurred nearly four decades after the events, raising questions about the empirical feasibility of evidence preservation and witness reliability given the passage of time and potential political influences on memory and documentation.[48] The 1973 Act itself had lain largely dormant since its original promulgation shortly after independence, with minimal prior enforcement despite initial intentions to hold trials.[49] The tribunal's creation aligned with key pledges in the Awami League's 2008 election manifesto, which committed to arranging trials for 1971 war criminals as a core promise following the party's victory in the December 2008 parliamentary elections that brought Hasina to power in January 2009.[48] Proponents framed it as fulfilling historical justice imperatives rooted in the estimated three million deaths and widespread atrocities attributed to Pakistani forces and local collaborators during the nine-month conflict.[50] However, the ICT operated exclusively with domestic judges, prosecutors, and investigators appointed by the government, lacking any international oversight, advisory input, or hybrid structure akin to tribunals in Rwanda or Sierra Leone, which critics argued compromised procedural independence and adherence to global due process standards.[51] Opponents, particularly from the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami (JI)—the latter having served as a significant coalition partner to the BNP in prior elections against the Awami League—alleged that the tribunal's timing and focus reflected partisan motivations to dismantle JI's organizational strength and discredit its leadership ahead of future electoral contests.[24] JI, as a vocal opponent of Bengali secessionism in 1971 and a resilient political force post-independence, had regained influence through alliances that challenged Awami League dominance, prompting claims that the ICT served as a mechanism for selective retribution rather than impartial reckoning.[52] Such assertions highlighted causal linkages between the tribunal's establishment and the Awami League's strategic need to neutralize ideological rivals amid Bangladesh's polarized party system, though government officials maintained it was driven solely by demands for delayed justice.[53]Arrest, Indictment, and Trial Evidence

Ghulam Azam was arrested on January 11, 2012, in Dhaka by Bangladesh's Rapid Action Battalion on allegations of masterminding war crimes during the 1971 Liberation War against Pakistan.[54] At the time of his arrest, Azam was 89 years old and had been living under restrictions since 2005, when the government barred him from politics due to his citizenship status.[54] On May 13, 2012, the International Crimes Tribunal-1 (ICT-1) formally indicted Azam on charges of conspiracy, incitement to murder, planning atrocities, abetment, and complicity in crimes against humanity under sections 3(2), 3(2)(a), 4(1), and 4(2) of Bangladesh's International Crimes (Tribunals) Act of 1973.[55] [11] The indictment centered on Azam's role as ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami in East Pakistan, alleging he coordinated with Pakistani forces to suppress Bengali independence through paramilitary groups and propaganda.[11] The prosecution's case relied primarily on 16 witness testimonies recounting events from 1971, alongside documentary evidence such as newspaper clippings and reports of Azam's public speeches that purportedly urged opposition to independence and justified violence against perceived enemies.[56] [5] Key evidentiary claims included Azam's August 16, 1971, speech quoted in media as calling for resistance against "miscreants," interpreted by prosecutors as incitement to genocide and collaboration with occupation forces.[11] Additional documents highlighted his meetings with Pakistani military officials and directives to party members for auxiliary force recruitment.[30] Trial hearings commenced following the indictment, with prosecution evidence presented through depositions and exhibits alleging Azam's speeches and organizational directives directly contributed to targeted killings and persecution of Hindus and intellectuals.[56] Proceedings advanced to closing arguments by the prosecution in February 2013, focusing on these materials to establish command responsibility without claims of Azam's direct physical involvement in atrocities.[56]Conviction, Sentencing, and Legal Appeals

On July 15, 2013, the International Crimes Tribunal-1 (ICT-1) in Dhaka convicted Ghulam Azam of five counts of crimes against humanity related to the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, including conspiracy, incitement to murder, planning and abetment of killings, and failure to prevent atrocities as a superior authority.[5][7] The tribunal determined that Azam, as Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami, exercised de facto command responsibility over party auxiliaries and peace committees that collaborated with Pakistani forces, leading to systematic violence against civilians.[57] The same verdict imposed a sentence of 90 years' rigorous imprisonment, reflecting the gravity of the charges but accounting for Azam's advanced age of 90, which barred capital punishment under Bangladeshi law at the time.[58][5] Azam was remanded to central jail in Dhaka to serve the term, with the court emphasizing that the punishment aimed to deter future collaboration in genocidal acts.[7] During the trial, Azam consistently denied command responsibility, testifying that he lacked operational control over military actions or auxiliary forces and that Jamaat-e-Islami's role was limited to political opposition against independence.[59] His defense argued that no direct evidence linked him to specific crimes, portraying the charges as politically motivated attributions of collective guilt rather than individual culpability. Azam filed an appeal against the conviction and sentence to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh shortly after the verdict. The court accepted the appeal on October 22, 2014, scheduling oral arguments to commence on December 2, 2014. However, Azam died on October 23, 2014, from respiratory complications while in custody, rendering the appeal moot and leaving the ICT-1 conviction as the final judicial outcome.[61][62]Critiques of Procedural Fairness

Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International raised concerns about the International Crimes Tribunal's (ICT) procedural safeguards, including allegations of witness coaching by prosecutors and restrictions on defense cross-examination. In reports on specific trials, HRW documented instances where witness testimonies appeared coordinated and rehearsed, undermining evidentiary reliability, while the tribunal's rules initially limited defense challenges to prosecution evidence.[63][64] These organizations also criticized the ICT for issuing contempt charges against external critics, such as HRW itself in September 2013 for questioning trial transparency and a journalist in December 2014 for factual reporting on casualty figures, which Amnesty described as chilling effects on oversight and free expression.[65][66] The tribunal's prosecutorial independence was further questioned due to evident government influence in staffing, rule amendments, and timelines. Established under the ruling Awami League administration in 2010, the ICT saw multiple legislative changes to its founding Act during ongoing proceedings—such as provisions for trials in absentia enacted retroactively in 2012—which critics argued served political expediency rather than judicial impartiality.[52][67] HRW noted that prosecutorial appointments and operations lacked insulation from executive pressure, contrasting with international tribunals' emphasis on autonomy to prevent bias.[51] Procedural critiques extended to perceptions of victor's justice, as the ICT focused prosecutions almost exclusively on 1971 collaborators with Pakistani forces while forgoing empirical investigation into atrocities by Mukti Bahini irregulars, such as documented reprisal killings against non-Bengali communities. This selective application, amid the government's historical ties to liberation forces, fueled arguments that the process prioritized political retribution over comprehensive accountability, diverging from standards in hybrid tribunals like those in Sierra Leone or Cambodia that addressed crimes across factions.[68][65]Domestic and International Responses

Following the International Crimes Tribunal's conviction of Ghulam Azam on July 15, 2013, Jamaat-e-Islami organized nationwide hartals, including a dawn-to-dusk shutdown on the verdict day and an extension to July 16, protesting what party leaders described as a politically motivated elimination of opposition figures.[69][70] These actions triggered deadly clashes between supporters and security forces, resulting in multiple fatalities and widespread arson.[7] In contrast, secularist groups aligned with the Shahbag movement rejected the 90-year sentence as unduly lenient, demanding capital punishment for war crimes and vowing sustained protests until harsher penalties were imposed.[71] Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina expressed satisfaction with the outcome, framing it as a step toward accountability for 1971 atrocities.[70] The conviction prompted the Election Commission to cancel Jamaat-e-Islami's registration on August 1, 2013, after the tribunal characterized the party under Azam's leadership as having functioned as a criminal organization during the independence war, effectively barring it from contesting national elections.[72] This deregistration, upheld by the High Court, marked a significant curtailment of the party's political influence, leading to further hartals and violence in early August.[73] Internationally, Human Rights Watch criticized the proceedings as deeply flawed, citing prosecutorial interference, judicial bias, and failure to meet fair trial standards, while taking no position on Azam's guilt.[74] Similar concerns were raised by Western observers and human rights advocates, urging retrials or procedural reforms to ensure due process amid the tribunal's broader operations.[6] These responses contrasted with domestic secularist endorsements, highlighting tensions between local demands for historical justice and global emphases on evidentiary and procedural integrity.Final Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Imprisonment and Health in Later Life

Following his conviction on July 15, 2013, Ghulam Azam, then aged 90, was sentenced to 90 years in prison for crimes against humanity committed during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, with the tribunal opting against the death penalty in consideration of his advanced age and health complications.[7][58] He had been in custody since his arrest on January 11, 2012, during which time bail petitions citing old age, mobility issues requiring a wheelchair, and general health deterioration were repeatedly rejected by the International Crimes Tribunal.[54][75] Azam's pre-trial detention involved initial periods in a jail setting, with medical evaluations occasionally permitting hospital-based custody for treatment, though he was declared fit for proceedings despite ongoing ailments.[76] Post-sentencing, his incarceration continued under prison conditions that drew criticism from supporters for inadequate medical attention to age-related frailties, including cardiovascular vulnerabilities, amid Bangladesh's reported challenges with geriatric care in correctional facilities.[6] No formal transition to house arrest was documented in official proceedings, though his physical limitations necessitated accommodations such as wheelchair access and periodic hospital transfers for monitoring.[77] From custody, Azam maintained ideological positions aligned with Jamaat-e-Islami's Islamist framework, as conveyed through relayed messages and family statements emphasizing opposition to secular nationalism and advocacy for Islamic governance principles, consistent with his pre-incarceration rhetoric.[78] These expressions persisted despite health constraints limiting direct public engagements, underscoring his enduring influence within party circles even under detention.[79]Death, Funeral, and Immediate Aftermath

Ghulam Azam died on October 23, 2014, at the age of 91, from cardiac arrest at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University Hospital in Dhaka, after life support was withdrawn while he was in a coma.[80][81] His funeral prayer was conducted the following day, October 25, at Baitul Mukarram National Mosque in Dhaka, drawing an estimated hundreds of thousands of Jamaat-e-Islami supporters and sympathizers despite heavy security deployments and restrictions imposed by the government on gathering sizes and participant numbers.[82][83] Authorities limited access to the mosque and surrounding areas, citing public order concerns amid ongoing political tensions related to his conviction.[84] Protests erupted during the event, with secular groups and war victims' organizations rallying against the proceedings and demanding stricter controls on the burial, leading to skirmishes between demonstrators, mourners, and security forces in central Dhaka.[85] Jamaat-e-Islami activists reported delays in releasing Azam's body from hospital custody to family control, which fueled accusations of deliberate obstruction by authorities.[84] The funeral proceeded under tight police vigilance, with the body buried at Azimpur Graveyard shortly after prayers.[82]Balanced Assessment of Achievements and Criticisms

Ghulam Azam's tenure as Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami from 1969 onward institutionalized the party as Bangladesh's principal moderate Islamist opposition, emphasizing balanced governance (Wasatiyah) over radicalism and enabling it to function as the largest and most organized Islam-based political entity by the early 2000s.[86] [45] His strategic focus on da'wah expanded Islamic outreach through grassroots networks, fostering education and community engagement that sustained the party's influence amid post-independence bans and exiles.[45] This resistance to secular authoritarianism, particularly against regimes enforcing strict separation of religion and politics, helped preserve Islamic identity in public discourse, contributing causally to Bangladesh's shift from initial secular constitutionalism—amended in 1977 and 1988 to incorporate faith-based elements—toward a hybrid polity blending democratic institutions with state-endorsed Islam.[87] Critics, drawing on tribunal records, link Azam's pro-unified Pakistan stance in 1971—framed as principled opposition to ethnic separatism in favor of Muslim unity—to exacerbation of communal tensions, with party affiliates associated with auxiliary forces that intensified conflict divisions.[25] [88] However, defenses highlight the absence of verified direct command over atrocities, attributing divisions to broader civil war dynamics rather than individual orchestration, especially given international assessments of the 2013 conviction's procedural deficiencies, including restricted defenses and evidentiary gaps.[74] [79] Empirical patterns of post-1971 JI rebuilding under Azam underscore a pivot to electoral moderation, mitigating radical spillover while sustaining opposition to perceived secular overreach. In causal terms, Azam's legacy reflects a trade-off: bolstering Islamist resilience against authoritarian secularism yielded a polity where Islamic provisions temper majoritarian rule, as seen in JI's enduring parliamentary coalitions and madrasa networks influencing policy, yet at the cost of polarized historical memory tied to 1971's unresolved fractures.[89] This duality underscores JI's role in averting full secular hegemony but invites scrutiny over whether anti-separatist ideology foreseeably amplified strife, absent robust evidence of intent beyond ideological fidelity.[88]Personal Life and Intellectual Output

Family and Personal Relationships

Ghulam Azam married Sayeda Afifa Azam, daughter of Maulana Mir Abdus Salam from Bogra, on December 28, 1951.[8][90] The couple had six sons and no daughters, with the family maintaining a low public profile amid Azam's political engagements.[8][4] His eldest son, Abdullahil Amaan Azmi, pursued a military career as a brigadier general before becoming associated with Jamaat-e-Islami activities, reflecting familial continuity in Islamist organizational involvement. Other sons similarly engaged with the party's networks, though details on their individual roles remain sparse in public records. The family supported Azam through relocations following the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, when he fled to Pakistan; his wife and children eventually joined or sustained ties despite the ensuing political exile and asset seizures in Bangladesh.[8] Public accounts of Azam's personal habits emphasize religious observance, including regular congregational prayers and a disciplined, ascetic routine of moderate eating and physical exercise, which contributed to his longevity until age 91.[91] His wife publicly advocated for his health and visitation rights during imprisonment, highlighting strains on family access imposed by legal proceedings.[15] Limited disclosures portray him as softly spoken with a kind demeanor in private interactions.[91]Writings, Speeches, and Scholarly Contributions

Ghulam Azam authored 138 books, predominantly in Bengali, focusing on Islamic theology, politics, and societal reform.[1] These works drew heavily from the intellectual tradition of Abul A'la Maududi, emphasizing the application of Islamic principles to contemporary governance and ethics.[92] His memoir Jibone Ja Dekhlam (What I Saw in Life), serialized in abridged English translations, chronicles his personal encounters with Islamist thought, including detailed reflections on Maududi's writings and the foundational ideology of Jamaat-e-Islami.[19] [92] Azam's scholarly output promoted the Qur'anic principle of Wasatiyah (moderation) as a framework for balanced Islamic activism, adapting it to address modern state-building and da'wah efforts in Bangladesh amid secular influences.[45] [3] As Ameer of Jamaat-e-Islami, he delivered speeches outlining Islamist critiques of secularism, often published in party outlets, advocating for ethical governance rooted in Sharia principles over Western models.[93]References

- https://www.[opendemocracy](/page/OpenDemocracy).net/en/opensecurity/professor-ghulam-azam-flawed-conviction-and-miscarriage-of-justice/