Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Graph drawing

View on Wikipedia

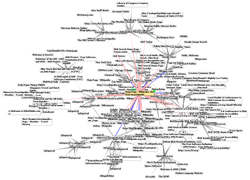

Graph drawing is an area of mathematics and computer science combining methods from geometric graph theory and information visualization to derive two-dimensional (or, sometimes, three-dimensional) depictions of graphs arising from applications such as social network analysis, cartography, linguistics, and bioinformatics.[1]

A drawing of a graph or network diagram is a pictorial representation of the vertices and edges of a graph. This drawing should not be confused with the graph itself: very different layouts can correspond to the same graph.[2] In the abstract, all that matters is which pairs of vertices are connected by edges. In the concrete, however, the arrangement of these vertices and edges within a drawing affects its understandability, usability, fabrication cost, and aesthetics.[3] The problem gets worse if the graph changes over time by adding and deleting edges (dynamic graph drawing) and the goal is to preserve the user's mental map.[4]

Graphical conventions

[edit]

Graphs are frequently drawn as node–link diagrams in which the vertices are represented as disks, boxes, or textual labels and the edges are represented as line segments, polylines, or curves in the Euclidean plane.[3] Node–link diagrams can be traced back to the 14th-16th century works of Pseudo-Lull which were published under the name of Ramon Llull, a 13th century polymath. Pseudo-Lull drew diagrams of this type for complete graphs in order to analyze all pairwise combinations among sets of metaphysical concepts.[5]

In the case of directed graphs, arrowheads form a commonly used graphical convention to show their orientation;[2] however, user studies have shown that other conventions such as tapering provide this information more effectively.[6] Upward planar drawing uses the convention that every edge is oriented from a lower vertex to a higher vertex, making arrowheads unnecessary.[7]

Alternative conventions to node–link diagrams include adjacency representations such as circle packings, in which vertices are represented by disjoint regions in the plane and edges are represented by adjacencies between regions; intersection representations in which vertices are represented by non-disjoint geometric objects and edges are represented by their intersections; visibility representations in which vertices are represented by regions in the plane and edges are represented by regions that have an unobstructed line of sight to each other; confluent drawings, in which edges are represented as smooth curves within mathematical train tracks; fabrics, in which nodes are represented as horizontal lines and edges as vertical lines;[8] and visualizations of the adjacency matrix of the graph.

Quality measures

[edit]Many different quality measures have been defined for graph drawings, in an attempt to find objective means of evaluating their aesthetics and usability.[9] In addition to guiding the choice between different layout methods for the same graph, some layout methods attempt to directly optimize these measures.

- The crossing number of a drawing is the number of pairs of edges that cross each other. If the graph is planar, then it is often convenient to draw it without any edge intersections; that is, in this case, a graph drawing represents a graph embedding. However, nonplanar graphs frequently arise in applications, so graph drawing algorithms must generally allow for edge crossings.[10]

- The area of a drawing is the size of its smallest bounding box, relative to the closest distance between any two vertices. Drawings with smaller area are generally preferable to those with larger area, because they allow the features of the drawing to be shown at greater size and therefore more legibly. The aspect ratio of the bounding box may also be important.

- Symmetry display is the problem of finding symmetry groups within a given graph, and finding a drawing that displays as much of the symmetry as possible. Some layout methods automatically lead to symmetric drawings; alternatively, some drawing methods start by finding symmetries in the input graph and using them to construct a drawing.[11]

- It is important that edges have shapes that are as simple as possible, to make it easier for the eye to follow them. In polyline drawings, the complexity of an edge may be measured by its number of bends, and many methods aim to provide drawings with few total bends or few bends per edge. Similarly for spline curves the complexity of an edge may be measured by the number of control points on the edge.

- Several commonly used quality measures concern lengths of edges: it is generally desirable to minimize the total length of the edges as well as the maximum length of any edge. Additionally, it may be preferable for the lengths of edges to be uniform rather than highly varied.

- Angular resolution is a measure of the sharpest angles in a graph drawing. If a graph has vertices with high degree then it necessarily will have small angular resolution, but the angular resolution can be bounded below by a function of the degree.[12]

- The slope number of a graph is the minimum number of distinct edge slopes needed in a drawing with straight line segment edges (allowing crossings). Cubic graphs have slope number at most four, but graphs of degree five may have unbounded slope number; it remains open whether the slope number of degree-4 graphs is bounded.[12]

Layout methods

[edit]

There are many different graph layout strategies:

- In force-based layout systems, the graph drawing software modifies an initial vertex placement by continuously moving the vertices according to a system of forces based on physical metaphors related to systems of springs or molecular mechanics. Typically, these systems combine attractive forces between adjacent vertices with repulsive forces between all pairs of vertices, in order to seek a layout in which edge lengths are small while vertices are well-separated. These systems may perform gradient descent based minimization of an energy function, or they may translate the forces directly into velocities or accelerations for the moving vertices.[14]

- Spectral layout methods use as coordinates the eigenvectors of a matrix such as the Laplacian derived from the adjacency matrix of the graph.[15]

- Orthogonal layout methods, which allow the edges of the graph to run horizontally or vertically, parallel to the coordinate axes of the layout. These methods were originally designed for VLSI and PCB layout problems but they have also been adapted for graph drawing. They typically involve a multiphase approach in which an input graph is planarized by replacing crossing points by vertices, a topological embedding of the planarized graph is found, edge orientations are chosen to minimize bends, vertices are placed consistently with these orientations, and finally a layout compaction stage reduces the area of the drawing.[16]

- Tree layout algorithms these show a rooted tree-like formation, suitable for trees. Often, in a technique called "balloon layout", the children of each node in the tree are drawn on a circle surrounding the node, with the radii of these circles diminishing at lower levels in the tree so that these circles do not overlap.[17]

- Layered graph drawing methods (often called Sugiyama-style drawing) are best suited for directed acyclic graphs or graphs that are nearly acyclic, such as the graphs of dependencies between modules or functions in a software system. In these methods, the nodes of the graph are arranged into horizontal layers using methods such as the Coffman–Graham algorithm, in such a way that most edges go downwards from one layer to the next; after this step, the nodes within each layer are arranged in order to minimize crossings.[18]

- Arc diagrams, a layout style dating back to the 1960s,[19] place vertices on a line; edges may be drawn as semicircles above or below the line, or as smooth curves linked together from multiple semicircles.

- Circular layout methods place the vertices of the graph on a circle, choosing carefully the ordering of the vertices around the circle to reduce crossings and place adjacent vertices close to each other. Edges may be drawn either as chords of the circle or as arcs inside or outside of the circle. In some cases, multiple circles may be used.[20]

- Dominance drawing places vertices in such a way that one vertex is upwards, rightwards, or both of another if and only if it is reachable from the other vertex. In this way, the layout style makes the reachability relation of the graph visually apparent.[21]

Application-specific graph drawings

[edit]Graphs and graph drawings arising in other areas of application include

- Sociograms, drawings of a social network, as often offered by social network analysis software[22]

- Hasse diagrams, a type of graph drawing specialized to partial orders[23]

- Dessin d'enfants, a type of graph drawing used in algebraic geometry[24]

- State diagrams, graphical representations of finite-state machines[25]

- Computer network diagrams, depictions of the nodes and connections in a computer network[26]

- Flowcharts and drakon-charts, drawings in which the nodes represent the steps of an algorithm and the edges represent control flow between steps.

- Project network, graphical depiction of the chronological order in which activities of a project are to be completed.

- Data-flow diagrams, drawings in which the nodes represent the components of an information system and the edges represent the movement of information from one component to another.

- Bioinformatics including phylogenetic trees, protein–protein interaction networks, and metabolic pathways.[27]

In addition, the placement and routing steps of electronic design automation (EDA) are similar in many ways to graph drawing, as is the problem of greedy embedding in distributed computing, and the graph drawing literature includes several results borrowed from the EDA literature. However, these problems also differ in several important ways: for instance, in EDA, area minimization and signal length are more important than aesthetics, and the routing problem in EDA may have more than two terminals per net while the analogous problem in graph drawing generally only involves pairs of vertices for each edge.

Graph drawing algorithms

[edit]There are many algorithms for graph drawing. Among them are:

- The Reingold-Tilford algorithm for tree drawing.[28]

- Kant's algorithm,[29] which constructs a polyline drawing of a 3-connected planar graph such that the size of the minimal angle among arcs is at least , where d is the maximal node degree; and its generaliztion, that also works well for other planar graphs, by Gutwenger and Mutzel.[30]

- Tamassia's algorithm for minimizing the number of bends in an orthogonal representation of a planar graph.[31]

- The Magnetic Spring Model by Sugiyama and Misue.[32]

Software

[edit]

Software, systems, and providers of systems for drawing graphs include:

- BioFabric open-source software for visualizing large networks by drawing nodes as horizontal lines.

- Cytoscape, open-source software for visualizing molecular interaction networks

- Gephi, open-source network analysis and visualization software

- graph-tool, a free/libre Python library for analysis of graphs

- Graphviz, an open-source graph drawing system from AT&T Corporation[33]

- Linkurious, a commercial network analysis and visualization software for graph databases

- Mathematica, a general-purpose computation tool that includes 2D and 3D graph visualization and graph analysis tools.[34]

- Microsoft Automatic Graph Layout, open-source .NET library (formerly called GLEE) for laying out graphs[35]

- NetworkX is a Python library for studying graphs and networks.

- Tulip,[36] an open-source data visualization tool

- yEd, a graph editor with graph layout functionality[37]

- PGF/TikZ 3.0 with the

graphdrawingpackage (requires LuaTeX).[38] - LaNet-vi, an open-source large network visualization software

- OGDF, an open-source library of C++ data structures and algorithms, mostly for graph drawing[39]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), pp. vii–viii; Herman, Melançon & Marshall (2000), Section 1.1, "Typical Application Areas".

- ^ a b Di Battista et al. (1998), p. 6.

- ^ a b Di Battista et al. (1998), p. viii.

- ^ Misue et al. (1995).

- ^ Knuth (2013).

- ^ Holten & van Wijk (2009); Holten et al. (2011).

- ^ Garg & Tamassia (1995).

- ^ Longabaugh (2012).

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), Section 2.1.2, Aesthetics, pp. 14–16; Purchase, Cohen & James (1997).

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), p 14.

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), p. 16.

- ^ a b Pach & Sharir (2009).

- ^ Grandjean (2014).

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), Section 2.7, "The Force-Directed Approach", pp. 29–30, and Chapter 10, "Force-Directed Methods", pp. 303–326.

- ^ Beckman (1994); Koren (2005).

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), Chapter 5, "Flow and Orthogonal Drawings", pp. 137–170; Eiglsperger, Fekete & Klau (2001).

- ^ Herman, Melançon & Marshall (2000), Section 2.2, "Traditional Layout – An Overview".

- ^ Sugiyama, Tagawa & Toda (1981); Bastert & Matuszewski (2001); Di Battista et al. (1998), Chapter 9, "Layered Drawings of Digraphs", pp. 265–302.

- ^ Saaty (1964).

- ^ Doğrusöz, Madden & Madden (1997).

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), Section 4.7, "Dominance Drawings", pp. 112–127.

- ^ Scott (2000); Brandes, Freeman & Wagner (2014).

- ^ Di Battista et al. (1998), pp. 15–16, and Chapter 6, "Flow and Upward Planarity", pp. 171–214; Freese (2004).

- ^ Zapponi (2003).

- ^ Anderson & Head (2006).

- ^ Di Battista & Rimondini (2014).

- ^ Bachmaier, Brandes & Schreiber (2014).

- ^ Reingold & Tilford (1981).

- ^ Kant (1992).

- ^ Gutwenger & Mutzel (1998).

- ^ Tamassia (1987).

- ^ Sugiyama & Misue (1995).

- ^ "Graphviz and Dynagraph – Static and Dynamic Graph Drawing Tools", by John Ellson, Emden R. Gansner, Eleftherios Koutsofios, Stephen C. North, and Gordon Woodhull, in Jünger & Mutzel (2004).

- ^ "Introduction to graph drawing", Wolfram Language & System Documentation Center, retrieved 2024-03-21

- ^ Nachmanson, Robertson & Lee (2008).

- ^ "Tulip – A Huge Graph Visualization Framework", by David Auber, in Jünger & Mutzel (2004).

- ^ "yFiles – Visualization and Automatic Layout of Graphs", by Roland Wiese, Markus Eiglsperger, and Michael Kaufmann, in Jünger & Mutzel (2004).

- ^ Tantau (2013); see also the older GD 2012 presentation Archived 2016-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fink, Simon D.; Strobl, Andreas (2023). "odgf-python – A Python Interface for the Open Graph Drawing Framework". In Bekos, Michael A.; Chimani, Markus (eds.). Graph Drawing and Network Visualization. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. pp. 258–260. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-49275-4. ISSN 0302-9743.

The Open Graph Drawing Framework (OGDF) is a C++ library that contains a vast amount of algorithms and data structures for automatic graph drawing.

General references

[edit]- Di Battista, Giuseppe; Eades, Peter; Tamassia, Roberto; Tollis, Ioannis G. (1998), Graph Drawing: Algorithms for the Visualization of Graphs, Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0-13-301615-4.

- Herman, Ivan; Melançon, Guy; Marshall, M. Scott (2000), "Graph Visualization and Navigation in Information Visualization: A Survey", IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 6 (1): 24–43, doi:10.1109/2945.841119.

- Jünger, Michael; Mutzel, Petra (2004), Graph Drawing Software, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-00881-1.

Specialized subtopics

[edit]- Anderson, James Andrew; Head, Thomas J. (2006), Automata Theory with Modern Applications, Cambridge University Press, pp. 38–41, ISBN 978-0-521-84887-9.

- Bachmaier, Christian; Brandes, Ulrik; Schreiber, Falk (2014), "Biological Networks", in Tamassia, Roberto (ed.), Handbook of Graph Drawing and Visualization, CRC Press, pp. 621–651.

- Bastert, Oliver; Matuszewski, Christian (2001), "Layered drawings of digraphs", in Kaufmann, Michael; Wagner, Dorothea (eds.), Drawing Graphs: Methods and Models, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2025, Springer-Verlag, pp. 87–120, doi:10.1007/3-540-44969-8_5, ISBN 978-3-540-42062-0.

- Beckman, Brian (1994), Theory of Spectral Graph Layout, Tech. Report MSR-TR-94-04, Microsoft Research, archived from the original on 2016-04-01, retrieved 2011-09-17.

- Brandes, Ulrik; Freeman, Linton C.; Wagner, Dorothea (2014), "Social Networks", in Tamassia, Roberto (ed.), Handbook of Graph Drawing and Visualization, CRC Press, pp. 805–839.

- Di Battista, Giuseppe; Rimondini, Massimo (2014), "Computer Networks", in Tamassia, Roberto (ed.), Handbook of Graph Drawing and Visualization, CRC Press, pp. 763–803.

- Doğrusöz, Uğur; Madden, Brendan; Madden, Patrick (1997), "Circular layout in the Graph Layout toolkit", in North, Stephen (ed.), Symposium on Graph Drawing, GD '96 Berkeley, California, USA, September 18–20, 1996, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 1190, Springer-Verlag, pp. 92–100, doi:10.1007/3-540-62495-3_40, ISBN 978-3-540-62495-0.

- Eiglsperger, Markus; Fekete, Sándor; Klau, Gunnar (2001), "Orthogonal graph drawing", in Kaufmann, Michael; Wagner, Dorothea (eds.), Drawing Graphs, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2025, Springer Berlin / Heidelberg, pp. 121–171, doi:10.1007/3-540-44969-8_6, ISBN 978-3-540-42062-0.

- Freese, Ralph (2004), "Automated lattice drawing", in Eklund, Peter (ed.), Concept Lattices: Second International Conference on Formal Concept Analysis, ICFCA 2004, Sydney, Australia, February 23-26, 2004, Proceedings (PDF), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2961, Springer-Verlag, pp. 589–590, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.69.6245, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-24651-0_12, ISBN 978-3-540-21043-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-14, retrieved 2011-09-17.

- Garg, Ashim; Tamassia, Roberto (1995), "Upward planarity testing", Order, 12 (2): 109–133, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.10.2237, doi:10.1007/BF01108622, MR 1354797, S2CID 14183717.

- Grandjean, Martin (2014), "La connaissance est un réseau", Les Cahiers du Numérique, 10 (3): 37–54, doi:10.3166/lcn.10.3.37-54, archived from the original on 2015-06-27, retrieved 2014-10-15.

- Gutwenger, Carsten; Mutzel, Petra (1998). "Planar Polyline Drawings with Good Angular Resolution". In Sue Whitesides (ed.). Graph Drawing, 6th International Symposium. Springer. pp. 167–182. doi:10.1007/3-540-37623-2_13.

- Holten, Danny; Isenberg, Petra; van Wijk, Jarke J.; Fekete, Jean-Daniel (2011), "An extended evaluation of the readability of tapered, animated, and textured directed-edge representations in node-link graphs", IEEE Pacific Visualization Symposium (PacificVis 2011) (PDF), pp. 195–202, doi:10.1109/PACIFICVIS.2011.5742390, ISBN 978-1-61284-935-5, S2CID 16526781, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-04-11, retrieved 2011-09-29.

- Holten, Danny; van Wijk, Jarke J. (2009), "A user study on visualizing directed edges in graphs", Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '09) (PDF), pp. 2299–2308, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.212.5461, doi:10.1145/1518701.1519054, ISBN 9781605582467, S2CID 9725345, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-06.

- Kant, Goos (1992). "Drawing planar graphs using the lmc-ordering". 33rd Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science. IEEE. pp. 101–110.

- Knuth, Donald E. (2013), "Two thousand years of combinatorics", in Wilson, Robin; Watkins, John J. (eds.), Combinatorics: Ancient and Modern, Oxford University Press, pp. 7–37.

- Koren, Yehuda (2005), "Drawing graphs by eigenvectors: theory and practice", Computers & Mathematics with Applications, 49 (11–12): 1867–1888, doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2004.08.015, MR 2154691.

- Longabaugh, William (2012), "Combing the hairball with BioFabric: a new approach for visualization of large networks", BMC Bioinformatics, 13 275, doi:10.1186/1471-2105-13-275, PMC 3574047, PMID 23102059.

- Madden, Brendan; Madden, Patrick; Powers, Steve; Himsolt, Michael (1996), "Portable graph layout and editing", in Brandenburg, Franz J. (ed.), Graph Drawing: Symposium on Graph Drawing, GD '95, Passau, Germany, September 20–22, 1995, Proceedings, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 1027, Springer-Verlag, pp. 385–395, doi:10.1007/BFb0021822, ISBN 978-3-540-60723-6.

- Misue, K.; Eades, P.; Lai, W.; Sugiyama, K. (1995), "Layout Adjustment and the Mental Map", Journal of Visual Languages & Computing, 6 (2): 183–210, doi:10.1006/jvlc.1995.1010.

- Nachmanson, Lev; Robertson, George; Lee, Bongshin (2008), "Drawing Graphs with GLEE", in Hong, Seok-Hee; Nishizeki, Takao; Quan, Wu (eds.), Graph Drawing, 15th International Symposium, GD 2007, Sydney, Australia, September 24–26, 2007, Revised Papers, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 4875, Springer-Verlag, pp. 389–394, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-77537-9_38, ISBN 978-3-540-77536-2.

- Pach, János; Sharir, Micha (2009), "5.5 Angular resolution and slopes", Combinatorial Geometry and Its Algorithmic Applications: The Alcalá Lectures, Mathematical Surveys and Monographs, vol. 152, American Mathematical Society, pp. 126–127.

- Purchase, H. C.; Cohen, R. F.; James, M. I. (1997), "An experimental study of the basis for graph drawing algorithms", Journal of Experimental Algorithmics, 2, Article 4, doi:10.1145/264216.264222, S2CID 22076200.

- Reingold, Edward M.; Tilford, John S. (1981). "Tidier drawings of trees". IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 2 (2): 223–228. doi:10.1109/TSE.1981.234519.

- Saaty, Thomas L. (1964), "The minimum number of intersections in complete graphs", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 52 (3): 688–690, Bibcode:1964PNAS...52..688S, doi:10.1073/pnas.52.3.688, PMC 300329, PMID 16591215.

- Scott, John (2000), "Sociograms and Graph Theory", Social network analysis: a handbook (2nd ed.), Sage, pp. 64–69, ISBN 978-0-7619-6339-4.

- Sugiyama, Kozo; Tagawa, Shôjirô; Toda, Mitsuhiko (1981), "Methods for visual understanding of hierarchical system structures", IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, SMC-11 (2): 109–125, doi:10.1109/TSMC.1981.4308636, MR 0611436, S2CID 8367756.

- Sugiyama, Kozo; Misue, Kazuo (1995). "Graph drawing by the magnetic spring model". Journal of Visual Languages & Computing. 6 (3): 217–231. doi:10.1006/jvlc.1995.1013.

- Tamassia, Roberto (1987). "On Embedding a Graph in the Grid with the Minimum Number of Bends". SIAM Journal on Computing. 16 (3): 421–444. doi:10.1137/0216030.

- Tantau, Till (2013), "Graph Drawing in TikZ", Journal of Graph Algorithms and Applications, 17 (4): 495–513, doi:10.7155/jgaa.00301 (inactive July 15, 2025)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link). - Zapponi, Leonardo (August 2003), "What is a Dessin d'Enfant" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 50: 788–789, archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-10-03, retrieved 2021-04-28.

Further reading

[edit]- Di Battista, Giuseppe; Eades, Peter; Tamassia, Roberto; Tollis, Ioannis G. (1994), "Algorithms for Drawing Graphs: an Annotated Bibliography", Computational Geometry: Theory and Applications, 4 (5): 235–282, doi:10.1016/0925-7721(94)00014-x.

- Kaufmann, Michael; Wagner, Dorothea, eds. (2001), Drawing Graphs: Methods and Models, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 2025, Springer-Verlag, doi:10.1007/3-540-44969-8, ISBN 978-3-540-42062-0, S2CID 1808286.

- Tamassia, Roberto, ed. (2014), Handbook of Graph Drawing and Visualization, CRC Press, archived from the original on 2013-08-15, retrieved 2013-08-28.

External links

[edit]- GraphX library for .NET Archived 2018-01-26 at the Wayback Machine: open-source WPF library for graph calculation and visualization. Supports many layout and edge routing algorithms.

- Graph drawing e-print archive: including information on papers from all Graph Drawing symposia.

Graph drawing

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Principles

Graph drawing is the algorithmic process of visualizing an abstract graph by mapping its vertices to points in the Euclidean plane (or higher-dimensional space) and representing its edges as curves or line segments connecting those points, with the goal of producing a clear and informative layout.[4] This embedding distinguishes between the abstract combinatorial structure of the graph and its geometric realization, where the positions of vertices and the paths of edges determine the visual properties such as crossings and readability.[5] At its core, graph drawing operates on graphs defined in graph theory, where an undirected graph consists of a set of vertices and a set of edges connecting pairs of vertices, without self-loops or multiple edges between the same pair in simple graphs; multigraphs allow multiple edges, while directed graphs incorporate edge orientations.[6] Common drawing styles include straight-line drawings, where edges are line segments; polyline drawings, where edges are polygonal chains; and orthogonal drawings, where edges consist of horizontal and vertical segments.[4] A fundamental objective in many embeddings, particularly planar ones, is to minimize the total edge length, formulated as , where denotes the position of vertex .[7] The scope of graph drawing encompasses both static drawings for fixed graphs and dynamic drawings that adapt to changes in the graph structure over time, often requiring smooth animations between layouts; it also extends to 2D and 3D spaces, though 2D remains the primary focus for readability.[8]Historical Development

The theoretical foundations of graph drawing trace back to early 20th-century results on planar graphs. In 1936, Klaus Wagner proved that every planar graph admits a straight-line embedding without crossings, establishing a key property for geometric representations. Independently, in 1948, István Fáry extended this by showing that any simple planar graph can be drawn with straight-line edges, providing the first rigorous guarantee for crossing-free straight-line drawings. These results laid the groundwork for algorithmic approaches but were primarily theoretical, predating computational applications.[9][10] The practical development of graph drawing algorithms began in the 1960s with the advent of computer graphics. A seminal contribution was W.T. Tutte's 1963 method for embedding 3-connected planar graphs using barycentric coordinates, which produced straight-line drawings by solving a system of linear equations based on spring-like forces. This marked one of the earliest force-directed techniques, bridging theory and computation. The 1980s saw further advancements: Kozo Sugiyama and colleagues introduced the layered drawing framework in 1981 for hierarchical directed graphs, emphasizing topological ordering and edge bundling to enhance readability. Peter Eades followed in 1984 with a heuristic spring-embedder model for general undirected graphs, simulating physical forces to minimize edge crossings and optimize symmetry. These methods established core paradigms for automated visualization.[11][12][13] The 1990s formalized the field through dedicated research and resources. The first International Symposium on Graph Drawing was held in 1992 near Rome, Italy, fostering a dedicated community and annual proceedings that advanced algorithmic and aesthetic criteria. A landmark publication, the 1999 book Graph Drawing: Algorithms for the Visualization of Graphs by Giuseppe Di Battista, Peter Eades, Roberto Tamassia, and Ioannis G. Tollis, synthesized foundational techniques and became a standard reference for researchers. Entering the 2000s, the focus shifted toward scalability for large networks, with force-directed methods adapted to handle graphs exceeding 100,000 vertices through approximations and parallelization; extensions to 3D drawings also gained traction for immersive visualizations. Software tools like Graphviz (1991 onward), Cytoscape (2003), and Gephi (2008) integrated these algorithms, enabling practical deployment in domains such as biology and social sciences.[1] Post-2010 developments emphasized big data applications, driven by the explosion of network data in social media, bioinformatics, and web analytics. The Graph Drawing symposia reflected this evolution, with the 31st in Palermo, Italy (2023), the 32nd in Vienna, Austria (2024), and the 33rd in Norrköping, Sweden (2025), increasingly featuring tracks on dynamic, massive-scale, and interactive visualizations. This period saw innovations in stress-minimizing layouts and hybrid methods to address scalability challenges, underscoring graph drawing's role in interpreting complex real-world networks.[14][15][16][1]Visual Conventions

Node and Edge Representations

In graph drawing, nodes representing vertices are commonly depicted as simple geometric shapes such as circles, ellipses, or points to facilitate clear identification and positioning in the plane.[17] These shapes are chosen for their neutrality and minimal visual clutter, allowing focus on relational structures rather than ornate designs.[18] Node size can encode attributes like vertex degree, with larger diameters indicating higher connectivity, while colors differentiate node types or clusters, enhancing interpretability in complex graphs. Labels, typically textual identifiers, are placed adjacent to nodes, often outside or within the shape if space permits, to avoid obscuring connections.[17] Edges, representing connections between vertices, are visualized as lines or curves linking node centers to maintain relational clarity. Straight lines are preferred for their simplicity and directness in non-orthogonal layouts, promoting ease of tracing relationships.[18] For orthogonal drawings, polylines with right-angle bends are used to align with grid structures, reducing angular ambiguity.[17] Curved edges, such as splines or arcs, appear in aesthetic-focused layouts to minimize visual crossings and improve flow perception. Edge thickness varies to denote weights, with thicker lines signaling stronger or more significant connections, while arrows at endpoints indicate directionality in directed graphs.[19] Standard conventions adapt these representations to domain-specific needs for consistency and readability. In Unified Modeling Language (UML) for software graphs, nodes for classes are rendered as rectangles containing compartments for attributes and methods, while edges use solid lines for associations and dashed lines for dependencies. Network diagrams often employ dashed or dotted lines for virtual or logical links to distinguish them from solid lines representing physical connections.[20] A core convention across these visualizations is the avoidance of overlapping nodes or edges, ensuring distinct separation to prevent misinterpretation of adjacency or hierarchy.[21]Standard Notations and Symbols

In graph drawing, standard notations for graphs often begin with abstract representations such as adjacency matrices, where rows and columns correspond to vertices and entries indicate the presence or absence of edges between them. However, when transitioning to visual drawings, vertices are typically denoted by alphanumeric labels, such as single letters (e.g., v_1, u) or identifiers representing entities like nodes in a network.[19] Edge notations in drawings include labels for attributes like weights or costs, often placed along the line segments to convey quantitative information without altering the geometric layout. Symbols for edges distinguish between undirected and directed graphs through simple visual cues: undirected edges are represented as plain straight or curved lines connecting two vertices, implying bidirectional connectivity, while directed edges incorporate arrowheads at one endpoint to indicate the orientation of the relationship.[19] These conventions ensure clarity in interpreting flow or association, with arrowheads typically styled as filled triangles or chevrons for emphasis. Clusters or groups of vertices, such as subgraphs or communities, are commonly enclosed by bounding boxes—rectangular outlines—or differentiated via distinct colors to highlight modular structures without overlapping individual elements.[22] Domain-specific adaptations extend these notations for interpretability in specialized fields. In biological network visualizations, nodes representing genes or proteins may use icons like ovals for simple entities or cut-corner rectangles (octagons) for complexes, following the Systems Biology Graphical Notation (SBGN) to standardize process descriptions and entity relationships.[23] For social networks, vertices often incorporate user avatars or profile icons instead of generic labels, allowing quick recognition of individuals or groups while maintaining edge symbols for interactions like friendships or follows.[19] Flowcharts, a subset of graph drawings, adhere to ISO 5807 standards, employing symbols such as rectangles for processes, diamonds for decisions, and arrows for directional flow between elements.[24] Tools like LaTeX with the TikZ package facilitate precise symbolic rendering in academic and technical drawings, enabling customizable vertex shapes, edge arrows, and labels through declarative code that avoids manual positioning errors. In multi-edge graphs, where multiple connections exist between the same pair of vertices, ambiguity is mitigated by parallel edge routing, distinct line styles (e.g., dashed vs. solid), or explicit numeric labels on each edge to differentiate instances.[19]Quality Evaluation

Aesthetic Criteria

Aesthetic criteria in graph drawing refer to a set of principles aimed at enhancing the visual appeal and readability of graph layouts, often balancing subjective human preferences with objective geometric properties. These criteria guide the design of algorithms to produce drawings that facilitate comprehension of graph structure, such as relationships between nodes and edges. While some criteria are qualitative, others can be quantified through metrics, serving as optimization targets in layout methods. Empirical research has validated that adhering to these criteria improves user task performance, particularly in domains like software visualization and network analysis.[25] Key aesthetic criteria include uniform edge lengths, where edges are ideally of similar length to avoid visual imbalance; minimal bends, preferring straight or low-curvature edges for clarity; and symmetry, which exploits graph symmetries to create balanced, intuitive layouts. Aspect ratio balance seeks a drawing whose bounding box has a width-to-height ratio close to 1, suitable for standard displays without excessive whitespace. Readability is further enhanced by node-edge separation, ensuring sufficient distance between non-adjacent vertices and edges to prevent overlaps. These elements collectively contribute to a drawing's overall coherence, though they often involve trade-offs, such as prioritizing uniform edge lengths over compactness.[25] A seminal framework for these criteria was proposed by Helen C. Purchase, identifying seven common aesthetics derived from graph drawing literature and validated through user studies. These are:- Minimize bends: Reduce the total number of direction changes in polyline edges to promote smoothness.

- Node distribution: Evenly spread nodes within the bounding box to avoid clustering and improve spatial uniformity.

- Edge variation: Maintain uniform edge lengths to enhance perceptual consistency.

- Direction of flow: Align edges in a consistent direction, often top-to-bottom or left-to-right, to suggest hierarchy.

- Orthogonality: Align edges and nodes to a grid, minimizing diagonal lines for a structured appearance.

- Edge lengths: Keep edges short but not excessively so, balancing density and visibility.

- Symmetry: Display symmetric substructures where possible, leveraging human bias toward balanced forms.[25]

Planarity and Crossing Metrics

In graph drawing, planarity refers to the property of a graph that allows it to be embedded in the plane without any edge crossings, meaning vertices are represented as points and edges as non-intersecting curves connecting them.[27] A graph possessing this property is called planar, and such an embedding preserves the graph's combinatorial structure while ensuring topological embeddability.[27] Kuratowski's theorem provides a precise characterization of non-planar graphs: a finite undirected graph is planar if and only if it contains no subgraph that is a subdivision of the complete graph or the complete bipartite graph .[27] These forbidden subgraphs serve as the minimal obstructions to planarity, enabling algorithmic tests for embeddability by searching for such subdivisions.[27] For non-planar graphs, crossing metrics quantify the extent of unavoidable edge intersections in drawings. The crossing number of a graph is defined as the minimum number of edge crossings over all possible drawings in the plane, where a crossing occurs at the intersection point of two edges that do not share a vertex.[28] This metric counts the total number of such intersection points, assuming a simple drawing where edges intersect transversely and at most once per pair; an edge crossing pair refers to a pair of non-adjacent edges that intersect in the drawing.[28] Computing exactly is NP-complete, even for restricted classes of graphs.[29] Upper bounds on provide insight into the scale of crossings; for a graph with vertices, a trivial bound is , but improved estimates show in the worst case, as realized by complete graphs where .[28] Fáry's theorem establishes that every planar graph admits a straight-line drawing without crossings, where edges are represented as line segments, bridging combinatorial planarity with geometric realizations.[10] In dense graphs, where edge density approaches , crossing metrics often normalize the total crossings to assess impact; for instance, the average number of crossings per edge, computed as , highlights how intersections distribute across edges, with values exceeding 1 indicating significant clutter in optimal drawings.[30] Crossing density, defined as , further scales this for dense cases, approaching constants like 1/64 for complete graphs to quantify topological complexity.[31]Core Layout Techniques

Force-Directed Methods

Force-directed methods are a class of graph drawing algorithms inspired by physical systems, where nodes are modeled as particles that repel each other, and edges act as springs that attract connected nodes toward an equilibrium state.[32] This simulation seeks a layout where repulsive forces between all pairs of nodes balance the attractive forces along edges, resulting in a configuration that minimizes overall energy and promotes even distribution of nodes.[32] The approach is particularly effective for undirected graphs, producing organic, aesthetically pleasing layouts without requiring specific graph properties like planarity.[32] One of the earliest and most influential algorithms is the Kamada-Kawai method, which minimizes an energy function defined aswhere and are the positions of nodes and , is the ideal distance based on graph-theoretic shortest paths (scaled by a constant ), and is a stiffness coefficient inversely proportional to the square of the shortest path distance.[33][32] This formulation treats the layout as an optimization problem, aiming to make geometric distances approximate graph distances.[33] The Fruchterman-Reingold algorithm builds on this spring model with explicit force definitions: attractive forces pulling connected nodes together, and repulsive forces pushing all nodes apart, where is the distance between nodes and is a scaling factor derived from the graph's area and number of vertices ().[34][32] Iterations apply these forces as vectors to update node positions, with a cooling "temperature" schedule that limits displacement in later steps to prevent oscillations and ensure convergence to a stable layout.[34] Convergence in force-directed methods is achieved through iterative numerical techniques, such as gradient descent variants like the Newton-Raphson method in Kamada-Kawai, which solves the partial derivatives of the energy function to adjust positions toward local minima.[32] Alternatively, simulated annealing can be incorporated, as in later extensions, to escape local minima by allowing probabilistic acceptance of worse configurations during a cooling process, improving global optimization for criteria like edge crossing reduction.[32] These methods are best suited for small to medium undirected graphs with fewer than 1000 vertices, where computational costs remain manageable and layouts avoid clustering artifacts common in larger instances.[32] For graphs exceeding a few hundred nodes, they often require enhancements to handle quadratic time complexity in repulsive force calculations.[32] A notable variant is the concentric or radial force-directed layout, which constrains nodes to concentric circles centered on a focal node or point, combining repulsive and attractive forces with angular adjustments to emphasize hierarchy or focus+context views in clustered graphs.[35] This adaptation maintains the core physics simulation while enforcing radial symmetry for improved readability in networks with natural centers.[35]

Layered and Hierarchical Layouts

Layered and hierarchical layouts organize the vertices of a directed graph into distinct levels or layers, typically arranged vertically, to reveal the underlying topological structure and flow of information. This approach is particularly suited for directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), where edges point from upper layers to lower ones, minimizing edge bends and enhancing readability. The seminal Sugiyama framework, introduced in 1981, provides a multi-phase algorithm for generating such drawings by systematically assigning layers, ordering vertices within layers, positioning nodes, and routing edges.[12] To accommodate graphs with cycles, the framework first removes cycles by computing a feedback arc set, which identifies and reverses a minimal set of edges to render the graph acyclic; heuristics such as depth-first search orderings or greedy methods are commonly employed for this step. Once acyclic, the ranking phase assigns each vertex to a layer based on its topological position. A standard method is the longest path ranking, which places a vertex in a layer equal to the length of the longest directed path from a source vertex to it, ensuring the drawing has minimal height while distributing vertices across layers.[36][12] The crossing reduction phase then orders vertices within each layer to minimize edge intersections, primarily between consecutive layers. This is achieved iteratively using heuristics like the barycenter method, where each vertex's position is determined by the average (barycenter) of its neighbors' positions in adjacent layers, or the median heuristic, which uses the median instead to reduce sensitivity to outliers. These one-sided optimizations sweep upward and downward through the layers until convergence, significantly lowering crossings in practice.[36][12] Following ordering, coordinate assignment positions vertices horizontally within layers, often aligning chains of dummy vertices (introduced to subdivide long edges spanning multiple layers) using techniques like median placement to minimize edge bends. Edge routing then connects vertices with straight lines or polylines, ensuring at most two bends per original edge. The resulting layouts are widely used in visualizing flowcharts and Unified Modeling Language (UML) diagrams, where hierarchical relationships must be clearly conveyed.[36][12] The effectiveness of the ordering step hinges on minimizing the crossing number between consecutive layers and , defined for layer orderings and as the total number of edge pairs that cross: where denotes layer , and the sum counts inversions in the relative ordering of edge endpoints. This NP-hard problem is approximated by the barycenter and median heuristics, which yield substantial reductions in crossings for real-world graphs.[36][12]Orthogonal and Grid-Based Drawings

Orthogonal drawings of graphs position vertices at points in the plane and represent edges as polylines consisting exclusively of horizontal and vertical segments, ensuring that no two edges cross except possibly at shared endpoints.[37] This style is particularly suited for applications requiring right-angle routing, such as circuit schematics, where straight-line edges would be impractical. A key objective in orthogonal drawings is bend minimization, where a bend on an edge is defined as a point where the direction changes from horizontal to vertical or vice versa; the total number of bends across all edges, denoted as with being the number of direction changes on edge , measures the complexity and readability of the drawing.[37] Seminal work by Tamassia introduced an algorithm for computing an orthogonal drawing of a planar graph with a fixed combinatorial embedding that minimizes the total number of bends using a minimum-cost flow network, achieving time complexity for graphs with vertices under certain conditions.[37] However, finding an optimal orthogonal drawing that minimizes bends over all possible planar embeddings of the graph is NP-hard, as established by reductions showing that even deciding the existence of a bend-free (rectilinear) drawing is NP-complete for planar graphs of maximum degree four.[38] To address this, practical algorithms often fix a planar embedding first and then optimize the shape within it, balancing computational feasibility with aesthetic quality. Visibility representations provide a foundational technique for constructing orthogonal drawings, where vertices are mapped to horizontal line segments and edges to vertical visibilities between them, ensuring no obstructions between adjacent segments. Tamassia and Tollis developed a unified framework for such representations of planar graphs, enabling linear-time construction for st-connected graphs and extending to general cases via decomposition into series-parallel components.[39] This approach facilitates polyline routing by transforming visibility graphs into orthogonal layouts with controlled bend counts, often integrating with flow-based methods for further refinement. Grid-based orthogonal drawings impose the additional constraint that all vertices and bend points lie on integer coordinates of a grid, promoting compactness and alignment in automated layouts. Compaction techniques then minimize the drawing's area by sliding components horizontally and vertically while preserving the orthogonal representation and non-crossing properties, formulated as a simultaneous optimization of x- and y-coordinates subject to inequality constraints on positions. Klau et al. presented an integer linear programming model for optimal two-dimensional compaction, solvable in polynomial time for fixed embeddings and yielding area reductions up to 50% in benchmarks compared to naive placements.[40] These methods are widely applied in VLSI layout design, where orthogonal grid drawings model routing channels and minimize wire lengths in integrated circuits.[41]Advanced Algorithms

Planar Embedding Algorithms

Planar embedding algorithms focus on determining whether a graph is planar and, if so, constructing a crossing-free embedding in the plane, either combinatorially (specifying the cyclic order of edges around vertices) or geometrically (assigning coordinates to vertices). These algorithms are foundational for graph drawing, as they guarantee zero edge crossings for planar graphs, enabling further aesthetic refinements like straight-line representations. Seminal methods combine planarity testing with embedding construction, often leveraging depth-first search (DFS) trees to efficiently handle the topological constraints of planarity.[42] A cornerstone of planarity testing is the Hopcroft-Tarjan algorithm from 1974, which determines in linear time whether an arbitrary undirected graph with n vertices admits a planar embedding. The approach builds a DFS spanning tree and computes lowpoint values for each vertex, defined as the smallest discovery time reachable from the subtree rooted at that vertex, including via back edges. By comparing lowpoint values to discovery times, the algorithm identifies articulation points and interleaves paths to construct a potential embedding; if no contradictions arise in the ordering of back edges relative to the tree, the graph is planar, and a combinatorial embedding is output. This O(n) time complexity arises from a single DFS pass augmented with stack-based path merging, making it highly efficient for large graphs.[42] For constructing combinatorial embeddings, the left-right planarity test provides an elegant DFS-based characterization, originally formulated by de Fraysseix and Rosenstiehl in 1982. In this method, a DFS tree is constructed, and back edges are classified as "left" or "right" relative to the tree edges based on their angular position in a hypothetical embedding, ensuring that left edges do not cross right edges in the fundamental cycles they form. The test verifies planarity by checking that the left and right sets induce non-intersecting orderings around each vertex, allowing the cyclic order of edges to be built incrementally without crossings. This criterion enables linear-time embedding for general planar graphs and has influenced practical implementations due to its simplicity and avoidance of complex data structures.[43] Straight-line planar embeddings, where edges are drawn as straight segments, can be derived from combinatorial embeddings using methods like the shift technique of de Fraysseix, Pach, and Pollack from 1990. Starting from a combinatorial embedding of a maximal planar graph (triangulation), the algorithm places the outer face vertices on a convex hull and incrementally adds internal vertices by shifting coordinates to maintain planarity and convexity. Specifically, for a vertex v added inside a face, its position is computed as the average of its neighbors' positions plus a small shift vector to avoid collinearities, ensuring all faces remain strictly convex. This produces a straight-line drawing on an O(n) × (2n − 4) grid in linear time, with vertices at integer coordinates.[44] Central to such straight-line constructions is the canonical ordering, a vertex sequence σ = (v_1, v_2, ..., v_n) for 3-connected planar graphs that facilitates incremental drawing while preserving outer-face convexity. The ordering begins with two adjacent vertices v_1 and v_2 on the outer face, and for each subsequent v_i (3 ≤ i ≤ n), the neighbors of v_i in the subgraph induced by {v_1, ..., v_{i-1}} form a contiguous segment on the outer face of that subgraph, with v_i adjacent to at least two earlier vertices. This property ensures that adding v_i splits a face without introducing crossings, and the final drawing has the outer face as a convex polygon. Canonical orderings can be computed in O(n) time via DFS or SPQR-tree decompositions and are particularly efficient for 3-connected graphs, where Whitney's uniqueness theorem implies a single embedding class, simplifying the process.[44] For directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), planar embedding algorithms extend to upward drawings, where all edges point upward (increasing y-coordinates). General upward planarity testing is NP-hard (Garg and Tamassia, 1995).[45] For certain classes, such as single-source DAGs (biconnected with a specified root), it can be tested in linear time by reducing to planarity testing on an auxiliary undirected graph that encodes direction constraints (Bertolazzi et al., 1998).[46] If upward planar, a straight-line upward embedding can be constructed using layered approaches or barycentric methods, ensuring monotonic edge directions and no crossings. These methods handle 3-connected cases efficiently by leveraging canonical-like orderings adapted for directions.Crossing Minimization Techniques

Crossing minimization in graph drawing seeks to arrange vertices and edges to reduce the number of edge intersections, particularly in non-planar graphs where crossings are unavoidable. In layered graph drawings, where vertices are partitioned into parallel layers and edges connect consecutive layers, the problem focuses on ordering vertices within each layer to minimize inter-layer crossings. The objective is to minimize the total number of crossings, defined as the sum over all pairs of edges that intersect when drawn as straight lines between layers.[28] The two-layer crossing minimization problem, where vertices are fixed in two parallel lines and only the ordering in one or both layers can be permuted, is NP-hard, even in the one-sided case where one layer's ordering is fixed.[47] This complexity arises from reductions to ordering problems like feedback arc set. For multi-layer drawings, the problem is addressed through iterative sweeps: start with an initial ordering, then repeatedly apply two-layer minimization between consecutive layers until convergence, as in the Sugiyama framework.[36] This layer-by-layer approximation assumes that minimizing local crossings reduces the global total, though it may not yield optimality. Key heuristics for two-layer crossing minimization include the barycenter method and the median method. The barycenter heuristic positions each vertex in the second layer at the average (barycenter) position of its neighbors in the first layer, iteratively refining the ordering to reduce crossings; it originates from early hierarchical drawing algorithms and provides a linear-time approximation with known bounds up to four times the optimum in worst cases. The median heuristic, which places each vertex at the median position of its neighbors, offers better performance on sparse graphs and an approximation ratio of 3 for the one-sided case, making it suitable for initial orderings in multi-layer sweeps. For global optimization in multi-layer settings, genetic algorithms and evolutionary methods explore the search space more broadly than local heuristics. These represent layer orderings as chromosomes, using crossover and mutation to evolve solutions that minimize total crossings, often hybridized with barycenter or sifting for local improvements; a seminal hybridized genetic algorithm demonstrated superior results on dense digraphs compared to iterative heuristics alone.[48] Recent evolutionary computation hybrids, such as simple evolutionary algorithms with swap mutations, achieve near-optimal crossings on planarizable instances and outperform traditional heuristics on benchmark suites, with runtime analyses confirming polynomial expected time for small perturbations.[49] The total crossings in a layered drawing with orderings for layer can be approximated by summing pairwise inter-layer crossings: where the sum counts inverting edge pairs between consecutive layers.[50] Exact methods, such as integer linear programming formulations, solve the problem optimally for small instances (up to 50 vertices) by modeling orderings as variables and crossings as quadratic constraints linearized via big-M techniques; these provide benchmarks for heuristics but scale poorly due to NP-hardness.Parameterized and Approximation Algorithms

In graph drawing, parameterized algorithms address the computational challenges of NP-hard problems by exploiting small parameters, such as the solution size or structural graph properties, to achieve fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) running times. A prominent example is the crossing number problem, which seeks the minimum number of edge crossings in a drawing of a graph with vertices. This problem is FPT when parameterized by the solution size , the conjectured minimum crossing number; specifically, there exists an algorithm running in time for some computable function , deciding whether the crossing number is at most and constructing such a drawing if it exists.[51] This result relies on expressing the problem in monadic second-order logic and applying Courcelle's theorem on graphs of bounded local treewidth in the drawing. Subsequent improvements have refined the dependence on to linear time , while maintaining the quadratic bound in early formulations like . Recent unified frameworks extend these FPT techniques to variants of the crossing number, including bundled, edge, and color-constrained crossings on surfaces of bounded genus. For instance, a 2024 framework provides quadratic FPT algorithms for determining the minimum crossings in topological drawings under various constraints, such as -planar or fan-crossing-free configurations, parameterized jointly by the number of crossings and genus .[52] Similarly, for beyond-planar graphs, deciding if a graph admits a drawing with at most crossings while avoiding specific forbidden crossing patterns (e.g., in -planar or quasi-planar classes) is FPT in for fixed pattern families. These advances, presented at the 2024 Graph Drawing Symposium, highlight how parameterization enables exact solutions for "almost planar" graphs with few crossings, improving scalability over brute-force methods. Treewidth serves as another key parameter for graph drawing, bounding the complexity of decompositions to facilitate dynamic programming approaches. Graphs of bounded treewidth admit efficient algorithms for planar embeddings and low-crossing drawings; for example, computing an optimal planar drawing (zero crossings) is solvable in time where is the treewidth, via standard MSO encodings.[53] Drawn tree decompositions further integrate drawing constraints directly into the decomposition process, enabling FPT algorithms for visualizing graphs with bounded treewidth while optimizing aesthetics like edge lengths or crossings.[54] Approximation algorithms complement parameterized methods by providing near-optimal drawings in polynomial time, particularly for intractable objectives like minimizing crossings or area. While the general crossing number admits no polynomial-time approximation scheme (PTAS) unless NP problems are solvable in subexponential time, recent results yield subpolynomial approximations for restricted cases; for low-degree graphs (), a randomized -approximation runs in polynomial time.[55][56] For dense graphs, deterministic algorithms approximate the crossing number up to an additive error in time, aiding practical visualization of large networks. Ongoing research at institutions like TU Wien emphasizes parameterized techniques for visualization challenges, including human-in-the-loop interactions and right-angle crossing (RAC) drawings. For RAC drawings, where adjacent edges cross at most once at right angles, computing a -bend RAC drawing is FPT in , with algorithms running in time via kernelization to bounded treewidth instances.[57] These developments, spanning 2023–2025, bridge theoretical parameterized complexity with practical graph drawing tools, focusing on parameters like bend count or treewidth to handle large-scale visualizations efficiently.Applications

Network and Software Visualization

Graph drawing plays a crucial role in visualizing computer network topologies, where nodes represent entities such as routers or switches and edges depict connections like fiber optic links or wireless transmissions. In large-scale networks, such as the internet backbone, radial layouts are particularly effective for revealing hierarchical structures, positioning central hubs at the core and radiating outward to peripheral nodes to emphasize connectivity patterns and fault propagation. For instance, the PLANET algorithm employs a parent-centric radial approach to distribute nodes evenly around parent nodes using angle assignment rules, minimizing edge crossings and ensuring uniform edge lengths, which is well-suited for exploring router hierarchies in networks with high diameters. This method achieves linear time complexity O(N), enabling efficient rendering of complex topologies while highlighting influential nodes like core routers.[58] A notable application in network debugging occurred at AT&T in the late 1990s, where the SWIFT-3D system was developed to analyze massive telecommunication datasets, including graphs of call volumes and service coverage. Engineers used interactive 3D node-link diagrams to trace anomalies, such as unexplained spikes in unanswered calls, revealing congestion tied to external events like radio contests in specific regions. SWIFT-3D integrated variable-resolution maps with pixel-oriented overviews and drag-and-drop queries, facilitating drill-down from global network views to local edge details for rapid fault isolation. Orthogonal edge drawings, featuring horizontal and vertical segments, are commonly employed in such diagrams, including those for Cisco networks, to enhance readability by aligning connections with grid-like topologies and reducing visual ambiguity in device interconnections.[59][60] However, scalability poses significant challenges for graphs exceeding 100,000 nodes, as traditional force-directed algorithms suffer from computational bottlenecks due to quadratic edge force calculations, often failing to converge or rendering in hours on standard hardware. Visual clutter arises from node overlaps and edge tangles in dense networks, limiting effective analysis without GPU acceleration or sampling techniques. Tools like Cosmograph address this by leveraging WebGL for GPU-based force layouts, successfully visualizing up to one million nodes—such as a 475,448-node dataset with over one million edges—in interactive browser environments, though performance degrades with irregular densities.[61][62] In software visualization, graph drawing supports the representation of structural relationships, such as UML class diagrams and call graphs, aiding developers in comprehending dependencies and control flows. For UML class diagrams, techniques like the GoVisual approach preprocess graphs to ensure uniform upward directions and planarity, followed by orthogonal layouts that minimize bends and crossings while merging multiple inheritance edges for clarity. This results in diagrams with zero crossings in complex hierarchies, outperforming earlier methods in readability for object-oriented designs. Call graph visualizations, which model method invocations as directed edges, employ interactive layouts encoding causality and reachability; the REACHER tool, for example, uses static analysis and feasible path queries to navigate large codebases, improving debugging success rates by 5.6 times and reducing task times significantly in empirical studies.[63][64] Graphviz exemplifies practical application in software dependency visualization, generating layouts from DOT descriptions to depict module interdependencies in large programs. In maintenance scenarios, it illustrates relationships among code modifications—such as nodes for file changes pointing to impacted components—enabling testers to isolate subsets for verification and cut costs by identifying critical dependencies. Layered methods, briefly, can enhance these views for directed dependencies, though Graphviz's spring-based neato layout often suffices for undirected maintenance graphs.[65]Biological and Social Graph Drawings

Graph drawing plays a crucial role in visualizing biological networks, such as protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, where nodes represent proteins and edges denote physical or functional interactions derived from high-throughput experiments like yeast-two-hybrid assays. Force-directed algorithms are particularly effective for these networks, as they simulate physical forces to position densely connected nodes closer together, thereby revealing functional clusters such as signaling pathways or protein complexes. Node attributes, including colors and shapes, are often used to encode biological properties, like gene ontology annotations for molecular function or subcellular localization, enhancing interpretability for researchers studying cellular processes. Metabolic pathways, another key biological application, are drawn to illustrate biochemical reactions and regulatory dependencies, with force-directed layouts helping to compact hierarchical flows while preserving directional edges from substrates to products. The open-source platform Cytoscape, first released in 2003, has become a standard tool for these visualizations, enabling the integration of omics data (e.g., expression levels) with network topology to highlight dynamic changes in pathway activity. However, real-world biological data often introduces noise from experimental variability or incomplete interactions, complicating accurate cluster detection and requiring robust preprocessing steps like edge weighting based on confidence scores.[66] In the 2020s, visualizing large-scale biological networks—such as those from single-cell RNA sequencing or multi-omics integration—presents scalability challenges, with datasets exceeding millions of nodes overwhelming traditional force-directed methods due to computational demands and visual clutter. Advances in sampling techniques and hybrid layouts address these issues, allowing interactive exploration of big data networks while maintaining biological insights, though full automation remains limited by data heterogeneity.[67] For social graphs, drawing techniques adapt to friendship networks and collaboration graphs, where force-directed spring layouts emphasize community structures by attracting connected nodes and repelling others, uncovering social clusters like interest groups or professional circles. In examples from platforms like Facebook, these layouts visualize ego networks of users' connections, with edge thickness representing interaction frequency to illustrate tie strengths in real-time social dynamics. Gephi, an open-source tool developed in the late 2000s, facilitates such drawings through interactive filtering and dynamic attributes, supporting analyses of evolving networks from sources like Twitter or co-authorship databases. Noise in social data, such as self-reported ties or platform biases, poses challenges akin to biological networks, often mitigated by statistical edge validation to ensure reliable community detection.[68]Emerging Uses in AI and Machine Learning

Graph drawing techniques are increasingly integrated with artificial intelligence and machine learning to address challenges in visualizing large-scale, complex graphs, particularly where traditional algorithms falter in scalability and adaptability. Machine learning enhancements, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), have been employed to predict and generate graph layouts by learning structural patterns from data. For instance, GNN-based models can accelerate network layout generation, achieving up to 100 times faster computation compared to classical force-directed methods while maintaining comparable aesthetic quality on datasets like social networks and biological graphs.[69] These approaches treat graph drawing as a supervised learning task, where node positions are predicted based on adjacency and feature embeddings, enabling dynamic adjustments for interactive visualizations.[70] Diffusion models represent another advancement, offering probabilistic generation of node placements that respect graph structures. The FrameDiff model, an SE(3)-equivariant diffusion approach, generates protein backbone structures—modeled as graphs—by iteratively denoising rigid frames, outperforming prior methods in producing novel, functional conformations with a success rate exceeding 50% on unseen protein families from the Protein Data Bank.[71] This technique extends to general graph drawing by sampling layouts that minimize crossings and optimize spacing through learned noise reversal, particularly useful for hierarchical or molecular graphs where exact solutions are intractable.[72] Large language models (LLMs) are being leveraged for interpreting graph drawings through prompted visual analysis, enhancing human-AI collaboration in graph comprehension. An empirical study demonstrated that LLMs, such as GPT-4, achieve up to 85% accuracy in tasks like identifying graph properties (e.g., connectivity or centrality) when provided with textual descriptions of drawings generated via force-directed or layered layouts, with performance improving via iterative prompting on aesthetic variations.[73] This application bridges graph drawing with natural language processing, allowing LLMs to generate insights or refine layouts based on user queries about visualized data. In dimensionality reduction, techniques like t-SNE and UMAP are augmented with graph theory to produce embeddings that preserve topological properties for visualization. A unifying framework integrates these methods with graph drawing principles, such as planarity and crossing numbers, to validate and refine low-dimensional projections; for example, it uses neighborhood graphs to quantify distortion in embeddings of high-dimensional datasets.[74] This hybrid approach ensures that reduced embeddings not only cluster similar nodes but also maintain drawable graph structures suitable for downstream analysis. Evolutionary computation has emerged as a hybrid AI method for optimizing layered graph drawings, particularly in minimizing edge crossings. A 2024 analysis showed that evolutionary algorithms, using mutation operators on vertex orderings, achieve polynomial-time approximations for one-sided crossing minimization in layered layouts, with runtime guarantees such as Θ(n²) expected iterations for certain operators like swaps, demonstrating strong performance on instances that can be drawn crossing-free.[75] Recent Graph Drawing symposia from 2023 to 2025 have highlighted such integrations, including sessions on geometric machine learning for layout generation and parameterized algorithms tailored to AI-driven visualization challenges.[76]Implementation Tools

Open-Source Libraries

Open-source libraries for graph drawing provide extensible frameworks that enable developers, researchers, and data scientists to implement, customize, and integrate drawing algorithms into applications without proprietary constraints. These tools often support core techniques such as force-directed layouts and planar embeddings, while fostering community-driven enhancements through platforms like GitHub. Key examples include longstanding projects like Graphviz and more recent integrations such as PyGraphviz extensions, which have seen updates in the 2020s to improve compatibility with modern data science workflows. Graphviz is a foundational open-source graph visualization package, initially developed at AT&T Labs in the early 1990s and fully released as open source in 2000. It employs the DOT language for graph specification and offers multiple layout engines, including neato and fdp for force-directed methods, circo for circular arrangements, and twopi for radial drawings, with support for planar graph representations using engines such as dot or fdp.[77] Widely adopted for its simplicity and output formats like SVG and PDF, Graphviz integrates well with scripting languages and remains actively maintained on GitHub. NetworkX, a Python library for creating, manipulating, and analyzing complex networks, originated in 2002 at Los Alamos National Laboratory. It provides drawing capabilities through Matplotlib backends and an interface to Graphviz via PyGraphviz, supporting algorithms such as spring_layout for force-directed simulations and planar_layout for straight-line planar drawings.[78] Its seamless integration with Python's data science ecosystem, including libraries like Pandas and SciPy, makes it ideal for network visualization in research and analytics, with ongoing community contributions via GitHub repositories. D3.js (Data-Driven Documents) is a JavaScript library for building interactive web-based visualizations, released in 2011 by Mike Bostock as a successor to the Protovis framework.[79] It excels in dynamic graph drawings through its force simulation module, which implements force-directed layouts with features like node repulsion, link attraction, and collision avoidance for scalable, browser-rendered graphs. D3.js supports planar and hierarchical structures via additional modules like d3-hierarchy, enabling customizable, SVG-based outputs for web applications. The Open Graph Drawing Framework (OGDF) is a comprehensive C++ library dedicated to graph algorithms, launched in 2005 as an open-source evolution of the commercial OGDL.[80] It includes advanced implementations for planar embeddings using methods like the Boyer-Myrvold planarity test and force-directed layouts via multilevel approaches, alongside tools for crossing minimization and layered drawings.[81] OGDF's modular design allows integration into larger C++ projects, with Python bindings available through ogdf-python for broader accessibility in the 2020s.[82] PyGraphviz extends Graphviz's functionality as a Python interface, enabling direct creation, editing, and rendering of DOT-described graphs within Python scripts, with version 1.13 released in 2024 incorporating enhancements for better NumPy compatibility and error handling.[83] It bridges Graphviz's layout engines with Python's ecosystem, supporting force-directed and hierarchical drawings while allowing layout plugins for custom extensions.[84] Community-driven updates on GitHub have focused on 2020s improvements, such as improved Unicode support and integration with Jupyter notebooks for interactive data science workflows.[84]Commercial and Integrated Software

Commercial graph drawing software provides proprietary solutions with built-in support, professional services, and integration capabilities for enterprise environments, often emphasizing ease of use and scalability over open customization.[85] These tools typically incorporate automatic layout algorithms for node-link diagrams, supporting applications from network analysis to optimization modeling.[86] yEd, developed by yWorks, is a free desktop application that enables users to create, import, edit, and automatically arrange high-quality diagrams using proprietary layout engines.[85] It supports various graph types, including hierarchical, orthogonal, and organic layouts, and runs on Windows, macOS, and Unix/Linux platforms without requiring licensing fees, though its core engine remains proprietary.[87] This tool is widely adopted for professional diagramming due to its intuitive interface and export options to formats like PDF and SVG.[88] Microsoft Visio offers robust diagramming features within the Microsoft 365 ecosystem, including templates for flowcharts, organization charts, and network diagrams that visualize graph structures.[86] It supports data-linked diagrams where graph elements update dynamically from sources like Excel, and includes intelligent features for validating structured graphs against rules.[89] Pricing follows a subscription model, with Visio Plan 1 at $5/user/month for web access and Plan 2 at $15/user/month for desktop features, making it suitable for collaborative enterprise use.[86] IBM ILOG Views Graph Layout integrates graph drawing directly into optimization workflows, providing high-level services for readable representations of complex networks in decision support systems.[90] Part of the broader IBM ILOG CPLEX Optimization Studio, it handles node-link visualizations alongside solvers for linear and mixed-integer programming, often used in supply chain and resource allocation scenarios.[91] Licensing is enterprise-focused, with costs varying by deployment scale, typically starting in the thousands for commercial use.[92] In business intelligence platforms, graph drawing is embedded via plugins for network visualization. Tableau supports extensions like the Network Chart Extension, which renders node-link graphs to highlight data relationships, integrable with dashboards for interactive exploration.[93] Similarly, Power BI features the Powerviz Network Graph visual, allowing users to depict vertices and edges from datasets, with support for filtering and drilling down into connections.[94] These integrations prioritize seamless data flow without requiring separate tools. MATLAB's Graph and Network Algorithms toolbox includes functions likegraph for creating undirected graphs and plot for drawing them, enabling visualization of adjacency matrices and edge properties in a computational environment.[95] It supports layered and circular layouts for analyzing connectivity in scientific data, with scalability to thousands of nodes via optimized plotting.[96] Commercial licensing for MATLAB starts at around $2,150 for a base installation, with toolbox add-ons extra.[97]

In cybersecurity, Splunk employs graph visualization through integrations like Graphistry to map network patterns and investigate threats, rendering interactive node-link diagrams from log data for anomaly detection.[98] This setup allows security analysts to explore millions of events, identifying hidden connections in real-time.[99] Splunk's enterprise pricing is usage-based, often exceeding $10,000 annually for mid-scale deployments.

Recent cloud integrations enhance scalability for large graphs. Amazon Neptune, a managed graph database, connects with visualization tools like Graphistry for rendering millions of nodes and relationships, supporting 2024 updates for GPU-accelerated layouts in AWS environments.[100] Similarly, G.V() provides a client for interactive exploration of Neptune data, handling queries on graphs with billions of edges.[101] Tom Sawyer Software, integrated with Neptune, visualizes graphs up to millions of elements, emphasizing performance for enterprise analytics.[102] These solutions scale via cloud resources, with Neptune pricing at $0.20 per million I/O requests for Standard instances plus instance costs starting at $0.036 per hour (e.g., db.t3.small in US East (N. Virginia)) as of November 2025.[103]