Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Hertzsprung–Russell diagram.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hertzsprung–Russell diagram

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Hertzsprung–Russell diagram

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

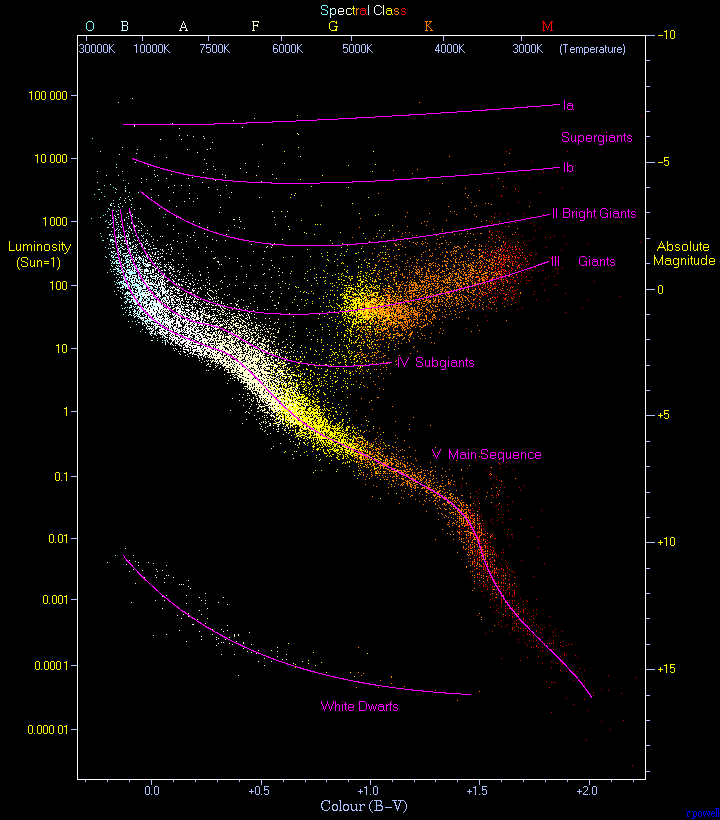

The Hertzsprung–Russell diagram (HR diagram or H–R diagram) is a fundamental astronomical tool that plots stars' luminosity (or absolute magnitude) against their surface temperature (or spectral type), revealing key patterns in stellar properties and evolution.[1] It was independently developed in 1912 by Danish astronomer Ejnar Hertzsprung and American astronomer Henry Norris Russell, using observational data to compare stars' brightness and color.[2]

The diagram's horizontal axis typically runs from hot, blue stars (spectral types O and B, around 30,000–50,000 K) on the left to cool, red stars (types K and M, around 3,000–4,000 K) on the right, while the vertical axis increases upward from low luminosity (dimmer stars) to high luminosity (brighter stars).[3] Approximately 90% of stars cluster along a diagonal band known as the main sequence, where stars like the Sun spend most of their hydrogen-fusing lifetimes, with position determined primarily by mass—hotter, more massive stars at the upper left evolve faster, while cooler, less massive ones at the lower right last longer.[1] Above the main sequence lie the red giants and supergiants, representing later evolutionary stages where stars expand and brighten after exhausting core hydrogen, and below it are the faint white dwarfs, the remnants of low- to medium-mass stars that have shed their outer layers.[3]

This scatter plot not only classifies stars by intrinsic properties but also serves as a cornerstone for understanding stellar life cycles, as it captures snapshots of stars at different ages and masses, enabling predictions about evolution, composition, and even distances via standard candles like Cepheid variables in the instability strip.[1] Developed from early 20th-century spectroscopic data, including classifications by Annie Jump Cannon, the HR diagram remains essential for modern astrophysics, from cluster analysis to galaxy formation studies.[3]