Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Open cluster

View on Wikipedia| Open cluster | |

|---|---|

The Pleiades is among the nearest open clusters to Earth | |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | Loose cluster of stars |

| Size range | < 30 ly in diameter |

| Density | ~ 1.5 stars / cubic ly |

| External links | |

| Additional Information | |

An open cluster is a type of star cluster made of tens to a few thousand stars that were formed from the same giant molecular cloud and have roughly the same age. More than 1,100 open clusters have been discovered within the Milky Way galaxy, and many more are thought to exist.[1] Each one is loosely bound by mutual gravitational attraction and becomes disrupted by close encounters with other clusters and clouds of gas as they orbit the Galactic Center. This can result in a loss of cluster members through internal close encounters and a dispersion into the main body of the galaxy.[2] Open clusters generally survive for a few hundred million years, with the most massive ones surviving for a few billion years. In contrast, the more massive globular clusters of stars exert a stronger gravitational attraction on their members, and can survive for longer. Open clusters have been found only in spiral and irregular galaxies, in which active star formation is occurring.[3]

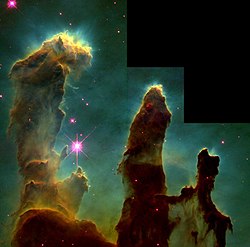

Young open clusters may be contained within the molecular cloud from which they formed, illuminating it to create an H II region.[4] Over time, radiation pressure from the cluster will disperse the molecular cloud. Typically, about 10% of the mass of a gas cloud will coalesce into stars before radiation pressure drives the rest of the gas away.

Open clusters are key objects in the study of stellar evolution. Because the cluster members are of similar age and chemical composition, their properties (such as distance, age, metallicity, extinction, and velocity) are more easily determined than they are for isolated stars.[1] A number of open clusters, such as the Pleiades, the Hyades and the Alpha Persei Cluster, are visible with the naked eye. Some others, such as the Double Cluster, are barely perceptible without instruments, while many more can be seen using binoculars or telescopes. The Wild Duck Cluster, M11, is an example.[5]

Historical observations

[edit]

The prominent open cluster the Pleiades, in the constellation Taurus, has been recognized as a group of stars since antiquity, while the Hyades (which also form part of Taurus) is one of the oldest open clusters. Other open clusters were noted by early astronomers as unresolved fuzzy patches of light. In his Almagest, the Roman astronomer Ptolemy mentions the Praesepe Cluster, the Double Cluster in Perseus, the Coma Star Cluster and the Ptolemy Cluster, while the Persian astronomer Al-Sufi wrote of the Omicron Velorum cluster.[7] However, it would require the invention of the telescope to resolve these "nebulae" into their constituent stars.[8] Indeed, in 1603 Johann Bayer gave three of these clusters designations as if they were single stars.[9]

The first person to use a telescope to observe the night sky and record his observations was the Italian scientist Galileo Galilei in 1609. When he turned the telescope toward some of the nebulous patches recorded by Ptolemy, he found they were not a single star, but groupings of many stars. For Praesepe, he found more than 40 stars. Where previously observers had noted only 6–7 stars in the Pleiades, he found almost 50.[11] In his 1610 treatise Sidereus Nuncius, Galileo Galilei wrote, "the galaxy is nothing else but a mass of innumerable stars planted together in clusters."[12] Influenced by Galileo's work, the Sicilian astronomer Giovanni Hodierna became possibly the first astronomer to use a telescope to find previously undiscovered open clusters.[13] In 1654, he identified the objects now designated Messier 41, Messier 47, NGC 2362 and NGC 2451.[14]

It was realized as early as 1767 that the stars in a cluster were physically related,[15] when English naturalist Reverend John Michell calculated that the probability of even just one group of stars like the Pleiades being the result of a chance alignment as seen from Earth was just 1 in 496,000.[16] Between 1774 and 1781, French astronomer Charles Messier published a catalogue of celestial objects that had a nebulous appearance similar to comets. This catalogue included 26 open clusters.[9] In the 1790s, English astronomer William Herschel began an extensive study of nebulous celestial objects. He discovered that many of these features could be resolved into groupings of individual stars. Herschel conceived the idea that stars were initially scattered across space, but later became clustered together as star systems because of gravitational attraction.[17] He divided the nebulae into eight classes, with classes VI through VIII being used to classify clusters of stars.[18]

The number of clusters known continued to increase under the efforts of astronomers. Hundreds of open clusters were listed in the New General Catalogue, first published in 1888 by the Danish–Irish astronomer J. L. E. Dreyer, and the two supplemental Index Catalogues, published in 1896 and 1905.[9] Telescopic observations revealed two distinct types of clusters, one of which contained thousands of stars in a regular spherical distribution and was found all across the sky but preferentially towards the center of the Milky Way.[19] The other type consisted of a generally sparser population of stars in a more irregular shape. These were generally found in or near the galactic plane of the Milky Way.[20][21] Astronomers dubbed the former globular clusters, and the latter open clusters. Because of their location, open clusters are occasionally referred to as galactic clusters, a term that was introduced in 1925 by the Swiss-American astronomer Robert Julius Trumpler.[22]

Micrometer measurements of the positions of stars in clusters were made as early as 1877 by the German astronomer E. Schönfeld and further pursued by the American astronomer E. E. Barnard prior to his death in 1923. No indication of stellar motion was detected by these efforts.[23] However, in 1918 the Dutch–American astronomer Adriaan van Maanen was able to measure the proper motion of stars in part of the Pleiades cluster by comparing photographic plates taken at different times.[24] As astrometry became more accurate, cluster stars were found to share a common proper motion through space. By comparing the photographic plates of the Pleiades cluster taken in 1918 with images taken in 1943, van Maanen was able to identify those stars that had a proper motion similar to the mean motion of the cluster, and were therefore more likely to be members.[25] Spectroscopic measurements revealed common radial velocities, thus showing that the clusters consist of stars bound together as a group.[1]

The first color–magnitude diagrams of open clusters were published by Ejnar Hertzsprung in 1911, giving the plot for the Pleiades and Hyades star clusters. He continued this work on open clusters for the next twenty years. From spectroscopic data, he was able to determine the upper limit of internal motions for open clusters, and could estimate that the total mass of these objects did not exceed several hundred times the mass of the Sun. He demonstrated a relationship between the star colors and their magnitudes, and in 1929 noticed that the Hyades and Praesepe clusters had different stellar populations than the Pleiades. This would subsequently be interpreted as a difference in ages of the three clusters.[26]

Formation

[edit]

The formation of an open cluster begins with the collapse of part of a giant molecular cloud, a cold dense cloud of gas and dust containing up to many thousands of times the mass of the Sun. These clouds have densities that vary from 102 to 106 molecules of neutral hydrogen per cm3, with star formation occurring in regions with densities above 104 molecules per cm3. Typically, only 1–10% of the cloud by volume is above the latter density.[27] Prior to collapse, these clouds maintain their mechanical equilibrium through magnetic fields, turbulence and rotation.[28]

Many factors may disrupt the equilibrium of a giant molecular cloud, triggering a collapse and initiating the burst of star formation that can result in an open cluster. These include shock waves from a nearby supernova, collisions with other clouds and gravitational interactions. Even without external triggers, regions of the cloud can reach conditions where they become unstable against collapse.[28] The collapsing cloud region will undergo hierarchical fragmentation into ever smaller clumps, including a particularly dense form known as infrared dark clouds, eventually leading to the formation of up to several thousand stars. This star formation begins enshrouded in the collapsing cloud, blocking the protostars from sight but allowing infrared observation.[27] In the Milky Way galaxy, the formation rate of open clusters is estimated to be one every few thousand years.[29]

The hottest and most massive of the newly formed stars (known as OB stars) will emit intense ultraviolet radiation, which steadily ionizes the surrounding gas of the giant molecular cloud, forming an H II region. Stellar winds and radiation pressure from the massive stars begins to drive away the hot ionized gas at a velocity matching the speed of sound in the gas. After a few million years the cluster will experience its first core-collapse supernovae, which will also expel gas from the vicinity. In most cases these processes will strip the cluster of gas within ten million years, and no further star formation will take place. Still, about half of the resulting protostellar objects will be left surrounded by circumstellar disks, many of which form accretion disks.[27]

As only 30 to 40 percent of the gas in the cloud core forms stars, the process of residual gas expulsion is highly damaging to the star formation process. All clusters thus suffer significant infant weight loss, while a large fraction undergo infant mortality. At this point, the formation of an open cluster will depend on whether the newly formed stars are gravitationally bound to each other; otherwise an unbound stellar association will result. Even when a cluster such as the Pleiades does form, it may hold on to only a third of the original stars, with the remainder becoming unbound once the gas is expelled.[30] The young stars so released from their natal cluster become part of the Galactic field population.

Because most if not all stars form in clusters, star clusters are to be viewed as the fundamental building blocks of galaxies. The violent gas-expulsion events that shape and destroy many star clusters at birth leave their imprint in the morphological and kinematical structures of galaxies.[31] Most open clusters form with at least 100 stars and a mass of 50 or more solar masses. The largest clusters can have over 104 solar masses, with the massive cluster Westerlund 1 being estimated at 5 × 104 solar masses and R136 at almost 5 x 105, typical of globular clusters.[27] While open clusters and globular clusters form two fairly distinct groups, there may not be a great deal of intrinsic difference between a very sparse globular cluster such as Palomar 12 and a very rich open cluster. Some astronomers believe the two types of star clusters form via the same basic mechanism, with the difference being that the conditions that allowed the formation of the very rich globular clusters containing hundreds of thousands of stars no longer prevail in the Milky Way.[32]

It is common for two or more separate open clusters to form out of the same molecular cloud. In the Large Magellanic Cloud, both Hodge 301 and R136 have formed from the gases of the Tarantula Nebula, while in our own galaxy, tracing back the motion through space of the Hyades and Praesepe, two prominent nearby open clusters, suggests that they formed in the same cloud about 600 million years ago.[33] Sometimes, two clusters born at the same time will form a binary cluster. The best known example in the Milky Way is the Double Cluster of NGC 869 and NGC 884 (also known as h and χ Persei), but at least 10 more double clusters are known to exist.[34] New research indicates the Cepheid-hosting M25 may constitute a ternary star cluster together with NGC 6716 and Collinder 394.[35] Many more binary clusters are known in the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds—they are easier to detect in external systems than in our own galaxy because projection effects can cause unrelated clusters within the Milky Way to appear close to each other.

Morphology and classification

[edit]

Open clusters range from very sparse clusters with only a few members to large agglomerations containing thousands of stars. They usually consist of quite a distinct dense core, surrounded by a more diffuse 'corona' of cluster members. The core is typically about 3–4 light years across, with the corona extending to about 20 light years from the cluster center. Typical star densities in the center of a cluster are about 1.5 stars per cubic light year. For comparison, stellar density near the Sun is about 0.003 stars per cubic light year.[37]

Open clusters are often classified according to a scheme developed by Robert Trumpler in 1930. The Trumpler scheme gives a cluster a three-part designation, with a Roman numeral from I-IV for little to very disparate, an Arabic numeral from 1 to 3 for the range in brightness of members (from small to large range), and p, m or r to indication whether the cluster is poor, medium or rich in stars. An 'n' is appended if the cluster lies within nebulosity.[38]

Under the Trumpler scheme, the Pleiades are classified as I3rn, and the nearby Hyades are classified as II3m.

Numbers and distribution

[edit]

There are over 1,100 known open clusters in our galaxy, but the true total may be up to ten times higher than that.[39] In spiral galaxies, open clusters are largely found in the spiral arms where gas densities are highest and so most star formation occurs, and clusters usually disperse before they have had time to travel beyond their spiral arm. Open clusters are strongly concentrated close to the galactic plane, with a scale height in our galaxy of about 180 light years, compared with a galactic radius of approximately 50,000 light years.[40]

In irregular galaxies, open clusters may be found throughout the galaxy, although their concentration is highest where the gas density is highest.[41] Open clusters are not seen in elliptical galaxies: Star formation ceased many millions of years ago in ellipticals, and so the open clusters which were originally present have long since dispersed.[42]

In the Milky Way Galaxy, the distribution of clusters depends on age, with older clusters being preferentially found at greater distances from the Galactic Center, generally at substantial distances above or below the galactic plane.[43] Tidal forces are stronger nearer the center of the galaxy, increasing the rate of disruption of clusters, and also the giant molecular clouds which cause the disruption of clusters are concentrated towards the inner regions of the galaxy, so clusters in the inner regions of the galaxy tend to get dispersed at a younger age than their counterparts in the outer regions.[44]

Stellar composition

[edit]

Because open clusters tend to be dispersed before most of their stars reach the end of their lives, the light from them tends to be dominated by the young, hot blue stars. These stars are the most massive, and have the shortest lives, a few tens of millions of years. The older open clusters tend to contain more yellow stars.[45]

The frequency of binary star systems has been observed to be higher within open clusters than outside open clusters. This is seen as evidence that single stars get ejected from open clusters due to dynamical interactions.[46]

Some open clusters contain hot blue stars which seem to be much younger than the rest of the cluster. These blue stragglers are also observed in globular clusters, and in the very dense cores of globulars they are believed to arise when stars collide, forming a much hotter, more massive star. However, the stellar density in open clusters is much lower than that in globular clusters, and stellar collisions cannot explain the numbers of blue stragglers observed. Instead, it is thought that most of them probably originate when dynamical interactions with other stars cause a binary system to coalesce into one star.[47]

Once they have exhausted their supply of hydrogen through nuclear fusion, medium- to low-mass stars shed their outer layers to form a planetary nebula and evolve into white dwarfs. While most clusters become dispersed before a large proportion of their members have reached the white dwarf stage, the number of white dwarfs in open clusters is still generally much lower than would be expected, given the age of the cluster and the expected initial mass distribution of the stars. One possible explanation for the lack of white dwarfs is that when a red giant expels its outer layers to become a planetary nebula, a slight asymmetry in the loss of material could give the star a 'kick' of a few kilometres per second, enough to eject it from the cluster.[48]

Because of their high density, close encounters between stars in an open cluster are common.[citation needed] For a typical cluster with 1,000 stars with a 0.5 parsec half-mass radius, on average a star will have an encounter with another member every 10 million years. The rate is even higher in denser clusters. These encounters can have a significant impact on the extended circumstellar disks of material that surround many young stars. Tidal perturbations of large disks may result in the formation of massive planets and brown dwarfs, producing companions at distances of 100 AU or more from the host star.[49]

Eventual fate

[edit]

Many open clusters are inherently unstable, with a small enough mass that the escape velocity of the system is lower than the average velocity of the constituent stars. These clusters will rapidly disperse within a few million years. In many cases, the stripping away of the gas from which the cluster formed by the radiation pressure of the hot young stars reduces the cluster mass enough to allow rapid dispersal.[50]

Clusters that have enough mass to be gravitationally bound once the surrounding nebula has evaporated can remain distinct for many tens of millions of years, but, over time, internal and external processes tend also to disperse them. Internally, close encounters between stars can increase the velocity of a member beyond the escape velocity of the cluster. This results in the gradual 'evaporation' of cluster members.[51]

Externally, about every half-billion years or so an open cluster tends to be disturbed by external factors such as passing close to or through a molecular cloud. The gravitational tidal forces generated by such an encounter tend to disrupt the cluster. Eventually, the cluster becomes a stream of stars, not close enough to be a cluster but all related and moving in similar directions at similar speeds. The timescale over which a cluster disrupts depends on its initial stellar density, with more tightly packed clusters persisting longer. Estimated cluster half lives, after which half the original cluster members will have been lost, range from 150–800 million years, depending on the original density.[51]

After a cluster has become gravitationally unbound, many of its constituent stars will still be moving through space on similar trajectories, in what is known as a stellar association, moving cluster, or moving group. Several of the brightest stars in the 'Plough' of Ursa Major are former members of an open cluster which now form such an association, in this case the Ursa Major Moving Group.[52] Eventually their slightly different relative velocities will see them scattered throughout the galaxy. A larger cluster is then known as a stream, if we discover the similar velocities and ages of otherwise well-separated stars.[53][54]

Studying stellar evolution

[edit]

When a Hertzsprung–Russell diagram is plotted for an open cluster, most stars lie on the main sequence.[55] The most massive stars have begun to evolve away from the main sequence and are becoming red giants; the position of the turn-off from the main sequence can be used to estimate the age of the cluster.[56]

Because the stars in an open cluster are all at roughly the same distance from Earth, and were born at roughly the same time from the same raw material, the differences in apparent brightness among cluster members are due only to their mass.[55] This makes open clusters very useful in the study of stellar evolution, because when comparing one star with another, many of the variable parameters are fixed.[56]

The study of the abundances of lithium and beryllium in open-cluster stars can give important clues about the evolution of stars and their interior structures. While hydrogen nuclei cannot fuse to form helium until the temperature reaches about 10 million K, lithium and beryllium are destroyed at temperatures of 2.5 million K and 3.5 million K respectively. This means that their abundances depend strongly on how much mixing occurs in stellar interiors. Through study of their abundances in open-cluster stars, variables such as age and chemical composition can be fixed.[57]

Studies have shown that the abundances of these light elements are much lower than models of stellar evolution predict. While the reason for this underabundance is not yet fully understood, one possibility is that convection in stellar interiors can 'overshoot' into regions where radiation is normally the dominant mode of energy transport.[57]

Astronomical distance scale

[edit]

Determining the distances to astronomical objects is crucial to understanding them, but the vast majority of objects are too far away for their distances to be directly determined. Calibration of the astronomical distance scale relies on a sequence of indirect and sometimes uncertain measurements relating the closest objects, for which distances can be directly measured, to increasingly distant objects.[58] Open clusters are a crucial step in this sequence.

The closest open clusters can have their distance measured directly by one of two methods. First, the parallax (the small change in apparent position over the course of a year caused by the Earth moving from one side of its orbit around the Sun to the other) of stars in close open clusters can be measured, like other individual stars. Clusters such as the Pleiades, Hyades and a few others within about 500 light years are close enough for this method to be viable, and results from the Hipparcos position-measuring satellite yielded accurate distances for several clusters.[59][60]

The other direct method is the so-called moving cluster method. This relies on the fact that the stars of a cluster share a common motion through space. Measuring the proper motions of cluster members and plotting their apparent motions across the sky will reveal that they converge on a vanishing point. The radial velocity of cluster members can be determined from Doppler shift measurements of their spectra, and once the radial velocity, proper motion and angular distance from the cluster to its vanishing point are known, simple trigonometry will reveal the distance to the cluster. The Hyades are the best-known application of this method, which reveals their distance to be 46.3 parsecs.[61]

Once the distances to nearby clusters have been established, further techniques can extend the distance scale to more distant clusters. By matching the main sequence on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram for a cluster at a known distance with that of a more distant cluster, the distance to the more distant cluster can be estimated. The nearest open cluster is the Hyades: The stellar association consisting of most of the Plough stars is at about half the distance of the Hyades, but is a stellar association rather than an open cluster as the stars are not gravitationally bound to each other. The most distant known open cluster in our galaxy is Berkeley 29, at a distance of about 15,000 parsecs.[62] Open clusters, especially super star clusters, are also easily detected in many of the galaxies of the Local Group and nearby: e.g., NGC 346 and the SSCs R136 and NGC 1569 A and B.

Accurate knowledge of open cluster distances is vital for calibrating the period–luminosity relationship shown by variable stars such as Cepheid stars, which allows them to be used as standard candles. These luminous stars can be detected at great distances, and are then used to extend the distance scale to nearby galaxies in the Local Group.[63] Indeed, the open cluster designated NGC 7790 hosts three classical Cepheids.[64][65] RR Lyrae variables are too old to be associated with open clusters, and are instead found in globular clusters.

Planets

[edit]The stars in open clusters can host exoplanets, just like stars outside open clusters. For example, the open cluster NGC 6811 contains two known planetary systems, Kepler-66 and Kepler-67. Additionally, several hot Jupiters are known to exist in the Beehive Cluster.[66]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Frommert, Hartmut; Kronberg, Christine (August 27, 2007). "Open Star Clusters". SEDS. University of Arizona, Lunar and Planetary Lab. Archived from the original on December 22, 2008. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Karttunen, Hannu; et al. (2003). Fundamental astronomy. Physics and Astronomy Online Library (4th ed.). Springer. p. 321. ISBN 3-540-00179-4.

- ^ Payne-Gaposchkin, C. (1979). Stars and clusters. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Bibcode:1979stcl.book.....P. ISBN 0-674-83440-2.

- ^ A good example of this is NGC 2244, in the Rosette Nebula. See also Johnson, Harold L. (November 1962). "The Galactic Cluster, NGC 2244". Astrophysical Journal. 136: 1135. Bibcode:1962ApJ...136.1135J. doi:10.1086/147466.

- ^ Neata, Emil. "Open Star Clusters: Information and Observations". Night Sky Info. Archived from the original on 2012-09-08. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ "VISTA Finds 96 Star Clusters Hidden Behind Dust". ESO Science Release. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ^ Moore, Patrick; Rees, Robin (2011), Patrick Moore's Data Book of Astronomy (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 339, ISBN 978-0-521-89935-2

- ^ Jones, Kenneth Glyn (1991). Messier's nebulae and star clusters. Practical astronomy handbook (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0-521-37079-5.

- ^ a b c Kaler, James B. (2006). Cambridge Encyclopedia of Stars. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-521-81803-6.

- ^ "A Star Cluster in the Wake of Carina". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Maran, Stephen P.; Marschall, Laurence A. (2009), Galileo's new universe: the revolution in our understanding of the cosmos, BenBella Books, p. 128, ISBN 978-1-933771-59-5

- ^ D'Onofrio, Mauro; Burigana, Carlo (17 July 2009). "Introduction". In Mauro D'Onofrio; Carlo Burigana (eds.). Questions of Modern Cosmology: Galileo's Legacy. Springer, 2009. p. 1. ISBN 978-3-642-00791-0.

- ^ Fodera-Serio, G.; Indorato, L.; Nastasi, P. (February 1985), "Hodierna's Observations of Nebulae and his Cosmology", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 16 (1): 1, Bibcode:1985JHA....16....1F, doi:10.1177/002182868501600101, S2CID 118328541

- ^ Jones, K. G. (August 1986). "Some Notes on Hodierna's Nebulae". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 17 (50): 187–188. Bibcode:1986JHA....17..187J. doi:10.1177/002182868601700303. S2CID 117590918.

- ^ Chapman, A. (December 1989), "William Herschel and the Measurement of Space", Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 30 (4): 399–418, Bibcode:1989QJRAS..30..399C

- ^ Michell, J. (1767). "An Inquiry into the probable Parallax, and Magnitude, of the Fixed Stars, from the Quantity of Light which they afford us, and the particular Circumstances of their Situation". Philosophical Transactions. 57: 234–264. Bibcode:1767RSPT...57..234M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1767.0028.

- ^ Hoskin, M. (1979). "Herschel, William's Early Investigations of Nebulae – a Reassessment". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 10: 165–176. Bibcode:1979JHA....10..165H. doi:10.1177/002182867901000302. S2CID 125219390.

- ^ Hoskin, M. (February 1987). "Herschel's Cosmology". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 18 (1): 1–34, 20. Bibcode:1987JHA....18....1H. doi:10.1177/002182868701800101. S2CID 125888787.

- ^ Bok, Bart J.; Bok, Priscilla F. (1981). The Milky Way. Harvard books on astronomy (5th ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 136. ISBN 0-674-57503-2.

- ^ Binney, James; Merrifield, Michael (1998), Galactic astronomy, Princeton series in astrophysics, Princeton University Press, p. 377, ISBN 0-691-02565-7

- ^ Basu, Baidyanath (2003). An Introduction to Astrophysics. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 218. ISBN 81-203-1121-3.

- ^ Trumpler, R. J. (December 1925). "Spectral Types in Open Clusters". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 37 (220): 307. Bibcode:1925PASP...37..307T. doi:10.1086/123509. S2CID 122892308.

- ^ Barnard, E. E. (1931), "Micrometric measures of star clusters", Publications of the Yerkes Observatory, 6: 1–106, Bibcode:1931PYerO...6....1B

- ^ van Maanen, Adriaan (1919), "No. 167. Investigations on proper motion. Furst paper: The motions of 85 stars in the neighborhood of Atlas and Pleione", Contributions from the Mount Wilson Observatory, 167, Carnegie Institution of Washington: 1–15, Bibcode:1919CMWCI.167....1V

- ^ van Maanen, Adriaan (July 1945), "Investigations on Proper Motion. XXIV. Further Measures in the Pleiades Cluster", Astrophysical Journal, 102: 26–31, Bibcode:1945ApJ...102...26V, doi:10.1086/144736

- ^ Strand, K. Aa. (December 1977), "Hertzsprung's Contributions to the HR Diagram", in Philip, A. G. Davis; DeVorkin, David H. (eds.), The HR Diagram, In Memory of Henry Norris Russell, IAU Symposium No. 80, held November 2, 1977, vol. 80, National Academy of Sciences, Washington, DC, pp. 55–59, Bibcode:1977IAUS...80S..55S

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Lada, C. J. (January 2010), "The physics and modes of star cluster formation: observations", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 368 (1913): 713–731, arXiv:0911.0779, Bibcode:2010RSPTA.368..713L, doi:10.1098/rsta.2009.0264, PMID 20083503, S2CID 20180097

- ^ a b Shu, Frank H.; Adams, Fred C.; Lizano, Susana (1987), "Star formation in molecular clouds – Observation and theory", Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 25: 23–81, Bibcode:1987ARA&A..25...23S, doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.25.090187.000323

- ^ Battinelli, P.; Capuzzo-Dolcetta, R. (1991). "Formation and evolutionary properties of the Galactic open cluster system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 249: 76–83. Bibcode:1991MNRAS.249...76B. doi:10.1093/mnras/249.1.76.

- ^ Kroupa, Pavel; Aarseth, Sverre; Hurley, Jarrod (March 2001), "The formation of a bound star cluster: from the Orion nebula cluster to the Pleiades", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 321 (4): 699–712, arXiv:astro-ph/0009470, Bibcode:2001MNRAS.321..699K, doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2001.04050.x, S2CID 11660522

- ^ Kroupa, P. (October 4–7, 2004). "The Fundamental Building Blocks of Galaxies". In C. Turon; K.S. O'Flaherty; M.A.C. Perryman (eds.). Proceedings of the Gaia Symposium "The Three-Dimensional Universe with Gaia (ESA SP-576). Observatoire de Paris-Meudon (published 2005). p. 629. arXiv:astro-ph/0412069. Bibcode:2005ESASP.576..629K.

- ^ Elmegreen, Bruce G.; Efremov, Yuri N. (1997). "A Universal Formation Mechanism for Open and Globular Clusters in Turbulent Gas". The Astrophysical Journal. 480 (1): 235–245. Bibcode:1997ApJ...480..235E. doi:10.1086/303966.

- ^ Eggen, O. J. (1960). "Stellar groups, VII. The structure of the Hyades group". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 120 (6): 540–562. Bibcode:1960MNRAS.120..540E. doi:10.1093/mnras/120.6.540.

- ^ Subramaniam, A.; Gorti, U.; Sagar, R.; Bhatt, H. C. (1995). "Probable binary open star clusters in the Galaxy". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 302: 86–89. Bibcode:1995A&A...302...86S.

- ^ Majaess, D.; et al. (August 2024), "A Rare Cepheid-hosting Open Cluster Triad in Sagittarius", Research Notes of the AAS, 8 (8): 205, Bibcode:2024RNAAS...8..205M, doi:10.3847/2515-5172/ad7139.

- ^ "Buried in the Heart of a Giant". Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Nilakshi, S.R.; Pandey, A.K.; Mohan, V. (2002). "A study of spatial structure of galactic open star clusters". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 383 (1): 153–162. Bibcode:2002A&A...383..153N. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011719.

- ^ Trumpler, R.J. (1930). "Preliminary results on the distances, dimensions and space distribution of open star clusters". Lick Observatory Bulletin. 14 (420). Berkeley: University of California Press: 154–188. Bibcode:1930LicOB..14..154T. doi:10.5479/ADS/bib/1930LicOB.14.154T.

- ^ Dias, W.S.; Alessi, B.S.; Moitinho, A.; Lépine, J.R.D. (2002). "New catalogue of optically visible open clusters and candidates". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 389 (3): 871–873. arXiv:astro-ph/0203351. Bibcode:2002A&A...389..871D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20020668. S2CID 18502004.

- ^ Janes, K.A.; Phelps, R.L. (1980). "The galactic system of old star clusters: The development of the galactic disk". The Astronomical Journal. 108: 1773–1785. Bibcode:1994AJ....108.1773J. doi:10.1086/117192.

- ^ Hunter, D. (1997). "Star Formation in Irregular Galaxies: A Review of Several Key Questions". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 109: 937–950. Bibcode:1997PASP..109..937H. doi:10.1086/133965.

- ^ Binney, J.; Merrifield, M. (1998). Galactic Astronomy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02565-0. OCLC 39108765.

- ^ Friel, Eileen D. (1995). "The Old Open Clusters Of The Milky Way". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 33: 381–414. Bibcode:1995ARA&A..33..381F. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.33.090195.002121.

- ^ van den Bergh, S.; McClure, R.D. (1980). "Galactic distribution of the oldest open clusters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 88: 360. Bibcode:1980A&A....88..360V.

- ^ Stefanie Waldek (2021-10-06). "What are star clusters?". Space.com. Retrieved 2024-07-19.

- ^ Torres, Guillermo; Latham, David W.; Quinn, Samuel N. (2021). "Long-term Spectroscopic Survey of the Pleiades Cluster: The Binary Population". The Astrophysical Journal. 921 (2): 117. arXiv:2107.10259. Bibcode:2021ApJ...921..117T. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/ac1585. S2CID 236171384.

- ^ Andronov, N.; Pinsonneault, M.; Terndrup, D. (2003). "Formation of Blue Stragglers in Open Clusters". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 35: 1343. Bibcode:2003AAS...203.8504A.

- ^ Fellhauer, M.; Lin, D.N.C.; Bolte, M.; Aarseth, S.J.; Williams K.A. (2003). "The White Dwarf Deficit in Open Clusters: Dynamical Processes". The Astrophysical Journal. 595 (1): L53–L56. arXiv:astro-ph/0308261. Bibcode:2003ApJ...595L..53F. doi:10.1086/379005. S2CID 15439614.

- ^ Thies, Ingo; Kroupa, Pavel; Goodwin, Simon P.; Stamatellos, Dimitrios; Whitworth, Anthony P. (July 2010), "Tidally Induced Brown Dwarf and Planet Formation in Circumstellar Disks", The Astrophysical Journal, 717 (1): 577–585, arXiv:1005.3017, Bibcode:2010ApJ...717..577T, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/717/1/577, S2CID 3438729

- ^ Hills, J. G. (February 1, 1980). "The effect of mass loss on the dynamical evolution of a stellar system – Analytic approximations". Astrophysical Journal. 235 (1): 986–991. Bibcode:1980ApJ...235..986H. doi:10.1086/157703.

- ^ a b de La Fuente, M.R. (1998). "Dynamical Evolution of Open Star Clusters". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 110 (751): 1117. Bibcode:1998PASP..110.1117D. doi:10.1086/316220.

- ^ Soderblom, David R.; Mayor, Michel (1993). "Stellar kinematic groups. I – The Ursa Major group". Astronomical Journal. 105 (1): 226–249. Bibcode:1993AJ....105..226S. doi:10.1086/116422. ISSN 0004-6256.

- ^ Majewski, S. R.; Hawley, S. L.; Munn, J. A. (1996). "Moving Groups, Stellar Streams and Phase Space Substructure in the Galactic Halo". ASP Conference Series. 92: 119. Bibcode:1996ASPC...92..119M.

- ^ Sick, Jonathan; de Jong, R. S. (2006). "A New Method for Detecting Stellar Streams in the Halos of Galaxies". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 38: 1191. Bibcode:2006AAS...20921105S.

- ^ a b "Diagrammi degli ammassi ed evoluzione stellare" (in Italian). O.R.S.A. – Organizzazione Ricerche e Studi di Astronomia. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b Carroll, B. W.; Ostlie, D. A. (2017). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 476–477. ISBN 978-1-108-42216-1.

- ^ a b VandenBerg, D.A.; Stetson, P.B. (2004). "On the Old Open Clusters M67 and NGC 188: Convective Core Overshooting, Color–Temperature Relations, Distances, and Ages". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 116 (825): 997–1011. Bibcode:2004PASP..116..997V. doi:10.1086/426340.

- ^ Keel, Bill. "The Extragalactic Distance Scale". Department of Physics and Astronomy – University of Alabama. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ^ Brown, A.G.A. (2001). "Open clusters and OB associations: a review". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. 11: 89–96. Bibcode:2001RMxAC..11...89B.

- ^ Percival, S. M.; Salaris, M.; Kilkenny, D. (2003). "The open cluster distance scale – A new empirical approach". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 400 (2): 541–552. arXiv:astro-ph/0301219. Bibcode:2003A&A...400..541P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20030092. S2CID 10544370.

- ^ Hanson, R.B. (1975). "A study of the motion, membership, and distance of the Hyades cluster". Astronomical Journal. 80: 379–401. Bibcode:1975AJ.....80..379H. doi:10.1086/111753.

- ^ Bragaglia, A.; Held, E.V.; Tosi M. (2005). "Radial velocities and membership of stars in the old, distant open cluster Berkeley 29". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 429 (3): 881–886. arXiv:astro-ph/0409046. Bibcode:2005A&A...429..881B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041049. S2CID 16669438.

- ^ Rowan-Robinson, Michael (March 1988). "The extragalactic distance scale". Space Science Reviews. 48 (1–2): 1–71. Bibcode:1988SSRv...48....1R. doi:10.1007/BF00183129. ISSN 0038-6308. S2CID 121736592.

- ^ Sandage, Allan (1958). Cepheids in Galactic Clusters. I. CF Cass in NGC 7790., AJ, 128

- ^ Majaess, D.; Carraro, G.; Moni Bidin, C.; Bonatto, C.; Berdnikov, L.; Balam, D.; Moyano, M.; Gallo, L.; Turner, D.; Lane, D.; Gieren, W.; Borissova, J.; Kovtyukh, V.; Beletsky, Y. (2013). Anchors for the cosmic distance scale: the Cepheids U Sagittarii, CF Cassiopeiae, and CEab Cassiopeiae, A&A, 260

- ^ Quinn, Samuel N.; White, Russel J.; Latham, David W.; Buchhave, Lars A.; Cantrell, Justin R.; Dahm, Scott E.; Fűrész, Gabor; Szentgyorgyi, Andrew H.; Geary, John C.; Torres, Guillermo; Bieryla, Allyson; Berlind, Perry; Calkins, Michael C.; Esquerdo, Gilbert A.; Stefanik, Robert P. (2012-08-22). "Two 'b's in the Beehive: The Discovery of the First Hot Jupiters in an Open Cluster". The Astrophysical Journal. 756 (2). The American Astronomical Society: L33. arXiv:1207.0818. Bibcode:2012ApJ...756L..33Q. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/756/2/L33. S2CID 118825401.

Further reading

[edit]- Kaufmann, W. J. (1994). Universe. W H Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-2379-4.

- Smith, E.V.P.; Jacobs, K.C.; Zeilik, M.; Gregory, S.A. (1997). Introductory Astronomy and Astrophysics. Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-03-006228-4.

External links

[edit]- The Jewel Box (also known as NGC 4755 or Kappa Crucis Cluster) – open cluster in the Crux constellation @ SKY-MAP.ORG

- Open Star Clusters @ SEDS Messier pages

- A general overview of open clusters

- The moving cluster method

- Open Clusters – Information and amateur observations Archived 2007-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

Open cluster

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and History

Definition and Characteristics

Open clusters are loosely bound groups of tens to a few thousand stars that formed simultaneously from the same giant molecular cloud, sharing similar ages ranging from a few million to up to about 10 billion years, though most are under a billion years old.[8][1][9] These stellar aggregates typically contain 50 to 1,000 members and are held together by mutual gravitational attraction, though their low binding energy results in gradual dispersal over time due to internal dynamics and external perturbations.[9][10] Key physical properties of open clusters include diameters generally spanning 3 to 30 light-years, with a dense core of a few light-years surrounded by an extended corona, and total masses between 10² and 10⁴ solar masses.[9][8][10] They reside predominantly in the disk and spiral arms of galaxies like the Milky Way, where star formation is active.[8] Prominent examples include the Pleiades, visible to the naked eye as a hazy patch in Taurus and containing around 1,000 stars at about 440 light-years away, and the Hyades, the nearest open cluster at 153 light-years, also observable without aid and marking the bull's face.[11][12] In contrast to globular clusters, open clusters are younger (typically under a billion years old), less dense, and exhibit irregular shapes rather than the spherical, tightly packed configurations of globulars, which are ancient (8–13 billion years) and located in galactic halos with tens of thousands to millions of stars.[8][1] Observationally, open clusters appear as diffuse, fuzzy concentrations in telescopes, often dominated by the bright light of hot, blue main-sequence stars, though they encompass a full range of spectral types from O-type stars to low-mass red dwarfs.[8][13]Historical Observations

Open clusters have been recognized by astronomers since antiquity, with prominent examples like the Pleiades noted in ancient Greek texts as the "Seven Sisters." Referenced in the works of Homer and Hesiod around the 8th century BCE, the Pleiades were described as a cohesive group of stars associated with mythological figures, daughters of the Titan Atlas.[14] Similarly, the Hyades and Praesepe (Beehive Cluster) appear in early Greek compilations of constellations, highlighting their visibility and cultural significance as recognizable stellar groupings without telescopic aid.[14] These early naked-eye observations laid the foundation for later systematic studies, though the true nature of clusters as bound stellar associations remained unrecognized. The advent of the telescope in the early 17th century marked a pivotal advancement in open cluster observations. In 1610, Galileo Galilei turned his rudimentary telescope toward the Pleiades, resolving dozens of faint stars beyond the six or seven visible to the unaided eye, demonstrating the multiplicity within such groupings and challenging prior perceptions of isolated stars.[15] By the 18th century, Charles Messier compiled his renowned catalog of nebulae and star clusters between 1758 and 1782, primarily to avoid mistaking these diffuse objects for comets during his hunts; it included several open clusters, such as M45 (Pleiades), M44 (Praesepe), and M37, cataloging 27 open clusters in total among its 110 entries.[16] In the late 18th century, William Herschel expanded these efforts through systematic sweeps of the sky using larger telescopes. From 1783 to 1802, he cataloged over 2,500 nebulae and star clusters, classifying them into eight classes based on appearance and resolvability; open clusters fell into categories like Class VII (pretty much compressed clusters of large or small stars) and Class VIII (coarsely scattered clusters of stars), where he introduced the term "resolvable nebulae" for hazy patches that telescopes revealed as aggregations of individual stars.[17] Herschel's work emphasized the structural diversity of these objects, distinguishing loosely scattered groups from denser formations and providing the first large-scale inventory that informed subsequent classifications.[18] The 19th and early 20th centuries brought quantitative advances through photometry and astrometry. In 1930, Robert Trumpler applied photoelectric photometry to a sample of open clusters, deriving their distances, dimensions, and space distribution; this revealed their concentration toward the galactic plane, contrasting with the halo distribution of globular clusters, and provided initial evidence for interstellar dust absorption dimming their light.[19] Harlow Shapley, building on variable star calibrations, estimated distances to open clusters in the 1920s and 1930s, integrating them into broader galactic structure models alongside globulars.[20] Concurrently, catalogs proliferated: Philibert Melotte's 1926 list identified new star clusters and nebulae from Franklin-Adams chart plates, expanding the known inventory of southern objects, while Per Collinder's 1931 dissertation cataloged 471 open clusters, analyzing their structural properties like angular diameter and stellar density to map their galactic distribution.[21] Early proper motion studies in the 1920s and 1930s further refined cluster membership by measuring stellar velocities relative to the background field. Pioneered through photographic plate comparisons, these efforts—outlined in historical reviews—identified co-moving stars as true members, excluding interlopers and enabling precise delineation of cluster boundaries for the first time. Such techniques, applied to catalogs like Collinder's, transformed open clusters from visual curiosities into tools for probing galactic dynamics and evolution.Formation and Structure

Formation Mechanisms

Open clusters originate from the gravitational collapse of giant molecular clouds (GMCs), which typically have masses ranging from to solar masses.[22] These clouds, composed primarily of molecular hydrogen and dust, become unstable under the influence of external triggers such as shock waves from supernovae explosions, compression by spiral density waves in galactic disks, or collisions between clouds.[23] Once triggered, the Jeans instability—a criterion where gravitational forces overcome thermal pressure—drives the fragmentation of the cloud into smaller, denser regions capable of further collapse.[24] The star formation process within these collapsing GMCs proceeds rapidly, beginning with the formation of protostellar cores that preferentially produce massive stars first due to their shorter accretion timescales. These massive stars then exert feedback through intense stellar winds, radiation, and eventual supernovae, which heat and disperse the surrounding gas, halting further collapse and limiting the overall star formation efficiency to approximately 10-30% of the initial cloud mass.[22] The stellar mass distribution in these nascent clusters follows the initial mass function (IMF), empirically described by the Salpeter IMF where the number of stars per mass interval scales as for masses above about 1 solar mass. Clusters often form hierarchically, with sub-clumps of stars and gas merging over time to build the final structure.[25] Numerical simulations, including N-body dynamics for stellar interactions and hydrodynamic models for gas evolution, have elucidated these processes by replicating the turbulent environment of GMCs.[26] Turbulence plays a key role in regulating density fluctuations and ultimately dispersing the residual gas within roughly 10 million years after the onset of star formation.[25] The entire formation timescale spans 1-10 million years, during which clusters remain embedded in their natal nebulae for about 3-5 million years before emerging as exposed associations.[27]Morphology and Classification

Open clusters exhibit diverse morphologies that reflect their structural organization and early dynamical states, ranging from loose, irregular configurations to tightly packed, concentrated groups. Irregular or sparse types, exemplified by the Pleiades (M45), feature stars distributed over an extended area with minimal central density, often appearing as a diffuse grouping against the background field. In contrast, concentrated clusters like the Jewel Box (NGC 4755) display a prominent dense core surrounded by a sparser halo, with brighter, more massive stars centralized. Embedded clusters, such as the Orion Nebula Cluster (ONC), remain shrouded in residual molecular cloud material and dust, making them prominent in infrared observations and characterized by high stellar densities within compact regions of a few parsecs. Denser open clusters frequently possess a core-halo structure, where the core contains the majority of luminous members at high density, while the halo extends outward with gradually decreasing stellar numbers. Classification schemes for open clusters emphasize observable features like density, richness, and environmental context. The classic Trumpler system, developed in the 1930s, categorizes clusters by concentration (classes I–IV, from strongly concentrated with central condensation to barely perceptible against the background), number of member stars (1–3, from few to many), and range of magnitudes (p for small/poor, m for moderate, r for large/rich); an additional 'n' denotes noticeable nebulosity. Clusters are separately grouped by galactic latitude (p for high |b|>20°, n for middle 5°<|b|<20°, g for low |b|<5°). For instance, the Pleiades is classified as II 3 r (moderate concentration, many stars, large magnitude range) and is a p-type (high latitude) cluster, while the Jewel Box is I 3 r (strong concentration, many stars, large magnitude range). Modern approaches include age-based groupings, dividing clusters into young (<100 Myr, often embedded or compact), intermediate (100–500 Myr, showing emerging structure), and old (>500 Myr, more dispersed); this aids in tracing evolutionary changes. Another contemporary scheme distinguishes concentrated (bound, core-dominated) from unclustered (loose associations of stars without clear boundaries), highlighting differences in dynamical stability.[28] Key structural parameters quantify these morphologies and facilitate comparisons. The core radius (), defined as the distance enclosing half the projected cluster mass or density dropping to half its central value, typically ranges from 1 to 5 pc in open clusters, with smaller values in young, dense systems like the ONC ( pc). The half-light radius measures the extent containing half the cluster's light, often comparable to in concentrated types. The concentration parameter , where is the tidal radius marking the boundary influenced by galactic tides, indicates compactness; values of are common for bound open clusters, with lower signaling loosening structures. Morphological evolution begins with initial compactness inherited from parent molecular clouds, but dynamical relaxation processes—such as two-body encounters—cause the core to expand and sphericalize over tens of millions of years. The outer envelope loosens further under the influence of galactic tides, which can elongate halos and strip peripheral stars, particularly in clusters near the disk plane; this leads to more irregular shapes in older systems.Galactic Distribution

Numbers and Locations

Open clusters are primarily distributed within the thin disk of the Milky Way, with the vast majority concentrated within approximately 1 kpc of the galactic plane.[29] Their spatial arrangement traces the galaxy's spiral structure, showing enhanced densities along major arms such as the Perseus Arm, Orion Arm, and Sagittarius Arm.[30] Radially, the distribution exhibits a gradient that peaks between 7 and 9 kpc from the galactic center, reflecting the density wave patterns that drive star formation.[31] The vertical scale height of this population is roughly 100 pc, though it varies with age, remaining smaller (~70 pc) for younger clusters and increasing slightly for intermediate-age ones.[30] As of 2025, major catalogs such as the Milky Way Star Clusters (MWSC) list over 3,000 confirmed open clusters in the Milky Way, while the Unified Cluster Catalogue (UCC) compiles nearly 14,000 objects, including candidates.[32][33] Estimates for the total population range from 30,000 to 100,000, accounting for obscured clusters in the galactic plane and those beyond current detection limits.[34] Additional discoveries from post-2023 Gaia analyses have added hundreds more candidates, further expanding the inventory.[35] The European Space Agency's Gaia mission has significantly expanded this inventory; its Data Release 3 (DR3) in 2022 identified approximately 1,000 new candidates through analysis of proper motions and parallaxes, particularly in the solar neighborhood up to 5 kpc.[36] Beyond the Milky Way, open clusters are observed in nearby galaxies, though in smaller numbers due to increasing distances limiting resolution. The Magellanic Clouds host hundreds of such clusters; the Large Magellanic Cloud alone contains over 700 confirmed open clusters, which serve as key tracers of its star formation history across different epochs.[37] In more distant systems like M31 (Andromeda), only a few dozen are resolved, highlighting their utility in comparative studies of galactic evolution.Stellar Populations and Composition

Open clusters are characterized by a high degree of age homogeneity among their member stars, which form coevally from the collapse of a single molecular cloud, typically within a few million years. This shared origin allows for accurate age determinations via isochrone fitting to the cluster's color-magnitude diagram, where theoretical evolutionary tracks are overlaid to match the observed stellar distribution in the Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) diagram.[38] Such fitting reveals ages ranging from a few million years to several gigayears, with the main-sequence turnoff point serving as a primary indicator: for example, an A-type turnoff corresponds to an age of approximately 200 Myr.[39] Young clusters (ages <100 Myr) are dominated by hot, massive O and B-type stars, which ionize surrounding gas and produce prominent H II regions, while older clusters (>1 Gyr) feature predominantly cooler G and K-type dwarfs as higher-mass stars evolve away from the main sequence.[40] Spectral diversity in open clusters arises from the initial mass function and subsequent evolution, with binaries comprising 30–50% of systems and contributing to the observed scatter in HR diagrams. In older clusters, white dwarfs emerge as a significant population, representing the cooled remnants of stars with initial masses of 1–8 solar masses that have completed core helium burning and subsequent phases.[41] Cluster-specific HR diagrams highlight these evolutionary sequences, from the zero-age main sequence to the red giant branch, often showing mass segregation where massive stars sink toward the cluster center due to dynamical relaxation, with up to 50% of the most massive members concentrated centrally even in clusters as young as 10 Myr.[42] The chemical composition of open clusters reflects their birth environment in the Galactic disk, with typical metallicities near solar ([Fe/H] ≈ 0) and radial gradients indicating metal-richer inner clusters (slope ≈ -0.048 dex kpc⁻¹ for [Fe/H]).[43] Similar gradients appear for α-elements like Mg and Si, while some young clusters, such as NGC 6705 (age ≈ 300 Myr), display enhancements ([α/Fe] > 0.1 dex) that challenge simple chemical evolution models and suggest localized enrichment from nearby supernovae.[44] Special populations include blue stragglers, which appear brighter and bluer than the main-sequence turnoff and are widely interpreted as merger products of two main-sequence stars, retaining excess mass and helium from the collision.[45] Recent observations have identified λ Boo stars—metal-poor A-type stars with depleted iron-peak elements but near-solar C and O—as cluster members for the first time, including HD 28548 in the young cluster HSC 1640 (age ≈ 26 Myr), providing new insights into their formation mechanisms possibly linked to accretion in low-metallicity environments.[46]Dynamical Evolution

Eventual Fate and Dissolution

Open clusters typically survive for timescales ranging from about 100 million years to 1–3 billion years, with approximately 90% dispersing within 1 Gyr primarily due to their low velocity dispersions of 1–2 km/s, which allow internal dynamical processes to dominate early disruption.[47][48][49] Internal dynamics play a central role in cluster dissolution through two-body relaxation, which randomizes stellar velocities and leads to evaporation as stars gain enough energy to escape the cluster's potential. The relaxation timescale is given by [50]where is the number of stars, is the cluster radius, and is the typical stellar velocity; for typical open clusters with – and radii of a few parsecs, this timescale is on the order of 10–100 Myr, driving gradual mass loss via escapers at a rate of about 1–3% per relaxation time.[51] Additionally, mass loss from stellar evolution contributes 10–20% over the cluster's lifetime, as massive stars evolve off the main sequence and eject material through winds and supernovae, further loosening the cluster's binding.[52] External forces accelerate disruption through interactions with the galactic environment, including tidal shocks from passages through the galactic disk every ~100 Myr, which inject energy and strip stars from the cluster's outskirts. Encounters with giant molecular clouds, occurring on similar timescales, can impart impulsive shocks that increase the escape fraction by up to 10–20% per event, while corotation resonances with spiral arms amplify these effects by enhancing density contrasts and tidal stresses.[53][54][55] The end states of dissolving open clusters are primarily contributions to the galactic field star population or extended structures such as tidal tails and streams, as seen in the intermediate-aged Coma Berenices cluster, where escaping stars form observable tails spanning several degrees. Rare remnants persist as old open clusters, such as NGC 6791, which has survived for approximately 8 Gyr due to its favorable orbit and initial conditions.[56][57] Factors influencing survival include the cluster's initial mass and density; simulations demonstrate that clusters with masses exceeding endure longer owing to deeper potentials that resist both internal relaxation and external perturbations, with survival probabilities increasing by factors of 2–5 compared to lower-mass systems.[58]