Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Main sequence

View on Wikipedia

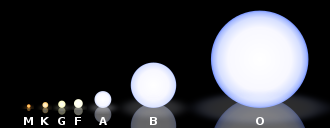

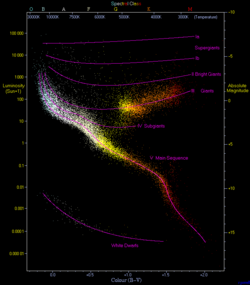

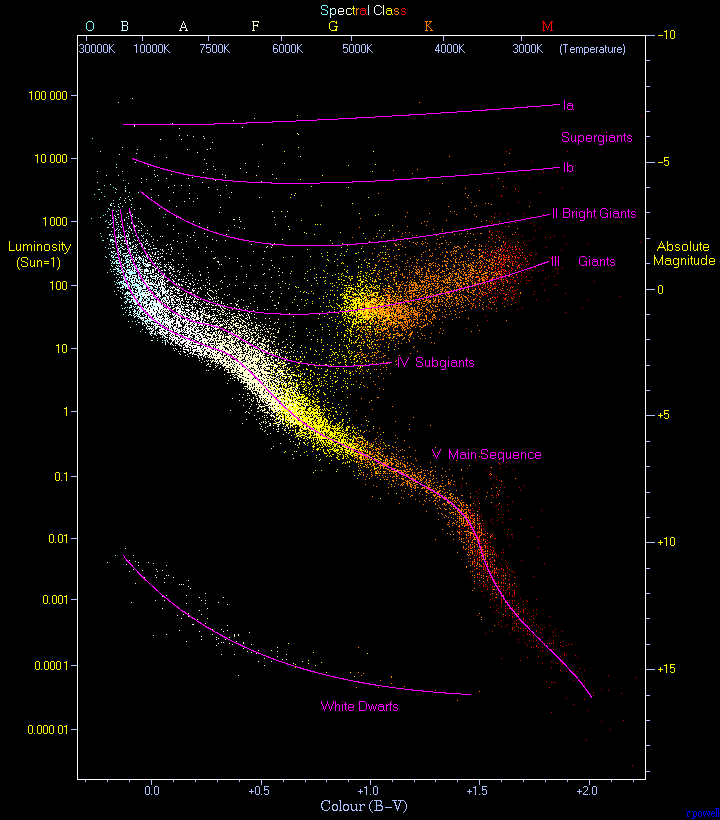

In astronomy, the main sequence is a classification of stars which appear on plots of stellar color versus brightness as a continuous and distinctive band. Stars on this band are known as main-sequence stars or dwarf stars, and positions of stars on and off the band are believed to indicate their physical properties, as well as their progress through several types of star life-cycles. These are the most numerous true stars in the universe and include the Sun. Color-magnitude plots are known as Hertzsprung–Russell diagrams after Ejnar Hertzsprung and Henry Norris Russell.

After condensation and ignition of a star, it generates thermal energy in its dense core region through nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium. During this stage of the star's lifetime, it is located on the main sequence at a position determined primarily by its mass but also based on its chemical composition and age. The cores of main-sequence stars are in hydrostatic equilibrium, where outward thermal pressure from the hot core is balanced by the inward pressure of gravitational collapse from the overlying layers. The strong dependence of the rate of energy generation on temperature and pressure helps to sustain this balance. Energy generated at the core makes its way to the surface and is radiated away at the photosphere. The energy is carried by either radiation or convection, with the latter occurring in regions with steeper temperature gradients, higher opacity, or both.

The main sequence is sometimes divided into upper and lower parts, based on the dominant process that a star uses to generate energy. The Sun, along with main sequence stars below about 1.5 times the mass of the Sun (1.5 M☉), primarily fuse hydrogen atoms together in a series of stages to form helium, a sequence called the proton–proton chain. Above this mass, in the upper main sequence, the nuclear fusion process mainly uses atoms of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as intermediaries in the CNO cycle that produces helium from hydrogen atoms. Main-sequence stars with more than two solar masses undergo convection in their core regions, which acts to stir up the newly created helium and maintain the proportion of fuel needed for fusion to occur. Below this mass, stars have cores that are entirely radiative with convective zones near the surface. With decreasing stellar mass, the proportion of the star forming a convective envelope steadily increases. The main-sequence stars below 0.4 M☉ undergo convection throughout their mass. When core convection does not occur, a helium-rich core develops surrounded by an outer layer of hydrogen.

The more massive a star is, the shorter its lifespan on the main sequence. After the hydrogen fuel at the core has been consumed, the star evolves away from the main sequence on the HR diagram, into a supergiant, red giant, or directly to a white dwarf.

History

[edit]In the early part of the 20th century, information about the types and distances of stars became more readily available. The spectra of stars were shown to have distinctive features, which allowed them to be categorized. Annie Jump Cannon and Edward Charles Pickering at Harvard College Observatory developed a method of categorization that became known as the Harvard Classification Scheme, published in the Harvard Annals in 1901.[1]

In Potsdam in 1906, the Danish astronomer Ejnar Hertzsprung noticed that the reddest stars—classified as K and M in the Harvard scheme—could be divided into two distinct groups. These stars are either much brighter than the Sun or much fainter. To distinguish these groups, he called them "giant" and "dwarf" stars. The following year he began studying star clusters; large groupings of stars that are co-located at approximately the same distance. For these stars, he published the first plots of color versus luminosity. These plots showed a prominent and continuous sequence of stars, which he named the Main Sequence.[2]

At Princeton University, Henry Norris Russell was following a similar course of research. He was studying the relationship between the spectral classification of stars and their actual brightness as corrected for distance—their absolute magnitude. For this purpose, he used a set of stars that had reliable parallaxes and many of which had been categorized at Harvard. When he plotted the spectral types of these stars against their absolute magnitude, he found that dwarf stars followed a distinct relationship. This allowed the real brightness of a dwarf star to be predicted with reasonable accuracy.[3]

Of the red stars observed by Hertzsprung, the dwarf stars also followed the spectra-luminosity relationship discovered by Russell. However, giant stars are much brighter than dwarfs and so do not follow the same relationship. Russell proposed that "giant stars must have low density or great surface brightness, and the reverse is true of dwarf stars". The same curve also showed that there were very few faint white stars.[3]

In 1933, Bengt Strömgren introduced the term Hertzsprung–Russell diagram to denote a luminosity-spectral class diagram.[4] This name reflected the parallel development of this technique by both Hertzsprung and Russell earlier in the century.[2]

As evolutionary models of stars were developed during the 1930s, it was shown that, for stars with the same composition, the star's mass determines its luminosity and radius. Conversely, when a star's chemical composition and its position on the main sequence are known, the star's mass and radius can be deduced. This became known as the Vogt–Russell theorem; named after Heinrich Vogt and Henry Norris Russell. It was subsequently discovered that this relationship breaks down somewhat for stars of the non-uniform composition.[5]

A refined scheme for stellar classification was published in 1943 by William Wilson Morgan and Philip Childs Keenan.[6] The MK classification assigned each star a spectral type—based on the Harvard classification—and a luminosity class. The Harvard classification had been developed by assigning a different letter to each star based on the strength of the hydrogen spectral line before the relationship between spectra and temperature was known. When ordered by temperature and when duplicate classes were removed, the spectral types of stars followed, in order of decreasing temperature with colors ranging from blue to red, the sequence O, B, A, F, G, K, and M. (A popular mnemonic for memorizing this sequence of stellar classes is "Oh Be A Fine Girl/Guy, Kiss Me".) The luminosity class ranged from I to V, in order of decreasing luminosity. Stars of luminosity class V belonged to the main sequence.[7]

In April 2018, astronomers reported the detection of the most distant "ordinary" (i.e., main sequence) star, named Icarus (formally, MACS J1149 Lensed Star 1), at 9 billion light-years away from Earth.[8][9]

Formation and evolution

[edit]| Star formation |

|---|

|

| Object classes |

| Theoretical concepts |

When a protostar is formed from the collapse of a giant molecular cloud of gas and dust in the local interstellar medium, the initial composition is homogeneous throughout, consisting of about 70% hydrogen, 28% helium, and trace amounts of other elements, by mass.[10] The initial mass of the star depends on the local conditions within the cloud. (The mass distribution of newly formed stars is described empirically by the initial mass function.)[11] During the initial collapse, this pre-main-sequence star generates energy through gravitational contraction. Once sufficiently dense, stars begin converting hydrogen into helium and giving off energy through an exothermic nuclear fusion process.[7]

When nuclear fusion of hydrogen becomes the dominant energy production process and the excess energy gained from gravitational contraction has been lost,[12] the star lies along a curve on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram (or HR diagram) called the standard main sequence. Astronomers will sometimes refer to this stage as "zero-age main sequence", or ZAMS.[13][14] The ZAMS curve can be calculated using computer models of stellar properties at the point when stars begin hydrogen fusion. From this point, the brightness and surface temperature of stars typically increase with age.[15]

A star remains near its initial position on the main sequence until a significant amount of hydrogen in the core has been consumed, then begins to evolve into a more luminous star. (On the HR diagram, the evolving star moves up and to the right of the main sequence.) Thus the main sequence represents the primary hydrogen-burning stage of a star's lifetime.[7]

Classification

[edit]

Main sequence stars are divided into the following types:

- O-type main-sequence star

- B-type main-sequence star

- A-type main-sequence star

- F-type main-sequence star

- G-type main-sequence star

- K-type main-sequence star

- M-type main-sequence star

M-type (and, to a lesser extent, K-type)[17] main-sequence stars are usually referred to as red dwarfs.

Properties

[edit]The majority of stars on a typical HR diagram lie along the main-sequence curve. This line is pronounced because both the spectral type and the luminosity depends only on a star's mass, at least to zeroth-order approximation, as long as it is fusing hydrogen at its core—and that is what almost all stars spend most of their "active" lives doing.[18]

The temperature of a star determines its spectral type via its effect on the physical properties of plasma in its photosphere. A star's energy emission as a function of wavelength is influenced by both its temperature and composition. A key indicator of this energy distribution is given by the color index, B − V, which measures the star's magnitude in blue (B) and green-yellow (V) light by means of filters.[note 1] This difference in magnitude provides a measure of a star's temperature.

Dwarf terminology

[edit]Main-sequence stars are called dwarf stars,[19][20] but this terminology is partly historical and can be somewhat confusing. For the cooler stars, dwarfs such as red dwarfs, orange dwarfs, and yellow dwarfs are indeed much smaller and dimmer than other stars of those colors. However, for hotter blue and white stars, the difference in size and brightness between so-called "dwarf" stars that are on the main sequence and so-called "giant" stars that are not, becomes smaller. For the hottest stars the difference is not directly observable and for these stars, the terms "dwarf" and "giant" refer to differences in spectral lines which indicate whether a star is on or off the main sequence. Nevertheless, very hot main-sequence stars are still sometimes called dwarfs, even though they have roughly the same size and brightness as the "giant" stars of that temperature.[21]

The common use of "dwarf" to mean the main sequence is confusing in another way because there are dwarf stars that are not main-sequence stars. For example, a white dwarf is the dead core left over after a star has shed its outer layers, and is much smaller than a main-sequence star, roughly the size of Earth. These represent the final evolutionary stage of many main-sequence stars.[22]

Parameters

[edit]

By treating the star as an idealized energy radiator known as a black body, the luminosity L and radius R can be related to the effective temperature Teff by the Stefan–Boltzmann law:

where σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant. As the position of a star on the HR diagram shows its approximate luminosity, this relation can be used to estimate its radius.[23]

The mass, radius, and luminosity of a star are closely interlinked, and their respective values can be approximated by three relations. First is the Stefan–Boltzmann law, which relates the luminosity L, the radius R and the surface temperature Teff. Second is the mass–luminosity relation, which relates the luminosity L and the mass M. Finally, the relationship between M and R is close to linear. The ratio of M to R increases by a factor of only three over 2.5 orders of magnitude of M. This relation is roughly proportional to the star's inner temperature TI, and its extremely slow increase reflects the fact that the rate of energy generation in the core strongly depends on this temperature, whereas it has to fit the mass-luminosity relation. Thus, a too-high or too-low temperature will result in stellar instability.

A better approximation is to take ε = L/M, the energy generation rate per unit mass, as ε is proportional to TI15, where TI is the core temperature. This is suitable for stars at least as massive as the Sun, exhibiting the CNO cycle, and gives the better fit R ∝ M0.78.[24]

Sample parameters

[edit]The table below shows typical values for stars along the main sequence. The values of luminosity (L), radius (R), and mass (M) are relative to the Sun—a dwarf star with a spectral classification of G2 V. The actual values for a star may vary by as much as 20–30% from the values listed below.[25][why?]

| Stellar class |

Radius, R/R☉ |

Mass, M/M☉ |

Luminosity, L/L☉ |

Temp. (K) |

Examples[27] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O2 | 12 | 100 | 800,000 | 50,000 | BI 253 |

| O6 | 9.8 | 35 | 180,000 | 38,000 | Theta1 Orionis C |

| B0 | 7.4 | 18 | 20,000 | 30,000 | Phi1 Orionis |

| B5 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 800 | 16,400 | Pi Andromedae A |

| A0 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 80 | 10,800 | Alpha Coronae Borealis A |

| A5 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 20 | 8,620 | Beta Pictoris |

| F0 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 6 | 7,240 | Gamma Virginis |

| F5 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 6,540 | Eta Arietis |

| G0 | 1.05 | 1.10 | 1.26 | 5,920 | Beta Comae Berenices |

| G2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5,780 | Sun[note 2] |

| G5 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 5,610 | Alpha Mensae |

| K0 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.40 | 5,240 | 70 Ophiuchi A |

| K5 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.16 | 4,410 | 61 Cygni A[28] |

| M0 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.072 | 3,800 | Lacaille 8760 |

| M5 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.0027 | 3,120 | EZ Aquarii A |

| M8 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.0004 | 2,650 | Van Biesbroeck's star[29] |

| L1 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.00017 | 2,200 | 2MASS J0523−1403 |

Energy generation

[edit]

All main-sequence stars have a core region where energy is generated by nuclear fusion. The temperature and density of this core are at the levels necessary to sustain the energy production that will support the remainder of the star. A reduction of energy production would cause the overlaying mass to compress the core, resulting in an increase in the fusion rate because of higher temperature and pressure. Likewise, an increase in energy production would cause the star to expand, lowering the pressure at the core. Thus the star forms a self-regulating system in hydrostatic equilibrium that is stable over the course of its main-sequence lifetime.[30]

Main-sequence stars employ two types of hydrogen fusion processes, and the rate of energy generation from each type depends on the temperature in the core region. Astronomers divide the main sequence into upper and lower parts, based on which of the two is the dominant fusion process. In the lower main sequence, energy is primarily generated as the result of the proton–proton chain, which directly fuses hydrogen together in a series of stages to produce helium.[31] Stars in the upper main sequence have sufficiently high core temperatures to efficiently use the CNO cycle (see chart). This process uses atoms of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as intermediaries in the process of fusing hydrogen into helium.

At a stellar core temperature of 18 million kelvin, the PP process and CNO cycle are equally efficient, and each type generates half of the star's net luminosity. As this is the core temperature of a star with about 1.5 M☉, the upper main sequence consists of stars above this mass. Thus, roughly speaking, stars of spectral class F or cooler belong to the lower main sequence, while A-type stars or hotter are upper main-sequence stars.[15] The transition in primary energy production from one form to the other spans a range difference of less than a single solar mass. In the Sun, a one solar-mass star, only 1.5% of the energy is generated by the CNO cycle.[32] By contrast, stars with 1.8 M☉ or above generate almost their entire energy output through the CNO cycle.[33]

The observed upper limit for a main-sequence star is 120–200 M☉.[34] The theoretical explanation for this limit is that stars above this mass can not radiate energy fast enough to remain stable, so any additional mass will be ejected in a series of pulsations until the star reaches a stable limit.[35] The lower limit for sustained proton-proton nuclear fusion is about 0.08 M☉ or 80 times the mass of Jupiter.[31] Below this threshold are sub-stellar objects that can not sustain hydrogen fusion, known as brown dwarfs.[36]

Structure

[edit]

Because there is a temperature difference between the core and the surface, or photosphere, energy is transported outward. The two modes for transporting this energy are radiation and convection. A radiation zone, where energy is transported by radiation, is stable against convection and there is very little mixing of the plasma. By contrast, in a convection zone the energy is transported by bulk movement of plasma, with hotter material rising and cooler material descending. Convection is a more efficient mode for carrying energy than radiation, but it will only occur under conditions that create a steep temperature gradient.[30][37]

In massive stars (above 10 M☉)[38] the rate of energy generation by the CNO cycle is very sensitive to temperature, so the fusion is highly concentrated at the core. Consequently, there is a high temperature gradient in the core region, which results in a convection zone for more efficient energy transport.[31] This mixing of material around the core removes the helium ash from the hydrogen-burning region, allowing more of the hydrogen in the star to be consumed during the main-sequence lifetime. The outer regions of a massive star transport energy by radiation, with little or no convection.[30]

Intermediate-mass stars such as Sirius may transport energy primarily by radiation, with a small core convection region.[39] Medium-sized, low-mass stars like the Sun have a core region that is stable against convection, with a convection zone near the surface that mixes the outer layers. This results in a steady buildup of a helium-rich core, surrounded by a hydrogen-rich outer region. By contrast, cool, very low-mass stars (below 0.4 M☉) are convective throughout.[11] Thus the helium produced at the core is distributed across the star, producing a relatively uniform atmosphere and a proportionately longer main-sequence lifespan.[30]

Luminosity-color variation

[edit]

As non-fusing helium accumulates in the core of a main-sequence star, the reduction in the abundance of hydrogen per unit mass results in a gradual lowering of the fusion rate within that mass. Since it is fusion-supplied power that maintains the pressure of the core and supports the higher layers of the star, the core gradually gets compressed. This brings hydrogen-rich material into a shell around the helium-rich core at a depth where the pressure is sufficient for fusion to occur. The high power output from this shell pushes the higher layers of the star further out. This causes a gradual increase in the radius and consequently luminosity of the star over time.[15] For example, the luminosity of the early Sun was only about 70% of its current value.[40] As a star ages it thus changes its position on the HR diagram. This evolution is reflected in a broadening of the main sequence band which contains stars at various evolutionary stages.[41]

Other factors that broaden the main sequence band on the HR diagram include uncertainty in the distance to stars and the presence of unresolved binary stars that can alter the observed stellar parameters. However, even perfect observation would show a fuzzy main sequence because mass is not the only parameter that affects a star's color and luminosity. Variations in chemical composition caused by the initial abundances, the star's evolutionary status,[42] interaction with a close companion,[43] rapid rotation,[44] or a magnetic field can all slightly change a main-sequence star's HR diagram position, to name just a few factors. As an example, there are metal-poor stars (with a very low abundance of elements with higher atomic numbers than helium) that lie just below the main sequence and are known as subdwarfs. These stars are fusing hydrogen in their cores and so they mark the lower edge of the main sequence fuzziness caused by variance in chemical composition.[45]

A nearly vertical region of the HR diagram, known as the instability strip, is occupied by pulsating variable stars known as Cepheid variables. These stars vary in magnitude at regular intervals, giving them a pulsating appearance. The strip intersects the upper part of the main sequence in the region of class A and F stars, which are between one and two solar masses. Pulsating stars in this part of the instability strip intersecting the upper part of the main sequence are called Delta Scuti variables. Main-sequence stars in this region experience only small changes in magnitude, so this variation is difficult to detect.[46] Other classes of unstable main-sequence stars, like Beta Cephei variables, are unrelated to this instability strip.

Lifetime

[edit]

The total amount of energy that a star can generate through nuclear fusion of hydrogen is limited by the amount of hydrogen fuel that can be consumed at the core. For a star in equilibrium, the thermal energy generated at the core must be at least equal to the energy radiated at the surface. Since the luminosity gives the amount of energy radiated per unit time, the total life span can be estimated, to first approximation, as the total energy produced divided by the star's luminosity.[47]

For a star with at least 0.5 M☉, when the hydrogen supply in its core is exhausted and it expands to become a red giant, it can start to fuse helium atoms to form carbon. The energy output of the helium fusion process per unit mass is only about a tenth the energy output of the hydrogen process, and the luminosity of the star increases.[48] This results in a much shorter length of time in this stage compared to the main-sequence lifetime. (For example, the Sun is predicted to spend 130 million years burning helium, compared to about 12 billion years burning hydrogen.)[49] Thus, about 90% of the observed stars above 0.5 M☉ will be on the main sequence.[50] On average, main-sequence stars are known to follow an empirical mass–luminosity relationship.[51] The luminosity (L) of the star is roughly proportional to the total mass (M) as the following power law:

This relationship applies to main-sequence stars in the range 0.1–50 M☉.[52]

The amount of fuel available for nuclear fusion is proportional to the mass of the star. Thus, the lifetime of a star on the main sequence can be estimated by comparing it to solar evolutionary models. The Sun has been a main-sequence star for about 4.5 billion years and it will start to expand rapidly towards a red giant in 6.5 billion years,[53] for a total main-sequence lifetime of roughly 1010 years. Hence:[54]

where M and L are the mass and luminosity of the star, respectively, is a solar mass, is the solar luminosity and is the star's estimated main-sequence lifetime.

Although more massive stars have more fuel to burn and might intuitively be expected to last longer, they also radiate a proportionately greater amount with increased mass. This is required by the stellar equation of state; for a massive star to maintain equilibrium, the outward pressure of radiated energy generated in the core not only must but will rise to match the titanic inward gravitational pressure of its envelope. Thus, the most massive stars may remain on the main sequence for only a few million years, while stars with less than a tenth of a solar mass may last for over a trillion years.[55]

The exact mass-luminosity relationship depends on how efficiently energy can be transported from the core to the surface. A higher opacity has an insulating effect that retains more energy at the core, so the star does not need to produce as much energy to remain in hydrostatic equilibrium. By contrast, a lower opacity means energy escapes more rapidly and the star must burn more fuel to remain in equilibrium.[56] A sufficiently high opacity can result in energy transport via convection, which changes the conditions needed to remain in equilibrium.[15]

In high-mass main-sequence stars, the opacity is dominated by electron scattering, which is nearly constant with increasing temperature. Thus the luminosity only increases as the cube of the star's mass.[48] For stars below 10 M☉, the opacity becomes dependent on temperature, resulting in the luminosity varying approximately as the fourth power of the star's mass.[52] For very low-mass stars, molecules in the atmosphere also contribute to the opacity. Below about 0.5 M☉, the luminosity of the star varies as the mass to the power of 2.3, producing a flattening of the slope on a graph of mass versus luminosity. Even these refinements are only an approximation, however, and the mass-luminosity relation can vary depending on a star's composition.[11]

Evolutionary tracks

[edit]

When a main-sequence star has consumed the hydrogen at its core, the loss of energy generation causes its gravitational collapse to resume and the star evolves off the main sequence. The path which the star follows across the HR diagram is called an evolutionary track.[57] A track known as the zero age main sequence (ZAMS) is where stars of different masses begin their main sequence lives, while a track known as the terminal age main sequence (TAMS) is where stars of different masses end their main sequence lives when hydrogen is depleted in their cores.[58]

Stars with less than 0.23 M☉[59] are predicted to directly become white dwarfs when energy generation by nuclear fusion of hydrogen at their core comes to a halt, but stars in this mass range have main-sequence lifetimes longer than the current age of the universe, so no stars are old enough for this to have occurred.

In stars more massive than 0.23 M☉, the hydrogen surrounding the helium core reaches sufficient temperature and pressure to undergo fusion, forming a hydrogen-burning shell and causing the outer layers of the star to expand and cool. The stage as these stars move away from the main sequence is known as the subgiant branch; it is relatively brief and appears as a gap in the evolutionary track since few stars are observed at that point.

When the helium core of low-mass stars becomes degenerate, or the outer layers of intermediate-mass stars cool sufficiently to become opaque, their hydrogen shells increase in temperature and the stars start to become more luminous. This is known as the red-giant branch; it is a relatively long-lived stage and it appears prominently in H–R diagrams. These stars will eventually end their lives as white dwarfs.[60][61]

The most massive stars do not become red giants; instead, their cores quickly become hot enough to fuse helium and eventually heavier elements and they are known as supergiants. They follow approximately horizontal evolutionary tracks from the main sequence across the top of the H–R diagram. Supergiants are relatively rare and do not show prominently on most H–R diagrams. Their cores will eventually collapse, usually leading to a supernova and leaving behind either a neutron star or black hole.[62]

When a cluster of stars is formed at about the same time, the main-sequence lifespan of these stars will depend on their individual masses. The most massive stars will leave the main sequence first, followed in sequence by stars of ever lower masses. The position where stars in the cluster are leaving the main sequence is known as the turnoff point. By knowing the main-sequence lifespan of stars at this point, it becomes possible to estimate the age of the cluster.[63]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ By measuring the difference between these values, eliminates the need to correct the magnitudes for distance. However, this can be affected by interstellar extinction.

- ^ The Sun is a typical type G2V star.

References

[edit]- ^ Longair, Malcolm S. (2006). The Cosmic Century: A History of Astrophysics and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-521-47436-8.

- ^ a b Brown, Laurie M.; Pais, Abraham; Pippard, A. B., eds. (1995). Twentieth Century Physics. Bristol; New York: Institute of Physics, American Institute of Physics. p. 1696. ISBN 978-0-7503-0310-1. OCLC 33102501.

- ^ a b Russell, H. N. (1913). ""Giant" and "dwarf" stars". The Observatory. 36: 324–329. Bibcode:1913Obs....36..324R.

- ^ Strömgren, Bengt (1933). "On the Interpretation of the Hertzsprung-Russell-Diagram". Zeitschrift für Astrophysik. 7: 222–248. Bibcode:1933ZA......7..222S.

- ^ Schatzman, Evry L.; Praderie, Francoise (1993). The Stars. Springer. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-3-540-54196-7.

- ^ Morgan, W. W.; Keenan, P. C.; Kellman, E. (1943). An atlas of stellar spectra, with an outline of spectral classification. Chicago, Illinois: The University of Chicago press. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ^ a b c Unsöld, Albrecht (1969). The New Cosmos. Springer-Verlag New York Inc. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-387-90886-1.

- ^ Kelly, Patrick L.; et al. (2 April 2018). "Extreme magnification of an individual star at redshift 1.5 by a galaxy-cluster lens". Nature. 2 (4): 334–342. arXiv:1706.10279. Bibcode:2018NatAs...2..334K. doi:10.1038/s41550-018-0430-3. S2CID 125826925.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (2 April 2018). "Rare Cosmic Alignment Reveals Most Distant Star Ever Seen". Space.com. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Gloeckler, George; Geiss, Johannes (2004). "Composition of the local interstellar medium as diagnosed with pickup ions". Advances in Space Research. 34 (1): 53–60. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..34...53G. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2003.02.054.

- ^ a b c Kroupa, Pavel (2002). "The Initial Mass Function of Stars: Evidence for Uniformity in Variable Systems". Science. 295 (5552): 82–91. arXiv:astro-ph/0201098. Bibcode:2002Sci...295...82K. doi:10.1126/science.1067524. PMID 11778039. S2CID 14084249.

- ^ Schilling, Govert (2001). "New Model Shows Sun Was a Hot Young Star". Science. 293 (5538): 2188–2189. doi:10.1126/science.293.5538.2188. PMID 11567116. S2CID 33059330.

- ^ "Zero Age Main Sequence". The SAO Encyclopedia of Astronomy. Swinburne University. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ^ Hansen, Carl J.; Kawaler, Steven D. (1999). Stellar Interiors: Physical Principles, Structure, and Evolution. Astronomy and Astrophysics Library. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-387-94138-7.

- ^ a b c d Clayton, Donald D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10953-4.

- ^ "The Brightest Stars Don't Live Alone". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ Pettersen, B. R.; Hawley, S. L. (1989-06-01). "A spectroscopic survey of red dwarf flare stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 217: 187–200. Bibcode:1989A&A...217..187P. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ^ "Main Sequence Stars". Australia Telescope Outreach and Education. Archived from the original on 2021-11-25.

- ^ Harding E. Smith (21 April 1999). "The Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram". Gene Smith's Astronomy Tutorial. Center for Astrophysics & Space Sciences, University of California, San Diego. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ^ Richard Powell (2006). "The Hertzsprung Russell Diagram". An Atlas of the Universe. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (2006). The Amateur Astronomer. Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-878-7.

- ^ "White Dwarf". COSMOS—The SAO Encyclopedia of Astronomy. Swinburne University. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ "Origin of the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram". University of Nebraska. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ "A course on stars' physical properties, formation and evolution" (PDF). University of St. Andrews. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-02. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ Siess, Lionel (2000). "Computation of Isochrones". Institut d'astronomie et d'astrophysique, Université libre de Bruxelles. Archived from the original on 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2007-12-06.—Compare, for example, the model isochrones generated for a ZAMS of 1.1 solar masses. This is listed in the table as 1.26 times the solar luminosity. At metallicity Z = 0.01 the luminosity is 1.34 times solar luminosity. At metallicity Z = 0.04 the luminosity is 0.89 times the solar luminosity.

- ^ Zombeck, Martin V. (1990). Handbook of Space Astronomy and Astrophysics (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-34787-7. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ "SIMBAD Astronomical Database". Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ^ Luck, R. Earle; Heiter, Ulrike (2005). "Stars within 15 Parsecs: Abundances for a Northern Sample". The Astronomical Journal. 129 (2): 1063–1083. Bibcode:2005AJ....129.1063L. doi:10.1086/427250.

- ^ Staff (1 January 2008). "List of the Nearest Hundred Nearest Star Systems". Research Consortium on Nearby Stars. Archived from the original on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ^ a b c d Brainerd, Jerome James (16 February 2005). "Main-Sequence Stars". The Astrophysics Spectator. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ a b c Karttunen, Hannu (2003). Fundamental Astronomy. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-00179-9.

- ^ Bahcall, John N.; Pinsonneault, M. H.; Basu, Sarbani (2003). "Solar Models: Current Epoch and Time Dependences, Neutrinos, and Helioseismological Properties". The Astrophysical Journal. 555 (2): 990–1012. arXiv:astro-ph/0212331. Bibcode:2001ApJ...555..990B. doi:10.1086/321493. S2CID 13798091.

- ^ Salaris, Maurizio; Cassisi, Santi (2005). Evolution of Stars and Stellar Populations. John Wiley and Sons. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-470-09220-0.

- ^ Oey, M. S.; Clarke, C. J. (2005). "Statistical Confirmation of a Stellar Upper Mass Limit". The Astrophysical Journal. 620 (1): L43 – L46. arXiv:astro-ph/0501135. Bibcode:2005ApJ...620L..43O. doi:10.1086/428396. S2CID 7280299.

- ^ Ziebarth, Kenneth (1970). "On the Upper Mass Limit for Main-Sequence Stars". Astrophysical Journal. 162: 947–962. Bibcode:1970ApJ...162..947Z. doi:10.1086/150726.

- ^ Burrows, Adam; Hubbard, William B.; Saumon, Didier; Lunine, Jonathan I. (1993). "An expanded set of brown dwarf and very low mass star models". Astrophysical Journal. 406 (1): 158–71. Bibcode:1993ApJ...406..158B. doi:10.1086/172427.

- ^ Aller, Lawrence H. (1991). Atoms, Stars, and Nebulae. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31040-6.

- ^ Bressan, A. G.; Chiosi, C.; Bertelli, G. (1981). "Mass loss and overshooting in massive stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 102 (1): 25–30. Bibcode:1981A&A...102...25B.

- ^ Lochner, Jim; Gibb, Meredith; Newman, Phil (6 September 2006). "Stars". NASA. Archived from the original on 2014-11-19. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^ Gough, D. O. (1981). "Solar interior structure and luminosity variations". Solar Physics. 74 (1): 21–34. Bibcode:1981SoPh...74...21G. doi:10.1007/BF00151270. S2CID 120541081.

- ^ Padmanabhan, Thanu (2001). Theoretical Astrophysics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56241-6.

- ^ Wright, J. T. (2004). "Do We Know of Any Maunder Minimum Stars?". The Astronomical Journal. 128 (3): 1273–1278. arXiv:astro-ph/0406338. Bibcode:2004AJ....128.1273W. doi:10.1086/423221. S2CID 118975831.

- ^ Tayler, Roger John (1994). The Stars: Their Structure and Evolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45885-6.

- ^ Sweet, I. P. A.; Roy, A. E. (1953). "The structure of rotating stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 113 (6): 701–715. Bibcode:1953MNRAS.113..701S. doi:10.1093/mnras/113.6.701.

- ^ Burgasser, Adam J.; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Lépine, Sébastien (5–9 July 2004). Spitzer Studies of Ultracool Subdwarfs: Metal-poor Late-type M, L and T Dwarfs. Proceedings of the 13th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems and the Sun. Hamburg, Germany: Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co. p. 237. Bibcode:2005ESASP.560..237B.

- ^ Green, S. F.; Jones, Mark Henry; Burnell, S. Jocelyn (2004). An Introduction to the Sun and Stars. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54622-5.

- ^ Richmond, Michael W. (10 November 2004). "Stellar evolution on the main sequence". Rochester Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ^ a b Prialnik, Dina (2000). An Introduction to the Theory of Stellar Structure and Evolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-65937-6.

- ^ Schröder, K.-P.; Connon Smith, Robert (May 2008). "Distant future of the Sun and Earth revisited". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 386 (1): 155–163. arXiv:0801.4031. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.386..155S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13022.x. S2CID 10073988.

- ^ Arnett, David (1996). Supernovae and Nucleosynthesis: An Investigation of the History of Matter, from the Big Bang to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01147-9.—Hydrogen fusion produces 8×1014 J/kg while helium fusion produces 8×1013 J/kg.

- ^ For a detailed historical reconstruction of the theoretical derivation of this relationship by Eddington in 1924, see: Lecchini, Stefano (2007). How Dwarfs Became Giants. The Discovery of the Mass-Luminosity Relation. Bern Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science. ISBN 978-3-9522882-6-9.

- ^ a b Rolfs, Claus E.; Rodney, William S. (1988). Cauldrons in the Cosmos: Nuclear Astrophysics. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-72457-7.

- ^ Sackmann, I.-Juliana; Boothroyd, Arnold I.; Kraemer, Kathleen E. (November 1993). "Our Sun. III. Present and Future". Astrophysical Journal. 418: 457–468. Bibcode:1993ApJ...418..457S. doi:10.1086/173407.

- ^ Hansen, Carl J.; Kawaler, Steven D. (1994). Stellar Interiors: Physical Principles, Structure, and Evolution. Birkhäuser. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-387-94138-7.

- ^ Laughlin, Gregory; Bodenheimer, Peter; Adams, Fred C. (1997). "The End of the Main Sequence". The Astrophysical Journal. 482 (1): 420–432. Bibcode:1997ApJ...482..420L. doi:10.1086/304125.

- ^ Imamura, James N. (7 February 1995). "Mass-Luminosity Relationship". University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 14 December 2006. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- ^ Icko Iben (29 November 2012). Stellar Evolution Physics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1481–. ISBN 978-1-107-01657-6.

- ^ Martins, F.; Palacios, A. (January 2021). "Spectroscopic evolution of massive stars near the main sequence at low metallicity". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 645. id. A67. arXiv:2010.13430. Bibcode:2021A&A...645A..67M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039337.

- ^ Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory (April 1997). "A Dying Universe: The Long Term Fate and Evolution of Astrophysical Objects". Reviews of Modern Physics. 69 (2): 337–372. arXiv:astro-ph/9701131. Bibcode:1997RvMP...69..337A. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.69.337. S2CID 12173790.

- ^ Staff (12 October 2006). "Post-Main Sequence Stars". Australia Telescope Outreach and Education. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- ^ Girardi, L.; Bressan, A.; Bertelli, G.; Chiosi, C. (2000). "Evolutionary tracks and isochrones for low- and intermediate-mass stars: From 0.15 to 7 Msun, and from Z=0.0004 to 0.03". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement. 141 (3): 371–383. arXiv:astro-ph/9910164. Bibcode:2000A&AS..141..371G. doi:10.1051/aas:2000126. S2CID 14566232.

- ^ Sitko, Michael L. (24 March 2000). "Stellar Structure and Evolution". University of Cincinnati. Archived from the original on 26 March 2005. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^ Krauss, Lawrence M.; Chaboyer, Brian (2003). "Age Estimates of Globular Clusters in the Milky Way: Constraints on Cosmology". Science. 299 (5603): 65–69. Bibcode:2003Sci...299...65K. doi:10.1126/science.1075631. PMID 12511641. S2CID 10814581.

Further reading

[edit]General

[edit]- Kippenhahn, Rudolf, 100 Billion Suns, Basic Books, New York, 1983.

Technical

[edit]- Arnett, David (1996). Supernovae and Nucleosynthesis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Bahcall, John N. (1989). Neutrino Astrophysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37975-5.

- Bahcall, John N.; Pinsonneault, M.H.; Basu, Sarbani (2001). "Solar Models: Current Epoch and Time Dependences, Neutrinos, and Helioseismological Properties". The Astrophysical Journal. 555 (2): 990–1012. arXiv:astro-ph/0010346. Bibcode:2001ApJ...555..990B. doi:10.1086/321493. S2CID 13798091.

- Barnes, C. A.; Clayton, D. D.; Schramm, D. N., eds. (1982). Essays in Nuclear Astrophysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bowers, Richard L.; Deeming, Terry (1984). Astrophysics I: Stars. Boston: Jones and Bartlett.

- Carroll, Bradley W. & Ostlie, Dale A. (2007). An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics. San Francisco: Pearson Education Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-8053-0402-2.

- Chabrier, Gilles; Baraffe, Isabelle (2000). "Theory of Low-Mass Stars and Substellar Objects". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 38: 337–377. arXiv:astro-ph/0006383. Bibcode:2000ARA&A..38..337C. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.38.1.337. S2CID 59325115.

- Chandrasekhar, S. (1967). An Introduction to the study of stellar Structure. New York: Dover. Bibcode:1967aits.book.....C.

- Clayton, Donald D. (1983). Principles of Stellar Evolution and Nucleosynthesis. Chicago: University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-10952-7.

- Cox, J. P.; Giuli, R. T. (1968). Principles of Stellar Structure. New York City: Gordon and Breach. Bibcode:1968pss..book.....C.

- Fowler, William A.; Caughlan, Georgeanne R.; Zimmerman, Barbara A. (1967). "Thermonuclear Reaction Rates, I". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 5: 525. Bibcode:1967ARA&A...5..525F. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.05.090167.002521.

- Fowler, William A.; Caughlan, Georgeanne R.; Zimmerman, Barbara A. (1975). "Thermonuclear Reaction Rates, II". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 13: 69. Bibcode:1975ARA&A..13...69F. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.13.090175.000441.

- Hansen, Carl J.; Kawaler, Steven D.; Trimble, Virginia (2004). Stellar Interiors: Physical Principles, Structure, and Evolution, Second Edition. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Harris, Michael J.; Fowler, William A.; Caughlan, Georgeanne R.; Zimmerman, Barbara A. (1983). "Thermonuclear Reaction Rates, III". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 21: 165. Bibcode:1983ARA&A..21..165H. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.21.090183.001121.

- Iben, Icko Jr (1967). "Stellar Evolution Within and Off the Main Sequence". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 5: 571. Bibcode:1967ARA&A...5..571I. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.05.090167.003035.

- Iglesias, Carlos A.; Rogers, Forrest J. (1996). "Updated Opal Opacities". The Astrophysical Journal. 464: 943. Bibcode:1996ApJ...464..943I. doi:10.1086/177381.

- Kippenhahn, Rudolf; Weigert, Alfred (1990). Stellar Structure and Evolution. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Liebert, James; Probst, Ronald G. (1987). "Very Low Mass Stars". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 25: 437. Bibcode:1987ARA&A..25..473L. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.25.090187.002353.

- Novotny, Eva (1973). Introduction to Stellar Atmospheres and Interior. New York City: Oxford University Press.

- Padmanabhan, T. (2002). Theoretical Astrophysics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Prialnik, Dina (2000). An Introduction to the Theory of Stellar Structure and Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bibcode:2000itss.book.....P.

- Shore, Steven N. (2003). The Tapestry of Modern Astrophysics. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons.

Main sequence

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Overview

Definition

The main sequence refers to a phase in the evolution of stars during which they achieve and maintain hydrostatic equilibrium, with their internal structure and energy output powered primarily by nuclear fusion reactions converting hydrogen into helium in their cores. This stable configuration allows stars to radiate energy at a nearly constant rate for an extended period, defining the primary adulthood of a star's life cycle.[8][10][11] Stars spend the vast majority of their lifetimes—approximately 90%—on the main sequence, with the duration varying inversely with stellar mass: more massive stars evolve more rapidly through this phase due to higher fusion rates, while lower-mass stars like the Sun persist for billions of years. This phase begins once core temperatures reach about 10 million Kelvin, igniting the proton-proton chain or CNO cycle for hydrogen fusion, and ends when sufficient helium has accumulated in the core to halt further hydrogen burning.[12][13] In contrast to pre-main sequence protostars, which contract gravitationally without sustained core fusion and appear larger and cooler on observational diagrams, main sequence stars are compact and follow a well-defined luminosity-temperature relation. Following the main sequence, stars with initial masses above about 0.4 solar masses leave this phase to expand into red giants or supergiants as shell fusion dominates, marking the onset of more dynamic evolutionary stages.[14][15] Main sequence stars constitute the overwhelming majority of stars in stellar populations across galaxies, comprising around 90% of all observed stars, which underscores their fundamental role in galactic structure and chemical enrichment through ongoing nucleosynthesis. The term "main sequence" derives from the continuous, diagonal band these stars form on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, reflecting their shared physical properties.[1][16]Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram

The Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) diagram serves as the primary observational tool for classifying stars based on their intrinsic properties, plotting stellar luminosity against effective temperature to reveal fundamental patterns in stellar populations.[17] The vertical axis represents luminosity on a logarithmic scale, spanning several orders of magnitude from the faintest dwarfs to the most luminous supergiants, while the horizontal axis denotes effective temperature, typically ranging from about 50,000 K to 3,000 K and decreasing from left to right to align hotter stars on the left side.[2] This arrangement allows for a clear visualization of the relationships between a star's energy output and surface conditions, with the logarithmic scaling on both axes accommodating the vast dynamic range observed in stellar data.[2] A prominent feature of the HR diagram is the main sequence, a nearly diagonal band that occupies the central region and accounts for the majority of stars in any given sample.[17] This band extends from the upper left, where hot, luminous O-type stars with temperatures exceeding 30,000 K and luminosities thousands of times that of the Sun reside, to the lower right, encompassing cool, dim M-type dwarfs with temperatures around 3,000 K and luminosities a fraction of solar.[2] Stars along this sequence represent hydrogen-fusing objects in hydrostatic equilibrium, forming the backbone of stellar classification.[18] The HR diagram's structure is empirically derived from observations of open and globular star clusters, where stars share a common distance—allowing conversion of apparent magnitudes to absolute luminosities—and approximate coeval formation, minimizing scatter due to age variations.[19] By plotting cluster members, astronomers construct clean diagrams that highlight the main sequence as a coherent locus, free from the dispersion seen in field star samples affected by differing distances and evolutionary stages.[20] The zero-age main sequence (ZAMS) marks the initial locus on the HR diagram where newly formed stars first arrive after protostellar contraction, igniting core hydrogen fusion and settling into stable main-sequence positions.[21] For stars of initial masses between approximately 0.08 and 150 solar masses, the ZAMS traces the starting point of this phase, with higher-mass stars positioned toward the hot, luminous end and lower-mass ones toward the cool, faint end, reflecting their mass-dependent luminosities and temperatures at birth.[21] This boundary provides a reference for modeling early stellar evolution and interpreting cluster diagrams.[21]Historical Development

Early Observations

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, astronomers began systematically classifying stellar spectra to identify patterns in stellar properties. At the Harvard College Observatory, Edward C. Pickering initiated spectral classification efforts in the 1880s, which were advanced by Annie Jump Cannon, who refined the system into the iconic O-B-A-F-G-K-M sequence based on absorption line characteristics indicative of surface temperature. This sequence formed the backbone of the Henry Draper Catalogue, a comprehensive nine-volume work published between 1918 and 1924 that classified the spectra of over 225,000 stars, enabling the first large-scale analysis of stellar types.[22] Simultaneously, observations of open star clusters such as the Pleiades and Hyades revealed intriguing correlations between a star's spectral type and its brightness. These nearby clusters, with their shared distances, allowed astronomers to compare apparent magnitudes directly as proxies for intrinsic brightness, showing that hotter (earlier spectral type) stars tended to be brighter than cooler ones within the same group. Such patterns emerged from photographic surveys in the early 1900s, highlighting systematic relationships that deviated from random distributions.[23] Danish astronomer Ejnar Hertzsprung pioneered the visualization of these trends in his 1905 paper, where he analyzed photographic magnitudes and spectra to distinguish intrinsically bright "giant" stars from fainter "dwarfs" of similar spectral types. Building on cluster data, Hertzsprung published plots in 1911 of absolute magnitudes against spectral types for stars in the Pleiades and Hyades, revealing a diagonal sequence of stars aligning from hot, luminous to cool, dim, which hinted at a fundamental stellar progression.[24] Independently, American astronomer Henry Norris Russell developed similar insights around the same time. In 1913, Russell presented diagrams plotting absolute magnitudes versus spectral classes for a broad sample of stars, including cluster members, confirming the sequence observed by Hertzsprung and emphasizing its prevalence among most stars. These early plots, collectively known as the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, marked a pivotal empirical foundation for understanding stellar distributions.[25]Theoretical Foundations

In the 1920s, Arthur Eddington laid the groundwork for understanding the main sequence through theoretical models of stellar interiors, emphasizing hydrostatic equilibrium—the balance between gravitational contraction and internal pressure—and radiative energy transport. These models demonstrated that a star's mass determines its luminosity and effective temperature, explaining why observed stars cluster along a band in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram as objects in stable, homologous configurations. Eddington's derivation of the mass-luminosity relation, assuming ideal gas pressure and radiative opacity, provided the first quantitative link between these parameters, interpreting the sequence as a phase of equilibrium sustained by nuclear energy sources yet to be fully identified.[26][27] Building on this framework in the 1930s, Hans Bethe revolutionized the field with his work in nuclear astrophysics, identifying the proton-proton (pp) chain and the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (CNO) cycle as the dominant mechanisms for hydrogen fusion into helium in stellar cores. For lower-mass stars like the Sun, the pp chain dominates, while the more temperature-sensitive CNO cycle prevails in more massive stars, both releasing energy that counters gravitational collapse and maintains the hydrostatic stability central to Eddington's models. Bethe's calculations showed these reactions produce the luminosity observed in main-sequence stars, resolving the long-standing energy problem and confirming the sequence as a prolonged phase of core hydrogen burning.[28] The 1950s brought significant refinements through early computer-based models that incorporated realistic opacity laws—accounting for photon absorption and scattering—and convective energy transport in stellar envelopes, enhancing the accuracy of main-sequence predictions. Researchers like Louis Henyey developed numerical integration techniques to solve the coupled equations of stellar structure, enabling simulations that verified the stability of hydrogen-burning stars over billions of years and better matched observational data from clusters. These advancements highlighted how convection in lower main-sequence stars and radiative transfer in upper-mass ones regulate internal conditions, solidifying the theoretical basis for the sequence's longevity.[29] Emerging from these computational efforts, the zero-age main sequence (ZAMS) concept describes the initial theoretical track where newly formed stars of different masses settle into hydrogen-fusion equilibrium, marking the onset of their main-sequence phase. Pioneered in evolutionary models by Allan Sandage, the ZAMS locus in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram represents chemically homogeneous stars just achieving full thermal balance, providing a benchmark for interpreting cluster ages and evolutionary paths. This framework underscored the main sequence not as a static line but as the starting point for gradual core evolution driven by fuel consumption.[30]Classification

Spectral Classification

The Morgan-Keenan (MK) spectral classification system categorizes main-sequence stars primarily based on the appearance and strength of absorption lines in their spectra, which reflect the ionization states and chemical composition at their surface temperatures.[31] The system uses the sequence O, B, A, F, G, K, M, ordered from hottest to coolest, with O-type stars exhibiting temperatures exceeding 30,000 K and appearing blue, while M-type stars have temperatures below 3,700 K and appear red.[32] This classification arises from the dominance of different spectral features: O stars show strong lines from ionized helium (He II) due to high temperatures, B stars feature neutral helium (He I), A stars display prominent hydrogen Balmer lines, F stars have enhanced ionized metals, G stars like the Sun exhibit neutral metals and weaker hydrogen lines, K stars show strong neutral metals and molecular bands, and M stars are marked by titanium oxide (TiO) bands and abundant metal lines.[33] Each spectral type is subdivided into 10 numerical subtypes from 0 (hottest) to 9 (coolest within the class), providing finer resolution of temperature; for example, the Sun is classified as G2V, indicating a G-type star with subtype 2 and luminosity class V for main-sequence stars.[31] For main-sequence stars (luminosity class V), the line strengths and ionization states directly correlate with effective surface temperatures, typically ranging from over 50,000 K for O0 to around 2,500 K for late M subtypes, without significant broadening from luminosity effects seen in giants.[32] Approximate temperature ranges for the primary classes are: O (30,000–60,000 K), B (10,000–30,000 K), A (7,500–10,000 K), F (6,000–7,500 K), G (5,200–6,000 K), K (3,700–5,200 K), and M (2,400–3,700 K).[32] The MK system has been extended to cooler objects beyond M types, with L, T, and Y spectral classes representing the continuation of the main sequence for very low-mass stars and substellar objects.[34] L dwarfs, defined by the disappearance of TiO and VO bands in favor of metal hydrides and alkali lines, span temperatures from about 1,300–2,500 K and include some hydrogen-fusing low-mass main-sequence stars.[35] T dwarfs, characterized by methane (CH₄) absorption in the near-infrared, have temperatures of 700–1,300 K and mark the transition to substellar objects, while Y dwarfs, with ammonia (NH₃) features and temperatures below 500 K, extend the sequence further into planetary-mass regimes.[34][36] These extensions maintain the temperature-based progression of the original system, focusing on molecular and atomic signatures in cooler atmospheres.[34]Dwarf Terminology

In the Morgan-Keenan (MK) classification system, introduced in 1943, stars are assigned luminosity classes using Roman numerals from I to V based on the widths and profiles of absorption lines in their spectra, which indicate surface gravity and thus luminosity for a given temperature. Class I denotes supergiants, the most luminous and lowest-gravity stars; class II represents bright giants; class III indicates normal giants; class IV designates subgiants; and class V corresponds to dwarfs, which are the main-sequence stars undergoing stable hydrogen fusion in their cores. This system builds on spectral classification by adding a luminosity dimension, allowing precise categorization of stars' evolutionary positions.[37][38] The term "dwarf" for luminosity class V stars was formalized in the MK system to distinguish these "normal" stars from the more luminous giants and supergiants, reflecting their position along the main sequence on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram as identified in earlier work. Main-sequence dwarfs constitute the majority of stars in the galaxy and are characterized by spectra showing narrower lines due to higher surface gravity compared to evolved giants. Extensions to the system include class VI for subdwarfs and class VII (or D) for white dwarfs, though the latter are not true main-sequence objects.[37][39] Subdwarfs, assigned luminosity class VI, are metal-poor variants of main-sequence stars with reduced heavy-element abundances relative to solar values, leading to slightly hotter and bluer appearances for their temperatures; they are commonly found in old populations such as globular clusters. Examples include stars like Kapteyn's Star, classified as sdM1, which exhibit weakened metal lines in their spectra. The use of "dwarf" in this terminology does not imply small physical size—main-sequence stars range from compact red dwarfs to expansive O-type stars—but rather highlights their greater average density and unevolved status as core hydrogen-burning objects, in contrast to the low-density, expanded envelopes of giants. This naming avoids confusion with white dwarfs, which are a distinct post-main-sequence endpoint.[40][39]Physical Properties

Key Parameters

The mass of a main-sequence star is its most fundamental parameter, spanning a range from approximately 0.08 to 150 solar masses (M⊙), with the lower limit set by the onset of hydrogen fusion and the upper by instabilities in massive stars.[41] This mass primarily determines the star's evolutionary path, internal structure, and observable properties during the main-sequence phase, as higher masses lead to greater central pressures and temperatures that drive more intense nuclear fusion.[42] The radius of main-sequence stars varies from about 0.1 to roughly 10 solar radii (R⊙), with low-mass stars being compact and high-mass stars more extended due to increased internal support from radiation pressure.[43] Effective temperature, which defines the star's spectral type, ranges from 3,000 K for cool M-type dwarfs to 50,000 K for hot O-type stars, influencing the ionization states in their atmospheres.[44][45] Luminosity, the total energy output from core hydrogen fusion, spans from 10^{-4} to 10^6 solar luminosities (L⊙), with the vast range reflecting the sensitivity of fusion rates to mass.[46] Secondary parameters include surface gravity, typically expressed as log g values from about 3.5 to 5.0 (in cm/s²), which decreases with increasing radius for a given mass and affects spectral line broadening.[47] Rotation rates vary widely, with equatorial velocities often ranging from a few km/s in older, low-mass stars like the Sun to over 200 km/s in young, massive stars, influencing angular momentum transport and magnetic activity.[48]Parameter Relations

The mass-luminosity relation describes how the luminosity of a main-sequence star scales with its mass , a fundamental connection arising from the balance of nuclear energy generation and gravitational structure. For low-mass main-sequence stars (typically ), the relation is empirically approximated as , reflecting the increasing efficiency of hydrogen fusion as core temperatures rise with mass. This scaling is derived from stellar structure models using homology principles, where the virial theorem links gravitational potential energy to thermal energy, and hydrostatic equilibrium requires higher central pressures and temperatures for more massive stars; these in turn boost the nuclear reaction rates (primarily the pp-chain or CNO cycle) that power luminosity, with the exponent emerging from opacity and energy transport assumptions in radiative zones. For high-mass stars (), the relation flattens to , as radiation pressure from electron scattering opacity begins to support much of the stellar envelope against gravity, limiting further luminosity increases per unit mass and approaching the Eddington limit. This theoretical framework was first outlined by Eddington, who used radiative transfer and thermodynamic arguments to predict (where is the mean molecular weight and is opacity), later refined with observations from eclipsing binaries to confirm the piecewise exponents.[49][50][51] The luminosity of a main-sequence star is also tied to its radius and effective surface temperature through the Stefan-Boltzmann law, which states that the total radiated power is , where is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant. This relation applies to stars modeled as blackbody radiators, allowing derivation of one parameter from the others; for instance, hotter or larger stars emit proportionally more energy, explaining the main-sequence trend from cool, dim dwarfs to hot, bright giants in mass terms. In practice, main-sequence stars' effective temperatures range from about 2500 K for low-mass M dwarfs to over 30,000 K for O-type stars, with radii scaling to maintain the observed luminosity-mass correlation.[52] A complementary mass-radius relation for low-mass main-sequence stars approximates , indicating that radius grows sublinearly with mass due to the increasing dominance of ideal gas pressure over degeneracy in higher-mass objects. This empirical fit stems from detailed evolutionary models incorporating equation-of-state variations across the hydrogen-burning core and convective envelopes. For higher masses, the exponent decreases slightly as radiation pressure expands the envelope. Metallicity, the abundance of elements heavier than helium, introduces slight shifts in these relations, particularly for low-mass stars where opacity from metal lines affects energy transport and thus equilibrium structure. Lower-metallicity stars tend to be slightly more luminous and hotter at fixed mass due to reduced blanketing and enhanced nuclear efficiency, altering the mass-luminosity slope by up to 10-15% in the lower main sequence; these effects are quantified in models calibrated to spectroscopic data.[53][10]Nuclear Processes

Energy Generation Mechanisms

Main sequence stars generate energy through nuclear fusion in their cores, primarily converting hydrogen into helium via thermonuclear reactions. This process releases energy according to Einstein's mass-energy equivalence, , where a small fraction of the reactants' mass is converted into electromagnetic radiation and kinetic energy carried away by particles.[54] The ignition of hydrogen burning requires core temperatures exceeding K, at which point the Coulomb barrier between protons is overcome, allowing fusion to proceed efficiently.[55] The dominant energy generation mechanism varies with stellar mass, with lower-mass stars relying on the proton-proton (p-p) chain and higher-mass stars on the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (CNO) cycle. In both cases, the net reaction is the fusion of four protons into one helium-4 nucleus, releasing approximately 26.7 MeV of energy per reaction, equivalent to about 0.7% of the initial mass being converted to energy due to the mass defect between reactants and products.[54] This energy primarily emerges as photons, though neutrinos—nearly massless particles that interact weakly with matter—carry away roughly 2% of the total output, escaping the star directly.[56] The proton-proton chain, first detailed by Hans Bethe and Charles Critchfield, dominates in stars with masses below approximately 1.5 solar masses (), such as the Sun. It proceeds in three main branches, but the primary branch accounts for most reactions under typical conditions. The initial step involves the weak interaction overcoming the Pauli exclusion principle: two protons fuse to form a deuterium nucleus, a positron, and an electron neutrino: The deuterium then captures another proton to produce helium-3 and a gamma ray: Finally, two helium-3 nuclei combine to yield helium-4 and two protons: The overall process recycles two protons, achieving the net transformation , with the energy distributed as kinetic energy of particles and photons.[57] This chain is temperature-sensitive, with rates increasing slowly due to the bottleneck in the first step.[58] In contrast, the CNO cycle, proposed by Bethe, prevails in stars above about 1.5 , where higher core temperatures accelerate the reactions. It uses carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen isotopes as catalysts to facilitate proton captures, without net consumption of these elements. The cycle begins with carbon-12 capturing a proton to form nitrogen-13, which decays via positron emission: ^{12}\mathrm{C} + p \rightarrow ^{13}\mathrm{N} + \gamma, \quad ^{13}\mathrm{N} \rightarrow ^{13}\mathrm{C} + e^+ + \nu_e Subsequent steps involve further proton captures and beta decays through nitrogen-13, carbon-13, nitrogen-14, oxygen-15, and nitrogen-15, culminating in: This closes the cycle, regenerating the initial carbon-12 while producing the same net helium synthesis as the p-p chain: .[59] The CNO process is far more temperature-dependent than the p-p chain, making it efficient in hotter cores of massive stars.[60]Mass-Dependent Variations

Stars of low mass, below approximately 0.35 solar masses (M⊙), are fully convective throughout their interiors during the main sequence phase, relying exclusively on the proton-proton (pp) chain for hydrogen fusion into helium.[61] This process generates energy at a low rate, resulting in correspondingly low luminosities that place these stars, often M dwarfs, at the faint end of the main sequence.[62] For intermediate-mass stars in the range of approximately 0.35 to 1.2 M⊙, the cores are radiative, with the pp chain remaining the dominant energy source, though the contribution from the carbon-nitrogen-oxygen (CNO) cycle begins to increase toward the upper end of this range.[63] The CNO cycle becomes comparable to the pp chain around 1.2 M⊙, after which the CNO fraction rises significantly.[63] In higher-mass stars above 1.2 M⊙, the cores are convective due to the intense, centralized energy generation from the increasingly dominant CNO cycle, with this effect prominent in stars exceeding 1.5 M⊙ where CNO drives rapid evolution along the main sequence.[64] [63] This shift arises from the CNO cycle's strong temperature dependence, which concentrates fusion in a compact, hot core region.[65] Across the main sequence, energy generation efficiency escalates with increasing stellar mass, primarily because higher masses yield hotter cores that accelerate fusion rates. The nuclear energy production rate ε scales approximately as ε ∝ ρ T^ν, where ρ is density, T is temperature, and the effective power-law exponent ν reaches 15–18 for the pp chain at elevated temperatures relevant to more massive stars.[66] For the CNO cycle, ν is similarly high (around 18–20), amplifying the mass-luminosity relation in upper main sequence stars.[66]Internal Structure

Core Region

The core region of main sequence stars constitutes the central zone where nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium occurs, powering the star's luminosity. This region extends from the center outward to typically 20-25% of the star's total radius for solar-type stars, varying with mass (smaller fractional radius in more massive stars), and consists of a fully ionized plasma dominated by hydrogen and helium.[67] Extreme physical conditions prevail in the core to facilitate sustained fusion reactions. Central temperatures typically range from 10 to 40 million Kelvin, increasing with stellar mass, while densities span ~1 to ~10^3 g/cm³, with lower-mass stars exhibiting higher central densities due to their more compact structures.[68][69] For example, the Sun's core reaches about 15 million K and 150 g/cm³.[67] The core's composition undergoes significant evolution during the main sequence phase. Initially, the plasma has a hydrogen mass fraction of roughly 70%, with helium comprising most of the remainder, reflecting primordial abundances. As hydrogen fuses into helium, the central hydrogen fraction depletes to approximately 35% by the end of this phase, enriching the core in helium.[70][71] Hydrostatic equilibrium governs the core's stability, ensuring that the inward pull of gravity is counterbalanced by the outward pressure gradient. This fundamental relation is expressed as where is the pressure, the radial distance from the center, the gravitational constant, the mass enclosed within radius , and the local density.[72]Envelope and Zones

The envelope of a main sequence star encompasses the outer layers beyond the core, where energy generated from nuclear fusion is transported to the surface primarily through radiative diffusion and convection. These zones play a crucial role in determining the star's thermal structure and luminosity, with the specific configuration depending on the star's mass and composition.[62] In the radiative zone, energy is carried outward by the diffusion of photons, which repeatedly scatter off particles due to opacity, resulting in a slow migration that can take up to a million years for photons to traverse the zone. This mechanism dominates the envelopes of high-mass main sequence stars, where high temperatures and ionization states favor radiative transfer over convection.[62][66] The convective zone, in contrast, transports energy through the bulk motion of plasma in convection cells, where hotter material rises and cooler material sinks, enabling efficient mixing of elements and heat. This zone is deep and extends throughout much of low-mass main sequence stars, including fully convective M dwarfs with masses below approximately 0.35 solar masses, while it remains shallow near the surface in high-mass stars.[62][73] At the outermost boundary lies the photosphere, the visible "surface" of the star, which is approximately 100–500 km thick and defined by the layer where the optical depth reaches about 2/3, allowing photons to escape freely and form the observed spectrum.[74][75] Opacity in these envelope zones, which governs photon scattering and absorption, varies with temperature and composition: in cooler main sequence stars, the dominant source is the H⁻ ion formed by electron attachment to neutral hydrogen, while in hotter stars, electron scattering via Thomson scattering prevails due to full ionization.[66]Observational Characteristics

Luminosity-Color Relation

The luminosity-color relation describes the empirical correlation observed among main sequence stars between their absolute luminosity (or magnitude) and color, as proxied by the B-V color index, forming a diagonal band in the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram where hotter, bluer stars exhibit higher luminosities than cooler, redder ones. This relation arises from the interplay of stellar mass, effective temperature, and radius, with higher-mass stars being both hotter and more luminous. For main sequence stars, the B-V color index ranges from approximately -0.3 for hot O-type stars, which appear blue due to their high temperatures exceeding 30,000 K, to +1.5 for cool M-type stars, which are redder with temperatures around 3,000 K.[76] The main sequence band exhibits an intrinsic width of roughly 0.2 magnitudes in color or magnitude at fixed parameters, reflecting natural scatter introduced by differences in stellar age, metallicity, and rotation. Younger stars or those with higher metallicity may appear slightly brighter or shifted in color due to enhanced opacity or mixing processes, while rapid rotation can distort stellar shapes and alter surface temperatures, broadening the sequence. This scatter is minimized in homogeneous populations but becomes evident in field stars or diverse clusters.[77] Observationally, the relation is robustly demonstrated through color-magnitude diagrams of open clusters, such as the intermediate-age cluster M67 (NGC 2682), where the main sequence forms a well-defined locus spanning a wide range in color and luminosity, allowing precise fitting and age determination with scatters consistent with evolutionary effects.[78] Data from the Gaia mission, especially following the 2018 Data Release 2, Data Release 3 in 2022, and subsequent releases as of 2025, have refined this relation for nearby stars by providing unprecedented astrometric and photometric precision, enabling tighter calibrations of the main sequence band with reduced distance uncertainties and revealing subtler intrinsic variations in color-luminosity correlations across the Galactic disk.[79]Sample Parameters

The main sequence encompasses a wide range of stellar masses, from low-mass red dwarfs to high-mass blue dwarfs, each exhibiting distinct physical parameters that reflect their spectral types and evolutionary positions. Representative examples across this spectrum illustrate the diversity in mass, radius, effective temperature, and luminosity, drawn from well-studied stars and theoretical models calibrated to observations. These parameters are normalized to solar units for clarity, highlighting how lower-mass stars are cooler and dimmer, while higher-mass ones are hotter and more luminous. A canonical example is the Sun, a G2V main-sequence star with a mass of 1 M⊙, radius of 1 R⊙, effective temperature of 5772 K, and luminosity of 1 L⊙.[80] At the low-mass end, Proxima Centauri, an M5.5V red dwarf, has a mass of 0.122 M⊙, radius of 0.154 R⊙, effective temperature of 3050 K, and luminosity of 0.0015 L⊙, making it one of the faintest and coolest main-sequence stars observable. For high-mass representatives, theoretical models of a 20 M⊙ O-type main-sequence star yield a radius of approximately 10 R⊙, effective temperature around 37,000 K, and luminosity of about 1.2 × 10^5 L⊙, consistent with parameters for early-type stars like those in young clusters.[81] Such stars power intense radiation and short main-sequence lifetimes, contrasting with solar-type examples.| Star | Spectral Type | Mass (M⊙) | Radius (R⊙) | Effective Temperature (K) | Luminosity (L⊙) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | G2V | 1 | 1 | 5772 | 1 |

| Proxima Centauri | M5.5V | 0.122 | 0.154 | 3050 | 0.0015 |

| 20 M⊙ model | O-type | 20 | ~10 | ~37,000 | ~1.2 × 10^5 |

![{\displaystyle \tau _{\text{MS}}\approx 10^{10}{\text{years}}\left[{\frac {M}{M_{\bigodot }}}\right]\left[{\frac {L_{\bigodot }}{L}}\right]=10^{10}{\text{years}}\left[{\frac {M}{M_{\bigodot }}}\right]^{-2.5}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3712d23010eb29f6e900c55e7101048e76a4651d)