Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Haemophilus

View on Wikipedia

| Haemophilus | |

|---|---|

| |

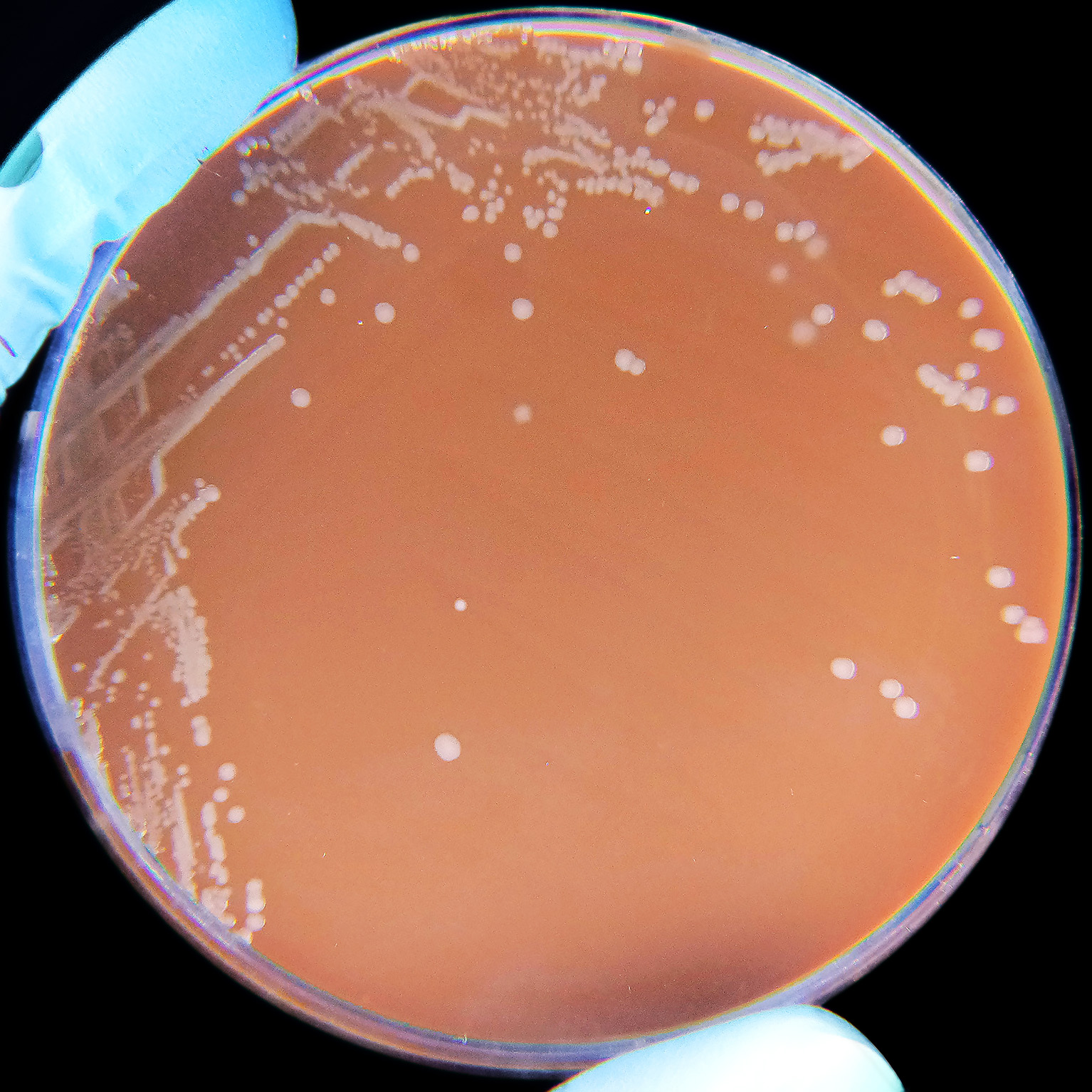

| Haemophilus influenzae on a Chocolate agar plate. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Pseudomonadati |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Pasteurellales |

| Family: | Pasteurellaceae |

| Genus: | Haemophilus Winslow et al. 1917 |

| Species | |

|

H. aegyptius | |

Haemophilus is a genus of Gram-negative, pleomorphic, coccobacilli bacteria belonging to the family Pasteurellaceae.[2][3] While Haemophilus bacteria are typically small coccobacilli, they are categorized as pleomorphic bacteria because of the wide range of shapes they occasionally assume. These organisms inhabit the mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract, mouth, vagina, and intestinal tract.[4] The genus includes commensal organisms along with some significant pathogenic species such as H. influenzae—a cause of sepsis and bacterial meningitis in young children—and H. ducreyi, the causative agent of chancroid. All members are either aerobic or facultatively anaerobic. This genus has been found to be part of the salivary microbiome.[5]

Metabolism

[edit]Most members of the genus Haemophilus require at least one of these blood factors for growth: hemin (sometimes called 'X-factor') and/or nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD; sometimes called 'V-factor'); they usually will not grow on blood agar plates. While NAD is released into blood agar by red blood cells, hemin is bound to the blood cells and is unavailable to bacteria in this medium which prevents the growth of many Haemophilus species.[6] They are unable to synthesize important parts of the cytochrome system needed for respiration, and they obtain these substances from the heme fraction of blood hemoglobin. Clinical laboratories use tests for the hemin and NAD requirement to identify the isolates as Haemophilus species.[4] The species Haemophilus haemoglobinophilus is an exception to this, as it has been shown to grow well on both blood and chocolate agars.[7][self-published source?]

Chocolate agar is an excellent Haemophilus growth medium, as it allows for increased accessibility to these factors.[8] Alternatively, Haemophilus is sometimes cultured using the "Staph streak" technique: both Staphylococcus and Haemophilus organisms are cultured together on a single blood agar plate. In this case, Haemophilus colonies will frequently grow in small "satellite" colonies around the larger Staphylococcus colonies because the metabolism of Staphylococcus produces the necessary blood factor byproducts required for Haemophilus growth.

| Strain[9] | Needs hemin | Needs NAD | Hemolysis on HB/Rabbit blood |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. aegyptius | + | + | – |

| H. ducreyi | + | – | – |

| H. influenzae | + | + | – |

| H. haemolyticus | + | + | + |

| H. parainfluenzae | – | + | – |

| H. parahaemolyticus | – | + | + |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Genus: Haemophilus". lpsn.dsmz.de. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Holt JG, ed. (1994). Bergey's Manual of Determinative Bacteriology (9th ed.). Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-00603-7.

- ^ Kuhnert P; Christensen H, eds. (2008). Pasteurellaceae: Biology, Genomics and Molecular Aspects. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-34-9. [1].

- ^ a b Tortora, Gerard J; Funke, Berdell R; Case, Christine L (2016). Microbiology: An Introduction (12th ed.). Boston: Pearson. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-321-92915-0. OCLC 892055958.

- ^ Wang, Kun; Lu, Wenxin; Tu, Qichao; Ge, Yichen; He, Jinzhi; Zhou, Yu; Gou, Yaping; Nostrand, Joy D Van; Qin, Yujia; Li, Jiyao; Zhou, Jizhong; Li, Yan; Xiao, Liying; Zhou, Xuedong (10 March 2016). "Preliminary analysis of salivary microbiome and their potential roles in oral lichen planus". Scientific Reports. 6 (1) 22943. Bibcode:2016NatSR...622943W. doi:10.1038/srep22943. PMC 4785528. PMID 26961389.

- ^ Musher DM. Haemophilus Species. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 30. [2]Retrieved 29 Nov 2023.

- ^ "Haemophilus haemoglobinophilus and its laboratory diagnostics". Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ^ McPherson RA; Pincus MR, eds. (2011). Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods (22nd ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4377-0974-2.

External links

[edit]- Haemophilus chapter in Baron's Medical Microbiology (online at the NCBI bookshelf).

Haemophilus

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Classification

Etymology

The genus name Haemophilus derives from the Greek haîma (αἷμα), meaning "blood," and philos (φίλος), meaning "loving" or "friend," resulting in "blood-loving" to describe the bacteria's dependence on blood-derived growth factors for cultivation.[4] This nomenclature was formally established by Winslow et al. in 1917 when they proposed the genus to encompass certain hemophilic bacilli previously classified under other names.[5] The type species, Haemophilus influenzae, originated from earlier descriptions of influenza-associated bacteria; it was named Bacterium influenzae by Lehmann and Neumann in 1896 based on isolates from respiratory infections.[6] The epithet "influenzae" stems from the Latin genitive of influenza (Italian for "influence," referring to the disease), as the organism was erroneously identified as the primary cause of influenza pandemics in the late 19th century, a misconception first advanced by Richard Pfeiffer in 1892.[7] This association persisted despite later evidence that influenza is viral, leading to the species' reclassification into the Haemophilus genus by Winslow et al. in 1917.Phylogenetic Position

The genus Haemophilus is classified within the phylum Pseudomonadota, class Gammaproteobacteria, order Pasteurellales, and family Pasteurellaceae.[8] This placement reflects its membership in a diverse group of Gram-negative bacteria primarily associated with mucosal infections in animals and humans.[8] Phylogenetic analyses, particularly those based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, position Haemophilus firmly within the Pasteurellaceae family, highlighting its monophyletic core clade that includes species such as H. influenzae and H. parainfluenzae. These sequences reveal sequence similarities of approximately 93-97% with other Pasteurellaceae members, underscoring shared evolutionary origins while delineating genus boundaries.[9] Evolutionary divergence of Haemophilus from closely related genera like Pasteurella is evidenced by distinct genetic markers, including seven conserved signature indels (CSIs) exclusive to the Haemophilus sensu stricto group and variations in housekeeping genes such as rpoB and infB. Multilocus sequence analysis incorporating these markers confirms polyphyletic tendencies in broader Pasteurellaceae phylogenies but supports the integrity of the core Haemophilus lineage as a distinct evolutionary branch.Physical and Biochemical Characteristics

Morphology and Structure

Haemophilus species are Gram-negative bacteria exhibiting a coccobacillary morphology, characterized by short, rod-shaped or ovoid cells that appear pleomorphic under the microscope. These bacteria typically measure 0.3–0.5 μm in width and 0.5–1.0 μm in length, with rounded ends that contribute to their coccoid appearance in certain growth conditions. They are non-motile and lack spores, features that distinguish them from many other bacterial pathogens.[10][11] As Gram-negative organisms, Haemophilus possess a characteristic cell envelope consisting of an inner cytoplasmic membrane, a thin peptidoglycan layer in the periplasm (approximately 2–10 nm thick), and an outer membrane. The peptidoglycan layer provides structural integrity while remaining relatively sparse compared to Gram-positive bacteria, allowing flexibility in cell shape. The outer membrane is asymmetric, with phospholipids on the inner leaflet and lipooligosaccharides (LOS) on the outer leaflet; unlike full lipopolysaccharides in other Gram-negatives, LOS in Haemophilus lacks the repeating O-antigen polysaccharide chain, resulting in a shorter oligosaccharide structure that influences host immune interactions.[12][13] Certain Haemophilus strains, particularly encapsulated ones like Haemophilus influenzae type b, produce a polysaccharide capsule surrounding the cell. This capsule is composed of polyribosyl ribitol phosphate (PRP), a repeating polymer of ribose and ribitol-5-phosphate units, which forms a protective slime layer that resists phagocytosis and enhances virulence. Non-encapsulated strains lack this feature but may express other surface structures. Additionally, many Haemophilus isolates bear pili, thin proteinaceous filaments extending from the outer membrane, which mediate adherence to respiratory epithelial cells and mucus, facilitating colonization.[14][15]Growth Requirements

Haemophilus species are fastidious Gram-negative bacteria characterized by their dependence on specific exogenous growth factors for cultivation in vitro. Species in the genus require one or both of the X factor (hemin) and the V factor (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NAD+), which are essential for heme biosynthesis and electron transport, respectively, and are typically obtained from lysed red blood cells in enriched media.[1] Without these factors, Haemophilus cannot grow on unsupplemented nutrient agar, highlighting their obligate parasitic lifestyle adapted to nutrient-limited host environments.[1] Chocolate agar is the standard solid medium for isolating and growing Haemophilus, as heating blood to 80–90°C lyses erythrocytes and releases the bound X and V factors into the medium, supporting colony formation.[1] Similarly, Levinthal's broth, an enriched liquid medium containing hemoglobin, yeast extract, and other supplements, provides these factors and facilitates broth cultures for susceptibility testing or enumeration.[16] Some species, such as H. parainfluenzae, require only the V factor and can grow on blood agar, but most pathogenic members like H. influenzae demand both for robust proliferation.[1] Optimal growth of Haemophilus occurs at temperatures of 35–37°C, mimicking human body conditions, and in a microaerophilic or capnophilic atmosphere with 5–10% CO₂ to enhance factor utilization and prevent oxidative stress.[17] Incubation under these conditions typically yields visible colonies within 24–48 hours on appropriate media, underscoring the importance of precise environmental control for clinical and research applications.[1]Metabolism

Nutritional Needs

Haemophilus species exhibit specific nutritional dependencies critical for their metabolism, particularly an absolute requirement for heme (X factor) and NAD (V factor). Heme is essential for the synthesis of cytochromes involved in the electron transport chain, enabling aerobic respiration, as Haemophilus influenzae lacks the ability to produce protoporphyrin IX de novo. Similarly, NAD serves as a crucial cofactor in electron transport and other metabolic processes, with the bacterium unable to synthesize it due to the absence of key biosynthetic enzymes in the de novo pathway. These requirements are met in natural host environments through scavenging from host tissues or blood components. Carbon metabolism in Haemophilus primarily relies on simple sugars such as glucose, which is catabolized via respiration-assisted fermentation to generate energy and byproducts like acetate. Some strains display auxotrophies for specific amino acids, such as histidine, which impacts their growth and survival in nutrient-limited host sites like the middle ear. These auxotrophies arise from genetic variations that disrupt biosynthetic pathways, necessitating external supplementation for optimal proliferation. Iron acquisition is vital for Haemophilus pathogens, given the nutrient's role in heme incorporation and enzymatic functions. Pathogenic species, including nontypeable H. influenzae, employ multiple systems for iron uptake, such as direct heme scavenging and utilization of host transferrin-bound iron via specific receptors. Additionally, these strains possess loci for siderophore utilization, allowing them to exploit iron chelates produced by other microbes or the host, thereby enhancing survival in iron-restricted environments.Respiratory Pathways

Haemophilus species are facultative anaerobes that primarily generate energy through aerobic respiration, utilizing oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor in their electron transport chain (ETC).[18] The ETC in these bacteria involves membrane-bound components, including NADH dehydrogenases and a series of cytochromes, which facilitate the transfer of electrons from substrates like NADH to oxygen.[19] Key elements include cytochrome oxidases such as cytochromes a₁, o, and bd, which serve as terminal oxidases under aerobic conditions.[20] These heme-derived cytochromes, along with flavoproteins, form a branched respiratory system that enhances energy efficiency.[21] The composition of the ETC adapts to environmental oxygen levels; for instance, cytochrome bd oxidase expression increases under microaerobic conditions to maintain respiration.[18] This system supports a process often described as respiration-assisted fermentation, where oxidative phosphorylation complements substrate-level phosphorylation during glucose catabolism.[22] Heme, essential for the synthesis of these cytochrome components, underscores the bacterium's dependency on exogenous sources for optimal respiratory function.[21] Under low-oxygen or anaerobic conditions, Haemophilus shifts to fermentation pathways to regenerate NAD⁺, producing end products such as acetate and lactate.[23] Acetate is a predominant fermentation product, derived from acetyl-CoA via phosphate acetyltransferase and acetate kinase, while lactate forms through lactate dehydrogenase activity, albeit in smaller quantities.[18] This metabolic flexibility allows survival in oxygen-limited environments, such as host mucosal sites.[22]Habitat and Ecology

Natural Environments

Haemophilus species are primarily commensal bacteria residing on the mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory and genital tracts in humans and various animals, where they form part of the normal microbiota.[1] Despite this host dependency, rare instances of isolation from non-host sources have been documented, though free-living populations in abiotic environments like soil or water remain unestablished.[24] The fastidious nature of Haemophilus severely limits their environmental persistence, as they require specific growth factors such as hemin (factor X) and NAD (factor V), which are typically unavailable outside host tissues.[1] Consequently, these bacteria exhibit poor survival in natural non-host settings, with no routine detections reported from soil or aquatic ecosystems despite targeted sampling efforts.[24] For instance, extensive testing of water sources, including backwaters and lakes, failed to yield H. ducreyi isolates, underscoring their inability to thrive in such habitats.[24] Survival outside hosts is brief and highly sensitive to abiotic factors like humidity and temperature. Haemophilus species can persist in mucous for up to 18 hours and on inert surfaces such as plastic for approximately 12 hours under ambient conditions.[25][26] This susceptibility to environmental stressors further restricts their distribution beyond host-associated niches.[27]Host Associations

Haemophilus species are primarily associated with mammalian hosts, where they often exist as commensal or symbiotic bacteria in the upper respiratory tract. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi), the most common human-associated species, colonizes the nasopharynx and other mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract, beginning in infancy and persisting throughout life in many individuals. Colonization rates increase with age, reaching over 50% in children aged 5–6 years and more than 75% in healthy adults, with transmission occurring via airborne droplets and close contact. This commensal relationship allows NTHi to adhere to epithelial cells using adhesins such as HMW1/HMW2 and Protein E, which bind to extracellular matrix components like laminin, facilitating stable mucosal colonization without typically causing harm in healthy hosts.[28][29] In veterinary contexts, Haemophilus parasuis exhibits similar host associations with pigs, serving as an early colonizer of the upper respiratory tract in healthy swine. This bacterium is frequently isolated from the nasal passages, tonsils, and trachea of pigs in swine-rearing regions worldwide, establishing a commensal presence that modulates with host immune factors like serum antibodies. Non-virulent strains of H. parasuis contribute to the porcine respiratory microbiome, where they interact with innate defenses such as alveolar macrophages, maintaining a balanced symbiotic dynamic in the absence of stressors.[30] A key mechanism enhancing Haemophilus persistence in these host associations is biofilm formation on mucosal epithelia. NTHi and related species produce adherent biofilms on the apical surfaces of airway epithelial cells, incorporating components like sialylated exopolysaccharides and extracellular DNA to create structured communities up to 20 μm deep. These biofilms promote long-term colonization by reducing susceptibility to host clearance mechanisms and antibiotics, as demonstrated in in vitro models using polarized epithelial monolayers, thereby supporting chronic commensalism in the nasopharynx and porcine airways.[31][29]Diversity and Species

List of Recognized Species

The genus Haemophilus currently encompasses approximately 13 recognized species that remain validly published and classified within it, primarily based on 16S rRNA gene sequencing, whole-genome analyses, and phenotypic characteristics such as growth factor requirements (X-factor: hemin; V-factor: NAD), oxidase activity, and hemolysis patterns. These species are fastidious, Gram-negative coccobacilli belonging to the family Pasteurellaceae, with most requiring supplemented media for cultivation. Type strains are typically deposited in culture collections like NCTC (National Collection of Type Cultures) or ATCC (American Type Culture Collection), and distinguishing tests often include satellite growth around Staphylococcus (for V-factor dependency), porphyrin synthesis, and urease activity. Recent taxonomic revisions have reduced the number of species in Haemophilus from over 20 historically named taxa, with several reclassified to new genera like Aggregatibacter (e.g., former H. actinomycetemcomitans, H. aphrophilus, and H. segnis in 2006 based on phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic data) due to distinct genomic signatures and host associations.[32] The following table enumerates the current recognized species in Haemophilus, including key details on host, growth requirements, notable biochemical traits, and type strains. This list reflects updates as of 2025, excluding reclassified taxa.| Species Name | Original Description (Year, Author) | Primary Host | Growth Requirements | Key Biochemical Tests | Type Strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. influenzae | (Lehmann and Neumann 1896) Winslow et al. 1917 | Humans (respiratory tract) | X- and V-factors required | Oxidase +, catalase +, non-hemolytic, indole -; 6 capsular serotypes (a-f) | NCTC 8143 (ATCC 33391) |

| H. parainfluenzae | Rivers 1922 (Approved Lists 1980) | Humans (oropharyngeal) | V-factor only | Oxidase +, catalase +, non-hemolytic, indole + | NCTC 8479 (ATCC 7901) |

| H. ducreyi | (Augustin 1909) Bergey et al. 1925 | Humans (genital ulcers) | X-factor only | Oxidase + (variable), catalase -, non-hemolytic, urease variable; microaerophilic | NCTC 10945 (ATCC 33940) |

| H. haemolyticus | (Thjotta and Boe 1938) Winslow et al. 1940 | Humans (respiratory) | X- and V-factors required | Oxidase +, catalase +, β-hemolytic, often misidentified as H. influenzae | NCTC 10659 (ATCC 33390) |

| H. parahaemolyticus | (Tunnicliff 1942) Breed et al. 1948 | Humans (pharyngitis) | V-factor only | Oxidase +, catalase +, β-hemolytic, urease - | NCTC 8477 (ATCC 10046) |

| H. paraphrohaemolyticus | Murphy and Gwynn 1983 | Humans (respiratory) | V-factor only | Oxidase +, catalase +, β-hemolytic; ferments sucrose | NCTC 11413 (ATCC 51150) |

| H. pittmaniae | Nørskov-Lauritsen et al. 2005 (validated 2020) | Humans (saliva, respiratory) | V-factor only | Oxidase +, catalase +, β-hemolytic, urease +; named after Marge Pittman | CCUG 57076 (DSM 25380) |

| H. sputorum | Nørskov-Lauritsen et al. 2005 (validated 2020) | Humans (oral cavity) | V-factor only | Oxidase +, catalase +, β-hemolytic; produces acetoin | CCUG 57077 (DSM 25381) |

| H. aegyptius | (Trevisan 1889) Pittman and Davis 1950 | Humans (conjunctiva) | X- and V-factors required | Oxidase +, catalase +, non-hemolytic; biovar of H. influenzae but distinct in eye tropism | NCTC 8502 (ATCC 11116) |

| H. felis | Kilian et al. 1989 | Cats (respiratory) | X- and V-factors required | Oxidase +, catalase +, non-hemolytic, indole -; occasional zoonotic potential | NCTC 10391 (ATCC 49728) |

| H. piscium | Snieszko 1945 (Approved Lists 1980) | Fish (aquatic infections) | X-factor only | Oxidase -, catalase variable, non-hemolytic; grows at 22°C | NCTC 8372 (ATCC 11137) |

| H. paracuniculus | Boot et al. 1993 | Rabbits (nasal) | X- and V-factors required | Oxidase +, catalase +, non-hemolytic; ferments dulcitol | ATCC 51786 |

| H. seminalis | Li et al. 2020 | Humans (genital tract/semen) | V-factor only | Oxidase +, catalase +, non-hemolytic | CGMCC 1.17279 (DSM 110435) |