Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cytochrome

View on Wikipedia

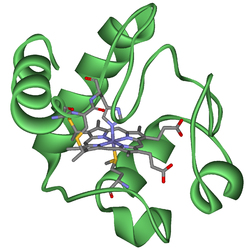

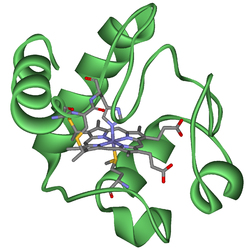

Cytochromes are redox-active proteins containing a heme, with a central iron (Fe) atom at its core, as a cofactor. They are involved in the electron transport chain and redox catalysis. They are classified according to the type of heme and its mode of binding. Four varieties are recognized by the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (IUBMB), cytochromes a, cytochromes b, cytochromes c and cytochrome d.[1]

Cytochrome function is linked to the reversible redox change from ferrous (Fe(II)) to the ferric (Fe(III)) oxidation state of the iron found in the heme core.[2] In addition to the classification by the IUBMB into four cytochrome classes, several additional classifications such as cytochrome o[3] and cytochrome P450 can be found in biochemical literature.

History

[edit]Cytochromes were initially described in 1884 by Charles Alexander MacMunn as respiratory pigments (myohematin or histohematin).[4] In the 1920s, Keilin rediscovered these respiratory pigments and named them the cytochromes, or “cellular pigments”.[5] He classified these heme proteins on the basis of the position of their lowest energy absorption band in their reduced state, as cytochromes a (605 nm), b (≈565 nm), and c (550 nm). The ultra-violet (UV) to visible spectroscopic signatures of hemes are still used to identify heme type from the reduced bis-pyridine-ligated state, i.e., the pyridine hemochrome method. Within each class, cytochrome a, b, or c, early cytochromes are numbered consecutively, e.g. cyt c, cyt c1, and cyt c2, with more recent examples designated by their reduced state R-band maximum, e.g. cyt c559.[6]

Structure and function

[edit]The heme group is a highly conjugated ring system (which allows its electrons to be very mobile) surrounding an iron ion. The iron in cytochromes usually exists in a ferrous (Fe2+) and a ferric (Fe3+) state with a ferroxo (Fe4+) state found in catalytic intermediates.[1] Cytochromes are, thus, capable of performing electron transfer reactions and catalysis by reduction or oxidation of their heme iron. The cellular location of cytochromes depends on their function. They can be found as globular proteins and membrane proteins.

In the process of oxidative phosphorylation, a globular cytochrome cc protein is involved in the electron transfer from the membrane-bound complex III to complex IV. Complex III itself is composed of several subunits, one of which is a b-type cytochrome while another one is a c-type cytochrome. Both domains are involved in electron transfer within the complex. Complex IV contains a cytochrome a/a3-domain that transfers electrons and catalyzes the reaction of oxygen to water. Photosystem II, the first protein complex in the light-dependent reactions of oxygenic photosynthesis, contains a cytochrome b subunit. Cyclooxygenase 2, an enzyme involved in inflammation, is a cytochrome b protein.

In the early 1960s, a linear evolution of cytochromes was suggested by Emanuel Margoliash[7] that led to the molecular clock hypothesis. The apparently constant evolution rate of cytochromes can be a helpful tool in trying to determine when various organisms may have diverged from a common ancestor.[8]

Types

[edit]Several kinds of cytochrome exist and can be distinguished by spectroscopy, exact structure of the heme group, inhibitor sensitivity, and reduction potential.[9]

Four types of cytochromes are distinguished by their prosthetic groups:

| Type | Prosthetic group |

|---|---|

| Cytochrome a | heme A |

| Cytochrome b | heme B |

| Cytochrome c | heme C (covalently bound heme b)[10] |

| Cytochrome d | heme D (Heme B with γ-spirolactone)[11] |

There is no "cytochrome e," but cytochrome f, found in the cytochrome b6f complex of plants is a c-type cytochrome.[12]

In mitochondria and chloroplasts, these cytochromes are often combined in electron transport and related metabolic pathways:[13]

| Cytochromes | Combination |

|---|---|

| a and a3 | Cytochrome c oxidase ("Complex IV") with electrons delivered to complex by soluble cytochrome c (hence the name) |

| b and c1 | Coenzyme Q - cytochrome c reductase ("Complex III") |

| b6 and f | Plastoquinol—plastocyanin reductase |

A distinct family of cytochromes is the cytochrome P450 family, so named for the characteristic Soret peak formed by absorbance of light at wavelengths near 450 nm when the heme iron is reduced (with sodium dithionite) and complexed to carbon monoxide. These enzymes are primarily involved in steroidogenesis and detoxification.[14][9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry (NC-IUB). Nomenclature of electron-transfer proteins. Recommendations 1989". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 267 (1): 665–677. 1992-01-05. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)48544-4. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 1309757.

- ^ L., Lehninger, Albert (2000). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1572591530. OCLC 42619569.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Puustinen, A.; Wikström, M. (1991-07-15). "The heme groups of cytochrome o from Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 88 (14): 6122–6126. Bibcode:1991PNAS...88.6122P. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.14.6122. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 52034. PMID 2068092.

- ^ Mac Munn, C. A. (1886). "Researches on Myohaematin and the Histohaematins". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 177: 267–298. doi:10.1098/rstl.1886.0007. JSTOR 109482. S2CID 110335335.

- ^ Keilin, D. (1925-08-01). "On cytochrome, a respiratory pigment, common to animals, yeast, and higher plants". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 98 (690): 312–339. Bibcode:1925RSPSB..98..312K. doi:10.1098/rspb.1925.0039. ISSN 0950-1193.

- ^ Reedy, C. J.; Gibney, B. R. (February 2004). "Heme protein assemblies". Chem Rev. 104 (2): 617–49. doi:10.1021/cr0206115. PMID 14871137.

- ^ Margoliash, E. (1963). "Primary Structure and Evolution of Cytochrome C". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 50 (4): 672–679. Bibcode:1963PNAS...50..672M. doi:10.1073/pnas.50.4.672. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 221244. PMID 14077496.

- ^ Kumar, Sudhir (2005). "Molecular clocks: four decades of evolution". Nature Reviews. Genetics. 6 (8): 654–662. doi:10.1038/nrg1659. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 16136655. S2CID 14261833.

- ^ a b "Investigation of biological oxidation, oxidative phosphorylation and ATP synthesis. Inhibitor and Uncouplers of oxidative phosphorylation". Archived from the original on 2020-06-28. Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- ^ Cytochrome+c+Group at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH).

- ^ Murshudov, G.; Grebenko, A.; Barynin, V.; Dauter, Z.; Wilson, K.; Vainshtein, B.; Melik-Adamyan, W.; Bravo, J.; Ferrán, J.; Ferrer, J. C.; Switala, J.; Loewen, P. C.; Fita, I. (1996). "Structure of the heme d of Penicillium vitale and Escherichia coli catalases". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (15): 8863–8868. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.15.8863. PMID 8621527.

- ^ Bendall, Derek S. (2004). "The Unfinished Story of Cytochrome f". Photosynthesis Research. 80 (1–3): 265–276. doi:10.1023/b:pres.0000030454.23940.f9. ISSN 0166-8595. PMID 16328825. S2CID 16716904.

- ^ Doidge, Norman (2015). The brain's way of healing : remarkable discoveries and recoveries from the frontiers of neuroplasticity. Penguin Group. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-698-19143-3.

- ^ Miller, Walter L.; Gucev, Zoran S. (2014), "Disorders in the Initial Steps in Steroidogenesis", Genetic Steroid Disorders, Elsevier, pp. 145–164, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-416006-4.00011-9, ISBN 9780124160064

External links

[edit]- Scripps Database of Metalloproteins

- Cytochromes at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Cytochrome

View on Grokipedia- Cytochrome a: Contains heme a (a derivative of protoporphyrin IX with a formyl side chain), bound via coordination to protein residues; α-band at 580–590 nm; ether-soluble; key examples include cytochromes a and a₃ in the cytochrome c oxidase complex (complex IV) of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, where they accept electrons from cytochrome c and reduce molecular oxygen to water.[2][1]

- Cytochrome b: Features protoheme (iron protoporphyrin IX) non-covalently bound to the protein; α-band at 556–558 nm; ether-soluble; involved in early steps of electron transport, such as in the cytochrome b-c₁ complex (complex III), which transfers electrons from ubiquinol to cytochrome c while pumping protons across the membrane.[2][1]

- Cytochrome c: Contains protoheme covalently attached via thioether bonds to cysteine residues in the protein; α-band at 549–551 nm (for two thioether links) or around 553 nm (for one link); insoluble in ether; exemplified by cytochrome c, a small soluble protein that shuttles electrons between complexes III and IV in the mitochondrial inner membrane, and also plays roles in photosynthesis and apoptosis signaling.[2][1]

- Cytochrome d: Incorporates a modified heme such as heme d or d₁ with reduced porphyrin ring conjugation (dihydroporphyrin or tetrahydroporphyrin); α-band at 600–620 nm; variable solubility; typically found in bacterial oxidases that reduce oxygen under low-oxygen conditions.[2]