Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

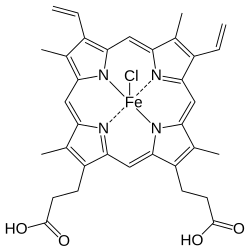

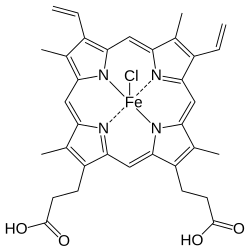

Hemin

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous infusion |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.036.475 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C34H32ClFeN4O4 |

| Molar mass | 651.95 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Hemin (haemin; ferric chloride heme) is an iron-containing porphyrin with chlorine that can be formed from a heme group, such as heme B found in the hemoglobin of human blood.

Chemistry

[edit]Hemin is protoporphyrin IX containing a ferric iron (Fe3+) ion with a coordinating chloride ligand.

Hemin is a dark brown solid that is almost insoluble in water, but soluble in alkaline aqueous solutions to form a dark green aqueous solution of hematin.

Chemically, hemin differs from the related heme-compound hematin chiefly in that the coordinating ion is a chloride ion in hemin, whereas the coordinating ion is a hydroxide ion in hematin.[2] The iron ion in haem is ferrous (Fe2+), whereas it is ferric (Fe3+) in both hemin and hematin.

Hemin is endogenously produced in the human body, for example during the turnover of old red blood cells. It can form inappropriately as a result of hemolysis or vascular injury. Several proteins in human blood bind to hemin, such as hemopexin and serum albumin.

Hemin reacts with hydrogen cyanide in ammonia solution to form a blood-red complex.

Pharmacological use

[edit]A lyophilised form of hemin is used as a pharmacological agent in certain cases for the treatment of porphyria attacks, particularly in acute intermittent porphyria. Administration of hemin can reduce heme deficits in such patients, thereby suppressing the activity of delta-amino-levulinic acid synthase (a key enzyme in the synthesis of the porphyrins) by biochemical feedback, which in turn reduces the production of porphyrins and of the toxic precursors of heme. In such pharmacological contexts, hemin is typically formulated with human albumin prior to administration by a medical professional, to reduce the risk of phlebitis and to stabilize the compound, which is potentially reactive if allowed to circulate in free-form. Such pharmacological forms of hemin are sold under a range of trade names including the trademarks Panhematin[3] and Normosang.[4]

History of isolation

[edit]Hemin was first crystallized out of blood in 1853, by Ludwik Karol Teichmann. Teichmann discovered that blood pigments can form microscopic crystals. Thus, crystals of hemin are occasionally referred to as 'Teichmann crystals'. Hans Fischer synthesized hemin, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1930.[5] Fischer's procedure involves treating defibrinated blood with a solution of sodium chloride in acetic acid.[6]

Forensics

[edit]Hemin can be produced from hemoglobin by the so-called Teichmann test, when hemoglobin is heated with glacial acetic acid (saturated with saline). This can be used to detect blood traces.

Other

[edit]Hemin is considered the "X factor" required for the growth of Haemophilus influenzae.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary for Panhematin". 23 October 2014.

- ^ Grenoble DC, Drickamer HG (December 1968). "The effect of pressure on the oxidation state of iron. 3. Hemin and hematin" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 61 (4): 1177–82. Bibcode:1968PNAS...61.1177G. doi:10.1073/pnas.61.4.1177. PMC 225235. PMID 5249803.

- ^ "Panhematin for Acute Porphyria". American Porphyria Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Normosang". Electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC).

- ^ Fischer H. "On hemin and the relationships between hemin and chlorophyll" (PDF). Nobel Lecture. Nobel Prize Foundation.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Fischer H (1941). "Hemin". Org. Synth. 21: 53. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.021.0053.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - ^ Sherris JC, Ryan KJ, Ray CL (2004). Sherris medical microbiology: an introduction to infectious diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 395. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

External links

[edit]- Hemin at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)