Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

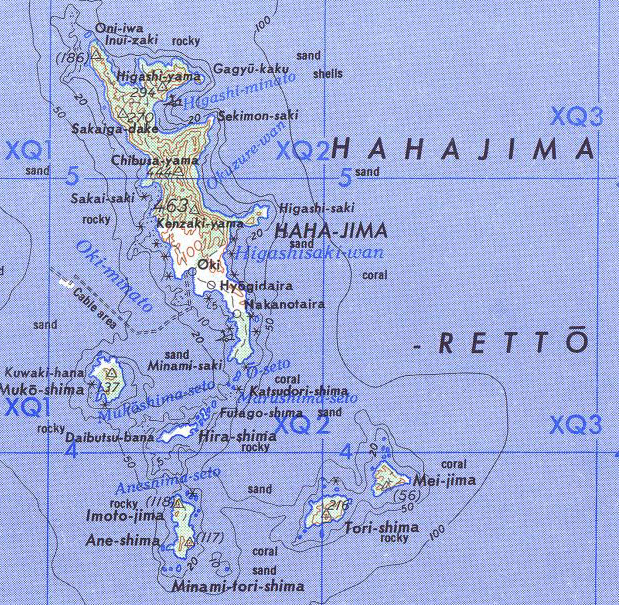

Hahajima

View on WikipediaHahajima, Haha Jima, or Haha-jima (母島; meaning Mother Island) is the second-largest island within the Bonin or Ogasawara Islands SSE of the Japanese Home Islands. The steeply-sloped island, which is about 21 km2 (8 sq mi) in area, has a population of 440.[1] It is part of Ogasawara Village in Ogasawara Subprefecture, which is approximately 1,000 km (620 mi) south of Tokyo, Japan.

Key Information

The highest peaks Hahajima are Chibusayama (lit. Breast Mountain), approximately 462 metres (1,516 ft), and Sakaigatake, 443 metres (1,453 ft). It is part of an archipelago that includes Chichijima approximately 50 km (31 mi) to the north and the nearby smaller islands such as Anejima and Imōtojima and Mukōjima. The group forms the Hahajima Rettō (母島列島; formerly the "Baily Group").

History

[edit]

Micronesian tools and carvings suggest prehistoric visits or settlement but the island was long uninhabited before its rediscovery, sometimes—but probably mistakenly[2]—credited to Bernardo de la Torre during his failed 1543 attempt to find a northern route back to Mexico from the Philippines. Captain James Coffin, of the whaler Transit originally named the largest island in the group "Fisher Island", which became Hahajima, and the second largest "Kidd Island", after the owners of his vessel. The islands came to be known as the "Coffin Islands". (Hahajima was also called Hillsborough Island.) Hahajima was settled by Europeans before becoming part of Japan.

During the Pacific War, the Japanese government removed the local civilian population and fortified the island. It was attacked several times by the US bombers. First on December 4, 1944 when Navy search planes of Fleet Air Wing One joined with Seventh Air Force bombers to attack installations on the island as well as Iwo Jima. Four days later there was another attack by Fleet Air Wing One. Then on December 10, B-25 Mitchells from the 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing struck at shipping moored at Hahajima.[3] The remains of defensive fortifications are now one of the island's tourist attractions.

The population, which was 1,546 in 1904 and 1,905 in 1940, is now only 450. A single road connects the abandoned village of Kitamura (北村) at the north end of the island to the village of Okimura (沖村) – formerly "Newport", at the southern end of the island, where the harbor is located. The island can be reached by ferry in about two hours from Chichijima. The economy of Hahajima is based on commercial fishing, tourism as well as a state-run rum distillery.

Education

[edit]

Ogasawara Village operates the island's public elementary and junior high school, Ogasawara Village Municipal Haha-jima Elementary School and Junior High School (小笠原村立母島小中学校).[4] Tokyo Metropolitan Government Board of Education operates Ogasawara High School[1] Archived 2020-02-15 at the Wayback Machine on nearby Chichijima.

Ecology

[edit]Hahajima is of considerable interest to malacologists because of its endemic land snail fauna, including the eponymous Lamprocystis hahajimana. Due to the widespread presence of invasive species including goats (which destroy habitat) and rodents, flatworms and the rosy wolfsnail (which eat the native snails), it was feared that many of the endemics had become extinct.[5]

But most if not all of the endemic land snail species seem to persist on the remote Higashizaki peninsula on the eastern coast. This is a quite pristine expanse of ground, scenic but very hard to reach (one has to climb Mt. Chibusa before descending to the peninsula). It consists of sheer seacliffs surrounding a plateau with Chinese fan palm (Livistona chinensis), pandanus and broadleaf (e.g. Persea kobu, a wild avocado) forest, and appears to be untouched by invasive species at present. It has been proposed that access to the area should be monitored, so that visitors will not inadvertently contribute to destroying this unique area.[5]

Snails

[edit]All of these snails are endemic at least to the Bonin Islands.

- Boninena callistoderma – Endangered, now restricted to Hahajima and nearby Anejima[5]

- Gastrocopta boninensis – Vulnerable

- Hirasea acutissima – Endangered (believed extinct, rediscovered 2003), endemic to Hahajima[5]

- Lamellidea biplicata – Vulnerable

- Lamprocystis hahajimana – Endangered

- Mandarina hahajimana – Data deficient, possibly a new taxon[5]

- Mandarina polita – Data deficient

- Ogasawarana yoshiwarana – Critically endangered (believed extinct, rediscovered 2003), endemic to Hahajima[5]

- Ogasawarana arata – Data deficient

- Paludinella minima – Data deficient

- Vertigo dedecora – Vulnerable

- Tornatellides tryoni

Birds

[edit]Among birds, the Bonin white-eye (Apalopteron familiare), a gaudy-colored passerine, now only occurs on Hahajima.[6] The extinct Bonin grosbeak (Chaunoproctus ferreorostris) is sometimes said to have occurred in the Hahajima Group (though not on Haha-jima itself), but this seems not to be true. Columba janthina nitens, the Bonin subspecies of the Japanese wood-pigeon, used to occur on Haha-jima. While it is not precisely known when it vanished from this island,[7] the taxon apparently became completely extinct during the 1980s, but was rediscovered in 1998. The island has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International.[8]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "支庁の案内: 管内概要 (Japanese)". 2021-04-01. Retrieved 2022-06-16.

- ^ Welsch (2004).

- ^ "CINCPAC COMMUNIQUÉ, DECEMBER 1944". www.ibiblio.org. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- ^ "学校教育 Archived 2018-03-09 at the Wayback Machine." Ogasawara, Tokyo. Retrieved on March 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Chiba et al. (2007)

- ^ "Apalopteron familiare". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

- ^ Hume, Julian P. (2017). Extinct Birds. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 495. ISBN 9781472937469.

- ^ "Hahajima islands". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chiba, Satoshi; Davison, Angus & Mori, Hideaki (2007): Endemic Land Snail Fauna (Mollusca) on a Remote Peninsula in the Ogasawara Archipelago, Northwestern Pacific. Pacific Science 61(2): 257–265. DOI: 10.2984/1534-6188(2007)61[257:ELSFMO]2.0.CO;2 HTML abstract

- Welsch, Bernhard (June 2004), "Was Marcus Island Discovered by Bernardo de la Torre in 1543?", Journal of Pacific History, vol. 39, Milton Park: Taylor & Francis, pp. 109–122, doi:10.1080/00223340410001684886, JSTOR 25169675, S2CID 219627973.