Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Human Highway

View on Wikipedia

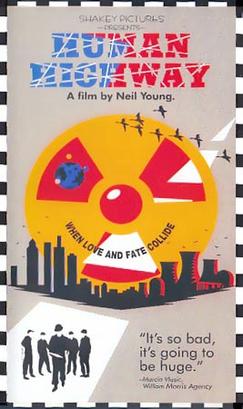

| Human Highway | |

|---|---|

VHS cover | |

| Directed by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | David Myers |

| Edited by | James Beshears |

| Music by |

|

Production company | Shakey Pictures |

| Distributed by | Warner Reprise Video |

Release date |

|

Running time | 88 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Human Highway is a 1982 American comedy film starring and co-directed by Neil Young in his film and directional debut under his pseudonym Bernard Shakey. Dean Stockwell co-directed the film and acted along with Russ Tamblyn, Dennis Hopper, and the band Devo. Included is a collaborative performance of "Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)" by Devo and Young with Booji Boy singing lead vocals and Young playing lead guitar.

The film was shown in select theaters and not released on VHS until 1995. It received poor reviews upon its premiere[1] but has received favorable reviews more recently.[2]

Plot

[edit]Employees and customers spend time at a small gas station-diner in a fictional town next to a nuclear power plant unaware it is the last day on Earth. Young Otto Quartz has received ownership of the failing business in his recently deceased father's will. His employee, Lionel Switch, is the garage's goofy and bumbling auto mechanic who dreams of being a rock star. "I can do it!" Lionel often exclaims. After some modest character development and a collage-like dream sequence there is a tongue-in-cheek choreographed musical finale while nuclear war begins.

At the destroyed gas station-diner post nuclear holocaust, Booji Boy is the lone survivor, but after his cynical prose[3] the opening credits are a return to the present. (Some edits of the film place this scene at the end, including the most recent director's cut.)

At the nuclear power plant nuclear garbage men (members of Devo) reveal that radioactive waste is routinely mishandled and dumped at the nearby town of Linear Valley. They sing a remake of "Worried Man Blues" while loading waste barrels on an old truck. Meanwhile, Lionel and his buddy Fred Kelly (Russ Tamblyn) ride bicycles to work. Fred says that Old Otto's recent death was by radiation poisoning. They remain unaware of the implications as Lionel laments it should have been he who died because he has worked on "almost every radiator in every car in town."

Early in the day at the diner Young Otto announces he must fire an employee for lack of money. He chooses waitress Kathryn, who has a tantrum and refuses to leave. She sits down weeping at a booth that has a picture on the wall of Old Otto and chooses on the jukebox the song "The End of the World". Later, waitress Irene overhears Young Otto's plans to fire everybody, destroy the buildings, and collect on a fraud insurance claim. Irene demands to be included in the scheme and to seal the deal with a kiss.

Although Lionel has a crush on the waitress Charlotte Goodnight, she has a crush on the milkman Earl Duke. After an earthquake Duke, dressed in white, enters the diner with a delivery. He flirts with her saying, "Charlotte ...on my way over here this morning I thought about you and the earth moved." She replies, "You felt it too!" He also offers her a milk bath. While he is there a dining Arab sheik offers him wealth in return for his "whiteness."

A limousine stops at the gas station. After Lionel learns his rock star idol, Frankie Fontaine, is in the limousine he insists the vehicle will need work. After meeting Frankie, who appears to lead an opulent, sequestered and drug-influenced lifestyle, Lionel says to the wooden Indian in his shop, "Now there's a real human being!"

Lionel receives a bump on the head while working on Frankie's limousine and enters a dream. He becomes a rock star with a backup band of wooden Indians. Backstage he is given a milk bath by Irene. Lionel travels with his band (the wooden Indians) and crew (all people from his waking life) by trucks through the desert. The wooden Indians go missing.

During "Goin' Back" (a song by Young) the entourage recreates in the desert near a Pueblo. Native Americans prepare a bonfire to burn the wooden Indians that went missing. Soon Lionel is playing music and dancing around the bonfire, which appears to have become the center of a Pow-wow. "Goin' Back" ends gazing into the bonfire of burning wooden Indians. "Hey, Hey, My, My" is a ten-minute studio jam performance by Devo and Young.

Lionel wakes from his dream surrounded by concerned friends, much like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. Soon, global nuclear war begins. No one is sure what is happening until it is announced by Booji Boy as "the hour of sleep." He provides shovels and commands everyone to "dig that hole and dance like a mole!" The cast then enters a choreographed adaptation of "Worried Man". The planet is engulfed in radioactive glow and the cast, still festive, climbs a stairway to heaven accompanied by harp music.

Cast

[edit]- Neil Young as Lionel Switch, the garage mechanic

- Russ Tamblyn as Fred Kelly, Lionel's friend

- Dean Stockwell as Otto Quartz, the restaurant and gas station owner

- Dennis Hopper as Cracker, the cook

- Charlotte Stewart as Charlotte

- Sally Kirkland as Kathryn

- Geraldine Baron as Irene.[4]

- Devo as Nuclear Garbagepersons

- Mark Mothersbaugh also plays recurring Devo character Booji Boy

- Pegi Young as Biker Girl

- Mickey Fox as Mrs. Robinson

- Fox Harris as Sheik

- David Blue as Earl Duke, the milkman[5] The role was Blue's final credit.

Several of the cast members became favorites of David Lynch.[6]

Production

[edit]Over four years Young spent $3 million of his own money on production.[1] Filming began in 1978 in San Francisco and Taos, New Mexico. It was resumed in 1981 on the Hollywood soundstages of Raleigh Studios. The set, which included the diner and gas station, was built to Young's specific requests. His initial idea was to portray a day in the life of Lionel and bystanders during the Earth's last day. The actors were to develop their own characters.[7] The script was a combination of improvisation and developing small story lines as they went. Young, Stockwell, and Tamblyn were central in the writing.[1]

Dennis Hopper, who played the addled cook, was performing knife tricks with a real knife on the set. Sally Kirkland attempted to take a knife from him and severed a tendon. She spent time in a hospital and later sued, claiming Hopper was out of control. Hopper has admitted to drug abuse during this period.[1]

It was Devo's first experience with Hollywood. Gerald Casale said the band felt removed observing the odd behavior, including excessive alcohol and drug abuse, and rock star adulation with Young as the central "most grounded" person.[7]

The "Hey Hey My My" footage with Devo was recorded at Different Fur, San Francisco. Mark Mothersbaugh as "Booji Boy" during this performance inserted the Devo line, "rust never sleeps". The line inspired Young's works of the same name. Young showed the footage of this performance to his band Crazy Horse. Guitarist Frank Sampedro has said they played "Hey Hey My My" "harder" as a result.[8]

Credits

[edit]Editing and post-production supervision is credited to James Beshears (Madagascar, Shark Tale, Shrek). The screenplay is credited to Bernard Shakey, Jeanne Field, Dean Stockwell, Russ Tamblyn, and Beshears.[9] The members of Devo were asked to write their own parts.[10] Choreography is credited to Tamblyn. Music is credited to Young and Devo.[9] The film's score was the first by Mark Mothersbaugh (Rugrats, Nick and Norah's Infinite Playlist, Herbie: Fully Loaded, Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, The Lego Movie), who also portrays Booji Boy and a nuclear garbage man.[10] Most of the songs by Young in the film were released on the album Trans.[9][11]

Release

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]Human Highway is commonly reviewed as a "bizarre" comedy.[12] After its June 1983 premiere in Los Angeles, it was shown only briefly in a small number of theaters. It received poor reviews from critics[1] and confused audiences.[12] Since its release on VHS in 1996 it has received more favorable reviews. TV Guide called it "goofy and enjoyable" and Young's acting "surprisingly funny." TV Guide also suggested that the film would have done well on the midnight circuit that existed at the time of its release.[6] One critic of cult films called the film self-absorbed and worthwhile only for completists.[13] Young's intention to reference the dream-plot of The Wizard of Oz[1] is recognized in a Rotten Tomatoes synopsis describing the film as "The Wizard of Oz on acid."[14] A more recent review by Seattle Times critic Tom Keogh notes the film's use of "hyper-real sets" predating Tim Burton and a surety of direction at times recognizably influenced by Paul Morrissey and John Waters.[2]

Home video

[edit]The film was released in a VHS fullscreen edition (as well as LaserDisc) by WEA in 1995, twelve years after its initial screening. A DVD and Blu-Ray of Neil's "Directors Cut" was released July 22, 2016, alongside a DVD and Blu-Ray release of the Rust Never Sleeps concert film. It was a different edit than the theatrical release, in addition to being eight minutes shorter. The dream sequence originally featured a concert version of "Ride My Llama", while the 1995 version replaced it with the album version of "Goin' Back". Several scenes from the movie appeared on the Devo music video collections We're All Devo and The Complete Truth About Devolution, and were edited to appear as one continuous video for the song "Worried Man".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Jimmy McDonough, Shakey, Anchor Books, 2002, p.575-7

- ^ a b c Tom Keogh Review at IMDb Retrieved September 1, 2007

- ^ The prose is excerpted from "My Struggle", by Booji Boys, 1978. Film credits.

- ^ Film credits.

- ^ Obituary David Blue, Singer-Actor, 41, Was Part of 60's Folk Revival The New York Times, December 7, 1982

- ^ a b Human Highway TV Guide. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Jimmy McDonough, Shakey, Anchor Books, 2002, p.528-9

- ^ Jimmy McDonough, Shakey, Anchor Books, 2002, p.531-2

- ^ a b c Film credits

- ^ a b Interview: Mark Mothersbaugh on soundtracks, surf and Devo Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine Don Zulaica, liveDaily.com, April 25, 2001 Retrieved September 5, 2007

- ^ Liner notes from Trans

- ^ a b Mark Demming Human Highway allmovie.com

- ^ Steven Puchalski Human Highway shockcinemamagazine.com, 1989.

- ^ Human Highway Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

External links

[edit]Human Highway

View on GrokipediaSynopsis

Plot summary

Human Highway is set in the fictional town of Linear Valley, adjacent to a malfunctioning nuclear power plant operated by the Cal-Neva Nuclear Power Authority. The narrative centers on the struggling roadside diner and gas station inherited by Otto Quartz (Dean Stockwell), who schemes to arson the establishment for insurance money amid economic pressures like gas wars.[7][1] Employees, including mechanics Lionel Switch (Neil Young) and Fred (Russ Tamblyn), handle routine repairs while waitress Charlotte serves customers; meanwhile, Devo band members portray plant workers in red jumpsuits who dump radioactive waste and perform maintenance tasks.[5][1] The story unfolds in a non-linear, dreamlike fashion, interweaving daily operations with hallucinatory sequences triggered when Lionel is knocked unconscious. In his visions, Lionel fantasizes about rock stardom, including a surreal tour as a roadie-turned-performer, bathing in milk, and jamming with Devo—highlighted by Booji Boy's rendition of "Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)."[1][5] Apocalyptic elements escalate with leaking radiation, radioactive flies, and atomic test imagery, culminating in a nuclear meltdown that destroys the town. Survivors emerge in a post-apocalyptic wasteland for a musical finale, dancing with shovels while performing "Worried Man Blues."[7][1]Cast and characters

Principal cast

Neil Young portrays the dual roles of Lionel Switch, a mechanic at a roadside garage, and Frankie Fontaine, in what constituted his first major acting role in a feature film.[8][9] Dean Stockwell plays Otto Quartz, the proprietor of a diner and adjacent gas station, while also serving as co-director alongside Young.[8][10] Russ Tamblyn appears as Fred Kelly, Switch's fellow mechanic and friend at the garage.[8] Dennis Hopper takes on the role of Cracker, an erratic cook, in addition to other minor characters improvised during production.[8][1]| Actor | Role(s) |

|---|---|

| Neil Young | Lionel Switch / Frankie Fontaine |

| Dean Stockwell | Otto Quartz |

| Russ Tamblyn | Fred Kelly |

| Dennis Hopper | Cracker / Stranger |