Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Farm Aid

View on Wikipedia

| Farm Aid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | United States |

| Years active | 1985–present |

| Founders | Willie Nelson, John Mellencamp and Neil Young |

| Website | Official website |

Farm Aid is a benefit concert held nearly every year since 1985 for American farmers.

History

[edit]On July 13, 1985, before performing "When The Ship Comes In" with Keith Richards and Ron Wood at the Live Aid benefit concert for the 1983–1985 Ethiopian famine, Bob Dylan remarked about family farmers within the United States in danger of losing their farms through mortgage debt, saying to the worldwide audience exceeding one billion people, "I hope that some of the money ... maybe they can just take a little bit of it, maybe ... one or two million, maybe ... and use it, say, to pay the mortgages on some of the farms and, the farmers here, owe to the banks." He is often misquoted,[citation needed] as on Farm Aid's official website, as saying "Wouldn't it be great if we did something for our own farmers right here in America?"

Although his comments were heavily criticised, they inspired fellow musicians Willie Nelson, John Mellencamp and Neil Young to organize the Farm Aid benefit concert to raise money for and help family farmers in the United States. The first concert was held on September 22, 1985, at the Memorial Stadium in Champaign, Illinois, before a crowd of 80,000 people.[1] Performers included Bob Dylan, Billy Joel, B.B. King, Loretta Lynn, Roy Orbison, and Tom Petty, among others,[2] and raised over $9 million for U.S. family farmers.[3]

In 2022, Farm Aid sought national recognition for the effort to encourage Americans to buy domestic beef.[4]

Structure

[edit]Willie and the other founders had originally thought that they could have one concert and the problem would be solved, but they admitted that the challenges facing family farmers were more complex than anyone realized.[5] As a result, decades after the first show, Farm Aid, under the direction of Carolyn Mugar, has been working to increase awareness of the importance of family farms, and puts on an annual concert of country, blues and rock music with a variety of music artists. The board of directors includes Nelson, Mellencamp, Young, and Dave Matthews, as well as David Anderson, Joel Katz, Lana Nelson, Mark Rothbaum, and Evelyn Shriver.[6] On April 8, 2021, it was announced that Annie Nelson and Margo Price joined as board members.[7] Board member Paul English, who was Willie Nelson's longtime drummer, died in February 2020.[8]

Service

[edit]The organization operates an emergency hotline that offers farmers resources and advice about challenges they're experiencing. Early on, Nelson and Mellencamp brought family farmers before Congress to testify about the state of family farming in America. Congress subsequently passed the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987 to help save family farms from foreclosure. Farm Aid also operates a disaster fund to help farmers who lose their belongings and crops through natural disasters, such as the victims of Hurricane Katrina[9] and massive flooding in 2019.[10] The funds raised are used to pay the farmer's expenses and provide food, legal and financial help, and psychological assistance.[11]

List of concerts

[edit]Board of directors

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Daniel Durchholz, Gary Graff. Neil Young: Long May You Run. Voyageur Press, 2010. p. 134.

- ^ "Past Concerts – Farm Aid". Archived from the original on May 23, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- ^ "Farm Aid 1985 – Champaign, IL". The Concert Stage. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ "Willie Nelson's Farm Aid wants you to know your "Made in USA" beef may have been raised in Brazil". CBS News.

- ^ "Listen Up, Good Food Movement!". Farm Aid. 2015-05-20. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- ^ "Farm Aid Board and Staff".

- ^ "Margo Price and Annie Nelson Join Farm Aid Board of Directors". Rolling Stone. 8 April 2021.

- ^ "Paul English, Willie Nelson's Longtime Drummer, Dead at 87". Rolling Stone. February 12, 2020.

- ^ "Farm Aid: Saving the Family Farm". Hidden Kitchens. National Public Radio. November 23, 2006. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ^ "'It Just Blows Your Mind': Midwest Farmers Suffer After Floods". www.governing.com. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 2020-03-02.

- ^ "Tornadoes Devastate Southern Farmers – You Can Help". Farm Aid. Willie Nelson.com. May 2, 2011. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011.

- ^ "Farm Aid 2012 Ticket Information". Farm Aid. Farm Aid.com. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ "The Farm Aid 2012 Lineup". Farm Aid. Farm Aid.com. Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ "The Farm Aid 2013 Lineup". Farm Aid. Farm Aid.com. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ "The Farm Aid 2014 Lineup". Farm Aid. Farm Aid.com. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ^ "The Farm Aid 2015 Lineup". Farm Aid. Farm Aid.com. Retrieved August 11, 2015.

- ^ "The Farm Aid Lineup". Farm Aid. FarmAid.com. Retrieved September 19, 2016.

- ^ "The Farm Aid 2017 Lineup". Farm Aid. Farm Aid.com. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ "The Farm Aid Lineup". Farm Aid. Retrieved 2019-09-25.

- ^ "Watch 'At Home with Farm Aid' on Saturday, April 11". Farm Aid. April 8, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Duffy, Thom (2023-09-24). "Bob Dylan Surprises Crowd at Willie Nelson's 2023 Farm Aid Festival in Indiana". Billboard. Retrieved 2023-09-24.

- ^ Mueller, Chris. "Bob Dylan joins lineup for Farm Aid 40: Here's what to know about the one-day music festival". St. Cloud Times. Retrieved 2025-10-13.

External links

[edit]Farm Aid

View on GrokipediaFarm Aid is a nonprofit organization founded in 1985 by musicians Willie Nelson, Neil Young, and John Mellencamp to raise funds and awareness for American family farmers confronting economic distress, including high debt, falling commodity prices, and land foreclosures during the 1980s farm crisis.[1][2] The inaugural concert, held on September 22, 1985, in Champaign, Illinois, drew 80,000 attendees and generated $7 million, inspired by Bob Dylan's onstage remark at Live Aid questioning aid for African famine versus domestic farmers.[2] Since then, annual events featuring prominent artists have collectively raised over $85 million, which Farm Aid allocates through grants to nonprofits supporting family farm viability, disaster relief, and advocacy for policies favoring small-scale operations over industrial consolidation.[1][2] Key achievements include influencing the 1987 Agricultural Credit Act, which provided debt restructuring and averted thousands of farm bankruptcies, alongside ongoing efforts to promote sustainable practices and resist corporate dominance in seed and food systems.[2] However, the initiative has drawn criticism from segments of the farming community for its vocal opposition to genetically modified organisms and large agribusiness, with some producers arguing that such stances alienate conventional operators and fail to address root economic pressures like market volatility and regulatory burdens, contributing to persistent declines in family farm numbers despite decades of fundraising.[3][4]

Origins in the 1980s Farm Crisis

Economic and Policy Context of the Crisis

The 1980s farm crisis stemmed from a confluence of tight monetary policy and expanding credit in the preceding decade, which fueled speculative land purchases and debt accumulation among farmers. In response to double-digit inflation, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates sharply, with the prime rate averaging 19 percent in 1981 and reaching peaks that made variable-rate loans unsustainable for agricultural borrowers.[5] Low rates in the 1970s had driven farmland values upward, prompting farmers to leverage equity for expansions, resulting in total U.S. farm debt climbing to approximately $191 billion by 1983, with debt-to-asset ratios exceeding 20 percent in key regions.[6][7] This leverage amplified vulnerability when rates inverted, turning asset appreciation into rapid deleveraging as fixed production costs outpaced revenue. Trade disruptions exacerbated the imbalance between supply and demand for U.S. grains. President Carter's January 1980 embargo on grain sales to the Soviet Union, in retaliation for the invasion of Afghanistan, canceled contracts for 17 million metric tons of corn, wheat, and soybeans, representing a significant share of U.S. exports and depressing commodity prices by redirecting surplus to domestic markets already facing overproduction.[8] Exports, which had surged to record levels in the late 1970s due to global shortages, contracted sharply, with grain prices falling amid competition from producers in countries employing heavy subsidies, such as the European Economic Community's Common Agricultural Policy, which flooded markets with low-cost alternatives.[9] This external shock compounded internal dynamics, as U.S. farmers had expanded acreage anticipating sustained foreign demand that failed to materialize. Federal agricultural policies, including the Agriculture and Food Act of 1981, prioritized production incentives through target price supports and non-recourse loan rates set above market levels for key crops like wheat and corn, encouraging continued planting without mechanisms to curb surpluses or align with export realities.[10] These loan rates, intended as safety nets, effectively subsidized overproduction, leading to government stockpiles and deficiency payments that ballooned from projected $11 billion to $63 billion over the bill's term, while failing to address underlying demand shortfalls or high input costs.[10] The absence of robust acreage reduction requirements, unlike prior decades, perpetuated a cycle of excess supply that eroded farmgate prices. The crisis culminated in widespread financial distress, with farm bankruptcies reaching a peak rate of 23.05 per 10,000 farms in 1987—the highest recorded—though filings exceeded 4,000 annually by 1985 in the hardest-hit Midwest states, forcing liquidations and foreclosures on roughly 300,000 operations by decade's end.[11] Rural banks, heavily exposed to agricultural loans, suffered accordingly, with nearly 200 agricultural institutions failing between 1985 and 1987, primarily in production-dependent regions, as nonperforming loans triggered systemic liquidity strains absent modern regulatory buffers.[12] These outcomes reflected causal chains from policy-induced expansions colliding with monetary tightening and trade barriers, rather than isolated exogenous events.Founding of Farm Aid and First Concert

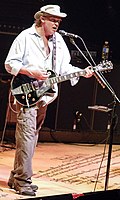

Willie Nelson conceived Farm Aid in 1985 upon encountering direct appeals from distressed farmers at tour stops in the Midwest, prompting him to address the acute threats of farm foreclosures and debt burdens through a dedicated benefit event.[13] He collaborated with fellow musicians Neil Young and John Mellencamp to rapidly organize the inaugural concert, scheduled for September 22, 1985, at Memorial Stadium in Champaign, Illinois, leveraging their platforms to amplify farmer concerns without reliance on government intervention.[1] The one-day event attracted 80,000 attendees and showcased over 40 performers, including Bob Dylan and Billy Joel, generating initial proceeds of approximately $9 million earmarked for family farm support.[14] [15] By 1986, Farm Aid had channeled $40,000 from its Illinois allocation—part of a $60,000 commitment—to approximately 140 farm families via cash disbursements for immediate crisis relief, such as covering essential expenses amid financial distress.[16] This launch established Farm Aid as a nonprofit entity focused on delivering targeted emergency aid, including financial counseling and resource provision, to preserve independent family operations imperiled by economic pressures rather than structural agricultural shifts.[17] The initiative prioritized on-the-ground responses to foreclosure risks, drawing from organizers' firsthand insights into farmers' predicaments to inform aid distribution logistics.[18]Organizational Governance

Board of Directors and Key Figures

Farm Aid's Board of Directors comprises musicians, family members of founder Willie Nelson, and longtime associates who guide the organization's strategic direction, including grant approvals, event curation, and advocacy priorities. Established with the founding concert in 1985, the board has expanded to include approximately eight to eleven members, depending on affiliations noted in filings, with Willie Nelson serving as president and chairman.[19][20] The board's composition emphasizes artistic figures aligned with anti-corporate farming stances, influencing a focus on sustainable, family-centered agriculture over large-scale industrial models.[1] The core founders—Willie Nelson, Neil Young, and John Mellencamp—initiated Farm Aid amid the 1980s farm crisis, leveraging their platforms to raise funds and awareness for struggling family farmers. Nelson, a country music legend born in 1933, has advocated for rural issues through his music and activism, including criticisms of agribusiness consolidation.[1] Young, a rock musician known for environmental causes and public opposition to genetically modified crops, brings a perspective favoring ecological farming practices.[21] Mellencamp, a heartland rock artist from Indiana, emphasizes themes of rural American resilience, reflecting populist concerns about economic pressures on small farms.[22] These founders perform at annual events and shape programming to highlight independent agriculture. Additional board members include Dave Matthews, who joined in 2001 and contributes through performances with his band, and Margo Price, added in 2021 as a country artist critical of corporate dominance in food systems.[1] Family members Annie Nelson and Lana Nelson, daughters of Willie Nelson, joined around 2021; Annie as a humanitarian focused on farmer advocacy, and Lana handling administrative roles like secretary.[19][23] Mark Rothbaum, Nelson's longtime manager, provides operational expertise.[24] This mix of celebrities and insiders facilitates high-profile fundraising while directing resources toward grants for family farm resilience, though their artistic backgrounds may prioritize visibility over specialized policy analysis.[25]| Board Member | Role/Background | Year Joined (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|

| Willie Nelson | President/Chairman; Country musician and farm advocate | Founder (1985)[26] |

| Neil Young | Rock musician; Environmental and anti-GMO advocate | Founder (1985)[1] |

| John Mellencamp | Singer-songwriter; Rural America themes | Founder (1985)[1] |

| Dave Matthews | Musician; Performs at events | 2001[1] |

| Margo Price | Country artist; Anti-corporate farming views | 2021[19] |

| Annie Nelson | Humanitarian; Family farm supporter | 2021[27] |

| Lana Nelson | Administrative support; Secretary | Pre-2021[20] |

| Mark Rothbaum | Manager; Operational guidance | Longstanding[24] |