Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

IMPLY gate

View on Wikipedia| Input A B |

Output A → B | |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

The IMPLY gate is a digital logic gate that implements a logical conditional.

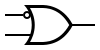

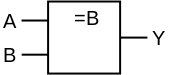

Symbols

[edit]IMPLY can be denoted in algebraic expressions with the logic symbol right-facing arrow (→). Logically, it is equivalent to material implication, and the logical expression ¬A v B.

There are two symbols for IMPLY gates: the traditional symbol and the IEEE symbol. For more information see Logic gate symbols.

|

| |

| Traditional IMPLY Symbol | IEEE IMPLY Symbol |

Functional completeness

[edit]While the Implication gate is not functionally complete by itself, it is in conjunction with the constant 0 source. This can be shown via the following:

Thus, since the implication gate with the addition of the constant 0 source can create both the NOT gate and the OR gate, it can create the NOR gate, which is a universal gate.

See also

[edit]- NIMPLY gate

- AND gate

- NOT gate

- NAND gate

- NOR gate

- XOR gate

- XNOR gate

- Boolean algebra (logic)

- Logic gates

IMPLY gate

View on Grokipedia| A | B | A → B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

Definition and Operation

Logical Definition

The IMPLY gate is a binary digital logic gate that realizes material implication, a core operation in propositional logic. Given two inputs, A (the antecedent) and B (the consequent), the gate's output is true if A is false or B is true, and false exclusively when A is true and B is false. This truth-functional behavior ensures the output evaluates to true in three out of four possible input combinations, reflecting the minimal conditions under which a conditional statement holds in classical logic.[3] In propositional logic, the IMPLY gate functions as a primitive connective that models the indicative conditional ("if A, then B"), but it diverges from everyday notions of implication by prioritizing strict truth-value dependencies over causal or probabilistic interpretations. This distinction underscores its role in formal systems, where it enables the construction of complex logical expressions without assuming real-world entailment.[3] Material implication originated in ancient Stoic logic, attributed to Philo of Megara in the 3rd century BCE, but received its modern formulation in the late 19th century through Gottlob Frege's Begriffsschrift, which systematized propositional connectives including implication. It was further refined in early 20th-century works like Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead's Principia Mathematica (1910–1913), integrating it into axiomatic logic. The operation's adaptation to digital gates occurred in the mid-20th century via Boolean algebra, notably through Claude Shannon's 1938 master's thesis, "A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits," which showed how Boolean algebra could be used to analyze and simplify relay and switching circuits, establishing the basis for digital logic design.[3][4] This logical foundation is prerequisite for analyzing the IMPLY gate's input-output mappings and its practical realizations in computational systems.Truth Table

The truth table for the IMPLY gate provides a complete mapping of all possible binary input combinations to their corresponding output, using the standard digital logic convention where 0 represents false and 1 represents true.[5] This table illustrates the gate's behavior as a logical conditional, where the output is 1 (true) unless the first input A is 1 and the second input B is 0.[6]| A | B | A → B |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |