Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Logic gate

View on Wikipedia

A logic gate is a device that performs a Boolean function, a logical operation performed on one or more binary inputs that produces a single binary output. Depending on the context, the term may refer to an ideal logic gate, one that has, for instance, zero rise time and unlimited fan-out, or it may refer to a non-ideal physical device[1] (see ideal and real op-amps for comparison).

The primary way of building logic gates uses diodes or transistors acting as electronic switches. Today, most logic gates are made from MOSFETs (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors).[2] They can also be constructed using vacuum tubes, electromagnetic relays with relay logic, fluidic logic, pneumatic logic, optics, molecules, acoustics,[3] or even mechanical or thermal[4] elements.

Logic gates can be cascaded in the same way that Boolean functions can be composed, allowing the construction of a physical model of all of Boolean logic, and therefore, all of the algorithms and mathematics that can be described with Boolean logic. Logic circuits include such devices as multiplexers, registers, arithmetic logic units (ALUs), and computer memory, all the way up through complete microprocessors,[5] which may contain more than 100 million logic gates.

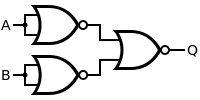

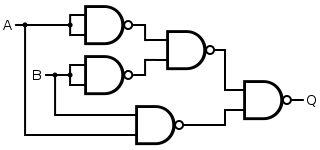

Compound logic gates AND-OR-invert (AOI) and OR-AND-invert (OAI) are often employed in circuit design because their construction using MOSFETs is simpler and more efficient than the sum of the individual gates.[6]

History and development

[edit]The binary number system was refined by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (published in 1705), influenced by the ancient I Ching's binary system.[7][8] Leibniz established that using the binary system combined the principles of arithmetic and logic.

The analytical engine devised by Charles Babbage in 1837 used mechanical logic gates based on gears.[9]

In an 1886 letter, Charles Sanders Peirce described how logical operations could be carried out by electrical switching circuits.[10] Early Electromechanical computers were constructed from switches and relay logic rather than the later innovations of vacuum tubes (thermionic valves) or transistors (from which later electronic computers were constructed). Ludwig Wittgenstein introduced a version of the 16-row truth table as proposition 5.101 of Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921). Walther Bothe, inventor of the coincidence circuit,[11] got part of the 1954 Nobel Prize in physics, for the first modern electronic AND gate in 1924. Konrad Zuse designed and built electromechanical logic gates for his computer Z1 (from 1935 to 1938).

From 1934 to 1936, NEC engineer Akira Nakashima, Claude Shannon and Victor Shestakov introduced switching circuit theory in a series of papers showing that two-valued Boolean algebra, which they discovered independently, can describe the operation of switching circuits.[12][13][14][15] Using this property of electrical switches to implement logic is the fundamental concept that underlies all electronic digital computers. Switching circuit theory became the foundation of digital circuit design, as it became widely known in the electrical engineering community during and after World War II, with theoretical rigor superseding the ad hoc methods that had prevailed previously.[15]

In 1948, Bardeen and Brattain patented an insulated-gate transistor (IGFET) with an inversion layer. Their concept forms the basis of CMOS technology today.[16] In 1957, Frosch and Derick were able to manufacture PMOS and NMOS planar gates.[17] Later a team at Bell Labs demonstrated a working MOS with PMOS and NMOS gates.[18] Both types were later combined and adapted into complementary MOS (CMOS) logic by Chih-Tang Sah and Frank Wanlass at Fairchild Semiconductor in 1963.[19]

Symbols

[edit]

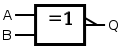

There are two sets of symbols for elementary logic gates in common use, both defined in ANSI/IEEE Std 91-1984 and its supplement ANSI/IEEE Std 91a-1991. The "distinctive shape" set, based on traditional schematics, is used for simple drawings and derives from United States Military Standard MIL-STD-806 of the 1950s and 1960s.[20] It is sometimes unofficially described as "military", reflecting its origin. The "rectangular shape" set, based on ANSI Y32.14 and other early industry standards as later refined by IEEE and IEC, has rectangular outlines for all types of gate and allows representation of a much wider range of devices than is possible with the traditional symbols.[21] The IEC standard, IEC 60617-12, has been adopted by other standards, such as EN 60617-12:1999 in Europe, BS EN 60617-12:1999 in the United Kingdom, and DIN EN 60617-12:1998 in Germany.

The mutual goal of IEEE Std 91-1984 and IEC 617-12 was to provide a uniform method of describing the complex logic functions of digital circuits with schematic symbols. These functions were more complex than simple AND and OR gates. They could be medium-scale circuits such as a 4-bit counter to a large-scale circuit such as a microprocessor.

IEC 617-12 and its renumbered successor IEC 60617-12 do not explicitly show the "distinctive shape" symbols, but do not prohibit them.[21] These are, however, shown in ANSI/IEEE Std 91 (and 91a) with this note: "The distinctive-shape symbol is, according to IEC Publication 617, Part 12, not preferred, but is not considered to be in contradiction to that standard." IEC 60617-12 correspondingly contains the note (Section 2.1) "Although non-preferred, the use of other symbols recognized by official national standards, that is distinctive shapes in place of symbols [list of basic gates], shall not be considered to be in contradiction with this standard. Usage of these other symbols in combination to form complex symbols (for example, use as embedded symbols) is discouraged." This compromise was reached between the respective IEEE and IEC working groups to permit the IEEE and IEC standards to be in mutual compliance with one another.

In the 1980s, schematics were the predominant method to design both circuit boards and custom ICs known as gate arrays. Today custom ICs and the field-programmable gate array are typically designed with Hardware Description Languages (HDL) such as Verilog or VHDL.

| Type | Distinctive shape (IEEE Std 91/91a-1991) |

Rectangular shape (IEEE Std 91/91a-1991) (IEC 60617-12:1997) |

Boolean algebra between A and B | Truth table | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-input gates | ||||||||||||||||||||||

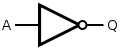

| Buffer |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| NOT (inverter) |

or |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| In electronics a NOT gate is more commonly called an inverter. The circle on the symbol is called a bubble and is used in logic diagrams to indicate a logic negation between the external logic state and the internal logic state (1 to 0 or vice versa). On a circuit diagram it must be accompanied by a statement asserting that the positive logic convention or negative logic convention is being used (high voltage level = 1 or low voltage level = 1, respectively). The wedge is used in circuit diagrams to directly indicate an active-low (low voltage level = 1) input or output without requiring a uniform convention throughout the circuit diagram. This is called Direct Polarity Indication. See IEEE Std 91/91A and IEC 60617-12. Both the bubble and the wedge can be used on distinctive-shape and rectangular-shape symbols on circuit diagrams, depending on the logic convention used. On pure logic diagrams, only the bubble is meaningful. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

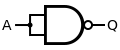

| Conjunction and disjunction | ||||||||||||||||||||||

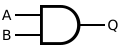

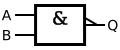

| AND | or |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

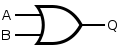

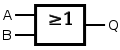

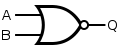

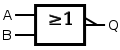

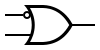

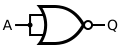

| OR | or |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative denial and joint denial | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| NAND | or |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| NOR |

|

|

or |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Exclusive or and biconditional | ||||||||||||||||||||||

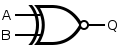

| XOR |

|

|

or |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| The output of a two input exclusive-OR is true only when the two input values are different, and false if they are equal, regardless of the value. If there are more than two inputs, the output of the distinctive-shape symbol is undefined. The output of the rectangular-shaped symbol is true if the number of true inputs is exactly one or exactly the number following the "=" in the qualifying symbol. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| XNOR |

|

|

or |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Implication and Nonimplication | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| IMPLY[22][23] |

|

or |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| NIMPLY | or |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| IMPLY and NIMPLY are not commutative, meaning that changing the order of the operands may change the result. For instance, is false, but is true; likewise, is true, but is false. | ||||||||||||||||||||||

De Morgan equivalent symbols

[edit]By use of De Morgan's laws, an AND function is identical to an OR function with negated inputs and outputs. Likewise, an OR function is identical to an AND function with negated inputs and outputs. A NAND gate is equivalent to an OR gate with negated inputs, and a NOR gate is equivalent to an AND gate with negated inputs.

This leads to an alternative set of symbols for basic gates that use the opposite core symbol (AND or OR) but with the inputs and outputs negated. Use of these alternative symbols can make logic circuit diagrams much clearer and help to show accidental connection of an active high output to an active low input or vice versa. Any connection that has logic negations at both ends can be replaced by a negationless connection and a suitable change of gate or vice versa. Any connection that has a negation at one end and no negation at the other can be made easier to interpret by instead using the De Morgan equivalent symbol at either of the two ends. When negation or polarity indicators on both ends of a connection match, there is no logic negation in that path (effectively, bubbles "cancel"), making it easier to follow logic states from one symbol to the next. This is commonly seen in real logic diagrams – thus the reader must not get into the habit of associating the shapes exclusively as OR or AND shapes, but also take into account the bubbles at both inputs and outputs in order to determine the "true" logic function indicated.

A De Morgan symbol can show more clearly a gate's primary logical purpose and the polarity of its nodes that are considered in the "signaled" (active, on) state. Consider the simplified case where a two-input NAND gate is used to drive a motor when either of its inputs are brought low by a switch. The "signaled" state (motor on) occurs when either one OR the other switch is on. Unlike a regular NAND symbol, which suggests AND logic, the De Morgan version, a two negative-input OR gate, correctly shows that OR is of interest. The regular NAND symbol has a bubble at the output and none at the inputs (the opposite of the states that will turn the motor on), but the De Morgan symbol shows both inputs and output in the polarity that will drive the motor.

De Morgan's theorem is most commonly used to implement logic gates as combinations of only NAND gates, or as combinations of only NOR gates, for economic reasons.

Truth tables

[edit]Output comparison of various logic gates:

| Input | Output | |

| A | Buffer | Inverter |

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Input | Output | ||||||||

| A | B | AND | NAND | OR | NOR | XOR | XNOR | IMPLY | NIMPLY |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Universal logic gates

[edit]Charles Sanders Peirce (during 1880–1881) showed that NOR gates alone (or alternatively NAND gates alone) can be used to reproduce the functions of all the other logic gates, but his work on it was unpublished until 1933.[24] The first published proof was by Henry M. Sheffer in 1913, so the NAND logical operation is sometimes called Sheffer stroke; the logical NOR is sometimes called Peirce's arrow.[25] Consequently, these gates are sometimes called universal logic gates.[26]

| type | NAND construction | NOR construction |

|---|---|---|

| NOT |

|

|

| AND |

|

|

| NAND |

|

|

| OR |

|

|

| NOR |

|

|

| XOR |

|

|

| XNOR |

|

|

| IMPLY |

|

|

| NIMPLY |

Data storage and sequential logic

[edit]

Logic gates can also be used to hold a state, allowing data storage. A storage element can be constructed by connecting several gates in a "latch" circuit. Latching circuitry is used in static random-access memory. More complicated designs that use clock signals and that change only on a rising or falling edge of the clock are called edge-triggered "flip-flops". Formally, a flip-flop is called a bistable circuit, because it has two stable states which it can maintain indefinitely. The combination of multiple flip-flops in parallel, used to store a multiple-bit value, is known as a register. When using any of these gate setups the overall system has memory; it is then called a sequential logic system since its output can be influenced by its previous state(s), i.e. by the sequence of input states. In contrast, the output from combinational logic is purely a combination of its present inputs, unaffected by the previous input and output states.

These logic circuits are used in computer memory. They vary in performance, based on factors of speed, complexity, and reliability of storage, and many different types of designs are used based on the application.

Manufacturing

[edit]Electronic gates

[edit]A functionally complete logic system may be composed of relays, valves (vacuum tubes), or transistors.

Electronic logic gates differ significantly from their relay-and-switch equivalents. They are much faster, consume much less power, and are much smaller (all by a factor of a million or more in most cases). Also, there is a fundamental structural difference. The switch circuit creates a continuous metallic path for current to flow (in either direction) between its input and its output. The semiconductor logic gate, on the other hand, acts as a high-gain voltage amplifier, which sinks a tiny current at its input and produces a low-impedance voltage at its output. It is not possible for current to flow between the output and the input of a semiconductor logic gate.

For small-scale logic, designers now use prefabricated logic gates from families of devices such as the TTL 7400 series by Texas Instruments, the CMOS 4000 series by RCA, and their more recent descendants. Increasingly, these fixed-function logic gates are being replaced by programmable logic devices, which allow designers to pack many mixed logic gates into a single integrated circuit. The field-programmable nature of programmable logic devices such as FPGAs has reduced the "hard" property of hardware; it is now possible to change the logic design of a hardware system by reprogramming some of its components, thus allowing the features or function of a hardware implementation of a logic system to be changed.

An important advantage of standardized integrated circuit logic families, such as the 7400 and 4000 families, is that they can be cascaded. This means that the output of one gate can be wired to the inputs of one or several other gates, and so on. Systems with varying degrees of complexity can be built without great concern of the designer for the internal workings of the gates, provided the limitations of each integrated circuit are considered.

The output of one gate can only drive a finite number of inputs to other gates, a number called the "fan-out limit". Also, there is always a delay, called the "propagation delay", from a change in input of a gate to the corresponding change in its output. When gates are cascaded, the total propagation delay is approximately the sum of the individual delays, an effect which can become a problem in high-speed synchronous circuits. Additional delay can be caused when many inputs are connected to an output, due to the distributed capacitance of all the inputs and wiring and the finite amount of current that each output can provide.

Logic families

[edit]There are several logic families with different characteristics (power consumption, speed, cost, size) such as: RDL (resistor–diode logic), RTL (resistor-transistor logic), DTL (diode–transistor logic), TTL (transistor–transistor logic) and CMOS. There are also sub-variants, e.g. standard CMOS logic vs. advanced types using still CMOS technology, but with some optimizations for avoiding loss of speed due to slower PMOS transistors.

The simplest family of logic gates uses bipolar transistors, and is called resistor–transistor logic (RTL). Unlike simple diode logic gates (which do not have a gain element), RTL gates can be cascaded indefinitely to produce more complex logic functions. RTL gates were used in early integrated circuits. For higher speed and better density, the resistors used in RTL were replaced by diodes resulting in diode–transistor logic (DTL). Transistor–transistor logic (TTL) then supplanted DTL.

As integrated circuits became more complex, bipolar transistors were replaced with smaller field-effect transistors (MOSFETs); see PMOS and NMOS. To reduce power consumption still further, most contemporary chip implementations of digital systems now use CMOS logic. CMOS uses complementary (both n-channel and p-channel) MOSFET devices to achieve a high speed with low power dissipation.

Other types of logic gates include, but are not limited to:[27]

| Logic family | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Diode logic | DL | |

| Tunnel diode logic | TDL | Exactly the same as diode logic but can perform at a higher speed.[failed verification] |

| Neon logic | NL | Uses neon bulbs or 3-element neon trigger tubes to perform logic. |

| Core diode logic | CDL | Performed by semiconductor diodes and small ferrite toroidal cores for moderate speed and moderate power level. |

| 4Layer Device Logic | 4LDL | Uses thyristors and SCRs to perform logic operations where high current and or high voltages are required. |

| Direct-coupled transistor logic | DCTL | Uses transistors switching between saturated and cutoff states to perform logic. The transistors require carefully controlled parameters. Economical because few other components are needed, but tends to be susceptible to noise because of the lower voltage levels employed. Often considered to be the father to modern TTL logic. |

| Metal–oxide–semiconductor logic | MOS | Uses MOSFETs (metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors), the basis for most modern logic gates. The MOS logic family includes PMOS logic, NMOS logic, complementary MOS (CMOS), and BiCMOS (bipolar CMOS). |

| Current-mode logic | CML | Uses transistors to perform logic but biasing is from constant current sources to prevent saturation and allow extremely fast switching. Has high noise immunity despite fairly low logic levels. |

| Quantum-dot cellular automata | QCA | Uses tunnelable q-bits for synthesizing the binary logic bits. The electrostatic repulsive force in between two electrons in the quantum dots assigns the electron configurations (that defines state 1 or state 0) under the suitably driven polarizations. This is a transistorless, currentless, junctionless binary logic synthesis technique allowing it to have very fast operation speeds. |

| Ferroelectric FET | FeFET | FeFET transistors can retain their state to speed recovery in case of a power loss.[28] |

Three-state logic gates

[edit]

A three-state logic gate is a type of logic gate that can have three different outputs: high (H), low (L) and high-impedance (Z). The high-impedance state plays no role in the logic, which is strictly binary. These devices are used on buses of the CPU to allow multiple chips to send data. A group of three-state outputs driving a line with a suitable control circuit is basically equivalent to a multiplexer, which may be physically distributed over separate devices or plug-in cards.

In electronics, a high output would mean the output is sourcing current from the positive power terminal (positive voltage). A low output would mean the output is sinking current to the negative power terminal (zero voltage). High impedance would mean that the output is effectively disconnected from the circuit.

Non-electronic logic gates

[edit]Non-electronic implementations are varied, though few of them are used in practical applications. Many early electromechanical digital computers, such as the Harvard Mark I, were built from relay logic gates, using electro-mechanical relays. Logic gates can be made using pneumatic devices, such as the Sorteberg relay or mechanical logic gates, including on a molecular scale.[29] Various types of fundamental logic gates have been constructed using molecules (molecular logic gates), which are based on chemical inputs and spectroscopic outputs.[30] Logic gates have been made out of DNA (see DNA nanotechnology)[31] and used to create a computer called MAYA (see MAYA-II). Logic gates can be made from quantum mechanical effects, see quantum logic gate. Photonic logic gates use nonlinear optical effects.

In principle any method that leads to a gate that is functionally complete (for example, either a NOR or a NAND gate) can be used to make any kind of digital logic circuit. Note that the use of 3-state logic for bus systems is not needed, and can be replaced by digital multiplexers, which can be built using only simple logic gates (such as NAND gates, NOR gates, or AND and OR gates).

See also

[edit]- And-inverter graph

- Boolean algebra topics

- Boolean function

- Depletion-load NMOS logic

- Digital circuit

- Electronic symbol

- Espresso heuristic logic minimizer

- Emitter-coupled logic

- Fan-out

- Field-programmable gate array (FPGA)

- Flip-flop (electronics)

- Functional completeness

- Integrated injection logic

- Karnaugh map

- Combinational logic

- List of 4000 series integrated circuits

- List of 7400 series integrated circuits

- Logic family

- Logic level

- Logical graph

- Magnetic logic

- NMOS logic

- Parametron

- Processor design

- Programmable logic controller (PLC)

- Programmable logic device (PLD)

- Propositional calculus

- Race hazard

- Reversible computing

- Superconducting computing

- Truth table

- Unconventional computing

References

[edit]- ^ Jaeger (1997). Microelectronic Circuit Design. McGraw-Hill. pp. 226–233. ISBN 0-07-032482-4.

- ^ Kanellos, Michael (2003-02-11). "Moore's Law to roll on for another decade". CNET. From Integrated circuit

- ^ Zhang, Ting; Cheng, Ying; Guo, Jian-Zhong; Xu, Jian-yi; Liu, Xiao-jun (2015), "Acoustic logic gates and Boolean operation based on self-collimating acoustic beams", Applied Physics Letters, 106 (11) 113503, Bibcode:2015ApPhL.106k3503Z, doi:10.1063/1.4915338, retrieved 2024-08-17

- ^ Wang, Lei; Li, Baowen (2007). "Thermal Logic Gates: Computation with Phonons". Physical Review Letters. 99 (17) 177208. arXiv:0709.0032. Bibcode:2007PhRvL..99q7208W. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.177208. PMID 17995368. S2CID 10934270.

- ^ Deschamps, Jean-Pierre; Valderrama, Elena; Terés, Lluís (2016-10-12). Digital Systems: From Logic Gates to Processors. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-41198-9.

- ^ Tinder, Richard F. (2000). Engineering digital design (2nd ed.). Academic Press. pp. 317–319. ISBN 0-12-691295-5.

- ^ Nylan, Michael (2001). The Five "Confucian" Classics. Yale University Press. pp. 204–206. ISBN 978-0-300-08185-5. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ Perkins, Franklin (2004). "Exchange with China". Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-521-83024-9.

... one of the traditional orderings of the hexagrams, the xiantian tu ordering made by Shao Yong, was, with a few modifications, the same order found in Leibniz's binary arithmetic.

- ^ Julio Sanchez; Maria P. Canton (2017-12-19). Embedded Systems Circuits and Programming. CRC Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-4398-7931-3.

- ^ Peirce, C. S., "Letter, Peirce to A. Marquand", dated 1886, Writings of Charles S. Peirce, v. 5, 1993, pp. 420–423. See Burks, Arthur W. (1978). "Review: Charles S. Peirce, The new elements of mathematics". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 84 (5): 913–918 [917]. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1978-14533-9.

- ^ Luisa Bonolis; Walther Bothe and Bruno Rossi: The birth and development of coincidence methods in cosmic-ray physics. Am. J. Phys. 1 November 2011; 79 (11): 1133–1150.

- ^ Yamada, Akihiko (2004). "History of Research on Switching Theory in Japan". IEEJ Transactions on Fundamentals and Materials. 124 (8). Institute of Electrical Engineers of Japan: 720–726. Bibcode:2004IJTFM.124..720Y. doi:10.1541/ieejfms.124.720.

- ^ "Switching Theory/Relay Circuit Network Theory/Theory of Logical Mathematics". IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan.

- ^ Stanković, Radomir S.; Astola, Jaakko T.; Karpovsky, Mark G. (2007). Some Historical Remarks on Switching Theory. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.66.1248.

- ^ a b Stanković, Radomir S. [in German]; Astola, Jaakko Tapio [in Finnish], eds. (2008). Reprints from the Early Days of Information Sciences: TICSP Series On the Contributions of Akira Nakashima to Switching Theory (PDF). Tampere International Center for Signal Processing (TICSP) Series. Vol. 40. Tampere University of Technology, Tampere, Finland. ISBN 978-952-15-1980-2. ISSN 1456-2774. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-03-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (3+207+1 pages) 10:00 min - ^ Howard R. Duff (2001). "John Bardeen and transistor physics". AIP Conference Proceedings. Vol. 550. pp. 3–32. doi:10.1063/1.1354371.

- ^ Frosch, C. J.; Derick, L (1957). "Surface Protection and Selective Masking during Diffusion in Silicon". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 104 (9): 547. doi:10.1149/1.2428650.

- ^ Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-540-34258-8.

- ^ "1963: Complementary MOS Circuit Configuration is Invented". Computer History Museum. Retrieved 2019-07-06.

- ^ "Graphical Symbols for Logic Diagrams". ASSIST Quick Search. Defense Logistics Agency. MIL-STD-806. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ^ a b "Overview of IEEE Standard 91-1984 Explanation of Logic Symbols" (PDF). Texas Instruments Semiconductor Group. 1996. SDYZ001A.

- ^ Jyoti Garg; Aishita Verma; Subodh Wairya. "Memristor Emulator Circuits an Emerging Technology with Applications". In Brijesh Mishra; Manish Tiwari (eds.). VLSI, Microwave and Wireless Technologies. p. 476.

- ^ Hanawalt, Barbara (2004-08-05). Cellular Computing. Oxford University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-803537-4.

- ^ Peirce, C. S. (manuscript winter of 1880–1881), "A Boolian Algebra with One Constant", published 1933 in Collected Papers v. 4, paragraphs 12–20. Reprinted 1989 in Writings of Charles S. Peirce v. 4, pp. 218–221, Google [1]. See Roberts, Don D. (2009). "7.12 The Graphical Analysis of Propositions". The Existential Graphs of Charles S. Peirce. De Gruyter. p. 131. ISBN 978-3-11022622-5.

- ^ Büning, Hans Kleine; Lettmann, Theodor (1999). Propositional logic: deduction and algorithms. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-521-63017-7.

- ^ Bird, John (2007). Engineering mathematics. Newnes. p. 532. ISBN 978-0-7506-8555-9.

- ^ Rowe, Jim. "Circuit Logic – Why and How". No. December 1966. Electronics Australia.

- ^ "Tapping into Non-Volatile Logic". 2021-04-21.

- ^ Merkle, Ralph C. (1993). "Two Types of Mechanical Reversible Logic". Xerox PARC.

- ^ Erbas-Cakmak, Sundus; Kolemen, Safacan; Sedgwick, Adam C.; Gunnlaugsson, Thorfinnur; James, Tony D.; Yoon, Juyoung; Akkaya, Engin U. (2018). "Molecular logic gates: the past, present and future". Chemical Society Reviews. 47 (7): 2228–2248. doi:10.1039/C7CS00491E. hdl:11693/50034. ISSN 0306-0012. PMID 29493684.

- ^ Stojanovic, Milan N.; Mitchell, Tiffany E.; Stefanovic, Darko (2002). "Deoxyribozyme-Based Logic Gates". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (14): 3555–3561. Bibcode:2002JAChS.124.3555S. doi:10.1021/ja016756v. PMID 11929243.

Further reading

[edit]- Bostock, Geoff (1988). Programmable logic devices: technology and applications. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-006611-3.

- Brown, Stephen D.; Francis, Robert J.; Rose, Jonathan; Vranesic, Zvonko G. (1992). Field Programmable Gate Arrays. Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-0-7923-9248-4.

External links

[edit] Media related to Logic gates at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Logic gates at Wikimedia Commons

Logic gate

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and principles

A logic gate is an idealized or physical electronic device that performs a Boolean function on one or more binary inputs, producing a single binary output.[2] These devices implement fundamental logical operations, such as conjunction (AND), disjunction (OR), and negation (NOT), serving as the basic units for processing binary signals in digital systems.[11] The principles of logic gates are rooted in binary logic, a two-valued system where inputs and outputs represent truth values—typically denoted as true (1 or high voltage) or false (0 or low voltage).[11] Each gate operates deterministically, computing its output based solely on the current input combination, without memory of prior states.[2] In general, a logic gate realizes a Boolean function , where through are binary input variables (each 0 or 1), and the output is the result of applying the function to those inputs.[2] These gates form the foundational building blocks of digital circuits, interconnecting to construct more complex logical structures.[1] In computing and electronics, logic gates enable essential functions such as arithmetic operations, control signals, and data routing by combining into larger circuits that perform sophisticated tasks.[12] For instance, networks of gates can implement addition, decision-making, and information flow in processors and memory systems, underpinning the operation of modern digital devices.[13] This binary decision-making capability, derived from Boolean algebra, allows for the reliable manipulation of information in computational environments.[14]Basic logic gates

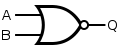

Basic logic gates form the foundational building blocks of digital circuits, performing fundamental Boolean operations on binary inputs to produce a single binary output. These gates operate on logic levels representing 0 (false or low) and 1 (true or high), and they are essential for implementing conditional logic in electronic systems. The primary basic gates include the AND, OR, NOT, NAND, NOR, XOR, and XNOR, each with distinct input/output behaviors that enable the construction of more complex functions. While most gates accept two or more inputs, the NOT gate is unique in requiring only one. The AND gate outputs a logic 1 only if all of its inputs are 1; otherwise, it outputs 0. It typically has a minimum of two inputs but can be extended to multiple inputs for broader conjunction operations. This gate performs a function analogous to multiplication in binary arithmetic, where the output represents the product of inputs. For example, in a security system, an AND gate can ensure that multiple sensors (such as a door lock and a keycard reader) must all detect valid conditions before granting access.[8][15][16] The OR gate outputs a logic 1 if at least one of its inputs is 1; it outputs 0 only if all inputs are 0. Like the AND gate, it supports a minimum of two inputs and can handle multiple inputs for disjunction logic. This inclusive OR function detects the presence of any true condition, differing from the exclusive variant (XOR) which requires exactly one true input. In applications such as alarm systems, an OR gate triggers an alert if any sensor detects an intrusion, like a door opening or glass breaking.[8][16][17] The NOT gate, also known as an inverter, takes a single input and outputs the logical complement: 1 if the input is 0, and 0 if the input is 1. With only one input, it serves as the basic negation operator in digital logic. It is fundamental for inverting signals, such as flipping a control bit to deactivate a previously active function in simple switching circuits.[8][16][1] The NAND gate is the inverted form of the AND gate, outputting 0 only if all inputs are 1, and 1 otherwise. It requires a minimum of two inputs and, like the AND, supports multi-input configurations. As a universal gate, NAND can implement any Boolean function when combined appropriately, making it versatile for compact circuit designs.[8][16] The NOR gate inverts the OR function, outputting 1 only if all inputs are 0, and 0 otherwise. It also has a minimum of two inputs and can be multi-input. NOR is similarly universal, capable of realizing all other logic functions, which contributes to its use in efficient implementations of complex logic.[8][16] The XOR gate outputs 1 if its inputs differ (one is 1 and the other is 0), and 0 if they are the same. It operates on exactly two inputs, as multi-input versions are typically constructed from pairs. XOR is key in applications like binary addition, where it generates the sum bit, and parity checking, where it detects an odd number of 1s in data for error detection.[8][16][17] The XNOR gate, or equivalence gate, inverts the XOR output, producing 1 if its two inputs are identical and 0 if they differ. It is used for equality comparisons, such as verifying matching bits in data validation processes.[8][16]Representation

Graphical symbols

Graphical symbols for logic gates provide a standardized visual language for representing digital circuits in schematics, allowing designers to abstract away physical implementations and focus on logical interconnections. These symbols emphasize input-output relationships and facilitate international communication in engineering documentation. The primary standards include the distinctive-shape symbols derived from earlier military specifications like MIL-STD-806B and the rectangular-outline symbols defined in ANSI/IEEE Std 91-1984, which is compatible with IEC 60617-12 for broader adoption.[18][19][20][21] Distinctive-shape symbols use unique geometric forms to intuitively convey gate functions, with inputs typically on the left and outputs on the right. The AND gate appears as a D-shaped enclosure (curved on the right), accepting multiple inputs that converge to a single output. The OR gate features a curved shape with pointed extensions on the input side, symbolizing addition-like behavior. The NOT gate is depicted as a right-pointing triangle with a small circle (bubble) at the output tip, indicating inversion. For multi-input versions, additional lines connect to the main body, such as three inputs joining the AND shape. These shapes, while mnemonic, have largely been supplanted by rectangular forms for compactness in complex diagrams.[20][19] In contrast, rectangular-outline symbols employ uniform boxes to promote consistency, with the gate's operation denoted by an internal label or qualifier. Under ANSI/IEEE Std 91-1984, the AND gate is a rectangle containing the ampersand (&), the OR gate uses ≥1, and the NOT gate includes a flag-like extension or the numeral 1 with negation. Multi-input notations leverage dependency symbols, such as subscripted G for ANDed inputs (e.g., G1, G2) or V for ORed inputs, placed near the rectangle to indicate grouping without drawing multiple lines. This approach supports hierarchical designs and is prevalent in modern integrated circuit schematics.[18][19] Variations exist across standards to accommodate regional or historical preferences. IEC 60617-12 favors rectangular shapes exclusively, aligning closely with IEEE but using flags for negation instead of bubbles in some cases. Older European styles, like DIN 40700, occasionally appear in legacy documentation with slightly altered curvatures. Bubble notation—a small open circle—universally denotes inversion or active-low signals, placed at inputs for complemented logic (e.g., active-low enable) or outputs for negated results (e.g., NAND as AND with output bubble). An alternative triangular polarity indicator specifies active-low without inversion in positive-logic contexts, enhancing precision in mixed-signal diagrams. These elements ensure symbols remain versatile for schematic abstraction and standardization.[20][18][19]Truth tables

Truth tables provide a tabular method to enumerate all possible input combinations for a logic gate and determine the corresponding output based on its logical function. For a gate with n binary inputs, the table consists of 2n rows, each representing a unique input combination, with columns dedicated to the input variables and the output. This exhaustive listing ensures complete coverage of the gate's behavior, using 0 to denote false and 1 to denote true. Intermediate columns may be included for complex expressions to break down the computation step by step.[22][9] The NOT gate, which inverts a single input, has the simplest truth table with two rows:| Input A | Output |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 |

| Input A | Input B | Output (A AND B) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Input A | Input B | Output (A OR B) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Input A | Input B | Output (A XOR B) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

Advanced Concepts

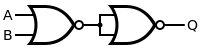

Universal logic gates

A universal logic gate is one that, by itself, can be used to construct any possible Boolean function, thereby forming a functionally complete set. The NAND and NOR gates qualify as universal because they inherently combine logical conjunction (AND) or disjunction (OR) with inversion (NOT), enabling the replication of all basic operations through appropriate interconnections.[25][26][27] The NAND gate's universality is demonstrated by its ability to implement NOT, AND, OR, and more complex functions like XOR using only NAND gates. To create a NOT gate, connect both inputs of a NAND gate to the same signal ; the output is . An AND gate follows by cascading a NAND gate with a NOT gate: the output of the NAND on inputs and feeds into the NOT, yielding . For an OR gate, apply De Morgan's theorem by first inverting the inputs ( and , each via a NAND with tied inputs) and then applying NAND to those inverses: , requiring three NAND gates total. An XOR gate can be built with four NAND gates: let , then , , and output .[9][28][29][30] Similarly, the NOR gate serves as a universal gate through analogous constructions that leverage its disjunctive and inverting properties. A NOT gate is formed by tying both NOR inputs to , yielding . An OR gate is simply a NOR followed by a NOT: . To build an AND gate, invert the inputs first ( and via tied NORs), then apply NOR to those: , using three NOR gates. For XOR, five NOR gates are required, typically by constructing an XNOR with four NOR gates (dual to the NAND XOR) and adding a final NOT.[31][9][25][32] The proof of universality for both NAND and NOR rests on their capacity to generate the primitive operations AND, OR, and NOT, which together form a complete basis for all Boolean functions. Since any Boolean expression can be rewritten in conjunctive or disjunctive normal form using these primitives, and each primitive is constructible from either NAND or NOR alone, any logic circuit can be realized using only that gate type. This functional completeness is verified through the explicit gate constructions outlined above, confirming that no other gate types are needed.[26][33][34] Using universal gates like NAND and NOR offers advantages in circuit design and manufacturing, as they simplify integrated circuit fabrication by reducing the variety of gate types required, leading to more economical production and fewer potential points of failure.[35][36]De Morgan equivalents

De Morgan's laws provide a fundamental duality in Boolean algebra, enabling the transformation of logical expressions involving AND and OR operations through negation. The first law states that the negation of the conjunction of two variables is equivalent to the disjunction of their negations: . The second law states that the negation of the disjunction is equivalent to the conjunction of the negations: .[37] These laws can be verified through exhaustive truth table comparisons, where both sides of each equation yield identical output values for all input combinations of A and B.[38] In digital circuit representation, De Morgan's laws manifest as symbolic equivalents using inversion bubbles on gate inputs and outputs, illustrating the duality between AND and OR gates. For instance, an AND gate with inverted inputs and an inverted output is logically equivalent to an OR gate with non-inverted inputs, as the bubbles represent negations that align with the laws. Similarly, an OR gate with inverted inputs and inverted output equates to an AND gate without inversions. This bubble-pushing technique simplifies schematic diagrams by allowing designers to swap gate types while preserving functionality.[39][40] These equivalents facilitate circuit optimization by enabling redesigns that reduce the number of gates or adapt to specific logic families, such as converting an AND-OR realization to a NAND-NAND structure. Consider a sum-of-products expression implemented as an AND-OR circuit; applying De Morgan's laws to negate and dualize the operations transforms it into a product-of-sums form suitable for NAND gates, often minimizing component count in two-level logic designs.[41][42] The laws extend naturally to multiple variables, maintaining the pattern of duality under negation. For three inputs, and , allowing scalable transformations in complex expressions without altering the overall logic.[43][37]Circuit Applications

Combinational logic

Combinational logic circuits are digital circuits composed of interconnected logic gates where the output values are determined solely by the current input values, without any storage elements or feedback paths that would retain information from previous inputs. This design ensures that the circuit behaves as a pure function of its inputs, producing outputs instantaneously upon input changes. In contrast, sequential logic circuits incorporate memory components, allowing outputs to depend on both current inputs and prior states.[44] A fundamental example of a combinational circuit is the half-adder, which performs binary addition on two single-bit inputs, and , to produce a sum bit and a carry-out bit . The sum is computed using an XOR gate, , while the carry is generated by an AND gate, . This simple structure adds the two bits without considering any incoming carry from a previous stage.[45] The full-adder extends the half-adder to handle three inputs: , , and a carry-in bit , producing sum and carry-out . It can be implemented by cascading two half-adders—the first adding and to generate an intermediate sum and carry, which the second half-adder combines with —followed by an OR gate to compute the final carry: and . Alternatively, it uses two XOR gates, two AND gates, and one OR gate directly for the same functions. Full-adders serve as building blocks for multi-bit adders in arithmetic operations.[45][46] Another key combinational circuit is the multiplexer (MUX), which selects one of several input signals and forwards it to a single output line based on select signals. For a 2-to-1 MUX with inputs , , and select , the output , implemented using AND, OR, and NOT gates. Larger MUXes, such as 4-to-1 with two select bits, use decoders internally to enable one input path via AND-OR logic. Multiplexers are versatile for data routing and implementing arbitrary Boolean functions by connecting variables to selects and constants to inputs.[47][46] The design of combinational circuits typically begins with a truth table specifying outputs for all input combinations, followed by conversion to a canonical form like sum-of-products (SOP), where the output is expressed as an OR of AND terms (minterms) corresponding to rows where the output is 1. For instance, from a truth table, minterms are identified—each a product of all input literals (variables or their complements)—and summed: , where are the minterms. This SOP expression is then realized with AND gates for products, OR gates for summation, and inverters as needed, often minimized using Boolean algebra to reduce gate count.[48][49] Combinational circuits find widespread applications in processors, including arithmetic logic units (ALUs) for operations like addition via chains of full-adders, as well as encoders that convert active inputs to binary codes and decoders that activate one of multiple outputs from a binary address. These components enable efficient data processing and control signal generation without state retention.[44][47]Sequential logic

Sequential logic refers to digital circuits where the output depends not only on the current inputs but also on the previous state of the circuit, achieved through memory elements that incorporate feedback loops and often synchronized by clock signals.[50] These circuits enable state transitions, allowing them to store information and respond to sequences of inputs over time, in contrast to combinational logic which produces instantaneous outputs solely from current inputs.[51] A fundamental building block of sequential logic is the SR latch, constructed using two cross-coupled NOR gates that provide feedback to maintain the output state. The SR latch has two inputs, Set (S) and Reset (R), and two complementary outputs, Q and Q-bar; when S=1 and R=0, Q=1 (set state); when S=0 and R=1, Q=0 (reset state); and when S=0 and R=0, the latch holds its previous state, while S=1 and R=1 is an invalid condition that should be avoided.[52] For clocked operation, an enable input can be added to control when the latch responds to S and R. The D flip-flop extends this by providing edge-triggered storage, typically positive-edge triggered, where the output Q captures the value of the D input precisely at the rising edge of the clock signal and holds it until the next edge. This ensures synchronous behavior in larger systems, preventing race conditions from asynchronous changes. The JK flip-flop addresses limitations of the SR latch by adding toggle functionality; it uses J and K inputs where J=0 and K=0 holds the state, J=1 and K=0 sets Q=1, J=0 and K=1 resets Q=0, and J=1 and K=1 toggles Q to its complement on the clock edge, eliminating the invalid state.[53] Sequential logic finds applications in counters, which increment or decrement a stored value on each clock pulse to track events or generate timing signals; shift registers, which move data bits serially or in parallel for tasks like data buffering and conversion; and finite state machines (FSMs), which model control logic by transitioning between defined states based on inputs and current state.[54][55] Timing in sequential circuits is governed by clock signals that synchronize state changes, with setup time defined as the minimum duration the data input must be stable before the clock edge, and hold time as the minimum duration it must remain stable after the edge, to ensure reliable capture without metastability.[56] These parameters are critical for system reliability, as violations can lead to incorrect state transitions. Flip-flops serve as the core memory elements in static random-access memory (SRAM), where arrays of them store bits addressably, enabling fast read and write operations in computing systems.[57]Implementation

Electronic gates

Electronic logic gates are primarily implemented using semiconductor transistors, with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology serving as the dominant approach due to its low power consumption and high noise immunity.[58] In CMOS, basic gates like AND, OR, and NOT are constructed from pairs of n-channel (NMOS) and p-channel (PMOS) transistors arranged in complementary configurations.[58] The simplest element, the NOT gate or inverter, consists of a single NMOS transistor connected in series with a PMOS transistor between the supply voltage (VDD) and ground, with the input applied to both gates and the output taken from their common drain connection.[58] When the input is high (VDD), the NMOS turns on, pulling the output low (to ground), while the PMOS turns off; conversely, a low input turns the PMOS on, charging the output to VDD, and the NMOS off.[58] More complex gates, such as NAND and NOR, extend this by paralleling PMOS transistors for NAND (or NMOS for NOR) and series-connecting the opposite type, enabling efficient realization of AND and OR functions through De Morgan's theorem.[58] The performance of CMOS gates is influenced by fan-in (number of inputs) and fan-out (number of driven loads), which impact propagation delay due to increased capacitive loading.[58] High fan-in raises internal capacitance, slowing switching, while excessive fan-out—typically limited to over 50 in CMOS before delay becomes prohibitive—requires buffering to maintain speed.[59] Various logic families define the electronic characteristics of these gates, balancing speed, power, and noise margins. Transistor-transistor logic (TTL), using bipolar junction transistors, operates at 5V with a propagation delay of 1.5–33 ns, power dissipation of 1–22 mW per gate, fan-out of 10, and very good noise immunity (DC margins around 0.4V).[60][59] CMOS, leveraging MOSFET pairs, excels in low power (1 mW at 1 MHz, quiescent near 25 nW), excellent noise immunity (margins ~1.5V at 5V), fan-out exceeding 50, but slower propagation (1–200 ns at 3.3–5V).[60][59] Emitter-coupled logic (ECL), also bipolar-based, prioritizes speed with 1–4 ns delays at -5.2V, but at higher power (4–55 mW) and fan-out of 25, with good noise immunity suitable for high-frequency applications.[59] The following table compares key characteristics of these families:| Family | Voltage (V) | Propagation Delay (ns) | Power Dissipation (mW/gate) | Fan-out | Noise Immunity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTL | 5 | 1.5–33 | 1–22 | 10 | Very Good |

| CMOS | 3.3–5 | 1–200 | 1 (at 1 MHz) | >50 | Excellent |

| ECL | -5.2 | 1–4 | 4–55 | 25 | Good |

| Enable (EN) | Input (IN) | Output (OUT) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | Hi-Z |

| 0 | 1 | Hi-Z |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 |