Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

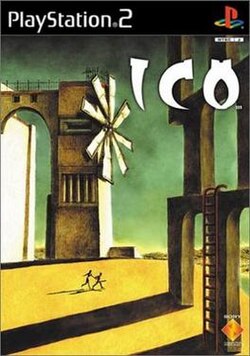

| Ico | |

|---|---|

Cover art of the European and Japanese versions, painted by director Fumito Ueda, and inspired by the Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico's The Nostalgia of the Infinite | |

| Developer | Sony Computer Entertainment Japan |

| Publisher | Sony Computer Entertainment |

| Director | Fumito Ueda |

| Producer | Kenji Kaido |

| Designer | Fumito Ueda |

| Artist | Fumito Ueda |

| Composers |

|

| Platforms | PlayStation 2 PlayStation 3 |

| Release | |

| Genre | Action-adventure |

| Modes | Single-player, multiplayer |

Ico[b] is a 2001 action-adventure game developed and published by Sony Computer Entertainment for the PlayStation 2. It was designed and directed by Fumito Ueda, who wanted to create a minimalist game based on a "boy meets girl" concept. Originally planned for the PlayStation, Ico took approximately four years to develop. The team employed a "subtracting design" approach to reduce elements of gameplay that interfered with the game's setting and story in order to create a high level of immersion.

The player controls Ico, a boy born with horns, which his village considers a bad omen. After warriors lock him in an abandoned castle, he frees Yorda, the daughter of the castle's Queen, who plans to use Yorda to extend her life. Ico must work with Yorda to escape the castle while protecting her from enemies and assisting her across and solving puzzles.

Ico introduced several design and technical elements that have influenced subsequent games, including a story told with minimal dialogue, bloom lighting, and key frame animation. Although not a commercial success, it was acclaimed for its art, original gameplay and story elements and received several awards, including "Game of the Year" nominations and three Game Developers Choice Awards. Considered a cult classic, it has been called one of the greatest video games ever made, and is often brought up in discussions about video games as an art form. It was rereleased in Europe in 2006 in conjunction with Shadow of the Colossus, the spiritual successor to Ico. A high-definition remaster of the game was released alongside Shadow of the Colossus for the PlayStation 3 in The Ico & Shadow of the Colossus Collection in 2011.

Gameplay

[edit]

Ico is primarily a three-dimensional platform game. The player controls Ico from a third-person perspective as he explores the castle and attempts to escape it with Yorda.[3] The camera is fixed in each room or area but swivels to follow Ico or Yorda as they move; the player can also pan the view a small degree in other directions to observe more of the surroundings.[4] The game includes many elements of platform games; for example, the player must have Ico jump, climb, push and pull objects, and perform other tasks such as solving puzzles in order to progress within the castle.[5]

These actions are complicated by the fact that only Ico can carry out these actions; Yorda can jump only short distances and cannot climb over tall barriers. The player must use Ico so that he helps Yorda cross obstacles, such as by lifting her to a higher ledge, or by arranging the environment to allow Yorda to cross a larger gap herself. The player can tell Yorda to follow Ico, or to wait at a particular spot. The player can have Ico take Yorda's hand and pull her along at a faster pace across the environment.[6] Players are unable to progress in the game until they move Yorda to certain doors that only she can open.[3]

Escaping the castle is made difficult by shadow creatures sent by the Queen. These creatures attempt to drag Yorda into black vortexes if Ico leaves her for any length of time, or if she is in certain areas of the castle. Ico can dispel these shadows using a stick or sword and pull Yorda free if she is drawn into a vortex.[3] While the shadow creatures cannot harm Ico, the game is over if Yorda becomes fully engulfed in a vortex; the player restarts from a save point. The player will also restart from a save point if Ico falls from a large height. Save points in the game are represented by stone benches that Ico and Yorda rest on as the player saves the game.[6] In European and Japanese releases, upon completion of the game, the player has the opportunity to restart the game in a local co-operative two-player mode, where the second player plays as Yorda, still under the same limitations as the computer-controlled version of the character. The new game mode also adds in subtitles that translate Yorda's fictional language.[7][8]

Plot

[edit]Ico (イコ), a horned boy, is taken by a group of warriors to an abandoned, desolate castle and locked inside a stone coffin to be sacrificed.[9] A tremor topples the coffin and Ico escapes. As he searches the castle, he comes across Yorda (ヨルダ, Yoruda), a captive girl who speaks a different language. Yorda is magically linked to the castle and has the mystical ability to open various gates, made out of statues resembling Ico, with white energy that emanates from her body. However, she is physically incapable of defending herself. Ico helps Yorda escape and defends her from shadow-like creatures. The pair makes their way through the castle and arrive at the bridge leading to land. As they cross, the Queen, ruler of the castle, appears and tells Yorda that as her daughter she cannot leave the castle.[10] Later, as they try to escape on the bridge, it splits up and they get separated. Yorda tries to save Ico but the Queen prevents it. He ends up falling off the bridge and losing consciousness.

Ico awakens below the castle and makes his way back to the upper levels, finding a magic sword that dispels the shadow creatures. After discovering that Yorda has been turned to stone by the Queen, he confronts the Queen in her throne room, who reveals that she plans to restart her life anew by taking possession of Yorda's body.[11] Ico slays the Queen with the magic sword, but his horns are broken in the fight and at the end of it he is knocked unconscious. With the Queen's death the castle begins to collapse around Ico, but the Queen's spell on Yorda is broken, and a shadowy Yorda carries Ico safely out of the castle to a boat, sending him to drift to the shore alone. Her final phrase "Nonomori" (or "good bye", based on translation give in the subtitle translation of Yorda's language) is spoken by her to Ico as he drifts away from the castle.[8]

Ico awakens on a beach shore to find the distant castle in ruins, and Yorda, in her human form, washed up nearby.[4] She wakes up and smiles at Ico.

Development

[edit]

Lead designer Fumito Ueda came up with the concept for Ico in 1997, envisioning a "boy meets girl" story where the two main characters would hold hands during their adventure, forming a bond between them without communication.[4] Ueda's original inspiration for Ico was a TV commercial he saw, of a woman holding the hand of a child while walking through the woods, and the manga series Galaxy Express 999, where a woman is a guardian for the young hero as they adventure through the galaxy, which he thought about adapting into a new idea for video games.[13] He also cited his work as an animator on Kenji Eno's Sega Saturn game Enemy Zero, which influenced the animation work, cinematic cutscenes, lighting effects, sound design, and mature appeal.[14] Ueda was also inspired by the video game Another World (Outer World in Japan), which used cinematic cutscenes, lacked any head-up display elements as to play like a movie, and also featured an emotional connection between two characters despite the use of minimal dialog.[15][16][17] He also cited Sega Mega Drive games,[18] Virtua Fighter,[19] Lemmings, Flashback and the original Prince of Persia games as influences, specifically regarding animation and gameplay style.[15][17] With the help of an assistant, Ueda created an animation in Lightwave to get a feel for the final game and to better convey his vision.[4] In the three-minute demonstration reel, Yorda had the horns instead of Ico, and flying robotic creatures were seen firing weapons to destroy the castle.[4][20] Ueda stated that having this movie that represented his vision helped to keep the team on track for the long development process, and he reused this technique for the development of Shadow of the Colossus, the team's next effort.[4][21]

Ueda, at the time an employee at Sony Computer Entertainment Japan, began working with producer Kenji Kaido in 1998 to develop the idea and bring the game to the PlayStation. He was granted his own unit as the studio primarily assisted on games from other Japanese developers, with notable exceptions including the Ape Escape series.[22] Ico's design aesthetics were guided by three key notions: to make a game that would be different from others in the genre, feature an aesthetic style that would be consistently artistic, and play out in an imaginary yet realistic setting.[4] This was achieved through the use of "subtracting design"; they removed elements from the game which interfered with the game's reality.[4] This included removing any form of interface elements, keeping the gameplay focused only on the escape from the castle, and reducing the number of types of enemies in the game to a single foe. An interim design of the game shows Ico and Yorda facing horned warriors similar to those who take Ico to the castle. The game originally focused on Ico's attempt to return Yorda to her room in the castle after she was kidnapped by these warriors.[20] Ueda believed this version had too much detail for the graphics engine they had developed, and as part of the "subtracting design", replaced the warriors with the shadow creatures.[4] Ueda also brought in a number of people outside the video game industry to help with development. These consisted of two programmers, four artists, and one designer in addition to Ueda and Kaido.[4][22] On reflection, Ueda noted that the subtracting design may have taken too much out of the game, and did not go to as great an extreme with Shadow of the Colossus.[4]

After two years of development, the team ran into limitations on PlayStation hardware and faced a critical choice: either terminate the project altogether, alter their vision to fit the constraints of the hardware, or continue to explore more options. The team decided to remain true to Ueda's vision, and began to use the Emotion Engine of the PlayStation 2, taking advantage of the improved abilities of the platform.[23][24] Character animation was accomplished through key frame animation instead of the more common motion capture technique.[25] The game took about four years to develop.[4] Ueda purposely left the ending vague, not stating whether Yorda was alive, whether she would travel with Ico, or if it was simply the protagonist's dream.[4]

Ico uses minimal dialogue in a fictional language to provide the story throughout the game.[3] Voice actors included Kazuhiro Shindō as Ico, Rieko Takahashi as Yorda, and Misa Watanabe as the Queen.[26] Ico and the Queen's words are presented in either English or Japanese subtitles depending on the release region, but Yorda's speech is presented in a symbolic language.[3] This symbolic language consists of 26 runic letters which corresponded to the Latin alphabet, and the script was designed by team member Kei Kuwabara.[27] Ueda opted not to provide the translation for Yorda's words as it would have overcome the language barrier between Ico and Yorda, and detracted from the "holding hands" concept of the game.[4] The game initially had 115 lines of spoken dialogue, however 77 of these lines were not used in the final game and can only be accessed via data-mining.[28]

Release

[edit]

The game was released in Japan on December 6, 2001 alongside Yoake no Mariko, developed by another unit of Sony as a collaboration with Spümcø.[30] The North American version was released two months earlier; due to time constraints caused by Sony's planned release date, it lacks the cover art intended by Ueda as well as additional features such as the two-player mode.[31][32] Ueda drew a cover inspired by the Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico and his work The Nostalgia of the Infinite; it was used for the releases in Japan and PAL regions as Ueda was able to complete it for those regions' release dates. Ueda believed that "the surrealistic world of de Chirico matched the allegoric world of Ico".[33] Since release, the North American cover has been considered one of the worst pieces of cover art for video games in contrast to the game's quality.[34][29] On reflection, Yasuhide Kobayashi, vice-president of Sony's Japan division, believed the North American box art and lack of an identifiable English title led to the game's poor sales in the United States, and stated plans to correct that for the release of The Last Guardian.[35] For its original release, a limited edition of the game was available in PAL regions that included a cardboard wrapping displaying artwork from the game and four art cards inside the box.[36] The game was re-released as a standard edition in 2006 across all PAL regions except France after the 2005 release of Shadow of the Colossus, Ico's spiritual sequel, to allow players to "fill the gap in their collection".[37]

Despite the positive reception by critics, the original title did not sell well. By 2009, only 700,000 copies were sold worldwide, with 270,000 in the United States,[35] and the bulk in PAL regions.[22] Ueda considered his design by subtraction approach may have hurt the marketing of the game, as at the time of the game's release, promotion of video games were primarily done through screenshots, and as Ico lacked any heads-up display, it appeared uninteresting to potential buyers.[38]

Other media

[edit]Soundtrack

[edit]Ico's audio featured a limited amount of music and sound effects. The soundtrack, Ico: Kiri no Naka no Senritsu (ICO~霧の中の旋律~, Iko Kiri no Naka no Senritsu; lit. "Ico: Melody in the mist"), was composed by Michiru Oshima and sound unit "pentagon" (Koichi Yamazaki & Mitsukuni Murayama) and released in Japan by Sony Music Entertainment on February 20, 2002. The album was distributed by Sony Music Entertainment Visual Works. The last song of the CD, "ICO -You Were There-", includes vocals sung by former Libera member Steven Geraghty.[39][40]

Novelization

[edit]A novelization of the game titled Ico: Kiri no Shiro (ICO-霧の城-, Iko: Kiri no Shiro; lit. 'Ico: Castle of Mist') was released in Japan in 2004.[41] Author Miyuki Miyabe wrote the novel because of her appreciation of the game.[42] A Korean translation of the novel, entitled 이코 – 안개의 성 (I-ko: An-gae-eui Seong) came out the following year, by Hwangmae Publishers,[43] while an English translation was published by Viz Media on August 16, 2011.[44]

Cross title content

[edit]On June 11th, 2009, costumes (including Ico and Yorda), stickers, and sound effects from Ico were released as part of a paid downloadable add-on pack for the game LittleBigPlanet, titled Team Ico, which was available for download as DLC on the PlayStation Network store alongside similar materials from Shadow of the Colossus, after being teased by the game's developers Media Molecule about two weeks prior.[45][46][47] Ico makes cameo appearances in Astro's Playroom and Astro Bot, Yorda also appearing in the latter.[48][49]

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 90/100[50] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| AllGame | |

| Edge | 8/10[57] |

| Eurogamer | 10/10[51] |

| Famitsu | 30/40[53] |

| GameRevolution | B+[56] |

| GameSpot | 8.5/10[54] |

| IGN | 9.4/10[55] |

| Next Generation |

Ico received critical acclaim, becoming a cult hit among players.[59] The game has an aggregated review score of 90 out of 100 at Metacritic.[50] In Japan, Famitsu magazine gave the PlayStation 2 version a score of 30 out of 40.[53] The game is considered by some to be one of the greatest games of all time; Edge ranked Ico as the 13th top game in a 2007 listing,[60] while IGN ranked the game at number 18 in 2005,[61] and at number 57 in 2007.[62] Ico has been used as an example of a game that is a work of art.[63][64][65] Ueda commented that he purposely tried to distance Ico from conventional video games due to the negative image video games were receiving at that time, in order to draw more people to the title.[66]

Some reviewers have likened Ico to older, simpler adventure games such as Prince of Persia or Tomb Raider, that seek to evoke an emotional experience from the player;[57][63] IGN's David Smith commented that while simple, as an experience the game was "near indescribable."[67] The game's graphics and sound contributed strongly to the positive reactions from critics; Smith continues that "The visuals, sound, and original puzzle design come together to make something that is almost, if not quite, completely unlike anything else on the market, and feels wonderful because of it."[67] Many reviewers were impressed with the expansiveness and the details given to the environments, the animation used for the main characters despite their low polygon count, and the use of lighting effects.[3][5][67] Ico's ambiance, created by the simple music and the small attention to detail in the voice work of the main characters, were also called out as strong points for the game. Charles Herold of The New York Times summed up his review stating that "Ico is not a perfect game, but it is a game of perfect moments."[25] Herold later commented that Ico breaks the mold of games that usually involve companions. In most games these companions are invulnerable and players will generally not concern with the non-playable characters' fate, but Ico creates the sense of "trust and childish fragility" around Yorda, which leads to the character being "the game's entire focus".[68]

The game is noted for its simple combat system that would "disappoint those craving sheer mechanical depth", as stated by GameSpot's Miguel Lopez.[5] The game's puzzle design has been praised for creating a rewarding experience for players who work through challenges on their own;[67] Kristen Reed of Eurogamer, for example, said that "you quietly, logically, willingly proceed, and the illusion is perfect: the game never tells you what to do, even though the game is always telling you what to do".[6] Ico is also considered a short game, taking between seven and ten hours for a single play through, which GameRevolution calls "painfully short" with "no replay outside of self-imposed challenges".[56] G4TV's Matthew Keil, however, felt that "the game is so strong, many will finish 'Ico' in one or two sittings".[3] The lack of features in the North American release, which would become unlocked on subsequent playthroughs after completing the game, was said to reduce the replay value of the title.[3][67] Electronic Gaming Monthly notes that "Yorda would probably be the worst companion -she's scatterbrained and helpless; if not for the fact that the player develops a bond with her, making the game's ending all the more heartrending."[69]

Francesca Reyes reviewed the game for Next Generation, rating it four stars out of five, and stated that "Intensely involving and wonderfully simple, Ico, though flawed, deserves to find its niche as a quiet classic."[58]

Awards

[edit]Ico received several acclamations from the video game press, and was considered to be one of the Games of the Year by many publications, despite competing with releases such as Halo: Combat Evolved, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, and Grand Theft Auto III.[62] The game received three Game Developers Choice Awards in 2002, including "Excellence in Level Design", "Excellence in Visual Arts", and "Game Innovation Spotlight".[70] The game won two Interactive Achievement Awards from the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences in 2002 for outstanding achievement in "Art Direction" and "Character or Story Development"; it also received nominations for "Game of the Year", "Console Game of the Year", "Console Action/Adventure Game of the Year", "Innovation in Console Gaming", and outstanding achievement in "Game Design" and "Sound Design".[71] It won GameSpot's annual "Best Graphics, Artistic" prize among console games.[72] It was one of three titles to win the Special Award at the sixth CESA Game Awards.[73][74]

Legacy

[edit]Ico influenced numerous other video games, which borrowed from its simple and visual design ideals.[38] Several game designers, such as Eiji Aonuma, Hideo Kojima, and Jordan Mechner, have cited Ico as having influenced the visual appearance of their games, including The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, and Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time, respectively.[22] Marc Laidlaw, scriptwriter for the Half-Life series, commented that, among several other more memorable moments in the game, the point where Yorda attempts to save Ico from falling off the damaged bridge was "a significant event not only for that game, but for the art of game design".[75] The Naughty Dog team used Ico as part of the inspiration for developing Uncharted 3.[38] Vander Caballero credits Ico for inspiring the gameplay of Papo & Yo.[76] Phil Fish used the design by subtraction approach in developing the title Fez.[38] The developers of both Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons and Rime have Ico as a core influence on their design.[38] Hidetaka Miyazaki, creator and director of the Dark Souls series, cited Ico as a key influence to him becoming involved in developing video games, stating that Ico "awoke me to the possibilities of the medium".[77] Goichi Suda aka Suda51, said that Ico's save game method, where the player has Ico and Yorda sit on a bench to save the game, inspired the save game method in No More Heroes where the player-character sits on a toilet to save the game.[78]

Ico was one of the first video games to use a bloom lighting effect, which later became a popular effect in video games.[1] Patrice Désilets, creator of Ubisoft games such as Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time and Assassin's Creed, cited Ico as an influence on the game design of The Sands of Time.[79][80] Jenova Chen, creator of art games such as Flower and Journey, cited Ico as one of his biggest influences.[81] Ico was also cited as an influence by Halo 4 creative director Josh Holmes.[38] Naughty Dog said The Last of Us was influenced by Ico, particularly in terms of character building and interaction,[82] and Neil Druckmann credited the gameplay of Ico as a key inspiration when he began developing the story of The Last of Us.[83][84]

Film director Guillermo del Toro cited both Ico and Shadow of the Colossus as "masterpieces" and part of his directorial influence.[85] Jonny Greenwood of Radiohead considers it one of his top ten video games of all time, saying it "might be the best one".[86][87]

Other Team Ico games

[edit]Shadow of the Colossus was developed by the same team and released for the PlayStation 2 in 2005. The game features similar graphics, gameplay, and storytelling elements as Ico. The game was referred by its working title "Nico" ("Ni" being Japanese for the number 2") until the final title was revealed.[88] Ueda, when asked about the connection between the two games, stated that Shadow of the Colossus is a prequel to Ico.[66]

The team's third game, The Last Guardian, was announced for the PlayStation 3 at E3 2009. The game centers on the connection between a young boy and a large griffin-like creature that he befriends, requiring the player to cooperate with the creature to solve the game's puzzles. The game fell into development hell due to hardware limitations and the departure of Ueda from Sony around 2012, along with other Team Ico members, though Ueda and the other members continued to work on the game via consulting contracts. Development subsequently switched to the PlayStation 4 in 2012, and the game was reannounced in 2015 and released in December 2016.[89][90] Ueda has said that "the essence of the game is rather close to Ico".[91]

HD remaster

[edit]Ico, along with Shadow of the Colossus, received a high-definition remaster for the PlayStation 3 that was released worldwide in September 2011. In addition to improved graphics, the games were updated to include support for stereoscopic 3D and PlayStation Trophies. The Ico port was also based on the European version, and includes features such as Yorda's translation and the two-player mode.[92] In North America and Europe/PAL regions, the two games were released as a single retail collection,[93] while in Japan, they were released as separate titles.[94] Both games have since been released separately as downloadable titles on the PlayStation Network store.[95] Patch 1.01 for the digital high-definition Ico version added the Remote Play feature, allowing the game to be played on the PlayStation Vita.[96]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Mielke, James (October 15, 2005). "Bittersweet Symphony". 1UP. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ Banks, Dave (September 8, 2011). "Two Classic Games Get Facelifts and a PlayStation 3 Release". Wired. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Keil, Matthew (September 30, 2002). "'Ico' (PS2) Review". G4TV. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "The Method of Developing ICO". 1UP. October 10, 2000. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Lopez, Miguel (September 26, 2001). "Ico for PlayStation 2 Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Reed, Kristen (February 17, 2006). "Ico Review". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ Davidson, Drew (2003). Interactivity in Ico: Initial Involvement, Immersion, Investment. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Vol. 38 – Proceedings of the second international conference on Entertainment computing. Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Mecheri, Damien (2019). "Chapter 1 - Creation". The Works of Fumito Ueda: A Different Perspective on Video Games. Third Creations. ISBN 2377842321.

- ^ Sony Computer Entertainment (September 24, 2001). Ico (PlayStation 2). Sony Computer Entertainment.

Ico: They ... They tried to sacrifice me because I have horns. Kids with horns are brought here.

- ^ Sony Computer Entertainment (September 24, 2001). Ico (PlayStation 2). Sony Computer Entertainment.

Queen: That girl you're with is my one and only beloved daughter. Stop wasting your time with her. She lives in a different world than some boy with horns! [...] Yorda, why can't you understand? You cannot survive in the outside world.

- ^ Sony Computer Entertainment (September 24, 2001). Ico (PlayStation 2). Sony Computer Entertainment.

Queen: My body has become too old and won't last much longer. But Yorda's going to grant me the power to be resurrected. To be my spiritual vessel is the fulfilment of her destiny.

- ^ Wen, Alan (September 21, 2021). "20 years later, 'Ico' remains a minimalist masterclass in cinematic and emotional storytelling". NME. Archived from the original on March 31, 2025. Retrieved April 15, 2025.

- ^ "The PlayStation 2 Interview: Fumita Ueda", Official PlayStation 2 Magazine, no. 19, April 2002

- ^ "'The Last Guardian' Creator Ueda on His First Game Job and the Late Kenji Eno". Glixel. January 6, 2017. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ a b "5 days straight! Hiroshi famous game creators say that! The third, Fumito Ueda" (in Japanese). Famitsu. April 3, 2007. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ Elliott, Phil (January 16, 2007). "Q&A: Another World's Eric Chahi". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 18, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Fitsko, Matthew (April 11, 2007). "Japanese devs speak out on behalf of Western Gaming – Part 2". GamePro. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ^ blackoak. "ICO – 2002 Developer Interview". Shmuplations. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ Watch The Last Guardian’s spectacular new CG trailer Archived August 25, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, PlayStation Blog, PlayStation Network

- ^ a b "Unreleased ICO PS1 'Beta' gameplay". 1UP. March 14, 2007. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ Cifaldi, Frank (February 14, 2006). "DICE: Climbing The Colossus: Ueda, Kaido On Creating Cult Classics". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c d DeRienzo, David. "Hardcore Gaming 101: ICO / Shadow of the Colossus". Hardcore Gaming 101. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ Ueda, Fumito; Kaido, Kenji (March 24, 2004). Game Design Methods of Ico. Game Developers Conference 2004.

- ^ Yasushi, Hitoshi (March 29, 2004). "Game Developers Conference 2004 – report" (in Japanese). Game Watch. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ a b Herold, Charles (October 18, 2001). "Game Theory; When a Tiny Taut Gesture Upstages Demons and Noise". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "ICO Tech Info". GameSpot. Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ James Riley, Samuel (April 13, 2015). "Gaming's weird, mysterious, fictional languages, explained and translated". GamesRadar+. Retrieved June 23, 2025.

- ^ Matulef, Jeffrey (July 21, 2015). "Ico's original script has been translated". Eurogamer.net. Archived from the original on December 1, 2024. Retrieved June 23, 2025.

- ^ a b McWhertor, Michael (October 26, 2016). "Shadow of the Colossus and Ico's non-terrible box art now prints for your home". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ "Jスタクリエイターがファンのみなさんをおもてなし! 「JAPAN Studio "Fun" Meeting 2018」レポート". PlayStation.Blog (in Japanese). December 3, 2018. Archived from the original on July 13, 2024. Retrieved January 1, 2025.

- ^ "ICO Hints & Cheats". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 15, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- ^ Mielke, James (October 13, 2005). "Shadow Talk". 1UP. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2008.

- ^ Mielke, James; Rybicki, Joe (September 23, 2005). "A Giant in the Making". 1UP. Archived from the original on March 6, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ Taljonik, Ryan (August 21, 2013). "12 great games with god-awful box art". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Elliot, Phil (September 17, 2009). "Last Guardian game 'named for US, Europe' Kobayashi". GamesIndustry.biz. Archived from the original on December 17, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2009.

- ^ Wales, Matt (2006). "PAL Colossus gets exclusive content". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Reed, Kristen (November 4, 2005). "ICO re-issue confirmed". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Kohler, Chris (September 12, 2013). "The Obscure Cult Game That's Secretly Inspiring Everything". Wired. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ "Steven Geraghty". Boy Choir and Soloist Directory. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- ^ "Melody light comfort that invites the ultimate healing of hard Romantic. ... Released Soon!" (in Japanese). HMV. June 1, 2003. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

大島ミチルが手掛けたゲーム・サントラICO霧の中の旋律ではLiberaリベラのヴォーカリストSteven Geraghtyスティーブン・ガラティがヴォーカルで参加" – "Oshima Michiru who managed the game soundtrack for ICO with vocals by Steven Geraghty of Libera

- ^ Miyabe, Miyuki (2011). ICO: Castle in the Mist [Iko: Kiri no Shiro] (Haikasoru eBook ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4215-4286-7.

- ^ "ICO Novel Coming In Japan". IGN. May 1, 2002. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "ICO: Castle of Mist" (in Korean). Hwangmae Publishers. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- ^ Caoili, Eric (January 31, 2011). "Viz Media Publishing Miyuki Miyabe's Ico Novel". GameSetWatch. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Media Molecule - we make games. » Blog Archive » Store update: Team ICO Pack". www.mediamolecule.com. Archived from the original on June 16, 2009. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ Ig, Keane (May 29, 2009). "ICO Invading LittleBigPlanet?". The Escapist. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- ^ Boyer, Brandon (June 8, 2009). "LittleBigWatch: Media Molecule reveal Ico, Yorda costumes". Offworld. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- ^ "Every cameraman reference in Astro's Playroom". Gamepur. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Bowen, Tom (September 5, 2024). "All Cameo Bots in Astro Bot". Game Rant. Archived from the original on March 13, 2025. Retrieved March 24, 2025.

- ^ a b "Ico (ps2: 2001)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 11, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ^ Bramwell, Tom (March 30, 2002). "Ico". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Frankle, Gavin. "Ico – Review". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "プレイステーション2 – ICO (PlayStation 2 – Ico)". Famitsu (in Japanese). Vol. 915, no. 2. June 30, 2006. p. 90.

- ^ Lopez, Miguel (September 26, 2001). "Ico Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Smith, David (September 25, 2001). "Ico". IGN. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ a b Liu, Johnny (October 9, 2001). "'Ico' (PS2) Review". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- ^ a b "Ico". Edge. No. 104. Future Publishing. December 2001. pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b Reyes, Francesca (November 2001). "Finals". Next Generation. Vol. 4, no. 11. Imagine Media. p. 105.

- ^ "Top 10 Cult Classics". 1UP. June 22, 2005. Archived from the original on May 25, 2016. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "Edge's Top 100 Games of All Time". Edge. July 2, 2007. Archived from the original on August 3, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ "IGN's Top 100 Games". IGN. 2005. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ a b "The Top 100 Games of All Time!". IGN. 2007. Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ a b Hoggins, Tom (July 26, 2008). "Why videogamers are artists at heart". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Herold, Charles (November 15, 2001). "Game Theory; To Play Emperor or God, or Grunt in a Tennis Skirt". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Alupului, Andrei (October 2001). "Reviews: ICO". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 21, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ a b Wired. "Behind the Shadow: Fumito Ueda". WIRED. Archived from the original on July 20, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, David (September 25, 2001). "Ico". IGN. Archived from the original on August 17, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ Herold, Charles (2009). "Ico: Creating an Emotional Connection with a Pixelated Damsel". In Drew Davidson; et al. (eds.). Well Played 1.0: Video Game, Value and Meaning. ETC Press. ISBN 978-0557069750. Archived from the original on March 21, 2016.

- ^ Jeremy Parish, "Best Buddies & Foul-weather Friends: A history of co-op games, good and bad", Electronic Gaming Monthly 234 (November 2008): 92.

- ^ "Game Developers Choice Awards Recipients Named". International Game Developers Association. March 22, 2002. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ "5th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards". Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. February 25, 2002. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2011.

- ^ GameSpot VG Staff (February 23, 2002). "GameSpot's Best and Worst Video Games of 2001". GameSpot. Archived from the original on August 3, 2002.

- ^ "GAME AWARDS 2001-2002: 特別賞". 発表授賞式. 第6回 CESA GAME AWARDS. Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "ICO". GAME AWARDS 2001-2002 特別賞受賞作品. 第6回 CESA GAME AWARDS. Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association.

- ^ Carless, Simon (October 8, 2008). "Marc Laidlaw On Story And Narrative In Half-Life". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (August 27, 2012). "Review: Autobiographical Story of Child Abuse Papo & Yo Pushes Games Forward, Awkwardly". Wired. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ^ Parkin, Simon (March 31, 2015). "Bloodborne creator Hidetaka Miyazaki: 'I didn't have a dream. I wasn't ambitious'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Scullion, Chris (December 6, 2021). "Top game designers pay tribute to Ico on its 20th anniversary in Japan". Video Games Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- ^ "'Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time' director looks back on the iconic game in 'Devs Play' video". SiliconANGLE. December 23, 2015. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ "Devs Play S2E03 · "Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time" with Patrice Désilets and Greg Rice". YouTube. Double Fine Productions. December 22, 2015. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Glen (September 18, 2006). "Joystiq interview: Jenova Chen". Joystiq. Archived from the original on January 2, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2011.

- ^ Prestia, Gaetano. "The Last Of Us inspired by Ico, RE4 – PS3 News | MMGN Australia". Ps3.mmgn.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (September 19, 2013). "The power of failure: making 'The Last of Us'". The Verge. Vox Media. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Barasch, Alex (December 26, 2022). "Can "The Last of Us" Break the Curse of Bad Video-Game Adaptations?". New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Hellboy Director Talks Gaming". Edge. August 26, 2008. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ^ Greenwood, Jonny (June 3, 2010). "Jonny Greenwood list". Archived from the original on December 1, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ "Radiohead's Jonny Greenwood lists his current top 10 video games". The Independent. June 3, 2010. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Ed (July 10, 2004). "NICO Semi-Confirmed". IGN. Archived from the original on August 26, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ^ Roper, Chris (January 24, 2008). "Team ICO's Next". IGN. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ "Yoshida: Team ICO's PS3 game will be shown "soon"". Video Gaming 24/7. July 28, 2008. Archived from the original on December 18, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ^ Breckon, Nick (May 19, 2009). "Early Trailer for Team Ico's 'Project Trico' Leaked?". Shacknews. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2009.

- ^ Nutt, Christian (September 16, 2010). "TGS: Reawakening The Last Guardian". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ Shuman, Sid (September 16, 2010). "Ico and Shadow of the Colossus Collection hits PS3 Spring 2011 with 3D". Sony Computer Entertainment of America. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ Gantayat, Anoop (September 14, 2010). "Ico and Shadow of the Colossus Remakes Confirmed". IGN. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ Moriarty, Colin (January 12, 2012). "Shadow of the Colossus and ICO Coming to PSN". IGN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ Hussain, Tamoir (September 4, 2012). "Ico HD playable on Vita with Remote Play update". Computer and Video Games. Archived from the original on December 2, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Christensen, Ida Broni (May 2022). "'Right-hand Pixels': Controlling Companions and Employing Haptic Storytelling Techniques in Single-player Quest-based Videogames". Play Don’t Show—Video Game Companions. Narrative. 30 (2): 183–191. doi:10.1353/nar.2022.0033.

- McDonald, Peter Douglas (Spring 2012). "Playing Attention: The Hermeneutic Problems of Reading Ico Closely". Loading: The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association. 6 (9): 36–52.

External links

[edit]- Ico at MobyGames

- Early development video assembled by GenDesign

Gameplay and Design

Core Mechanics

Ico's core mechanics revolve around third-person exploration and interaction in a 3D environment, controlled via the PlayStation 2's DualShock 2 controller. The left analog stick handles Ico's movement, allowing running, walking, and navigation across castle terrains, while the right analog stick pans the semi-fixed camera to view surroundings.[7] Basic interactions include jumping with the Triangle button to reach higher platforms, grab and climb ledges, or swing on chains and ropes.[7] The Circle button performs contextual actions like pushing objects, while the X button is used to drop from ledges, enabling environmental manipulation essential for progression.[7][8] A central mechanic is guiding Yorda, the non-player character companion, by holding her hand with the R1 button, which slows Ico's pace to match her limited mobility and fosters a protective dynamic.[9][8] This hand-holding allows players to pull Yorda up to platforms or lead her through areas, with subtle haptic feedback via the controller's rumble enhancing the sense of connection.[10] If Yorda is separated from Ico for too long—by releasing R1 or environmental obstacles—shadow creatures may capture her, resulting in an immediate game over, emphasizing the risk of detachment.[9] Players can call Yorda to their location using R1 if she lags behind, integrating her AI into core navigation without direct control.[7] Combat involves defending against shadow creatures using improvised weapons like wooden sticks or metal swords found scattered in the environment, activated by pressing Square to perform strikes.[9] These ethereal enemies emerge from portals and pursue primarily Yorda, but attacks on Ico trigger a knockdown animation rather than lethal damage, as the game features no traditional health bar.[11] Players can exploit environmental hazards, such as explosive barrels or ledges, to dispatch groups of shadows more efficiently, prioritizing protection over aggressive engagement.[9] Being repeatedly knocked down extends recovery time through prolonged animations, heightening vulnerability during encounters.[12] Progression and limited recovery rely on satyr statues, glowing stone idols placed at key points throughout the castle, which Yorda activates by touch to dispel barriers and advance the path forward.[2] These statues also provide restoration for Ico; if knocked down nearby, interacting with an activated idol revives him immediately, serving as the game's sole healing mechanism amid otherwise unforgiving knockdown states.[11][13] This ties basic interactions directly to advancement, with puzzles briefly referencing these mechanics to unlock new areas without complex inventory or resource management.[2]Puzzles and Exploration

The castle in Ico features levels structured as interconnected areas, forming a labyrinthine ruin that necessitates backtracking to access new paths and advance through the environment. This design fosters a sense of continuity and immersion, with players revisiting earlier sections to apply newly acquired abilities or insights, as emphasized by director Fumito Ueda's approach to building the world directly in 3D for organic connectivity.[2] Light-based progression is a core navigation element, where environmental fog and vast ocean views restrict distant visibility to maintain focus on immediate surroundings and build atmospheric tension, while the player's sword serves to illuminate and activate key mechanisms for forward movement.[2] Puzzles primarily revolve around environmental interactions, such as pulling levers to trigger doors or platforms, constructing or lowering bridges to span chasms, and manipulating water flows to redirect streams or fill reservoirs, all manually animated to enhance realism within the PlayStation 2's technical constraints.[2] These challenges integrate seamlessly with the surroundings, requiring observation and experimentation rather than complex inventories. Yorda contributes uniquely to puzzle resolution by activating elevated or distant mechanisms inaccessible to Ico, such as magical portals or switches, compelling players to escort her strategically across obstacles. The hand-holding mechanic aids this cooperative dynamic, enabling guided movement through precarious areas as part of both progression and interaction.[2] Exploration yields rewards like concealed rooms containing collectible ethereal swords or scenic vistas, encouraging non-linear detours and repeated visits to areas within the overarching linear path, which supports Ueda's philosophy of empowering player-driven discovery in a minimalist framework.[2]Story and Setting

Plot Summary

Ico, a young boy born with horns that mark him as cursed in his isolated village, is ritually sacrificed by being transported to a remote, ancient castle and sealed inside a stone sarcophagus. The ritual is intended to appease malevolent spirits, but Ico awakens prematurely and breaks free, beginning his exploration of the fortress's vast, labyrinthine interior filled with crumbling stone walls, overgrown courtyards, and forgotten mechanical devices.[14] Wandering the dimly lit halls, Ico discovers a mysterious, ethereal girl named Yorda imprisoned within a translucent cage suspended above a pool of water. He frees her by manipulating the environment to lower the cage, and the two embark on a perilous journey through the multi-tiered castle to reach an exit leading to the mainland. Unable to speak the same language, Ico holds Yorda's hand to guide her across precarious platforms and through hazardous areas; she, in turn, activates glowing mechanisms that unlock sealed doors and bridges, revealing paths forward. Throughout their trek, they are repeatedly assaulted by dark, amorphous shadow creatures that emerge from the ground to seize Yorda and drag her back toward the castle's depths.[14] The duo navigates increasingly treacherous sections of the fortress, including wind-swept towers, underground aqueducts, and a massive garden overrun by spectral foes, gradually unveiling the castle's mythical origins as a prison built to contain otherworldly powers. Their progress is hindered by the castle's ruler, the Queen, who reveals herself as Yorda's mother and the architect of the imprisonment, seeking to harvest her daughter's vital essence to achieve eternal youth.[15] The narrative builds to a climax at the castle's grand entrance, where Ico confronts the Queen in her throne room. Arming himself with the sword he found earlier in the castle, Ico defeats her, but the mortally wounded Queen retaliates by causing the long stone bridge connecting the island castle to the distant shore to shatter.[16] Yorda is ensnared by intensified shadow attacks and pulled away, while Ico, gravely injured, plummets from the collapsing structure into the churning sea below.[14] In the game's ambiguous conclusion, Ico washes ashore on a sandy beach far from the castle, weakened but alive. Hearing a distant sound, he approaches a large coffin that has drifted in from the wreckage. Opening it, he finds Yorda inside, her health restored and her form stabilized. The pair clasps hands and walks together toward the horizon as the sun sets, leaving Ico's long-term fate and the full implications of their escape unresolved.[14]Characters and Themes

Ico, the titular protagonist, is depicted as a young boy born with horns, a physical trait that brands him an outcast destined for sacrificial imprisonment in his village's ancient rite, symbolizing profound isolation and the quiet heroism of defying societal rejection.[17] This design choice underscores his vulnerability and determination, positioning him as a relatable figure whose actions drive the narrative toward redemption and connection.[18] Yorda, the ethereal princess Ico encounters, embodies vulnerability through her silent demeanor and fragile movements, requiring constant guidance and protection, which evokes themes of interdependence and emotional fragility.[19] Her otherworldly appearance and inability to speak reinforce her as a symbol of innocence trapped in peril, fostering a player-driven bond that highlights mutual reliance without explicit instruction.[17] In contrast, the Queen serves as the central antagonist, her ghostly, imposing form representing entrapment and overbearing maternal control, as she seeks to bind Yorda eternally within the castle to preserve her own immortality.[18] The game's core themes revolve around companionship, illustrated by the hand-holding mechanic that physically and emotionally links Ico and Yorda, promoting a selfless partnership amid adversity.[17] Sacrifice permeates the experience, as characters confront personal loss for greater liberation, while the tension between freedom and captivity manifests in the labyrinthine castle, a prison of shadows and secrets.[20] This minimalistic storytelling relies on actions and subtle environmental interactions rather than dialogue, amplifying emotional resonance through implication.[19] Subtle motifs, such as the interplay of light and darkness—evoking hope against despair—and wordless communication, deepen the philosophical exploration of human bonds and escape from isolation.[21]Development

Concept and Influences

Fumito Ueda's vision for Ico centered on a "boy meets girl" adventure, featuring a young boy guiding and protecting a fragile girl as they attempt to escape an ancient, foreboding castle. This core premise stemmed from a short pilot animation Ueda produced in 1997 using Lightwave 3D software, in which a boy in a red shirt rescues a princess from a tower, and the pair flees together by boat at the end.[22] The animation served as the foundational blueprint for the game's narrative and mechanics, with Ueda aiming to evoke emotional connection through subtle interactions rather than explicit exposition.[2] Ueda drew initial inspiration for the hand-holding dynamic from a Japanese TV commercial depicting a woman leading a child by the hand through a wooded path, symbolizing trust and companionship.[9] He sought to craft a minimalist experience with no spoken dialogue, relying instead on environmental storytelling, body language, and player actions to convey themes of isolation, sacrifice, and budding alliance between the protagonists.[23] This approach was influenced by earlier adventure games like Another World (1991), which emphasized atmospheric visuals and puzzle-solving over verbose narratives. Early prototypes emphasized cooperative elements, such as the boy physically supporting the girl to navigate obstacles, fostering a sense of mutual dependence. Shadow-like enemies were introduced as ethereal pursuers, representing intangible threats that heightened the game's tension without relying on traditional combat. These design choices prioritized emotional immersion, setting Ico apart from contemporary action-adventure titles by focusing on quiet exploration and relational bonds.[2]Production and Challenges

Development of Ico was handled by Team Ico, a specialized unit within Sony Computer Entertainment's Japan Studio, spanning from 1998 to 2001, with Fumito Ueda serving as director, designer, and art director. The project began as a prototype for the PlayStation 1 before being ported to the PlayStation 2 due to expanding technical needs.[2] The small team of approximately 20 members focused on creating a minimalist experience, iterating on Ueda's initial "boy meets girl" concept to emphasize emotional connection over complex mechanics.[2] Technical innovations were central to the production, particularly in rendering the game's haunting castle environment. The team developed a dynamic lighting system that supported real-time shadows and volumetric fog, enhancing the sense of isolation and mystery without relying on pre-baked effects.[2] These features required extensive optimization to run smoothly on the hardware, often involving manual adjustments to polygon counts and texture resolutions. The project encountered significant challenges stemming from a constrained budget, which limited resources and necessitated asset reuse across levels to construct the expansive yet sparse castle interiors.[2] A primary technical hurdle was Yorda's AI, as the developers grappled with programming her to follow Ico autonomously while appearing vulnerable and in need of protection; early versions made her too independent or prone to glitches, leading to repeated overhauls for more nuanced pathfinding and interaction behaviors.[2] Multiple levels were ultimately scrapped, including more action-oriented sections that clashed with the game's subdued pace, to preserve thematic consistency and avoid scope creep.[2] Sound design and voice acting choices further reflected the team's commitment to subtlety. Ueda insisted on silent protagonists for both Ico and Yorda to foster player immersion and universality, eschewing traditional dialogue to let actions and environmental audio convey the narrative.[22] Yorda's limited vocalizations were recorded in an invented language without subtitles, performed by Japanese actress Rieko Takahashi to evoke an otherworldly quality, while the overall audio emphasized ambient echoes, distant echoes, and Michiru Oshima's ethereal score to heighten emotional tension.[2][24] These decisions, though challenging to integrate without overpowering the visuals, reinforced the game's focus on quiet companionship.[22]Release and Distribution

Launch Platforms and Dates

Ico was developed and published exclusively for the PlayStation 2 by Sony Computer Entertainment as part of its initial launch strategy for the console's mature library. The game debuted in North America on September 24, 2001, marking it as one of the platform's key artistic offerings amid a lineup dominated by high-action titles like Gran Turismo 3 and Metal Gear Solid 2. This staggered rollout prioritized Western markets before circling back to Japan, reflecting Sony's aim to build international momentum for the title's innovative design.[4][25] Following the North American premiere, Ico launched in Japan on December 6, 2001, and in Europe on March 22, 2002. The Japanese version, released under the catalog number SCPS-11003, carried a standard retail price of ¥3,800 (approximately $32 USD at the time), while the North American edition (SCUS-97113) retailed for $49.99 USD, aligning with premium PS2 pricing for new releases. European copies (SCES-50760) were similarly priced at around €49.99, with a limited edition variant including collectible art cards and a reversible cover featuring concept artwork by director Fumito Ueda. The North American release used a black label CD-ROM format, whereas European versions shipped on DVD-ROM for enhanced compatibility with regional hardware standards. These packaging choices emphasized the game's ethereal aesthetic, with Ueda's minimalist illustrations adorning covers to evoke mystery and isolation.[1][26][27] Sony's marketing campaign positioned Ico as a departure from the PS2's action-heavy blockbusters, highlighting its sparse narrative, hand-holding mechanic, and atmospheric exploration to appeal to players seeking emotional depth over spectacle. Trailers and print ads, such as those in Official U.S. PlayStation Magazine (Issue 51, August 2001), showcased surreal castle vistas and the bond between protagonists Ico and Yorda, using taglines like "A boy's only companion is his courage" to underscore its artistic ambitions. However, the minimalist approach proved challenging for promotion; Sony's marketing team reportedly struggled to convey the game's subtle storytelling without relying on explosive visuals, leading to subdued advertising that contrasted sharply with campaigns for titles like Grand Theft Auto III. A notable misstep was the North American box art, which deviated from Ueda's intended ethereal design in favor of a more generic fantasy illustration, diluting the title's unique identity.[20][28] Localization efforts focused on adapting the game's fictional, non-verbal language—consisting of gibberish vocalizations rather than scripted dialogue—for global accessibility, requiring no direct translation of spoken content. English subtitles were minimal and environmental, appearing only for key interactions like door-opening prompts, and were implemented uniformly across regions to preserve the enigmatic tone. The audio tracks remained unchanged worldwide, with the same ethereal sound design by Michiru Oshima, ensuring Yorda's calls and shadow creature growls retained their universal ambiguity. Regional variations arose primarily from development timelines rather than cultural adjustments; the rushed North American version omitted several second-playthrough bonuses and featured simplified puzzle animations (e.g., shadow creatures with reduced attack variety) present in the fuller Japanese and European editions. No explicit censorship was applied, though minor graphical tweaks, such as adjusted shadow behaviors, were made to align with PAL video standards in Europe. These differences stemmed from ongoing refinements during the staggered rollout, briefly referencing production delays that forced an earlier U.S. ship date.[29][30]Commercial Performance

_Ico achieved modest commercial success following its initial release, selling approximately 470,000 units worldwide.[31] Of these, sales were stronger in Japan, where the game performed better relative to other regions, contributing around 230,000 units compared to about 180,000 in North America and 60,000 in Europe.[31][32] This regional disparity was influenced by the game's launch in North America on September 24, 2001, prior to Japan on December 6, 2001.[25] The game's niche appeal, characterized by its minimalist storytelling and puzzle-focused gameplay, limited its mainstream traction amid a crowded PlayStation 2 market dominated by high-action titles. For instance, contemporaries like Grand Theft Auto III, released shortly after Ico in October 2001, sold over 14.5 million units globally, underscoring the challenges faced by more artistic, less conventional exclusives.[25] In the United States, suboptimal marketing—particularly the poorly received box art featuring a generic warrior figure—further hampered visibility and initial sales.[25] The PS2's market saturation by 2001, with approximately 20 million units shipped worldwide by late in the year, intensified competition from blockbuster Sony exclusives and third-party hits, diluting attention for experimental titles like Ico.[33] Re-releases helped extend the game's commercial lifespan and boost cumulative sales. In Europe, a Platinum edition—Sony's equivalent to the Greatest Hits program—was issued in February 2006, capitalizing on renewed interest following the release of Shadow of the Colossus in 2005.[34] This budget re-release made the title more accessible in PAL regions, where initial shipments had been limited, contributing to incremental growth in overall figures.[34]Adaptations and Expansions

Soundtrack

The soundtrack of Ico was composed primarily by Michiru Oshima, with arrangements and additional contributions from the musical group Pentagon, blending orchestral elements with minimalist ambient compositions to evoke the game's themes of isolation and quiet wonder. Oshima, known for her work on anime and video game scores, crafted tracks that emphasize sparse, atmospheric soundscapes using a limited palette of instruments, including harp for delicate, echoing melodies, sweeping strings for emotional depth, and subtle percussion to underscore moments of subtle tension.[35] This approach mirrors the game's design philosophy, prioritizing restraint to heighten the player's sense of solitude in the vast, misty castle environments.[36] Prominent tracks include "Prologue," which introduces the haunting, ethereal tone with soft harp and string motifs, setting a contemplative mood from the outset, and "Escape," where building layers of strings and light percussion convey urgency and resolve as the protagonists flee peril.[37] Other notable pieces, such as "Castle in the Mist" and "You Were There," feature vocal elements performed by Steven Geraghty, adding a layer of lyrical intimacy that ties into the narrative's focus on companionship amid desolation.[38] The overall style relies on repetitive chord progressions—often built around just three chords—to create a hypnotic, immersive quality, avoiding bombast in favor of subtlety that amplifies the game's emotional resonance.[35] Released commercially as ICONovelization and Merchandise

In 2004, Japanese author Miyuki Miyabe penned a novelization of Ico titled ICO: Castle in the Mist, which was serialized in the magazine Shūkan Gendai from May 2002 to May 2003 before appearing in book form on June 16, 2004.[41][42] The work transforms the game's minimalist narrative into a fuller fantasy tale, providing detailed backstories for the characters, including Ico's upbringing in a superstitious village that brands horned boys as omens of misfortune and Yorda's origins as a princess entangled in ancient royal curses.[43] Miyabe's adaptation emphasizes themes of sacrifice and redemption, diverging from the game's ambiguity to explore the mythological forces behind the Castle in the Mist while preserving its core emotional bond between Ico and Yorda.[44] An English translation by Alexander O. Smith was published by VIZ Media on August 16, 2011, introducing the expanded lore to international audiences.[45] Official merchandise for Ico was primarily released in Japan by Sony Computer Entertainment, focusing on collectible items tied to the game's 2001 launch and later re-releases. The ICO Official Guide Book, published in 2002, serves as a key visual companion, featuring concept sketches of the castle architecture, character designs, and interviews with director Fumito Ueda discussing the game's artistic inspirations.[46] Limited apparel, such as PlayStation-branded t-shirts depicting Ico and Yorda holding hands, was distributed through Sony's promotional channels in Japan during the PS2 era and the 2011 HD collection with Shadow of the Colossus.[47] While official figurines were scarce, Unofficial fan merchandise has sustained Ico's cult following, with creators producing apparel, posters, and prints inspired by the game's ethereal aesthetic on platforms like Redbubble and Etsy.[48] These items, often featuring minimalist interpretations of the castle or the duo's journey, reflect the title's enduring cultural footprint in gaming communities, where fans recreate Ueda's vision through custom art and accessories that evoke the game's themes of isolation and companionship.[49]Cross-Media Content

Ico appeared in Sony's official compilation The Ico & Shadow of the Colossus Collection, released for PlayStation 3 on September 27, 2011, which remastered both titles in 1080p high definition, added stereoscopic 3D support, enhanced audio up to 7.1 surround sound, and introduced PlayStation Network trophy integration to make the interconnected experiences more accessible to new audiences.[50] Fan communities have produced various works extending Ico's universe, including texture replacement remasters that enhance visuals with modern post-processing and custom content like alternative costumes for protagonists Ico and Yorda, though these remain unofficial projects shared among enthusiasts.Reception and Analysis

Critical Reviews

Upon its release, Ico received widespread critical acclaim, earning an aggregate score of 90 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 59 reviews.[4] Critics frequently lauded the game's atmospheric design and innovative approach to puzzle-platforming, which emphasized exploration and subtle environmental storytelling over traditional action elements. The title's emotional depth, conveyed through minimal dialogue and the player's protective relationship with Yorda, was highlighted as a standout feature, creating a poignant sense of companionship and vulnerability.[51] Level design was another common point of praise, with reviewers appreciating the castle's interconnected architecture that encouraged organic discovery and replayability without overt guidance.[52] Despite the overwhelmingly positive reception, some critics noted drawbacks, particularly the game's brevity—typically lasting 4 to 6 hours—and occasional frustrations with Yorda's AI, which could lead to repetitive escort mechanics and moments of player irritation during navigation.[53] These elements were seen as minor trade-offs for the overall artistic vision, though they occasionally disrupted the immersive flow. Electronic Gaming Monthly awarded Ico an 8.7 out of 10, naming it Game of the Month and commending director Fumito Ueda's distinctive style of "design by subtraction," which stripped away excess to focus on core emotional and exploratory experiences.[54] Similarly, IGN gave the game a 9.4 out of 10, praising Ueda's ability to blend surreal visuals and intuitive mechanics into a narrative that felt intimate and groundbreaking, evoking a dreamlike quality rarely achieved in contemporary titles.[55] Retrospective analyses have affirmed Ico's enduring appeal, with pieces noting how its mechanics and aesthetics have aged gracefully compared to more mechanics-heavy peers. For instance, a 2021 examination described the game as a "minimalist masterclass in cinematic and emotional storytelling," emphasizing its restraint as a timeless counterpoint to evolving industry trends.[9] This perspective underscores Ico's influence in prioritizing player interpretation over explicit exposition. In the context of 2000s gaming, Ico represented a shift toward minimalism in narrative delivery, contrasting sharply with the era's verbose, cutscene-driven epics like Final Fantasy X or Metal Gear Solid 2. Ueda's approach, rooted in Japanese concepts like ma (negative space), favored implication and player agency to evoke themes of isolation and connection, challenging the dominant trend of overloaded storytelling and setting a precedent for subtler, more introspective designs.[56][57]Awards and Recognition

Ico garnered significant recognition from major industry awards shortly after its 2001 release, particularly for its innovative gameplay mechanics, artistic design, and narrative approach. At the 2nd Annual Game Developers Choice Awards in 2002, the game won honors for Excellence in Level Design and Excellence in Visual Arts, while receiving nominations for Game of the Year, Original Game Character of the Year, and Excellence in Game Design.[58] The 5th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, now known as the D.I.C.E. Awards and presented by the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences, also celebrated Ico with wins in Art Direction and Character or Story Development categories in 2002, highlighting its aesthetic and storytelling achievements.[59] These accolades underscored the game's pioneering minimalistic storytelling and environmental integration, setting it apart in an era dominated by more action-oriented titles. The game has also earned enduring recognition in retrospective rankings, appearing consistently in Edge magazine's lists of the greatest video games since 2001. For instance, it ranked 13th in the magazine's 2007 edition of the top 100 games of all time, praised for its emotional depth and architectural beauty.[60]Legacy and Impact

Influence on Gaming

Ico's emphasis on exploration, minimalistic puzzle-solving, and atmospheric traversal of vast, empty environments contributed to the evolution of games focused on emotional immersion and contemplative pacing over traditional action mechanics. This approach, where player movement and interaction with the world convey narrative progression without heavy reliance on combat or objectives, foreshadowed later titles that prioritize spatial discovery. The game's innovative companion AI, exemplified by the player's relationship with Yorda, influenced subsequent designs emphasizing emotional bonds between characters. Naughty Dog drew directly from Ico to develop companion mechanics in The Last of Us, where AI-driven interactions between Joel and Ellie build trust and vulnerability through subtle, responsive behaviors rather than scripted events.[61] Similarly, Josef Fares cited Ico as a key inspiration for Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, praising its ability to evoke emotions via interdependent character dynamics and viewing it as proof that games could prioritize relational depth over conventional gameplay.[20] Ico's use of environmental storytelling—conveying backstory and themes through architecture, lighting, and subtle visual cues without explicit dialogue—has shaped indie games that favor ambiguity and player interpretation. This technique has influenced discussions on minimalist world-building to foster unease and discovery. The game's artistic ambitions contributed to a broader shift toward experiential titles in the AAA space while inspiring studios like thatgamecompany, whose works such as Journey share Ico's surreal aesthetics drawn from Giorgio de Chirico and focus on emotional journeys over plot-driven action.[62] Academic analyses in game studies highlight Ico's "narrative economy," where sparse elements maximize player agency and emotional investment, influencing discussions on interactivity and storytelling in 2010s journals.[63]Remasters and Re-releases

In 2011, Ico was remastered in high definition as part of The Ico & Shadow of the Colossus Collection for the PlayStation 3, developed by Bluepoint Games and published by Sony Computer Entertainment.[64] This bundle included both Ico and Shadow of the Colossus on a single Blu-ray disc, with enhancements such as native 720p resolution (upscaled to 1080p), widescreen support, a stable 30 frames per second framerate, stereoscopic 3D compatibility, and full 7.1 surround sound.[65] The remaster also introduced PlayStation Network trophy support, allowing players to earn achievements not present in the original PlayStation 2 version.[64] The collection was released on September 27, 2011, in North America, marking the first official HD update for Ico and improving visual clarity while preserving the original's atmospheric design.[64] Compared to the 2001 PlayStation 2 release, which ran at a low 512x224 resolution and 30 frames per second with occasional interlacing, the PS3 version offered sharper textures, better anti-aliasing via MLAA, and adjusted field of view in cutscenes for modern displays.[65] As of 2025, no native ports of Ico exist for PlayStation 4, PlayStation 5, or personal computers, though the PS3 remaster is accessible via cloud streaming on these platforms through a PlayStation Plus Premium subscription.[66] Fan-driven efforts, such as HD texture packs for the PCSX2 emulator, have enabled enhanced play on PC by overlaying improved visuals on the original ROM, though these remain unofficial and require ownership of the game.[65]Connections to Team Ico Works

Ico serves as the inaugural title in the informal "Team Ico trilogy" developed under the direction of Fumito Ueda at Sony's Japan Studio, followed by Shadow of the Colossus in 2005 and The Last Guardian in 2016.[67] This loose trilogy reflects Ueda's vision of interconnected storytelling through environmental narrative and player-driven experiences, with each game building on the previous one's core ideas of isolation and partnership.[68] The games share recurring motifs, including young male protagonists navigating ancient, crumbling worlds alongside enigmatic companions, encounters with mythical creatures, and deliberately ambiguous endings that invite interpretation. In Ico, the horned boy protagonist forms a bond with the ethereal Yorda, echoing the rider-companion dynamic in Shadow of the Colossus and the boy-Trico relationship in The Last Guardian. Ueda has noted these elements as intentional threads, such as the horned figures symbolizing outcasts across the titles, fostering thematic continuity around themes of sacrifice and fleeting connections without explicit lore ties.[68] Ueda's directorial approach evolved from Ico's minimalist design—emphasizing sparse dialogue, puzzle-solving, and emotional immersion on a modest budget—to the expansive, action-oriented scale of Shadow of the Colossus and the technically ambitious AI-driven companionship in The Last Guardian, enabled by increasing resources at Sony. This progression highlights Ueda's commitment to "design by subtraction," prioritizing player agency and subtle storytelling over overt mechanics, even as production scopes grew.[69] Team Ico, the development unit led by Ueda since 1997, effectively dissolved in 2011 when Ueda departed Sony Computer Entertainment, though he continued as a contractor to complete The Last Guardian.[70] Post-departure, Ueda founded the independent studio genDESIGN in 2014, collaborating with partners like Epic Games on new projects that extend his signature style of introspective, creature-focused adventures. In December 2024, genDESIGN announced their next untitled project—codenamed Project Robot—at The Game Awards, an adventure game published by Epic Games Publishing that continues Ueda's emphasis on emotional narratives and unique creature interactions.[71][72][73]References

- https://strategywiki.org/wiki/ICO/Controls