Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

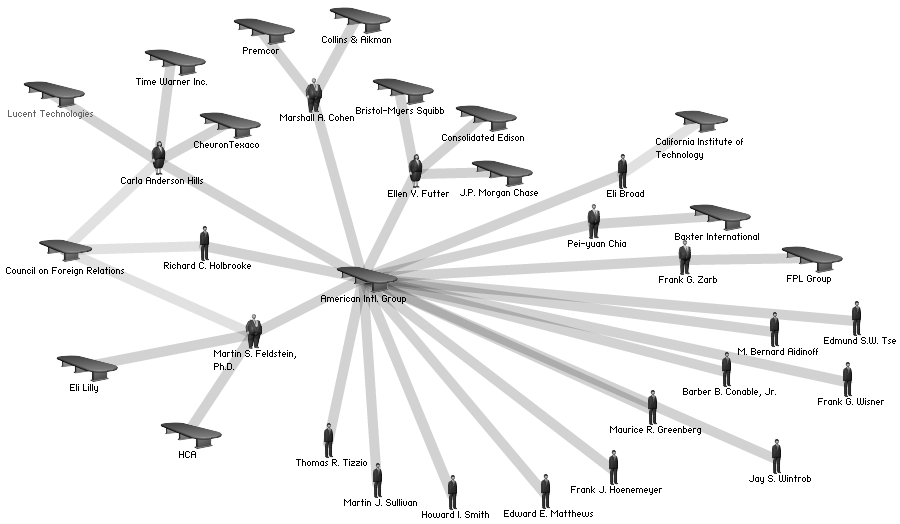

Interlocking directorate

View on Wikipedia

Two or more corporations have interlocking directorates when they share members of their boards of directors or each shares directors with a third firm. A person that sits on multiple boards is known as a multiple director.[1] Two firms have a direct interlock if a director or executive of one firm is also a director of the other, and an indirect interlock if a director of each sits on the board of a third firm.[2]

This practice, although widespread and lawful, raises questions about the quality and independence of board decisions. In the United States, antitrust law prohibits interlocking directorates within the same industry over collusion concerns, though legal observers have noted that this has long been unenforced.[3][4] In 2022, the Department of Justice signaled it would enforce laws on anti-competitive interlocking directorates, leading to the resignation of seven directors at five companies in October 2022.[4]

Socio-political importance

[edit]According to some observers,[who?] interlocks allow for cohesion, coordinated action, and unified political-economic power of corporate executives. They allow corporations to increase their influence by exerting power as a group, and to work together towards common goals.[5] They help corporate executives maintain an advantage, and gain more power over workers and consumers, by reducing intra-class competition and increasing cooperation.[2][6] In the words of Scott R. Bowman, interlocks "facilitate a community of interest among the elite of the corporate world that supplants the competitive and socially divisive ethos of an earlier stage of capitalism with an ethic of cooperation and a sense of shared values and goals."[7]

Interlocks act as communication channels, enabling information to be shared between boards via multiple directors who have access to inside information for multiple companies.[1] The system of interlocks forms what Michael Useem calls a "transcorporate network, overarching all sectors of business".[8] Interlocks have benefits over trusts, cartels, and other monopolistic/oligopolistic forms of organization, due to their greater fluidity, and lower visibility (making them less open to public scrutiny).[5] They also benefit the involved companies, due to reduced competition, increased information availability for directors, and increased prestige.[2][9]

Some theorists believe that because multiple directors often have interests in firms in different industries, they are more likely to think in terms of general corporate class interests, rather than simply the narrow interests of individual corporations.[7][10][11] Also, these individuals tend to come from wealthy backgrounds, socialize with the upper classes, and tend to have worked their way up the corporate hierarchy, making it more likely that they have internalized values that will cause them to personally support policies that are beneficial to business in general.[7]

Furthermore, multiple directors tend to be more frequently appointed to government positions, and sit on more non-profit/foundation boards than other directors. Thus, these individuals (known as the "inner circle" of the corporate class) tend to contribute disproportionately to the policy-planning and government groups that represent the interests of the corporate class,[12][13] and are the ones that are most likely to deal with general policy issues and handle political problems for the business class as a whole.[14] These individuals and the people around them are often considered to be the "ruling class" in modern politics. However, they do not wield absolute power, and they are not monolithic, often differing on which policies will best serve the interests of the upper classes.[15]

Interlocks not only occur between corporations, but also between corporations and non-profit institutions such as foundations, think tanks, policy-planning groups, and universities.[16][17] They can also be seen as a subset of connections in a larger upper class social network which includes all of the aforementioned types of institutions as well as elite social clubs, schools, resorts, and gatherings.[18][19] Multiple directors are "roughly twice as likely as single directors to be in the Social Register, to have attended a prestigious private school, or to belong to an elite social club."[20]

Modern interlock networks

[edit]Analyses of corporate interlocks have found a high degree of interconnectedness amongst large corporations.[21][22] It has also been shown that inbound interlocks (i.e. a network link from external firms into a focal firm) have a much greater impact and importance than outbound interlocks, a finding that laid the foundation for further research on inter-organizational networks based on overlapping memberships and other linkages such as joint ventures and patent backward and forward citations.[23] Virtually all large U.S. corporations are linked together in a network of interlocks.[24] Most corporations are within 3 or 4 "steps" from each other within this network.[21] Approximately 15–20% of all directors sit on two or more boards.[12]

The largest corporations tend to have the most interlocks, and also tend to have interlocks with each other, placing them at the center of the network.[25] Major banks, in particular, tend to be at the center of the network and have large numbers of interlocks.[26][27][28] With the globalization of financial capital following World War II, multinational interlocks have become progressively more common.[29] As the Cold War escalated, well-connected members of the CIA harnessed these interconnections to launder money through front foundations, as well as more substantial institutions such as the Ford Foundation.[30] A relatively small number of individuals—a few dozen—bind this multinational network together by participating in transnational interlocks and sitting on the boards of multiple global policy groups (such as the Council on Foreign Relations).[31]

Legality

[edit]In the United States, Section 8 of the Clayton Act prohibits interlocking directorates by U.S. companies competing in the same industry, if those corporations would violate antitrust laws if combined into a single corporation. However, at least 1 in 8 of the interlocks in the United States are between corporations that are supposedly competitors.[32]

Recent reinvigoration of enforcement

[edit]In 2022, the Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division signaled it would reinvigorate enforcement against anti-competitive interlocking directorates after decades of dormant enforcement.[3] In October 2022, it was reported that antitrust scrutiny brought on by Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter led to the resignation of seven directors from the boards of five companies.[4] According to Bloomberg News, private equity firms including Blackstone Inc. and Apollo Global Management are currently under federal interlocking directorate scrutiny.[33]

1970 graphs

[edit]In 1979 Levin and Roy reported[34] on interlocking directors at 797 corporations in 1970 where the board of directors ranged from 3 to 47 members, with a mean size of 13. Only 18% of the 8623 directors were on more than one board, though the mean number of interlockers for a corporation was 8. The components of the graph were 62 isolated boards, four pairs of corporations interlocked by one or more directors, a triad of interlocked corporations, and the greater component of 724 corporations. For an arbitrary pair of corporations in this component the median path length was 3. Levin and Roy tested the graph for cut points and failed to find any with their search starting with corporations with large boards.

In a study of clustering in the graph, Levin and Roy demonstrated the use of a bipartite graph with corporations listed on one side and directors with multiple seats on the other. The clusters become evident in a physical model using elastic bands and paper clips. The directors and corporations are listed arbitrarily to begin and the elastic bands placed as edges of the bipartite graph. Then a perusal of the elastics may suggest a re-ordering on one side or the other with the elastics slightly less tense. After some iteration this procedure reveals a cluster structure in the bipartite graph.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Scott, 1997: p. 7

- ^ a b c Salinger, 2005: p. 438

- ^ a b Demblowski, Denis (November 4, 2022). "DOJ Is Shaking Up World of Interlocking Directorates". Bloomberg Law. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ a b c "U.S. says seven board directors resigned under antitrust pressure". Reuters. 2022-10-19. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ a b Salinger, 2005: p. 437

- ^ Mizruchi, Mark S.; Schwartz, Michael (1992). Intercorporate relations: the structural analysis of business. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-43794-3.

- ^ a b c Bowman, 1996: p. 21

- ^ Useem, 1986: p. 53

- ^ Dogan, Mattéi (2003). Elite configurations at the apex of power. BRILL. p. 200. ISBN 978-90-04-12808-8.

- ^ Beder, Sharon (2006). Suiting themselves: how corporations drive the global agenda. Earthscan. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-84407-331-3.

- ^ Barrow, Clyde W. (1993). Critical Theories of State: Marxist, Neo-Marxist, Post-Marxist. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-299-13714-7.

- ^ a b Domhoff, 2006: pp. 30-31

- ^ Knoke, David (1994). Political networks: the structural perspective. Cambridge University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-521-47762-8.

- ^ Fennema, M. (1982). International networks of banks and industry. Springer. p. 208. ISBN 978-90-247-2620-2.

- ^ Zweig, Michael (2001). The working class majority: America's best kept secret. Cornell University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8014-8727-9.

- ^ Bowman, 1996: p. 22

- ^ Sklair, Leslie (2001). The Transnational Capitalist Class. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-631-22462-4.

- ^ Asimakopoulos, John (2009). "Globally Segmented Labor Markets". Critical Sociology. 35 (2): 175–198. doi:10.1177/0896920508099191. S2CID 145514921.

- ^ Domhoff, 2006: Chapter 3

- ^ Ackerman, Frank (2000). The political economy of inequality. Island Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-55963-798-5.

- ^ a b Domhoff, 2006: p. 26

- ^ Krantz, Matt (2002-11-24). "Web of board members ties together Corporate America". USA Today.

- ^ Johannes M Pennings, 1980. Interlocking Directorates: San Francisco: Jossey Bass

- ^ Slaughter, Sheila; Rhoades, Gary (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy: markets, state, and higher education. JHU Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-8018-7949-4.

- ^ Domhoff, 2006: p. 27

- ^ Devine, Fiona (1997). Social class in Ameriontent-Type: multipart/form-datagh University Press. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-7486-0666-5.

- ^ Mintz, Beth & Sia.org; hidegeonoticeCampusAmbasite book (1987). The Power Structure of American Business. University of Chicago Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-226-53109-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Glasberg, Davita Silfen (1989). The power of collective purse strings: the effects of bank hegemony on corporations and the state. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-520-06489-8.

- ^ Scott, 1997: pp. 18-19

- ^ Saunders, Frances Stonor (1999). The cultural cold war : the CIA and the world of arts and letters ([New ed.]. ed.). New York: New Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 1-56584-596-X.

Farfield was by no means exceptional in its incestuous character. This was the nature of power in America at this time. The system of private patronage was the pre-eminent model of how small, homogenous groups came to defend America's—and, by definition, their own—interests. Serving at the top of the pile was every self-respecting WASP's ambition. The prize was a trusteeship on either the Ford Foundation or the Rockefeller Foundation, both of which were conscious instruments of covert US policy, with directors and officers who were closely connected to, or even members of American intelligence.

- ^ Carroll, William K.; Carson, Colin (2006). "Neoliberalism, capitalist class formation and the global network of corporations and policy groups". In Plehwe, Dieter; Walpen, Bernhard; Neunhöffer, Gisela (eds.). Neoliberal hegemony: a global critique. Taylor & Francis. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-415-37327-2.

- ^ Wardrip-Fruin, Noah; Montfort, Nick (2003). New Media Reader. MIT Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-262-23227-2.

- ^ Nylen, Leah; Lim, Dawn (October 28, 2022). "Private Equity Firms Probed by US on Overlapping Board Seats". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2022-11-04.

- ^ Joel H. Levin & William H. Roy (1979) "A study of interlocking directorates", pp 349–78 in Perspectives on Social Network Research, editors: Paul W. Holland & Samuel Leinhardt, Academic Press ISBN 9780123525505

- Bowman, Scott R. (1996). The modern corporation and American political thought: law, power, and ideology. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01473-9.

- Domhoff, G. William (2006). Who Rules America?: Power, Politics, and Social Change. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-287625-5.

- Salinger, Lawrence M. (2005). Encyclopedia of white-collar and corporate crime. Vol. 1. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-3004-4.

- Scott, John (1997). Corporate Business and Capitalist Classes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-828075-0.

- Useem, Michael (1986). The Inner Circle: Large Corporations and the Rise of Business Political Activity in the U.S. and U.K.. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504033-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Domhoff, G. William (August, 2005); Interlocking Directorates in the Corporate Community.

- Mizruchi, Mark S. (August, 1996); "What Do Interlocks Do? An Analysis, Critique, and Assessment of Research on Interlocking Directorates". Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 22: 271–298.

- Phillips, Peter S. (June 24, 2005) "Big Media Interlocks with Corporate America".

- Scott, John (1990). The Sociology of Elites, Volume 3: Interlocking directorships and corporate networks. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-1-85278-392-1.

External links

[edit]- TheyRule.net Archived 2023-02-16 at the Wayback Machine—tool for mapping out board interlocks between large corporations, foundations, nonprofits, and universities, using data from SEC filings

Interlocking directorate

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Core Concepts

Formal Definition

An interlocking directorate exists when the same individual serves simultaneously as a director on the boards of two or more corporations, thereby establishing direct personal and informational connections between those entities.[5] This structure facilitates the flow of strategic insights, resource coordination, and governance practices across firms, often analyzed in corporate governance and network theory as a mechanism for interorganizational influence.[6] In the context of U.S. antitrust law, interlocking directorates are formally addressed and restricted under Section 8 of the Clayton Act of 1914, which states: "No person shall, at the same time, serve as a director or officer in any two corporations (other than banks, banking associations, and trust companies) that are... competitors, so that the elimination of competition by agreement between such corporations would constitute a violation of any of the antitrust laws."[7] This prohibition applies only to corporations engaged in commerce with combined capital, surplus, and undivided profits exceeding specified thresholds—$41,034,000 for each corporation as adjusted for inflation effective January 1, 2024—aiming to preempt anticompetitive coordination without requiring proof of actual harm.[8] Exceptions include temporary interlocks of up to one year for curative purposes or where the competitive overlap is de minimis, typically less than 20% of overlapping revenues in the line of commerce.[9] Economically, interlocking directorates can manifest in non-competitive settings, such as between suppliers and customers or across industries, where they are not per se illegal but may raise governance concerns regarding director independence and potential conflicts of interest under stock exchange rules like NYSE Section 303A, which limits the number of public company boards on which a director may serve to no more than four without justification.[5] Empirical studies in organizational sociology quantify interlocks by measuring the density of shared directors relative to total possible connections, revealing patterns of elite cohesion in large corporations; for instance, analyses of Fortune 500 firms have shown average board interlock rates fluctuating between 0.5 and 1.5 per firm in recent decades, influenced by regulatory pressures and governance reforms.[10]Types of Interlocks

Interlocking directorates are primarily classified into horizontal and vertical types based on the economic relationship between the connected firms. Horizontal interlocks arise when an individual serves as a director on the boards of two or more corporations operating in the same industry or market, potentially facilitating coordination among competitors.[11][12] Such arrangements have drawn antitrust scrutiny under Section 8 of the Clayton Act (1914), which prohibits them between firms with substantial competitive overlap to prevent collusion risks, though enforcement has historically focused on cases where interlocked firms hold significant market shares exceeding $10 million in capital or assets as of recent thresholds. Vertical interlocks, by contrast, connect firms at different stages of a supply chain, such as a manufacturer and its supplier or distributor, where a shared director may influence procurement, pricing, or resource allocation without directly implicating horizontal competition.[11][12] These are generally permissible under U.S. antitrust law, as they do not typically raise the same collusion concerns, though they can enable preferential treatment or information flows that affect market dynamics; empirical studies from the 1970s onward indicate vertical ties often serve resource dependence motives rather than anticompetitive ends.[13][14] A further distinction exists between direct and indirect interlocks. Direct interlocks involve a single individual simultaneously holding directorships at multiple firms, creating immediate overlap in governance.[5] Indirect interlocks occur when two firms are linked through a third entity, such as each sharing a director with an intermediary board, forming a chain that propagates influence across networks without pairwise overlap.[5] This typology, rooted in network analysis, highlights how indirect ties can amplify connectivity in corporate elites, with data from U.S. Fortune 500 firms in the 1970s showing indirect interlocks comprising up to 20-30% of total linkages in dense sectors like manufacturing.[15] Financial interlocks represent a specialized category, often overlapping with horizontal or vertical forms, where directors from banks or financial institutions sit on non-financial corporate boards, centralizing capital flows and monitoring.[6] Historical analyses of U.S. data from 1935-1970 reveal banks as hubs in interlock networks, with financial directors linking industrial firms to enhance lending oversight, though such ties declined post-1980s deregulation amid governance reforms.[16] These types are not mutually exclusive, and their prevalence varies by jurisdiction; for instance, European studies post-2000 emphasize vertical and financial ties in diversified conglomerates, contrasting U.S. emphasis on horizontal risks.[17]Distinction from Other Network Forms

Interlocking directorates, characterized by individuals serving on multiple corporate boards, form networks primarily through personal governance roles rather than direct financial or contractual mechanisms. Unlike ownership networks, where ties arise from equity stakes or shareholdings that confer control rights, interlocking directorates create linkages via shared directors without necessitating ownership overlap; empirical studies show that while interlocks may correlate with ownership concentration in certain contexts, such as insider systems, they operate independently as channels for information exchange and influence absent formal capital ties.[18][19] In contrast to strategic alliance networks, which involve explicit contractual agreements like joint ventures or partnerships for collaborative activities, board interlocks represent informal, individual-based connections that do not require mutual consent between firms but emerge from director appointments; these interlocks facilitate resource dependence resolution or elite cohesion without the legal obligations or durability of alliances, often modeled as bipartite affiliation networks linking firms and directors in a two-mode structure.[17][20] Board interlocks also diverge from transactional networks, such as supply chains or trade linkages, by operating at the strategic governance level rather than operational exchanges; whereas supply chain ties emphasize material or service flows governed by market contracts, interlocks enable monitoring, norm diffusion, and tacit coordination among executives, with network analyses revealing distinct centrality patterns like degree or eigenvector measures that highlight power asymmetries not captured in purely economic transaction graphs.[14][21] Furthermore, interlocking directorates differ from broader social or communication networks by their formal institutional embedding within corporate bylaws and regulatory frameworks, such as antitrust scrutiny under the Clayton Act, which targets potential collusion risks absent in informal personal acquaintances; this formality distinguishes them from ad hoc elite interactions, as interlocks are verifiable through public filings and sustain ties over director tenures, typically spanning years.[5][22]Historical Origins and Evolution

Pre-20th Century Precedents

The earliest instances of interlocking directorates in the United States emerged in the 1790s amid the incorporation of New England manufacturing firms, particularly textile mills financed and directed by overlapping subgroups of affluent investors who held positions on multiple boards to manage shared ownership interests.[23] These arrangements facilitated coordination among local elites in nascent industrial ventures, predating widespread corporate expansion. By 1816, interlocking extended to financial institutions, with New York City's 10 largest banks and 10 largest insurance companies forming a dense network of shared directorships that linked their governance structures.[23] This pattern intensified over subsequent decades; in 1836, nearly all of the 20 largest banks, 10 largest insurance firms, and 10 largest railroads interconnected via common directors, yielding a single elite network where 12 entities maintained 11 to 26 interlocks each, 10 held 6 to 10, and 16 had 1 to 5.[23] A prominent example occurred in 1845 with the Boston Associates, a cadre of approximately 80 men who directed 31 textile companies—accounting for 20% of national textile output—while simultaneously serving on boards controlling 40% of Boston's banking capital, 20 insurance firms, and 11 railroads, thereby centralizing influence across sectors.[23] Such interlocks enabled major capitalists to align business strategies and resource allocation without formal mergers. In the latter half of the 19th century, railroads became a focal point for interindustry interlocks, with analyses of major firms from 1886 to 1905 revealing a core structure dominated by rail, telegraph, and coal enterprises that peripherally connected to other industries, enhancing stability and coordination among owners during rapid expansion and consolidation.[24] By 1896, surveys of large American corporations documented prevalent interlocks across industrials, utilities, railroads, and banks, with 68% of the top 100 industrials, 50 utilities, and 25 railroads sharing directors with at least one other major entity, underscoring the mechanism's role in pre-antitrust era governance.[25][26] These precedents laid groundwork for later regulatory scrutiny, as shared directorships often served to harmonize competitive pressures among interlocking firms.Antitrust Era Foundations (1910s-1930s)

The Progressive Era's antitrust movement increasingly viewed interlocking directorates as a subtle mechanism for coordinating corporate behavior among rivals, bypassing the overt trusts targeted by the Sherman Act of 1890. Investigations revealed how shared board members enabled informal influence over pricing, production, and market allocation without formal agreements. The Pujo Committee's 1912-1913 probe into the "money trust" exposed a concentrated financial elite controlling vast resources through 341 interlocking directorships linking major banks like J.P. Morgan & Co. to railroads, utilities, and industrials, facilitating dominance without outright mergers.[27][28] These disclosures fueled legislative action, with reformers like Louis Brandeis decrying interlocks as "the root of many evils" that undermined competition by prioritizing financiers' interests over independent corporate governance.[29] Section 8 of the Clayton Antitrust Act, signed into law on October 15, 1914, directly addressed this by barring any individual from simultaneously serving as a director or officer in two competing corporations engaged in commerce, provided at least one had capital, surplus, and undivided profits exceeding $1 million—a threshold capturing most significant firms at the time.[30] The provision's preventive design aimed to dismantle potential channels for collusion ex ante, supplementing the Sherman Act's reactive prohibitions, though it exempted banks and allowed a one-year grace period for divestiture.[31] Enforcement in the 1910s and 1920s remained sporadic, with the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice prioritizing larger merger challenges over routine interlock scrutiny, reflecting the era's focus on structural remedies amid post-World War I economic expansion. By the 1930s, amid the Great Depression, renewed investigations confirmed interlocks' endurance: a National Resources Committee report documented pervasive networks, with 225 of the 250 largest non-financial corporations linked through shared directors, often across non-competitive sectors but raising concerns about broader power concentration.[2] These findings, alongside Temporary National Economic Committee hearings, reinforced Section 8's foundational role in antitrust doctrine, though lax thresholds and evidentiary hurdles limited dissolutions, establishing interlocks as a persistent regulatory target rather than an eradicated practice.[32]Post-World War II Expansion and Regulation

Following World War II, the United States experienced rapid economic growth and corporate expansion, which facilitated a proliferation of interlocking directorates among large firms. By the mid-1960s, the density of interlocks had increased compared to the pre-war era; among the top 250 industrial corporations, only 17 firms lacked any interlocks in 1965, versus 25 in 1935.[33] This expansion was driven by the rise of conglomerates, the professionalization of corporate governance, and the need for boards to access diverse expertise amid postwar industrialization and globalization of capital flows.[34] Interlocks often linked industrial firms to financial institutions, with banks and insurance companies serving as central nodes in these networks, enabling resource sharing and strategic coordination.[35] Regulatory scrutiny intensified in response to fears that such interlocks could facilitate anticompetitive behavior, though enforcement under Clayton Act Section 8 remained limited prior to this period. The U.S. Department of Justice initiated more systematic investigations after 1945, marking the first major postwar cases against interlocks.[36] In 1950, Congress amended Section 8 to broaden its scope by prohibiting not only directors but also officers elected or chosen by the board from serving in competing firms, while raising the jurisdictional threshold from $1 million to $10 million in combined capital, surplus, and undivided profits to focus on larger entities.[31] This adjustment aimed to balance antitrust concerns with practical exemptions for smaller firms, reflecting postwar priorities to curb potential collusion without stifling business efficiency. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) conducted key empirical studies underscoring the prevalence of interlocks. A 1951 FTC staff report examined director overlaps among the 1,000 largest manufacturing corporations, revealing extensive ties, particularly between nonfinancial firms and banks, which comprised over half of all interlocks identified.[35] These findings highlighted how financial institutions dominated interlock networks, potentially concentrating influence, though the report noted that many interlocks involved non-competitive firms.[35] Despite such documentation, prosecutions were rare; the FTC and DOJ prioritized mergers and other antitrust violations, viewing interlocks as symptomatic rather than primary threats, with only sporadic enforcement actions through the 1960s.[36] This era's regulatory framework thus emphasized monitoring over aggressive prohibition, allowing interlocks to persist as a governance tool amid economic dynamism.Economic Rationale and Benefits

Resource Mobilization and Expertise Sharing

Interlocking directorates facilitate resource mobilization by enabling firms to access external assets and reduce environmental dependencies, consistent with resource dependence theory. According to this framework, organizations appoint shared directors to co-opt elements of their environment, thereby securing critical inputs such as financing, supplier relationships, and market intelligence that might otherwise be uncertain or contested.[37] For instance, received interlocks allow firms to influence tied-to entities, mobilizing support like preferential loans or partnerships, while sent interlocks aid in environmental scanning for strategic resources.[38] Empirical analyses indicate that such ties correlate with improved cash holdings substitution through bank loans in emerging markets, where interlocks signal credibility to lenders.[39] Shared directors also promote expertise sharing by serving as conduits for tacit knowledge and best practices across firms. These individuals transfer managerial insights, such as operational efficiencies or technological approaches, that are difficult to codify formally.[14] In strategic settings, interlocks emerge when firms disclose private information like costs, enabling mutual monitoring and adoption of superior practices without explicit collusion.[14] Empirical evidence supports these mechanisms' positive outcomes, particularly in innovation. Chen et al. (2024) analyzed U.S. firms using exogenous variation from conflicting shareholder meeting schedules as an instrument for interlock formation, finding that board interlocks significantly increase patent quantity, quality (measured by citations), economic value, and relatedness to prior innovations through inter-firm knowledge spillovers.[40] The effects were stronger with directors possessing relevant experience and weaker with over-busy boards, highlighting expertise transfer as a causal channel. Similarly, studies in telecommunications and finance sectors demonstrate interlocks' role in diffusing governance and operational expertise, enhancing firm adaptability.[14] These benefits extend to resource pooling in networks, where interlocks broaden access to funding and alliances, though outcomes vary by tie directionality and firm context.[38]Monitoring and Governance Enhancements

Interlocking directorates facilitate enhanced board monitoring by enabling directors to leverage diverse experiences and external benchmarks from multiple firms, thereby improving oversight of executive management and reducing agency costs. Directors serving on several boards gain comparative insights into industry practices, strategic decision-making, and performance metrics, which strengthen their ability to evaluate and challenge internal management effectively.[41] This cross-pollination of knowledge addresses principal-agent problems by aligning director incentives more closely with shareholder interests through heightened vigilance and informed scrutiny.[42] Empirical research supports these governance benefits, particularly for executive directors holding outside positions, which correlate with superior board monitoring and decision-making quality. For instance, a study of Australian firms found that such interlocks contribute to more effective internal controls and risk assessment, as directors apply lessons from one board to mitigate opportunism in another.[43] Similarly, analysis of board interlocks in audit contexts reveals that well-connected directors elevate overall board efficacy, leading to more rigorous financial oversight and reduced audit risks. In competitive industries, interlocks promote governance enhancements by fostering director independence and expertise sharing without necessarily compromising competition, as evidenced by improved firm-level indicators like return on assets in networked structures.[4] However, these advantages depend on the quality of interlocked directors; antitrust interventions removing experienced interlockers have been shown to impair governance, underscoring the value of such networks in maintaining robust oversight.[3] Overall, while not universally beneficial, interlocking directorates demonstrably augment monitoring when they introduce high-caliber, informed perspectives to boards.Empirical Evidence of Positive Outcomes

A meta-analysis of 56 empirical studies encompassing 121 correlations demonstrates an overall positive association between board interlocks and firm financial performance, with the effect persisting across various national cultures, though moderated negatively by higher power distance and restraint (low indulgence).[44] This synthesis underscores interlocks' role in resource access and information sharing, benefits that hold despite contextual variations.[44] In the U.S. restaurant industry, analysis of 405 firm-year observations from publicly traded companies (1993–2019) reveals a positive main effect of board interlocks on Tobin's q, a market-based performance measure, with the relationship strengthened by geographic diversification as firms leverage interlocks for external resources amid expansion challenges.[45] Such findings align with resource dependence theory, where interlocks facilitate critical expertise and legitimacy in uncertain environments.[45] Evidence from Chinese A-share listed firms (2007–2022) indicates that greater centrality in the interlocking directorate network correlates with improved firm performance, particularly for younger enterprises and those facing financial constraints, attributable to enhanced information flows and resource mobilization.[46] A policy-induced reduction in interlocks, via resignations of government-affiliated directors in 2013, temporarily depressed performance, especially among non-state-owned entities, further supporting causality in these benefits.[46] Board interlocks also promote corporate innovation through knowledge spillovers, as evidenced by exogenous variation in connections due to shareholder meeting conflicts; interlocked firms exhibit higher patent quantities, qualities (e.g., forward citations), values, and relevance to prior innovations, with effects amplified by directors' youth and expertise but diminished by busy or outsider-heavy boards.[40] This mechanism highlights interlocks' value in transferring technical insights across firms, yielding focused, high-impact outputs.[40] Contingency-based models integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives, tested on 145 Italian firms, show positive performance impacts from interlocks when firms face resource scarcity or low ownership concentration, enabling better monitoring and external linkages without exacerbating agency conflicts.[47] These outcomes depend on power dynamics and firm-specific factors, illustrating targeted governance enhancements rather than uniform effects.[47]Anticompetitive Risks and Empirical Critiques

Mechanisms of Potential Collusion

Interlocking directorates among competing firms create potential channels for the exchange of competitively sensitive information, such as pricing strategies, production costs, and market plans, which could enable tacit or explicit coordination to soften rivalry.[22][48] These shared directors serve as conduits for monitoring competitors' internal decisions, reducing the informational asymmetries that typically sustain vigorous competition and lowering the coordination costs required for collusive equilibria.[49][2] In practice, such interlocks may align managerial incentives across firms, discouraging aggressive innovations or price cuts that could erode joint profits, as directors balance fiduciary duties with knowledge of rivals' responses.[50] For instance, investor-affiliated directors, who often hold financial stakes in multiple competitors, can leverage organizational touchpoints to synchronize business practices, potentially leading to higher prices and reduced product variety.[50][51] Empirical evidence illustrates these mechanisms in concentrated sectors; in Italian banking prior to a 2011 reform banning interlocks, shared directors facilitated less dispersed loan rates indicative of collusion, resulting in rates 14 basis points higher than post-reform levels, with greater reductions in markets featuring high pre-reform bank concentration.[49][52] Similarly, analyses of U.S. firms have linked horizontal interlocks to diminished competitive intensity, including avoidance of direct market confrontations.[50] However, broader studies across European cartel cases reveal few prior interlocking ties among convicted colluders, indicating that these mechanisms infrequently translate into detectable anticompetitive outcomes, possibly due to legal deterrents or alternative collusion facilitators like trade associations.[48][53] This suggests that while interlocks theoretically ease collusion by embedding rivals within each other's governance, actual facilitation remains context-dependent and rare in aggregate.[54]Concentration of Economic Power

Interlocking directorates enable the concentration of economic power by allowing a limited cadre of individuals to oversee and influence the operations of numerous major corporations, thereby centralizing strategic decision-making and resource allocation within elite networks. This mechanism fosters aligned interests among ostensibly independent entities, potentially diminishing market dispersion and enhancing the leverage of interconnected boards over broader economic sectors. Empirical network analyses demonstrate that such interlocks form dense clusters where high-centrality nodes—often comprising financial institutions and multinational firms—wield outsized control, as evidenced by global datasets encompassing 400,000 firms linked through 1,700,000 shared directorships, revealing persistent centrality rankings that amplify the dominance of core players in corporate governance.[55] In the United States, historical scrutiny by the Temporary National Economic Committee (TNEC), initiated in June 1938 under Senate Resolution 217, explicitly targeted interlocks as contributors to economic concentration, with Monograph No. 29 (1941) detailing how banking sector interlocks facilitated stockholdings and directorial overlaps that consolidated influence over investment activities and industrial control. The TNEC's findings underscored that these arrangements, prevalent among commercial banks and non-financial corporations, enabled a handful of directors to shape policies across industries, exacerbating power imbalances amid the Great Depression's aftermath, though wartime disruptions curtailed comprehensive enforcement recommendations.[56][57] Sector-specific evidence reinforces this pattern; for instance, in the Italian insurance market, studies of interlocking linkages among top firms reveal correlations between directorial overlaps and elevated Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) measures of concentration, where shared board members insulate dominant players from entry by smaller competitors, sustaining oligopolistic structures. Similarly, in banking, interlocks have been linked to softened competitive pressures, as shared directors facilitate tacit coordination on lending rates and market shares, with a 2015 Italian regulatory ban on bank interlocks leading to measurable increases in loan pricing variability indicative of prior homogenization.[58][52] Critics of mainstream antitrust narratives, drawing from causal analyses, argue that while interlocks correlate with concentration metrics like HHI exceeding 2,500 in affected industries, the causal pathway often involves informational efficiencies rather than overt collusion, yet the net effect remains a redistribution of economic agency toward a networked minority, as quantified by eigenvector centrality scores in global interlock graphs where top 1% of nodes control pathways to over 80% of network value in key economies. This centralization raises causal concerns for democratic economic pluralism, as dispersed ownership gives way to boardroom hegemony, though empirical critiques note that post-2008 regulatory scrutiny has modestly reduced interlock density in finance without dismantling underlying power cores.[55][3]Studies Showing Limited or No Harm

Empirical investigations into the anticompetitive effects of interlocking directorates have often yielded findings of limited or negligible harm to competition. A seminal study by Peter Dooley in 1969 analyzed interlocking patterns among 250 large U.S. corporations and found that while interlocks were more common between firms of comparable size, they did not correlate strongly with industry concentration levels or other indicators of reduced rivalry, suggesting no substantial facilitation of collusion.[33] Similarly, Pfeffer and Salancik's 1978 resource dependence theory posited that interlocks primarily serve to stabilize environmental uncertainty through information exchange and cooptation rather than explicit coordination on prices or output, with their review of data indicating no significant influence on competitive behaviors like pricing decisions.[59] Subsequent research has reinforced these conclusions, highlighting the scarcity of direct evidence linking interlocks to measurable anticompetitive outcomes. For instance, a 1983 study by Donald Palmer examined broken interlocks and intercorporate coordination, concluding that the dissolution of ties did not lead to observable shifts in firm strategies or market conduct that would imply prior collusive restraint, implying limited causal impact from ongoing interlocks. Mizruchi's 1996 comprehensive review in the Annual Review of Sociology assessed decades of interlocking research and noted that while theoretical risks exist, empirical tests frequently failed to demonstrate consistent effects on firm performance metrics tied to competition, such as profit rates or market shares, attributing many observed patterns to social rather than economic coordination. In specific sectors, studies have isolated even weaker associations. An analysis of banking interlocks in regulated environments found no significant effect on loan pricing or credit allocation attributable to shared directors, with variations in interlock density explaining less than 1% of pricing variance after controlling for firm-specific factors.[13] Regulatory reviews, including those by the Antitrust Modernization Commission in 2007, echoed this by observing that prohibitions on minor interlocks—those involving firms with under 2% market overlap—serve little purpose absent evidence of harm, as data showed no correlation with elevated concentration or softened competition in such cases. These findings collectively indicate that while interlocks may enable information flows, they rarely translate into verifiable reductions in competitive vigor, prompting critiques that antitrust concerns are often presumptive rather than evidence-based.Legal and Regulatory Framework

Clayton Act Section 8 Provisions

Section 8 of the Clayton Act, enacted on October 15, 1914, prohibits any person from simultaneously serving as a director or officer of two competing corporations engaged in commerce, where such service could substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly, unless specific exemptions apply.[7] This provision targets structural links that might facilitate anticompetitive coordination without requiring proof of actual harm, aiming to prevent opportunities for collusion among rivals. The law excludes banks, banking associations, and trust companies, which are governed by separate banking regulations under the Clayton Act itself.[7] The prohibition applies only to corporations meeting jurisdictional thresholds: each must have capital, surplus, and undivided profits exceeding $41,000,000 (as adjusted for 2024; thresholds are revised annually for inflation by the FTC).[60] Additionally, the interlock is actionable if competitive sales between the corporations exceed certain de minimis levels: either corporation's competitive sales must be less than $4,201,000 (2024 threshold), or if both exceed that amount, the interlock is permitted only if competitive sales constitute less than 2% of the smaller corporation's total sales or less than 4% of each corporation's total sales. These safe harbors recognize that minor overlaps pose negligible risks to competition.[61] Enforcement of Section 8 falls to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ), with violations treated as misdemeanors punishable by fines up to $5,000 or imprisonment up to one year, or both; equitable remedies like injunctions are also available to unwind interlocks.[7] The statute's per se approach—barring interlocks based on potential rather than demonstrated effects—reflects early 20th-century concerns over concentrated corporate power, though courts have occasionally required evidence of competitive overlap beyond mere industry classification.[62] Exemptions do not apply if the interlock violates other antitrust laws, ensuring Section 8 complements broader prohibitions under Sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act.[7]Historical Enforcement Patterns

Section 8 of the Clayton Act, enacted on October 15, 1914, prohibited interlocking directorates between competing corporations to preempt anticompetitive coordination, but enforcement remained sporadic in the initial decades following its passage.[31] Early judicial interpretations under the Sherman Act, such as United States v. E.C. Knight Co. (1895), limited federal reach into corporate structures, contributing to under-enforcement of Section 8 until the mid-20th century.[63] The first significant government challenges emerged in 1953 with United States v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., which construed Section 8's prohibitions, and United States v. W.T. Grant Co., which clarified that director resignations do not moot ongoing violations, establishing key precedents for proving competitive overlap.[31] Enforcement activity intensified in the 1960s and 1970s, as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) employed computational methods to identify interlocks systematically, leading to increased investigations and consent orders resolving alleged violations without litigation.[31] During this period, both the FTC and Department of Justice (DOJ) pursued a campaign against interlocks, often securing director resignations or structural remedies in industries like retail and manufacturing, though few cases reached full adjudication on the merits.[63] By the 1980s, patterns shifted toward private enforcement actions supplementing government efforts, with the Supreme Court in BankAmerica Corp. v. United States (1983) acknowledging a prior 60-year enforcement gap while upholding Section 8's application to bank-insurance interlocks.[64] Overall, government filings numbered in the dozens across these decades, punctuated by bursts of scrutiny rather than sustained litigation.[63] Post-1980s, enforcement declined markedly, with Section 8 invoked primarily in merger reviews rather than standalone actions, reflecting broader antitrust retrenchment and the 1990 amendments that introduced de minimis thresholds (e.g., competitive sales below approximately $1 million exempt) and raised interlocking prohibitions to firms with over $10 million in capital or assets.[31][65] The FTC's last major pre-2020s probe occurred in 2009 against Apple and Google directors, resolved via resignations without formal decrees.[31] From the 1990s onward, standalone cases were rare, with agencies securing fewer than a handful of public resolutions annually, often through informal director removals rather than court orders, amid perceptions of limited empirical harm from interlocks.[66] This dormancy persisted until 2022, when DOJ announcements of resignations signaled renewed focus, though historical patterns underscore enforcement's characterization as "punctuated by a few bursts of mild activity and then followed by long periods of benign neglect."[63][67]Thresholds and Exemptions

Section 8 of the Clayton Act, codified at 15 U.S.C. § 19, imposes prohibitions on interlocking directorates and officers only where both competing corporations meet a minimum size threshold, defined as capital, surplus, and undivided profits aggregating more than $10,000,000 per corporation.[7] This base threshold is adjusted annually by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to account for changes in the gross national product, as mandated by amendments under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976.[68] For fiscal year 2025, the adjusted threshold is $51,380,000 per corporation.[68] Interlocks below this size for either corporation fall outside the statute's jurisdictional reach, regardless of competitive overlap.[62] The statute further exempts certain interlocks through de minimis exceptions based on the scale of competitive sales, even if both corporations exceed the capital threshold.[7] These exemptions apply if: (1) the competitive sales of either corporation are less than $5,138,000 (the 2025 adjusted value from the $1,000,000 base); (2) the competitive sales of each corporation are less than 2 percent of that corporation's total sales; or (3) the competitive sales of one corporation are less than 2 percent of its total sales while the other corporation's competitive sales are less than $5,138,000.[68][62] These de minimis thresholds are also adjusted annually by the FTC and reflect an intent to avoid prohibiting interlocks with negligible potential for anticompetitive effects.[68] Banks, banking associations, and trust companies are categorically exempt from the directorate interlock prohibitions under Section 8(a), though officer interlocks remain subject to scrutiny if they could substantially lessen competition.[7] For officers under Section 8(b), an additional safe harbor exists if the positions held do not enable the individual to participate in formulating policy or affect competitive decisions, providing flexibility beyond pure size-based thresholds.[7] Violations of these provisions are per se illegal once thresholds are met and exemptions inapplicable, with civil penalties up to $50,000 per day enforceable by the FTC or Department of Justice.[62]Contemporary Enforcement and Developments

Post-2020 Reinvigoration

Following the change in U.S. presidential administration in January 2021, antitrust enforcers at the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) intensified scrutiny of interlocking directorates under Section 8 of the Clayton Act, marking a departure from prior decades of limited proactive enforcement. This reinvigoration aligned with broader Biden administration priorities to address perceived concentrations of economic power, including an "extensive review" of interlocks across sectors by the DOJ Antitrust Division.[69][70] The DOJ led initial efforts, announcing on October 19, 2022, that seven directors had resigned from the boards of five public companies to resolve concerns over potentially unlawful interlocks between competitors.[67] Subsequent DOJ actions included five additional director resignations from four corporate boards on March 9, 2023, alongside one private equity firm declining a board appointment rights exercise.[71] Further resignations followed in August 2023, reflecting a pattern of informal resolutions via director departures rather than litigation.[72] The FTC complemented these moves with its first standalone Section 8 enforcement consent agreement since the 1980s on August 16, 2023, prohibiting an individual from serving as a director on competing life sciences firms' boards.[3] In September 2023, the FTC secured resignations of three directors from the board of Sevita, a behavioral health provider, amid investigations into interlocks with rival entities.[73] These actions emphasized proactive monitoring, public tips, and sector-specific probes, such as in private equity and healthcare.[74] Empirical data indicate the enforcement surge reduced interlock prevalence: after the third quarter of 2022, directors of public companies were less likely to hold competitor board seats, suggesting deterrence effects without requiring court rulings.[3] Annual FTC adjustments to Section 8 thresholds—such as raising the competitive sales minimum to $4,921,000 effective February 2024—maintained the framework's applicability amid inflation but did not alter the prohibition's core scope.[75] Enforcement has persisted into 2025, with agencies urging board self-audits to preempt violations.[76]Sector-Specific Cases (e.g., Life Sciences, Tech)

In the life sciences sector, interlocking directorates have been documented at significant levels among public companies, with studies identifying overlaps that violate Section 8 of the Clayton Act by placing directors on boards of horizontal competitors. A 2024 analysis of 2,241 life sciences firms from 2003 to 2022 found that 10-20% of board members held interlocked positions at any given time, with the total number of such interlocks more than doubling over the period; these overlaps were concentrated in subsectors like biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, where firms compete in similar therapeutic areas, heightening risks of coordinated pricing or restrained innovation.[77] The study classified many interlocks as illegal per se, as they involved directors serving simultaneously on boards of entities with substantial competitive overlaps, without qualifying for de minimis exemptions based on asset or sales thresholds.[10] Such arrangements in life sciences have drawn regulatory scrutiny for potentially exacerbating market concentration and limiting patient access to therapies, as interlocked boards may facilitate information sharing on drug development pipelines or pricing strategies among rivals. In 2020, approximately 20% of public life sciences companies exhibited interlocking boards, according to a Stanford University study cited in congressional inquiries, prompting Senator Richard Durbin to urge the DOJ and FTC in February 2023 to investigate these networks for risks including higher drug prices and reduced therapeutic options.[78] While specific enforcement actions remain limited compared to other sectors, the FTC's post-2020 emphasis on Clayton Act violations has included broader health care probes that indirectly address interlock facilitation of anticompetitive conduct, such as in prescription drug markets.[79] In the technology sector, historical interlocks among major firms have prompted director resignations to avert antitrust challenges, illustrating enforcement against overlaps that could enable collusion in areas like software, hardware, and digital services. For instance, between 2006 and 2009, Google and Apple shared two directors—Eric Schmidt, then Google's CEO, and Arthur Levinson, formerly CEO of Genentech—who served on both boards amid direct competition in mobile operating systems and search technologies, leading to their departures following FTC and DOJ inquiries into potential Clayton Act violations.[2] More recently, in 2022, the DOJ prompted resignations from interlocked directors across tech-adjacent firms, including Udemy Inc. and Skillsoft Corp., competitors in online learning platforms, where shared board members risked synchronized strategies in edtech markets.[80] Tech interlocks often arise in high-growth areas like cloud computing and AI, where rapid innovation amplifies concerns over shared governance influencing competitive dynamics, though empirical evidence of harm remains debated. The FTC's 2023 consent order against an arrangement involving tech-related entities underscored risks of anticompetitive information exchanges via interlocks, even absent explicit collusion, by prohibiting future overlaps and mandating governance separations.[81] Overall, while tech enforcement has focused on voluntary resolutions rather than litigation, agencies have signaled continued vigilance, with 2025 updates to Clayton Act thresholds adjusting for inflation to capture evolving market sizes in digital sectors.[8]Global Comparisons

In the United States, Section 8 of the Clayton Act of 1914 explicitly prohibits interlocking directorates between competing corporations if their combined capital, surplus, and undivided profits exceed specified thresholds—$41,034,000 for each corporation as adjusted for inflation in 2023—unless exemptions apply for de minimis overlaps or pre-existing arrangements.[82] This per se rule aims to prevent information flows that could facilitate collusion, with enforcement historically lax until recent Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice scrutiny post-2020, targeting sectors like life sciences.[10] By contrast, the European Union lacks a specific statutory ban on horizontal interlocks, relying instead on Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to assess anticompetitive effects, such as collusion facilitation, on a case-by-case basis.[83] This effects-based approach has resulted in fewer dedicated enforcement actions compared to the US, though national variations exist; Italy, for instance, enacted targeted regulations in 2010 prohibiting interlocks in banking and finance to curb cross-ownership risks.[84] Empirical studies of 15 European countries reveal dense national interlocking networks, with international ties concentrated among larger firms in core economies like Germany and France, potentially amplifying coordinated behavior across borders without uniform prohibitions.[85] In Japan, interlocking directorates are integral to keiretsu business groups, comprising clusters of firms linked by cross-shareholdings, preferential trade, and shared board members, often centered around a main bank; these structures, persisting from post-World War II reforms, numbered around six major horizontal keiretsu as of 2023 and prioritize long-term stability over short-term competition.[86] Unlike US or EU antitrust frameworks, Japanese law under the Antimonopoly Act does not categorically ban such interlocks, viewing them as enhancing group cohesion and resilience against market shocks, though critics argue they entrench oligopolistic practices in industries like automobiles and electronics.[87] China exhibits high densities of interlocking directorates, particularly among state-owned enterprises listed on domestic exchanges, where social network analyses of over 1,500 firms from 2003–2012 identified central actors like government officials dominating ties, fostering information exchange but raising governance opacity concerns in a transitional economy.[21] Regulations under the Company Law and Anti-Monopoly Law scrutinize interlocks for competitive harm but prioritize state-directed coordination, with no per se prohibitions; studies link these networks to improved firm performance via resource sharing, though they correlate with reduced innovation in competitive sectors.[46] In emerging markets like India, the Competition Act of 2002 addresses interlocks through effects-based merger reviews and abuse prohibitions, but enforcement remains nascent, with 2024 analyses highlighting risks in concentrated sectors without dedicated board-level bans.[88]| Jurisdiction | Key Regulation | Approach to Horizontal Interlocks | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | Clayton Act §8 (1914) | Per se prohibition with thresholds/exemptions | Strict enforcement revival; targets competitor overlaps >$10M in sales.[66] |

| European Union | TFEU Article 101 | Effects-based assessment | No blanket ban; national variances (e.g., Italy's finance-specific rules).[89] |

| Japan | Antimonopoly Act (1947) | Permissive within keiretsu | Emphasizes stability; cross-shareholdings reinforce ties.[90] |

| China | Anti-Monopoly Law (2008) | Case-by-case with state oversight | Dense in SOEs; aids resource pooling but risks opacity.[91] |