Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Internet backbone

View on Wikipedia

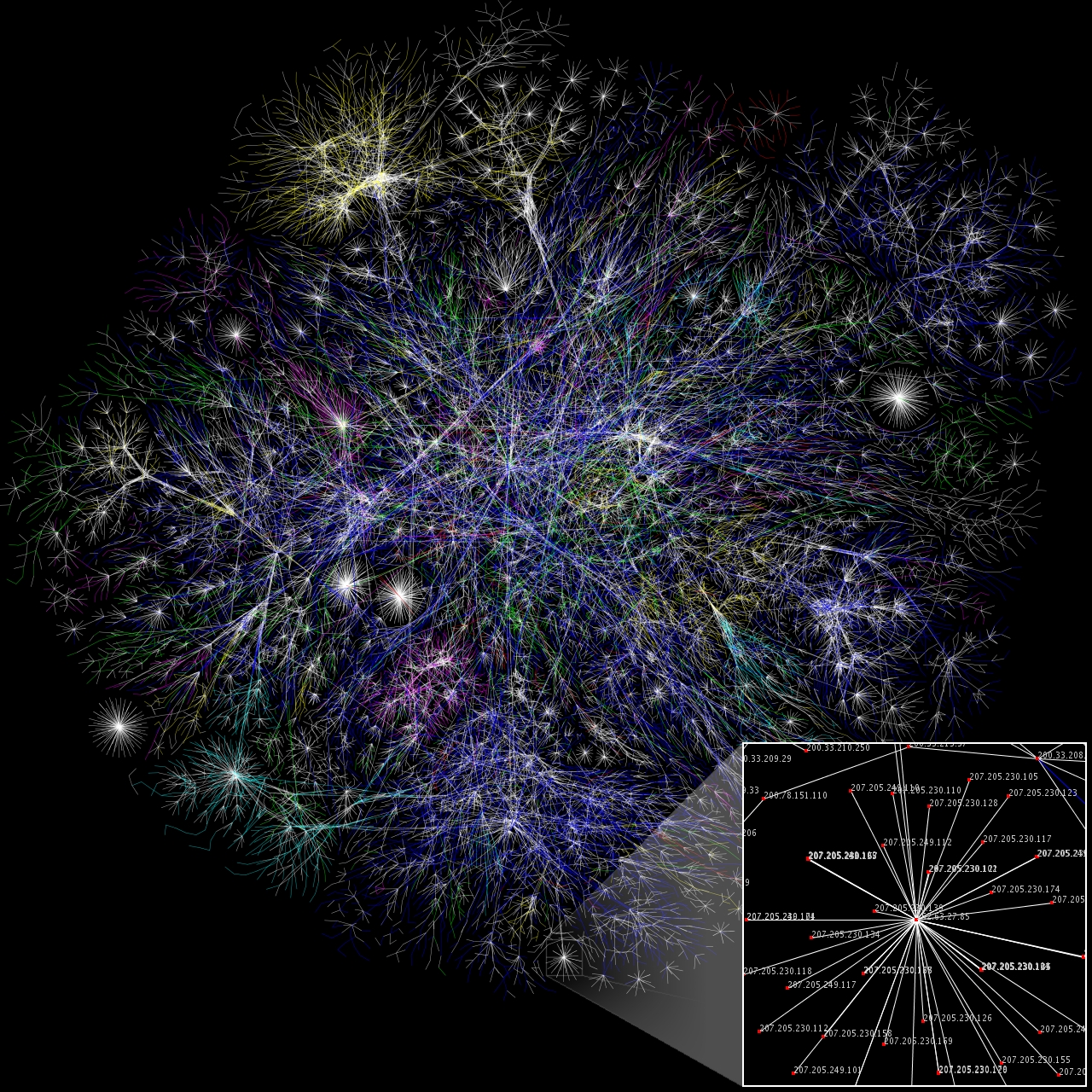

The Internet backbone is the principal data routes between large, strategically interconnected computer networks and core routers of the Internet. These data routes are hosted by commercial, government, academic and other high-capacity network centers as well as the Internet exchange points and network access points, which exchange Internet traffic internationally. Internet service providers (ISPs) participate in Internet backbone traffic through privately negotiated interconnection agreements, primarily governed by the principle of settlement-free peering.

The Internet, and consequently its backbone networks, do not rely on central control or coordinating facilities, nor do they implement any global network policies. The resilience of the Internet results from its principal architectural features, such as the idea of placing as few network state and control functions as possible in the network elements, instead relying on the endpoints of communication to handle most of the processing to ensure data integrity, reliability, and authentication. In addition, the high degree of redundancy of today's network links and sophisticated real-time routing protocols provide alternate paths of communications for load balancing and congestion avoidance.

The largest providers, known as Tier 1 networks, have such comprehensive networks that they do not purchase transit agreements from other providers.[1]

Infrastructure

[edit]

The Internet backbone consists of many networks owned by numerous companies.

Fiber-optic communication remains the medium of choice for Internet backbone providers for several reasons. Fiber-optics allow for fast data speeds and large bandwidth, suffer relatively little attenuation — allowing them to cover long distances with few repeaters — and are immune to crosstalk and other forms of electromagnetic interference.[citation needed]

The real-time routing protocols and redundancy built into the backbone is also able to reroute traffic in case of a failure.[2] The data rates of backbone lines have increased over time. In 1998,[3] all of the United States' backbone networks had utilized the slowest data rate of 45 Mbit/s. However, technological improvements allowed for 41 percent of backbones to have data rates of 2,488 Mbit/s or faster by the mid 2000s.[4]

History

[edit]The first packet-switched computer networks, the NPL network and the ARPANET were interconnected in 1973 via University College London.[5] The ARPANET used a backbone of routers called Interface Message Processors. Other packet-switched computer networks proliferated starting in the 1970s, eventually adopting TCP/IP protocols or being replaced by newer networks.

The National Science Foundation created the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNET) in 1986 by funding six networking sites using 56kbit/s interconnecting links, with peering to the ARPANET. In 1987, this new network was upgraded to 1.5Mbit/s T1 links for thirteen sites. These sites included regional networks that in turn connected over 170 other networks. IBM, MCI and Merit upgraded the backbone to 45Mbit/s bandwidth (T3) in 1991.[6] The combination of the ARPANET and NSFNET became known as the Internet. Within a few years, the dominance of the NSFNet backbone led to the decommissioning of the redundant ARPANET infrastructure in 1990.

In the early days of the Internet, backbone providers exchanged their traffic at government-sponsored network access points (NAPs), until the government privatized the Internet and transferred the NAPs to commercial providers.[1]

Modern backbone

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2011) |

Because of the overlap and synergy between long-distance telephone networks and backbone networks, the largest long-distance voice carriers such as AT&T Inc., Verizon, Sprint, and Lumen also own some of the largest Internet backbone networks. These backbone providers sell their services to Internet service providers.[1]

Each ISP has its own contingency network and is equipped with an outsourced backup. These networks are intertwined and crisscrossed to create a redundant network. Many companies operate their own backbones which are all interconnected at various Internet exchange points around the world.[7] In order for data to navigate this web, it is necessary to have backbone routers—routers powerful enough to handle information—on the Internet backbone that are capable of directing data to other routers in order to send it to its final destination. Without them, information would be lost.[8]

Economy of the backbone

[edit]Peering agreements

[edit]Backbone providers of roughly equivalent market share regularly create agreements called peering agreements, which allow the use of another's network to hand off traffic where it is ultimately delivered. Usually they do not charge each other for this, as the companies get revenue from their customers.[1][9]

Regulation

[edit]Antitrust authorities have acted to ensure that no provider grows large enough to dominate the backbone market. In the United States, the Federal Communications Commission has decided not to monitor the competitive aspects of the Internet backbone interconnection relationships as long as the market continues to function well.[1]

Transit agreements

[edit]Backbone providers of unequal market share usually create agreements called transit agreements, and usually contain some type of monetary agreement.[1][9]

Regional backbone

[edit]Egypt

[edit]During the 2011 Egyptian revolution, the government of Egypt shut down the four major ISPs on January 27, 2011 at approximately 5:20 p.m. EST.[10] The networks had not been physically interrupted, as the Internet transit traffic through Egypt was unaffected. Instead, the government shut down the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) sessions announcing local routes. BGP is responsible for routing traffic between ISPs.[11]

Only one of Egypt's ISPs was allowed to continue operations. The ISP Noor Group provided connectivity only to Egypt's stock exchange as well as some government ministries.[10] Other ISPs started to offer free dial-up Internet access in other countries.[12]

Europe

[edit]Europe is a major contributor to the growth of the international backbone as well as a contributor to the growth of Internet bandwidth. In 2003, Europe was credited with 82 percent of the world's international cross-border bandwidth.[13] The company Level 3 Communications began to launch a line of dedicated Internet access and virtual private network services in 2011, giving large companies direct access to the tier 3 backbone. Connecting companies directly to the backbone will provide enterprises faster Internet service which meets a large market demand.[14]

Caucasus

[edit]Certain countries around the Caucasus have very simple backbone networks. In 2011, a 75-year-old woman in Georgia pierced a fiber backbone line with a shovel and left the neighboring country of Armenia without Internet access for 12 hours.[15] The country has since made major developments to the fiber backbone infrastructure, but progress is slow due to lack of government funding. [citation needed]

Japan

[edit]Japan's internet backbone requires a high degree of efficiency to support high demand for the Internet and technology in general. Japan had over 104 million Internet users in 2024.[16] Since Japan has a demand for fiber to the home, Japan is looking into tapping a fiber-optic backbone line of NTT, a domestic backbone carrier, in order to deliver this service at cheaper prices.[17]

China

[edit]In some instances, the companies that own certain sections of the Internet backbone's physical infrastructure depend on competition in order to keep the Internet market profitable. This can be seen most prominently in China. Since China Telecom and China Unicom have acted as the sole Internet service providers to China for some time, smaller companies cannot compete with them in negotiating the interconnection settlement prices that keep the Internet market profitable in China. This imposition of discriminatory pricing by the large companies then results in market inefficiencies and stagnation, and ultimately affects the efficiency of the Internet backbone networks that service the nation.[18]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Greenstein, Shane. 2020. "The Basic Economics of Internet Infrastructure." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34 (2): 192-214. DOI: 10.1257/jep.34.2.192

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Jonathan E. Nuechterlein; Philip J. Weiser (2005). Digital Crossroads. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262140911.

- ^ Nuechterlein, Jonathan E., author. (5 July 2013). Digital crossroads: telecommunications law and policy in the internet age. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51960-1. OCLC 827115552.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kesan, Jay P.; Shah, Rajiv C. (2002). "Shaping Code". SSRN 328920.

- ^ Malecki, Edward J. (October 2002). "The Economic Geography of the Internet's Infrastructure". Economic Geography. 78 (4): 399–424. doi:10.2307/4140796. ISSN 0013-0095. JSTOR 4140796.

- ^ Kirstein, P.T. (1999). "Early experiences with the Arpanet and Internet in the United Kingdom" (PDF). IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 21 (1): 38–44. doi:10.1109/85.759368. ISSN 1934-1547. S2CID 1558618. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-07.

- ^ Kende, M. (2000). "The Digital Handshake: Connecting Internet Backbones". Journal of Communications Law & Policy. 11: 1–45.

- ^ Tyson, J. (3 April 2001). "How Internet Infrastructure Works". Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ Badasyan, N.; Chakrabarti, S. (2005). "Private peering, transit and traffic diversion". Netnomics: Economic Research and Electronic Networking. 7 (2): 115. doi:10.1007/s11066-006-9007-x. S2CID 154591220.

- ^ a b "Internet Backbone". Topbits Website. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- ^ a b Singel, Ryan (28 January 2011). "Egypt Shut Down Its Net With a Series of Phone Calls". Wired. Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Van Beijnum, Iljitsch (30 January 2011). "How Egypt did (and your government could) shut down the Internet". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Murphy, Kevin (28 January 2011). "DNS not to blame for Egypt blackout". Domain Incite. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ "Global Internet backbone back up to speed for 2003 after dramatic slow down in 2002". TechTrends. 47 (5): 47. 2003.

- ^ "Europe - Level 3 launches DIA, VPN service portfolios in Europe". Europe Intelligence Wire. 28 January 2011.

- ^ Lomsadze, Giorgi (8 April 2011). "A Shovel Cuts Off Armenia's Internet". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ "Digital 2024:Japan". DATAREPORTAL. Retrieved 2025-07-31.

- ^ "Japan telecommunications report - Q2 2011". Japan Telecommunications Report (1). 2011.

- ^ Li, Meijuan; Zhu, Yajie (2018). "Research on the problems of interconnection settlement in China's Internet backbone network". Procedia Computer Science. 131: 153–157. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2018.04.198.

Further reading

[edit]- Dzieza, Josh (2024-04-16). "The cloud under the sea: The invisible seafaring industry that keeps the internet afloat". The Verge. Retrieved 2024-04-16.

External links

[edit]Internet backbone

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Core Concept and Role

The Internet backbone consists of the high-capacity, interconnected networks operated by Tier 1 providers that form the core infrastructure for global data transmission, linking major regional networks and handling the majority of long-haul traffic.[8] These networks utilize high-speed fiber-optic cables and advanced routers to create redundant paths, ensuring efficient routing between distant endpoints without reliance on intermediary transit providers.[2] Tier 1 operators, including AT&T, Verizon, NTT, and Deutsche Telekom, maintain settlement-free peering agreements, allowing direct exchange of traffic at scale.[3] In its role, the backbone serves as the primary conduit for aggregating and distributing Internet traffic, enabling low-latency communication across continents by optimizing packet forwarding through protocols like Border Gateway Protocol (BGP).[2] It supports the Internet's decentralized architecture by interconnecting at Internet Exchange Points (IXPs), where multiple providers meet to offload traffic, thereby reducing costs and enhancing resilience against failures.[8] This core layer underpins scalability, as it absorbs exponential growth in data volumes—estimated at over 4.9 zettabytes globally in 2023—while maintaining performance for applications from web browsing to cloud services.[3] The backbone's design emphasizes redundancy and capacity, with submarine cables comprising a significant portion for international links, carrying approximately 99% of intercontinental data as of 2020.[2] By prioritizing high-bandwidth transmission over last-mile access networks, it ensures that end-user demands are met through efficient core operations, forming the essential framework for the Internet's operational integrity.[8]Architectural Position in the Internet

The Internet backbone forms the core layer of the global network architecture, consisting of high-capacity, long-haul transmission networks operated primarily by Tier 1 providers. These providers interconnect their infrastructures through settlement-free peering agreements at Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) and private peering facilities, enabling efficient transit of data across continents without reliance on paid upstream services. This positioning allows the backbone to aggregate and forward the bulk of inter-domain traffic, serving as the foundational conduit between disparate regional and national networks.[2][9][10] In the multi-tiered ISP hierarchy, the backbone resides at the apex, distinct from distribution and access layers that handle local connectivity and policy enforcement closer to end-users. Tier 1 networks, such as those operated by AT&T, Verizon, and NTT, maintain global reach and redundancy, utilizing protocols like Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) for dynamic route advertisement and selection across autonomous systems. This core architecture ensures scalability, with backbone links often exceeding terabit-per-second capacities on dense wavelength-division multiplexing (DWDM) systems over fiber-optic cables.[3][11][12] The backbone's role contrasts with edge-oriented components, such as content delivery networks (CDNs) and last-mile access providers, by focusing on undifferentiated, high-volume packet transport rather than user-specific optimization or caching. It handles approximately 70-80% of international Internet traffic via submarine cables and terrestrial trunks, prioritizing low-latency paths for critical applications while distributing load to prevent congestion. This central position underscores the Internet's decentralized yet hierarchically structured design, where backbone resilience directly impacts global connectivity reliability.[8][13][14]Historical Evolution

Origins in ARPANET and Early Networks (1960s-1970s)

The origins of the internet backbone lie in the invention of packet switching, a method for breaking data into discrete units for efficient, resilient transmission across networks. In 1960, Paul Baran at the RAND Corporation began exploring distributed communications to ensure survivability in the event of nuclear attack, proposing in internal memos the division of messages into small "message blocks" routed independently via multiple paths.[15] Baran formalized this in his 1964 multi-volume report On Distributed Communications Networks, advocating hot-potato routing where nodes forwarded blocks to the nearest available link, laying groundwork for decentralized network cores.[16] Independently, in 1965, Donald Davies at the UK's National Physical Laboratory developed a similar concept for a national data network, coining the term "packet switching" to describe data chunks of about 1,000 bits each, with protocols for assembly at destinations.[17] [18] These ideas gained traction through visionary planning at the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), established in 1958 following the Soviet Sputnik launch to advance military technologies.[19] J.C.R. Licklider, appointed head of ARPA's Information Processing Techniques Office (IPTO) in 1962, articulated a "Galactic Network" concept in a 1963 internal memo, envisioning interconnected computers enabling seamless human-machine symbiosis and resource sharing across distant sites.[20] Licklider's 1960 paper "Man-Computer Symbiosis" had earlier emphasized interactive computing, influencing ARPA's shift toward networked systems over isolated machines.[21] ARPANET emerged as the first implementation of these principles, designed as a wide-area packet-switched network to connect research institutions. In 1966–1967, ARPA issued requests for proposals on packet switching, selecting Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) in 1968 to build Interface Message Processors (IMPs)—minicomputers acting as the network's core switching nodes, each handling up to 256 kilobits per second across 50-kilobit telephone lines.[22] The first IMP arrived at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) on August 30, 1969, under Leonard Kleinrock's Network Measurement Center, marking the initial node of what would become the ARPANET backbone.[23] The inaugural inter-node transmission occurred on October 29, 1969, at 10:30 p.m. PDT, when UCLA student Charley Kline sent a message from an SDS Sigma 7 host to a Scientific Data Systems SDS-940 at Stanford Research Institute (SRI), successfully transmitting "LO" before the system crashed on the "G" of "LOGIN."[23] [24] By December 5, 1969, the network linked four nodes: UCLA, SRI, the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), and the University of Utah, with IMPs forming a rudimentary backbone that dynamically routed packets without dedicated end-to-end circuits. Expansion continued into the 1970s, reaching 15 nodes by mid-1971 and implementing the Network Control Protocol (NCP) in late 1970 for reliable host-to-host data transfer, while parallel efforts like Davies' NPL Mark I network (operational 1971) tested local packet switching with hex buses linking computers at 70 kilobits per second.[25] These early systems demonstrated the feasibility of core infrastructures prioritizing redundancy and shared access, foundational to modern backbones.[26]NSFNET Backbone and Academic Expansion (1980s)

In the early 1980s, the National Science Foundation (NSF) initiated a networking program to address the research community's need for access to advanced computational resources, building on prior efforts like ARPANET and CSNET while emphasizing supercomputing capabilities.[27] By 1985, NSF had funded the establishment of five supercomputer centers—located at Cornell University, the University of Illinois, Princeton University, the University of California San Diego, and NASA Ames Research Center—and outlined plans for a dedicated network to interconnect them, ensuring equitable access for academic researchers nationwide.[28] This initiative prioritized TCP/IP protocols for interoperability, extending beyond military-focused predecessors to foster broader scientific collaboration.[29] The NSFNET backbone became operational in 1986, initially operating at 56 kbit/s speeds across leased lines to link the five supercomputer centers, with additional nodes at key mid-level network hubs like those managed by Merit Network in Michigan.[30] Designed as a wide-area network for high-performance computing, it rapidly evolved into the de facto U.S. backbone for research traffic, interconnecting approximately 2,000 computers by late 1986 and enabling resource sharing among dispersed academic institutions.[29] NSF's "Connections" program further supported expansion by granting funds to universities and regional networks for direct attachment, promoting mid-level networks (e.g., BARRNET in California and PREP in Pennsylvania) as intermediaries between campus LANs and the backbone.[30] Rapid growth in usage—driven by email, file transfers, and remote supercomputer access—caused congestion on the initial infrastructure within months, prompting NSF to issue a 1987 solicitation for upgrades.[31] In 1988, under a cooperative agreement with Merit, Inc., IBM, and MCI, the backbone transitioned to T1 (1.5 Mbit/s) lines, forming a 13-node ring topology spanning major research sites from Seattle to Princeton, which dramatically increased capacity and accommodated surging academic demand.[32][33] This phase solidified NSFNET's role in academic expansion, connecting over 100 campuses by decade's end and laying groundwork for international links, while enforcing an "Acceptable Use Policy" restricting commercial traffic to preserve its research mandate.[34] By facilitating distributed computing and data exchange, NSFNET catalyzed interdisciplinary research, though its growth highlighted tensions between public funding and scalability limits that would influence later commercialization.[35]Commercial Transition and Global Growth (1990s-2000s)

The decommissioning of the NSFNET backbone on April 30, 1995, completed the shift from government-funded to commercial operation of the core U.S. Internet infrastructure. NSFNET, operational since 1986, had expanded to connect over 2 million computers by 1993 but faced unsustainable demand from burgeoning commercial traffic, doubling roughly every seven months by 1992.[29][36] To enable this transition, the National Science Foundation established four initial Network Access Points (NAPs) in 1994, managed by private firms including Sprint, MFS Communications, Pacific Bell, and Ameritech, which served as public interconnection hubs for regional and emerging commercial networks.[36] These NAPs, supplemented by private peering points like MAE-East (operational since 1992 and upgraded to FDDI by 1994), allowed providers such as MCI's internetMCI and SprintLink to absorb former NSFNET regional traffic without federal oversight.[36] The Telecommunications Act of 1996 accelerated privatization by deregulating local and long-distance markets, fostering competition among backbone operators and spurring massive infrastructure investments.[37] Early commercial backbones, upgraded from T1 (1.5 Mbps) in the late 1980s to T3 (45 Mbps) by 1991, saw capacity expansions that supported annual traffic growth of about 100% through the early 1990s, with explosive surges following the 1995 transition.[36][38] Tier 1 providers like AT&T, MCI, Sprint, and later Level 3 and Global Crossing emerged, peering directly to exchange traffic without transit fees, while the Routing Arbiter Project—deployed via route servers at NAPs by late 1994—standardized BGP routing policies to maintain stability amid this decentralization.[36][39] Global expansion intensified in the late 1990s and 2000s, as U.S. backbones interconnected with international links via submarine fiber-optic cables, which carried nearly all transoceanic data. The dot-com boom drove over $20 billion in investments for undersea systems, introducing wavelength-division multiplexing (WDM) from the 1990s to boost capacities from thousands to millions of simultaneous voice channels.[40][41] Key deployments included TAT-12 (1996, adding 80 Gbps transatlantic capacity) and TAT-14 (2000, with 3.2 Tbps initial lit capacity using dense WDM), alongside Asia-Pacific routes like APCN (1990s upgrades) and SEA-ME-WE 3 (1999), connecting Europe, Middle East, and Asia.[41] By the mid-2000s, these cables formed a mesh exceeding 1 million kilometers, enabling exponential international traffic growth and reducing latency for emerging e-commerce and content distribution.[42] This buildout, however, resulted in temporary overcapacity post-2001 bust, as demand lagged initial projections despite sustained doubling of global Internet traffic every 1-2 years.[43]Technical Components

Physical Infrastructure: Fibers, Cables, and Transmission

The physical infrastructure of the internet backbone relies on optical fiber cables to transmit data over vast distances at high speeds, using pulses of light propagated through glass or plastic cores.[44] These cables form the core network connecting continents and major population centers, with single-mode fibers predominant due to their narrow core diameter—typically 8-10 micrometers—that supports long-haul transmission with minimal signal dispersion.[45] Bundles of dozens to hundreds of such fibers are encased in protective sheathing, armoring, and insulation to withstand environmental stresses, enabling capacities exceeding hundreds of terabits per second per cable through dense wavelength division multiplexing (DWDM).[46] Submarine cables constitute a critical subset, spanning oceans to link international backbones and carrying over 99% of intercontinental data traffic.[47] As of 2024, the global submarine cable network totals approximately 1.4 million kilometers in length, with systems like the MAREA transatlantic cable achieving a capacity of 224 terabits per second (Tbps) via multiple fiber pairs and advanced modulation.[48][4] Aggregate subsea capacity surpasses 3 petabits per second (Pbps), driven by demand from cloud services and streaming, though actual lit capacity utilization remains a fraction due to incremental upgrades.[49] These cables employ repeaters every 50-100 kilometers to amplify optical signals using erbium-doped fiber amplifiers, compensating for attenuation in seawater.[47] Terrestrial fiber optic cables complement submarine links by interconnecting regional hubs, data centers, and cities within continents, often buried underground or strung along poles.[50] These routes form dense meshes in high-demand areas, such as North America and Europe, where fiber density supports latencies under 1 millisecond for intra-continental traffic.[51] DWDM technology enables transmission of up to 80-96 channels per fiber pair at 100-400 gigabits per channel, scaling backbone throughput without laying additional cables.[52] Coherent optics and forward error correction further enhance spectral efficiency, allowing modern systems to approach Shannon limits for error-free transmission over thousands of kilometers.[53] Transmission in backbone fibers operates primarily in the C-band (1530-1565 nm) for low-loss propagation, with L-band extensions for added capacity in long-haul scenarios.[54] Raman amplification supplements EDFAs in submarine environments to counter nonlinear effects like stimulated Brillouin scattering, ensuring signal integrity across spans exceeding 6,000 kilometers without regeneration.[55] Deployment costs for new cables range from $15,000 to $50,000 per kilometer, influenced by terrain and depth, underscoring the capital-intensive nature of backbone expansion.[56] Redundancy via diverse routing mitigates outages, as single cable failures can disrupt up to 10-20% of traffic on affected paths until rerouting completes.[50]Routing and Protocols: BGP and Core Operations

The Border Gateway Protocol version 4 (BGP-4), standardized in RFC 4271 and published in January 2006, functions as the foundational inter-autonomous system (AS) routing protocol for the internet backbone.[57] It enables ASes, particularly Tier 1 backbone providers, to exchange network reachability information in the form of IP prefixes, constructing global paths for data transit without reliance on centralized coordination. As a path-vector protocol, BGP includes the AS_PATH attribute in advertisements to document the sequence of ASes a route traverses, facilitating loop prevention through explicit checks for the advertising AS's prior presence in the path.[57] This design supports scalable, policy-oriented routing essential for the decentralized backbone, where operators prioritize commercial incentives over shortest-path metrics alone. Backbone core operations center on BGP peering sessions, predominantly external BGP (eBGP) between Tier 1 ASes, which exchange full routing tables exceeding 1 million IPv4 prefixes as of early 2025.[58] Sessions establish over TCP port 179 for reliability, initiating with OPEN messages that negotiate parameters including AS numbers, hold timers (default 180 seconds), and optional capabilities like route refresh.[57] KEEPALIVE messages, sent at intervals less than the hold time, sustain connectivity, while UPDATE messages announce new routes (with NLRI and path attributes such as NEXT_HOP, LOCAL_PREF, and communities) or withdraw unreachable prefixes via the WITHDRAW field. NOTIFICATION messages handle errors, such as malformed attributes or session cease, triggering teardown.[57] These exchanges propagate incrementally, with backbone routers filtering and applying outbound policies to align with peering agreements, ensuring only viable paths enter the global table. BGP's best-path selection algorithm, executed per prefix in the local routing information base (Loc-RIB), employs a deterministic, multi-step process to resolve multiple candidate routes.[57] It first discards infeasible paths (e.g., those with AS loop detection failures or unreachable next hops), then prefers the highest LOCAL_PREF (a non-transitive attribute set inbound to encode exit preferences, often favoring customer over peer routes in backbone hierarchies). Subsequent criteria include the shortest AS_PATH length, lowest origin code (IGP over EGP over incomplete), lowest MULTI_EXIT_DISC (MED) for same-AS exits, eBGP over iBGP, minimum interior gateway protocol (IGP) cost to the next hop, route age (oldest for stability), and lowest originating router ID.[57] This sequence, vendor-agnostic in core RFC terms though extended by implementations like Cisco's WEIGHT, permits fine-grained control, such as prepending AS_PATH to deter inbound traffic or using communities for conditional advertisement. In large backbone ASes, internal BGP (iBGP) disseminates eBGP-learned routes to non-border routers via route reflectors or confederations, avoiding full-mesh scalability issues while preserving AS_PATH integrity through non-modification of external attributes.[57] Policies applied via prefix-lists, AS_PATH regex, or attribute manipulation enforce settlement-free peering norms among Tier 1s, where default routes are absent and full tables are mandated for mutual reachability. BGP's attribute framework—well-known mandatory (e.g., AS_PATH, NEXT_HOP), optional transitive (e.g., communities for signaling), and non-transitive (e.g., LOCAL_PREF)—underpins traffic engineering, such as dampening unstable routes per RFC 2439 extensions or aggregating prefixes to curb table bloat.[57] These operations maintain backbone resilience, handling dynamic updates from events like link failures through rapid convergence, though reliant on operator vigilance for anomaly detection.[59]Internet Exchange Points and Interconnection Hubs

Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) serve as critical physical infrastructure in the internet backbone, enabling multiple autonomous systems operated by internet service providers (ISPs), content delivery networks (CDNs), and other entities to interconnect and exchange IP traffic directly through peering agreements.[60] These points facilitate efficient traffic routing by allowing networks to bypass upstream transit providers, thereby minimizing latency, reducing operational costs, and improving overall network resilience against failures in the backbone hierarchy.[61] IXPs emerged as essential hubs following the commercialization of the internet in the 1990s, evolving from early neutral meeting places like the Commercial Internet Exchange (CIX) established in 1991 to handle growing inter-network traffic volumes.[62] Technically, IXPs operate via a shared Layer 2 Ethernet switching fabric, where participating networks connect using high-speed ports and establish bilateral or multilateral Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) sessions over this common medium to announce routes and forward packets destined for each other's address spaces.[63] This setup supports both public peering, where any participant can connect to the switch and select peers via BGP, and route servers that simplify multilateral peering by aggregating announcements from multiple networks into a single BGP session per participant.[64] The Layer 2 nature ensures low-latency, high-bandwidth exchanges without the overhead of traversing the public internet or paid transit links, optimizing backbone efficiency for high-volume traffic such as inter-regional data flows.[65] Interconnection hubs, often co-located within major data centers, extend the IXP model by providing ecosystems for both public IXP access and private interconnections, including direct cross-connects between specific networks or cloud providers via dedicated fiber links.[66] These hubs concentrate backbone peering activity, with facilities like those operated by Equinix or DE-CIX hosting multiple IXPs and enabling hybrid connectivity models that integrate on-net caching, edge computing, and low-latency links essential for modern backbone operations.[67] For instance, DE-CIX's Frankfurt hub recorded a global peering traffic peak of nearly 25 terabits per second in 2024, reflecting the scale at which these points handle backbone-level exchanges amid surging data demands from streaming, cloud services, and IoT.[68] By aggregating diverse networks at strategic geographic locations, IXPs and interconnection hubs mitigate single points of failure in the backbone through redundant fabrics and diverse participant routing policies, while fostering competition that pressures transit pricing downward.[69] However, concentration in major hubs like those in Europe and North America raises resilience concerns, as disruptions—such as the 2024 DE-CIX power incident affecting 15% of European traffic—underscore vulnerabilities despite redundant designs.[70] Globally, over 600 active IXPs operate as of October 2025, with community-driven models in developing regions promoting local traffic retention to alleviate backbone strain from international transit dependencies.[71]Major Operators and Networks

Tier 1 Providers and Their Dominance

Tier 1 providers constitute the uppermost echelon of Internet service providers, defined as autonomous systems capable of reaching every other network globally through settlement-free peering arrangements exclusively, without reliance on paid IP transit from upstream entities. This status requires ownership or control of expansive infrastructure spanning continents and oceans, including direct interconnections at major Internet exchange points and participation in protocols like BGP for routing table exchanges. As of 2024, the number of true global Tier 1 networks remains limited, typically numbering between 9 and 12, reflecting the high barriers to entry involving massive capital investments in fiber optic cables, submarine systems, and router deployments.[72][3] Prominent Tier 1 providers encompass AT&T (AS7018), Verizon (AS701), Lumen Technologies (AS3356, incorporating former Level 3 assets), NTT Communications (AS2914), Tata Communications (AS6453), Arelion (AS1299), GTT Communications, Cogent Communications (AS174), Deutsche Telekom (AS3320), and PCCW Global (AS3491). These entities maintain peering policies that confirm their Tier 1 classification, often publicly documenting open interconnection terms to attract traffic exchange partners. For instance, Arelion's AS1299 has been ranked as the most interconnected backbone network based on peering density metrics from 2023 analyses. Ownership of key submarine cable consortia, such as those mapping global undersea routes, further solidifies their positional advantage in handling long-haul traffic.[10][73][74] The dominance of Tier 1 providers arises from their central role in aggregating and forwarding the bulk of inter-domain traffic, where they serve as the default any-to-any connectivity fabric for lower-tier networks that purchase transit services from them. Economically, settlement-free peering among Tier 1s minimizes operational costs compared to transit-dependent models, enabling competitive pricing for wholesale services while generating revenue through downstream sales. Technically, their dense mesh of interconnections—often exceeding thousands of peers—ensures low-latency paths and resilience against failures, as evidenced by BGP route announcements that propagate global reachability. In 2021, traditional backbone providers like Tier 1s still routed a substantial share of international bandwidth, though content delivery networks operated by hyperscalers have eroded some dominance by deploying private fiber and direct peering, capturing up to 69% of demand growth in cross-border data flows by bypassing public backbones.[9][75] This oligopolistic structure fosters stability in core routing but raises concerns over potential bottlenecks or policy influences, as Tier 1s control pivotal chokepoints like transatlantic and transpacific cable landings. Despite competitive pressures from cloud giants building proprietary networks—such as Google's Dunant cable operational since 2021—Tier 1s retain leverage through legacy infrastructure scale and regulatory compliance in licensed spectrum and rights-of-way, underpinning approximately 80-90% of conventional Internet traffic routing in peer-reviewed infrastructure studies. Their sustained preeminence is thus rooted in causal factors of sunk capital costs and network effects, where adding new Tier 1 entrants requires improbable scale to achieve universal peering acceptance.[76][75]Regional and Specialized Backbone Entities

Regional backbone entities primarily consist of Tier 2 Internet service providers (ISPs), which operate high-capacity networks within specific geographic areas or countries but rely on paid transit from Tier 1 providers for global connectivity.[3] These entities maintain their own fiber-optic infrastructure and peering arrangements to serve regional customers, including businesses and local ISPs, often achieving national coverage without full international independence. For instance, in the United States, providers like Comcast and Cox Communications deploy regional backbones spanning multiple states, interconnecting data centers and supporting traffic aggregation before handing off to global Tier 1 networks. In Europe, entities such as British Telecom's regional operations function similarly, focusing on intra-continental routing while purchasing upstream transit.[3] Specialized backbone entities, distinct from commercial Tier 2 providers, include national research and education networks (NRENs) designed for high-performance connectivity among academic, scientific, and governmental institutions. These networks prioritize low-latency, high-bandwidth links for data-intensive research, often featuring dedicated wavelengths and advanced protocols not typical in commercial backbones. In North America, Internet2 serves as a key example, connecting over 300 U.S. universities and labs with a hybrid fiber network capable of up to 400 Gbps on transatlantic links as of 2024 upgrades in collaboration with partners like CANARIE and GÉANT.[77] Similarly, ESnet, operated by the U.S. Department of Energy, provides specialized backbone services for scientific computing, linking national labs with petabyte-scale data transfers.[78] In Europe, GÉANT acts as a pan-regional specialized backbone, aggregating traffic from over 50 national NRENs and enabling international research collaborations with capacities exceeding 100 Gbps on core links.[79] Examples of constituent NRENs include JANET in the UK and SURFnet in the Netherlands, which deploy custom infrastructure for e-science applications like grid computing. In the Asia-Pacific, APAN coordinates specialized backbones across member countries, supporting advanced networking for astronomy and climate modeling projects.[80] In Latin America, RedCLARA interconnects regional NRENs, facilitating south-south research exchanges with peering to global counterparts. These specialized entities often operate on non-commercial models, funded by governments or consortia, emphasizing resilience and innovation over profit.[81]Economic Framework

Peering Versus Transit: Agreements and Incentives

Peering involves the direct interconnection of two networks, typically autonomous systems (ASes), to exchange traffic destined solely for each other's customers, often under settlement-free terms where neither party pays the other. This arrangement contrasts with IP transit, in which a customer network pays a upstream provider for access to the full Internet routing table, enabling reachability to all destinations beyond the provider's own customers.[82][83] Settlement-free peering predominates among large backbone operators, reflecting balanced mutual benefits, while transit serves as a commoditized service for smaller or asymmetric networks seeking comprehensive connectivity.[84] Peering agreements, whether public at Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) or private bilateral links, commonly enforce criteria such as traffic ratio balance—often capped at 2:1 or 3:1—to prevent one network from subsidizing the other's growth—and minimum traffic volumes or network quality thresholds to justify infrastructure costs. Violations, such as sustained imbalance, can trigger renegotiation to paid peering, where the higher-traffic sender compensates the receiver, or depeering, as seen in disputes involving content-heavy networks exceeding traditional balance norms. Transit contracts, by comparison, are volume-based purchases priced per megabit (e.g., $0.50–$5 per Mbps in 2023 regional markets, declining with scale), with service level agreements (SLAs) guaranteeing uptime and performance but offering less routing control to the buyer.[85][86][87]| Aspect | Peering (Settlement-Free) | Transit |

|---|---|---|

| Cost Structure | No direct payment; shared infrastructure costs | Paid per bandwidth unit; commoditized pricing |

| Scope | Limited to peers' customers; partial Internet reach | Full Internet access via provider's upstreams |

| Performance | Lower latency (direct hops); customizable routing | Variable, dependent on provider's paths |

| Requirements | Balanced ratios, quality metrics; mutual evaluation | Minimal; contract-based, no balance needed |