Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

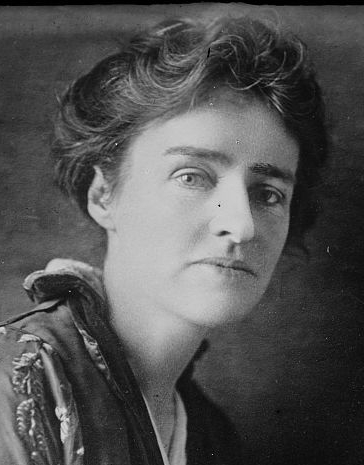

Jean Webster

View on Wikipedia

Jean Webster was the pen name of Alice Jane Chandler Webster (July 24, 1876 – June 11, 1916), an American author whose books include Daddy-Long-Legs and Dear Enemy. Her best-known books feature lively and likeable young female protagonists who come of age intellectually, morally, and socially, but with enough humor, snappy dialogue, and gently biting social commentary to make her books palatable and enjoyable to contemporary readers.

Key Information

Childhood

[edit]Alice Jane Chandler Webster was born in Fredonia, New York. She was the eldest child of Annie Moffet Webster and Charles Luther Webster. She lived her early childhood in a strongly matriarchal and activist setting, with her great-grandmother, grandmother and mother all living under the same roof. Her great-grandmother worked on temperance issues and her grandmother on racial equality and women's suffrage.[1]

Alice's mother was niece to Mark Twain, and her father was Twain's business manager and subsequently publisher of many of his books by Charles L. Webster and Company, founded in 1884. Initially, the business was successful and, when Alice was five, the family moved to a large brownstone in New York, with a summer house on Long Island. However, the publishing company ran into difficulties, and increasingly the relationship with Mark Twain deteriorated. In 1888, her father had a breakdown and took a leave of absence, and the family moved back to Fredonia. He subsequently committed suicide in 1891 from a drug overdose.[1]

Alice attended the Fredonia Normal School and graduated in 1894 in china painting. From 1894 to 1896, she attended the Lady Jane Grey School, 269 Court Street in Binghamton as a boarder. The specific address of the school has been a mystery.[2][3] During her time there, the school taught academics, music, art, letter-writing, diction and manners to about 20 girls. The Lady Jane Grey School inspired many of the details of the school in Webster's novel Just Patty, including the layout of the school, the names of rooms (Sky Parlour, Paradise Alley), uniforms, and the girls' daily schedule and teachers. It was at the school that Alice became known as Jean. Since her roommate was also called Alice, the school asked if she could use another name. She chose "Jean", a variation on her middle name. Jean graduated from the school in June 1896 and returned to the Fredonia Normal School for a year in the college division.[1]

College years

[edit]In 1897, Webster entered Vassar College as a member of the class of 1901. Majoring in English and economics, she took a course in welfare and penal reform and became interested in social issues.[1] As part of her course she visited institutions for "delinquent and destitute children".[4] She became involved in the College Settlement House that served poorer communities in New York, an interest she would maintain throughout her life. Her experiences at Vassar provided material for her books When Patty Went to College and Daddy-Long-Legs. Webster began a close friendship with the future poet Adelaide Crapsey who remained her friend until Crapsey's death in 1914.[1]

She participated with Crapsey in many extracurricular activities, including writing, drama, and politics. Webster and Crapsey supported the socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs during the 1900 presidential election, although as women they were not allowed to vote. She was a contributor of stories to the Vassar Miscellany[4] and as part of her sophomore year English class, began writing a weekly column of Vassar news and stories for the Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier.[1] Webster reported that she was "a shark in English" but her spelling was reportedly quite eccentric, and when a horrified teacher asked her authority for a spelling error, she replied "Webster", a play on the name of the dictionary of the same name.[1][4]

Webster spent a semester in her junior year in Europe, visiting France and the United Kingdom, but with Italy as her main destination, including visits to Rome, Naples, Venice and Florence. She traveled with two fellow Vassar students, and in Paris met Ethelyn McKinney and Lena Weinstein, also Americans, who were to become lifelong friends. While in Italy, Webster researched her senior economics thesis "Pauperism in Italy". She also wrote columns about her travels for the Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier and gathered material for a short story, "Villa Gianini", which was published in the Vassar Miscellany in 1901. She later expanded it into a novel, The Wheat Princess. Returning to Vassar for her senior year, she was literary editor for her class yearbook and graduated in June 1901.[1]

Adult years

[edit]Back in Fredonia, Webster began writing When Patty Went to College, in which she described contemporary women's college life. After some struggles finding a publisher, it was issued in March 1903 to good reviews. Webster started writing the short stories that would make up Much Ado about Peter, and with her mother visited Italy for the winter of 1903–1904, including a six-week stay in a convent in Palestrina, while she wrote the Wheat Princess. It was published in 1905.[1]

The following years brought a further trip to Italy and an eight-month world tour to Egypt, India, Burma, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Hong Kong, China and Japan with Ethelyn McKinney, Lena Weinstein and two others, as well as the publication of Jerry Junior (1907) and The Four Pools Mystery (1908).[1]

Jean Webster began an affair with Ethelyn McKinney's brother, Glenn Ford McKinney. A lawyer, he had struggled to live up to the expectations of his wealthy and successful father. Mirroring a subplot of Dear Enemy, he had an unhappy marriage due to his wife's struggling with mental illness; McKinney's wife, Annette Reynaud, frequently was hospitalized for manic-depressive episodes. The McKinneys' child, John, also showed signs of mental instability. McKinney responded to these stresses with frequent escapes on hunting and yachting trips as well as alcohol abuse; he entered sanatoriums on several occasions as a result. The McKinneys separated in 1909, but in an era when divorce was uncommon and difficult to obtain, they were not divorced until 1915. After his separation, McKinney continued to struggle with alcoholism but had his addiction under control in the summer of 1912 when he traveled with Webster, Ethelyn McKinney, and Lena Weinstein to Ireland.[1]

During this period, Webster continued to write short stories and began adapting some of her books for the stage. In 1911, Just Patty was published, and Webster began writing the novel Daddy-Long-Legs while staying at an old farmhouse in Tyringham, Massachusetts. Webster's most famous work originally was published as a serial in the Ladies' Home Journal and tells the story of a girl named Jerusha Abbott, an orphan whose attendance at a women's college is sponsored by an anonymous benefactor. Apart from an introductory chapter, the novel takes the form of letters written by the newly styled Judy to her benefactor. It was published in October 1912 to popular and critical acclaim.[1]

Webster dramatized Daddy-Long-Legs during 1913, and in 1914 spent four months on tour with the play, which starred a young Ruth Chatterton as Judy. After tryouts in Atlantic City; Washington, D.C.; Syracuse, New York; Rochester, New York; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Chicago, the play opened at the Gaiety Theatre in New York City in September 1914 and ran until May 1915. It toured widely throughout the U.S. The book and play became a focus for efforts for charitable work and reform; "Daddy-Long-Legs" dolls were sold to raise money to fund the adoption of orphans into families.

Webster's success was overshadowed by the battle of her college friend, Adelaide Crapsey, with tuberculosis, leading to Crapsey's death in October 1914. In June 1915, Glenn Ford McKinney was granted a divorce, and he and Webster were married in a quiet ceremony in September in Washington, Connecticut. They honeymooned at McKinney's camp near Quebec City, Canada and were visited by former president Theodore Roosevelt,[5] who invited himself, saying: "I've always wanted to meet Jean Webster. We can put up a partition in the cabin."[1]

Returning to the U.S., the newlyweds shared Webster's apartment overlooking Central Park and McKinney's Tymor farm in Dutchess County, New York. In November 1915, Dear Enemy, a sequel to Daddy-Long-Legs, was published, and it was a bestseller too.[6] Also epistolary in form, it chronicles the adventures of a college friend of Judy's who becomes the superintendent of the orphanage in which Judy was raised.[1] Webster became pregnant and according to family tradition, was warned that her pregnancy might be dangerous. She suffered severely from morning sickness, but by February 1916 was feeling better and was able to return to her many activities: social events, prison visits, and meetings about orphanage reform and women's suffrage. She also began a book and play set in Sri Lanka. Her friends reported that they had never seen her happier.[1]

Death

[edit]Jean Webster entered the Sloan Hospital for Women, New York on the afternoon of June 10, 1916. Glenn McKinney, recalled from his 25th reunion at Princeton University, arrived 90 minutes before Webster gave birth, at 10:30 p.m, to a six-and-a-quarter-pound daughter. All was well initially, but Jean Webster became ill and died of childbirth fever at 7:30 am on June 11, 1916. Her daughter was named Jean (Little Jean) in her honor.[1]

Themes

[edit]Jean Webster was active political and socially, and often included issues of socio-political interest in her books.[6]

Eugenics and heredity

[edit]The eugenics movement was a hot topic when Jean Webster was writing her novels. In particular, Richard L. Dugdale's 1877 book about the Jukes family as well as Henry Goddard's 1912 study of the Kallikak family were widely read at the time. Webster's Dear Enemy mentions and summarizes the books approvingly, to some degree, although her protagonist, Sallie McBride, ultimately declares that she doesn't "believe that there's one thing in heredity," provided children are raised in a nurturing environment. Nevertheless, eugenics as an idea of 'scientific truth'— generally accepted by the intelligentsia of the time— does come through in the novel.

Institutional reform

[edit]From her college years, Webster was involved in reform movements, and was a member of the State Charities Aid Association, including visiting orphanages, fundraising for dependent children and arranging for adoptions. In Dear Enemy she names as a model the Pleasantville Cottage School, a cottage-based orphanage that Webster had visited.

Women's issues

[edit]Jean Webster supported women's suffrage and education for women. She participated in marches in support of votes for women, and having benefited from her education at Vassar, she remained actively involved with the college. Her novels also promoted the idea of education for women, and her major characters explicitly supported women's suffrage.[6]

When Patty Went to College

[edit]| Author | Jean Webster |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | The Century Company |

Publication date | 1903 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| OCLC | 2185725 |

When Patty Went to College is Jean Webster's first novel, published in 1903. It is a humorous look at life in a women's college at the turn of the 20th century. Patty Wyatt, the protagonist of this story is a bright, fun-loving, imperturbable young woman who does not like to conform. The book describes her many escapades on campus during her senior year at college. Patty enjoys life on campus and uses her energies in playing pranks and for the entertainment of herself and her friends. An intelligent young woman, she uses creative methods to study only as much as she feels necessary. Patty is, however, a believer in causes and a champion of the weak. She goes out of her way to help a homesick freshman, Olivia Copeland, who believes she will be sent home when she fails three subjects in the examination.

The end of the book sees Patty reflecting on what her life after college might be like. She plays hooky from chapel and meets a bishop. In a chat with the bishop, Patty realizes that being irresponsible and evasive at a young age could adversely affect her character as an adult and decides to try to be a more responsible person.

The novel was published in the U.K. by Hodder and Stoughton in 1915 as Patty & Priscilla.

Bibliography

[edit]- When Patty Went to College (1903)

- Wheat Princess (1905)

- Jerry Junior (1907)

- The Four Pools Mystery (1908)

- Much Ado About Peter (1909)

- Just Patty (1911)

- Daddy-Long-Legs (1912)

- Dear Enemy (1915)

Biography

[edit]- Boewe, Mary (2007). "Bewildered, Bothered, and Bewitched: Mark Twain's View of Three Women Writers". Mark Twain Journal. 45 (1): 17–24.

- Simpson, Alan; Simpson, Mary; Connor, Ralph (1984). Jean Webster: Storyteller. Poughkeepsie: Tymor Associates. Library of Congress Catalog Number 84–50869.

- [IT] Sara Staffolani, C'è sempre il sole dietro le nuvole. Vita e opere di Jean Webster, flower-ed 2018. ISBN ebook 978-88-85628-23-6 ISBN cartaceo 978-88-85628-24-3

- Sara Staffolani, Every Cloud Has Its Silver Lining. Life and Works of Jean Webster, flower-ed 2021. ISBN 978-88-85628-85-4

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Simpson, Alan; Simpson, Mary; Connor, Ralph (1984). Jean Webster: Storyteller. Poughkeepsie: Tymor Associates. Library of Congress Catalog Number 84–50869.

- ^ "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ "Read the eBook The valley of opportunity; year book, 1920. Binghamton, Endicott, Johnson City, Port Dickinson, Union .. by Binghamton (N.Y.). Chamber of Commerce online for free (page 13 of 19)". www.ebooksread.com. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c Jean, Webster (1940). Daddy-Long-Legs. New York, NY: Grosset and Dunlap. pp. "Introduction: Jean Webster" pages 11–19. ASIN: B000GQOF3G.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1916). A Book-Lover's Holidays in the Open. New York: Charles Scribner’s sons.

- ^ a b c Keely, Karen (September 2004). "Teaching Eugenics to Children:Heredity and Reform in Jean Webster's Daddy-Long-Legs and Dear Enemy". The Lion and the Unicorn. 28 (3): 363–389. doi:10.1353/uni.2004.0032. S2CID 143332948.

External links

[edit]Sources

- Works by Jean Webster at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Jean Webster on Overdrive

- Works by Alice Jane Chandler Webster at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Jean Webster at the Internet Archive

- Works by Jean Webster at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Other

- Alkalay-Gut, Karen (July 6, 2005). "Jean Webster". Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- "Jean Webster". Vassar Encyclopaedia. 2005. Archived from the original on March 24, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- Jean Webster in 1915(Univ. Washington/J.Willis Sayre collection)

Jean Webster

View on GrokipediaJean Webster (July 24, 1876 – June 11, 1916), born Alice Jane Chandler Webster, was an American author and social reformer whose novels often featured spirited young women navigating personal growth amid progressive ideals.[1][2]

Daughter of publisher Charles L. Webster, business partner to Mark Twain, she graduated from Vassar College in 1901 with studies in English and economics, experiences that informed her advocacy for women's suffrage, orphan care, and prison reform.[1][3]

Her breakthrough novel Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), an epistolary tale of an orphaned girl's college education funded by a mysterious patron, became a bestseller and was adapted for stage and screen, highlighting themes of education and social mobility that reflected her own visits to institutions for the disadvantaged.[1][3]

Webster produced eight novels, including the sequel Dear Enemy (1915), alongside plays and short stories, before marrying mining engineer Glenn Ford McKinney in 1915 and dying from childbirth complications at age 39, shortly after her daughter's birth.[1]

Early Life and Education

Childhood and Family Background

Alice Jane Chandler Webster was born on July 24, 1876, in Fredonia, New York, to Charles Luther Webster and Annie Moffett Webster, who had married the previous year.[4][5] She was the couple's firstborn child and grew up in an environment shaped by her mother's familial ties to literary prominence, as Annie Moffett was the niece of Samuel L. Clemens, known as Mark Twain.[1][2] Charles Webster, originally from Charlotte, New York, worked as Mark Twain's business manager before being appointed to lead the Charles L. Webster & Company publishing house, established in 1884 to handle Twain's works and others, including Ulysses S. Grant's memoirs.[3][4] This venture prompted the family's relocation from Fredonia to Manhattan that year, exposing young Webster to urban life amid her father's professional responsibilities.[6] The household reflected a matriarchal dynamic influenced by Annie Webster's activist inclinations, though financial strains emerged later when the firm declared bankruptcy in 1894, leading to Charles Webster's suicide in 1901.[2][6] Webster's early years were marked by these familial connections to publishing and literature, fostering her later interests, while the instability of her father's business underscored economic vulnerabilities in the household.[4] She later adopted the name Jean during attendance at a preparatory school, distancing somewhat from her given name amid these influences.[7]College Years at Vassar

Jean Webster entered Vassar College in 1897 at the age of 21, joining the class of 1901.[1] She majored in English while concentrating her studies in economics.[1] During her freshman year, Webster credited Vassar's writing course with teaching her essential skills in composition, which she later applied to her novel-writing career.[8] As an undergraduate, Webster actively contributed to campus literary life by writing stories for the Vassar Miscellany and editing and illustrating the Vassarion yearbook.[1] [9] She also penned a weekly column of "chatty news" for the Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier, honing her journalistic style outside the classroom.[9] Additionally, she produced plays and other creative works, often in collaboration with her roommate and close friend Adelaide Crapsey, a poet who shared her interest in innovative expression; the two even participated in a 1900 mock election on campus, voting for socialist Eugene V. Debs.[1] Webster's engagement extended to social reform efforts, including work with the College Settlement House, which was influenced by her enrollment in Dr. Herbert Mills's course on "Charities and Corrections."[1] She spent one semester studying abroad in France, Italy, and England, broadening her perspectives during her time at Vassar.[9] These experiences at the college, including its emphasis on personal development and experiential writing under faculty like Laura Johnson Wylie, directly informed the settings and themes of her early novels, such as When Patty Went to College (1903).[8] Webster graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1901.[1]Literary Career

Early Publications and Style Development

Webster's literary career commenced shortly after her 1901 graduation from Vassar College, when she relocated to New York City and secured freelance writing assignments with magazines such as McClure's and Ladies' Home Journal.[1] Her earliest outputs consisted of short stories depicting the escapades of college-aged women, which she serialized in periodicals before compiling them into her debut novel, When Patty Went to College, released by The Century Company on October 23, 1903.[10] The narrative centers on Patty Wyatt, a spirited freshman engaging in pranks and romantic pursuits at a prestigious women's college modeled after Vassar, employing a series of interconnected vignettes to highlight youthful rebellion against institutional conventions.[11] This initial work established Webster's signature style of light-hearted satire infused with sharp observational humor, emphasizing clever dialogue and the foibles of privileged young women without descending into overt didacticism.[12] Critics noted its resemblance to the comedic sketches of her granduncle Mark Twain, though Webster's tone remained gentler and more focused on female social dynamics than on broader American vernacular critique.[5] Building on this foundation, her subsequent early publications expanded the thematic range while retaining witty, character-driven narratives: The Wheat Princess (1905), a romantic tale of an American heiress entangled in Italian intrigue; Jerry Junior (1907), a farce involving mistaken identities during European travels; and The Four-Pools Mystery (1908), her sole venture into detective fiction, where a Southern estate's secrets unfold through amateur sleuthing.[13] These pre-1910 novels marked a stylistic evolution from confined campus humor to more adventurous, cosmopolitan settings, incorporating elements of romance and mild suspense to appeal to a growing audience for escapist women's fiction.[14] Webster's prose consistently prioritized brisk pacing and relatable protagonists—often independent, resourceful females challenging genteel expectations—foreshadowing the epistolary innovation of her later breakthrough, Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), while grounding her work in empirical sketches of early 20th-century gender roles derived from personal travels and observations.[13] By 1909, with Much Ado About Peter, she had refined a formula blending comedy with subtle advocacy for youthful autonomy, evidenced by sales figures that positioned her as an emerging voice in popular literature, with When Patty Went to College alone circulating over 10,000 copies within its first year.[5]Major Works and Commercial Success

Webster's literary output included several novels prior to her breakthrough, such as When Patty Went to College (1903), a collection of stories depicting campus life at a women's institution inspired by her Vassar years, and The Four-Pools Mystery (1908), her venture into detective fiction set in rural Kentucky.[2][15] Her most prominent work, Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), marked a turning point in commercial viability; serialized from April to September in Ladies' Home Journal under Curtis Publishing Company and released in book form by The Century Company that October, the epistolary tale of orphan Jerusha "Judy" Abbott's correspondence with her anonymous benefactor captivated readers with its blend of humor, romance, and social observation. The novel's stage adaptation premiered successfully at the Gaiety Theatre, featuring Ruth Chatterton and running to acclaim, extending its reach beyond print sales.[16][17] The sequel Dear Enemy (1915) sustained this momentum, shifting focus to Sallie McBride's letters detailing her management of the John Grier Home orphanage and her evolving relationship with a Scottish doctor; published by The Century Company, it built directly on the prior book's characters and themes, achieving notable readership in its era.[18][4]Playwriting and Other Formats

Webster adapted her 1912 novel Daddy-Long-Legs into a four-act comedic play of the same title, published in 1914 by Samuel French.[19] The stage version retained the epistolary elements of the original while emphasizing dramatic dialogue and character interactions, centering on the orphan Judy Abbott's correspondence with her anonymous benefactor, Jervis Pendleton.[19] This work marked her most prominent foray into playwriting, with the play credited to her as playwright for its 1914 production.[20] During her college years at Vassar and throughout her career, Webster composed numerous plays alongside her novels and short stories, though many remain unpublished or lesser-known.[1] These dramatic efforts reflected her interest in light comedy and social themes, similar to her prose style, but specific titles beyond Daddy Long-Legs are sparsely documented in available records. Webster's works extended to other formats through adaptations rather than original authorship in film or screenplays. Daddy-Long-Legs inspired multiple motion picture versions, including silent films in 1919 and subsequent releases in 1931 and 1955, broadening her reach beyond print and stage.[21] These cinematic interpretations amplified the commercial success of her narratives, though Webster herself predeceased most major adaptations, limiting her direct involvement.[21]Social Reform Advocacy

Institutional and Child Welfare Reform

Webster's engagement with institutional and child welfare reform began during her undergraduate studies at Vassar College, where she enrolled in courses on welfare and penal reform that involved firsthand visits to facilities for delinquent and destitute children.[4] These experiences profoundly influenced her, leading her to volunteer at the College Settlement House in New York City, an organization focused on aiding impoverished immigrants and urban poor through practical social services.[4] Her exposure to the systemic shortcomings of such institutions fostered a commitment to addressing the dehumanizing effects of rigid, factory-like care models prevalent in early 20th-century orphanages and reformatories. As an advocate, Webster championed reforms emphasizing individualized treatment over mass institutionalization for dependent children, drawing from Progressive Era critiques of overcrowded asylums that prioritized uniformity and discipline at the expense of child development.[1] She remained a lifelong supporter of orphanage reform, aligning with contemporaries who argued for foster care alternatives and improved sanitation, education, and emotional nurturing in state-run homes.[2] While not documented as holding formal committee positions on child welfare—unlike her involvement in prison reform panels—her advocacy manifested through public writing and influence on policy discourse.[3] Webster's novels served as vehicles for these ideas, with Daddy-Long-Legs (1912) depicting the stark, regimented life at the fictional John Grier Home orphanage, where protagonist Jerusha "Judy" Abbott endures rote labor and limited freedoms until sponsored for education.[22] The work highlighted empirical flaws in institutional dependency, such as stunted personal growth and lack of vocational training, contributing to public calls for systemic overhaul in U.S. child welfare practices around 1912. Its sequel, Dear Enemy (1915), explicitly dramatizes reform efforts as Sallie McBride assumes control of the same orphanage on March 15, 1914, implementing changes like nutritional improvements, play-based education, and selective placements for disabled children while decrying the "evils of institutional care" that bred uniformity and suppressed individuality.[18] Through epistolary narrative and satirical sketches, Webster critiqued causal links between poor institutional conditions—such as inadequate staffing ratios and punitive regimes—and long-term outcomes like illiteracy and maladjustment, urging a shift toward family-like environments backed by emerging social science data on child psychology.[18] These portrayals, grounded in her Vassar-informed observations, amplified reformist pressures on bodies like the New York State Board of Charities, though Webster prioritized narrative persuasion over direct lobbying.Women's Suffrage and Gender Roles

Jean Webster actively supported the women's suffrage movement, viewing the vote as essential to female empowerment during the Progressive Era. As a Vassar alumna, she aligned with contemporaries who pushed for political equality, integrating suffrage advocacy into her public life and writings amid campaigns that culminated in the Nineteenth Amendment's ratification in 1920.[1][2] Her fiction challenged conventional gender roles by depicting educated women achieving independence through intellectual pursuits and professional endeavors, rather than relying solely on marriage for security. In Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), protagonist Jerusha Abbott secures a college education and trains as a writer, embodying Webster's conviction that women's access to higher learning fostered self-reliance and critiqued dependency on male patronage. The narrative underscores economic autonomy, with Judy questioning societal norms that confined women to domesticity and advocating for their civic participation, including the vote.[23][24] Similarly, Dear Enemy (1915), a sequel narrated by Sallie McBride, portrays a woman reforming an orphanage through managerial initiative, highlighting female competence in reformist and administrative spheres typically reserved for men. Webster's protagonists thus model agency, prioritizing personal growth and social contribution over traditional femininity, a stance reflective of her broader critique of patriarchal constraints. Literary analysis posits these portrayals as subversive, promoting alternatives like career-oriented fulfillment to counter Victorian-era expectations of subservience.[23][1] Webster's advocacy extended to education as a cornerstone of gender equity, arguing it equipped women to navigate and reshape societal roles. Her emphasis on female voices in epistolary formats amplified these themes, fostering reader identification with characters who defied limitations on women's public engagement.[24][23]Engagement with Eugenics and Heredity

In her 1915 novel Dear Enemy, the sequel to Daddy-Long-Legs, Jean Webster explored the interplay between heredity and environment amid orphanage reform efforts, reflecting progressive-era debates on human improvement. The protagonist, Sallie McBride, initially prioritizes nurture, asserting in a letter that "Privately, I don't believe there's one thing in heredity, provided you snatch the babies away" from adverse conditions early enough, suggesting environment could override genetic inheritance.[18] However, through managing the John Grier Home, Sallie confronts cases where poor parental backgrounds—such as alcoholism or criminality—manifest in children's intractable behaviors despite interventions, leading her to advocate tracing family histories for placement decisions and emphasizing "good stock" for successful adoptions.[25] This narrative arc underscores a Lamarckian-inflected eugenics, where acquired traits influence offspring but inherent heredity sets limits on reform, aligning with contemporaneous views that social progress demanded selective breeding alongside environmental uplift.[25] Webster's portrayal promotes positive eugenics—encouraging unions and child-rearing among the fit—over coercive measures, as Sallie implements "eugenic protocols" like matching children to families based on ancestral health and intellect, while rejecting unfit pairings.[26] Literary scholar Karen A. Keely interprets this as didactic intent, arguing Webster used accessible epistolary fiction to educate young readers on heredity's primacy in reform, countering naive environmentalism by showing that "institutional change alone cannot overcome bad heredity."[27] In Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), the theme emerges less explicitly, with orphan Judy Abbott's elevation through education implying innate potential amplified by opportunity, yet Webster hints at hereditary advantages in her references to class-bound traits and family legacies.[27] Webster's moderate stance mirrored elite reformers' consensus in the 1910s, where eugenics informed welfare policies without endorsing extremes like sterilization; she viewed heredity as probabilistic, malleable by early intervention but foundational to outcomes.[28] No records indicate formal affiliation with eugenics organizations, but her advocacy for tracing orphans' pedigrees and prioritizing "desirable" adoptions integrated scientific racism-lite ideas prevalent in academia and social work, prioritizing empirical lineage data over sentiment.[25] This engagement critiqued unchecked pauper breeding while affirming nurture's role for hereditarily sound children, blending optimism with genetic determinism.Personal Life

Relationships and Marriage

Jean Webster maintained a long-term romantic relationship with Glenn Ford McKinney, a New York lawyer and son of John Luke McKinney, a co-founder of Standard Oil.[1] [4] Their involvement began around 1907, when McKinney was still married to his first wife, who suffered from severe mental illness, leading to a secret engagement that lasted approximately seven years.[14] [29] McKinney secured a divorce in June 1915, after which Webster and McKinney married in a private ceremony on September 7, 1915, in Washington, Connecticut.[17] The couple resided primarily in New York City, with additional time spent at a home in the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts.[30] Their marriage produced one child, a daughter named Jean Webster McKinney, born on June 10, 1916.[30] No other significant romantic relationships are documented in Webster's life prior to or outside this partnership.[1]Health and Death

Webster experienced no documented chronic health conditions prior to her pregnancy in 1916, though the era's limited medical interventions for postpartum infections contributed to high maternal mortality rates.[1] On June 10, 1916, she entered Sloane Hospital for Women in New York City to deliver her first child, a daughter named Jean Webster McKinney.[2] The birth initially appeared successful, but Webster developed puerperal fever—a bacterial infection common in postpartum settings before widespread antibiotic use and aseptic techniques.[6] She died from these complications the next morning, June 11, 1916, at 7:30 a.m., at age 39.[30] Her daughter survived infancy under the care of family, including Webster's widower, Glenn Ford McKinney.[31]Legacy and Reception

Adaptations and Cultural Impact

Webster's novel Daddy-Long-Legs (1912) was adapted into a stage play of the same name by the author herself, which premiered on Broadway on September 28, 1914.[32] The play contributed to the novel's commercial success and helped establish its themes of orphanage reform and female independence in live theater.[32] Film adaptations include the 1931 version directed by Alfred Santell, starring Miriam Hopkins and Warner Baxter, which closely followed the novel's epistolary structure and orphan protagonist narrative.[33] A looser interpretation appeared in 1935's Curly Top, featuring Shirley Temple as an orphaned girl under a benefactor's care, emphasizing sentimental elements over Webster's social critique.[33] The 1955 musical film Daddy Long Legs, directed by Jean Negulesco and starring Leslie Caron and Fred Astaire, relocated the story to France and incorporated original songs by Johnny Mercer and Harry Warren, grossing over $7 million at the box office and introducing the work to mid-century audiences.[32] In theater, a 1952 British musical comedy titled Love from Judy drew from the novel, adapting its romance and mystery for stage audiences.[24] A more faithful two-person musical adaptation, with book by John Caird and music and lyrics by Paul Gordon, premiered in 2009 and has been staged internationally, including at venues like the Ocala Civic Theatre in 2025 and Broadway Rose Theatre Company, highlighting the story's intimate epistolary format and themes of wit and tenacity.[34] [35] The sequel Dear Enemy (1915) received a 1981 British television adaptation starring Vanessa Knox-Mawer and Patrick Malahide, focusing on orphanage reform efforts.[21] Culturally, Daddy-Long-Legs has endured as a touchstone for young adult literature, influencing depictions of self-reliant female protagonists and critiques of institutional welfare systems, with its 1912 publication directly challenging early 20th-century orphanage conditions through empirical observations of underfunded asylums.[1] The novel's adaptations across media have sustained its legacy, promoting discussions on education access and social mobility, as evidenced by its repeated theatrical revivals and scholarly analyses of its reformist undertones.[36] Webster's emphasis on personal agency amid heredity and environment debates has informed broader literary engagements with progressive era social issues, though her works' optimistic resolutions sometimes tempered radical calls for systemic change.[24]Critical Assessments and Controversies

Webster's novels, particularly Daddy-Long-Legs (1912) and its sequel Dear Enemy (1915), received widespread acclaim upon publication for their witty epistolary style, spirited protagonists, and advocacy for social reforms such as orphanage improvement and women's education, with contemporary reviewers like those in The New York Times praising the "delightful sense of humor" and charm that made them instant bestsellers.[37] However, later scholarship has highlighted limitations in her portrayals, noting that while subversive of Victorian patriarchy through independent female leads, the narratives often reinforce class hierarchies and paternalistic solutions to poverty, as seen in the benefactor's anonymous control over the heroine's life in Daddy-Long-Legs.[1] A primary controversy surrounds Webster's incorporation of eugenic principles, which grew more explicit in her later works amid the Progressive Era's embrace of hereditarian science by reformers. In Dear Enemy, protagonist Sallie McNicoll transforms an orphanage by emphasizing "improving the stock" through selective pairings and environmental reforms informed by inheritance theories, reflecting Webster's increasing conviction in eugenics as a tool for societal uplift, as evidenced by her evolving narrative focus on heredity over pure nurture.[28] This alignment with early 20th-century eugenics—promoted by figures like Charles Davenport—has drawn modern criticism for implicitly endorsing ideas later discredited and linked to coercive policies, though Webster framed them as benevolent child welfare rather than racial exclusion.[28] Critics have also faulted the romantic elements in Daddy-Long-Legs for problematic power imbalances, where the older, wealthy trustee's secret identity as the heroine's suitor creates a dynamic of deception and dependency, with the protagonist's swift forgiveness of the ruse underscoring dated gender norms despite feminist undertones.[38] Such assessments, drawn from narrative analyses, argue that while empowering in educational themes, the plots inadvertently model unequal relationships, contributing to retrospective views of her oeuvre as blending progressive ideals with era-typical biases in class and heredity.[39]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/When_Patty_Went_to_College