Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

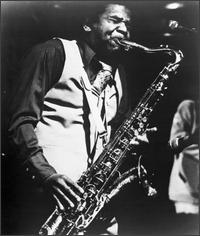

Junior Walker

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr. (June 14, 1931 – November 23, 1995), known professionally as Junior Walker, was an American multi-instrumentalist (primarily saxophonist) and vocalist who recorded for Motown during the 1960s. He also performed as a session and live-performing saxophonist with the band Foreigner during the 1980s.[1]

Early life

[edit]This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (June 2025) |

Walker was born Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr. on June 14, 1931, in Blytheville, Arkansas, but grew up in South Bend, Indiana. He began playing saxophone while in high school, and his saxophone style was the anchor for the sound of the bands he later played in.

Career

[edit]His career started when he developed his own band in the mid-1950s as the Jumping Jacks.[1] His longtime friend and drummer Billy Nicks (1935–2017) formed his own group, the Rhythm Rockers. Periodically, Nicks would sit in on Jumping Jack's shows, and Walker would sit in on the Rhythm Rockers shows.

Nicks obtained a permanent gig at a local TV station in South Bend, Indiana, and asked Walker to join him and keyboard player Fred Patton permanently. Nicks asked Willie Woods (1936–1997), a local singer, to perform with the group; Woods would learn how to play guitar. When Nicks was drafted into the United States Army, Walker convinced the band to move from South Bend to Battle Creek, Michigan.[1] While performing in Benton Harbor, Walker found a drummer, Tony Washington, to replace Nicks.[1] Eventually, Fred Patton left the group, and Victor Thomas stepped in.[1] The original name, The Rhythm Rockers, was changed to "The All Stars." Walker's style was inspired by jump blues and early R&B, particularly players like Louis Jordan, Earl Bostic, and Illinois Jacquet.[1]

The group was spotted by Johnny Bristol, and in 1961 he recommended them to Harvey Fuqua, who had his own record labels.[1] Once the group started recording on the Harvey label, their name was changed to Jr. Walker & the All Stars. The name was modified again when Fuqua's labels were taken over by Motown's Berry Gordy, and Jr. Walker & the All Stars became members of the Motown family, recording for their Soul imprint in 1964.[1]

The members of the band changed after the acquisition of the Harvey label. Tony Washington, the drummer, quit the group, and James Graves joined. Their first and signature hit was "Shotgun",[2] written and composed by Walker and produced by Berry Gordy, which featured the Funk Brothers' James Jamerson on bass and Benny Benjamin on drums. "Shotgun" reached No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 1 on the R&B chart in 1965, and was followed by many other hits, such as "(I'm a) Road Runner", "Shake and Fingerpop" and remakes of two Motown songs "Come See About Me" and "How Sweet It Is (to Be Loved by You)", that had previously been hits for the Supremes and Marvin Gaye respectively.[2] In 1966, Graves left and was replaced by old cohort Billy "Stix" Nicks, and Walker's hits continued apace with tunes such as "I'm a Road Runner" and "Pucker Up Buttercup".[1]

In 1969, the group had another hit enter the top 5, "What Does It Take (to Win Your Love)".[2][1] A Motown quality control meeting rejected this song for single release, but radio station DJs made the track popular, resulting in Motown releasing it as a single, whereupon it reached No. 4 on the Hot 100 and No. 1 on the R&B chart. From that time on, Walker sang more on the records than earlier in their career.[2] He landed several more R&B Top Ten hits over the next few years, with the last coming in 1972.[1] He toured the UK in 1970 with drummer Jerome Teasley (Wilson Pickett), guitarist Phil Wright (brother of Betty "Clean Up Woman" Wright), keyboardist Sonny Holley (The Temptations) and the youthful Liverpool UK bassist Norm Bellis (Apple). The band played two venues on each of the 14 nights. The finale was at The Valbonne in London's West End. They were joined on stage by The Four Tops for an impromptu set. In 1979, Walker went solo, disbanding the All Stars, and was signed to Norman Whitfield's Whitfield Records label,[1] but he was not as successful on his own as he had been with the All Stars in his Motown period.

Walker re-formed the All Stars in the 1980s. On April 11, 1981, Walker was the musical guest on the season finale of Saturday Night Live. Foreigner's 1981 album 4 featured Walker's sax solo on "Urgent".[2] He later recorded his own version of the song for the 1983 All Stars's album Blow the House Down.[3] Walker's version was also featured in the 1985 Madonna film Desperately Seeking Susan. In 1983, Walker was re-signed with Motown.[1] In the same year, he appeared as a part of the Motown 25 television special which aired on May 16, 1983.

In 1988, Walker played opposite Sam Moore as one-half of the fictional soul duo The Swanky Modes in the comedy Tapeheads. Several songs were recorded for the soundtrack, including "Bet Your Bottom Dollar" and "Ordinary Man", produced by ex-Blondie member Nigel Harrison.

Death

[edit]Walker died of cancer at the age of 64 in Battle Creek, Michigan, on November 23, 1995.[1] He is buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Battle Creek under a marker inscribed with both his birth name of Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr. and his stage name.

Awards and honors

[edit]Junior Walker & the All Stars received three Grammy Award nominations:[4]

- "Shotgun" - Best Rhythm and Blues Recording (1965)

- "What Does It Take" - Best R&B Instrumental Performance (1969)

- "Wishing on a Star" - Best R&B Instrumental Performance (1979)

He was inducted into the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1995. Walker's "Shotgun" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2002. Jr. Walker & the All Stars were voted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2007.[5]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]| Year | Album | Chart positions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [6] |

US R&B [6] | ||||

| 1965 | Shotgun

|

108 | 1 | ||

| 1966 | Soul Session

|

130 | 7 | ||

Road Runner

|

64 | 6 | |||

| 1969 | Home Cookin'

|

172 | 26 | ||

Gotta Hold on to This Feeling

|

92 | 12 | |||

| 1970 | A Gassssssssss!

|

110 | 28 | ||

| 1971 | Rainbow Funk

|

91 | 12 | ||

Moody Jr.

|

142 | 22 | |||

| 1973 | Peace and Understanding Is Hard to Find

|

— | 47 | ||

| 1974 | Jr. Walker & the All Stars

|

— | — | ||

| 1976 | Hot Shot

|

— | 45 | ||

Sax Appeal

|

— | — | |||

| 1977 | Whopper Bopper Show Stopper

|

— | — | ||

| 1978 | Smooth

|

— | — | ||

| 1979 | Back Street Boogie

|

— | 72 | ||

| 1983 | Blow the House Down

|

— | — | ||

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory. | |||||

Live albums

[edit]| Year | Album | Chart positions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [6] |

US R&B [6] | ||||

| 1967 | "Live!"

|

119 | 22 | ||

| 1970 | Live

|

— | 22 | ||

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart. | |||||

Compilation albums

[edit]| Year | Album | Chart positions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [6] |

US R&B [6] | ||||

| 1969 | Greatest Hits

|

43 | 19 | ||

| 1973 | Greatest Hits, Vol. 2 (UK-only)

|

— | — | ||

| 1974 | Anthology

|

— | — | ||

| 1982 | Greatest Hits (UK-only)

|

— | — | ||

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart. | |||||

Singles

[edit]| Year | Title (A-side / B-side) (Both sides from same album except where indicated) |

Peak chart positions | Album | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US [6] |

US R&B [6] |

UK [7] | ||||

| 1962 | "Twist Lackawanna" b/w "Willie's Blues" (Non-album track) |

— | — | — | Road Runner | |

| "Cleo's Mood" b/w "Brainwasher" (from Soul Session) |

— | — | — | Shotgun | ||

| 1963 | "Good Rockin'" b/w "Brainwasher Pt. 2" (Non-album track) |

— | — | — | Soul Session | |

| 1964 | "Satan's Blues" b/w "Monkey Jump" (from Shotgun) |

— | — | — | ||

| 1965 | "Shotgun" b/w "Hot Cha" |

4 | 1 | — | Shotgun | |

| "Do the Boomerang" b/w "Tune Up" |

36 | 10 | — | |||

| "Shake and Fingerpop"[8] / | 29 | 7 | — | |||

| "Cleo's Back" | 43 | 7 | — | |||

| 1966 | "(I'm a) Road Runner" b/w "Shoot Your Shot" |

20 | 4 | 12 | ||

| "Cleo's Mood" b/w "Baby You Know You Ain't Right" (from Road Runner) |

50 | 14 | — | |||

| "How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You)" b/w "Nothing But Soul" |

18 | 3 | 22 | Road Runner | ||

| "Money (That's What I Want), Pt.1" b/w "Money (That's What I Want), Pt. 2" |

52 | 35 | — | |||

| 1967 | "Pucker Up Buttercup" b/w "Anyway You Wanta" |

31 | 11 | — | ||

| "Shoot Your Shot" b/w "Ain't That the Truth" |

44 | 33 | — | Shotgun | ||

| "Come See About Me" b/w "Sweet Soul" |

24 | 8 | — | Home Cookin' | ||

| 1968 | "Hip City, Pt. 2" b/w "Hip City, Pt. 1" |

31 | 7 | — | ||

| "Home Cookin'" b/w "Mutiny" |

42 | 19 | — | |||

| 1969 | "What Does It Take (to Win Your Love)" b/w "Brainwasher (Part 1)" (from Soul Session) |

4 | 1 | 13 | ||

| "These Eyes" b/w "I've Got to Find a Way to Win Maria Back" |

16 | 3 | — | What Does It Take to Win Your Love | ||

| 1970 | "Gotta Hold On to This Feeling" b/w "Clinging to the Thought That She's Coming Back" |

21 | 2 | — | ||

| "Do You See My Love (For You Growing)" b/w "Groove and Move" |

32 | 3 | — | A Gasssss | ||

| "Holly Holy" / | 75 | 33 | — | |||

| "Carry Your Own Load" | 117 | 50 | — | |||

| 1971 | "Take Me Girl, I'm Ready" b/w "Right On Brothers and Sisters" |

50 | 18 | 16 | Rainbow Funk | |

| "Way Back Home" b/w "Way Back Home" (Instrumental) |

52 | 24 | 35 | |||

| 1972 | "Walk in the Night" b/w "I Don't Want to Do Wrong" |

46 | 10 | 16 | Moody Jr. | |

| "Groove Thang" b/w "Me and My Family" |

— | — | — | |||

| 1973 | "Gimme That Beat (Part 1)" b/w "Gimme That Beat (Part 2)" |

101 | 50 | — | Peace & Understanding Is Hard to Find | |

| "I Don't Need No Reason" b/w "Country Boy" |

— | — | — | |||

| "Peace and Understanding (Is Hard to Find)" b/w "Soul Clappin'" |

— | — | — | |||

| 1974 | "Dancin' Like They Do on Soul Train" b/w "I Ain't That Easy to Lose" |

— | — | — | Jr. Walker & the All Stars | |

| 1976 | "I'm So Glad" b/w "Soul Clappin'" (from Peace & Understanding Is Hard to Find) |

— | — | — | Hot Shot | |

| "You Ain't No Ordinary Woman" b/w "Hot Shot" |

— | — | — | |||

| 1977 | "Hard Love" b/w "Whopper Bopper Show Stopper" (from Whopper Bopper Show Stopper) |

— | — | — | Smooth | |

| 1979 | "Wishing on a Star" b/w "Back Street Boogie" |

— | 89 | — | Back Street Boogie | |

| "Back Street Boogie" b/w "Don't Let Me Go Astray" |

— | — | — | |||

| 1983 | "Blow the House Down" b/w "Ball Baby" |

— | — | — | Blow the House Down | |

| "—" denotes releases that did not chart or were not released in that territory. | ||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Huey, Steve. "Junior Walker". AllMusic. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Colin Larkin, ed. (1993). The Guinness Who's Who of Soul Music (First ed.). Guinness Publishing. p. 285. ISBN 0-85112-733-9.

- ^ Hamilton, Andrew. "Junior Walker & the All-Stars: Blow the House Down". AllMusic. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ "Junior Walker And The All Stars". Grammy Awards. November 23, 2020.

- ^ "Michigan Rock and Roll Legends". www.michiganrockandrolllegends.com. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Charts & Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 590. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 26 – The Soul Reformation: Phase two, the Motown story. [Part 5]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 7.

External links

[edit]Junior Walker

View on GrokipediaEarly years

Childhood and family background

Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr., who would later be known professionally as Junior Walker, was born on June 14, 1931, in Blytheville, Arkansas.[1] His biological father was Autry DeWalt, and following family changes, including the involvement of his stepfather Roosevelt Walker, he adopted the surname Walker and the nickname "Junior," which originated from his stepfather.[1] His mother was Maria, who was 15 at his birth and later moved to South Bend, Indiana, for work. He was raised by his aunt and uncle, Plez and Verna DeWalt, from around age 3 or 4 for about 13 years.[1] These early family dynamics shaped his personal identity amid a period of transition in the American South during the Great Depression era.[8] At the age of five, Mixon's family relocated from Blytheville to South Bend, Indiana, seeking better opportunities amid economic hardships and rural limitations in Arkansas.[9] The move to the industrial hub of South Bend exposed him to a more urban environment, with its diverse working-class communities and manufacturing economy, which contrasted sharply with his rural birthplace and influenced his formative years.[1] This relocation, driven by family circumstances including the pursuit of stability, placed young Junior in a setting ripe for personal growth.[10] During his adolescence in South Bend, these early experiences laid the groundwork for his emerging interests.Musical influences and beginnings

Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr., known as Junior Walker, grew up in a Midwestern environment after his family relocated from Blytheville, Arkansas, to South Bend, Indiana, when he was five years old, immersing him in the local rhythm and blues scene.[3] At around age 16, Walker was inspired by the energetic jump blues and jive music of Louis Jordan, which prompted him to purchase a tenor saxophone and teach himself to play without formal instruction.[3][1] This self-taught approach allowed him to emulate the honking, expressive style of Jordan and other influences like Earl Bostic and Illinois Jacquet, laying the foundation for his raw, emotive sound.[1] During his high school years in South Bend, Walker honed his skills by forming amateur bands and performing tenor saxophone in the burgeoning local R&B circuit.[11] He assembled his first group, the Jumping Jacks, an instrumental ensemble featuring guitarist Willie Woods, organist Victor Thomas, and drummer Tony Washington, with whom he played at school events and community gatherings.[3][11] These experiences exposed him to the demands of live performance, where he began experimenting with a raspy, shout-like vocal delivery alongside his saxophone leads, blending the two to create a distinctive, audience-engaging presence.[6] Walker's early gigs with the Jumping Jacks included dances, teen proms, and small clubs around South Bend, where the band built a solid local reputation through energetic sets without venturing into professional recordings.[11][12] This amateur phase solidified his role as a bandleader and performer, emphasizing infectious rhythms and improvisational flair that would later define his career, all while remaining rooted in the unpolished energy of regional R&B.[3]Career

Pre-Motown and band formation

In the mid-1950s, Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr., who adopted the stage name Junior Walker from his stepfather, formed an instrumental group in South Bend, Indiana, initially called the Jumping Jacks, alongside guitarist Willie Woods; the band later relocated to Battle Creek, Michigan, where they added organist Victor Thomas and drummer James Graves, renaming themselves Jr. Walker & the All Stars around 1958.[13][1] Self-taught on the saxophone during his high school years in South Bend, Walker brought a raw, blues-inflected energy to the group's sound, drawing from jump blues and R&B influences.[1] The All Stars gained local notice playing clubs and events in the Midwest, where their high-energy performances blending R&B grooves and soulful instrumentals helped build a dedicated regional following.[6] In 1961, producer Johnny Bristol recommended the band to Harvey Fuqua, who signed them to his newly launched Harvey Records imprint (affiliated with Tri-Phi); this marked their entry into professional recording.[14] Over the next two years, they released three singles on the label, including the upbeat instrumental "Twist Lackawanna" backed with "Willie's Blues" in 1962, showcasing Walker's gritty saxophone leads and the band's tight rhythm section. These efforts, though not commercial hits, highlighted their raw, dance-oriented style amid the growing soul scene.[15] By 1963, financial pressures led Fuqua to fold Tri-Phi and Harvey into Motown Records, transitioning the All Stars into the larger Motown fold as one of the acquired acts; initially, they contributed as backing musicians while preparing their own material.[2] This pre-Motown period solidified the band's chemistry through relentless Midwest gigs, positioning them for broader exposure.[12]Motown breakthrough and hits

Junior Walker and the All Stars signed with Motown's Soul label in 1964, following earlier independent recordings, marking their entry into the label's roster after initial session contributions in Detroit's music scene.[16] Their debut Motown release came that year with the instrumental single "Monkey Jump" backed with "Satan's Blues," showcasing Walker's raw saxophone leads over tight R&B grooves, though it failed to chart significantly.[17] The group's breakthrough arrived in 1965 with "Shotgun," a high-energy track written by Walker himself under his birth name Autry DeWalt, produced by Berry Gordy and featuring gritty tenor sax riffs and Walker's raspy, shouted vocals that captured the raw excitement of a dance-floor frenzy.[18] The song propelled to No. 1 on the Billboard R&B chart and No. 4 on the Hot 100, establishing their signature blend of R&B, soul, and rock-infused upbeat rhythms that contrasted Motown's smoother vocal groups.[19] This hit was supported by the Funk Brothers, Motown's renowned house band, adding driving bass and drums that amplified its infectious, party-ready appeal.[20] Building on this momentum, the band delivered a string of Motown hits through the late 1960s, including "Do the Boomerang" in 1965 (No. 10 R&B), the instrumental "Shake and Fingerpop" later that year (No. 7 R&B, No. 29 Pop), and " (I'm a) Road Runner" in 1966 (No. 4 R&B, No. 20 Pop).[19] They also scored with covers like Marvin Gaye's "How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved by You)" (No. 18 R&B in 1966), Barrett Strong's "Money (That's What I Want)" released as a single in 1966, and the Supremes' "Come See About Me" (No. 8 R&B in 1967), adapting these Motown staples with Walker's distinctive sax-heavy, energetic reinterpretations.[21] Further successes included "Pucker Up Buttercup" in 1967 (No. 11 R&B) and "Gotta Hold On to This Feeling" in 1970 (No. 2 R&B, No. 21 Pop), the latter co-written by producers Frank Wilson and Jeffrey Bowen to highlight Walker's soulful pleas amid funky grooves.[19][22] Walker's gritty tenor saxophone solos, combined with his gravelly vocals and the band's driving rhythm section, defined their contributions to Motown's sound, bridging instrumental R&B with vocal soul in dance-oriented tracks that emphasized live-wire performance energy.[20] Collaborations with key Motown figures, including Gordy on production and songwriters like Strong for covers, helped craft this style, while their pre-Motown rawness provided a foundation for these polished yet visceral recordings. The group toured extensively as part of the Motown Revue, sharing stages with acts like the Supremes and the Temptations, which amplified their visibility and honed their high-octane live shows during the label's golden era.[23]Post-Motown developments

As their chart success waned in the mid-1970s, Jr. Walker & the All Stars released several Motown albums, including A Gasssss (1971) and Rainbow Funk (1971), but none achieved significant commercial impact. In 1979, the group departed Motown and signed with Norman Whitfield's Whitfield Records, issuing the album Back Street Boogie that year, which included singles like "Lover" but failed to chart.[12][24] Walker then focused on session work, providing a notable saxophone solo on Foreigner's "Urgent" in 1981, contributing to its peak at No. 4 on the Billboard Hot 100.[5] In 1983, he re-signed as a solo artist with Motown, releasing the album Blow the House Down, featuring the funky title track as a single aimed at contemporary audiences. Throughout the 1980s, Walker continued touring with versions of the All Stars, often performing alongside Motown contemporaries like the Four Tops, maintaining his reputation for energetic live shows until health issues limited his activity in the early 1990s.[2]Later life and death

Health challenges

In 1993, Walker was diagnosed with kidney cancer,[25] which prompted immediate medical treatments including surgery and ongoing care, significantly limiting his ability to tour and perform as vigorously as in previous decades.[26] The diagnosis marked a turning point, forcing him to scale back professional commitments in the 1990s to prioritize recovery, though he occasionally appeared on stage with reduced energy.[25] The cancer battle deeply affected Walker's family life, with his wife and their 11 children offering unwavering emotional and practical support during treatments and recovery periods at their home in Battle Creek, Michigan.[27] His son Autry DeWalt III—who had drummed for him on tours in the 1980s and early 1990s—provided hands-on assistance, helping manage household needs and accompanying him to medical appointments, strengthening family bonds amid the adversity.[28]Death and immediate aftermath

Junior Walker died on November 23, 1995, at the age of 64 in Battle Creek, Michigan, from complications related to cancer.[29][27] He had been battling the illness since a diagnosis in 1993, which progressively affected his mobility and led to his retirement from performing.[8] Funeral services for Walker were held in Battle Creek, with burial at Oak Hill Cemetery, where he is interred under a marker bearing both his birth name, Autry DeWalt Mixon Jr., and stage name, inscribed as "Junior (Shot Gun) Walker."[29][30] Immediate media tributes emphasized Walker's instrumental contributions to Motown's signature sound, portraying him as a premier saxophonist whose raw, energetic style influenced generations of musicians.[31][32] Guitarist Jimmy Vivino, who had recently shared a stage with Walker, remarked, "There isn't a sax player out there who didn't get something from him," underscoring the immediate recognition of his impact within the music community.[27] Walker was survived by his wife and 11 children, including son Autry DeWalt III, who had performed on drums with the All Stars in the 1990s.[27]Legacy and recognition

Musical influence

Junior Walker's sax-driven energy and raw R&B style significantly influenced subsequent rock and soul artists, particularly through his emphasis on gritty, instrumental hooks that bridged blues traditions with Motown's polished sound. Clarence Clemons, saxophonist for Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band, cited Walker alongside King Curtis as a key early influence, shaping Clemons' powerful, emotive playing that became integral to Springsteen's live performances and anthemic rock.[33][15] Walker's approach also resonated in rock circles, as seen in his guest saxophone on Foreigner's 1981 hit "Urgent," where his distinctive wail added soulful grit to the track's hard-rock edge, helping it reach the Top Five on the Billboard Hot 100.[34] His influence extended to jazz and fusion saxophonists like David Sanborn, who drew from Walker's energetic tenor style in developing his own smooth, blues-infused sound.[15] Walker's role in Motown's crossover success exemplified his ability to merge R&B with pop and rock elements, pioneering a "shout-soul" style characterized by exuberant call-and-response vocals and driving rhythms. Tracks like "Shotgun" (1965) achieved simultaneous No. 1 status on the R&B charts and No. 4 on the pop charts, demonstrating how Walker's blues-infused energy expanded Motown's appeal beyond traditional soul audiences.[15] This hybrid vigor later impacted horn-driven funk acts, with Tower of Power incorporating similar shout-soul dynamics; their 1972 track "Cleo's Back" directly sampled Walker's "Shoot Your Shot" (1967), echoing his rhythmic intensity and vocal exhortations in their own brass-heavy grooves. Walker's contributions extended to dance music and enduring party anthems, with "Shotgun"—inspired by a lively club dance craze—becoming a staple for its infectious, uptempo groove that encouraged communal movement. The song's legacy persists in popular culture, appearing in films and television such as For All Mankind (2019) and JoJo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling (1986), as well as commercials evoking 1960s nostalgia, underscoring its timeless role in soundtrack-driven entertainment.[35] Covers by artists like Vanilla Fudge (1969, reaching No. 68 on the Hot 100) and Billy Preston further amplified its influence, adapting the raw funk to psychedelic and gospel-soul contexts.[18] Within Motown, Walker provided informal guidance to emerging musicians through his band's raw, unpolished approach, which contrasted with the label's smoother productions and helped instill a sense of blues-rooted authenticity among younger acts navigating the studio environment. His ties to regional blues revival scenes stemmed from his early inspiration by jump blues pioneers like Louis Jordan and Earl Bostic, infusing Motown output with a down-home R&B counterpoint that preserved pre-rock energy amid the label's commercial evolution.[3] The Junior Walker & the All Stars' live performance legacy lies in their preservation of visceral R&B vitality, drawing packed venues like Battle Creek's El Grotto with high-energy sets that prioritized improvisation and audience interaction over scripted polish. This unfiltered intensity, captured in recordings like their 1970 live album, influenced later jam-oriented bands by demonstrating how soul could sustain extended, communal grooves rooted in blues traditions.[15]Awards and honors

Junior Walker & the All Stars received three Grammy Award nominations during their career, though they did not win any. Their 1965 hit "Shotgun" was nominated for Best Rhythm & Blues Recording at the 8th Annual Grammy Awards.[36] In 1969, "What Does It Take (To Win Your Love)" earned a nomination for Best R&B Instrumental Performance at the 11th Annual Grammy Awards.[37] Their final nomination came in 1980 for "Wishing on a Star" in the Best R&B Instrumental Performance category at the 22nd Annual Grammy Awards.[38] In 2002, "Shotgun" was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, recognizing its enduring historical and artistic significance.[16] Posthumously, Jr. Walker & the All Stars were inducted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame in 2007, celebrating their impact on the state's musical heritage.[12] Additionally, "Shotgun" was designated a Legendary Michigan Song in 2010 by the same organization.[12]Discography

Studio and live albums

Junior Walker & the All Stars released a series of studio albums during their Motown tenure, primarily on the Soul and Soul-Town imprints, emphasizing their signature blend of soul, R&B, and saxophone-driven instrumentals produced by Motown's in-house team including Berry Gordy and the Holland-Dozier-Holland collective.[2] These recordings captured the band's raw, energetic style, often built around Walker's gritty tenor sax and vocals, with production focusing on tight rhythm sections and horn arrangements to drive danceable tracks.[39] After departing Motown in 1979, Walker pursued independent releases, though output was more limited.[20] Key studio albums included their breakthrough Shotgun (1965, Soul), which featured the chart-topping title single and peaked at No. 1 on the Billboard R&B albums chart, establishing the band's commercial viability. Follow-up Soul Session (1966, Soul) reached No. 130 on the Billboard 200, showcasing covers and originals with a focus on instrumental jams. Road Runner (1966, Soul) conveyed a semi-live energy through crowd-like effects and peaked at No. 6 on the R&B chart, highlighting the band's road-tested sound. Later Motown efforts like Home Cookin' (1969, Soul) hit No. 26 on the R&B chart, incorporating funkier grooves amid the label's evolving production style. A Gasssss! (1969, Soul) continued this trajectory with psychedelic soul influences, while Moody (1971, Soul) explored more introspective tracks.[20] Live albums were fewer, with Road Runner (1966) incorporating simulated audience ambiance for a concert-like vibe, though not a true live recording. The band's primary live release, Jr. Walker & The All Stars "Live!" (1967, Soul), captured performances emphasizing extended sax solos and crowd interaction, but saw limited distribution. Post-Motown live efforts were minimal, with no major U.S. releases. A Greatest Hits Live collection appeared in niche formats during the 1980s, primarily for promotional or regional use.[40] In the digital era, Hip-O Select (a Motown/Universal imprint) issued expanded reissues, such as the 2019 box set Walk in the Night: The Motown '70s Studio Albums, remastering lesser-known titles like A Gasssss! (1969) and Moody (1971) with bonus tracks and liner notes on the band's transition to funk-soul.[41] These efforts made previously out-of-print material accessible via streaming and CD, preserving Walker's Motown catalog.[42]| Album Title | Year | Label | Peak R&B Chart Position (Billboard) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shotgun | 1965 | Soul | 1 |

| Soul Session | 1966 | Soul | - |

| Road Runner | 1966 | Soul | 6 |

| Home Cookin' | 1969 | Soul | 26 |

| A Gasssss! | 1969 | Soul | - |

| Moody | 1971 | Soul | - |

| Jr. Walker & The All Stars "Live!" | 1967 | Soul | - |

Singles and compilations

Junior Walker & the All Stars achieved significant chart success with their Motown singles during the 1960s and early 1970s, blending raw R&B energy with infectious dance grooves that propelled several tracks to the upper echelons of both the Billboard Hot 100 and R&B charts.[16] Their debut hit, "Shotgun," released in 1965, exemplifies this breakthrough, peaking at #4 on the Hot 100 and #1 on the R&B chart for four weeks while spending 14 weeks overall on the latter.[37] Follow-up singles like "Do the Boomerang" in late 1965 reached #36 on the Hot 100 and #10 on the R&B chart, showcasing their knack for uptempo, sax-driven party anthems.[43] The group's momentum continued with tracks such as "Shake and Fingerpop" (1965, #29 Hot 100, #8 R&B), which captured their signature gritty soul sound and encouraged audience participation through its rhythmic instructions.[44] By 1969, "What Does It Take (To Win Your Love)" marked another peak, hitting #4 on the Hot 100 and #1 on the R&B chart, while "These Eyes" (1969) climbed to #16 on the Hot 100 and #3 on the R&B chart, demonstrating their versatility in slower, emotive ballads.[37] Later efforts included "Gotta Hold On to This Feeling" (1970, #24 Hot 100, #1 R&B) and the final charting single "Gimme That Beat (Part 1)" (1973, bubbling under at #101 Hot 100, #50 R&B), reflecting a shift toward funkier arrangements amid changing musical tastes.[43] Internationally, several singles performed well in the UK, with "Road Runner" (1966) reaching #12, "What Does It Take (To Win Your Love)" at #13, and "Take Me Girl, I'm Ready" (1973) at #16 on the Official Singles Chart.[45]| Year | Single | Hot 100 Peak | R&B Peak | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Shotgun | #4 | #1 | B-side: "Cleo's Mood"; certified gold. |

| 1965 | Do the Boomerang | #36 | #10 | B-side: "Tune Up"; non-album single initially. |

| 1965 | Shake and Fingerpop | #29 | #8 | B-side: "Cleo's Back"; from Soul Session. |

| 1969 | What Does It Take (To Win Your Love) | #4 | #1 | Written by Johnny Bristol; major international hit. |

| 1969 | These Eyes | #16 | #3 | Cover of The Guess Who; ballad shift. |

| 1970 | Gotta Hold On to This Feeling | #24 | #1 | Upbeat soul track. |

| 1973 | Gimme That Beat (Part 1) | #101 | #50 | Final chart entry; funk-oriented. |