Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Kadima

View on Wikipedia

Kadima (Hebrew: קדימה, lit. 'Forward') was a centrist and liberal[3] political party in Israel. It was established on 24 November 2005 by moderates from Likud largely following the implementation of Ariel Sharon's unilateral disengagement plan in August 2005,[4] and was soon joined by like-minded Labor politicians.[5]

Key Information

With Ehud Olmert as party chairman following Sharon's stroke, it became the largest party in the Knesset after the 2006 elections, winning 29 of the 120 seats, and led a coalition government.

Kadima also won the most seats in the 2009 elections under Tzipi Livni's leadership. It was originally in opposition to the Likud-led coalition government under Benjamin Netanyahu. Kadima was briefly a member of the coalition with Netanyahu, joining the government in May 2012 after striking a deal with Netanyahu;[6] however, Kadima returned to the opposition two months later, leaving the government over a dispute over the Tal Law.[7]

Livni was defeated by the more conservative Shaul Mofaz in the March 2012 leadership election. The party's progressive wing, under Livni's leadership, broke away at the end of 2012 to form the new centre-left Hatnua party.[8][9][10] In the 2013 elections, Kadima became the smallest party in the Knesset, winning only two seats and barely passing the electoral threshold. The party ceased its political activities in March 2015 when it chose to not contest the 2015 elections.

History

[edit]Formation

[edit]

The party was founded by Sharon after he formally left Likud on 21 November 2005 to establish a new party that would grant him the freedom to carry out the disengagement plan—removing Israeli settlements from Palestinian territory and fixing Israel's borders with a prospective Palestinian state.

The name Kadima (literally: "Forward") emerged within the first days of the split and was favored by Sharon. However, the party was initially named "National Responsibility" (Hebrew: אחריות לאומית, Ahrayaut Leumit),[11] which was proposed by Justice Minister Tzipi Livni and endorsed by Reuven Adler, Sharon's confidante and strategy adviser. Although "National Responsibility" was regarded as provisional, subsequent tests conducted with focus groups proved it more popular than Kadima.[citation needed] However, on 24 November 2005 the party registered as Kadima.

The title Kadima may have had a symbolic connotation for many Israelis who associated it with the Hebrew battle cry, meaning 'forward march,' but it was common in Israeli political rhetoric. It had been used by early Zionist leader Nathan Birnbaum, and was the motto of the Jewish Legion of World War I formed by Ze'ev Jabotinsky and Joseph Trumpeldor. The name was criticised by Shinui leader Yosef Lapid, who compared it to Benito Mussolini's newspaper Avanti (Italian for "Forward").[12]

On the day after its founding, Kadima had nearly[clarification needed] 150 members, mostly defectors from Likud.[13] Several Knesset members from Labor, Likud, and other parties joined the new party, including cabinet ministers Ehud Olmert, Tzipi Livni, Meir Sheetrit, Gideon Ezra and Avraham Hirschson. Deputy ministers Ruhama Avraham, Majalli Wahabi, Eli Aflalo, Marina Solodkin, Ze'ev Boim and Yaakov Edri also joined, along with Likud MKs Roni Bar-On and Omri Sharon. Former Histadrut chairman Haim Ramon of Labor decided to join shortly thereafter.

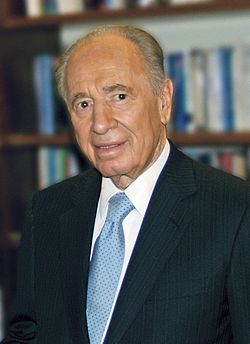

On 30 November 2005, former Prime Minister Shimon Peres left the Labor Party after more than 60 years with the party and joined Kadima to help Sharon pursue the peace process. In the wake of Sharon's poor health, there was speculation that Peres might take over as leader of Kadima. One poll suggested the party would win 42 seats in the March 2006 elections with Peres as leader compared to 40 if led by Ehud Olmert. Most senior Kadima leaders were former members of Likud and indicated their support for (former Likud) Olmert as Sharon's successor.

Doubts following Sharon's medical problems

[edit]The ramifications of Sharon's close identification with Kadima moved the party in an unexpected direction due to his mounting medical problems, which began only a few weeks after Kadima was formed. First, Sharon was hospitalized on 18 December 2005 after reportedly suffering a minor stroke.[14] This introduced a serious element of uncertainty for Sharon's and Kadima's supporters.

During his hospital stay, Sharon was also diagnosed with a minor hole in his heart and was scheduled to undergo a cardiac catheterization to fill the hole in his atrial septum on 5 January 2006. However, on 4 January 2006, 22:50 Israel Time (GMT +0200), Sharon suffered a massive hemorrhagic stroke, and was evacuated to Hadassah Ein Kerem hospital in Jerusalem to undergo brain surgery.

Acting Prime Minister Ehud Olmert succeeded him as Prime Ministerial candidate. Without Sharon, there was uncertainty about the future of the party. Nevertheless, three polls taken shortly after Sharon's illness showed that Kadima continued to lead its rivals by large margins.[15] Later polls showed Kadima strengthening its power base further, particularly amongst left wing voters who had opposed Sharon in the past.

In government

[edit]On 16 January 2006, party members chose Ehud Olmert as acting chairman for the March elections.[16] Kadima won 29 seats, and was asked to form a government by president Moshe Katsav. Olmert formed a coalition with Labor, Shas and Gil, the government being sworn in on 4 May.

Yisrael Beiteinu joined the coalition in October 2006, but left again in January 2008 in protest at negotiations with the Palestinian Authority.

In opposition

[edit]Olmert resigned as party leader in 2008, resulting in a leadership election, held on 17 September. The vote was won by Tzipi Livni, who beat Shaul Mofaz, Meir Sheetrit and Avi Dichter. Following her victory, Livni failed to form a coalition government, as she refused to agree to Shas' demands, resulting in early elections in February 2009. In the elections Kadima remained the largest party in the Knesset, winning 28 seats, one more than Likud. However, Likud's Netanyahu was asked to form a government by President Peres following talks with delegations from all parties represented in the Knesset.

Split

[edit]Livni lost the leadership of Kadima to Shaul Mofaz, considered the leader of the party's right wing,[17][18] in a leadership election in March 2012.[19] In November, Livni, supported mainly by Kadima's dovish flank,[20][21][22][23] left Kadima with seven other Kadima MKs to form a new centrist political party, Hatnua.[24]

In the 2013 legislative election, Kadima lost almost 90% of its vote share from 2009. The party narrowly avoided being ejected from the Knesset, crossing the 2% threshold by just a few hundred votes. The party was reduced to just two MKs, Mofaz and Yisrael Hasson, making it the smallest of the 12 factions in the chamber. Prior to the 2015 elections Mofaz retired from politics after Kadima decided against joining the Zionist Union alliance.[25] Hasson had already left the Knesset in 2013 to become chairman of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Following Mofaz's retirement, Akram Hasson was elected party leader, becoming the first Druze leader of a predominantly Jewish party.[26] However, his leadership was short-lived, with Hasson soon quitting the party to join the Kulanu list,[27] receiving the 12th slot. Kadima subsequently opted to sit out the election.[28]

Platform

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism in Israel |

|---|

|

- The Israeli nation has a national and historic right to the whole of Israel. However, in order to maintain a Jewish majority, part of the Land of Israel must be given up to maintain a Jewish and democratic state.

- Israel shall remain a Jewish state and homeland. Jewish majority in Israel will be preserved by territorial concessions to Palestinians.

- Jerusalem and large settlement blocs in the West Bank will be kept under Israeli control.

- The Israeli national agenda to end the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and achieve two states for two nations will be the road map. It will be carried out in stages: dismantling terror organizations, collecting firearms, implementing security reforms in the Palestinian Authority, and preventing incitement. At the end of the process, a demilitarized Palestinian state devoid of terror will be established.

- Israel's political system will be modified to ensure stability. One possibility to achieve this goal would be to hold primary, regional and personal elections to the Knesset and the Prime Minister's office.

- Kadima would not rule out a future coalition partnership with any Israeli political party or person.

- promoting equality for minorities

- negative income tax and national pension

- increasing social security benefits and national health insurance

- civil marriage for same-sex couples

- reform of police

Political objectives and policies

[edit]In the early stages, the policies of Kadima directly reflected the views of Ariel Sharon and his stated policies.

Early statements from the Sharon camp reported by the Israeli media claimed that they were setting up a truly "centrist" and "liberal" party. It would appear that Sharon hoped to attract members of the Knesset from other parties and well-known politicians regardless of their prior beliefs provided they accepted Sharon's leadership and were willing to implement a "moderate" political agenda.

On the domestic front, Sharon had shown a tendency to agree with his past political partner, the pro-secular and outspokenly anti-religious Shinui party (his allies in the 2003 government), which sought to promote a secular civil agenda as opposed to the strong influence of Israel's Orthodox and Haredi parties. One of the Haredi parties, United Torah Judaism, joined Sharon's last coalition at the same time as the Labor Party, after Shinui had left Sharon's original governing coalition. In the past, Shinui had also called itself a "centrist" party because it rejected both Labor's socialism (its economic policies were free-market) and the Likud's opposition to a Palestinian state (however, from an international standpoint, Shinui may have actually been on the centre-right).

Justice Minister Tzipi Livni reportedly told Israel Army Radio that Kadima intended to help foster the desire for a separate Palestinian state, a move applauded by leftist Yossi Beilin.[citation needed]

Sharon was one of the prime architects pushing for the construction of the Israeli West Bank barrier that has been criticized by left-wing and right-wing Israeli politicians, but was a cornerstone of Sharon's determination to establish Israel's final borders, which he saw himself as uniquely suited to do in the so-called "Final Status" negotiations.

In a 22 November 2005 press conference, Sharon also mentioned that he favored withdrawing from untenable Israeli settlements in the West Bank, although he declined to give an actual timeline or specifics for the proposed action.[29]

Kadima favors continuing a market-based economy with adequate welfare benefits.[30][31]

Place in the political spectrum

[edit]There has been some debate over where Kadima lies on the political spectrum. Many in the Western media use the term centrist,[32][33][34][35] (in that it is positioned between the Labor Party and Likud). Over the last thirty years, Israel has seen a movement by both the right and the left towards the center. Founder Ariel Sharon spent a career switching between the right of Israeli politics and the left—notably in the 1970s when he served as an aide to then Prime Minister Rabin. Most of its elected membership are former Likud party members, but it also has a number of notable ex-Labor MKs. The previous government of Ehud Olmert was considered left of center, collaborating with the Labor and two sector-socialist parties, Gil and Shas. Following the 2009 elections, with its subsequent political negotiations for a centrist coalition with the Likud and the Labor, it is suggested that the ideological differences of the center-left and center-right in Israel are fairly minor, but the fact that this only lasted 60 days belies this.

When Kadima was trying to form a coalition in 2006, the BBC reported that the new party leaned center-right in economic terms while its main coalition partner, Labor, leaned center-left. Labor wanted the Finance Ministry to push through some costly social reforms. It failed to get it, but still insists that the minimum wage, and pension and health benefits, be raised in Israel. At the time, Labor favored a negotiated land agreement with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, and Kadima had so far refused to speak to any Palestinian leader since the Hamas election and has spoken openly of taking unilateral steps in the West Bank, which the Palestinians oppose. Since then, however, Kadima has directly negotiated with the Palestinian Authority.[36]

Following the 2009 elections, Kadima led the opposition in the Knesset. During the elections, Kadima successfully attracted left-of-center voters, to the dismay of Labor and Meretz leaders, who discouraged their supporters from doing so.[37][38] Neither Labor nor Meretz, who were initially expected to be Kadima's natural allies, recommended Livni as prime minister to Peres, reportedly due to Livni's courting of Avigdor Lieberman's Yisrael Beiteinu party.[39][40] Shimon Peres told Ynet in 2006 that "there is no difference" between Kadima and Labor, and suggested that the two groups unite. He added that neither he nor Kadima founder Ariel Sharon liked the economic policy of Likud chairman Benjamin Netanyahu.[41] The Haaretz diplomatic correspondent Aluf Benn suggested in November 2009, that Kadima does not have any ideological differences with the Labor Party that would prevent a merger.[42]

Leaders of Kadima

[edit]| # | Image | Leader | Took office |

Left office |

Prime Ministerial tenure |

Knesset elections | Elected/reelected as leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Ariel Sharon | 2005 | 2006 | 2001–2006 | ||

| 2 |  |

Ehud Olmert | 2006 | 2008 | 2006–2009 | 2006 | 2006 (interim leader)[43][44] |

| 3 |  |

Tzipi Livni | 2008 | 2012 | 2009 | 2008 | |

| 4 |  |

Shaul Mofaz | 2012 | 2015 | 2013 | 2012 | |

| 5 |  |

Akram Hasson | 2015 | 2015 | 2015 |

In addition, Shimon Peres, a former head of Labor, served as Deputy Leader, and was elected President as the Kadima candidate.

Knesset election results

[edit]| Election year | Party Leader | Votes | % | Seats won | +/- | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Ehud Olmert | 690,901 | 22.02 (No. 1) | 29 / 120

|

Coalition | |

| 2009 | Tzipi Livni | 758,032 | 22.47 (No. 1) | 28 / 120

|

Opposition | |

| 2013 | Shaul Mofaz | 79,081 | 2.09 (No. 12) | 2 / 120

|

Opposition |

Knesset members

[edit]After the 2013 election the party had two MKs:

- Shaul Mofaz

- Yisrael Hasson replaced by Yuval Zellner in 2014

Former Knesset members

[edit]- Menachem Ben-Sasson (2006–2009)

- Ze'ev Boim (2005–2011)

- Doron Avital (2011–2013)

- Shlomo Breznitz (2006–2007)

- Amira Dotan (2006–2009)

- Haim Ramon (2006–2009)

- Michael Nudelman (2006–2009)

- Ehud Olmert (2005–2009)

- Shimon Peres (2006–2007)

- Uriel Reichman (2006)

- David Tal (2005–2009)

- Avigdor Yitzhaki (2006–2008)

- Tzachi Hanegbi (2006–2010)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Anika Gauja; Emilie van Haute (2014). "Members and Activists of Political Parties in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). International Political Science Association World Congress of Political Science – Panel 'What is party membership?'. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ Sharon Weinblum (2015). Security and Defensive Democracy in Israel: A Critical Approach to Political Discourse. Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-317-58450-6.

- ^ Emilie van Haute; Anika Gauja (2015). Party Members and Activists. Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-317-52432-8.

- ^ John Vause; Guy Raz; Shira Medding (22 November 2005). "Sharon shakes up Israeli politics". CNN. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Shipman, Tim; Kraft, Dina (14 February 2009). "Obama ready to press Israeli parties to form unity government". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Jodi Rudoren, Leader of Israel Centrist Party Kadima Agrees to Join Netanyahu's Coalition, The New York Times (8 May 2012).

- ^ Kadima quits Israel government over conscription law, BBC News (17 July 2012).

- ^ Jonathan Lis (25 July 2012). "Kadima's left flank delays schism due to problems in recruiting enough MKs". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Jonathan Lis (24 July 2012). "Haim Ramon seeking to form Kadima breakaway faction under Livni's leadership, sources say". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Gil Hoffman (19 July 2012). "Kadima not splitting – for now". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Hoffman, Gil (21 November 2005). "'National Responsibility' name of PM's new party; NRP to protest". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Gil Hoffman; Tovah Lazaroff (25 November 2005). "Shinui headed for oblivion". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ David Krusch (22 November 2005). "Ariel Sharon Forms New Political Party". Jewish Virtual Library. Archived from the original on 2 December 2005.

- ^ "Israel's Sharon suffers a stroke". BBC News. 18 December 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Israel's Kadima could win under Olmert". Angus Reid. 9 January 2006. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006.

- ^ "Comatose Sharon 'moves eyelids'". BBC News. 16 January 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Rebecca Anna Stoil (22 June 2009). "Rivlin shelves powder keg 'Mofaz Law'". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Attila Somfalvi (11 May 2012). "Likud ministers: PM using Kadima". Ynet. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Elad Benari (28 March 2012). "Mofaz Wins Kadima Leadership, Calls on Livni to Stay". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Mati Tuchfeld (27 July 2012). "The idiot's guide to Israel's political Rubik's Cube". Israel Hayom. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Mati Tuchfeld (12 April 2012). "When Shaul Mofaz was a settler". Israel Hayom. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Leslie Susser (8 August 2012). "The rise and fall of Kadima". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Gil Hoffman (22 July 2012). "Kadima may split as MKs take positions in gov't". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Yuval Karni (2 December 2012). "Livni secures 7 MKs to split Kadima". Ynet. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Israel election updates / Likud: Livni wrong on Congress' Iran sanctions". Haaretz, 27 January 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Elad Benari (28 January 2015). "Mofaz Resigns from Politics". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Elad Benari (1 February 2015). "Mofaz: My Biggest Mistake Was Joining Netanyahu's Coalition". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ רשימות המועמדים לכנסת [Lists of candidates for the Knesset]. Knesset Central Elections Committee (in Hebrew). 1 February 2015.

- ^ Nissan Ratzlav-Katz (22 November 2005). "PM Sharon: We Are Committed to the Road Map". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Political Party Platforms" (PDF). Israelvotes.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ "Israeli political parties". BBC News. 5 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Marcus, Jonathan (5 January 2006). "Can Kadima survive without Sharon?". BBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Israeli media: Kadima wins at polls". CNN. 28 March 2006. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Joshua Mitnick (28 March 2006). "New worldview shapes vote in Israel". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (6 January 2006). "Centrist Cause in Israel Seeks New Leader". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Adler, Katya (3 May 2006). "Analysis: Israel's new coalition". BBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Mazal Mualem (9 February 2009). "Elections 2009 / Kadima: Center-left voters will pick us to ensure Likud defeat". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Roni Singer-Heruti (4 February 2009). "New Movement-Meretz polls shows it losing undicided women's vote to Livni". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Mazal Mualem; Yuval Azoulay; Yair Ettinger; Jack Khoury (18 February 2009). "Lieberman not expected to recommend either PM candidate". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Yair Ettinger; Lily Galili; Yossi Verter; Mazal Mualem (12 February 2009). "Likud may offer top spots to Kadima, Lieberman in bid to form quick coalition". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Attila Somfalvi (5 April 2006). "Peres: Kadima, Labor should unite". Ynet. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ Aluf Benn (11 February 2009). "For the sake of peace, Labor and Kadima must merge". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Acting Israeli leader to head Sharon's party". The New York Times. 16 January 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ "Kadima picks Olmert as interim chief". Al Jazeera. 16 January 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

External links

[edit]- Kadima Knesset website

- Kadima hoping to hold onto power CNN

- Sharon shakes up Israeli politics CNN 22 November 2005

- Peres Hails Sharon's Leadership as He Supports New Party

- Sharon quits Likud Interview with Ariel Sharon

- Sharon's New Party Shuffles the Political Deck, Setting Off a Scramble for Israeli Elections

Kadima

View on GrokipediaHistory

Formation and Founding Principles

Kadima was established on November 21, 2005, when Prime Minister Ariel Sharon announced the creation of a new centrist political party after resigning from the leadership of the Likud party.[2] The split from Likud stemmed primarily from internal opposition within the party to Sharon's unilateral disengagement plan from Gaza, implemented in August 2005, which had led to significant rifts and a leadership struggle.[1][8] Sharon's departure was precipitated by at least half of Likud members rejecting the disengagement, prompting him to seek a platform more aligned with his pragmatic approach to security and territorial issues.[8] The party's founding principles were publicly outlined on November 28, 2005, emphasizing the preservation of Israel's Jewish majority through territorial concessions if necessary to maintain democratic character and security.[9][10] Kadima advocated for delineating permanent borders, continuing withdrawals from parts of Gaza and the West Bank, and ensuring maximum security while affirming Israel's historic right to the whole of the land, balanced against the need for a demilitarized Palestinian state.[9][8] The platform supported a two-state solution to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, combining Zionist ideology with bold actions against terrorism and separation from Palestinians, while promoting social welfare and economic policies aimed at growth.[1][11] Positioned as a "forward"-moving centrist force, Kadima sought to transcend the traditional dominance of Likud and Labor by attracting moderate voters disillusioned with ideological extremes, focusing on national responsibility and pragmatic governance over rigid partisanship.[9] This approach reflected Sharon's vision of unilateral steps for peace and security when bilateral negotiations stalled, prioritizing Israel's Jewish and democratic nature amid ongoing threats.[12][8]Sharon's Incapacity and Transition to Olmert

Ariel Sharon, the founder and leader of Kadima, suffered a massive stroke on January 4, 2006, entering a coma from which he never recovered. [13] Ehud Olmert, serving as Sharon's deputy prime minister, was immediately designated acting prime minister on January 5, 2006. [14] Two weeks later, on January 16, 2006, Kadima's central committee confirmed Olmert as the party's interim leader, ensuring continuity amid the leadership vacuum. Sharon was initially declared temporarily incapacitated by Attorney-General Menahem Mazuz on January 6, 2006. On April 11, 2006, after 97 days of assessing his condition, the Israeli cabinet unanimously declared Sharon permanently incapacitated, formally terminating his tenure as prime minister. [15] [16] This decision elevated Olmert to interim prime minister effective April 11, 2006, solidifying his control over both the government and Kadima as the party prepared for national elections. [17] The transition preserved Kadima's momentum from Sharon's disengagement initiatives, with Olmert committing to pursue similar pragmatic policies on security and territorial concessions. [18]