Recent from talks

All channels

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Be the first to start a discussion here.

Welcome to the community hub built to collect knowledge and have discussions related to Left fielder.

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Left fielder

View on Wikipediafrom Wikipedia

Not found

Left fielder

View on Grokipediafrom Grokipedia

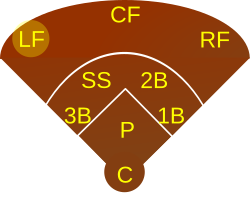

In baseball, a left fielder (abbreviated LF) is a defensive outfielder who covers the left portion of the outfield, located between the shortstop and third baseman lines when viewed from home plate.[1][2] The position, designated as number 7 in official scorekeeping, involves patrolling the area farthest from the infield to catch fly balls, field grounders, and prevent base runners from advancing on hits to that side of the field.[1][3]

Left fielders share responsibilities with the center and right fielders to support the infield, including backing up throws to third base and relaying balls during cutoffs.[2] Unlike the center fielder, who requires exceptional speed and range to cover overlapping territories, or the right fielder, who often needs a cannon arm for long throws to third or home, the left fielder typically demands less athleticism in those areas because, although more balls are pulled to left field by right-handed batters, throws from left are generally shorter distances to second or third base.[1][3][4] However, a strong throwing arm remains valuable for left fielders to gun down runners attempting extra bases, particularly in ballparks with expansive left-field dimensions.[1]

Historically, the left field position has been considered the least defensively demanding in the outfield, often assigned to players with superior hitting skills but average fielding ability, though park-specific adjustments can elevate its importance—such as placing stronger-armed players there in ballparks with deep left fields.[1] Notable left fielders, from Babe Ruth's power-hitting era to modern stars like Yordan Alvarez, exemplify how the role balances offensive contributions with reliable defense.[1] The third-base umpire oversees fair/foul calls along the left-field line, ensuring accurate boundary judgments during play.[2]