Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

First baseman

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2016) |

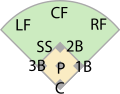

A first baseman, abbreviated 1B, is the player on a baseball or softball team who fields the area nearest first base, the first of four bases a baserunner must touch in succession to score a run. The first baseman is responsible for the majority of plays made at that base. In the numbering system used to record defensive plays, the first baseman is assigned the number 3.

Also called first sacker or cornerman, the first baseman is ideally a tall player who throws left-handed and possesses good flexibility and quick reflexes. Flexibility is needed because the first baseman receives throws from the other infielders, the catcher and the pitcher after they have fielded ground balls. In order for the runner to be called out, the first baseman must be able to stretch towards the throw and catch it before the runner reaches first base. First base is often referred to as "the other hot corner"—the "hot corner" being third base—and therefore, like the third baseman, he must have quick reflexes to field the hardest hit balls down the foul line, mainly by left-handed pull hitters and right-handed hitters hitting to the opposite field.

Fielding

[edit]

Good defensive first basemen, according to baseball writer and historian Bill James, are capable of playing off first base so that they can field ground balls hit to the fair side of first base.[citation needed] The first baseman then relies upon the pitcher to cover first base to receive the ball to complete the out. Indications of a good defensive first baseman include a large number of assists and a low number of throwing errors by other infielders.

In general

[edit]The nature of play at first base often requires first basemen to stay close to the bag to hold runners or to reach the bag before the batter. First basemen are not typically expected to have the range required of a third baseman, shortstop, second baseman or an outfielder. As a result, first base is not usually perceived to be as physically demanding as other positions. However, it can also be a very hard position to play; a large amount of concentration and timing is required. Though many play at first base their entire career, occasionally veteran players move to first base to extend their careers or to accommodate other recently acquired players. Facing a possible trade or a considerable reduction in playing time, a player may opt to move to first base instead. Catchers and corner outfielders sometimes move to first base due to deteriorating health or if their fielding abilities at their original position are detrimental to the team.

Position

[edit]Unlike the pitcher and catcher, who must start every play in a designated area (the pitcher must be on the pitcher's mound, with one foot in contact with the pitcher's rubber, and the catcher must be behind home plate in the catcher's box) the first baseman and the other fielders can vary their positioning in response to what they anticipate will be the actions of the batter and runner(s) once play begins.[1]

When first base is not occupied by a baserunner, the first baseman usually stands behind first base and off the foul line. The distance he plays from the base and foul line is dependent on the current hitter and any runners on base. The exact position may also depend on the first baseman's experience, preference, and fielding ability. For a known right-handed pull hitter, the first baseman might position himself further towards the second baseman's normal fielding position. For a known left-handed pull hitter, the first baseman will position himself closer to the foul line to stop a ball hit down the line.

To protect against a bunt on the first base side of the infield, the first baseman will position himself in front of the base and move towards the hitter as the pitch is thrown. As soon as the pitcher commits to throwing towards home plate, the first baseman will charge towards the hitter to field the bunt. During these plays, it is the responsibility of the second baseman to cover first base.

With a base runner present at first base, the first baseman stands with their right foot touching the base to prepare for a pickoff attempt. Once the pitcher commits to throwing towards home plate, the first baseman comes off the bag in front of the runner and gets in a fielding position. If the bases are loaded, or if the runner on first base is not a base stealing threat, the first baseman will position himself behind the runner and appropriate for the current batter.

When waiting for a throw from another player, the first baseman stands with their off-glove foot touching the base, then stretches toward the throw. This stretch decreases the amount of time it takes the throw to get to first and encourages the umpire to call close plays in favor of the fielding team. Veteran first basemen are known to pull off the bag early on close plays to convince the umpire that the ball reached their glove before the runner reached first base. The first baseman also has the responsibility of cutting off throws from any of the three outfield positions on their way to home plate. Though highly situational, the first baseman usually only receives throws from the center or right fielder.

Double play

[edit]The first baseman is usually at the end of a double play, though he can be at the beginning and end of a double play. Unusual double plays involving the first baseman include the 3–6–3, 3–4–3, 3–2–3, or a 3–6–1 double play. In a 3–6–3 or 3–4–3 double play, the first baseman fields the ball, throws to second, where the shortstop (6) or second baseman (4) catches the ball to make the first out and then throws back to the first baseman who reaches first base in time to tag first base before the batter reaches first base. For a 3–2–3 double play, the bases must be loaded for the force-out at home plate or the catcher must tag the runner coming from third base out. With a force-out at home plate, the first baseman fields the ball, throws to the catcher, the catcher steps on home plate for the first out, then he throws it back to the first baseman to complete the double play. The 3–2–3 double play with a tag out at home plate is usually not attempted because of the possibility of the catcher not being able to tag the runner and/or block the plate. If the runner at third base is known as a good or fast baserunner, the first basemen will make considerable effort to make sure the third base runner does not advance to home plate for a run by "looking" him back to third base. The primary goal of the first baseman in this instance is to ensure the runner does not advance and that the team records at least one out, especially in a close game. A 3–6–1 double play is almost like a 3–6–3 or a 3–4–3 double play, but the first baseman is usually playing deep in the infield. Here, the first baseman throws the ball to the shortstop covering second, but the pitcher then has the responsibility of covering first base to receive the throw from the shortstop.

A first baseman can theoretically also make an unassisted double play. There are two ways to achieve this. The first is by catching a line drive and returning to first base to tag the base before a baserunner can return. This is rare because the first baseman is usually slower than most baserunners who generally return to their bases on line drives near any fielder. The second is by getting an infield hit to the right when there is a runner on first, tagging the runner and returning to the first base in time to get the man running towards him.

Left-handed throwing first basemen

[edit]

A left-handed throwing non-pitcher is often converted to or begins their career playing at first base. A left-handed throwing baseball player who is not particularly fast or has a weak arm (and therefore not well suited for playing in the outfield) will usually be relegated to playing first base. This is because the only other positions available to the player (catcher, third base, shortstop or second base) are overwhelmingly held by right-handed throwing players, who can make quicker throws to first base (or, in the case of catchers, third base).

The same advantages of being a right-handed throwing catcher, third basemen, shortstop or second basemen apply to the left-handed first baseman. These advantages surface in plays where the player is required to throw to another infielder after fielding a batted ball. In these instances, a right-hander will be required to turn more towards their target before throwing whereas a left-hander will usually already be positioned to make a throw. However, compared to the advantage for the right-handed throwing third baseman, shortstop, or second baseman, these advantages for the left-handed first baseman are minor because many balls hit to the first baseman are to their right, so that a right-handed first baseman fielding them backhanded does not need to turn after fielding a batted ball to throw it. In addition, a majority of plays only require the first baseman to receive a throw, not to field or throw himself. This is attributed to the overall majority of baseball players batting right-handed, and therefore, a majority of batted balls are hit to the left side of the infield and fielded by the third baseman or shortstop. Left-handed first basemen are also advantageous in attempting to pick off baserunners at first, as the left-hander can catch and tag in one motion, often doing both at the same time, while right-handed first baseman must sweep their glove across their body, costing them a crucial fraction of a second in applying the tag.[2]

First-baseman's mitt

[edit]The first baseman's mitt is similar to a catcher's mitt in that it has extra padding and has no individual fingers. (In shape, it is closer to a mitten than a glove.) It is much larger than the other infielders' gloves; it is wide, very deep, and it is crescent-shaped at its edges, allowing the first-baseman to use the mitt like a scoop in catching errant throws from other players on the infield.

Since many throws to first base are made in great haste, the first baseman must be prepared to catch balls that are either high or low, as well as balls thrown quite a distance to either side, all while maintaining contact with the base (using one foot or the other). This requires a fair amount of agility and physical coordination. Among the most difficult plays a first baseman is normally required to make are the "short hop" and the "tag play", both of which are far easier to execute when the fielder is wearing the first-baseman's mitt rather than another type of glove.

Short hop

[edit]

Every ground ball hit to an infielder becomes a race between the batter-runner and the team in the field; the fielder must catch the batted ball and throw it to first before the batter can reach the base. Consequently, part of the first baseman's job is to step toward the incoming ball and stretch their body so that their catching hand makes contact with it as soon as physically possible. Compared to catching the ball while standing passively on the base, this shaves a fraction of a second from the time the runner has to reach base. When it is thrown too low and bounces before reaching the first baseman, catching the ball is difficult, especially while he is in a "stretch position". A throw caught shortly after its bounce, that is, while the baseball's path, rebounding from the turf, is sharply upward, is called a "short hop". Since a ball that strikes the ground is always subject to the possibility of encountering a pebble or a rut or a spike-mark that sends it in a radically new direction, it is best that the first baseman catch the ball on the short hop by swiping or scooping the ball as close to the ground surface as possible. This technique also minimizes the amount of time required to make the putout.

Tag play

[edit]The second-most-difficult play for a first baseman is the "tag play". Whenever an infielder's throw is so far off the mark that the first baseman must abandon their base to catch it, the first baseman is left with only two options. To put the runner out, he must either lunge back to the base before the runner reaches it, or he must tag the runner before the runner reaches the base. A tag involves touching the runner with the ball (or with the gloved hand holding the ball) before the runner reaches the base. At first base, the typical tag play occurs when the infielder's throw is high and to the left of the first baseman, causing him to jump and stretch their long mitt to catch the ball before it sails into the dugout or the grandstand. The tag is made, after the catch, by swiping the mitt downward, toward the in-coming runner's head or shoulder, often in one fluid motion that is integrated with the act of catching the ball. Performed properly, the tag play can be spectacular to see.

As a career move

[edit]First basemen are typically not the most talented defensive players on a major-league team. Someone who has the agility, throwing arm, and raw speed to play another fielding position usually plays somewhere other than first base. Great-hitting catchers may play some games at first base so that they can hit in some games without having to absorb the rigor of catching every game.[according to whom?]

According to Bill James, aside from pitchers and catchers, the most difficult defensive position to play is shortstop, followed by second base, center field, third base, left or right field (depending upon the ballpark), and finally first base as the easiest position.[citation needed] Anyone who can play another position on the field can play first base.

Lou Gehrig is an example of a player who played first base because he was not as strong a fielder as hitter.[3] At or near the ends of their careers, good hitters are often moved to first base as their speed and throwing arms deteriorate, a more talented position player was acquired, or their teams become concerned with the likelihood of injury. Such players include Hall of Famers George Brett, Paul Molitor, Mike Schmidt and Jim Thome (third basemen), Ernie Banks (shortstop), Rod Carew (second baseman), Al Kaline (right fielder), Mickey Mantle (center fielder), Johnny Bench, Joe Mauer, and Mike Piazza (catchers), Stan Musial and Willie Stargell (left fielders). In 2023, Philadelphia Phillies all-star Bryce Harper moved from outfield to first base after undergoing Tommy John surgery; this enabled Harper to return to the field quicker than expected while also lessening the stress of throwing with his surgically repaired right arm. Only rarely does a player begin his major-league career at first base and go elsewhere, as with Jackie Robinson, a natural second baseman who was played at first base in his rookie season so that he would avoid the risk of malicious slides at second base. Hank Greenberg, a natural first baseman for the Detroit Tigers, moved to left field in his 11th major league season (1940) after his team acquired Rudy York, another slugging first baseman who was ill-suited to play anywhere else.[4]

Hall of Famers

[edit]- Dick Allen

- Cap Anson

- Jeff Bagwell

- Jake Beckley

- Jim Bottomley

- Dan Brouthers

- Orlando Cepeda

- Frank Chance

- Roger Connor

- Jimmie Foxx

- Lou Gehrig

- Hank Greenberg

- Todd Helton

- Gil Hodges

- George Kelly

- Harmon Killebrew

- Buck Leonard

- Willie McCovey

- Fred McGriff

- Johnny Mize

- Eddie Murray

- Tony Pérez

- George Sisler

- Mule Suttles

- Ben Taylor

- Bill Terry

- Frank Thomas

- Jim Thome

References

[edit]- ^ Baseball Explained by Phillip Mahony. McFarland Books, 2014. See www.baseballexplained.com Archived August 13, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Left-handed first baseman like Pirates' LaRoche becoming rare". Trib Live.

- ^ Menand, Louis (May 25, 2020). "How Baseball Players Became Celebrities". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ Coffey, Alex. "Tigers move first baseman Hank Greenberg to the outfield". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

First baseman

View on GrokipediaOverview

Role and responsibilities

The first baseman is the infielder positioned at or near first base, primarily responsible for receiving throws from other fielders to record outs on runners attempting to reach the base.[6] This role involves securing the bag on force plays, where the defensive team must touch the base with the ball before the runner arrives.[7] Key defensive responsibilities include catching throws from infielders, stretching to secure errant tosses while keeping one foot on the base, and fielding bunts or ground balls hit near the baseline to prevent advancing runners.[6][8] The first baseman also handles pick-off attempts from the pitcher and may toss the ball underhand to the pitcher covering first on certain grounders.[6] Additionally, the position requires participation in double plays, often by stretching to receive a relay throw from second base.[6] Offensively, the first baseman is typically expected to be a power hitter, batting in the middle of the lineup to drive in runs, as the position demands less lateral range than shortstop or center field.[6][9] This emphasis on hitting stems from the role's focus on stationary defense around the base, allowing for larger, stronger players.[6] Unique statistical metrics for the position highlight its centrality in infield defense: first basemen record the highest number of putouts among infielders, often exceeding 1,000 per season for league leaders, due to the volume of throws they receive.[10] Their fielding percentage, calculated as (putouts + assists) / (putouts + assists + errors), typically ranks among the highest in the infield at around .994 or better for elite performers, reflecting the importance of error-free catches on routine plays.[11][12] On close plays at the bag, the first baseman interacts closely with the first-base umpire, who observes whether the fielder's foot remains on the base while securing the ball in the glove before the runner's foot leaves the ground.[13] This coordination is critical for accurate safe/out calls on bang-bang plays, with the first baseman using a specialized oversized mitt to extend reach without compromising the umpire's view.[6]Historical evolution

The position of first baseman traces its origins to 19th-century baseball, formalized under the Knickerbocker Rules adopted by the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York in 1845, which established first base as a critical station in the base-running circuit spanning four bases arranged in a diamond formation 90 feet apart.[14] In these foundational rules, the first baseman's primary duty involved securing the base with the ball to retire advancing runners, as a player was declared out if the ball reached the hands of an adversary on first base before the runner arrived, emphasizing control of the bag over extended fielding range.[14] This setup integrated the force-out mechanic inherent to the position, where the batter-runner could be retired simply by the fielder touching the base with possession of the ball, a principle that has persisted with minor refinements since the sport's inception.[15] Key rule changes in the 1880s further defined the first baseman's role in managing base paths, including interference provisions that required runners to avoid physical contact with fielders and maintain a direct line to the base, penalizing deviations as outs to protect fielders executing plays at first.[16] The introduction of the foul strike rule in 1901 by the National League, which counted foul balls as strikes (except bunts after two strikes), shortened at-bats and contributed to the defensive-oriented dead-ball era (pre-1920), where first basemen functioned as versatile all-around players proficient in handling bunts, steals, and close plays rather than relying on power at the plate.[17] During this period, low-scoring games prioritized fielding agility and strategic "inside baseball" tactics, positioning first basemen as key defensive anchors without the expectation of home run production.[18] The shift to the live-ball era after 1920, prompted by rule adjustments such as banning the spitball, cleaning soiled balls more frequently, and introducing a livelier cork-centered baseball, dramatically increased offensive output and transformed first basemen into specialized power hitters capable of driving in runs with extra-base hits.[19] This evolution favored sluggers who could stretch the position's defensive demands with superior hitting, contrasting the dead-ball emphasis on versatility. The American League's adoption of the designated hitter rule in 1973 extended this trend by allowing non-pitching position players, including first basemen, to prioritize offensive specialization, as weak-hitting pitchers were removed from the batting order, thereby reducing overall fielding pressures on the lineup and boosting run production.[20] In the post-2010 era, advanced analytics and data-driven strategies refined first base tactics through defensive shifts, often positioning first basemen closer to second base against opposite-handed batters—particularly right-handed hitters prone to pulling the ball—to exploit spray-chart patterns and maximize out probabilities on ground balls.[21] These shifts proliferated from around 3,000 instances in 2010 to over 40,000 by 2018, representing a tactical evolution blending historical base control with probabilistic optimization. However, MLB prohibited such extreme infield shifts starting in the 2023 season, requiring at least two infielders on each side of second base prior to the pitch, which has led to a return to more traditional positioning for first basemen.[22]Fielding fundamentals

Positioning and footwork

The first baseman's standard positioning places them approximately 10 to 15 feet off the foul line and even with or slightly in front of the base, oriented toward second base to cover ground balls through the 1-2 hole and prepare for throws.[23] This setup allows optimal range for fielding while maintaining proximity to the bag for quick transitions. Variations occur based on game situations: for bunt defense, the first baseman shifts closer to the baseline and nearer the plate to charge potential bunts; during pickoff attempts, they move onto the bag with one foot planted to hold the runner while keeping eyes on the pitcher.[24] Footwork fundamentals emphasize an athletic stance off the bag to react swiftly to grounders or throws. From this position, they take quick, short steps toward the bag on incoming throws, squaring the body to face the ball's trajectory before establishing contact with the base using the appropriate foot—typically the inside foot for right-handed throwers to maintain balance.[25] For stretch plays, the technique involves planting the toe of the rear foot on the base while extending the lead leg and glove arm toward the throw's path, enabling catches of high or wide pitches without pulling off the bag too early, thus preserving the force out.[25] Beyond the immediate bag area, the first baseman covers foul territory along the first-base line, positioning to field fair-foul bouncers or errant throws that veer into foul ground.[26] They also back up throws to home plate, particularly from right field, by moving behind the plate at an angle to retrieve passed balls or wild pitches, preventing runners from advancing extra bases.[27] Training emphasizes drills that build balance and quick pivots, essential for force outs at the bag. Common exercises include wall-ball throws to simulate short hops while maintaining foot placement on the base, promoting stable extension; partner tosses for stretch reactions, focusing on toe-toe pivots to square up without losing contact; and agility ladder runs combined with bag sprints to enhance rapid steps and body control during transitions to the stretch position.[28] These drills reinforce the need for explosive yet controlled movements, ensuring the first baseman can pivot efficiently to tag runners or transition to throws if needed.[25]Receiving throws and tags

The first baseman's primary responsibility in receiving throws is to provide a clear target while maintaining contact with the base to ensure an out on force plays. To execute this, the fielder squares their body to the thrower with both heels on the bag, presenting the mitt at chest height to offer the largest possible target for infielders under pressure.[25] Once the throw is in flight, the first baseman absorbs the impact using a "give" motion, pulling the mitt back slightly toward the body to cushion the ball and prevent it from popping out, which enhances control and allows for quick transitions if needed.[29] In tag play execution, particularly when a runner overruns first base, the first baseman must touch the base with their foot while simultaneously tagging the runner if they step off before returning. Per MLB Official Rule 5.09(b)(4), a batter-runner who reaches first base safely may overrun without liability to be tagged out, but they become vulnerable if they do not immediately return to the base; the first baseman can then apply the tag to record the out.[30] This requires precise timing, as the fielder keeps one foot on the bag during the catch and pivots to tag only after confirming the runner's position. Handling errant throws demands quick adjustments without compromising the base. For low bounces, the first baseman drops into a scoop position, aligning the mitt low to the ground and using a sweeping motion from the dirt upward to secure the ball while keeping the toe on the bag.[8] High throws require reaching upward with the glove arm extended fully, but the fielder avoids overextending by shifting weight forward only after the ball's trajectory is clear, ensuring the base foot remains planted to avoid a pulled foot call.[25] Umpires officiate these plays with specific signals and procedures for appeals. On a close safe call at first base potentially involving a pulled foot, the base umpire extends both arms forward and sweeps them outward with palms down, verbalizing "safe" and often adding "he pulled his foot" to clarify the decision.[31] For out calls, a clenched right fist delivers a sharp hammer motion. Appeals for a pulled foot are handled by the defense verbally requesting a check from the umpire, who may confer with partners if needed; the base umpire rules based on observed foot contact at the moment of the catch.[32] A common error in receiving throws is overextending prematurely, known as stretching too early, which often results in the first baseman's foot leaving the bag before securing the ball and leads to safe calls on runners. This mistake compromises balance and limits adjustments to imperfect throws.[33] In the post-2015 replay era, such close plays at first base have seen overturn rates of approximately 60% on challenged calls in 2015.[34]Participation in double plays

The first baseman is integral to executing double plays, most notably in the standard 3-6-3 configuration, where they field a ground ball hit directly to them (denoted as position 3), step on first base if necessary, throw to the shortstop (position 6) covering second base to force out the runner from first, and then receive the return throw at first base for the second out on the batter-runner.[35] This sequence demands exceptional footwork and arm strength, as the first baseman must generate velocity on the initial throw across the diamond while preparing to stretch for the incoming relay.[36] Left-handed first basemen often execute this more fluidly, fielding the ball and releasing toward second without a full pivot, which reduces the time needed compared to right-handers who must rotate their body.[36] An alternative configuration is the 3-4-3 double play, used when the second baseman (position 4) covers second base instead of the shortstop; here, the first baseman fields the grounder, throws to the second baseman for the force out at second, and catches the return throw at first to retire the batter.[37] This variation occurs less frequently than the 3-6-3 but requires similar quick decision-making, especially if the ground ball's trajectory favors the second baseman's positioning.[38] Timing and pivoting are critical in both setups, with the first baseman needing a rapid release after tagging the base to avoid obstructing the runner's path, as per MLB rules prohibiting unnecessary interference. The pivot motion—minimal for lefties but involving a 180-degree turn for righties—must be efficient to maintain balance and accuracy on the throw to second.[36] Situational awareness guides these actions; for instance, if the runner at second hesitates, the first baseman may fake a throw to second to freeze the runner or initiate a rundown by tossing to the shortstop, preventing advancement while securing the double play.[39] Historically, double plays involving the first baseman, such as 3-6-3 configurations, have accounted for a notable portion of all MLB double plays; analysis of play-by-play data from 1954 to 2007 shows 3-6-3 plays comprising about 2.8% of total double plays.[35] In 2023, first basemen participated in 3,690 double plays league-wide, underscoring their defensive impact despite the position's offensive emphasis.[40]Equipment and specialized techniques

First baseman's mitt design

The first baseman's mitt is distinguished by its larger size, typically measuring 12 to 13 inches in length, which provides a broader catching surface compared to standard fielding gloves used at other positions.[41] This design includes an open webbing configuration, often a single or dual post style, creating a webbing-free pocket that enhances visibility of incoming throws and allows for effective scooping of low or errant balls.[41] Additionally, the mitt features extended padding around the wrist and heel area, such as dual-density memory foam liners, to support prolonged stretches and protect against impacts during extended reaches.[42] Modern mitts often incorporate advanced materials like kip leather or synthetic hybrids for improved flexibility and durability.[43] Constructed primarily from high-quality leather, the mitt emphasizes flexibility in its structure, with a one-piece solid web and curved fingertips that form a deep, rigid pocket ideal for securing throws.[44] This contrasts with the closed webbing found on pitchers' gloves, which conceals ball grip but restricts scooping motion; the first baseman's open design prioritizes quick ball retention and release.[45] The evolution of the first baseman's mitt began with standard padded gloves in the late 1800s, when players like outfielders and first basemen adopted flesh-colored leather protectors to handle sharp line drives.[46] By the early 1900s, as scooping techniques for low throws gained prominence—popularized by innovative first basemen such as Hal Chase—specialized mitts emerged with deeper pockets and reinforced padding to accommodate these plays.[47] Full specialization occurred by the 1920s, with manufacturers introducing larger, fingerless designs tailored for the position's demands.[48] Major League Baseball regulations stipulate that the first baseman's mitt must be a leather glove or mitt no longer than 13 inches from top to bottom and no wider than 8 inches across the palm, ensuring fair play without excessive advantage.[49] No rigid attachments or materials are permitted, maintaining flexibility and preventing alterations that could impede umpires' visibility or game integrity.[49] Players often customize their mitts for personal fit and style, adding embroidery for names or numbers on the leather and adjusting lacing colors or patterns to match team uniforms or preferences.[45] These modifications, while cosmetic, can enhance grip and comfort without violating rules. The mitt's design supports techniques like handling short hops and executing tags, though its primary purpose remains optimized for stretch receptions.[41]Handling short hops

Handling short hops is a fundamental skill for first basemen, involving the precise fielding of low-bouncing throws from infielders to secure outs on ground balls. The technique requires the first baseman to maintain contact with the base using the throwing-side foot while striding forward with the glove-side foot to reach the ball. The mitt is positioned low, often starting near or on the ground, and pushed through the ball in an upward motion to scoop or "basket catch" the hop, absorbing the bounce into the deep pocket of the specialized first baseman's mitt. This method, sometimes involving a slight drop to one knee for stability on very low throws, allows the fielder to secure the ball without it skipping away.[50][51] Timing is critical, with the first baseman reading the ball's trajectory approximately 10-15 feet from the base to anticipate the hop and position the mitt as a backstop. The fielder attacks the ball aggressively rather than waiting passively, using proper footwork alignment to square the body toward the throw and prevent misalignment that could cause errors. By keeping the glove vertical initially and finishing flat through the bounce, the first baseman minimizes the risk of the ball deflecting off the mitt and bounding into foul territory or the outfield, which could allow the runner to advance. This skill is essential, as many infield throws—particularly from shortstop and third base—arrive as short hops due to the distance and angle involved.[51][50] Practice drills emphasize repetition to build muscle memory and reaction time. A common partner drill involves the coach or teammate throwing short hops from the second base position at game-like speeds up to 80 mph, with the first baseman completing 10 repetitions per set while keeping the throwing foot on the bag; variations include throws to either side to simulate stretches. Wall bounce drills, where the player throws the ball against a wall to create short hops in front of them, help isolate glove work and timing without a partner, focusing on pushing through the bounce. These drills simulate real-game scenarios and improve error reduction by reinforcing the proper angle of reception.[50][52] Adjustments are necessary for varying field conditions to maintain effectiveness. On wet fields, where the ball may skid unpredictably, the first baseman lowers the stance further and uses a firmer glove push to counteract reduced traction and higher bounce irregularity. For hard dirt surfaces, which produce sharper, faster hops, the fielder anticipates quicker trajectory changes by reading the ball earlier and positioning the mitt slightly more forward as a barrier. These adaptations ensure reliable performance across environments, leveraging the mitt's design for secure catches in challenging scenarios.[51]Executing tag plays

In executing tag plays at first base, the first baseman must employ precise positioning and timing during pickoff attempts on runners leading off the base in preparation for steals to second. The first baseman typically positions themselves slightly behind and to the inside of the runner, straddling the bag with their inside foot on or near it to receive the pitcher's throw while maintaining balance for quick movement. Upon catching the ball, they extend the mitt toward the runner's path and swipe horizontally across the chest or midsection to apply the tag, ensuring the glove remains open to secure the ball first before attempting contact. This technique minimizes the risk of the runner evading the tag by diving back to the base and allows for a fluid transition if the runner retreats further.[53] For overrun situations involving the batter-runner, the first baseman waits for the runner to pass the base after a close play, ready to apply the tag if the runner fails to return immediately or shows intent to advance. Under MLB Official Rule 5.09(b)(4), the batter-runner is protected from being tagged out solely for overrunning or oversliding first base provided they return to the base without delay; however, protection ends if they stray more than three feet from the base path to avoid the tag or attempt to go to second, at which point the first baseman can legally tag them out while positioned on or near the bag. This requires the first baseman to read the runner's momentum and hesitation, often stretching the mitt low across the base to intercept any delayed return.[7][54] The first baseman also plays a critical role in rundowns originating from pickoffs or failed steal attempts between first and second base, serving as the primary tagger at the rear base. In standard defensive alignment, the first baseman and pitcher cover first base as the "back" defenders, while the second baseman and shortstop handle the "front" at second; the first baseman receives any throw from the front and applies the tag if the runner retreats to first, or immediately chases if the runner continues toward second to limit the rundown's length. This transition demands quick footwork to avoid obstructing the base path and verbal cues to coordinate with infielders, ensuring the runner is funneled back to the smaller base for an easier out.[55] Replay review has significantly influenced the execution of tag plays at first base, as challenges for tag plays in general have overturned on-field decisions in approximately 47-55% of cases from 2017 to 2025.[56][57] This high reversal rate underscores the need for first basemen to secure clear visual contact with the umpire during tags, as reviews often scrutinize whether the runner's foot remained on the bag or if the tag was applied before the runner's arrival. Managers frequently challenge these plays due to the narrow margins, prompting first basemen to prioritize firm glove pressure and stable positioning to withstand post-play verification.[58] Effective defensive signals enhance tag play execution, particularly in communicating with the catcher regarding throw timing on potential steal or pickoff setups. The first baseman may use subtle verbal calls or glove adjustments visible to the catcher—such as a quick tap on the mitt or a raised hand—to indicate the runner's lead size or readiness to attempt a steal, allowing the catcher to relay pitch-out signals to the pitcher. This coordination ensures the throw arrives precisely when the runner commits, enabling a seamless tag without alerting the baserunner.[59]Variations by handedness

Advantages of left-handed throwers

Left-handed throwers possess a primary biomechanical advantage at first base through their natural ability to stretch toward throws originating from right-handed infielders at second and third base. Positioned with their left foot on the bag and right hand holding the glove toward the infield, they can face home plate directly, minimizing crossover steps and enabling a more fluid reception of the ball while keeping the foot on the base for the out. This setup contrasts with right-handers, who must often twist their body more awkwardly to maintain bag contact during similar plays.[3] The throwing mechanics further enhance this edge, allowing for a quicker release to other bases without excessive pivoting, as the glove hand remains planted on the bag and the dominant left arm swings freely across the diamond. In scenarios like covering bunts or initiating double plays, left-handed first basemen can step directly toward second or third base, reducing the time and error risk compared to right-handers who may need to rotate fully. This efficiency is particularly valuable in high-pressure situations where split-second decisions determine outs.[3] Statistically, left-handed first basemen exhibit a slight fielding advantage due to these positional benefits. Recruitment trends underscore this preference, as left-handers, who represent only about 10% of the general population, have been historically overrepresented at the position relative to their proportion in the general population and among players. However, as of the 2020s, the proportion of left-handed throwing first basemen has been declining due to broader trends in player development and positional versatility.[60] To maximize these advantages, training for left-handed first basemen emphasizes drills focused on left-side pulls, such as ranging exercises to foul territory where grounders require backhand retrievals and quick transitions to the bag. These sessions, often incorporating short-hop simulations and footwork patterns along the baseline, build on their inherent range toward the infield's right side, enhancing overall defensive reliability without overemphasizing less natural movements.[25]Challenges and adaptations for right-handed throwers

Right-handed first basemen encounter a primary challenge in receiving throws from the left side of the infield, requiring an awkward stretch across the body that can compromise balance and increase error risk on pulled or wide throws.[61] This cross-body motion demands precise timing and coordination, as the throwing arm (right hand) must remain ready for potential tags or relays while the glove hand extends leftward.[61] To adapt, right-handed players often employ a "cross-step" footwork technique, stepping the left foot toward the incoming ball to align the body more naturally before stretching, or position themselves slightly to the left of the bag's inside corner for better access to errant throws.[25] Additionally, extending with a longer first baseman's mitt allows greater reach without excessive body twist, maintaining contact with the base via the right foot.[62] These adjustments help mitigate the inherent awkwardness compared to left-handed counterparts, who face throws more squarely.[36] Despite these obstacles, right-handed first basemen have achieved notable success through exceptional range, quickness, and footwork, as exemplified by Albert Pujols, who earned two Gold Glove Awards at the position during his career.[63] These challenges highlight the subtle but measurable impact of handedness on defensive performance. Coaching strategies to overcome these challenges include mirror drills, where players practice reaches and stretches in front of a mirror to develop muscle memory for opposite-side movements, enhancing reaction time and reducing errors over time.[64]Offensive contributions

Batting expectations

First basemen are archetype power hitters in Major League Baseball, expected to contribute significantly to a team's offensive output through extra-base hits and run production. Historically, since World War II, the position has featured players with a slugging percentage averaging above league norms, often exceeding .450 for top performers, reflecting a premium on raw power over speed or contact skills.[65] This emphasis stems from the position's lower defensive demands compared to up-the-middle infielders, allowing teams to prioritize bats that drive in runs. In the 2025 season, first basemen had an average slugging percentage of .425, contributing to their role as lineup anchors.[66] Due to their typical placement in the third or fourth spot in the batting order, first basemen are positioned for maximum RBI opportunities, benefiting from runners on base ahead of them. This "protection" in the lineup enhances their home run totals, with star players often averaging 25-30 home runs per season, far outpacing the position's overall average of around 15-20. However, the trade-off for this power profile is limited baserunning, as first basemen's slower speed results in fewer stolen bases—typically under 5 per season on average—compared to outfielders or middle infielders. Their on-base plus slugging (OPS) has historically outpaced other infield positions by 35-55 points, underscoring the offensive priority at first base.[65] In 2025, first basemen posted an average OPS of .750, higher than second basemen (.689) or catchers (.694).[67][68] Strategically, first basemen often pull the ball to right field to generate doubles and home runs, a tendency that has drawn defensive shifts since the mid-2010s to counter their power approach. These shifts, which reposition infielders toward the pull side, have become more prevalent post-2015, impacting batting averages on ground balls but reinforcing the position's focus on fly-ball contact for extra bases.[69] Young players transitioning to first base are groomed primarily for power development, with scouting reports emphasizing home run potential and launch angle over high contact rates or speed. This pathway prioritizes slugging efficiency, enabling prospects to project as middle-of-the-order threats early in their careers.Notable power hitters at the position

Lou Gehrig, playing for the New York Yankees from 1923 to 1939, exemplified power hitting at first base with 493 home runs and a .340 batting average over his career.[70] His consistent production, including two American League MVP awards in 1927 and 1936, helped redefine the position as a cornerstone of offensive output during the early 20th century.[70] Gehrig's endurance, marked by a record 2,130 consecutive games played, underscored his reliability as a slugger.[71] Albert Pujols, active from 2001 to 2022 primarily with the St. Louis Cardinals and Los Angeles Angels, amassed 703 home runs, the most by any first baseman in MLB history, surpassing Mark McGwire's previous mark of 583 for primary first basemen at the position.[72] His three National League MVP awards (2005, 2008, 2009) highlighted his sustained excellence, blending power with a .296 career average and 2,218 RBIs.[73] Pujols's longevity and consistency made him a model of enduring offensive dominance at first base.[73] Miguel Cabrera, who began his career in 2003 and continued through 2023 with the Detroit Tigers, reached over 500 home runs (511 total) while maintaining a .306 career batting average.[74] In 2012, he achieved the Triple Crown, leading the American League in batting average (.330), home runs (44), and RBIs (139), a feat that showcased his rare combination of contact and power.[75] Cabrera's two MVP awards (2012, 2013) further cemented his status among elite power hitters.[74] The steroid era (roughly 1994-2004) saw inflated power numbers at first base, exemplified by Mark McGwire's 583 career home runs, many hit during his time with the Oakland Athletics and St. Louis Cardinals, amid widespread performance-enhancing drug use that boosted league-wide home run rates by approximately 50% compared to prior decades.[76][77] In contrast, the analytics era since the mid-2010s has emphasized launch angle and exit velocity, favoring contact-oriented power like Freddie Freeman's 391 home runs through 2025, where he prioritized line drives and doubles (586 career) over raw home run volume.[78][79] This shift reflects broader trends in player development, with first basemen posting lower collective slugging percentages (.425 in 2025) than during the steroid peak.[4]Career transitions and notable players

Shifting to first base as a career move

Players often transition to first base later in their careers due to declining physical attributes such as speed, range, and arm strength, which are more critical for positions like outfield, third base, or catcher.[80] This shift allows veterans to conserve energy while remaining productive contributors, as first base demands less lateral movement and throwing velocity compared to other infield spots.[81] For instance, catchers like Willson Contreras have moved to first base to mitigate the physical toll of their prior role, given their typically below-average speed and arm strength.[80] Such transitions can extend a player's MLB tenure by several years, enabling sluggers to accumulate more hits, home runs, and value into their late 30s or early 40s.[82] The process of shifting to first base typically occurs gradually, often beginning in the minor leagues or as a utility player before becoming a primary role. Players focus on specialized training, such as handling throws with a first baseman's mitt to master scoops and stretches, alongside maintaining offensive power development.[83] This adaptation helps integrate them into the position without abrupt performance drops, as seen with third basemen like Albert Pujols, who transitioned to first base in his mid-30s to preserve his hitting prowess.[84] One key benefit is the position's relative ease in avoiding errors, with first base ranking among the lowest in infield error rates due to fewer high-pressure throws and more routine catches.[85] In 2007, for example, Kevin Youkilis played over 1,000 innings at first base without committing a single error, highlighting the position's forgiving nature for aging defenders. Additionally, first basemen often bat in higher lineup slots, leveraging their offensive skills for more plate appearances and run production.[86] Notable examples include Pete Rose, who debuted as a second baseman and outfielder in 1963 but shifted to first base in 1979 with the Philadelphia Phillies to accommodate Mike Schmidt at third, allowing Rose to pursue records into his 40s.[87] Similarly, Ernie Banks moved from shortstop to first base starting in 1962, extending his Hall of Fame career by focusing on power hitting rather than infield agility.[88] David Ortiz, primarily a designated hitter, occasionally started at first base later in his career, such as in 2015 and during the 2013 World Series, to provide defensive flexibility while preserving his slugging ability.[89] Despite these advantages, the move can reduce a player's team versatility, limiting their ability to fill multiple roles during injury substitutions or lineup adjustments.[90]Hall of Fame inductees

The National Baseball Hall of Fame inducts first basemen based on a combination of exceptional batting performance, such as career averages exceeding .300, defensive prowess evidenced by awards like Gold Gloves, and sustained excellence over at least a decade. Selection emphasizes overall impact on the game, including power hitting, run production, and fielding reliability at the position. Players are classified as first basemen if primarily recognized at the position, though some versatile infielders are included based on significant time played there. As of 2025, 28 players primarily recognized as first basemen have been inducted into the Hall of Fame.[91] Among the early pioneers, Jimmie Foxx, inducted in 1951, stands out for his 534 home runs and three MVP awards, while also earning acclaim as a defensive standout with strong arm and range.[92] Hank Greenberg, enshrined in 1956, captured two MVP honors and a Triple Crown in 1935, amassing 331 home runs despite missing significant time to military service. Willie McCovey, inducted in 1986, slugged 521 home runs over 22 seasons, earning the 1969 MVP and embodying power from the left side.[93] In the modern era, power hitting has increasingly defined the position's Hall of Fame representatives, often prioritizing offensive output over defensive metrics. Frank Thomas, known as "The Big Hurt," joined in 2014 with a .301 batting average and 521 home runs, securing two MVPs primarily as a designated hitter but with significant first-base contributions.[94] Jim Thome, inducted in 2018, hit 612 home runs across a 22-year career, highlighting the trend toward prolific slugging.[95] Recent additions include Todd Helton in 2024, whose .316 average and 369 home runs sparked debate due to the hitter-friendly Coors Field in Colorado, though advanced metrics affirmed his consistency. The 2025 class added Dick Allen, a versatile slugger with 351 home runs and a .292 average, recognized after decades of ballot contention for his impact despite positional shifts.| Inductee | Year | Key Stats | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jimmie Foxx | 1951 | .325 AVG, 534 HR | 3x MVP, Triple Crown (1933), defensive excellence[92] |

| Hank Greenberg | 1956 | .313 AVG, 331 HR | 2x MVP, Triple Crown (1935) |

| Willie McCovey | 1986 | .270 AVG, 521 HR | 1969 MVP, Rookie of the Year (1959)[93] |

| Frank Thomas | 2014 | .301 AVG, 521 HR | 2x MVP, .419 OBP career leader among 1B[94] |

| Jim Thome | 2018 | .276 AVG, 612 HR | 600+ HR club, 5x All-Star as primary 1B[95] |

| Todd Helton | 2024 | .316 AVG, 369 HR | 5x All-Star, Coors Field adjustment in JAWS |

| Dick Allen | 2025 | .292 AVG, 351 HR | 1964 Rookie of the Year, 1972 MVP |