Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

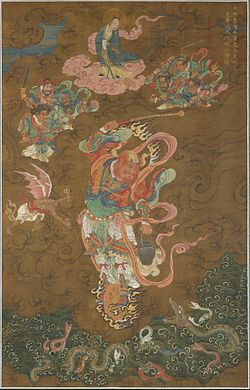

Leigong

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Leigong (Chinese: 雷公; pinyin: léigōng; Wade–Giles: lei2 kung1; lit. 'Lord of Thunder') or Leishen (Chinese: 雷神; pinyin: léishén; lit. 'God of Thunder'), is the god of thunder in Chinese folk religion, Chinese mythology and Taoism. In Taoism, when so ordered by heaven, Leigong punishes both earthly mortals guilty of secret crimes and evil spirits who have used their knowledge of Taoism to harm human beings. He carries a drum and mallet to produce thunder, and a chisel to punish evildoers. Leigong rides a chariot driven by a young boy named A Xiang.

Since Leigong's power is thunder, he has assistants capable of producing other types of heavenly phenomena. Leigong's wife Dianmu is the goddess of lightning, who is said to have used flashing mirrors to send bolts of lightning across the sky.[1] Other companions are Yun Tong ("Cloud Youth"), who whips up clouds, and Yu Shi ("Rain Master") who causes downpours by dipping his sword into a pot. Roaring winds rush forth from a type of goatskin bag manipulated by Fengbo ("Earl of Wind"), who was later transformed into Feng Po Po ("Lady Wind").

Iconography

[edit]

Leigong is depicted as a fearsome creature with claws, bat wings, and a blue face with a bird's beak who wears only a loincloth. Temples dedicated to him are rare, but some people honor him in the hope that he will take revenge on their personal enemies. He used to smile a lot and also wore a friendly face.[2]

Legend

[edit]Leigong began life as a mortal. While on earth, he encountered a peach tree that originated from Heaven during the struggle between the Fox Demon and one of the Celestial Warriors. When Leigong took a bite out of one of its fruit he was transformed into his godly form. He soon received a mace and a hammer that could create thunder.

The Jade Emperor instructed Leigong to only kill bad people. But the sky got really dark whenever he struck people. So sometimes he killed the wrong people since he couldn't find his quarry. Dianmu was one such victim of his blind fury. She lived with her mother in the countryside, where they worked as rice farmers. One day, she dumped a husk of rice into a river because it was too hard for her mother to eat. When Leigong witnessed this action, he became enraged as he thought she was wasting precious food, so when he saw her dumping the husk out he killed her with one of his lightning bolts. The Jade Emperor found out what Leigong had done and was furious that he killed the wrong person again. So the Jade Emperor revived Dianmu and made her into a goddess. He also told Dianmu to marry Leigong as punishment for her murder. He killed her, so it was his fault and his responsibility to take care of her. Dianmu's job is to work with Leigong. She uses mirrors to shine light onto earth so Leigong can see who he hits and makes sure they aren't innocent. This is why lightning comes first.[3][4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ TIAN-MU on Godchecker

- ^ "雷公[雷神] Thunder Lord [Thunder Spirit] – Purple Cloud". 6 March 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ^ Mukherji, Priyadarśī (1999). Chinese and Tibetan Societies Through Folk Literature. Lancers Books. ISBN 9788170950738.

- ^ 歲節的故事 (in Chinese). 知書房出版集團. 2004. ISBN 978-986-7640-16-1.

Notes

[edit]- Storm, Rachel: The Encyclopedia of Eastern Mythology: Legends of the East: Myths and Tales of the Heroes, Gods and Warriors of Ancient Egypt, Arabia, Persia, India, Tibet, China and Japan. ISBN 978-0-7548-0069-9

,_dated_1542.jpg/250px-Master_Thunder_(Lei_Gong),_dated_1542.jpg)

,_dated_1542.jpg)