Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Infinity

View on Wikipedia

Infinity is something which is boundless, limitless, endless, or larger than any natural number. It is denoted by ∞, called the infinity symbol.

From the time of the ancient Greeks, the philosophical nature of infinity has been the subject of many discussions among philosophers. In the 17th century, with the introduction of the infinity symbol[1] and the infinitesimal calculus, mathematicians began to work with infinite series and what some mathematicians (including l'Hôpital and Bernoulli)[2] regarded as infinitely small quantities, but infinity continued to be associated with endless processes. As mathematicians struggled with the foundation of calculus, it remained unclear whether infinity could be considered as a number or magnitude and, if so, how this could be done.[1] At the end of the 19th century, Georg Cantor enlarged the mathematical study of infinity by studying infinite sets and infinite numbers, showing that they can be of various sizes.[1][3] For example, if a line is viewed as the set of all of its points, their infinite number (i.e., the cardinality of the line) is larger than the number of integers.[4] In this usage, infinity is a mathematical concept, and infinite mathematical objects can be studied, manipulated, and used just like any other mathematical object.

The mathematical concept of infinity refines and extends the old philosophical concept, in particular by introducing infinitely many different sizes of infinite sets. Among the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, on which most of modern mathematics can be developed, is the axiom of infinity, which guarantees the existence of infinite sets.[1] The mathematical concept of infinity and the manipulation of infinite sets are widely used in mathematics, even in areas such as combinatorics that may seem to have nothing to do with them. For example, Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem implicitly relies on the existence of Grothendieck universes, very large infinite sets,[5] for solving a long-standing problem that is stated in terms of elementary arithmetic.

In physics and cosmology, it is an open question whether the universe is spatially infinite or not.

History

[edit]Ancient cultures had various ideas about the nature of infinity. The ancient Indians and the Greeks did not define infinity in precise formalism as does modern mathematics, and instead approached infinity as a philosophical concept.

Early Greek

[edit]The earliest recorded idea of infinity in Greece may be that of Anaximander (c. 610 – c. 546 BC) a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher. He used the word apeiron, which means "unbounded", "indefinite", and perhaps can be translated as "infinite".[1][6]

Aristotle (350 BC) distinguished potential infinity from actual infinity, which he regarded as impossible due to the various paradoxes it seemed to produce.[7] It has been argued that, in line with this view, the Hellenistic Greeks had a "horror of the infinite"[8][9] which would, for example, explain why Euclid (c. 300 BC) did not say that there are an infinity of primes but rather "Prime numbers are more than any assigned multitude of prime numbers."[10] It has also been maintained, that, in proving the infinitude of the prime numbers, Euclid "was the first to overcome the horror of the infinite".[11] There is a similar controversy concerning Euclid's parallel postulate, sometimes translated:

If a straight line falling across two [other] straight lines makes internal angles on the same side [of itself whose sum is] less than two right angles, then the two [other] straight lines, being produced to infinity, meet on that side [of the original straight line] that the [sum of the internal angles] is less than two right angles.[12]

Other translators, however, prefer the translation "the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely ...",[13] thus avoiding the implication that Euclid was comfortable with the notion of infinity. Finally, it has been maintained that a reflection on infinity, far from eliciting a "horror of the infinite", underlay all of early Greek philosophy and that Aristotle's "potential infinity" is an aberration from the general trend of this period.[14]

Zeno: Achilles and the tortoise

[edit]Zeno of Elea (c. 495 – c. 430 BC) did not advance any views concerning the infinite. Nevertheless, his paradoxes,[15] especially "Achilles and the Tortoise", were important contributions in that they made clear the inadequacy of popular conceptions. The paradoxes were described by Bertrand Russell as "immeasurably subtle and profound".[16]

Achilles races a tortoise, giving the latter a head start.

- Step #1: Achilles runs to the tortoise's starting point while the tortoise walks forward.

- Step #2: Achilles advances to where the tortoise was at the end of Step #1 while the tortoise goes yet further.

- Step #3: Achilles advances to where the tortoise was at the end of Step #2 while the tortoise goes yet further.

- Step #4: Achilles advances to where the tortoise was at the end of Step #3 while the tortoise goes yet further.

Etc.

Apparently, Achilles never overtakes the tortoise, since however many steps he completes, the tortoise remains ahead of him.

Zeno was not attempting to make a point about infinity. As a member of the Eleatics school which regarded motion as an illusion, he saw it as a mistake to suppose that Achilles could run at all. Subsequent thinkers, finding this solution unacceptable, struggled for over two millennia to find other weaknesses in the argument.

Finally, in 1821, Augustin-Louis Cauchy provided both a satisfactory definition of a limit and a proof that, for 0 < x < 1,[17]

Suppose that Achilles is running at 10 meters per second, the tortoise is walking at 0.1 meters per second, and the latter has a 100-meter head start. The duration of the chase fits Cauchy's pattern with a = 10 seconds and x = 0.01. Achilles does overtake the tortoise; it takes him

Early Indian

[edit]The Jain mathematical text Surya Prajnapti (c. 4th–3rd century BCE) classifies all numbers into three sets: enumerable, innumerable, and infinite. Each of these was further subdivided into three orders:[18]

- Enumerable: lowest, intermediate, and highest

- Innumerable: nearly innumerable, truly innumerable, and innumerably innumerable

- Infinite: nearly infinite, truly infinite, infinitely infinite

17th century

[edit]In the 17th century, European mathematicians started using infinite numbers and infinite expressions in a systematic fashion. In 1655, John Wallis first used the notation for such a number in his De sectionibus conicis,[19] and exploited it in area calculations by dividing the region into infinitesimal strips of width on the order of [20] But in Arithmetica infinitorum (1656),[21] he indicates infinite series, infinite products and infinite continued fractions by writing down a few terms or factors and then appending "&c.", as in "1, 6, 12, 18, 24, &c."[22]

In 1699, Isaac Newton wrote about equations with an infinite number of terms in his work De analysi per aequationes numero terminorum infinitas.[23]

Symbol

[edit]The infinity symbol (sometimes called the lemniscate) is a mathematical symbol representing the concept of infinity. The symbol is encoded in Unicode at U+221E ∞ INFINITY (∞)[24] and in LaTeX as \infty.[25]

It was introduced in 1655 by John Wallis,[26][27] and since its introduction, it has also been used outside mathematics in modern mysticism[28] and literary symbology.[29]

Calculus

[edit]Gottfried Leibniz, one of the co-inventors of infinitesimal calculus, speculated widely about infinite numbers and their use in mathematics. To Leibniz, both infinitesimals and infinite quantities were ideal entities, not of the same nature as appreciable quantities, but enjoying the same properties in accordance with the Law of continuity.[30][2]

Real analysis

[edit]In real analysis, the symbol , called "infinity", is used to denote an unbounded limit.[31] It is not a real number itself. The notation means that increases without bound, and means that decreases without bound. For example, if for every , then[32]

- means that does not bound a finite area from to

- means that the area under is infinite.

- means that the total area under is finite, and is equal to

Infinity can also be used to describe infinite series, as follows:

- means that the sum of the infinite series converges to some real value

- means that the sum of the infinite series properly diverges to infinity, in the sense that the partial sums increase without bound.[33]

In addition to defining a limit, infinity can be also used as a value in the extended real number system. Points labeled and can be added to the topological space of the real numbers, producing the two-point compactification of the real numbers. Adding algebraic properties to this gives us the extended real numbers.[34] We can also treat and as the same, leading to the one-point compactification of the real numbers, which is the real projective line.[35] Projective geometry also refers to a line at infinity in plane geometry, a plane at infinity in three-dimensional space, and a hyperplane at infinity for general dimensions, each consisting of points at infinity.[36]

Complex analysis

[edit]

In complex analysis the symbol , called "infinity", denotes an unsigned infinite limit. The expression means that the magnitude of grows beyond any assigned value. A point labeled can be added to the complex plane as a topological space giving the one-point compactification of the complex plane. When this is done, the resulting space is a one-dimensional complex manifold, or Riemann surface, called the extended complex plane or the Riemann sphere.[37] Arithmetic operations similar to those given above for the extended real numbers can also be defined, though there is no distinction in the signs (which leads to the one exception that infinity cannot be added to itself). On the other hand, this kind of infinity enables division by zero, namely for any nonzero complex number . In this context, it is often useful to consider meromorphic functions as maps into the Riemann sphere taking the value of at the poles. The domain of a complex-valued function may be extended to include the point at infinity as well. One important example of such functions is the group of Möbius transformations (see Möbius transformation § Overview).

Nonstandard analysis

[edit]

The original formulation of infinitesimal calculus by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibniz used infinitesimal quantities. In the second half of the 20th century, it was shown that this treatment could be put on a rigorous footing through various logical systems, including smooth infinitesimal analysis and nonstandard analysis. In the latter, infinitesimals are invertible, and their inverses are infinite numbers. The infinities in this sense are part of a hyperreal field; there is no equivalence between them as with the Cantorian transfinites. For example, if H is an infinite number in this sense, then H + H = 2H and H + 1 are distinct infinite numbers. This approach to non-standard calculus is fully developed in Keisler (1986).

Set theory

[edit]

A different form of "infinity" is the ordinal and cardinal infinities of set theory—a system of transfinite numbers first developed by Georg Cantor. In this system, the first transfinite cardinal is aleph-null (ℵ0), the cardinality of the set of natural numbers. This modern mathematical conception of the quantitative infinite developed in the late 19th century from works by Cantor, Gottlob Frege, Richard Dedekind and others—using the idea of collections or sets.[1]

Dedekind's approach was essentially to adopt the idea of one-to-one correspondence as a standard for comparing the size of sets, and to reject the view of Galileo (derived from Euclid) that the whole cannot be the same size as the part. (However, see Galileo's paradox where Galileo concludes that positive integers cannot be compared to the subset of positive square integers since both are infinite sets.) An infinite set can simply be defined as one having the same size as at least one of its proper parts; this notion of infinity is called Dedekind infinite. The diagram to the right gives an example: viewing lines as infinite sets of points, the left half of the lower blue line can be mapped in a one-to-one manner (green correspondences) to the higher blue line, and, in turn, to the whole lower blue line (red correspondences); therefore the whole lower blue line and its left half have the same cardinality, i.e. "size".[38]

Cantor defined two kinds of infinite numbers: ordinal numbers and cardinal numbers. Ordinal numbers characterize well-ordered sets, or counting carried on to any stopping point, including points after an infinite number have already been counted. Generalizing finite and (ordinary) infinite sequences which are maps from the positive integers leads to mappings from ordinal numbers to transfinite sequences. Cardinal numbers define the size of sets, meaning how many members they contain, and can be standardized by choosing the first ordinal number of a certain size to represent the cardinal number of that size. The smallest ordinal infinity is that of the positive integers, and any set which has the cardinality of the integers is countably infinite. If a set is too large to be put in one-to-one correspondence with the positive integers, it is called uncountable. Cantor's views prevailed and modern mathematics accepts actual infinity as part of a consistent and coherent theory.[39] Certain extended number systems, such as the hyperreal numbers, incorporate the ordinary (finite) numbers and infinite numbers of different sizes.[40]

Cardinality of the continuum

[edit]One of Cantor's most important results was that the cardinality of the continuum is greater than that of the natural numbers ; that is, there are more real numbers R than natural numbers N. Namely, Cantor showed that .[41]

The continuum hypothesis states that there is no cardinal number between the cardinality of the reals and the cardinality of the natural numbers, that is, .

This hypothesis cannot be proved or disproved within the widely accepted Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, even assuming the Axiom of Choice.[42]

Cardinal arithmetic can be used to show not only that the number of points in a real number line is equal to the number of points in any segment of that line, but also that this is equal to the number of points on a plane and, indeed, in any finite-dimensional space.[43]

The first of these results is apparent by considering, for instance, the tangent function, which provides a one-to-one correspondence between the interval (−π/2, π/2) and R.

The second result was proved by Cantor in 1878, but only became intuitively apparent in 1890, when Giuseppe Peano introduced the space-filling curves, curved lines that twist and turn enough to fill the whole of any square, or cube, or hypercube, or finite-dimensional space. These curves can be used to define a one-to-one correspondence between the points on one side of a square and the points in the square.[44]

Geometry

[edit]Until the end of the 19th century, infinity was rarely discussed in geometry, except in the context of processes that could be continued without any limit. For example, a line was what is now called a line segment, with the proviso that one can extend it as far as one wants; but extending it infinitely was out of the question. Similarly, a line was usually not considered to be composed of infinitely many points but was a location where a point may be placed. Even if there are infinitely many possible positions, only a finite number of points could be placed on a line. A witness of this is the expression "the locus of a point that satisfies some property" (singular), where modern mathematicians would generally say "the set of the points that have the property" (plural).

One of the rare exceptions of a mathematical concept involving actual infinity was projective geometry, where points at infinity are added to the Euclidean space for modeling the perspective effect that shows parallel lines intersecting "at infinity". Mathematically, points at infinity have the advantage of allowing one to not consider some special cases. For example, in a projective plane, two distinct lines intersect in exactly one point, whereas without points at infinity, there are no intersection points for parallel lines. So, parallel and non-parallel lines must be studied separately in classical geometry, while they need not be distinguished in projective geometry.

Before the use of set theory for the foundation of mathematics, points and lines were viewed as distinct entities, and a point could be located on a line. With the universal use of set theory in mathematics, the point of view has dramatically changed: a line is now considered as the set of its points, and one says that a point belongs to a line instead of is located on a line (however, the latter phrase is still used).

In particular, in modern mathematics, lines are infinite sets.

Infinite dimension

[edit]The vector spaces that occur in classical geometry have always a finite dimension, generally two or three. However, this is not implied by the abstract definition of a vector space, and vector spaces of infinite dimension can be considered. This is typically the case in functional analysis where function spaces are generally vector spaces of infinite dimension.

In topology, some constructions can generate topological spaces of infinite dimension. In particular, this is the case of iterated loop spaces.

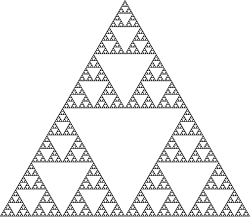

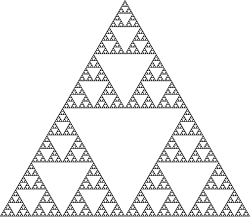

Fractals

[edit]The structure of a fractal object is reiterated in its magnifications. Fractals can be magnified indefinitely without losing their structure and becoming "smooth"; they have infinite perimeters and can have infinite or finite areas. One such fractal curve with an infinite perimeter and finite area is the Koch snowflake.[45]

Finitism

[edit]Leopold Kronecker was skeptical of the notion of infinity and how his fellow mathematicians were using it in the 1870s and 1880s. This skepticism was developed in the philosophy of mathematics called finitism, an extreme form of mathematical philosophy in the general philosophical and mathematical schools of constructivism and intuitionism.[46]

Logic

[edit]In logic, an infinite regress argument is "a distinctively philosophical kind of argument purporting to show that a thesis is defective because it generates an infinite series when either (form A) no such series exists or (form B) were it to exist, the thesis would lack the role (e.g., of justification) that it is supposed to play."[47]

In first-order logic, both the compactness theorem and Löwenheim–Skolem theorems are used to construct non-standard models with certain infinite properties.

Applications

[edit]Physics

[edit]In physics, approximations of real numbers are used for continuous measurements and natural numbers are used for discrete measurements (i.e., counting). Concepts of infinite things such as an infinite plane wave exist, but there are no experimental means to generate them.[48]

Cosmology

[edit]The first published proposal that the universe is infinite came from Thomas Digges in 1576.[49] Eight years later, in 1584, the Italian philosopher and astronomer Giordano Bruno proposed an unbounded universe in On the Infinite Universe and Worlds: "Innumerable suns exist; innumerable earths revolve around these suns in a manner similar to the way the seven planets revolve around our sun. Living beings inhabit these worlds."[50]

Cosmologists have long sought to discover whether infinity exists in our physical universe: Are there an infinite number of stars? Does the universe have infinite volume? Does space "go on forever"? This is still an open question of cosmology. The question of being infinite is logically separate from the question of having boundaries. The two-dimensional surface of the Earth, for example, is finite, yet has no edge. By travelling in a straight line with respect to the Earth's curvature, one will eventually return to the exact spot one started from. The universe, at least in principle, might have a similar topology. If so, one might eventually return to one's starting point after travelling in a straight line through the universe for long enough.[51]

The curvature of the universe can be measured through multipole moments in the spectrum of the cosmic background radiation. To date, analysis of the radiation patterns recorded by the WMAP spacecraft hints that the universe has a flat topology. This would be consistent with an infinite physical universe.[52][53][54]

However, the universe could be finite, even if its curvature is flat. An easy way to understand this is to consider two-dimensional examples, such as video games where items that leave one edge of the screen reappear on the other. The topology of such games is toroidal and the geometry is flat. Many possible bounded, flat possibilities also exist for three-dimensional space.[55]

The concept of infinity also extends to the multiverse hypothesis, which, when explained by astrophysicists such as Michio Kaku, posits that there are an infinite number and variety of universes.[56] Also, cyclic models posit an infinite amount of Big Bangs, resulting in an infinite variety of universes after each Big Bang event in an infinite cycle.[57]

Computing

[edit]The IEEE floating-point standard (IEEE 754) specifies a positive and a negative infinity value (and also indefinite values). These are defined as the result of arithmetic overflow, division by zero, and other exceptional operations.[58]

Some programming languages, such as Java[59] and J,[60] allow the programmer an explicit access to the positive and negative infinity values as language constants. These can be used as greatest and least elements, as they compare (respectively) greater than or less than all other values. They have uses as sentinel values in algorithms involving sorting, searching, or windowing.[citation needed]

In languages that do not have greatest and least elements but do allow overloading of relational operators, it is possible for a programmer to create the greatest and least elements. In languages that do not provide explicit access to such values from the initial state of the program but do implement the floating-point data type, the infinity values may still be accessible and usable as the result of certain operations.[citation needed]

In programming, an infinite loop is a loop whose exit condition is never satisfied, thus executing indefinitely.

Arts, games, and cognitive sciences

[edit]Perspective artwork uses the concept of vanishing points, roughly corresponding to mathematical points at infinity, located at an infinite distance from the observer. This allows artists to create paintings that realistically render space, distances, and forms.[61] Artist M.C. Escher is specifically known for employing the concept of infinity in his work in this and other ways.[62]

Variations of chess played on an unbounded board are called infinite chess.[63][64]

Cognitive scientist George Lakoff considers the concept of infinity in mathematics and the sciences as a metaphor. This perspective is based on the basic metaphor of infinity (BMI), defined as the ever-increasing sequence <1, 2, 3, …>.[65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Allen, Donald (2003). "The History of Infinity" (PDF). Texas A&M Mathematics. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 1, 2020. Retrieved Nov 15, 2019.

- ^ a b Jesseph, Douglas Michael (1998-05-01). "Leibniz on the Foundations of the Calculus: The Question of the Reality of Infinitesimal Magnitudes". Perspectives on Science. 6 (1&2): 6–40. doi:10.1162/posc_a_00543. ISSN 1063-6145. OCLC 42413222. S2CID 118227996. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2019 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Gowers, Timothy; Barrow-Green, June (2008). The Princeton companion to mathematics. Imre Leader, Princeton University. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3039-8. OCLC 659590835.

- ^ Maddox 2002, pp. 113–117

- ^ McLarty, Colin (15 January 2014) [September 2010]. "What Does it Take to Prove Fermat's Last Theorem? Grothendieck and the Logic of Number Theory". The Bulletin of Symbolic Logic. 16 (3): 359–377. doi:10.2178/bsl/1286284558. S2CID 13475845 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Wallace 2004, p. 44

- ^ Aristotle. Physics. Translated by Hardie, R. P.; Gaye, R. K. The Internet Classics Archive. Book 3, Chapters 5–8.

- ^ Goodman, Nicolas D. (1981). "Reflections on Bishop's philosophy of mathematics". In Richman, F. (ed.). Constructive Mathematics. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. Vol. 873. Springer. pp. 135–145. doi:10.1007/BFb0090732. ISBN 978-3-540-10850-4.

- ^ Maor, p. 3

- ^ Sarton, George (March 1928). "The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements. Thomas L. Heath, Heiberg". Isis. 10 (1): 60–62. doi:10.1086/346308. ISSN 0021-1753 – via The University of Chicago Press Journals.

- ^ Hutten, Ernest Hirschlaff (1962). The origins of science; an inquiry into the foundations of Western thought. Internet Archive. London, Allen and Unwin. pp. 1–241. ISBN 978-0-04-946007-2. Retrieved 2020-01-09.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Euclid (2008) [c. 300 BC]. Euclid's Elements of Geometry (PDF). Translated by Fitzpatrick, Richard. Lulu.com. p. 6 (Book I, Postulate 5). ISBN 978-0-6151-7984-1.

- ^ Heath, Sir Thomas Little; Heiberg, Johan Ludvig (1908). The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements. Vol. v. 1. The University Press. p. 212.

- ^ Drozdek, Adam (2008). In the Beginning Was the Apeiron: Infinity in Greek Philosophy. Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-09258-6.

- ^ "Zeno's Paradoxes". Stanford University. October 15, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Russell 1996, p. 347

- ^ Cauchy, Augustin-Louis (1821). Cours d'Analyse de l'École Royale Polytechnique. Libraires du Roi & de la Bibliothèque du Roi. p. 124. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Ian Stewart (2017). Infinity: a Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-19-875523-4. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (2007). A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 1. Cosimo, Inc. p. 214. ISBN 9781602066854.

- ^ Cajori 1993, Sec. 421, Vol. II, p. 44

- ^ "Arithmetica Infinitorum".

- ^ Cajori 1993, Sec. 435, Vol. II, p. 58

- ^ Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (2005). Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics 1640-1940. Elsevier. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-08-045744-4. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Extract of p. 62

- ^ AG, Compart. "Unicode Character "∞" (U+221E)". Compart.com. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ "List of LaTeX mathematical symbols - OeisWiki". oeis.org. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ Scott, Joseph Frederick (1981), The mathematical work of John Wallis, D.D., F.R.S., (1616–1703) (2 ed.), American Mathematical Society, p. 24, ISBN 978-0-8284-0314-6, archived from the original on 2016-05-09

- ^ Martin-Löf, Per (1990), "Mathematics of infinity", COLOG-88 (Tallinn, 1988), Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 417, Berlin: Springer, pp. 146–197, doi:10.1007/3-540-52335-9_54, ISBN 978-3-540-52335-2, MR 1064143

- ^ O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger (1986), Dreams, Illusion, and Other Realities, University of Chicago Press, p. 243, ISBN 978-0-226-61855-5, archived from the original on 2016-06-29

- ^ Toker, Leona (1989), Nabokov: The Mystery of Literary Structures, Cornell University Press, p. 159, ISBN 978-0-8014-2211-9, archived from the original on 2016-05-09

- ^ Bell, John Lane. "Continuity and Infinitesimals". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Taylor 1955, p. 63

- ^ These uses of infinity for integrals and series can be found in any standard calculus text, such as, Swokowski 1983, pp. 468–510

- ^ "Properly Divergent Sequences - Mathonline". mathonline.wikidot.com. Retrieved 2019-11-15.

- ^ Aliprantis, Charalambos D.; Burkinshaw, Owen (1998), Principles of Real Analysis (3rd ed.), San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc., p. 29, ISBN 978-0-12-050257-8, MR 1669668, archived from the original on 2015-05-15

- ^ Gemignani 1990, p. 177

- ^ Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998), Projective Geometry / from foundations to applications, Cambridge University Press, p. 27, ISBN 978-0-521-48364-3

- ^ Rao, Murali; Stetkær, Henrik (1991). Complex Analysis: An Invitation : a Concise Introduction to Complex Function Theory. World Scientific. p. 113. ISBN 9789810203757.

- ^ Eric Schechter (2005). Classical and Nonclassical Logics: An Introduction to the Mathematics of Propositions (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-691-12279-3. Extract of page 118

- ^ A.W. Moore (2012). The Infinite (2nd, revised ed.). Routledge. p. xiv. ISBN 978-1-134-91213-1. Extract of page xiv

- ^ Rudolf V Rucker (2019). Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-691-19125-6. Extract of page 85

- ^ Dauben, Joseph (1993). "Georg Cantor and the Battle for Transfinite Set Theory" (PDF). 9th ACMS Conference Proceedings: 4.

- ^ Cohen 1963, p. 1143

- ^ Felix Hausdorff (2021). Set Theory. American Mathematical Soc. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4704-6494-3. Extract of page 44

- ^ Sagan 1994, pp. 10–12

- ^ Michael Frame; Benoit Mandelbrot (2002). Fractals, Graphics, and Mathematics Education (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-88385-169-2. Extract of page 36

- ^ Kline 1972, pp. 1197–1198

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Second Edition, p. 429

- ^ Doric Lenses Archived 2013-01-24 at the Wayback Machine – Application Note – Axicons – 2. Intensity Distribution. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ John Gribbin (2009), In Search of the Multiverse: Parallel Worlds, Hidden Dimensions, and the Ultimate Quest for the Frontiers of Reality, ISBN 978-0-470-61352-8. p. 88

- ^ Brake, Mark (2013). Alien Life Imagined: Communicating the Science and Culture of Astrobiology (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-521-49129-7.

- ^ Koupelis, Theo; Kuhn, Karl F. (2007). In Quest of the Universe (illustrated ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 553. ISBN 978-0-7637-4387-1. Extract of p. 553

- ^ "Will the Universe expand forever?". NASA. 24 January 2014. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ "Our universe is Flat". FermiLab/SLAC. 7 April 2015. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015.

- ^ Marcus Y. Yoo (2011). "Unexpected connections". Engineering & Science. LXXIV1: 30.

- ^ Weeks, Jeffrey (2001). The Shape of Space. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8247-0709-5.

- ^ Kaku, M. (2006). Parallel worlds. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- ^ McKee, Maggie (25 September 2014). "Ingenious: Paul J. Steinhardt – The Princeton physicist on what's wrong with inflation theory and his view of the Big Bang". Nautilus. No. 17. NautilusThink Inc. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- ^ "Infinity and NaN (The GNU C Library)". www.gnu.org. Retrieved 2021-03-15.

- ^ Gosling, James; et al. (27 July 2012). "4.2.3.". The Java Language Specification (Java SE 7 ed.). California: Oracle America, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Stokes, Roger (July 2012). "19.2.1". Learning J. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Morris Kline (1985). Mathematics for the Nonmathematician (illustrated, unabridged, reprinted ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-486-24823-3. Extract of page 229, Section 10-7

- ^ Schattschneider, Doris (2010). "The Mathematical Side of M. C. Escher" (PDF). Notices of the AMS. 57 (6): 706–718.

- ^ Infinite chess at the Chess Variant Pages Archived 2017-04-02 at the Wayback Machine An infinite chess scheme.

- ^ "Infinite Chess, PBS Infinite Series" Archived 2017-04-07 at the Wayback Machine PBS Infinite Series, with academic sources by J. Hamkins (infinite chess: Evans, C.D.A; Joel David Hamkins (2013). "Transfinite game values in infinite chess". arXiv:1302.4377 [math.LO]. and Evans, C.D.A; Joel David Hamkins; Norman Lewis Perlmutter (2015). "A position in infinite chess with game value $ω^4$". arXiv:1510.08155 [math.LO].).

- ^ Elglaly, Yasmine Nader; Quek, Francis. "Review of "Where Mathematics comes from: How the Embodied Mind Brings Mathematics Into Being" By George Lakoff and Rafael E. Nunez" (PDF). CHI 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-26. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cajori, Florian (1993) [1928 & 1929], A History of Mathematical Notations (Two Volumes Bound as One), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-67766-8

- Gemignani, Michael C. (1990), Elementary Topology (2nd ed.), Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-66522-1

- Keisler, H. Jerome (1986), Elementary Calculus: An Approach Using Infinitesimals (2nd ed.)

- Maddox, Randall B. (2002), Mathematical Thinking and Writing: A Transition to Abstract Mathematics, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-464976-7

- Kline, Morris (1972), Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1197–1198, ISBN 978-0-19-506135-2

- Russell, Bertrand (1996) [1903], The Principles of Mathematics, New York: Norton, ISBN 978-0-393-31404-5, OCLC 247299160

- Sagan, Hans (1994), Space-Filling Curves, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4612-0871-6

- Swokowski, Earl W. (1983), Calculus with Analytic Geometry (Alternate ed.), Prindle, Weber & Schmidt, ISBN 978-0-87150-341-1

- Taylor, Angus E. (1955), Advanced Calculus, Blaisdell Publishing Company

- Wallace, David Foster (2004), Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity, Norton, W.W. & Company, Inc., ISBN 978-0-393-32629-1

Sources

[edit]- Aczel, Amir D. (2001). The Mystery of the Aleph: Mathematics, the Kabbalah, and the Search for Infinity. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 978-0-7434-2299-4.

- D.P. Agrawal (2000). Ancient Jaina Mathematics: an Introduction, Infinity Foundation.

- Bell, J.L.: Continuity and infinitesimals. Stanford Encyclopedia of philosophy. Revised 2009.

- Cohen, Paul (1963), "The Independence of the Continuum Hypothesis", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 50 (6): 1143–1148, Bibcode:1963PNAS...50.1143C, doi:10.1073/pnas.50.6.1143, PMC 221287, PMID 16578557.

- Jain, L.C. (1982). Exact Sciences from Jaina Sources.

- Jain, L.C. (1973). "Set theory in the Jaina school of mathematics", Indian Journal of History of Science.

- Joseph, George G. (2000). The Crest of the Peacock: Non-European Roots of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-027778-4.

- H. Jerome Keisler: Elementary Calculus: An Approach Using Infinitesimals. First edition 1976; 2nd edition 1986. This book is now out of print. The publisher has reverted the copyright to the author, who has made available the 2nd edition in .pdf format available for downloading at http://www.math.wisc.edu/~keisler/calc.html

- Eli Maor (1991). To Infinity and Beyond. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02511-7.

- O'Connor, John J. and Edmund F. Robertson (1998). 'Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor' Archived 2006-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- O'Connor, John J. and Edmund F. Robertson (2000). 'Jaina mathematics' Archived 2008-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Pearce, Ian. (2002). 'Jainism', MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Rucker, Rudy (1995). Infinity and the Mind: The Science and Philosophy of the Infinite. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00172-2.

- Singh, Navjyoti (1988). "Jaina Theory of Actual Infinity and Transfinite Numbers". Journal of the Asiatic Society. 30.

External links

[edit]- Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). "The Infinite". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658.

- Infinity on In Our Time at the BBC

- A Crash Course in the Mathematics of Infinite Sets Archived 2010-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, by Peter Suber. From the St. John's Review, XLIV, 2 (1998) 1–59. The stand-alone appendix to Infinite Reflections, below. A concise introduction to Cantor's mathematics of infinite sets.

- Infinite Reflections Archived 2009-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, by Peter Suber. How Cantor's mathematics of the infinite solves a handful of ancient philosophical problems of the infinite. From the St. John's Review, XLIV, 2 (1998) 1–59.

- Grime, James. "Infinity is bigger than you think". Numberphile. Brady Haran. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Hotel Infinity

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson (1998). 'Georg Ferdinand Ludwig Philipp Cantor' Archived 2006-09-16 at the Wayback Machine, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson (2000). 'Jaina mathematics' Archived 2008-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- Ian Pearce (2002). 'Jainism', MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- The Mystery Of The Aleph: Mathematics, the Kabbalah, and the Search for Infinity

- Dictionary of the Infinite (compilation of articles about infinity in physics, mathematics, and philosophy)

Infinity

View on GrokipediaHistorical Development

Ancient Greek and Indian Concepts

In ancient Greek philosophy, the concept of infinity emerged through cosmological and metaphysical speculations that challenged finite boundaries in the natural world. Anaximander of Miletus (c. 610–546 BCE), a pre-Socratic thinker, proposed the apeiron—the boundless or unlimited—as the primordial substance underlying all existence. This indefinite, eternal, and infinite entity, distinct from specific elements like water or air, served as the source from which opposites such as hot and cold arose, and to which all things returned through a process governed by cosmic justice.[6][7] The apeiron was envisioned as spatially and temporally infinite, ensuring perpetual generation and decay without exhaustion, marking an early abstraction away from mythological origins toward a naturalistic infinite substrate.[7] Zeno of Elea (c. 490–430 BCE), a disciple of Parmenides, further explored infinity through paradoxes that highlighted the logical difficulties of motion, plurality, and divisibility, defending the Eleatic view of reality as a singular, unchanging whole. In the dichotomy paradox, Zeno argued that to traverse any distance, one must first cover half of it, then half of the remainder, and so on, resulting in an infinite series of tasks that cannot be completed in finite time, thus rendering motion impossible.[8] The Achilles and the tortoise paradox extended this idea: even a swift runner like Achilles, given a head start to a tortoise, must endlessly approach but never reach it, as he covers infinite diminishing intervals before overtaking.[8] Similarly, the arrow paradox posited that at any instant, an arrow in flight occupies a single position and is thus at rest, implying that motion, composed of such instants, cannot exist—a challenge rooted in the infinite divisibility of space and time.[8] These arguments, preserved in fragments by later writers like Aristotle, underscored the paradoxes of assuming infinity in the physical world without formal resolution. In ancient Indian thought, particularly in Jainism from the 6th century BCE, infinity (ananta) was integral to cosmology and metaphysics, describing an eternal, uncreated universe encompassing boundless categories of existence. Jain texts, such as those attributed to Mahavira (c. 599–527 BCE), categorized reality into infinite space (akasa), which is all-pervading and composed of infinite space-points; infinite time (kala), structured in endless cycles without beginning or end; and infinite souls (jiva), each possessing potential infinite attributes like knowledge, perception, bliss, and energy (ananta-catushtaya).[9][10] This framework viewed the cosmos as a finite inhabited region within an infinite expanse, emphasizing non-absolutism (anekantavada) where infinity manifests in multifaceted, inexhaustible forms across matter, motion, and rest.[11] Early Vedic texts, dating from around 1500–1200 BCE, incorporated infinity through cyclical cosmologies that portrayed the universe as undergoing perpetual cycles of creation, preservation, and dissolution. The Rigveda describes cosmic processes emerging from an indeterminate, infinite source, with time structured in vast, repeating yugas and kalpas that extend boundlessly, reflecting an eternal rhythm without absolute origin or termination.[12] This infinite recursion, personified in deities like Vishnu as the preserver across endless epochs, integrated infinity into both material and spiritual realms, influencing later Puranic elaborations on boundless multiverses.[12]Medieval to 17th-Century European Views

In medieval Europe, the concept of infinity was largely shaped by Aristotle's distinction between potential and actual infinity, which had been transmitted through Islamic philosophy and early scholasticism. Aristotle posited potential infinity as an ongoing process that could continue indefinitely without completion, such as the division of a line segment or the counting of numbers, but he rejected actual infinity as an existing completed totality, arguing it would lead to contradictions and undermine the finite nature of the physical world.[5] This framework influenced medieval thinkers by providing a philosophical basis for reconciling infinity with Christian theology, where infinity was often reserved for divine attributes while creation remained finite and actual infinities were deemed impossible in the material realm.[13] Theological discussions further developed these ideas, particularly through the works of Thomas Aquinas and Islamic philosophers like Al-Ghazali, whose writings impacted European scholarship via translations. Aquinas, drawing on Aristotle, affirmed God's infinite nature as perfect and unbounded in essence, power, and knowledge, but emphasized that creation is finite to avoid paradoxes; for instance, he argued that an infinite series of causes would imply no first cause, thus necessitating a finite universe originating from an infinite God.[14] Similarly, Al-Ghazali critiqued Aristotelian eternalism by highlighting the incoherence of an actual infinite past, asserting that the universe's finite creation by an infinite God resolves temporal paradoxes, a view that resonated in medieval debates on divine infinity versus created finitude.[5] A key figure bridging theology and early mathematics was Nicholas of Cusa, who in his 1440 work De Docta Ignorantia introduced the principle of "learned ignorance," positing that human reason cannot fully comprehend infinite divine attributes like God's oneness and eternity, yet through this awareness, one approaches truth by recognizing the infinite as the coincidence of opposites—maximum and minimum—in God's nature.[15] By the 17th century, European views shifted toward mathematical explorations of infinity, exemplified by Galileo's paradox and the symbolization of the infinite. In Two New Sciences (1638), Galileo observed that the natural numbers and their perfect squares (1, 4, 9, 16, ...) can be put into one-to-one correspondence, implying that an infinite whole is neither larger nor smaller than a proper subset of itself, which he described as a "property of infinity" defying intuitive proportions.[16] This paradox highlighted tensions between Aristotelian potential infinity and emerging ideas of actual infinities in mathematics. Concurrently, John Wallis introduced the lemniscate symbol ∞ in his 1655 treatise De sectionibus conicis to denote indefinitely large quantities in the study of conic sections and series, marking a pivotal step in formalizing infinity's notation for analytical purposes.[17]19th-Century Paradoxes and Resolutions

In the mid-19th century, Bernhard Bolzano advanced the study of infinity through his posthumously published Paradoxien des Unendlichen (1851), where he systematically analyzed properties of infinite collections and highlighted their paradoxical behaviors relative to finite sets. Bolzano demonstrated that an infinite set can be placed in one-to-one correspondence with one of its proper subsets—a defining characteristic that distinguishes infinity from finitude—and applied this to resolve apparent contradictions, such as the equinumerosity of the natural numbers and the subset of their squares.[18] His work prefigured modern set theory by emphasizing the consistency of such correspondences without relying on actual infinities, instead treating them as completed wholes in a logical framework.[19] Building on these ideas, Georg Cantor revolutionized mathematics in the 1870s by introducing the concept of distinct infinite cardinalities, proving that not all infinities are equivalent in size. In his 1874 paper "Über eine Eigenschaft des Inbegriffes aller reellen algebraischen Zahlen," Cantor showed that the set of real algebraic numbers is countably infinite by enumerating polynomials with rational coefficients and their roots, and proved that the real numbers are uncountably infinite using nested intervals.[20] This established the existence of infinities larger than the countable infinity of the naturals, challenging intuitive notions of size and laying groundwork for transfinite arithmetic. Cantor's later 1891 diagonal argument extended this to all real numbers: assuming a countable enumeration of reals as infinite sequences of digits, he constructed a new real differing from each listed one in at least one diagonal position, proving by contradiction that no such complete enumeration exists.[21] Concurrently, Richard Dedekind addressed foundational issues involving infinity in his 1872 essay Stetigkeit und irrationale Zahlen, where he defined real numbers via "cuts" that partition the rationals into two nonempty sets with all elements of one less than the other, without a greatest or least bounding rational. This construction implicitly relies on infinite sets, as each cut represents an infinite division of the rationals, providing a rigorous basis for the continuum and resolving paradoxes of continuity without infinitesimals.[22] Dedekind's approach complemented Cantor's by formalizing the uncountable nature of the reals through set-theoretic means, emphasizing arithmetic completeness over geometric intuition.[23] These developments illuminated the paradoxes of infinity, such as the counterintuitive equipotence of infinite sets with proper subsets, which Bolzano and Cantor both explored. A vivid illustration of countable infinity's peculiarities is Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel, where a fully occupied hotel with countably infinite rooms can accommodate additional guests (even countably infinitely many) by systematically shifting occupants to higher-numbered rooms, freeing up space without eviction. Though articulated by David Hilbert in the early 20th century, this thought experiment elucidates 19th-century insights into bijections preserving cardinality in infinite domains.[24]Symbolic and Conceptual Foundations

Notation and Symbols for Infinity

The lemniscate symbol ∞, resembling a sideways figure eight, was introduced by English mathematician John Wallis in 1655 in his work De sectionibus conicis. There, it denoted infinite quantities in the study of conic sections and infinite series, marking the first standardized mathematical representation of infinity.[25] The term "lemniscate" derives from the Latin lemniscus, meaning ribbon, reflecting the symbol's looped form.[25] Leonhard Euler adopted the ∞ symbol in the mid-18th century, employing it extensively in his treatises on analysis and infinite series, such as in Introductio in analysin infinitorum (1748), where it signified unbounded growth or endless summation.[26] Euler's prolific use helped solidify its place in calculus notation, transitioning it from geometric contexts to broader analytical applications.[26] In set theory, alternative notations emerged for distinguishing sizes of infinity. Georg Cantor introduced the aleph symbols, beginning with ℵ₀ (aleph-null) in 1895, to represent the cardinalities of infinite sets, where ℵ₀ denotes the smallest infinite cardinality, that of the natural numbers. This Hebrew letter-based notation, chosen by Cantor for its association with transcendence, allowed precise enumeration of transfinite numbers beyond the lemniscate's general usage. The ∞ symbol plays a key role in real analysis through the extended real line, which appends +∞ and −∞ to the real numbers ℝ, forming the set \overline{\mathbb{R}}. This construction facilitates handling divergent limits and improper integrals without undefined expressions.[27] For instance, limits approaching infinity are expressed as , a notation formalized in 19th-century texts to describe asymptotic behavior.[28] In integration, ∞ denotes unbounded domains, as in the improper integral , which evaluates the area under a curve over the entire real line. The integral symbol ∫ originated with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in 1675, but infinite limits were incorporated during the 19th-century development of rigorous integration theory by Bernhard Riemann.[28] Outside pure mathematics, topological objects like the Möbius strip provide visual symbols for infinity. Independently discovered in 1858 by August Ferdinand Möbius in his unpublished notebooks and by Johann Benedict Listing in Vorstudien für Topologie, the Möbius strip is a non-orientable surface formed by twisting and joining a rectangular strip's ends. Its single-sided, boundaryless nature evokes an infinite loop, as a path along its surface returns to the starting point after traversing twice its length without crossing an edge, symbolizing endless continuity.[29]Philosophical Distinctions: Potential vs. Actual Infinity

The distinction between potential and actual infinity originates with Aristotle, who in his Physics argued that the infinite exists only as potentiality, not as actuality. Potential infinity refers to an unending process that can always continue indefinitely, such as the division of a line segment into smaller parts without end, where each step remains finite but the process has no completion.[30] In contrast, actual infinity denotes a completed infinite whole, like an infinite collection of all natural numbers existing simultaneously as a finished totality, which Aristotle rejected as incoherent and impossible in the physical world because it would imply an untraversable magnitude or an actualized endlessness that contradicts the finitude of substances.[30] This Aristotelian framework persisted through much of Western philosophy, influencing medieval thinkers who viewed actual infinity as metaphysically problematic, often associating it solely with divine attributes. In the 20th century, the distinction was revived in mathematical intuitionism by L.E.J. Brouwer, who rejected actual infinity in favor of potential infinity, insisting that infinite mathematical objects must be constructible through finite mental processes and cannot exist as pre-given completed sets.[31] Brouwer's position emphasized that mathematics is a free creation of the human mind, where potential infinity aligns with ongoing constructions, such as generating sequences step by step, without assuming a fully realized infinite domain.[31] Hermann Weyl further critiqued actual infinity in his 1918 work Das Kontinuum, drawing on intuitionistic ideas to argue that the classical continuum relies on an untenable actual infinite, proposing instead a predicative analysis grounded in potential infinite processes to avoid paradoxes in set theory.[32] Metaphysically, the potential-actual distinction bears on debates over infinite regress, particularly in causation: an actual infinite regress would constitute a completed backward chain of causes without a first cause, which some philosophers deem impossible as it violates the principle that contingent beings require an uncaused ground, whereas potential infinity allows for an unending but never-completed series compatible with a finite universe initiated by a necessary being.[33] This tension underscores broader implications for cosmology, where models positing an actual infinite past (e.g., eternal inflation) clash with finitist views favoring a beginning to avoid explanatory regress.[33]Infinity in Analysis and Calculus

Limits and Infinite Series in Real Analysis

In real analysis, the concept of infinity arises fundamentally in the study of limits of functions as the input approaches infinity, providing a rigorous framework for understanding asymptotic behavior without invoking actual infinite values. The limit , where is a real number, is defined using the epsilon-delta formalism adapted for unbounded domains: for every , there exists such that if , then ./Chapter_2:_Limits/2.5:_Limits_at_Infinity) This definition captures the idea that gets arbitrarily close to for sufficiently large , formalizing the intuitive notion of "approaching" a value at infinity. Such limits are essential in analyzing the long-term behavior of functions, such as in growth rates or decay, and form the basis for theorems like those on rational functions where horizontal asymptotes correspond to these limits./04:_Applications_of_Derivatives/4.06:_Limits_at_Infinity_and_Asymptotes) Infinite series extend this framework to sequences of partial sums, where convergence to infinity plays a key role in determining whether sums to a finite value. A series converges if the sequence of its partial sums converges to a real number , meaning ; otherwise, it diverges, potentially to .[34] To test convergence, criteria like the ratio test, introduced by Augustin-Louis Cauchy, examine the limit : if , the series converges absolutely; if , it diverges; and if , the test is inconclusive.[35] This test is particularly effective for series with factorial or exponential terms, leveraging the growth rate to infer overall behavior. Illustrative examples highlight how infinity manifests in series convergence or divergence. The geometric series converges to for , as the partial sums approach this finite value, but diverges to infinity for ./24:_The_Geometric_Series/24.02:_Infinite_Geometric_Series) In contrast, the harmonic series diverges to infinity, with partial sums where is the Euler-Mascheroni constant, growing logarithmically without bound as established by Leonhard Euler.[36] These cases demonstrate the nuanced role of infinity: convergence tames it to a finite outcome, while divergence embraces unbounded growth. To handle limits and integrals involving infinity more cohesively, real analysis employs the extended real line , which augments the reals with and under a total order where for all real , and arithmetic operations defined such that for finite .[37] This structure facilitates improper integrals like , which converge if the limit is finite, or diverge to otherwise, enabling precise statements about integrability over unbounded intervals./01:_Integration/1.12:_Improper_Integrals) For instance, converges, while diverges, mirroring series behaviors and underscoring infinity's role in quantifying unboundedness.Complex Analysis and Infinite Domains

In complex analysis, the concept of infinity plays a central role in extending the complex plane to a compact surface known as the Riemann sphere. This construction achieves a one-point compactification of the complex plane by adjoining a single point , resulting in the extended complex plane . The Riemann sphere is modeled as the unit sphere in , where points on the sphere excluding the north pole are mapped bijectively to via the stereographic projection . This projection identifies the north pole with , transforming circles and lines in the plane into circles on the sphere, and equips with a metric that ensures compactness and continuity of analytic functions at infinity.[38] To analyze singularities and expansions at infinity, functions are examined through the substitution , which maps neighborhoods of to neighborhoods of . A function has a Laurent series expansion around of the form for , obtained by expanding in powers of around 0 and substituting back. If the principal part (negative powers) has infinitely many nonzero terms, is an essential singularity; otherwise, it may be a pole or removable. The residue at infinity, crucial for global residue theorems, is defined as , ensuring that the sum of all residues in , including at , is zero for meromorphic functions. This formula arises from integrating over large contours and changing variables, highlighting the orientation-reversing nature of the map at infinity.[38]/09%3A_Residue_Theorem/9.06%3A_Residue_at_%E2%88%9E) These tools enable powerful applications in evaluating integrals over infinite domains, particularly real integrals from to . For a function analytic in the upper half-plane except at isolated poles, consider a semicircular contour consisting of the real segment and the upper semicircle of radius . By the residue theorem, for poles inside . As , if the integral over vanishes—often verified using estimates like on via Jordan's lemma—then . Representative examples include , obtained by considering and closing in the upper half-plane where ensures exponential decay on the arc. Such methods extend real analysis limits to complex contours, providing exact evaluations unattainable by elementary means./09%3A_Contour_Integration/9.04%3A_Using_Contour_Integration_to_Solve_Definite_Integrals)[39]Nonstandard Analysis and Infinitesimals

Nonstandard analysis, developed by Abraham Robinson in the 1960s, provides a rigorous framework for incorporating infinitesimals into mathematical analysis, reviving concepts from early calculus while avoiding the paradoxes associated with naive uses of infinitely small quantities.[40] Robinson's approach extends the real numbers to the hyperreal numbers, denoted *ℝ, which include both infinitesimal and infinite elements alongside the standard reals.[41] This extension is constructed using ultrapowers or other model-theoretic tools, ensuring that *ℝ forms an ordered field containing numbers ε such that ε > 0 but |ε| < 1/n for every positive integer n in ℝ.[42] Infinitesimals like ε allow direct formulations of continuity and limits without relying on ε-δ arguments, as a function f is continuous at a point a if f(x) ≈ f(a) for all x infinitesimally close to a, where ≈ denotes difference by an infinitesimal.[41] A key feature of nonstandard analysis is the standard part function, st: *ℝ → ℝ, which maps each finite hyperreal (bounded above and below by standard reals) to the unique standard real it approximates.[42] For a finite hyperreal x, st(x) is the real number r such that x - r is infinitesimal.[41] This function bridges the hyperreals back to standard mathematics; for instance, the derivative of a function f at a is defined as st( (f(a + ε) - f(a)) / ε ) for infinitesimal ε ≠ 0, yielding the same results as standard calculus.[42] The transfer principle underpins much of the theory's power: any first-order logical statement true in the reals ℝ holds in the hyperreals ℝ when restricted to standard elements, and vice versa, provided quantifiers are interpreted over the respective universes.[41] Formally, if φ is a first-order formula with parameters from ℝ, then ℝ ⊨ φ if and only if ℝ ⊨ φ, where φ is the natural extension.[42] This principle enables theorems from real analysis to be "transferred" to *ℝ, facilitating proofs that mirror intuitive infinitesimal reasoning. Nonstandard analysis resolves historical paradoxes like Zeno's by treating infinite processes through infinitesimals, such as expressing the sum of an infinite geometric series of distances as a finite hyperreal composed of infinitely many infinitesimal terms that add up exactly without remainder.[42] In Zeno's dichotomy paradox, for example, the total distance traversed is the standard part of an infinite sum ∑ ε / 2^k over hypernatural indices, equaling 1 precisely in *ℝ.[42] This approach avoids supertasks by working within a single, extended number system rather than sequential limits.[41]Set Theory and Infinite Cardinals

Axiomatic Foundations of Infinite Sets

The axiomatic foundations of infinite sets were established primarily through Ernst Zermelo's 1908 axiomatization of set theory, which provided a rigorous framework to avoid the paradoxes arising from naive set comprehension in the late 19th century. Zermelo's system, later refined into Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory (ZF), includes axioms that systematically construct sets while ensuring the existence of infinite collections without leading to inconsistencies. Central to this is the distinction between finite and infinite sets, formalized through specific postulates that guarantee the availability of unbounded structures like the natural numbers. The axiom of infinity, introduced by Zermelo, explicitly postulates the existence of at least one infinite set, serving as the foundational assumption for all infinite mathematics in ZF. Formally, it states that there exists a set such that the empty set is an element of , and for every , the set is also in . This inductive construction yields the von Neumann ordinal , which is isomorphic to the set of natural numbers , providing the smallest infinite well-ordered set. Without this axiom, ZF proves only the existence of finite sets, rendering the theory finitistic. To represent well-ordered infinite sets, John von Neumann developed a hierarchical construction of ordinals in 1923, defining each ordinal as the transitive set of all preceding ordinals under the membership relation. Specifically, finite ordinals are the natural numbers, where , , , and so on, extending to . This von Neumann hierarchy ensures that every well-ordered set is order-isomorphic to a unique ordinal, facilitating transfinite induction and recursion on infinite structures. The ordinals form a proper class under the ZF axioms, with no largest ordinal, enabling the enumeration of increasingly larger infinite sets.[43] Larger infinities arise from the power set axiom and the axiom schema of replacement, both integral to ZF. The power set axiom asserts that for any set , there exists a set whose elements are exactly the subsets of , implying for any infinite , thus generating strictly larger cardinalities iteratively from . For instance, applying the power set to yields the continuum , which has cardinality greater than . The replacement schema, added by Abraham Fraenkel in 1922, states that for any set and definable function , the image is a set, allowing the uniform substitution of elements to produce sets of arbitrary size from existing ones, such as mapping to higher ordinals via transfinite functions. Together, these axioms enable the construction of the entire von Neumann hierarchy for ordinals , where , , and for limit , encompassing all sets in ZF. A set-theoretic characterization of infinity independent of ordering was provided by Richard Dedekind in 1888, defining a set as infinite (Dedekind-infinite) if it admits a bijection with one of its proper subsets. Equivalently, a set is Dedekind-infinite if there exists an injective function that is not surjective. For example, the natural numbers are Dedekind-infinite via the shift , which maps bijectively to . In ZF, every infinite set is Dedekind-infinite, but without the axiom of choice, Dedekind-finite infinite sets (infinite but not bijectable to proper subsets) can exist in certain models. This definition predates axiomatic set theory and highlights infinity as a property of equipotence rather than mere non-finiteness.[44]Cardinality and the Continuum Hypothesis

In set theory, cardinality measures the "size" of sets, with two sets having the same cardinality if there exists a bijection between them. Infinite sets introduce a hierarchy of cardinalities, beginning with the smallest infinite cardinal , which denotes the cardinality of the natural numbers and any countably infinite set, such as the integers or rationals. Georg Cantor introduced this notation in his foundational work on transfinite numbers, establishing as the cardinality of sets that can be enumerated in a sequence without end.[45] The cardinality of the continuum, denoted or , represents the size of the set of real numbers , which Cantor proved is uncountable and thus strictly larger than . This result follows from Cantor's diagonal argument, showing no bijection exists between and . The power set of any set , consisting of all subsets of , exemplifies this growth in cardinality. Cantor's theorem asserts that for any set , , implying that iterating the power set operation generates an unending hierarchy of larger infinite cardinals.[45] The continuum hypothesis (CH), proposed by Cantor, conjectures that no cardinal exists strictly between and , so , the next cardinal after . In 1940, Kurt Gödel demonstrated that CH is consistent with the Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC), by constructing the inner model (the constructible universe) where CH holds. Complementing this, Paul Cohen in 1963 proved CH's independence from ZFC using his forcing technique to build models where , establishing that neither CH nor its negation can be derived from ZFC alone, assuming ZFC's consistency.[46][47] Beyond the initial cardinals, set theory posits even larger ones with special properties. An inaccessible cardinal is an uncountable regular strong limit cardinal, meaning it cannot be reached from smaller cardinals via successor operations or power sets, and it exceeds all smaller cardinals in a limit fashion. Measurable cardinals, a stronger notion introduced by Stanisław Ulam, are uncountable cardinals admitting a non-principal ultrafilter that is -complete, allowing a "measure" on subsets of analogous to probability measures but for infinite sets. These large cardinals extend the hierarchy and have implications for consistency strength in set theory, though their existence is independent of ZFC.[48][49]Geometry and Infinite Structures

Infinite-Dimensional Spaces

Infinite-dimensional spaces extend the concept of finite-dimensional vector spaces to settings where the dimension is infinite, allowing for the study of structures like function spaces that cannot be captured by finite bases. These spaces are fundamental in functional analysis, where they model phenomena involving infinitely many parameters, such as sequences or continuous functions. A key example is the Hilbert space, which is a complete inner product space over the real numbers or complex numbers , equipped with a norm induced by the inner product defined by .[50] Completeness ensures that every Cauchy sequence converges within the space, making Hilbert spaces Banach spaces as well, though the inner product provides additional geometric structure like orthogonality.[50] A prototypical Hilbert space is , the space of square-summable sequences where , with inner product .[51] In infinite-dimensional spaces, the notion of basis differs significantly from the finite case. A Hamel basis, named after Georg Hamel, is a linearly independent set that spans the space via finite linear combinations, analogous to finite-dimensional bases but requiring the axiom of choice for existence in infinite dimensions.[52] However, Hamel bases are often uncountable and not useful for analysis, as they do not respect convergence properties. In contrast, a Schauder basis consists of vectors such that every element in the space can be uniquely expressed as an infinite convergent series , where coefficients are given by continuous linear functionals.[53] Hilbert spaces admit countable orthonormal Schauder bases, where the basis vectors are orthogonal and normalized (), allowing Parseval's identity: .[54] These bases facilitate expansions similar to orthogonal projections in finite dimensions. Banach spaces generalize Hilbert spaces by requiring only completeness with respect to a norm, without an inner product, and are crucial for studying non-Hilbertian infinite-dimensional settings like , the space of continuous functions on with the sup norm .[55] Introduced by Stefan Banach in his 1932 monograph Théorie des opérations linéaires, these spaces form the foundation for operator theory and differential equations in infinite dimensions.[56] Unlike Hilbert spaces, not all Banach spaces have Schauder bases; for instance, some require more complex decompositions.[55] Applications in functional analysis highlight the power of these spaces, particularly through Fourier series expansions. In the Hilbert space of square-integrable functions, the orthonormal basis of complex exponentials allows any to be represented as , where , converging in the norm by the Riesz-Fischer theorem.[57] This framework, building on earlier work by Riesz and Fischer, enables the analysis of partial differential equations and signal processing by decomposing functions into infinite orthogonal components.[57] The infinite dimensionality ensures that such expansions capture essential behaviors in physical systems, like wave propagation, without finite truncation errors dominating.[58]Fractals and Infinite Self-Similarity

Fractals represent a class of geometric objects defined by their infinite detail and fractional dimensions, diverging from the smooth curves and surfaces of classical Euclidean geometry. These structures exhibit self-similarity, meaning they replicate their overall shape at progressively smaller scales, resulting in patterns that remain invariant under magnification. This property leads to infinite complexity confined within bounded regions, challenging traditional notions of dimension and scale. The concept of fractals was formalized by Benoit Mandelbrot, who coined the term in 1975 in his book Les objets fractals: Forme, hasard et dimension, drawing from the Latin fractus to evoke irregularity and fragmentation. A hallmark of fractals is their iterative construction, which generates infinite elaboration through repeated application of simple rules. The Koch snowflake provides a classic example: beginning with an equilateral triangle of side length 1, each iteration replaces the middle third of every line segment with two segments forming the sides of a smaller equilateral triangle pointing outward, with each new segment one-third the length of the previous. After infinitely many iterations, the resulting closed curve encloses a finite area of times the original triangle's area but possesses an infinite perimeter, as the length multiplies by at each step, diverging to infinity. This construction, originally introduced by Helge von Koch in 1904 as a continuous but nowhere differentiable curve, illustrates how iterative processes can yield paradoxical properties: bounded extent with unbounded boundary detail.[59] Similarly, the Mandelbrot set emerges from iterating the quadratic map in the complex plane, starting from , where is a complex parameter. The set consists of all for which the sequence remains bounded, rather than escaping to infinity; its boundary reveals boundless intricacy upon magnification, with self-similar motifs recurring at every level. First visualized by Mandelbrot in 1980, this set exemplifies how dynamical iterations produce fractal structures with infinite nesting of detail, where zooming into the boundary uncovers ever-finer copies of the overall form.[60] The degree of this infinite self-similarity is quantified by the Hausdorff dimension, a measure that extends the integer dimensions of Euclidean spaces to non-integer values reflecting scaling behavior. For self-similar fractals satisfying the open set condition, the Hausdorff dimension equals the similarity dimension, calculated as where is the number of self-similar copies at each iteration and is the linear scaling factor (with ). For instance, the Cantor set—formed by iteratively removing the open middle third from the interval [0,1], leaving two copies scaled by at each step—has Hausdorff dimension , indicating a "dust" more filled than points (dimension 0) but less than a line (dimension 1). This fractional dimension captures the infinite complexity: the set is uncountable yet has zero Lebesgue measure, embodying endless subdivision without filling space. Such properties underscore fractals' role in modeling irregular phenomena with precise mathematical rigor.Finitism and Constructive Approaches

Finitist Critiques in Mathematics

Finitism in mathematics represents a philosophical stance that restricts mathematical inquiry to finite methods and objects, rejecting the acceptance of actual infinity as a coherent concept. This approach emphasizes constructions that can be explicitly verified through finite processes, viewing infinite entities as illusory or unnecessary. A seminal expression of finitism came from Leopold Kronecker, who in the 1880s articulated his belief that mathematics should be grounded solely in the integers, famously stating, "God made the integers; all else is the work of man."[61] Kronecker's critique targeted emerging ideas in analysis and set theory, arguing that non-integer constructs like irrationals and transcendentals lack a divine or fundamental basis and should be derived only through finite integer operations if at all.[61] Ultrafinitism extends finitist skepticism further by questioning even very large finite numbers, treating them as practically indistinguishable from infinity due to insurmountable computational barriers. Proponents argue that numbers beyond feasible computation—such as those exceeding the observable universe's particle count—cannot be meaningfully distinguished or manipulated, rendering claims about them empty.[62] Key figures include Alexander Yessenin-Volpin, who in the 1960s–1970s proposed rejecting the entire series of natural numbers as uniquely defined, and Edward Nelson, whose 1970s work on predicative arithmetic limited induction to avoid assuming an infinite domain of naturals.[62] Rohit Parikh's 1971 analysis formalized this by introducing a feasibility predicate, demonstrating that Peano arithmetic plus the negation of feasibility for remains consistent under computational constraints, highlighting how proof lengths can exceed practical limits.[62] Predicativism, a related finitist variant, specifically avoids impredicative definitions that quantify over totalities including the entity being defined, as these risk circularity and presuppose infinite structures. This concern arose in response to paradoxes in early set theory, with Henri Poincaré in 1906 warning that such definitions violate the vicious circle principle by defining objects in terms of collections they help form.[63] Hermann Weyl advanced this in his 1918 monograph Das Kontinuum, developing a predicative analysis of the real numbers through finite approximations and explicit constructions, eschewing impredicative least upper bounds to maintain foundational rigor.[64] Bertrand Russell's early type theory (1908) also incorporated predicative restrictions to avert paradoxes, prioritizing definitions built sequentially from previously established finite entities.[63] These finitist critiques influence modern mathematics by underscoring limitations in proof verification, particularly in automated theorem proving where exponential proof lengths render many classical results computationally infeasible. Pavel Pudlák's analysis shows that while strong theories like Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory prove finite consistency statements in polynomial time, weaker finitist fragments require superpolynomial lengths, aligning with ultrafinitist views on practical infinity.[65] In automated systems like resolution provers, lower bounds on proof sizes—such as exponential for pigeonhole principles—echo finitist demands for verifiable, bounded constructions, often targeting axioms like the axiom of infinity in set theory as sources of unbounded growth.[65]Intuitionism and Finite Constructions