Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

Rain is a form of precipitation where water droplets that have condensed from atmospheric water vapor fall by gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is responsible for depositing most of the fresh water on the Earth. It provides water for hydroelectric power plants, crop irrigation, and suitable conditions for many types of ecosystems.

The major cause of rain production is moisture moving along three-dimensional zones of temperature and moisture contrasts known as weather fronts. If enough moisture and upward motion is present, precipitation falls from convective clouds (those with strong upward vertical motion) such as cumulonimbus (thunder clouds) which can organize into narrow rainbands. In mountainous areas, heavy precipitation is possible where upslope flow is maximized within windward sides of the terrain at elevation which forces moist air to condense and fall out as rainfall along the sides of mountains. On the leeward side of mountains, desert climates can exist due to the dry air caused by downslope flow which causes heating and drying of the air mass. The movement of the monsoon trough, or Intertropical Convergence Zone, brings rainy seasons to savannah climes.

The urban heat island effect leads to increased rainfall, both in amounts and intensity, downwind of cities. Global warming is also causing changes in the precipitation pattern, including wetter conditions across eastern North America and drier conditions in the tropics. Antarctica is the driest continent. The globally averaged annual precipitation over land is 715 mm (28.1 in), but over the whole Earth, it is much higher at 990 mm (39 in).[1] Climate classification systems such as the Köppen classification system use average annual rainfall to help differentiate between differing climate regimes. Rainfall is measured using rain gauges. Rainfall amounts can be estimated by weather radar.

Formation

[edit]Water-saturated air

[edit]Air contains water vapor, and the amount of water in a given mass of dry air, known as the mixing ratio, is measured in grams of water per kilogram of dry air (g/kg).[2][3] The amount of moisture in the air is also commonly reported as relative humidity; which is the percentage of the total water vapor air can hold at a particular air temperature.[4] How much water vapor a parcel of air can contain before it becomes saturated (100% relative humidity) and forms into a cloud (a group of visible tiny water or ice particles suspended above the Earth's surface)[5] depends on its temperature. Warmer air can contain more water vapor than cooler air before becoming saturated. Therefore, one way to saturate a parcel of air is to cool it. The dew point is the temperature to which a parcel must be cooled in order to become saturated.[6]

There are four main mechanisms for cooling the air to its dew point: adiabatic cooling, conductive cooling, radiational cooling, and evaporative cooling. Adiabatic cooling occurs when air rises and expands.[7] The air can rise due to convection, large-scale atmospheric motions, or a physical barrier such as a mountain (orographic lift). Conductive cooling occurs when the air comes into contact with a colder surface,[8] usually by being blown from one surface to another, for example from a liquid water surface to colder land. Radiational cooling occurs due to the emission of infrared radiation, either by the air or by the surface underneath.[9] Evaporative cooling occurs when moisture is added to the air through evaporation, which forces the air temperature to cool to its wet-bulb temperature, or until it reaches saturation.[10]

The main ways water vapor is added to the air are wind convergence into areas of upward motion,[11] precipitation or virga falling from above,[12] daytime heating evaporating water from the surface of oceans, water bodies or wet land,[13] transpiration from plants,[14] cool or dry air moving over warmer water,[15] and lifting air over mountains.[16] Water vapor normally begins to condense on condensation nuclei such as dust, ice, and salt in order to form clouds. Elevated portions of weather fronts (which are three-dimensional in nature)[17] force broad areas of upward motion within the Earth's atmosphere which form clouds decks such as altostratus or cirrostratus.[18] Stratus is a stable cloud deck which tends to form when a cool, stable air mass is trapped underneath a warm air mass. It can also form due to the lifting of advection fog during breezy conditions.[19]

Coalescence and fragmentation

[edit]

- Contrary to popular belief, raindrops are never tear-shaped.

- Very small raindrops are almost spherical.

- Larger raindrops become flattened at the bottom due to air resistance.

- Large raindrops have a large amount of air resistance, and begin to become unstable.

- Very large raindrops split into smaller raindrops due to air resistance.

Coalescence occurs when water droplets fuse to create larger water droplets.[20] Air resistance typically causes the water droplets in a cloud to remain stationary. When air turbulence occurs, water droplets collide, producing larger droplets.[21][22]

As these larger water droplets descend, coalescence continues, so that drops become heavy enough to overcome air resistance and fall as rain. Coalescence generally happens most often in clouds above freezing (in their top) and is also known as the warm rain process.[23] In clouds below freezing, when ice crystals gain enough mass they begin to fall. This generally requires more mass than coalescence when occurring between the crystal and neighboring water droplets. This process is temperature dependent, as supercooled water droplets only exist in a cloud that is below freezing. In addition, because of the great temperature difference between cloud and ground level, these ice crystals may melt as they fall and become rain.[24]

Raindrops have sizes ranging from 0.1 to 9 mm (0.0039 to 0.3543 in) mean diameter but develop a tendency to break up at larger sizes. Smaller drops are called cloud droplets, and their shape is spherical. As a raindrop increases in size, its shape becomes more oblate, with its largest cross-section facing the oncoming airflow. Large rain drops become increasingly flattened on the bottom, like hamburger buns; very large ones are shaped like parachutes.[25][26] Contrary to popular belief, their shape does not resemble a teardrop.[27] The biggest raindrops on Earth were recorded over Brazil and the Marshall Islands in 2004 — some of them were as large as 10 mm (0.39 in). The large size is explained by condensation on large smoke particles or by collisions between drops in small regions with particularly high content of liquid water.[28]

Raindrops associated with melting hail tend to be larger than other raindrops.[29]

Intensity and duration of rainfall are usually inversely related, i.e., high-intensity storms are likely to be of short duration and low-intensity storms can have a long duration.[30][31]

Droplet size distribution

[edit]The final droplet size distribution is an exponential distribution. The number of droplets with diameter between and per unit volume of space is . This is commonly referred to as the Marshall–Palmer law after the researchers who first characterized it.[26][32] The parameters are somewhat temperature-dependent,[33] and the slope also scales with the rate of rainfall (d in centimeters and R in millimeters per hour).[26]

Deviations can occur for small droplets and during different rainfall conditions. The distribution tends to fit averaged rainfall, while instantaneous size spectra often deviate and have been modeled as gamma distributions.[34] The distribution has an upper limit due to droplet fragmentation.[26]

Raindrop impacts

[edit]Raindrops impact at their terminal velocity, which is greater for larger drops due to their larger mass-to-drag ratio. At sea level and without wind, 0.5 mm (0.020 in) drizzle impacts at 2 m/s (6.6 ft/s) or 7.2 km/h (4.5 mph), while large 5 mm (0.20 in) drops impact at around 9 m/s (30 ft/s) or 32 km/h (20 mph).[35]

Rain falling on loosely packed material such as newly fallen ash can produce dimples that can be fossilized, called raindrop impressions.[36] The air density dependence of the maximum raindrop diameter together with fossil raindrop imprints has been used to constrain the density of the air 2.7 billion years ago.[37] The sound of raindrops hitting water is caused by bubbles of air oscillating underwater.[38][39]

The METAR code for rain is RA, while the coding for rain showers is SHRA.[40]

Virga

[edit]In certain conditions, precipitation may fall from a cloud but then evaporate or sublime before reaching the ground. This is termed virga, also known as "fallstreaks" or "precipitation trails",[41] and also refers to an optical phenomenon where the brightness of precipitation appears to abruptly change under a cloud.[42] Virga is common in hot and arid climates,[43] but has been recorded in the Arctic[44] and Antarctica[45] and is known to occur on planets beyond Earth, including Mars[46] and Venus.[47]

Causes

[edit]Frontal activity

[edit]Stratiform (a broad shield of precipitation with a relatively similar intensity) and dynamic precipitation (convective precipitation which is showery in nature with large changes in intensity over short distances) occur as a consequence of slow ascent of air in synoptic systems (on the order of cm/s), such as in the vicinity of cold fronts and near and poleward of surface warm fronts. Similar ascent is seen around tropical cyclones outside the eyewall, and in comma-head precipitation patterns around mid-latitude cyclones.[48]

A wide variety of weather can be found along an occluded front, with thunderstorms possible, but usually, their passage is associated with a drying of the air mass. Occluded fronts usually form around mature low-pressure areas.[49] What separates rainfall from other precipitation types, such as ice pellets and snow, is the presence of a thick layer of air aloft which is above the melting point of water, which melts the frozen precipitation well before it reaches the ground. If there is a shallow near-surface layer that is below freezing, freezing rain (rain which freezes on contact with surfaces in subfreezing environments) will result.[50] Hail becomes an increasingly infrequent occurrence when the freezing level within the atmosphere exceeds 3,400 m (11,000 ft) above ground level.[51]

Convection

[edit]

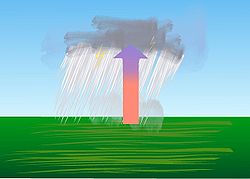

Convective rain, or showery precipitation, occurs from convective clouds (e.g., cumulonimbus or cumulus congestus). It falls as showers with rapidly changing intensity. Convective precipitation falls over a certain area for a relatively short time, as convective clouds have limited horizontal extent. Most precipitation in the tropics appears to be convective; however, it has been suggested that stratiform precipitation also occurs.[48][52] Graupel and hail indicate convection.[53] In mid-latitudes, convective precipitation is intermittent and often associated with baroclinic boundaries such as cold fronts, squall lines, and warm fronts.[54]

Orographic effects

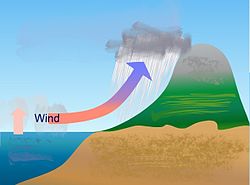

[edit]Orographic precipitation occurs on the windward side of mountains and is caused by the rising air motion of a large-scale flow of moist air across the mountain ridge, resulting in adiabatic cooling and condensation. In mountainous parts of the world subjected to relatively consistent winds (for example, the trade winds), a more moist climate usually prevails on the windward side of a mountain than on the leeward or downwind side. Moisture is removed by orographic lift, leaving drier air (see katabatic wind) on the descending and generally warming, leeward side where a rain shadow is observed.[16]

In Hawaii, Mount Waiʻaleʻale, on the island of Kauai, is notable for its extreme rainfall, as it is amongst the places in the world with the highest levels of rainfall, with 9,500 mm (373 in).[55] Systems known as Kona storms affect the state with heavy rains between October and April.[56] Local climates vary considerably on each island due to their topography, divisible into windward (Koʻolau) and leeward (Kona) regions based upon location relative to the higher mountains. Windward sides face the east to northeast trade winds and receive much more rainfall; leeward sides are drier and sunnier, with less rain and less cloud cover.[57]

In South America, the Andes mountain range blocks Pacific moisture that arrives in that continent, resulting in a desert-like climate just downwind across western Argentina.[58] The Sierra Nevada range creates the same effect in North America forming the Great Basin and Mojave Deserts.[59][60]

Within the tropics

[edit]

The wet, or rainy, season is the time of year, covering one or more months, when most of the average annual rainfall in a region falls.[61] The term green season is also sometimes used as a euphemism by tourist authorities.[62] Areas with wet seasons are dispersed across portions of the tropics and subtropics.[63] Savanna climates and areas with monsoon regimes have wet summers and dry winters. Tropical rainforests technically do not have dry or wet seasons, since their rainfall is equally distributed through the year.[64] Some areas with pronounced rainy seasons will see a break in rainfall mid-season when the Intertropical Convergence Zone or monsoon trough move poleward of their location during the middle of the warm season.[30] When the wet season occurs during the warm season, or summer, rain falls mainly during the late afternoon and early evening hours. The wet season is a time when both air quality[65] and freshwater quality improves.[66][67]

Tropical cyclones, a source of very heavy rainfall, consist of large air masses several hundred miles across with low pressure at the centre and with winds blowing inward towards the centre in either a clockwise direction (southern hemisphere) or counterclockwise (northern hemisphere).[68] Although cyclones can take an enormous toll in lives and personal property, they may be important factors in the precipitation regimes of places they impact, as they may bring much-needed precipitation to otherwise dry regions.[69] Areas in their path can receive a year's worth of rainfall from a tropical cyclone passage.[70]

Human influence

[edit]

The fine particulate matter produced by car exhaust and other human sources of pollution forms cloud condensation nuclei leads to the production of clouds and increases the likelihood of rain. As commuters and commercial traffic cause pollution to build up over the course of the week, the likelihood of rain increases: it peaks by Saturday, after five days of weekday pollution has been built up. In heavily populated areas that are near the coast, such as the United States' Eastern Seaboard, the effect can be dramatic: there is a 22% higher chance of rain on Saturdays than on Mondays.[72] The urban heat island effect warms cities 0.6 to 5.6 °C (33.1 to 42.1 °F) above surrounding suburbs and rural areas. This extra heat leads to greater upward motion, which can induce additional shower and thunderstorm activity. Rainfall rates downwind of cities are increased between 48% and 116%. Partly as a result of this warming, monthly rainfall is about 28% greater between 32 and 64 km (20 and 40 mi) downwind of cities, compared with upwind.[73] Some cities induce a total precipitation increase of 51%.[74]

Increasing temperatures tend to increase evaporation which can lead to more precipitation. Precipitation generally increased over land north of 30°N from 1900 through 2005 but has declined over the tropics since the 1970s. Globally there has been no statistically significant overall trend in precipitation over the past century, although trends have varied widely by region and over time. Eastern portions of North and South America, northern Europe, and northern and central Asia have become wetter. The Sahel, the Mediterranean, southern Africa and parts of southern Asia have become drier. There has been an increase in the number of heavy precipitation events over many areas during the past century, as well as an increase since the 1970s in the prevalence of droughts—especially in the tropics and subtropics. Changes in precipitation and evaporation over the oceans are suggested by the decreased salinity of mid- and high-latitude waters (implying more precipitation), along with increased salinity in lower latitudes (implying less precipitation and/or more evaporation). Over the contiguous United States, total annual precipitation increased at an average rate of 6.1 percent since 1900, with the greatest increases within the East North Central climate region (11.6 percent per century) and the South (11.1 percent). Hawaii was the only region to show a decrease (−9.25 percent).[75]

Analysis of 65 years of United States of America rainfall records show the lower 48 states have an increase in heavy downpours since 1950. The largest increases are in the Northeast and Midwest, which in the past decade, have seen 31 and 16 percent more heavy downpours compared to the 1950s. Rhode Island is the state with the largest increase, 104%. McAllen, Texas is the city with the largest increase, 700%. Heavy downpour in the analysis are the days where total precipitation exceeded the top one percent of all rain and snow days during the years 1950–2014.[76][77]

The most successful attempts at influencing weather involve cloud seeding, which include techniques used to increase winter precipitation over mountains and suppress hail.[78]

Characteristics

[edit]Patterns

[edit]

Rainbands are cloud and precipitation areas which are significantly elongated. Rainbands can be stratiform or convective,[79] and are generated by differences in temperature. When noted on weather radar imagery, this precipitation elongation is referred to as banded structure.[80] Rainbands in advance of warm occluded fronts and warm fronts are associated with weak upward motion,[81] and tend to be wide and stratiform in nature.[82]

Rainbands spawned near and ahead of cold fronts can be squall lines which are able to produce tornadoes.[83] Rainbands associated with cold fronts can be warped by mountain barriers perpendicular to the front's orientation due to the formation of a low-level barrier jet.[84] Bands of thunderstorms can form with sea breeze and land breeze boundaries if enough moisture is present. If sea breeze rainbands become active enough just ahead of a cold front, they can mask the location of the cold front itself.[85]

Once a cyclone occludes an occluded front (a trough of warm air aloft) will be caused by strong southerly winds on its eastern periphery rotating aloft around its northeast, and ultimately northwestern, periphery (also termed the warm conveyor belt), forcing a surface trough to continue into the cold sector on a similar curve to the occluded front. The front creates the portion of an occluded cyclone known as its comma head, due to the comma-like shape of the mid-tropospheric cloudiness that accompanies the feature. It can also be the focus of locally heavy precipitation, with thunderstorms possible if the atmosphere along the front is unstable enough for convection.[86] Banding within the comma head precipitation pattern of an extratropical cyclone can yield significant amounts of rain.[87] Behind extratropical cyclones during fall and winter, rainbands can form downwind of relative warm bodies of water such as the Great Lakes. Downwind of islands, bands of showers and thunderstorms can develop due to low-level wind convergence downwind of the island edges. Offshore California, this has been noted in the wake of cold fronts.[88]

Rainbands within tropical cyclones are curved in orientation. Tropical cyclone rainbands contain showers and thunderstorms that, together with the eyewall and the eye, constitute a hurricane or tropical storm. The extent of rainbands around a tropical cyclone can help determine the cyclone's intensity.[89]

Acidity

[edit]

The phrase acid rain was first used by Scottish chemist Robert Augus Smith in 1852.[90] The pH of rain varies, especially due to its origin. On America's East Coast, rain that is derived from the Atlantic Ocean typically has a pH of 5.0–5.6; rain that comes across the continental from the west has a pH of 3.8–4.8; and local thunderstorms can have a pH as low as 2.0.[91] Rain becomes acidic primarily due to the presence of two strong acids, sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and nitric acid (HNO3). Sulfuric acid is derived from natural sources such as volcanoes, and wetlands (sulfate-reducing bacteria); and anthropogenic sources such as the combustion of fossil fuels, and mining where H2S is present. Nitric acid is produced by natural sources such as lightning, soil bacteria, and natural fires; while also produced anthropogenically by the combustion of fossil fuels and from power plants. In the past 20 years, the concentrations of nitric and sulfuric acid has decreased in presence of rainwater, which may be due to the significant increase in ammonium (most likely as ammonia from livestock production), which acts as a buffer in acid rain and raises the pH.[92]

Köppen climate classification

[edit]

The Köppen classification depends on average monthly values of temperature and precipitation. The most commonly used form of the Köppen classification has five primary types labeled A through E. Specifically, the primary types are A, tropical; B, dry; C, mild mid-latitude; D, cold mid-latitude; and E, polar. The five primary classifications can be further divided into secondary classifications such as rain forest, monsoon, tropical savanna, humid subtropical, humid continental, oceanic climate, Mediterranean climate, steppe, subarctic climate, tundra, polar ice cap, and desert.[94]

Rain forests are characterized by high rainfall, with definitions setting minimum normal annual rainfall between 1,750 and 2,000 mm (69 and 79 in).[95] A tropical savanna is a grassland biome located in semi-arid to semi-humid climate regions of subtropical and tropical latitudes, with rainfall between 750 and 1,270 mm (30 and 50 in) a year. They are widespread on Africa, and are also found in India, the northern parts of South America, Malaysia, and Australia.[96] The humid subtropical climate zone is where winter rainfall is associated with large storms that the westerlies steer from west to east. Most summer rainfall occurs during thunderstorms and from occasional tropical cyclones.[97] Humid subtropical climates lie on the east side continents, roughly between latitudes 20° and 40° degrees away from the equator.[98]

An oceanic (or maritime) climate is typically found along the west coasts at the middle latitudes of all the world's continents, bordering cool oceans, as well as southeastern Australia, and is accompanied by plentiful precipitation year-round.[99] The Mediterranean climate regime resembles the climate of the lands in the Mediterranean Basin, parts of western North America, parts of Western and South Australia, in southwestern South Africa and in parts of central Chile. The climate is characterized by hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters.[100] A steppe is a dry grassland.[101] Subarctic climates are cold with continuous permafrost and little precipitation.[102]

Pollution and composition

[edit]Aside from contamination of rainwater by sulfuric and nitric oxides, which produces acid rain, various pollutants from industry and household wastes can end up in rainwater, causing detrimental effects on aquatic and human life. Pollutants from solid waste, leaking vehicles and machinery, fertilizers and other potentially hazardous substances enter water sources directly through dumping or as surface runoff following heavy rain.[103] One classification of pollutants of particular note is perfluoroalkyl substances, synthetic chemical compounds used in a wide variety of consumer products.[104] Rain has the potential to dissolve and transport different compounds, including the aforementioned toxic substances, with certain ions such as calcium and bicarbonate appearing frequently, in more acidic rainwater.[105] However, the composition of rainwater at any given time and place is highly variable based on the ongoing manufacturing, farming, and waste-producing activities.[106]

In 2022, levels of at least four perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in rain water worldwide greatly exceeded the EPA's lifetime drinking water health advisories as well as comparable Danish, Dutch, and European Union safety standards, leading to the conclusion that "the global spread of these four PFAAs in the atmosphere has led to the planetary boundary for chemical pollution being exceeded".[107] The most common PFAS found in the environment is Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA).[108] Its presence is ubiquitous in the environment, especially in aquatic ecosystems, where it persists with increasing concentrations globally.[109]

It had been thought that PFAAs would eventually end up in the oceans, where they would be diluted over decades, but a field study published in 2021 by researchers at Stockholm University found that they are often transferred from water to air when waves reach land, are a significant source of air pollution, and eventually get into rain. The researchers concluded that pollution may impact large areas.[110][111][112] Soil is also contaminated and the chemicals have been found in remote areas such as Antarctica.[113] Soil contamination can result in higher levels of PFAS found in foods such as white rice, coffee, and animals reared on contaminated ground.[114][115][116] In 2024, a worldwide study of 45,000 groundwater samples found that 31% of samples contained levels of PFAS that were harmful to human health; these samples were taken from areas not near any obvious source of contamination.[117]Measurement

[edit]Gauges

[edit]

Rain rate is measured in units of length per unit time, typically in millimeters per hour,[118] or in countries where imperial units are more common, inches per hour.[119] The "length", or more accurately, "depth" being measured is the depth of rain water that would accumulate on a flat, horizontal and impermeable surface during a given amount of time, typically an hour.[120] This is dimensionally equivalent to volume of water per unit area: one millimeter of rainfall is the equivalent of one liter of water per square meter.[121] This measurement is done with a gauge. A cylindrical can with straight sides is the most inexpensive and simple used that can be made and left out in the open, but its accuracy will depend on what ruler is used to measure the rain with.[122] Meteorologists have a standard type of gauge for both rainfall or snowfall with an inner cylinder and an outer cylinder that adds to the volume of the full inner cylinder.[123] Other types of gauges include the popular wedge gauge (the cheapest rain gauge and most fragile), the tipping bucket rain gauge, and the weighing rain gauge.[124]

When a precipitation measurement is made, various networks exist across the United States and elsewhere where rainfall measurements can be submitted through the Internet, such as CoCoRAHS or GLOBE.[125][126] If a network is not available in the area where one lives, the nearest local weather or met office will likely be interested in the measurement.[127]

Remote sensing

[edit]

One of the main uses of weather radar is to be able to assess the amount of precipitations fallen over large basins for hydrological purposes.[128] For instance, river flood control, sewer management and dam construction are all areas where planners use rainfall accumulation data. Radar-derived rainfall estimates complement surface station data which can be used for calibration. To produce radar accumulations, rain rates over a point are estimated by using the value of reflectivity data at individual grid points. A radar equation is then used, which is where Z represents the radar reflectivity, R represents the rainfall rate, and A and b are constants.[129] Satellite-derived rainfall estimates use passive microwave instruments aboard polar orbiting as well as geostationary weather satellites to indirectly measure rainfall rates.[130] If one wants an accumulated rainfall over a time period, one has to add up all the accumulations from each grid box within the images during that time.

Intensity

[edit]Rainfall intensity is classified according to the rate of precipitation, which depends on the considered time.[131] The following categories are used to classify rainfall intensity:

- Light rain – when the precipitation rate is less than 2.5 mm (0.098 in) per hour

- Moderate rain – when the precipitation rate is between 2.5 and 7.6 mm (0.098–0.299 in) or 10 mm (0.39 in) per hour[132][133]

- Heavy rain – when the precipitation rate is greater than 7.6 mm (0.30 in) per hour,[132] or between 10 and 50 mm (0.39–1.97 in) per hour[133]

- Violent rain – when the precipitation rate is greater than 50 mm (2.0 in) per hour[133]

The intensity can also be expressed by rainfall erosivity R-factor[134] or in terms of the rainfall time-structure n-index.[131]

Return period

[edit]The average time between occurrences of an event with a specified intensity and duration is called the return period.[135] The intensity of a storm can be predicted for any return period and storm duration, from charts based on historic data for the location.[136] The return period is often expressed as an n-year event. For instance, a 10-year storm describes a rare rainfall event occurring on average once every 10 years. The rainfall will be greater and the flooding will be worse than the worst storm expected in any single year. A 100-year storm describes an extremely rare rainfall event occurring on average once in a century. The rainfall will be extreme and flooding worse than a 10-year event. The probability of an event in any year is the inverse of the return period (assuming the probability remains the same for each year).[135] For instance, a 10-year storm has a probability of occurring of 10 percent in any given year, and a 100-year storm occurs with a 1 percent probability in a year. As with all probability events, it is possible, though improbable, to have multiple 100-year storms in a single year.[137]

Forecasting

[edit]

The Quantitative Precipitation Forecast (abbreviated QPF) is the expected amount of liquid precipitation accumulated over a specified time period over a specified area.[138] A QPF will be specified when a measurable precipitation type reaching a minimum threshold is forecast for any hour during a QPF valid period. Precipitation forecasts tend to be bound by synoptic hours such as 0000, 0600, 1200 and 1800 GMT. Terrain is considered in QPFs by use of topography or based upon climatological precipitation patterns from observations with fine detail.[139] Starting in the mid to late 1990s, QPFs were used within hydrologic forecast models to simulate impact to rivers throughout the United States.[140]

Forecast models show significant sensitivity to humidity levels within the planetary boundary layer, or in the lowest levels of the atmosphere, which decreases with height.[141] QPF can be generated on a quantitative, forecasting amounts, or a qualitative, forecasting the probability of a specific amount, basis.[142] Radar imagery forecasting techniques show higher skill than model forecasts within 6 to 7 hours of the time of the radar image. The forecasts can be verified through use of rain gauge measurements, weather radar estimates, or a combination of both. Various skill scores can be determined to measure the value of the rainfall forecast.[143]

Impact

[edit]Agricultural

[edit]

Precipitation, especially rain, has a dramatic effect on agriculture. All plants need at least some water to survive, therefore rain (being the most effective means of watering) is important to agriculture. While a regular rain pattern is usually vital to healthy plants, too much or too little rainfall can be harmful, even devastating to crops. Drought can kill crops and increase erosion,[144] while overly wet weather can cause harmful fungus growth.[145] Plants need varying amounts of rainfall to survive.[146] For example, certain cacti require small amounts of water,[147] while crops such as rice require thousands of liters of water to provide good yields and must be continuously irrigated in addition to normal watering through rainfall.[148] Plants that thrive in drier climates thrive in conditions with infrequent, large rainfall events, while plants in wetter ecosystems prefer the opposite: frequent, mild rainfall.[149]

In areas with wet and dry seasons, soil nutrients diminish and erosion increases during the wet season.[30] Animals have adaptation and survival strategies for the wetter regime. The previous dry season leads to food shortages into the wet season, as the crops have yet to mature.[150] Developing countries have noted that their populations show seasonal weight fluctuations due to food shortages seen before the first harvest, which occurs late in the wet season.[151] Rain may be harvested through the use of rainwater tanks; treated to potable use or for non-potable use indoors or for irrigation.[152] Excessive rain during short periods of time can cause flash floods.[153]

Culture and religion

[edit]

Cultural attitudes towards rain differ across the world. In temperate climates, people tend to be more stressed when the weather is unstable or cloudy, with its impact greater on men than women.[154] Rain can also bring joy, as some consider it to be soothing or enjoy the aesthetic appeal of it. In dry places, such as India,[155] or during periods of drought,[156] rain lifts people's moods. In Botswana, the Setswana word for rain, pula, is used as the name of the national currency, in recognition of the economic importance of rain in its country, since it has a desert climate.[157] Several cultures have developed means of dealing with rain and have developed numerous protection devices such as umbrellas and raincoats, and diversion devices such as gutters and storm drains that lead rains to sewers.[158] Many people find the scent during and immediately after rain pleasant or distinctive. The source of this scent is petrichor, an oil produced by plants, then absorbed by rocks and soil, and later released into the air during rainfall.[159]

Rain holds an important religious significance in many cultures.[160] The ancient Sumerians believed that rain was the semen of the sky god An,[161] which fell from the heavens to inseminate his consort, the earth goddess Ki,[161] causing her to give birth to all the plants of the earth.[161] The Akkadians believed that the clouds were the breasts of Anu's consort Antu[161] and that rain was milk from her breasts.[161] According to Jewish tradition, in the first century BC, the Jewish miracle-worker Honi ha-M'agel ended a three-year drought in Judaea by drawing a circle in the sand and praying for rain, refusing to leave the circle until his prayer was granted.[162] In his Meditations, the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius preserves a prayer for rain made by the Athenians to the Greek sky god Zeus.[160] Various Native American tribes are known to have historically conducted rain dances in effort to encourage rainfall.[160] Rainmaking rituals are also important in many African cultures.[163] In the present-day United States, various state governors have held Days of Prayer for rain, including the Days of Prayer for Rain in the State of Texas in 2011.[160]

Global climatology

[edit]Approximately 505,000 km3 (121,000 cu mi) of water falls as precipitation each year across the globe with 398,000 km3 (95,000 cu mi) of it over the oceans.[164] Given the Earth's surface area, that means the globally averaged annual precipitation is 990 mm (39 in). Deserts are defined as areas with an average annual precipitation of less than 250 mm (10 in) per year,[165][166] or as areas where more water is lost by evapotranspiration than falls as precipitation.[167]

Deserts

[edit]

The northern half of Africa is dominated by the world's most extensive hot, dry region, the Sahara Desert. Some deserts also occupy much of southern Africa: the Namib and the Kalahari. Across Asia, a large annual rainfall minimum, composed primarily of deserts, stretches from the Gobi Desert in Mongolia west-southwest through western Pakistan (Balochistan) and Iran into the Arabian Desert in Saudi Arabia. Most of Australia is semi-arid or desert,[168] making it the world's driest inhabited continent. In South America, the Andes mountain range blocks Pacific moisture that arrives in that continent, resulting in a desert-like climate just downwind across western Argentina.[58] The drier areas of the United States are regions where the Sonoran Desert overspreads the Desert Southwest, the Great Basin, and central Wyoming.[169]

Polar deserts

[edit]Since rain only falls as liquid, it rarely falls when surface temperatures are below freezing unless there is a layer of warm air aloft, in which case it becomes freezing rain. Due to the entire atmosphere being below freezing, frigid climates usually see very little rainfall and are often known as polar deserts. A common biome in this area is the tundra, which has a short summer thaw and a long frozen winter. Rainfall in these polar deserts and precipitation in general is very low, though they cannot be described as arid, as the soil is predictably moist during brief growing seasons and air humidity remains relatively high, with evaporation rates being very low.[170] Due to its location, Antarctica is home to the driest regions in the world.[171]

Rainforests

[edit]Rainforests are characterized mainly as areas of the world with very high humidity. Tropical and temperate rainforests exist, as do the less common dry rainforests.[172] Tropical rainforests occupy a large band of the planet, mainly along the equator, as climates associated with tropical rainforests are most often found within ten degrees of latitude of the equator. They do not experience natural seasons as do many other regions, with the average daylight hours and temperatures remaining fairly constant throughout the year.[173] Temperate rainforests are often located much further from the equator, but still have high rainfall and in many cases have a closed tree canopy.[174] Dry rainforests maintain a dense canopy, but can face periods of drought.[175][172]

Monsoons

[edit]The equatorial region near the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), or monsoon trough, is the wettest portion of the world's continents. Annually, the rain belt within the tropics marches northward by August, then moves back southward into the Southern Hemisphere by February and March.[176] Within Asia, rainfall is favored across its southern portion from India east and northeast across the Philippines and southern China into Japan due to the monsoon advecting moisture primarily from the Indian Ocean into the region.[177] The monsoon trough can reach as far north as the 40th parallel in East Asia during August before moving southward after that. Its poleward progression is accelerated by the onset of the summer monsoon, which is characterized by the development of lower air pressure (a thermal low) over the warmest part of Asia.[178][179] Similar, but weaker, monsoon circulations are present over North America and Australia.[180][181]

During the summer, the Southwest monsoon combined with Gulf of California and Gulf of Mexico moisture moving around the subtropical ridge in the Atlantic Ocean brings the promise of afternoon and evening thunderstorms to the southern tier of the United States as well as the Great Plains.[182] The eastern half of the contiguous United States east of the 98th meridian, the mountains of the Pacific Northwest, and the Sierra Nevada range are the wetter portions of the nation, with average rainfall exceeding 760 mm (30 in) per year.[183] Tropical cyclones enhance precipitation across southern sections of the United States,[184] as well as Puerto Rico, the United States Virgin Islands,[185] the Northern Mariana Islands,[186] Guam,[187] and American Samoa.[188]

Impact of the Westerlies

[edit]

Westerly flow from the mild North Atlantic leads to wetness across western Europe, in particular Ireland and the United Kingdom, where the western coasts can receive between 1,000 mm (39 in), at sea level and 2,500 mm (98 in), on the mountains of rain per year. Bergen, Norway is one of the more famous European rain-cities with its yearly precipitation of 2,250 mm (89 in) on average. During the fall, winter, and spring, Pacific storm systems bring most of Hawaii and the western United States much of their precipitation.[182] Over the top of the ridge, the jet stream brings a summer precipitation maximum to the Great Lakes. Large thunderstorm areas known as mesoscale convective complexes move through the Plains, Midwest, and Great Lakes during the warm season, contributing up to 10% of the annual precipitation to the region.[189]

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation affects the precipitation distribution by altering rainfall patterns across the western United States,[190] Midwest,[191][192] the Southeast,[193] and throughout the tropics. There is also evidence that global warming leads to increased precipitation and higher frequency of extreme precipitation events in the eastern portions of North America, while rainfall is becoming less frequent and in lower amounts in the tropics, subtropics, and the western United States.[194]

Wettest known locations

[edit]Cherrapunji, situated on the southern slopes of the Eastern Himalaya in Shillong, India, is the confirmed wettest place on Earth, with an average annual rainfall of 11,430 mm (450 in). The highest recorded rainfall in a single year was 22,987 mm (905.0 in) in 1861. The 38-year average at nearby Mawsynram, Meghalaya, India, is 11,873 mm (467.4 in).[195] The wettest spot in Australia is Mount Bellenden Ker in the north-east of the country which records an average of 8,000 mm (310 in) per year, with over 12,200 mm (480.3 in) of rain recorded during 2000.[196] The Big Bog on the island of Maui has the highest average annual rainfall in the Hawaiian Islands, at 10,300 mm (404 in).[197] Mount Waiʻaleʻale on the island of Kauaʻi achieves similar torrential rains, while slightly lower than that of the Big Bog, at 9,500 mm (373 in)[198] of rain per year over the last 32 years, with a record 17,340 mm (683 in) in 1982. Its summit is considered one of the rainiest spots on earth, with a reported 360 days of rain per year.[199]

Lloró, a town situated in Chocó, Colombia, is probably the place with the largest rainfall in the world, averaging 13,300 mm (523.6 in) per year.[200] The Department of Chocó is extraordinarily humid. Tutunendaó, a small town situated in the same department, is one of the wettest estimated places on Earth, averaging 11,394 mm (448.6 in) per year; in 1974 the town received 26,303 mm (86 ft 3.6 in), the largest annual rainfall measured in Colombia. Unlike Cherrapunji, which receives most of its rainfall between April and September, Tutunendaó receives rain almost uniformly distributed throughout the year.[201] Quibdó, the capital of Chocó, receives the most rain in the world among cities with over 100,000 inhabitants: 9,000 mm (354 in) per year.[200]

| Continent | Highest average | Place | Elevation | Years of record | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in | mm | ft | m | |||

| South America | 523.6 | 13,299 | Lloró, Colombia (estimated)[a][b] | 520 | 158[c] | 29 |

| Asia | 467.4 | 11,872 | Mawsynram, India[a][d] | 4,597 | 1,401 | 39 |

| Africa | 405.0 | 10,287 | Debundscha, Cameroon | 30 | 9.1 | 32 |

| Oceania | 404.3 | 10,269 | Big Bog, Maui, Hawaii (US)[a] | 5,148 | 1,569 | 30 |

| South America | 354.0 | 8,992 | Quibdo, Colombia | 120 | 36.6 | 16 |

| Australia | 340.0 | 8,636 | Mount Bellenden Ker, Queensland | 5,102 | 1,555 | 9 |

| North America | 256.0 | 6,502 | Hucuktlis Lake, British Columbia | 12 | 3.66 | 14 |

| Europe | 183.0 | 4,648 | Crkvice, Montenegro | 3,337 | 1,017 | 22 |

| Source (without conversions): Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation, National Climatic Data Center. 9 August 2004.[202] | ||||||

| Continent | Place | Highest rainfall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| in | mm | |||

| Highest average annual rainfall[203] | Asia | Mawsynram, India | 467.4 | 11,870 |

| Highest in one year[203] | Asia | Cherrapunji, India | 1,042 | 26,470 |

| Highest in one calendar month[204] | Asia | Cherrapunji, India | 366 | 9,296 |

| Highest in 24 hours[203] | Indian Ocean | Foc Foc, La Réunion | 71.8 | 1,820 |

| Highest in 12 hours[203] | Indian Ocean | Foc Foc, La Réunion | 45.0 | 1,140 |

| Highest in one minute[203] | North America | Unionville, Maryland, US | 1.23 | 31.2 |

See also

[edit]- Aquifer storage and recovery

- Atmospheric river

- Bioswale

- Blue roof

- Cistern

- Hydropower

- Integrated urban water management

- Intensity-duration-frequency curve

- Johad

- Permeable paving

- Petrichor – the cause of the scent during and after rain

- Precipitation types

- Rain dust

- Rain garden

- Rain sensor

- Rainbow

- Raining animals

- Rainmaking

- Rainwater harvesting

- Rainwater management

- Red rain

- Red rain in Kerala

- Sanitary sewer overflow

- Sediment precipitation

- Vortex filter

- Water resources

- Water-sensitive urban design

- Weather

Notes

[edit]- a b c The value given is the continent's highest, and possibly the world's, depending on measurement practices, procedures and period of record variations.

- ^ The official greatest average annual precipitation for South America is 900 cm (354 in) at Quibdó, Colombia. The 1,330 cm (523.6 in) average at Lloró [23 km (14 mi) SE and at a higher elevation than Quibdó] is an estimated amount.

- ^ Approximate elevation.

- ^ Recognized as "The Wettest place on Earth" by the Guinness Book of World Records.[205]

- ^ This is the highest figure for which records are available. The summit of Mount Snowdon, about 500 yards (460 m) from Glaslyn, is estimated to have at least 200.0 inches (5,080 mm) per year.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Water Cycle". Planetguide.net. Archived from the original on 26 December 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Steve Kempler (2009). "Parameter information page". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 26 November 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Mark Stoelinga (12 September 2005). Atmospheric Thermodynamics (PDF). University of Washington. p. 80. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Relative Humidity". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Cloud". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command (2007). "Atmospheric Moisture". United States Navy. Archived from the original on 14 January 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Adiabatic Process". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ TE Technology, Inc (2009). "Peltier Cold Plate". Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Radiational cooling". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Robert Fovell (2004). "Approaches to saturation" (PDF). University of California in Los Angeles. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ Robert Penrose Pearce (2002). Meteorology at the Millennium. Academic Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-12-548035-2. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ "Virga and Dry Thunderstorms". National Weather Service. Spokane, WA. 2009. Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Bart van den Hurk & Eleanor Blyth (2008). "Global maps of Local Land-Atmosphere coupling" (PDF). KNMI. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Krishna Ramanujan & Brad Bohlander (2002). "Landcover changes may rival greenhouse gases as cause of climate change". National Aeronautics and Space Administration Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 3 June 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ National Weather Service JetStream (2008). "Air Masses". Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ a b Michael Pidwirny (2008). "CHAPTER 8: Introduction to the Hydrosphere (e). Cloud Formation Processes". Physical Geography. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Front". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ^ David Roth. "Unified Surface Analysis Manual" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ FMI (2007). "Fog And Stratus – Meteorological Physical Background". Zentralanstalt für Meteorologie und Geodynamik. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ Klyuzhin, Ivan S.; Ienna, Federico; Roeder, Brandon; Wexler, Adam; Pollack, Gerald H. (2010-11-11). "Persisting water droplets on water surfaces". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 114 (44): 14020–14027. doi:10.1021/jp106899k. ISSN 1520-5207. PMC 3208511. PMID 20961076.

- ^ "Cloud Development". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2025-07-08.

- ^ Benmoshe, N.; Pinsky, M.; Pokrovsky, A.; Khain, A. (2012-03-27). "Turbulent effects on the microphysics and initiation of warm rain in deep convective clouds: 2-D simulations by a spectral mixed-phase microphysics cloud model". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 117 (D6) 2011JD016603. Bibcode:2012JGRD..117.6220B. doi:10.1029/2011JD016603. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Warm Rain Process". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Paul Sirvatka (2003). "Cloud Physics: Collision/Coalescence; The Bergeron Process". College of DuPage. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Alistair B. Fraser (15 January 2003). "Bad Meteorology: Raindrops are shaped like teardrops". Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2008.

- ^ a b c d Emmanuel Villermaux, Benjamin Bossa; Bossa (September 2009). "Single-drop fragmentation distribution of raindrops" (PDF). Nature Physics. 5 (9): 697–702. Bibcode:2009NatPh...5..697V. doi:10.1038/NPHYS1340. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2012.

- Victoria Gill (20 July 2009). "Why raindrops come in many sizes". BBC News.

- ^ United States Geological Survey (2009). "Are raindrops tear shaped?". United States Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Paul Rincon (16 July 2004). "Monster raindrops delight experts". British Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- ^ Norman W. Junker (2008). "An ingredients based methodology for forecasting precipitation associated with MCS's". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ a b c J. S. Oguntoyinbo & F. O. Akintola (1983). "Rainstorm characteristics affecting water availability for agriculture" (PDF). IAHS Publication Number 140. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Robert A. Houze Jr (October 1997). "Stratiform Precipitation in Regions of Convection: A Meteorological Paradox?" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 78 (10): 2179–2196. Bibcode:1997BAMS...78.2179H. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<2179:SPIROC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- ^ Marshall, J. S.; Palmer, W. M. (1948). "The distribution of raindrops with size". Journal of Meteorology. 5 (4): 165–166. Bibcode:1948JAtS....5..165M. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1948)005<0165:tdorws>2.0.co;2.

- ^ Houze Robert A.; Hobbs Peter V.; Herzegh Paul H.; Parsons David B. (1979). "Size Distributions of Precipitation Particles in Frontal Clouds". J. Atmos. Sci. 36 (1): 156–162. Bibcode:1979JAtS...36..156H. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1979)036<0156:SDOPPI>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Niu, Shengjie; Jia, Xingcan; Sang, Jianren; Liu, Xiaoli; Lu, Chunsong; Liu, Yangang (2010). "Distributions of Raindrop Sizes and Fall Velocities in a Semiarid Plateau Climate: Convective versus Stratiform Rains". J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 49 (4): 632–645. Bibcode:2010JApMC..49..632N. doi:10.1175/2009JAMC2208.1.

- ^ "Falling raindrops hit 5 to 20 mph speeds". USA Today. 19 December 2001. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ van der Westhuizen W.A.; Grobler N.J.; Loock J.C.; Tordiffe E.A.W. (1989). "Raindrop imprints in the Late Archaean-Early Proterozoic Ventersdorp Supergroup, South Africa". Sedimentary Geology. 61 (3–4): 303–309. Bibcode:1989SedG...61..303V. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(89)90064-X.

- ^ Som, Sanjoy M.; Catling, David C.; Harnmeijer, Jelte P.; Polivka, Peter M.; Buick, Roger (2012). "Air density 2.7 billion years ago limited to less than twice modern levels by fossil raindrop imprints". Nature. 484 (7394): 359–362. Bibcode:2012Natur.484..359S. doi:10.1038/nature10890. PMID 22456703. S2CID 4410348.

- ^ Prosperetti, Andrea & Oguz, Hasan N. (1993). "The impact of drops on liquid surfaces and the underwater noise of rain". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 25: 577–602. Bibcode:1993AnRFM..25..577P. doi:10.1146/annurev.fl.25.010193.003045.

- ^ Rankin, Ryan C. (June 2005). "Bubble Resonance". The Physics of Bubbles, Antibubbles, and all That. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

- ^ Alaska Air Flight Service Station (10 April 2007). "SA-METAR". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. 2000. ISBN 1-878220-34-9. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- ^ Fraser, Alistair B.; Bohren, Craig F. (1992). "Is Virga Rain That Evaporates before Reaching the Ground?". Monthly Weather Review. 120 (8): 1565–1571. Bibcode:1992MWRv..120.1565F. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1992)120<1565:IVRTEB>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0027-0644.

- ^ Karle, Nakul N.; Sakai, Ricardo K.; Fitzgerald, Rosa M.; Ichoku, Charles; Mercado, Fernando; Stockwell, William R. (2023-03-02). "Systematic analysis of virga and its impact on surface particulate matter observations". Atmospheric Measurement Techniques. 16 (4): 1073–1085. Bibcode:2023AMT....16.1073K. doi:10.5194/amt-16-1073-2023. ISSN 1867-1381.

- ^ Saini, Lekhraj; Das, Saurabh; Murukesh, Nuncio (2025-03-14). Virga Detection Tool based on Micro Rain Radar in Arctic (Report). Copernicus Meetings. doi:10.5194/egusphere-egu25-20517.

- ^ Jullien, Nicolas; Vignon, Étienne; Sprenger, Michael; Aemisegger, Franziska; Berne, Alexis (2020-05-27). "Synoptic conditions and atmospheric moisture pathways associated with virga and precipitation over coastal Adélie Land in Antarctica". The Cryosphere. 14 (5): 1685–1702. Bibcode:2020TCry...14.1685J. doi:10.5194/tc-14-1685-2020. hdl:20.500.11850/418970. ISSN 1994-0416.

- ^ "NASA Mars Lander Sees Falling Snow, Soil Data Suggest Liquid Past". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 2008-09-29. Retrieved 2023-12-14.

- ^ "Planet Venus: Earth's 'evil twin'". BBC News. 7 November 2005.

- ^ a b B. Geerts (2002). "Convective and stratiform rainfall in the tropics". University of Wyoming. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- ^ David Roth (2006). "Unified Surface Analysis Manual" (PDF). Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 September 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ MetEd (14 March 2003). "Precipitation Type Forecasts in the Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic states". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2010.

- ^ "Meso-Analyst Severe Weather Guide" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Robert Houze (October 1997). "Stratiform Precipitation in Regions of Convection: A Meteorological Paradox?". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 78 (10): 2179–2196. Bibcode:1997BAMS...78.2179H. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1997)078<2179:SPIROC>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Graupel". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Toby N. Carlson (1991). Mid-latitude Weather Systems. Routledge. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-04-551115-0.

- ^ "Mt Waialeale 1047, Hawaii (516565)". WRCC. NOAA. 1 August 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ^ Steven Businger and Thomas Birchard Jr. A Bow Echo and Severe Weather Associated with a Kona Low in Hawaii. Archived 17 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 22 May 2007.

- ^ Western Regional Climate Center (2002). "Climate of Hawaii". Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ^ a b Paul E. Lydolph (1985). The Climate of the Earth. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-86598-119-5.

- ^ Michael A. Mares (1999). Encyclopedia of Deserts. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8061-3146-7.

- ^ Adam Ganson (2003). "Geology of Death Valley". Indiana University. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Rainy season". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Costa Rica Guide (2005). "When to Travel to Costa Rica". ToucanGuides. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Michael Pidwirny (2008). "CHAPTER 9: Introduction to the Biosphere". PhysicalGeography.net. Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Elisabeth M. Benders-Hyde (2003). "World Climates". Blue Planet Biomes. Archived from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ Mei Zheng (2000). The sources and characteristics of atmospheric particulates during the wet and dry seasons in Hong Kong (PhD dissertation). University of Rhode Island. pp. 1–378. Bibcode:2000PhDT........13Z. ProQuest 304619312. Archived from the original on 17 February 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ S. I. Efe; F. E. Ogban; M. J. Horsfall; E. E. Akporhonor (2005). "Seasonal Variations of Physico-chemical Characteristics in Water Resources Quality in Western Niger Delta Region, Nigeria" (PDF). Journal of Applied Scientific Environmental Management. 9 (1): 191–195. ISSN 1119-8362. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2008.

- ^ C. D. Haynes; M. G. Ridpath; M. A. J. Williams (1991). Monsoonal Australia. Taylor & Francis. p. 90. ISBN 978-90-6191-638-3.

- ^ Chris Landsea (2007). "Subject: D3) Why do tropical cyclones' winds rotate counter-clockwise (clockwise) in the Northern (Southern) Hemisphere?". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Climate Prediction Center (2005). "2005 Tropical Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Outlook". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- ^ Jack Williams (17 May 2005). "Background: California's tropical storms". USA Today. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- ^ "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4)". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ R. S. Cerveny & R. C. Balling (6 August 1998). "Weekly cycles of air pollutants, precipitation and tropical cyclones in the coastal NW Atlantic region". Nature. 394 (6693): 561–563. Bibcode:1998Natur.394..561C. doi:10.1038/29043. S2CID 204999292.

- ^ Dale Fuchs (28 June 2005). "Spain goes hi-tech to beat drought". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 4 November 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- ^ Goddard Space Flight Center (18 June 2002). "NASA Satellite Confirms Urban Heat Islands Increase Rainfall Around Cities". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Climate Change Division (17 December 2008). "Precipitation and Storm Changes". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Central, Climate. "Heaviest Downpours Rise across the U.S". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ "Across U.S., Heaviest Downpours On The Rise | Climate Central". www.climatecentral.org. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- ^ American Meteorological Society (2 October 1998). "Planned and Inadvertent Weather Modification". Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Rainband. Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 24 December 2008.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Banded structure. Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 24 December 2008.

- ^ Owen Hertzman (1988). Three-Dimensional Kinematics of Rainbands in Midlatitude Cyclones. Retrieved on 24 December 2008

- ^ Yuh-Lang Lin (2007). Mesoscale Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-521-80875-0.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Prefrontal squall line. Archived 17 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 24 December 2008.

- ^ J. D. Doyle (1997). The influence of mesoscale orography on a coastal jet and rainband. Archived 6 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 December 2008.

- ^ A. Rodin (1995). Interaction of a cold front with a sea-breeze front numerical simulations. Archived 9 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 25 December 2008.

- ^ St. Louis University (4 August 2003). "What is a TROWAL? via the Internet Wayback Machine". Archived from the original on 16 September 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2006.

- ^ David R. Novak, Lance F. Bosart, Daniel Keyser, and Jeff S. Waldstreicher (2002). A Climatological and composite study of cold season banded precipitation in the Northeast United States. Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 December 2008.

- ^ Ivory J. Small (1999). An observation study of island effect bands: precipitation producers in Southern California. Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 December 2008.

- ^ University of Wisconsin–Madison (1998).Objective Dvorak Technique. Archived 10 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 29 May 2006.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Joan D. Willey; Bennett; Williams; Denne; Kornegay; Perlotto; Moore (January 1988). "Effect of storm type on rainwater composition in southeastern North Carolina". Environmental Science & Technology. 22 (1): 41–46. Bibcode:1988EnST...22...41W. doi:10.1021/es00166a003. PMID 22195508.

- ^ Joan D. Willey; Kieber; Avery (19 August 2006). "Changing Chemical Composition of Precipitation in Wilmington, North Carolina, U.S.A.: Implications for the Continental U.S.A". Environmental Science & Technology. 40 (18): 5675–5680. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.5675W. doi:10.1021/es060638w. PMID 17007125.

- ^ Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. (direct:Final Revised Paper Archived 3 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Kottek, Markus; Grieser, Jürgen; Beck, Christoph; Rudolf, Bruno; Rubel, Franz (2006-07-10). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated". Meteorologische Zeitschrift. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. ISSN 0941-2948.

- ^ Susan Woodward (29 October 1997). "Tropical Broadleaf Evergreen Forest: The Rainforest". Radford University. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ Susan Woodward (2 February 2005). "Tropical Savannas". Radford University. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Humid subtropical climate". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ Michael Ritter (24 December 2008). "Humid Subtropical Climate". University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Lauren Springer Ogden (2008). Plant-Driven Design. Timber Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-88192-877-8.

- ^ Michael Ritter (24 December 2008). "Mediterranean or Dry Summer Subtropical Climate". University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- ^ Brynn Schaffner & Kenneth Robinson (6 June 2003). "Steppe Climate". West Tisbury Elementary School. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Michael Ritter (24 December 2008). "Subarctic Climate". University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Archived from the original on 25 May 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Saxena, Vivek (2025). "Water Quality, Air Pollution, and Climate Change: Investigating the Environmental Impacts of Industrialization and Urbanization". Water, Air, & Soil Pollution. 236 (2) 73. Bibcode:2025WASP..236...73S. doi:10.1007/s11270-024-07702-4. ISSN 0049-6979.

- ^ Munoz G, Budzinski H, Babut M, Drouineau H, Lauzent M, Menach KL, et al. (August 2017). "Evidence for the Trophic Transfer of Perfluoroalkylated Substances in a Temperate Macrotidal Estuary" (PDF). Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (15): 8450–8459. Bibcode:2017EnST...51.8450M. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02399. PMID 28679050.

- ^ Ongetta, Stephan; Mohan Viswanathan, Prasanna; Mishra, Anshuman; Sabarathinam, Chidambaram (2025-05-17). "A Multiproxy Analysis of Rainwater Chemistry and Moisture Sources in Borneo". Earth Systems and Environment. Bibcode:2025ESE...tmp..112O. doi:10.1007/s41748-025-00653-8. ISSN 2509-9434.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bibcode (link) - ^ Gajewska, Magdalena; Fitobór, Karolina; Artichowicz, Wojciech; Ulańczyk, Rafał; Kida, Małgorzata; Kołecka, Katarzyna (2024-08-05). "Occurrence of specific pollutants in a mixture of sewage and rainwater from an urbanized area". Scientific Reports. 14 (1): 18119. Bibcode:2024NatSR..1418119G. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69099-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 11300779. PMID 39103480.

- ^ Cousins IT, Johansson JH, Salter ME, Sha B, Scheringer M (August 2022). "Outside the Safe Operating Space of a New Planetary Boundary for Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS)". Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (16). American Chemical Society: 11172–11179. Bibcode:2022EnST...5611172C. doi:10.1021/acs.est.2c02765. PMC 9387091. PMID 35916421.

- ^ Arp, Hans Peter H.; Gredelj, Andrea; Glüge, Juliane; Scheringer, Martin; Cousins, Ian T. (2024-11-12). "The Global Threat from the Irreversible Accumulation of Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA)". Environmental Science & Technology. 58 (45): 19925–19935. Bibcode:2024EnST...5819925A. doi:10.1021/acs.est.4c06189. ISSN 0013-936X. PMC 11562725. PMID 39475534.

- ^ Hanson, Mark L.; Madronich, Sasha; Solomon, Keith; Sulbaek Andersen, Mads P.; Wallington, Timothy J. (2024-10-01). "Trifluoroacetic Acid in the Environment: Consensus, Gaps, and Next Steps". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 43 (10): 2091–2093. Bibcode:2024EnvTC..43.2091H. doi:10.1002/etc.5963. ISSN 0730-7268. PMID 39078279.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (18 December 2021). "PFAS 'forever chemicals' constantly cycle through ground, air and water, study finds". The Guardian.

- ^ Sha B, Johansson JH, Tunved P, Bohlin-Nizzetto P, Cousins IT, Salter ME (January 2022). "Sea Spray Aerosol (SSA) as a Source of Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) to the Atmosphere: Field Evidence from Long-Term Air Monitoring". Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (1). American Chemical Society: 228–238. Bibcode:2022EnST...56..228S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c04277. PMC 8733926. PMID 34907779.

- ^ Sha, Bo; Johansson, Jana H.; Salter, Matthew E.; Blichner, Sara M.; Cousins, Ian T. (2024). "Constraining global transport of perfluoroalkyl acids on sea spray aerosol using field measurements". Science Advances. 10 (14) eadl1026. Bibcode:2024SciA...10L1026S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adl1026. PMC 10997204. PMID 38579007.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (August 2, 2022). "Pollution: 'Forever chemicals' in rainwater exceed safe levels". BBC News.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (2022-03-22). "'I don't know how we'll survive': the farmers facing ruin in America's 'forever chemicals' crisis". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-07-04.

- ^ Wang, Yuting; Gui, Jiang; Howe, Caitlin G.; Emond, Jennifer A.; Criswell, Rachel L.; Gallagher, Lisa G.; Huset, Carin A.; Peterson, Lisa A.; Botelho, Julianne Cook; Calafat, Antonia M.; Christensen, Brock; Karagas, Margaret R.; Romano, Megan E. (July 2024). "Association of diet with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in plasma and human milk in the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study". Science of the Total Environment. 933 173157. Bibcode:2024ScTEn.93373157W. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173157. ISSN 0048-9697. PMC 11247473. PMID 38740209.

- ^ Perkins, Tom (2024-07-04). "Coffee, eggs and white rice linked to higher levels of PFAS in human body". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-07-04.

- ^ Erdenesanaa, Delger (April 8, 2024). "PFAS 'Forever Chemicals' Are Pervasive in Water Worldwide". The New York Times.

- ^ "6. Measurement of Precipitation". Guide to Meteorological Instruments and Methods of Observation (WMO-No. 8) Vol. I Measurement of Meteorological Variables (Eighth ed.). World Meteorological Organization. 2024. p. 224.

- ^ "Chapter 5 – Principal Hazards in U.S.doc". p. 128. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Classroom Resources – Argonne National Laboratory". Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ "FAO.org". FAO.org. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- ^ Discovery School (2009). "Build Your Own Weather Station". Discovery Education. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Lehmann, Chris (2009). "2000 Reminders-4Q". Central Analytical Laboratory. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010.

- ^ National Weather Service (2009). "Glossary: W". Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ "Community Collaborative Rain, Hail & Snow Network Main Page". Colorado Climate Center. 2009. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ The Globe Program (2009). "Global Learning and Observations to Benefit the Environment Program". Archived from the original on 19 August 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ National Weather Service (2009). "NOAA's National Weather Service Main Page". Archived from the original on 1 January 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Kang-Tsung Chang, Jr-Chuan Huang; Shuh-Ji Kao & Shou-Hao Chiang (2009). "Radar Rainfall Estimates for Hydrologic and Landslide Modeling". Data Assimilation for Atmospheric, Oceanic and Hydrologic Applications. pp. 127–145. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-71056-1_6. ISBN 978-3-540-71056-1.

- ^ Eric Chay Ware (August 2005). "Corrections to Radar-Estimated Precipitation Using Observed Rain Gauge Data: A Thesis" (PDF). Cornell University. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ^ Pearl Mngadi; Petrus JM Visser & Elizabeth Ebert (October 2006). "Southern Africa Satellite Derived Rainfall Estimates Validation" (PDF). International Precipitation Working Group. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ a b Monjo, R. (2016). "Measure of rainfall time structure using the dimensionless n-index". Climate Research. 67 (1): 71–86. Bibcode:2016ClRes..67...71M. doi:10.3354/cr01359. (pdf) Archived 6 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Rain". Glossary of Meteorology. American Meteorological Society. June 2000. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ a b c Met Office (August 2007). "Fact Sheet No. 3: Water in the Atmosphere" (PDF). Crown Copyright. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ Panagos, Panos; Ballabio, Cristiano; Borrelli, Pasquale; Meusburger, Katrin; Klik, Andreas; Rousseva, Svetla; Tadić, Melita Perčec; Michaelides, Silas; Hrabalíková, Michaela; Olsen, Preben; Aalto, Juha; Lakatos, Mónika; Rymszewicz, Anna; Dumitrescu, Alexandru; Beguería, Santiago; Alewell, Christine (2015). "Rainfall erosivity in Europe". Science of the Total Environment. 511: 801–814. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.511..801P. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.01.008. hdl:10261/110151. PMID 25622150.

- ^ a b Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Return period". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 20 October 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). "Rainfall intensity return period". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Boulder Area Sustainability Information Network (2005). "What is a 100 year flood?". Boulder Community Network. Archived from the original on 19 February 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- ^ Jack S. Bushong (1999). "Quantitative Precipitation Forecast: Its Generation and Verification at the Southeast River Forecast Center" (PDF). University of Georgia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ Daniel Weygand (2008). "Optimizing Output From QPF Helper" (PDF). National Weather Service Western Region. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ Noreen O. Schwein (2009). "Optimization of quantitative precipitation forecast time horizons used in river forecasts". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2008.

- ^ Christian Keil; Andreas Röpnack; George C. Craig; Ulrich Schumann (31 December 2008). "Sensitivity of quantitative precipitation forecast to height dependent changes in humidity". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (9): L09812. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..35.9812K. doi:10.1029/2008GL033657. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- ^ Reggiani, P.; Weerts, A. H. (February 2008). "Probabilistic Quantitative Precipitation Forecast for Flood Prediction: An Application". Journal of Hydrometeorology. 9 (1): 76–95. Bibcode:2008JHyMe...9...76R. doi:10.1175/2007JHM858.1.

- ^ Charles Lin (2005). "Quantitative Precipitation Forecast (QPF) from Weather Prediction Models and Radar Nowcasts, and Atmospheric Hydrological Modelling for Flood Simulation" (PDF). Achieving Technological Innovation in Flood Forecasting Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ^ Bureau of Meteorology (2010). "Living With Drought". Commonwealth of Australia. Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Robert Burns (6 June 2007). "Texas Crop and Weather". Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ C., W. A. (1914). Briggs, L. J.; Shantz, H. L. (eds.). "The Water Requirement of Plants". The Plant World. 17 (3): 76–78. ISSN 0096-8307. JSTOR 43477376.

- ^ James D. Mauseth (7 July 2006). "Mauseth Research: Cacti". University of Texas. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Zhao, Xueyin; Chen, Mengting; Xie, Hua; Luo, Wanqi; Wei, Guangfei; Zheng, Shizong; Wu, Conglin; Khan, Shahbaz; Cui, Yuanlai; Luo, Yufeng (2023-04-30). "Analysis of irrigation demands of rice: Irrigation decision-making needs to consider future rainfall". Agricultural Water Management. 280 108196. Bibcode:2023AgWM..28008196Z. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108196. ISSN 0378-3774.

- ^ Feldman, Andrew F.; Feng, Xue; Felton, Andrew J.; Konings, Alexandra G.; Knapp, Alan K.; Biederman, Joel A.; Poulter, Benjamin (2024). "Plant responses to changing rainfall frequency and intensity". Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 5 (4): 276–294. Bibcode:2024NRvEE...5..276F. doi:10.1038/s43017-024-00534-0. ISSN 2662-138X.

- ^ A. Roberto Frisancho (1993). Human Adaptation and Accommodation. University of Michigan Press. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-472-09511-7.

- ^ Marti J. Van Liere; Eric-Alain D. Ategbo; Jan Hoorweg; Adel P. Den Hartog; Joseph G. A. J. Hautvast (1994). "The significance of socio-economic characteristics for adult seasonal body-weight fluctuations: a study in north-western Benin". British Journal of Nutrition. 72 (3): 479–488. doi:10.1079/BJN19940049. PMID 7947661.

- ^ Texas Department of Environmental Quality (16 January 2008). "Harvesting, Storing, and Treating Rainwater for Domestic Indoor Use" (PDF). Texas A&M University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (June 2000). "Flash Flood". American Meteorological Society. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ A. G. Barnston (10 December 1986). "The effect of weather on mood, productivity, and frequency of emotional crisis in a temperate continental climate". International Journal of Biometeorology. 32 (4): 134–143. Bibcode:1988IJBm...32..134B. doi:10.1007/BF01044907. PMID 3410582. S2CID 31850334.