Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

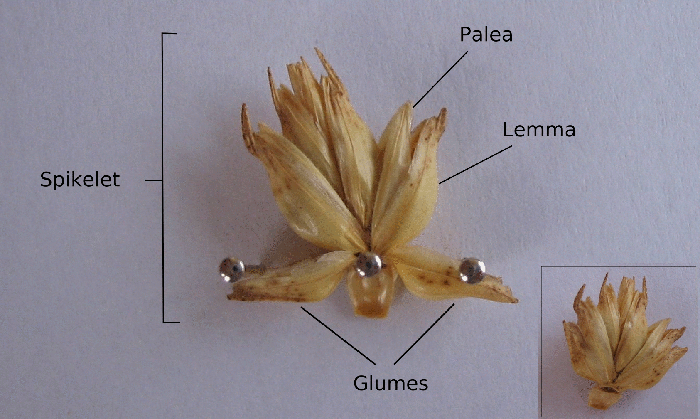

Spikelet

View on Wikipedia

A spikelet, in botany, describes the typical arrangement of the inflorescences of grasses, sedges and some other monocots.

Each spikelet has one or more florets.[1]: 12 The spikelets are further grouped into panicles or spikes. The part of the spikelet that bears the florets is called the rachilla.[1]: 13

In grasses

[edit]In Poaceae, the grass family, a spikelet consists of two (or sometimes fewer) bracts at the base, called glumes, followed by one or more florets.[1]: 13 A floret consists of the flower surrounded by two bracts, one external (the lemma) and one internal (the palea). The perianth is reduced to two scales, called lodicules,[1]: 11 that expand and contract to spread the lemma and palea; these are generally interpreted to be modified sepals.

The flowers are usually hermaphroditic — maize being an important exception — and mainly anemophilous or wind-pollinated, although insects occasionally play a role.[2]

Lemma

[edit]Lemma is a phytomorphological term referring to a part of the spikelet. It is the lowermost of two chaff-like bracts enclosing the grass floret. The lemma often bears a long bristle called an awn, and may be similar in form to the glumes, which are chaffy bracts at the base of each spikelet. It is usually interpreted as a bract but it has also been interpreted as one remnant (the abaxial) of the three members of outer perianth whorl (the palea may represent the other two members, having been joined together).

The lemmas' shape, their number of veins, whether they are awned or not, and the presence or absence of hairs are particularly important characters in grass taxonomy.

Palea

[edit]Palea, in Poaceae, refers to one of the bract-like organs in the spikelet.

The palea is the uppermost of the two chaff-like bracts that enclose the grass floret (the other being the lemma). It is often cleft at the tip, implying that it may be a double structure derived from the union of two separate organs. This has led to suggestions that it may be what remains of the grass sepals (outer perianth whorl): specifically the two adaxial members of the three membered whorl typical of monocots. The third member may be absent or it may be represented by the lemma, according to different botanical interpretations.

The perianth interpretation of the palea is supported by the expression of MADS-box genes in this organ during development, as is the case in sepals of eudicot plants.[3]

Lodicule

[edit]A lodicule is the structure that consists of between one and three small scales at the base of the ovary in a grass flower that represent the corolla, believed to be a rudimentary perianth. The swelling of the lodicules forces apart the flower's bracts, exposing the flower's reproductive organs.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Cope, T.; Gray, A. (30 October 2009). Grasses of the British Isles. London, U.K.: Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland. ISBN 9780901158420.

- ^ "Insect Pollination of Grasses". Australian Journal of Entomology. 3: 74. 1964. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.1964.tb00625.x.

- ^ Prasad, K, et al. (2005) OsMADS1, a rice MADS-box factor, controls differentiation of specific cell types in the lemma and palea and is an early-acting regulator of inner floral organs. The Plant Journal 43, 915–928

Spikelet

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Occurrence

Definition

A spikelet is defined as the fundamental unit of the inflorescence in the Poaceae (grass family) and Cyperaceae (sedge family), consisting of a short axis (rachilla) bearing two basal sterile bracts known as glumes, which subtend one or more florets—each floret comprising a small, typically wind-pollinated flower enclosed by additional bracts (lemma and palea).[5][6] In these monocot families, the spikelet functions as both a morphological and reproductive module, aggregating florets into a compact, spike-like cluster that facilitates efficient pollination and seed production within diverse inflorescence architectures such as spikes, racemes, or panicles.[7] The term "spikelet" derives from the Latin spica, meaning "ear of grain" or "spike," combined with the English diminutive suffix "-let," emphasizing its resemblance to a miniature spike of florets adapted for compact arrangement in wind-exposed environments.[8] This nomenclature reflects the structure's evolutionary adaptation in open habitats, where the enclosed florets are protected yet positioned for airborne pollen transfer.[7] As the primary reproductive unit, the spikelet houses bisexual or unisexual florets optimized for anemophily (wind pollination), with features like feathery stigmas and exposed anthers that promote cross-pollination and subsequent seed dispersal, often via the entire spikelet detaching as a disseminule.[7] This design enhances survival in grassland ecosystems by minimizing reliance on animal vectors and maximizing efficiency in pollen and seed distribution.[5]Occurrence in Plant Families

Spikelets are a characteristic inflorescence unit predominantly found in the Poaceae family (grasses), which encompasses approximately 11,800 accepted species across 790 genera, making it one of the largest families of flowering plants.[9] They are also prevalent in the Cyperaceae (sedges), comprising about 5,600 species in 109 genera, and the Juncaceae (rushes), with approximately 440 species in 8 genera.[10] Additionally, spikelets occur in the Restionaceae, a family of roughly 570 species primarily distributed in southern Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, where they form part of wind-pollinated inflorescences. In Juncaceae, spikelets typically feature six perianth segments, differing from the glume-enclosed florets in Poaceae.[11][12][13] Phylogenetically, spikelets are a defining feature of commelinid monocots within the order Poales, evolving from ancestral branched inflorescences through reductions and specializations that facilitated compact, efficient reproductive units.[14] This innovation arose early in Poales diversification, with homologous structures evident in basal families like Rapateaceae, but absent in eudicots and basal angiosperms, underscoring their monocot-specific adaptation.[15] Ecologically, spikelets evolved in open, windy environments to support anemophily (wind pollination), enabling efficient pollen transfer in grasses across diverse biomes from prairies to savannas.[16] In Cyperaceae, particularly sedges like those in the genus Carex, spikelets dominate wetland and marsh ecosystems, where their compact form aids in seed dispersal via water or wind amid high humidity.[6] This distribution highlights spikelets' adaptive significance in grassland and aquatic habitats, with examples including their ubiquity in cereal crops such as wheat (Triticum aestivum) and rice (Oryza sativa) in Poaceae, where they form the basis of grain production.[15]Structure in Grasses (Poaceae)

Overall Organization

The spikelet represents the fundamental unit of the inflorescence in the grass family (Poaceae), characterized by a short central axis called the rachilla that bears one or more florets, typically flanked by one to two basal sterile glumes. This hierarchical structure distinguishes spikelets as specialized, short-lived branches that aggregate into larger compound inflorescences, such as spikes, racemes, or panicles, enabling efficient reproductive organization unique to grasses.[15][17] The rachilla functions as the supportive axis within the spikelet, either elongated to accommodate sequential florets or abbreviated in more compact forms, and it may continue beyond the uppermost floret to form an extension or terminate abruptly at the apex. Florets are positioned along the rachilla in an alternate or opposite arrangement, each arising as a lateral unit subtended by a lemma, with florets generally bisexual in most species but unisexual in others, such as those exhibiting dioecy. The glumes act as basal bracts that enclose the lower portion of the rachilla and its initial florets.[15][5][18] In many grass species, the entire spikelet serves as the primary dispersal unit, or disseminule, which detaches intact to aid in seed propagation through mechanisms like wind dispersal or adhesion to animals, thereby enhancing the plant's reproductive success across diverse habitats.[19][20]Glumes and Rachilla

In grass spikelets, glumes are the sterile basal bracts that subtend the florets, typically numbering one or two and consisting of membranous or hyaline tissue that is often keeled along the midline.[17][21] These glumes lack flowers and are usually veinless or bear only a few prominent veins, with the lower glume frequently larger and more persistent than the upper one.[17][22] Their primary functions include protecting the developing florets from environmental stresses and facilitating spikelet disarticulation during seed dispersal, as they form part of the dispersal unit when fracture occurs below or above them.[21][22] Variations in glume number and form occur across Poaceae tribes; for instance, many species have two glumes.[18][17] In certain genera like Aristida (tribe Aristideae), the glumes are awned, bearing prominent awns that aid in attachment to animal fur or soil for dispersal, while in others they remain unawned and glossy or dull in texture.[17][22] The rachilla serves as the continuous or disarticulating central axis of the spikelet, positioned between the glumes and florets, with short internodes that support the distichous arrangement of florets.[17][21] It often exhibits a zig-zag course and may bear callus hairs at the internodes or floret bases to enhance attachment and stability during development.[17][22] Functionally, the rachilla provides structural support for the florets and contributes to disarticulation patterns, remaining attached to the palea side in some species after floret separation.[22][21] Variations include hairy rachillae in tribes like Stipeae, where hairs measure 2-3 mm, contrasting with glabrous or short-haired forms in others, and prolongation beyond the distal floret in Poeae.[17]Floret Components

In grasses (Poaceae), the floret represents the individual flower unit within a spikelet, comprising the lemma, palea, lodicules, androecium, and gynoecium.[23] Typically, a spikelet contains 1 to several florets, varying by species and serving as a key taxonomic feature.[24] These florets attach sequentially to the rachilla, the central axis of the spikelet.[25] The general arrangement positions each floret enclosed by its lemma and palea, which function as protective bracts, while the lodicules serve as a reduced perianth that aids in flower opening during anthesis.[23] Most florets are perfect, or bisexual, bearing both stamens and a pistil, though unisexual florets occur in certain species, such as maize (Zea mays), where male (staminate) and female (pistillate) florets develop in separate inflorescences on the same plant. Development follows a basipetal sequence, with basal florets typically fertile and functional, while upper florets often become reduced to sterile rudiments lacking viable reproductive organs.[26] Maturation thus proceeds from the base toward the tip of the spikelet, ensuring progressive seed development. Collectively, the florets form the fertile core of the spikelet, with overlapping lemmas providing mutual enclosure and protection against environmental stresses.[23] This organization enhances the spikelet's efficiency in pollination and seed dispersal within wind-pollinated grass inflorescences.[25]Lemma

The lemma serves as the outermost fertile bract subtending the floret in grass (Poaceae) spikelets, functioning as a protective structure that encloses the inner palea and reproductive organs.[26] Morphologically, it is typically boat-shaped or hooded, with 3–9 parallel veins running longitudinally; the margins are often inrolled, and the apex varies from acute to truncate or bifid, contributing to its rigid, leaf-like form.[27][28][29][30] Awns, when present, arise as extensions primarily from the apex (terminal), the back (intermediate), or rarely the base of the lemma, providing mechanical protection against herbivores or facilitating seed dispersal.[31] For instance, the long, hygroscopically responsive awns of wild wheat (Triticum dicoccoides) twist and untwist with moisture changes, enabling the dispersal unit to drill into soil for burial and establishment.[32] Beyond protection and dispersal, the lemma aids pollination by flexing open in coordination with lodicule swelling to expose anthers and stigmas, while its vein patterns, awn presence, and apex shape are critical diagnostic traits for species identification in grass taxonomy.[26][33] Developmentally, the lemma originates from leaf-like primordia in the floral meristem, evolving as a specialized bract that contrasts with sterile lemmas in multi-floret spikelets, where lower lemmas may be reduced or lack enclosed reproductive structures.[34][15] This distinction highlights the lemma's role in floret fertility, with fertile lemmas maintaining vascular connections to support the enclosed flower.[18]Palea

The palea is the inner bract of a grass floret in the Poaceae family, forming a membranous, scale-like structure positioned behind the lemma and closest to the rachilla axis. It typically features two prominent veins flanked by keels, which provide structural support, and is often shorter than the lemma with an apex that is rounded or acute depending on the species. This delicate texture contrasts with the firmer lemma, making the palea more translucent and less robust in enclosing the floret's contents.[18][35][18] In terms of attachment, the palea is generally adnate to the rachilla at its base, though it can be free-standing in certain taxa, and it frequently persists with the mature caryopsis. Variations include the presence of dorsal wings or pubescence, such as short, coarse hairs along the keels in species like Poa pratensis, which may aid in dispersal or protection. These features contribute to its role in multi-floret spikelets, where paleas of lower florets can be comparatively larger to accommodate developing structures.[5][36][21] The primary function of the palea is to protect the ovary and stamens within the floret, forming a close-fitting enclosure with the lemma that safeguards against physical damage, pathogens, and insects. It also facilitates floret closure by interlocking with the lemma margins, which opens upon lodicule swelling to expose reproductive organs during anthesis. In some unisexual florets, the palea may be reduced or absent, as observed in genera like Agrostis, adapting to specific reproductive strategies. Additionally, the palea contributes photosynthetic products to developing seeds in early stages, influencing grain size and quality.[37][38][26][5][39]Lodicules

Lodicules are the reduced perianth structures in grass (Poaceae) florets, consisting of 2–3 small, fleshy, transparent scales positioned at the base of the floret between the lemma and the ovary.[40] The anterior two lodicules are typically larger and more prominent, while the posterior one is often vestigial or absent; in some cases, lodicules may be entirely absent or number up to 6 in primitive or specialized taxa.[41] Morphologically, they are peltate-ascidiate phyllomes, varying in shape from ovate to lanceolate across subfamilies, with features such as ciliation, veining, and vascularization that differ between groups like Panicoideae (often split distally) and Pooideae (with dorsal wings).[42] The primary function of lodicules is hygroscopic, enabling them to swell rapidly upon water absorption at floret maturity, which forces the lemma and palea apart to expose the stamens and stigmas for anemophilous (wind-mediated) pollination.[40] Post-anthesis, the lodicules dry and contract, closing the floret to protect the developing seed.[43] This dynamic movement is crucial for the mating system in grasses, ranging from autogamy to allogamy depending on lodicule development.[44] Variations in lodicules occur across grass species, particularly in relation to reproductive strategies; they are often reduced in size or completely absent in cleistogamous (self-pollinating) grasses, where florets remain closed to promote autogamy without external exposure.[43] In bamboos and certain temperate woody bamboos, lodicules may number 3 or more and exhibit distinct ciliate or membranous traits adapted to their inflorescence types.[41] Evolutionarily, lodicules are homologous to the sepals and petals of other angiosperm flowers, representing a derived perianth reduction that supports the transition to wind pollination as a key adaptation in the Poaceae family.[45] This homology is evident in their genetic similarities to inner perianth whorls in other monocots and their role in floral organ identity.[46]Reproductive Organs

The reproductive organs of grass spikelets are housed within the florets and consist of a standardized androecium and gynoecium adapted for efficient wind-mediated seed production. The androecium typically comprises three stamens, each featuring a linear filament and a versatile, bilocular anther, which dehisces longitudinally to release pollen.[47][48] These anthers are pendulous, facilitating the shedding of lightweight pollen grains in large, wind-dispersed clouds characteristic of anemophilous pollination.[49] The gynoecium forms a single pistil with a superior ovary that is unilocular (appearing monocarpellary despite its tricarpellary origin), containing a single basal ovule on axile placentation.[45][50] This structure elongates into three free styles, each bearing a feathery stigma designed to capture airborne pollen efficiently.[45] Following fertilization, the ovule develops into a caryopsis, a dry, indehiscent fruit where the seed coat fuses with the pericarp, enclosing the embryo and starchy endosperm essential for grass propagation.[50][51] Pollination in grass florets is predominantly anemophilous, with self-pollination or cross-pollination occurring depending on species-specific traits like protandry or synchrony in anther and stigma emergence; apomixis, an asexual seed formation bypassing fertilization, is observed in certain genera such as Poa, enhancing reproductive assurance in variable environments.[49][52] In many spikelets, particularly those with multiple florets, the upper florets are often staminate (male-only, with functional anthers but no pistil) or pistillate (female-only, with a functional gynoecium but reduced or absent stamens), or entirely sterile, which optimizes resource allocation by minimizing energy expenditure on non-viable reproductive efforts.[5][18] This functional dimorphism contributes to the family's ecological success across diverse habitats.[5]Variations in Grasses

Classification by Floret Number

Grass spikelets are classified based on the number of florets they contain and the fertility patterns of those florets, reflecting diverse reproductive strategies within the Poaceae family. This classification highlights adaptations ranging from single-fertile-floret units optimized for rapid seed production to complex multi-floret structures that maximize pollination opportunities. Such variations occur primarily in grasses, where floret number influences disarticulation, dispersal, and environmental resilience.[53] One-flowered spikelets feature a single fertile floret, typically enclosed by two glumes, with the rachilla often absent or reduced to a short extension. This configuration is prevalent in the subfamily Chloridoideae, such as in Cynodon dactylon (bermudagrass), where each spikelet contains exactly one floret to facilitate efficient seed set in resource-limited conditions. The simplicity of this structure minimizes energy investment per inflorescence unit.[54][55][53] Multi-flowered spikelets, in contrast, contain 2 to more than 20 florets per unit, with the basal florets usually fertile and upper ones progressively reduced or sterile. In the subfamily Pooideae, exemplified by wheat (Triticum aestivum), spikelets typically bear 4–6 florets, enabling higher potential grain yield through sequential development along an elongating rachilla. Some grasses exhibit cleistogamous variants of multi-flowered spikelets, where florets are enclosed within sheaths for self-pollination, as seen in certain Pooideae species, promoting reproduction in low-pollen environments.[56][57][58] Unisexual spikelets represent a specialized case, comprising either staminate (male) or pistillate (female) florets exclusively, often segregated into distinct inflorescences. In the tribe Andropogoneae, such as maize (Zea mays), tassel spikelets are staminate with two florets per unit, while ear spikelets are pistillate with one floret, supporting monoecious reproduction and cross-pollination. This dimorphism enhances genetic diversity in wind-pollinated systems.[59][60] Evolutionary trends in grass spikelets show a reduction from multi-flowered ancestral forms to single-flowered states in arid-adapted lineages, particularly within Chloridoideae, to optimize reproductive efficiency under water stress by streamlining floret investment and dispersal. This shift correlates with the adoption of C4 photosynthesis and xeric habitats, reducing competition among florets for limited resources.[53][61][62]Classification by Compression and Inflorescence Type

Grass spikelets in the Poaceae family are classified by their compression, which refers to the shape in cross-section and influences their orientation and function within the inflorescence. Laterally compressed spikelets, flattened from side to side, predominate in subfamilies such as Pooideae (e.g., Festuca and Agrostis), where the lemmas and palea overlap laterally for protection. Dorsally compressed spikelets, flattened from back to front, are characteristic of many Panicoideae members like Setaria and Paspalum, allowing for a more compact arrangement that exposes the florets dorsally. Terete spikelets, which are cylindrical or round in cross-section, occur in certain Bambusoideae (e.g., Bambusa) and Aristidoideae (e.g., Aristida), providing structural rigidity in woody or specialized grasses.[23] Inflorescence types further classify spikelets based on their attachment and aggregation. In spikes, spikelets are sessile, directly attached to an unbranched rachis, as seen in Triticeae grasses like wheat (Triticum aestivum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare), facilitating efficient wind pollination in dense arrays. Racemes feature pedicellate spikelets borne singly along an unbranched axis, while panicles involve branching with pedicellate spikelets, common in Aveneae (e.g., oats, Avena sativa) for broader dispersal in open environments. Dimorphic arrangements, where spikelets occur in pairs—one sessile and fertile, the other pedicellate and often sterile—appear in some genera of Panicoideae, such as Andropogon (Andropogoneae), enhancing reproductive efficiency by protecting the fertile unit. Glume shapes, such as keeled in laterally compressed forms, are influenced by these compression types to support rachilla stability.[23] Spikelets are also distinguished as awned or awnless, impacting seed dispersal mechanisms. Awned spikelets bear a bristle-like extension from the lemma, as in barley (Hordeum vulgare) and needlegrasses (Stipa spp.), where the awn twists and hygroscopically moves to aid soil burial and animal-mediated dispersal. Awnless spikelets, prevalent in crops like rice (Oryza sativa) and some forage grasses (e.g., Festuca), lack this projection, reducing shattering for easier human harvest in domesticated varieties. These traits reflect selective pressures, with awns providing adaptive advantages in natural settings for seed establishment, while their absence in agriculture minimizes losses during threshing.[23][31] The classification by compression and inflorescence type holds adaptive significance tied to environmental interactions. Lateral compression in Pooideae grasses optimizes wind exposure for temperate, open habitats, while dorsal compression in Panicoideae supports C4 photosynthesis efficiency in warmer, arid regions by minimizing surface area. Panicle arrangements allow flexible branching for variable wind conditions, enhancing pollen transfer compared to rigid spikes in stable environments. Awns contribute to dispersal success, with studies showing improved germination in heat-stressed conditions for awned forms, underscoring their role in grass diversification across biomes.[23][63][64]Spikelets in Other Families

In Cyperaceae (Sedges)

In the Cyperaceae family, commonly known as sedges, spikelets differ markedly from those in grasses by often featuring unisexual flowers in many species, subtended solely by glumes, without lemmas or paleas, reflecting adaptations to wetland environments where these plants predominate.[6] Each spikelet comprises an indeterminate rachilla bearing spirally or distichously arranged glumes, with each glume subtending a single flower that may be bisexual or unisexual (male or female).[6] Male flowers typically contain 1–3 stamens, while female flowers possess a tricarpellate ovary that develops into an achene fruit.[65] Unlike grass spikelets, which include bisexual florets protected by dual bracts (lemma and palea), sedge spikelets also feature an indeterminate rachilla but rely on glumes alone for enclosure of individual flowers, aligning with the family's solid, triangular stems.[6][66] Spikelet arrangements in sedges vary but commonly form terminal or lateral spikes on the inflorescence, with sexual separation enhancing wind pollination in moist habitats.[66] Many species display distinct male and female spikes, with male spikes positioned uppermost for pollen dispersal and female spikes lower for seed maturation.[67] For instance, in the genus Carex, inflorescences consist of 2–20 spikelets aggregated into spikes, where female spikelets are often pendulous and enclosed in inflated perigynia for protection in damp conditions.[67][68] In contrast, genera like Scirpus feature dense, head-like clusters of spikelets in compact inflorescences, facilitating efficient reproduction in aquatic or marshy settings.[69] These configurations underscore sedges' divergence from grasses, emphasizing unisexuality in certain lineages and glume-based simplicity over floret complexity.[6]In Juncaceae and Restiaceae

In the Juncaceae family, commonly known as rushes, spikelet-like structures consist of compact inflorescences bearing multiple bisexual flowers, each subtended by a bract and featuring a perianth of six tepals arranged in two whorls of three. These flowers typically include six stamens, arranged in two whorls opposite the tepals, and a superior, three-carpellate ovary that develops into a loculicidal capsule containing numerous seeds. Spikelets are often arranged in terminal or lateral heads or diffuse panicles, with species in the genus Juncus exhibiting 10–100 flowers per spikelet, contributing to the family's adaptation to wetland habitats.[70][71][72] The Restiaceae, or restiads, display similar spikelet structures but with notable reductions, particularly in female flowers, which are mostly unisexual and dioecious, featuring a perianth of three functional tepals and three staminodes derived from the inner whorl. Male flowers have three fertile stamens opposite the tepals, while the ovary in females is superior, one- to three-locular, with feathery styles and maturing into a capsule. Spikelets are aggregated in spikes, heads, or panicles, often with an elongated rachilla as seen in Restio species, and are adapted to nutrient-poor, fire-prone ecosystems like the South African fynbos.[73][74][75] Both families share primitive monocot traits, including colorful or hyaline tepals that aid in pollinator attraction or protection, contrasting with the reduced or absent perianth in more derived Poaceae and Cyperaceae. These spikelets represent transitional forms from ancestral racemose inflorescences, retaining a perianth-bearing condition typical of basal commelinids. Phylogenetically, Juncaceae occupies a position in the cyperid clade of Poales, sister to Cyperaceae, while Restiaceae forms part of the restiid clade basal to the graminid clade containing Poaceae, underscoring their earlier divergence within the order.[76][77]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/spikelet