Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Perianth

View on Wikipedia

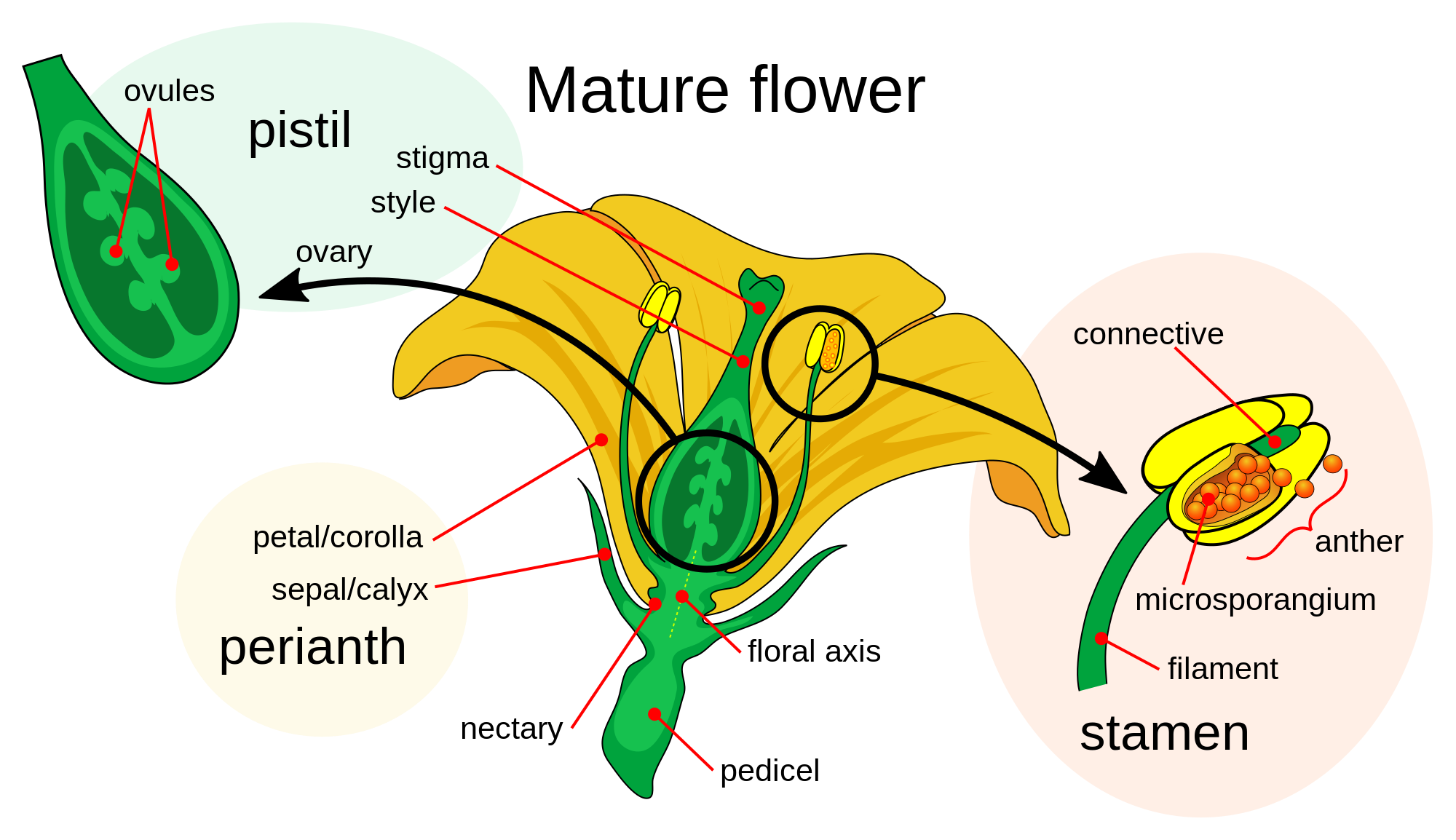

The perianth (perigonium, perigon or perigone in monocots) is the non-reproductive part of a flower. It is a structure consisting of the calyx (sepals) and the corolla (petals); in perigones it consists of the tepals. It forms an envelope surrounding the sexual organs,. The term perianth is derived from Greek περί (peri, "around") and άνθος (anthos, "flower"), while perigonium is derived from περί (peri) and γόνος (gonos, "seed, sex organs"). In the mosses and liverworts (Marchantiophyta), the perianth is the sterile (neither male nor female) tube-like tissue that surrounds the female reproductive structure or developing sporophyte.

Flowering plants

[edit]In flowering plants, the perianth may be described as being either dichlamydeous/heterochlamydeous in which the calyx and corolla are clearly separate, or homochlamydeous, in which they are indistinguishable (and the sepals and petals are collectively referred to as tepals). When the perianth is in two whorls, it is described as biseriate. While the calyx may be green, known as sepaloid, it may also be brightly coloured, and is then described as petaloid. When the undifferentiated tepals resemble petals, they are also referred to as "petaloid", as in petaloid monocots or liliod monocots, orders of monocots with brightly coloured tepals. The corolla and petals have a role in attracting pollinators, but this may be augmented by more specialised structures like the corona (see below).

When the perianth consists of separate tepals the term apotepalous is used, or syntepalous if the tepals are fused to one another. The petals may be united to form a tubular corolla (gamopetalous or sympetalous). If either the petals or sepals are entirely absent, the perianth can be described as being monochlamydeous.

-

Achlamydeous floral meristem without a corolla or calyx

-

Monochlamydeous perianth with non-petaloid calyx only

-

Monochlamydeous perianth with corolla only or homochlamydeous perigonium with tepals

-

Dichlamydeous/heterochlamydeous perianth with separate whorls

Both sepals and petals may have stomata and veins, even if vestigial. In some taxa, for instance some magnolias and water lilies, the perianth is arranged in a spiral on nodes, rather than whorls. Flowers with spiral perianths tend to also be those with undifferentiated perianths.

Corona

[edit]

A. inferior ovary

B. The calyx is a crown-shaped pappus, called a corona.

C. Anthers are united in a tube around the style, though the filaments are separate.

D. A ligulate petal extends from the tubular corolla.

E. style and stigmas

An additional structure in some plants (e.g. Narcissus, Passiflora (passion flower), some Hippeastrum, Liliaceae) is the corona (paraperigonium, paraperigon, or paracorolla), a ring or set of appendages of adaxial tissue arising from the corolla or the outer edge of the stamens. It is often positioned where the corolla lobes arise from the corolla tube.[1] There can be more than one corona in a flower. The milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) have three very different coronas, which collectively form a flytrap pollination scheme. Some passionflowers (Passiflora spp.) have as many as eight coronas arranged in concentric whorls.[2][3]

The pappus of Asteraceae, considered to be a modified calyx, is also called a corona if it is shaped like a crown.[1]

-

Flower of Narcissus showing an outer white corolla with a central yellow corona (paraperigonium)

-

Flower of Passiflora incarnata showing corona of fine appendages between petals and stamens

References

[edit]- ^ a b Beentje, H.; Williamson, J. (2010). The Kew Plant Glossary: an Illustrated Dictionary of Plant Terms. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Kew Publishing.

- ^ Lawrence, George H.M. (1951). Taxonomy of Vascular Plants. New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 616.

- ^ Engler and Prantl Naturlichen Pflanzenfamilian Band 21 page 503 (figure 232b)

Bibliography

[edit]- Simpson, Michael G. (2011). Plant Systematics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-051404-8. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

External links

[edit]Perianth

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Etymology

The term "perianth" derives from the Modern Latin perianthium, coined in the 17th century to describe the envelope surrounding a flower, literally combining the Greek prefix peri- meaning "around" with anthos meaning "flower".[8] This neologism was first employed in botanical nomenclature during the 18th century by Carl Linnaeus, who used perianthium specifically to denote the calyx in his classifications of floral parts, as seen in works such as Philosophia Botanica (1751) and descriptions of species like Gratiola, where he described it as "Perianthium quinquepartitum, erectum".[9] An alternative etymological interpretation appears in the related term perigonium (or perigone), which emphasizes the structure's role in enclosing reproductive organs and derives from Greek peri- "around" and gonos "seed" or "progeny".[10] This variant highlights the protective enclosure of sexual structures, contrasting slightly with the flower-focused perianthium. The term entered English botany through the French périanthe, with the earliest recorded English usage in 1785 by botanist Thomas Martyn in a translation of a botanical text, marking its adoption in the late 18th century before wider use in 19th-century English botanical literature.[11] This linguistic evolution relates to modern terms like calyx and corolla, which denote specific components of the perianth.Basic Components

The perianth serves as the sterile outer envelope of a flower, enclosing and protecting the reproductive organs in its early stages of development. In dichlamydeous flowers, it comprises two distinct whorls: the outer calyx, formed by sepals that are typically green and leaf-like, and the inner corolla, composed of petals that are often colorful and showy. This structure is characteristic of many angiosperms, where the calyx provides mechanical protection while the corolla aids in visual attraction, though both are non-reproductive.[6][12] Perianth arrangements are classified as biseriate or uniseriate based on the number of whorls. A biseriate perianth features two whorls—the calyx and corolla—arranged in series around the flower's axis, with sepals and petals alternating or opposite each other. In contrast, a uniseriate perianth consists of a single whorl, often undifferentiated into sepals and petals, resulting in a more simplified envelope. This distinction highlights evolutionary variations in floral morphology, with biseriate forms predominant in core eudicots.[6][12] The fusion states of perianth parts further describe their anatomical configuration. In apotepalous conditions, the individual sepals or petals remain free and separate from one another, allowing independent movement. Conversely, syntepalous (for tepals) or gamopetalous (for petals) arrangements involve fusion of these parts, forming a tube or bell-shaped structure that can enhance durability or pollination efficiency. Basic diagrams of perianth structure typically illustrate these components as concentric whorls surrounding the inner androecium (stamens) and gynoecium (carpels), with lines or shading denoting free versus fused segments—for example, in a tulip (biseriate, apotepalous) versus a morning glory (biseriate, gamopetalous).[13][14]Structure in Flowering Plants

Calyx and Corolla

In most angiosperms, particularly eudicots, the perianth is differentiated into two distinct whorls: the outer calyx and the inner corolla. The calyx consists of sepals, which are typically green, leaf-like structures that form the outermost protective layer of the flower bud. These sepals enclose and shield the developing flower from environmental damage, desiccation, and herbivores before anthesis, while often remaining photosynthetic post-opening. For instance, in roses (Rosa spp.), the five sepals are free or slightly connate at the base, providing a persistent protective envelope around the fruit (hip) after petal abscission. The corolla comprises the inner whorl of petals, which are usually more delicate, brightly colored, and non-photosynthetic, serving primarily aesthetic roles in pollinator attraction. Petals exhibit diverse morphologies, including radial (actinomorphic) symmetry, where the flower can be divided into mirror images along multiple planes, as seen in many eudicots like sunflowers, or bilateral (zygomorphic) symmetry, with a single plane of reflection, common in specialized pollination syndromes such as those in snapdragons. This differentiation into calyx and corolla represents the dichlamydeous condition, prevalent in eudicots including families like Brassicaceae (e.g., cabbage) and Solanaceae (e.g., tomato), where the sepals and petals are morphologically and functionally distinct. Variations in fusion occur within these whorls; for example, a gamosepalous calyx features sepals united at least basally into a tube or cup, as in many Solanaceae species where the five sepals form a persistent structure that aids fruit protection. Such fusions enhance structural integrity and can influence pollination mechanics, though polysepalous (free) sepals predominate in basal eudicots. The calyx and corolla are believed to have originated from modified leaf-like structures in early angiosperm ancestors, with sepals retaining more foliar traits and petals evolving specialized pigmentation and nectar guides. Fossil evidence from Early Cretaceous deposits, around 130 million years ago, shows primitive flowers with undifferentiated or minimally differentiated perianths, lacking clear calyx-corolla division, suggesting this specialization arose through subsequent evolutionary refinement in core eudicots.Tepals

Tepals are the undifferentiated segments of the perianth in homochlamydeous flowers, where the calyx and corolla are not distinctly separated, resulting in a uniform envelope of similar floral organs.[13] These flowers are characteristic of many monocots, such as tulips (Tulipa spp.) and lilies (Lilium spp.), as well as basal angiosperms like magnolias (Magnolia spp.), where the perianth consists of multiple whorls or spirals of tepals that are often petaloid in appearance.[15][16] In these taxa, tepals serve as the primary perianth structures, blending sepal-like and petal-like traits without clear morphological boundaries between outer and inner whorls.[17] The arrangement of tepals varies phylogenetically, often occurring in spirals or whorls. In basal angiosperms such as water lilies (Nymphaea spp.), tepals are arranged spirally around the receptacle, reflecting an ancestral condition with gradual transitions between perianth and reproductive organs.[13] Conversely, in petaloid monocots like orchids (Orchidaceae), tepals form two whorls of three, with the outer whorl comprising sepals and the inner featuring petals, though all may appear similarly colored and textured due to shared developmental cues.[18] Adaptations in tepal morphology emphasize color and texture to enhance visual appeal, particularly in petaloid forms. For instance, in wind-pollinated grasses (Poaceae), the perianth is reduced, with two or three lodicules—modified, scale-like structures homologous to petals—exhibiting petaloid characteristics that swell to expose reproductive parts during anthesis.[19][20] These lodicules, positioned adjacent to stamens, represent a derived adaptation where subtle coloration and hygroscopic movement facilitate pollination without prominent display.[21] Developmentally, tepal formation in homochlamydeous flowers aligns with modifications to the ABC model of floral organ identity, where class A genes (e.g., APETALA1 and APETALA2 homologs) predominate in the outer perianth without strict B-class differentiation, yielding uniform tepal identity across whorls.[22] In basal angiosperms like Magnolia, the outer tepal whorl lacks B-class gene expression (APETALA3 and PISTILLATA homologs), resembling sepals under A-class influence alone, while inner tepals may show partial overlap, yet overall similarity arises from broad AGL6-like expression promoting perianth traits.[23] In monocots such as lilies, an outward expansion of B-class genes to the first whorl creates petaloid outer tepals, blurring distinctions and supporting a "sliding boundary" variant of the model.[24] This genetic framework underscores how tepals evolve from conserved MADS-box gene networks, adapting perianth uniformity to diverse ecological roles.[25]Functions

Protection

The perianth acts as a primary mechanical barrier, shielding the immature reproductive organs of the flower from environmental stresses including desiccation, physical damage, and herbivory during the pre-anthesis stage.[3][13] The arrangement of perianth parts in the flower bud, known as aestivation, reinforces this protective role by forming a tight enclosure that limits pathogen entry and external threats. Imbricate and valvate aestivation patterns are particularly common in the calyx, the outer whorl, allowing overlapping or edge-to-edge contact that seals the bud effectively; valvate aestivation predominates in protective sepals to maintain integrity during development.[26][13] In certain species, the perianth persists post-anthesis, extending its protective function to developing fruits or seeds. For instance, in Helleborus foetidus, persistent sepals contribute photosynthetic resources to seed development, increasing seed mass.[27] Similarly, in apples (Malus domestica), the calyx with attached sepals remains at the fruit's stem end.[28] Thicker cuticles on sepaloid organs further minimize water loss, contributing to overall desiccation resistance.[3]Pollination Attraction

The perianth, especially the corolla, attracts pollinators through diverse coloration and patterns tailored to specific pollinator sensory capabilities. Petals often display pigments like anthocyanins for blue-violet hues that appeal to bees, or carotenoids contributing to red corollas that signal to birds while being inconspicuous to insect competitors.[29][30] These colors enhance long-distance visibility, with red predominating in bird-pollinated species to facilitate nectar access via tubular structures.[31] Ultraviolet (UV) patterns on petals serve as nectar guides, invisible to humans but detectable by insects like bees, directing them to reproductive structures. In sunflowers, UV bullseye patterns contrast with surrounding petal areas to highlight nectar rewards, while in Mimulus species, similar guides formed by pigment gradients improve pollinator efficiency.[32] These visual cues, often combined with white or yellow lines on petals, significantly boost pollination success; for example, in Lapeirousia oreogena, nectar guides increase male and female fitness by ensuring accurate proboscis insertion by fly pollinators, raising fruit set from 26% to 59%.[33] Olfactory attraction complements visuals, as glandular trichomes on tepals or petals emit volatile scents that lure pollinators from afar, with species-specific bouquets evolving to match insect or bird preferences.[32] Structural adaptations in the perianth further facilitate contact pollination, particularly in zygomorphic flowers where bilateral symmetry creates specialized landing platforms. In snapdragons (Antirrhinum majus), the ventral petal, regulated by genes like DIVARICATA, forms a broad platform that supports bee weight while guiding them toward anthers and stigma. Such modifications reduce handling time and increase pollen transfer precision. Evolutionarily, perianth persistence involves trade-offs; in mass-flowering species like petunias, post-pollination corolla wilting and abscission within 48 hours enable nutrient remobilization (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) to developing seeds, minimizing energy costs for maintenance after attraction duties are fulfilled. This ephemeral strategy optimizes resource allocation in high-density blooming, where rapid senescence supports fruit set without prolonged floral investment.Specialized Structures

Corona

The corona is a specialized appendage of the perianth in certain angiosperm flowers, typically manifesting as a cup-shaped, tube-like, or filamentary structure that arises from the bases of the corolla or filaments, often positioned between the petals and stamens.[34] In the Amaryllidaceae family, such as in Narcissus species (daffodils), it forms a prominent single corona, exemplified by the trumpet-like cup in Narcissus tazetta, which emerges as an independent structure late in floral development.[35] Conversely, in the Apocynaceae subfamily Asclepiadoideae (formerly Asclepiadaceae), coronas can be multiple, with up to five elements including staminal and interstaminal projections, as observed in species like Asclepias curassavica and Oxypetalum banksii.[36] In Passiflora (Passifloraceae), the corona consists of multiple rows of filaments, typically up to eight series, forming a colorful, elaborate fringe that encircles the reproductive organs.[37] Developmentally, the corona originates as an outgrowth of perianth or hypanthial tissue, initiating after the formation of the primary floral whorls (sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels), which underscores its status as a novel, fifth-like organ rather than a modification of existing ones.[35] In Narcissus bulbocodium, for instance, it begins as six discrete primordia from the hypanthium between tepals and stamens, later fusing into a coherent ring, with genetic markers like NbAGAMOUS indicating stamen-like identity but distinct from orthodox whorls.[34] In Asclepiadeae, coronas develop primarily from androecial tissue, though some species like Matelea denticulata exhibit both androecial and corolline types, often incorporating nectar-producing glands.[36] Cross-sections of these structures reveal vascular connections to the perianth base, with internal chambers or lobes that hold nectar, as seen in the lobed, villose interior of Narcissus coronas.[35] Functionally, the corona aids pollination by serving as a visual attractant through its vibrant colors and patterns, while physically guiding pollinators via its tube- or filament-like projections that direct access to nectar and reproductive parts.[38] In Narcissus, it enhances pollinator efficiency, particularly for short-styled flowers, by providing a nectar reservoir and structural barrier that promotes precise pollen transfer.[38] Similarly, in Asclepiadeae and Passiflora, the corona's nectar-holding capacity and filament arrays facilitate specialized pollination mechanisms, such as pollinia removal in milkweeds or filament-guided probing in passionflowers, thereby increasing reproductive success.[36][37]Other Modifications

In the Rosaceae family, the perianth undergoes modification through hypanthium formation, where the bases of sepals, petals, and often stamens fuse to create a cup-shaped structure that elevates and surrounds the gynoecium, contributing to floral and fruit development. This perigynous condition is evident in species like strawberries (Fragaria × ananassa), where the hypanthium enlarges post-fertilization to form the edible, fleshy pseudocarp that bears numerous small achenes on its surface.[39][40] Another notable modification occurs in the Asteraceae, where the calyx portion of the perianth evolves into a pappus—a persistent ring of capillary bristles, scales, or awns that aids in wind-mediated seed dispersal of the cypsela fruits. In sunflowers (Helianthus annuus), for instance, the pappus persists after corolla withering, enabling the lightweight fruits to be carried long distances by air currents. This adaptation enhances dispersal efficiency in open habitats.[41] Perianth reduction or complete absence represents an evolutionary simplification in many wind-pollinated angiosperms, resulting in apetalous flowers that prioritize pollen release over pollinator attraction. Oak species (Quercus spp.) exemplify this, with male catkins featuring stamens enclosed by a greatly reduced perianth consisting of 4-7 small lobes, minimizing energy allocation to non-essential structures.[42] In the Poaceae family, such as various grasses (e.g., wheat, Triticum aestivum), the perianth is drastically reduced to two or three minute, hygroscopic lodicules that briefly swell with moisture to pry apart the bract-like lemma and palea, exposing reproductive organs for anemophily without visual appeal.[43] Elaborations of the perianth also arise as specialized outgrowths, such as the nectar spurs formed from the inner whorl of petals in Aquilegia (columbine) species. These tubular extensions, varying in length from 1 to 5 cm across taxa, secrete nectar and match the tongue lengths of pollinators like bees or hawkmoths, driving diversification through pollinator specialization. In some Poaceae, bracts like the lemma can develop awns or subtle coloration that indirectly supports perianth-like protective or dispersive roles, though the family predominantly exhibits reduction.[44][45]Occurrence in Non-Flowering Plants

Bryophytes

In bryophytes, the perianth serves as a protective envelope around the female reproductive structures, particularly the archegonia, facilitating reproduction in moist environments. In mosses of the class Bryopsida, the archegonia are typically enclosed within a tubular perianth formed by modified leaves or gametophytic tissue, often resembling a calyptra and positioned on an archegoniophore in species like Funaria.[46] This structure shields the developing sporophyte from desiccation and mechanical damage during early embryogenesis.[47] In liverworts (Marchantiophyta), the perianth takes the form of a perigynium, a fleshy, tubular outgrowth of gametophytic tissue surrounding clusters of archegonia, as prominently seen in Marchantia polymorpha where it emerges from the ventral side of the thallus.[48] The perigynium provides a humid microenvironment essential for sperm motility and fertilization, often complemented by perichaetial bracts for additional protection.[49] Variations occur across taxa, with some leafy liverworts exhibiting plicate or smooth perianths that aid in species identification.[50] Evolutionarily, the bryophyte perianth represents a primitive adaptation for land colonization, analogous yet simpler than the perianth in angiosperms, primarily functioning to retain moisture around gametangia for water-dependent fertilization.[51] In Sphagnum species, pseudoperianths—thalloid tissues derived from gametophyte outgrowths—exhibit variations in thickness and inflation, enhancing buoyancy for dispersal in wetland habitats.[9] Fossil records from Triassic deposits, such as those of the bryophyte-like Naiadita lanceolata, reveal archegonia surrounded by perianth-like leaflike lobes approximately 300 μm long, indicating this structure's ancient role in reproductive protection.[52]Gymnosperms

In gymnosperms, which are seed-producing plants that lack flowers and fruits, the perianth is typically absent, as their reproductive structures are organized into cones (strobili) rather than floral organs.[53] The sporophylls in these cones bear naked seeds or pollen sacs without surrounding protective or attractive envelopes equivalent to a calyx or corolla. This absence reflects the evolutionary divergence of gymnosperms from angiosperms, where the perianth evolved as part of floral diversification for protection and pollination.[54] An exception occurs within the gnetophytes, a small but diverse subgroup of gymnosperms that includes Ephedra, Gnetum, and Welwitschia, where perianth-like structures have developed convergently.[55] These structures consist of bracts or fused bracteoles forming an envelope around the reproductive units, often termed a "perianth" due to their functional similarity to floral perianths in enclosing and potentially aiding in pollination.[55] For instance, in Ephedra (Ephedraceae), the microsporangiate (male) cones feature a perianth of connate bracteoles subtending microsporangiophores, while megasporangiate (female) cones have ovules enveloped by similar bract-like coverings that form a micropylar tube.[55] In Gnetum (Gnetaceae), the reproductive units exhibit integuments or bract-derived envelopes resembling a floral perianth, contributing to the flower-like appearance of their cones.[56] These modifications in gnetophytes highlight a partial convergence toward angiosperm floral traits, though they remain distinct in lacking true petals or sepals.[57]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/perigonium