Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

British Transport Police

View on Wikipedia

| British Transport Police Welsh: Heddlu Trafnidiaeth Prydeinig | |

|---|---|

Logo of the British Transport Police | |

| Abbreviation | BTP |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1 January 1949 |

| Preceding agencies |

|

| Annual budget | £328.1 million (2021/22)[1] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

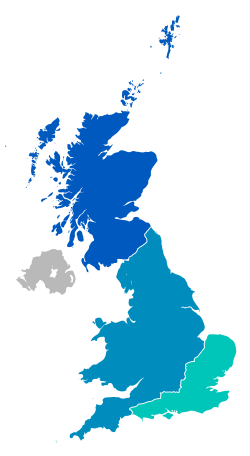

| National agency (Operations jurisdiction) | GB |

| Operations jurisdiction | GB |

| |

| Jurisdiction of the British Transport Police | |

| Legal jurisdiction | |

| Governing body | British Transport Police Authority |

| Constituting instruments |

|

| General nature | |

| Specialist jurisdiction |

|

| Operational structure | |

| Overseen by |

|

| Headquarters | Camden Road, London[3] 51°32′27″N 0°08′23″W / 51.5408°N 0.1398°W |

| Police Constables | 3,113[4] |

| PCSOs | 251[4] |

| Agency executive | |

| Divisions | |

| Website | |

| www | |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2025) |

The British Transport Police (BTP; Welsh: Heddlu Trafnidiaeth Prydeinig) is a national special police force[6] that polices the railway network of Great Britain (England and Wales, and Scotland), which consists of over 10,000 miles of track and 3,000 stations and depots.

BTP also polices the London Underground, Docklands Light Railway, West Midlands Metro, Tramlink, part of the Tyne and Wear Metro, Glasgow Subway and the London Cable Car.

The force is funded primarily by the rail industry.[7]

Jurisdiction

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

As well as having jurisdiction across the national rail network, the BTP is also responsible for policing:

- London Underground

- Docklands Light Railway

- London Trams

- London Cable Car

- Glasgow Subway

- Tyne and Wear Metro (Sunderland branch)[8]

- West Midlands Metro

This amounts to around 10,000 miles (16,000 km) of track and more than 3,000 railway stations and depots. There are more than one billion passenger journeys annually on the main lines alone.[9]

In addition, BTP, in conjunction with the French National Police (under the Border Police unit) – Police aux Frontières – police the international services operated by Eurostar.[10]

BTP is not responsible for policing the majority of the Tyne and Wear Metro, which is instead policed by Northumbria Police's Metro Unit,[8] nor the entirety of the Manchester Metrolink (policed by Greater Manchester Police). BTP also does not police heritage railways.

A BTP constable can act as a police constable outside their normal railway jurisdiction as described in the "Powers and status of officers" section.[11]

Previous jurisdiction

[edit]BTP constables previously had jurisdiction at docks, ports, harbours and inland waterways, as well at some bus stations and British Transport Hotels. These roles fell away in 1985 with privatisation. The legislation was amended to reflect this in 1994.[12]

History

[edit]Early days

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Private British railway companies employed detectives and police almost from the outset of passenger services in 1826. These companies were unified into four in 1923 then into a single nationalised company in 1947 by the Transport Act, which also created the British Transport Commission (BTC). On 1 January 1949 the British Transport Commission Police (BTCP) were created by the British Transport Commission Act 1949[13] which combined the already-existing police forces inherited from the pre-nationalisation railways by British Railways as well as the London Transport Police, canal police and several minor dock forces. In 1957 the Maxwell-Johnson enquiry found that policing requirements for the railway could not be met by territorial forces and that it was essential that a specialist police force be retained. On 1 January 1962 the British Transport Commission Police ceased to cover British Waterways property[14] and exactly a year later when the BTC was abolished the name of the force was amended to the British Transport Police.

Racism

[edit]In the 1960s and 1970s BTP officers led by Detective Sergeant Derek Ridgewell gave false testimony to obtain convictions of young men in the British Black community on the London Underground on charges such as assault with intent to rob. Eventually some of the men, who became known as the Oval Four and Stockwell Six, managed to have their convictions overturned. In November 2021, the BTP chief constable apologised to the black community for the trauma caused by Ridgewell, and said his actions did "not define the BTP of today".[15] In July 2021 Deputy Chief Constable Adrian Hanstock stated that a review of Ridgewell's record had "not identified any additional matters that we feel should be referred for external review",[16] this proved not to be a reliable statement as the Criminal Case Review Commission subsequently quashed the convictions of Basil Peterkin and Saliah Mehmet, 2 of 12 men convicted on Ridgewell's evidence of theft from a goods depot in 1977. The CCRC appealed for "anyone else who believes that they or a loved one, friend or acquaintance was a victim of a miscarriage of justice to contact the CCRC – particularly if DS Derek Ridgewell was involved.",[17] In January 2025, following after the Ronald De Souza's case was quashed, the victim's solicitor stated "I am not confident that all his victims have yet been identified." and the CCRC issued a direct appeal for anyone convicted in a case involving Ridgwell to come forward if they believed they were a victim of a miscarriage of justice.[18] That sentiment was echoed in July 2025 when the solicitor for 13th victim Errol Campbell's family stated that there were that "bound to be others".[19]

Changes

[edit]In 1984 London Buses decided not to use the British Transport Police. The British Transport Docks Board followed in 1985 when it was privatised. This included undertaking immigration control at smaller ports until the Immigration Service expanded. The force crest still includes ports and harbours.[citation needed] BTP left the last ports it policed in 1990. The force played a central role in the response to the 7 July 2005 London bombings. Three of the incidents were at London Underground stations: Edgware Road (Circle Line), Russell Square and Aldgate stations, and the Number 30 bus destroyed at Tavistock Square was very close to the then force headquarters of the BTP, the latter incident being responded to initially by officers from the force.[citation needed]

Historically, railway policing powers were derived from a mixture of common-law constable powers, various statutory provisions, and industry agreements. In the nineteenth century, this included the use of special constables appointed by magistrates under the Special Constables Act 1838, which enabled justices of the peace to swear in and remunerate constables for the protection of public works, including railways, at the request and expense of the companies concerned.[Note 1] The modern position was consolidated onto a unified statutory footing—first through the Transport Police (Jurisdiction) Act 1994[12] (amending British Transport Commission Act 1949 s 53) and then, comprehensively, through s 31 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003.[20][12]

21st century

[edit]In 2010, the force's dog training was moved from a force-specific training establishment near Tadworth, Surrey (opened in 1984) to the Metropolitan Police's Dogs Training School in Keston, London Borough of Bromley. In May 2011, the Secretary of State for Transport Philip Hammond announced that British Transport Police would create an armed capability of its own with the added benefit of additional resilience and capacity to the overall UK police armed capability.[21] The BTP are deployed on armed patrols using Glock 17 pistols, LMT AR-15 CQB carbines[22] and tasers.[23]

List of chief constables

[edit]The BTP was led by a chief police officer from its inception until 1958, when Arthur West was appointed its first chief constable.[24]

- Arthur West (1958–1963)

- William Owen Gay (1963–1974)

- Eric Haslam (1974–1981)

- Kenneth Ogram (1981–1989)

- Desmond O'Brien (1989–1997)

- David Williams (1997–2001)

- Ian Johnston (2001–2009)

- Andrew Trotter (2009–2014)

- Paul Crowther (2014–2021)

- Lucy D'Orsi (2021–present)

Crime types

[edit]Route crime

[edit]Route crime collectively describes crimes and offences of trespass and vandalism which occur on railway lines and can affect the running of train services.[25] The majority of deaths are due to suicide or trespass.[26]

Graffiti costs rail firms over £5 million a year in direct costs alone.[27] The BTP maintains a graffiti database which holds over 1900 graffiti tags, each unique to an individual. In 2005 BTP sent 569 suspects to court (an increase of 16% on 2004 figures).[28]

In the North West Area BTP has joined forces with Lancashire Constabulary and Network Rail to combat theft of metal items and equipment from railway lines in an initiative called Operation Tremor. The BTP established Operation Drum in 2006 as a national response to the increase in metal theft offences and also chairs the relevant Association of Chief Police Officers working group.[29]

Passenger crime

[edit]Operation Shield is an initiative by BTP to reduce the number of knives carried by passengers on the rail network. This initiative came about after knife crime began to rise and also because of the murder of a passenger on a Virgin CrossCountry service travelling from Glasgow.[30]

In 2013, in response a survey conducted by Transport for London, which showed that 15% of women using public transport in London had been the subject of some form of unwanted sexual behaviour but that 90% of incidents went unreported, the BTP—in conjunction with the Metropolitan Police Service, City of London Police, and TfL—launched Project Guardian, which aimed to reduce sexual offences and increase reporting.[31]

In November 2016, BTP introduced the "See It, Say It, Sorted" slogan in posters and on-train tannoy announcements, encouraging passengers to report suspicious activity.[32][33] The slogan has gained wide recognition.[34]

Hate Crimes

[edit]During the mid-2020s, BTP reported elevated levels of hate crime in London across public transport. Asked about hate crime on buses, Chief Superintendent Chris Casey of the BTP told a City Hall meeting that international conflicts were “playing out” on London’s transport network. Police linked an increase in antisemitic incidents to the Israel–Gaza conflict that began in late 2023, as well as to the associated wave of pro-Palestinian protests in London. As part of its ongoing work, BTP has collaborated with the Metropolitan Police Service, Transport for London and other partners in a multi-agency effort to manage public protests, encourage the reporting of hate crime, and support wider city-wide prevention strategies.[35][36][37]

Funding

[edit]The British Transport Police is almost wholly funded by the train operating companies, Network Rail, and the London Underground – part of Transport for London.[38] Around 95% of BTP's funding comes from the train operating companies.[39] Other operators with whom the BTP has a service agreement also contribute appropriately. This funding arrangement does not give the companies power to set objectives for the BTP, but there are industry representatives serving as members of the police authority.[40] The police authority decides objectives. The industry membership represent five out of 13 members.[citation needed]

The force does not receive any direct funding from the Home Office, but may apply for grants – such as for special events, like the London 2012 Olympic Games.[7] With BTP now playing a large role in counter-terrorism on the rail network, the force also receives some grants towards its firearms units.[citation needed]

The police authority has agreed its budget for 2021–22 at £328.1 million.[41]

Operational structure

[edit]As of September 2025[update], BTP had a workforce of 2,852 police officers, 1,619 police staff & designated officers, 189 police community support officers, 211 special constables, and 42 support volunteers.[4]

Divisions

[edit]From 1 April 2014, the divisional structure changed from the previous seven division structure to a four division structure - according to BTP this new structure will 'deliver a more efficient force, generating savings to reinvest in more police officers across the railway network'.[42]

A Division

[edit]Based at BTP headquarters in Central London, this division retains overall control of the other divisions and houses central functions including forensics, CCTV and major investigations. As of 2015[update], 393 police officers, ten special constables and 946 police staff were based at FHQ.[43]

B Division

[edit]This division covers London and the South East and southern areas of England. This division is further divided into the following sub-divisions:

As of 2015[update], B Division housed 1,444 police officers, 101 special constables, 191 PCSOs and 361 police staff.[43]

C Division

[edit]

This division covers the North East, North West, the Midlands, South West areas of England and Wales. This division is further divided into the following sub-divisions:

As of 2015[update], C Division housed 921 police officers, 127 special constables, 132 PCSOs and 180 police staff.[43]

D Division

[edit]This division covers Scotland. There are no sub-divisions within D Division.[50]

As of 2015[update], D Division housed 214 police officers, 24 special constables and 46 police staff.[43]

E Division

[edit]E Division (Specialist Operations) was formed in 2020, removing the counter-terrorism units and assets from A Division, and placing them into their own division.

E division comprises the force's specialist counter-terrorism units including the Firearms Unit, Dog Branch, Specialist Response Unit and others.

Former divisions

[edit]Prior to April 2014, BTP was divided into seven geographical basic command units (BCUs) which it referred to as 'police areas':

- Scotland (Area HQ in Glasgow)

- North Eastern (Area HQ in Leeds)

- North Western (Area HQ in Manchester)

- London North (Area HQ in London - Caledonian Road)

- London Underground (Area HQ in London - Broadway)

- London South (Area HQ in London - London Bridge Street)

- Wales & Western (Area HQ in Birmingham)

Prior to 2007, there was an additional Midland Area and Wales and West Area; however, this was absorbed into the Wales and Western area and North Eastern area.[citation needed]

Communications and controls

[edit]BTP operates two force control rooms and one call-handling centre:

- First Contact Centre: Based in Birmingham and responsible for handling all routine telephone traffic. This facility was created further to criticism by HMIC.[51][52]

- Force Control Room – Birmingham: Based in Birmingham – alongside the First Contact Centre – and responsible for C and D Divisions which cover the East Midlands, West Midlands, Wales, the North West of England, the North East of England, the South West of England and Scotland.

- Force Control Room – London: Responsible for B Division which covers the South and East of England including Greater London (both TfL and Mainline).

Both FCRL and FCRB house an events control suite, and a 'silver suite' incident control room is located in the South East for coordinating major incidents and as a fallback facility.

The Home Office DTELS callsign for BTP is 'M2BX' and their events control suite is 'M2AZ' for force-wide events and incidents, and the South East and 'M2AY' for Outer London events and incidents.

BTP also have consoles within the Metropolitan Police C3i Special Operations Room (SOR).

The BTP can be contacted via their 61016 text service.[53] In November, 2024, BTP made agreements with the four mobile network operators in the UK to make the service free.[54]

Custody suites

[edit]The force only acquired the power to designate custody suites in 2001,[55] whereby all of the custody suites up until that point were non-designated. The force previously ran a number of non-designated custody suites around the country, which had all been closed down by 2014.[56] A non-designated custody suite only allows police to detain someone for six hours before they are either released (whether charged, bailed or released without charge) or transferred to a designated facility.

The force retains one designated custody suite that is operational at Brewery Road in London (20 cells), where persons arrested within a reasonable travelling distance are taken, plus a temporary custody suite at Wembley Park that is used for some events.[57]

A number of other BTP custody suites were operational in London but these were closed in 2017 due to concerns regarding the time that it took to transport prisoners there.[58]

Specialist units

[edit]

Emergency Response Unit

[edit]

From 2012, as a result of a recommendation following the 7 July 2005 London bombings, BTP embedded officers with TfL's Emergency Response Unit (ERU). ERU vehicles were given blue lights and police markings, and driven by a BTP officer, to enable the unit to reach emergencies quicker. The unit carries TfL engineers to incidents on the London Underground, such as one under accidents and terrorist incidents. The vehicles are driven by BTP officers, so once at the scene the officer performs regular policing duties in relation to any crime or public safety issues. The use of the blue lights on the unit's vehicles is subject to the same criteria as with any other police vehicle.[59][60][61] In December 2013, TfL announced that the trial of blue lights had ended, and that ERU vehicles would retain blue lights, as BTP drivers had halved the unit's response time to incidents.[62] The use of police livery and blue lights ended in 2024 after a review determined that it did not meet national guidelines for blue-light responses.[63]

Emergency Intervention Unit

[edit]Similar schemes have been implemented elsewhere in the country, including a partnership with Network Rail and South West Trains (SWT) in which a BTP officer crews an "Emergency Intervention Unit", which conveys engineers and equipment to incidents on SWT's network using blue lights.[64] The scheme won the "passenger safety" category at the UK Rail Industry Awards in 2015.[65][66] Another "Emergency Response Unit" was established in partnership with Network Rail in the Glasgow area in the run-up to the 2014 Commonwealth Games.[67]

Medic Response Unit

[edit]In May 2012, the BTP formed the Medic Response Unit to respond to medical incidents on the London Underground network, primarily to reduce disruption to the network during the 2012 Summer Olympics. The scheme was initially for a 12-month trial, and consisted of 20 police officers (18 police constables and two sergeants) and two dedicated fast-response cars. The officers attached to the unit each undertook a four-week course in pre-hospital care, funded by TfL. TfL estimated that around one third of delays on the London Underground were caused by "passenger incidents", of which the majority related to medical problems with passengers; the purpose of the unit is to provide a faster response to medical incidents, providing treatment at the scene with the aim of reducing disruption to the network.[68] The unit also aims to assist passengers who may be distressed after being trapped on trains while an incident at a station is resolved. Its training and equipment is the same as that of the London Ambulance Service in order to ensure smooth hand-overs of patients.[69] At the end of the trial period, in October 2013, the unit was reduced to eight officers; the other twelve returned to regular policing duties after TfL judged the results of the scheme to be less than conclusive.[62] Officers from the unit treated over 650 people in the first year of operation, including rescuing a passenger who fell onto the tracks, and made 50 arrests.[70]

Firearms unit

[edit]In May 2011, the Secretary of State for Transport announced with agreement from the Home Secretary that approval had been given for BTP to develop a firearms capability following a submission to government in December by BTP.[71][72][73] Government stated that this was not in response to any specific threat, and pointed out that it equipped the BTP with a capability that was already available to other police forces and that BTP relied upon police forces for assistance which was a burden.[73]

In February 2012, BTP firearms officers commenced patrols focusing on mainline stations in London and transport hubs to provide a visible deterrence and immediate armed response if necessary.[74] Firearms officers carry a Glock 17 handgun and a LMT CQB 10.5" SBR carbine that may be fitted with a suppressor and are trained to armed response vehicle standard.[75][Note 2]

In 2014, the Firearms Act 1968 was amended to recognise BTP as a police force under the Act in order to provide BTP a firearms licensing exemption the same as other police forces.[78]

In December 2016, firearms officers commenced patrolling on board train services on the London Underground.[79]

In May 2017, as part of the response to the Manchester Arena bombing, it was announced that firearms officers would patrol on board trains outside London for the first time.[79]

In June 2017, BTP announced that the force firearms capability would be expanding outside of London with plans to establish armouries and hubs at Birmingham and Manchester. In October 2017, BTP commenced an internal advertisement requesting expressions of interest from substantive constables for the role of firearms officers at Birmingham and Manchester.[citation needed]

Powers and status of officers

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

General powers

[edit]Under s.31 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003, British Transport Police officers have "all the power and privileges of a constable" when:

- on track (any land or other property comprising the permanent way of any railway, taken together with the ballast, sleepers and rails laid thereon, whether or not the land or other property is also used for other purposes, any level crossings, bridges, viaducts, tunnels, culverts, retaining walls, or other structures used or to be used for the support of, or otherwise in connection with, track; and any walls, fences or other structures bounding the railway or bounding any adjacent or adjoining property)[80]

- on network (a railway line, or installations associated with a railway line)[80]

- in a station (any land or other property which consists of premises used as, or for the purposes of, or otherwise in connection with, a railway passenger station or railway passenger terminal (including any approaches, forecourt, cycle store or car park), whether or not the land or other property is, or the premises are, also used for other purposes)[80]

- in a light maintenance depot,

- on other land used for purposes of or in relation to a railway, the transport police

- on other land in which a person who provides railway services has a freehold or leasehold interest, and

- throughout Great Britain for a purpose connected to a railway or to anything occurring on or in relation to a railway.

"Railway" means a system of transport employing parallel rails which provide support and guidance for vehicles carried on flanged wheels, and form a track which either is of a gauge of at least 350 millimetres or crosses a carriageway (whether or not on the same level).[81]

A BTP constable may enter

- the track,

- a network,

- a station,

- a substation,

- a light maintenance depot, and

- a railway vehicle.

without a warrant, using reasonable force if necessary, and whether or not an offence has been committed.[82]

London Cable Car

[edit]BTP officers derive their powers to police the London Cable Car from the London Cable Car Order 2012.[83]

Outside natural jurisdiction

[edit]BTP officers need, however, to move between railway sites and often have a presence in city centres. Consequently, they can be called upon to intervene in incidents outside their natural jurisdiction. ACPO (now the NPCC) estimate that some 8,000 such incidents occur every year. As a result of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001[84] BTP officers can act as police constables outside their normal jurisdiction in the following circumstances:

On the request of a constable

[edit]If requested by a constable of:

- a territorial police force,

- the Ministry of Defence Police (MDP), or

- the Civil Nuclear Constabulary (CNC)

to help assist an officer in the execution of their duties in relation to a particular incident, investigation or operation, a BTP constable also has the powers of the requesting officer for the purposes of that incident, investigation or operation.[85] If a constable from a territorial police force makes the request, then the powers of the BTP constable extend only to the requesting constable's police area.[85] If a constable from the MDP or CNC makes the request, then the powers of the BTP officer are the same as those of the requesting constable.[85]

On the request of a chief constable (mutual aid)

[edit]

If requested by the chief constable of one of the forces mentioned above, a BTP constable takes on all the powers and privileges of members of the requesting force.[86] This power is used for planned operations, such as the 2005 G8 summit at Gleneagles.

Spontaneous requirement outside natural jurisdiction

[edit]A BTP constable has the same powers and privileges of a constable of a territorial police force:[85]

- in relation to people whom they suspect on reasonable grounds of having committed, being in the course of committing or being about to commit an offence, or

- if they believe on reasonable grounds that they need those powers and privileges in order to save life or to prevent or minimise personal injury or damage to property.

A BTP constable may only use such powers if they reasonably believe that waiting for a local constable (as above) would frustrate or seriously prejudice the purpose of exercising them.[85]

The policing protocol between BTP and Home Office forces set outs the practical use of these extended powers.

"Other than in the circumstances set out under Mutual Aid, British Transport Police officers will not normally seek to exercise extended jurisdiction arrangements to deal with other matters unless they come across an incident requiring police action whilst in the course of their normal duties. Whenever British Transport Police officers exercise police powers under the Extended Jurisdiction Arrangements the BTP Chief Constable will ensure that the relevant Local Chief Constable is notified as soon as practicable."

— ACPO Policing Protocol between BTP & Home Office Forces,[87] October 2008

Channel Tunnel Act 1987

[edit]When policing the Channel Tunnel, BTP constables have the same powers and privileges as members of Kent Police when in France,[88] and will also be under the direction and control of the Chief Constable of Kent.[88]

Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994

[edit]A BTP constable can:

- When in Scotland, execute an arrest warrant, warrant of commitment and a warrant to arrest a witness (from England, Wales or Northern Ireland),[89] and

- When in England or Wales, execute a warrant for committal, a warrant to imprison (or to apprehend and imprison) and a warrant to arrest a witness (from Scotland).[89]

When executing a warrant issued in Scotland, a BTP constable executing it shall have the same powers and duties, and the person arrested the same rights, as they would have had if execution had been in Scotland by a constable of Police Scotland.[89] When executing a warrant issued in England, Wales or Northern Ireland, a constable may use reasonable force and has specified search powers provided by section 139 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994.[89]

Policing and Crime Act 2017

[edit]A BTP constable, other than a special constable, can:

- When in Scotland, arrest an individual they suspect of committing a specified offence in England and Wales or Northern Ireland if the Constable is satisfied that it would not be in the best interests of justice to wait until a warrant has been issued under the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 2004.[90]

- When in England or Wales, arrest a person they suspect of committing a specified offence in Scotland or Northern Ireland, or the constable has reasonable grounds to believe that the arrest is necessary to allow the prompt and effective investigation of the offence or prevent the prosecution of the offence being hindered by the disappearance of the individual.[90]

The power can be exercised on or off of transport property without restriction.

This is the only known power that is available to 'regular' BTP constables and not BTP special constables as a result of the Policing and Crime Act 2017 stating that the power is available to constables attested under Section 24 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 (BTP special constables are appointed under Section 25 of the aforementioned Act).

National and international maritime policing powers

[edit]BTP constables (both 'regular' and special constables) are designated as law enforcement officers in the same way as members of a territorial police force under Chapter 5 of the Act. This allows them to exercise maritime enforcement powers, including the powers of arrest for offences that could be subject to prosecution under the laws of England and Wales, Northern Ireland or Scotland, in relation to:

- a British ship in England and Wales, Northern Ireland or Scottish waters, foreign waters or international waters,

- a ship without nationality in England and Wales waters or international waters,

- a foreign ship in England and Wales waters or international waters, or

- a ship, registered under the law of a relevant territory, in England and Wales waters or international waters.[91]

Attestation

[edit]Constables of the BTP are required by S.24 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 (and special constables of the BTP are required by S.25) to make one of the following attestations, depending on the jurisdiction in which they have been appointed:

England and Wales

[edit]I, [name], of British Transport Police, do solemnly and sincerely declare and affirm, that I will well and truly serve the King, in the office of constable, with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality, upholding fundamental human rights and according equal respect to all people; and that I will, to the best of my power, cause the peace to be kept and preserved, and prevent all offences against people and property; and that while I continue to hold the said office, I will, to the best of my skill and knowledge, discharge all duties thereof faithfully according to law.

[Police Act 1996, Schedule 4 as amended.]

The attestation can be made in Welsh.

Scotland

[edit]Constables are required to make the declaration required by s.10 of the Police and Fire Reform (Scotland) Act 2012 before a sheriff or justice of the peace.

I do solemnly, sincerely and truly declare and affirm that I will faithfully discharge the duties of the office of constable with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality, and that I will uphold fundamental human rights and accord equal respect to all people, according to law.

Status

[edit]A BTP constable does not lose the ability to exercise his powers when off duty. Section 22 of the Infrastructure Act 2015[92] repealed section 100(3)(a) of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001[93] which required BTP officers to be in uniform or in possession of documentary evidence (i.e. their warrant card) in order to exercise their powers. The repeal of this subsection, which came into effect on 12 April 2015,[94] now means BTP officers are able to use their powers on or off duty and in uniform or plain clothes regardless of whether they are in possession of their warrant card.[95]

On 1 July 2004 a police authority for the British Transport Police was created.[96] BTP officers became employees of the police authority; prior to that, they were employees of the Strategic Rail Authority.

Rank insignia

[edit]| British Transport Police ranks and insignia[97] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Chief constable (CC) |

Deputy chief constable (DCC) |

Assistant chief constable (ACC) |

Chief superintendent | Superintendent | Chief inspector | Inspector | Sergeant | Constable | PCSO |

| Epaulette insignia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Special constabulary

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

British Transport Police first recruited special constables in a trial based in the North West Area in 1995, and this was expanded to the whole of the UK. Many specials are recruited from the wider railway community and those working for train operating companies are encouraged by their employers.

Under the terms of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 and the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, BTP special constables have identical jurisdiction and powers to BTP regular constables; primary jurisdiction on any railway in Great Britain and a conditional jurisdiction in any other police force area.

BTP specials do not wear the 'SC' insignia (a crown with the letters SC underneath) on their epaulettes unlike some of their counterparts in some Home Office police forces.[98]

As of March 2023, the BTP Special Constabulary held a headcount of just over 240 officers working across Great Britain.[99] The headcount for the Special Constabulary sits just under 500.

In January 2022 the British Transport Police Police Federation allowed BTP special constables to join,[100][101] a precondition for an announcement in May 2022 that specials would be trained to carry tasers.[102]

As of January 2024, the need to complete a promotion exam was removed, and two ranks were removed; special superintendent and special chief inspector. It continues to be led by a special chief officer and a special deputy chief officer. Each division has a number of special inspectors and special sergeants who continue to lead and manage their teams. The BTP Special Constabulary rank structure differs from the regular officers' structure, although some are similar.[103]

The structure is as follows:

| Rank | Special chief officer | Special deputy chief officer | Special chief inspector

(Not currently used) |

Special inspector | Special sergeant | Special constable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epaulette insignia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Special constables can progress up the rank structure. Whilst the names may be similar to other ranks (e.g. inspector), the insignia is different, so that regulars and specials can be easily distinguished.

Special constables in the BTP volunteer at least sixteen hours per month, similar to Home Office forces. They also aim to reach Independent Patrol Status (IPS) and then, if so desired, can volunteer in different departments, including:[104]

- Operational Support Unit (OSU)

- Criminal Investigation Department (CID) (including Major Serious and Organised Crime, MSOC)

- Civil Protection Unit

- Disruption Tasking Team

- Violent Crime Task Force.

For specials joining for England and Wales stations, training is completed in London, and for Scottish specials it is in Glasgow. Phase One training is 26 days, in person, with additional online training sessions. Accommodation is provided. A reduced training course is available for transferee specials (volunteers who transfer in from other police forces).[105]

Police community support officers (PCSO)

[edit]

British Transport Police is the only special police force that employs police community support officers (PCSOs). Under Section 28 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003, can allow the BTP Chief Constable to recruit PCSOs and designate powers to them using the Police Reform Act 2002, which previously only extended to chief constables or commissioners of territorial police forces. [106][107]

The BTP started recruiting PCSOs on 13 December 2004.[108] They were on patrol for the first time on Wednesday 5 January 2005,[109] who mostly work in the force's neighbourhood policing teams (NPTs).

BTP is one of only three forces to issue its PCSOs handcuffs, the others North Wales Police and Dyfed-Powys Police. This also includes leg restraints.[110] BTP PCSOs also utilise generally more powers than their counterparts in other forces.[111][112]

Although BTP polices in Scotland (D Division) it does not have any PCSOs in Scotland due to limitations of the Police Reform Act 2002, the law that empowers PCSOs which does not extend to Scotland. Although unlike police officers there is no formal transfer process.[113] BTP is known to often attract PCSOs already serving in other police forces.[114][115]

One of BTPs PCSOs is credited with making the force's largest ever illegal drugs seizure from one passenger when on 30 September 2009 PCSO Dan Sykes noticed passenger James Docherty acting suspiciously in Slough railway station only to find him in possession of £200,000 worth of Class C drugs. PCSO Sykes then detained Docherty who was then arrested and later imprisoned after trial.[116]

In 2006 PCSO George Roach became the first BTP PCSO to be awarded a Chief Constable's Commendation after he saved a suicidal man from an oncoming train at Liverpool Lime Street railway station.[117]

Accident investigation

[edit]Until the 1990s the principal investigators of railway accidents were the inspecting officers of HM Railway Inspectorate, and BTP involvement was minimal. With major accidents after the 1988 Clapham Junction rail crash being investigated by more adversarial public inquiries, the BTP took on a more proactive role in crash investigations. Further reforms led to the creation by the Department for Transport of the Rail Accident Investigation Branch which takes the lead role in investigations of accidents.[citation needed]

British Transport Police Authority

[edit]The British Transport Police Authority is the police authority that oversees the BTP. A police authority is a governmental body in the United Kingdom that defines strategic plans for a police force and provides accountability[118] so that the police function "efficiently and effectively",[119] and the BTP patrol the railways in England, Wales, and Scotland.[120]

The chair, appointed by the Secretary of State for Transport, was Alistair Graham from its founding in 2004 until the end of 2011, Millie Banerjee[121] from 2011 to 2015. Esther McVey served as chair from 2015 to 2017. Ron Barclay-Smith was appointed as chair in 2018.[122]

Proposed mergers and jurisdiction reforms

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Although the British Transport Police is not under the control of the Home Office, and as such was not included as part of the proposed mergers of the Home Office forces of England and Wales in early 2006, both the then London mayor Ken Livingstone and then head of the Metropolitan Police Sir Ian Blair stated publicly that they wanted a single police force in Greater London. As part of this, they wished to have the functions of the BTP within Greater London absorbed by the Metropolitan Police. However, following a review of the BTP by the Department for Transport, no changes to the form and function of the force were implemented, and any proposed merger did not happen.[123]

There were Scottish government proposals for the BTP's Scottish division (D Division) to be merged with Police Scotland. However, the merger was postponed indefinitely in August 2018.[124][125]

In 2006 it was suggested BTP take on airport policing nationally.

In 2010, it was suggested that BTP take on VOSA traffic officers and Highways England traffic officers. It was estimated BTP would save £25 million if this went ahead.[126] Contrary to popular belief, it was not proposed to merge Home office forces traffic units.

As of 2017 the government made a manifesto commitment to merge BTP, the Civil Nuclear Constabulary and Ministry of Defence Police into a single "British Infrastructure Police". Originally after the 2015 Paris attacks, it was thought fully arming BTP and merging the three force would create a significant boost to firearms officer numbers in the UK and they could act as a nationwide counter terrorism force. Two options for this were developed;

Option 1: A single National Infrastructure Constabulary combining the function of the Civil Nuclear Constabulary, the Ministry of Defence Police, the British Transport Police, the Highways England Traffic Officer Service, DVSA uniformed enforcement officers and Home Office police forces' airport and port police units, along with private port police; or

Option 2: A Transport Infrastructure Constabulary and an Armed Infrastructure Constabulary, with the first bringing together the functions carried out by BTP, the Highways England Traffic Officer Service, DVSA uniformed enforcement officers and Home Office police forces' airport and port police units, along with private port police. The Armed Infrastructure force would be a merger of MDP and CNC.

Discussing the review in January 2017, DCC Hanstock commented on the specific responsibilities of BTP and stakeholder responses to the infrastructure policing review:

"What is different is the environment—understanding the risks, threats and health and safety elements—and being specially trained to operate in a transport way. Added to that is understanding the implications of how we do our business: the commercial imperative and the impact of what you do in one area of the network on what happens elsewhere, which may be hundreds of miles up country, based on decisions you make here. There is some true uniqueness about the British Transport police, which I think is treasured by the industry and stakeholders, and that is reflected in quite a bit of the feedback we have received about nervousness about some of these proposals."

In June 2018 it was reported that these proposals had also been shelved for the time being. The only consensus it seems is that BTP would be suited to taking on airport and port policing as opposed to other modes of transport.

See also

[edit]Note(s)

[edit]- ^ The Special Constables Act 1838 did not establish a permanent or general police force. It enabled magistrates (justices of the peace) to appoint temporary special constables with full constabulary powers to preserve the peace in connection with specified public works (including railways), typically at the request and expense of the undertakings concerned. These appointments were localised, time-limited, and supervisory in nature, and did not confer an independent policing jurisdiction on companies themselves.

- ^ The Firearms Unit whilst training firearms officers to Armed Response Vehicle (ARV) standard does not conduct ARV patrols; however, it uses vehicles to transport officers and tactical equipment to and from stations.[76][77]

References

[edit]- ^ BTPA Strategic Plan 2018-22 (Report). British Transport Police Authority. 2022. p. 24. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN THE BRITISH TRANSPORT POLICE AUTHORITY AND THE SCOTTISH POLICE AUTHORITY FOR THE OPERATION OF THE SCOTTISH RAILWAYS POLICING COMMITTEE" (PDF).

- ^ "Department contact details". British Transport Police. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Police Workforce, England and Wales: 30 September 2021 (Report). Home Office. 26 January 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Chief Officers". British Transport Police. Retrieved 3 November 2025.

- ^ "s.3(5) Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ a b "British Transport Police's response to the funding challenge" (PDF). 21 June 2019.

- ^ a b "Kim McGuinness announces Metro to get security teams on the majority of evening train services". Northumbria Police & Crime Commissioner. 19 May 2023. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Transport Statistics Great Britain: 2021". gov.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "BTP site "About Us"". Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ "Do British Transport Police officers have the same powers as other police officers? | West Yorkshire Police". www.westyorkshire.police.uk. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ a b c "British Transport Police (HC 488, 2003–04)" (PDF). House of Commons. HC 488. House of Commons of the United Kingdom. 4 June 2004. Retrieved 11 January 2026.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Transport Police (Jurisdiction) Act 1994". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Sharpness Dock Police (1874–1948)". Archived from the original on 14 June 2004. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

- ^ Gayle, Damien; Mohdin, Aamna (5 November 2021). "British Transport Police apologise to UK black community for corrupt ex-officer". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (25 January 2024). "'I just went bent': how Britain's most corrupt cop ruined countless lives". The Guardian.

- ^ "Convictions quashed after persistent pro-active CCRC investigation". 18 January 2024.

- ^ "Final Stockwell Six case referred over corrupt cop Paul Green (left) and Cleveland Davidson hold their linked hands aloft outside the entrance to the Royal Courts of Justice". BBC News. 31 January 2025. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ Warren, Jess (17 July 2025). "Two framed by corrupt officer decades ago cleared A black and white photo of Derek Ridgewell Image caption, Det Sgt Derek Ridgewell was responsible for a series of racist miscarriages of justice". BBC News. Retrieved 23 September 2025.

- ^ "Explanatory Notes to Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 – Background – paragraph 59". Opsi.gov.uk. 11 August 2003. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Transport police to be armed to counter terror threat". BBC News. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- ^ "Lewis Machine & Tool Company - Complete Weapon Systems". Lmtdefense.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Policing the railways - Armed police". British Transport Police. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2012 – via YouTube.

- ^ Gordon, Kevin. "A Time Line of Policing the Railways" (PDF).

- ^ "Route crime". Office of Rail Regulation. 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Annual Safety Performance Report 2005" (PDF). Rail Safety Standards Board (RSSB). 16 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

- ^ "BTP: Issues, graffiti". British Transport Police. Archived from the original on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ^ The Sharp End Issue 16 (published for the Home Office and sent to every police officer, SC and support staff in England and Wales)

- ^ http://www.btp.presscentre.com/content/Detail.asp?ReleaseID=1404&NewsAreaID=2/ [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Man quizzed over stabbing". BBC News. 28 May 2006. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ Bates, Laura (1 October 2013). "Project Guardian: making public transport safer for women". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Sleigh, Sophia (27 June 2022). "'See It. Say It. Sorted.' Is Staying Despite Promise To Banish Tannoy Spam". HuffPost UK. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ Simpson, Francesca Gillett, Fiona (8 November 2016). "Posters for new police anti-terror campaign likened to Nazi propaganda". Evening Standard. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Silvester, Andy (19 March 2025). "How 'See it. Say it. Sorted.' became Britain's most effective earworm". www.thetimes.com. Retrieved 13 October 2025.

- ^ Jaffer, Kumail (17 December 2025). "Israel-Gaza conflict fuels hate crime on London's public transport". The Standard. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- ^ "Israel-Gaza conflict continues to fuel high levels of hate crime on tubes and buses". Southwark News. 18 December 2025. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- ^ "UK police plan tougher action against antisemitic chants and protests". reuters.com. Retrieved 29 December 2025.

- ^ British Transport Police Annual Report 2004/2005 (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- ^ Ayling, Julie; Shearing, C. (2008). "Taking Care of Business: Public police as commercial security vendors". Criminology and Criminal Justice. 8 (1): 27–50. doi:10.1177/1748895807085868. hdl:10072/62559. S2CID 144390902.

- ^ "Police Authority". Archived from the original on 29 April 2009.

- ^ BTPA Strategic Plan 2018-22 (Report). British Transport Police Authority. 2022. p. 24. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Our structure". British Transport Police. 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Statistical Bulletin 2014/15" (PDF). British Transport Police. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "B Division East Policing Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ British Transport Police (2014)"B Division TfL Policing Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ British Transport Police (2014) "B Division South Policing Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ British Transport Police (2014) "C Division Pennine Policing Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ British Transport Police (2014) "C Division Midland Policing Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "C Division Wales" (PDF). British Transport Police. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "D Division Policing Plan" (PDF). British Transport Police. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ "HMIC – Baseline Assessment Project" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ "BTP – Control Room Project". Archived from the original on 1 February 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ British Transport Police, 61016 text service, accessed on 2 December 2024

- ^ Devonshire, James (26 November 2024). "British Transport Police's 61016 text service now free across all major UK mobile networks". Emergency Services Times. Retrieved 20 September 2025.

- ^ "Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 Schedule 7". Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Report on an announced inspection visit to police custody suites of the British Transport Police" (PDF). 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Report on an inspection visit to the British Transport Police custody suite". HMICFRS. 10 October 2025. Retrieved 1 November 2025.

- ^ "British Transport Police to downsize to just one London custody suite". 24 July 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Incident response on the Tube to be boosted under 'Blue Light' trial". Transport for London. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Woodham, Peter (9 February 2012). "Blue light for Tube emergency teams". The Independent. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "BTP's rapid response vehicles get 'bluelights'". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Tube medic team cut after 'less conclusive' pilot - BBC News". BBC News. 16 December 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "7 July London bombings: Passenger safety recommendation dropped". BBC News. 4 July 2025.

- ^ "Emergency vehicle for faster response to railway incidents". Network Rail. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "Prestigious national award win". British Transport Police. 24 February 2015. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "Police and engineer partnership to cut delays". Rail Technology Magazine. 19 March 2013. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "Joint Emergency Response Unit launched in Scotland". British Transport Police. 31 July 2014. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- ^ "Medically trained police officers to patrol Tube network". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ "Medically trained BTP officers deployed on the Tube - Transport for London". Transport for London. 21 May 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Churchill, David. "Tube medical response team to be cut by more than half". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Green, David Allen. "Why are we arming the British Transport Police?". New Statesman. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Transport police to be armed to counter terror threat". BBC News. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ a b The Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP. "Provision of armed capability for the British Transport Police". Department for Transport (Press release). Archived from the original on 28 May 2011.

- ^ "BTP Firearms Capability". British Transport Police. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Firearms used by British Transport Police - Freedom of Information Request 794-14" (PDF). British Transport Police. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Armed response call outs - Freedom of Information Request 937-14" (PDF). British Transport Police. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Williams, Mark. "British Transport Police". Top Cover. The Police Firearms Officers Association Magazine. Vol. Spring 2013, no. 3. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 2014 c. 12

- ^ a b "Specialist firearms officers to patrol on trains as part of threat level change" (Press release). British Transport Police. 25 May 2017. Archived from the original on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Railways Act 1993 (c. 43)". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Transport and Works Act 1992 (c. 42)". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003 (c. 20)". Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "London Cable Car Order 2012". legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, s.100(2)

- ^ a b c d e "Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (c.24) – Statute Law Database". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (c.24) – Statute Law Database". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "ACPO Policing Protocol between BTP & Home Office Forces" (PDF). Library.college.police.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Channel Tunnel Act 1987". Statutelaw.gov.uk. 4 January 1995. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d "section 136, Criminal Justice & Public Order Act 1994". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Policing and Crime Act 2017". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "National and International Maritime Policing Powers- Policing and Crime Act 2017". Statutelaw.gov.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Infrastructure Act 2015".

- ^ "Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001". legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "Infrastructure Act 2015". Legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Infrastructure Act 2015". Legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "s18 Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003". Opsi.gov.uk. 10 July 2003. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Badges of rank". Archived from the original on 30 January 2021.

- ^ "Special Constables 2021 - British Transport Police".

- ^ "Police workforce, England and Wales: 31 March 2023". GOV.UK. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Ben Clifford [@BTPClifford] (21 September 2020). "I'm delighted to see that @BTPolFed have voted to allow @BTPSpecials to be members from January 2021 The federation does vital work support the welfare and representing our regular officers and it's good this will extend to our Special Constables too" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ BTP Federation [@BTPolFed] (14 September 2021). "It can be done and the reason for it is simple. Our Specials stand shoulder to shoulder with our regular officers and they also face the same risk and threats when on duty. As a federation we agreed that our Specials deserve the same protection as a regular officer. #OneBTP" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ British Transport Police [@BTP] (30 December 2011). "BTP Special Officers play a vital role alongside regular officers, facing the same risks and incidents on the network each day. That's why we're training a number of specials in England & Wales to be equipped with Taser to further protect both the public and frontline officers" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "Special Constable Ranks - BTP - a Freedom of Information request to British Transport Police". 24 December 2018.

- ^ "Special Constables". btp.police.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2026.

- ^ "Special Constables". btp.police.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2026.

- ^ "Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003". Legislation.gov.uk. 27 May 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "Archive collections". Btp.police.uk. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "> About us > History > Timeline". Archived from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "NPIA : PCSO Review July 2008" (PDF). Webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "S44/S60 Authorisations and PCSO powers. - a Freedom of Information request to British Transport Police". WhatDoTheyKnow.com. 4 December 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ "PCSO powers: Avon & Somerset - Leicestershire" (PDF). Webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "British Transport Police Recruitment - Transferring to BTP". www.btprecruitment.com. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Error" (PDF). www.btp.police.uk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Prison for £200,000 drug dealer". BBC News. 29 January 2010.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "About the police". U.K. Home Office. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

- ^ "About us". British Transport Police. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- ^ British Transport Police Authority (2012). "Millie Banerjee". BTPA website. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ^ "British Transport Police Authority board appoint new chair". Global Railway Review. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Department for Transport – Review of British Transport Police undertaken by DfT 2005–2006". Dft.gov.uk. 19 December 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- ^ "Scottish force to police railways". BBC News. 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Plans to merge British Transport Police with Police Scotland could be scrapped". Scotsman.com. 18 August 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ "Rail Value for Money Study : British Transport Police Review" (PDF). Orr.gov.uk. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

External links

[edit]British Transport Police

View on GrokipediaJurisdiction and Powers

Primary Jurisdiction Over Railways

The British Transport Police (BTP) serves as the dedicated national police force for the railway network across Great Britain, covering England, Scotland, and Wales, with primary jurisdiction focused on railway premises and operations.[9] This authority excludes Northern Ireland, where railway policing falls under local territorial forces. Enacted through the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003, BTP's mandate emphasizes preventing crime, ensuring safety for passengers and staff, and safeguarding railway infrastructure spanning over 10,000 miles of track and more than 3,000 stations.[10] [9] Section 31 of the 2003 Act delineates the precise scope of this jurisdiction, conferring upon BTP constables all powers and privileges of a constable within defined railway domains, including any track, railway network, station, light maintenance depot, siding, locomotive works, rolling stock, cable, or associated works.[11] This statutory framework establishes a comprehensive, self-contained railway jurisdiction throughout Great Britain, enabling officers to exercise full policing functions—such as arrest, search, and investigation—directly on these premises without reliance on territorial police extensions.[12] The focus remains on railway-specific threats, including trespass, vandalism, theft, and passenger assaults, with operational divisions aligned to major rail corridors to optimize response across the network.[1]Extended Powers and Limitations

British Transport Police (BTP) constables are endowed with the full powers and privileges of a constable within their statutory jurisdiction, which encompasses railway tracks, networks, stations, light maintenance depots, land used for or in connection with railways, and vehicles forming part of a railway service, extending throughout Great Britain for purposes connected with railways.[11] This jurisdiction, defined under section 31 of the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003, allows warrantless entry onto such property using reasonable force, irrespective of whether an offence is suspected.[11] These powers align with those of territorial constables under enactments such as the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984, enabling arrests, searches, and seizures tailored to transport security threats like theft, vandalism, and passenger safety incidents.[11] Beyond core railway premises, BTP officers may exercise constable powers outside their normal jurisdiction under three delineated conditions: when requested for assistance by a constable or authorized civilian; during fresh pursuit of a suspect from railway premises; or to prevent or mitigate loss of life, serious injury, or damage to property.[13] Section 100 of the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 further permits temporary extension of powers in response to terrorism-related risks, facilitating coordinated operations with territorial forces. However, such extensions are not routine; a policing protocol between BTP and Home Office forces stipulates that BTP should not be tasked with non-railway policing unrelated to transport networks, preserving their specialist focus amid resource constraints.[4] Limitations on BTP authority stem from their specialized remit, excluding general community policing responsibilities assigned to territorial forces; operations outside railway contexts require explicit triggers to avoid jurisdictional overreach.[13] In Scotland, while the 2003 Act confers equivalent powers, devolutionary pressures have prompted discussions on integration with Police Scotland, though BTP retains operational independence for rail matters as of 2025.[2] Funding reliance on rail industry levies, rather than general taxation, imposes fiscal limits on expansive jurisdiction claims, with the British Transport Police Authority enforcing strategic prioritization of transport-specific risks over broader societal issues.[14] Breaches of these bounds can lead to inter-force disputes, as evidenced by protocols mandating notification to local chief constables for extended exercises.[4]Mutual Aid and Cross-Border Operations

The British Transport Police (BTP) participates in national mutual aid protocols, allowing its officers to provide assistance to territorial police forces upon request from a chief constable, particularly for major incidents, public order events, or resource shortages outside the railway network. This arrangement is formalized in a 2002 protocol between BTP and local forces, which enables deployments while maintaining command structures under the requesting force.[15] Such aid aligns with broader National Police Chiefs' Council (NPCC) guidelines on mutual aid, updated annually to cover officer and staff deployments, cost recovery, and coordination for events like terrorism responses or civil unrest.[16] BTP's involvement extends to the Strategic Policing Requirement, where it contributes resources during national threats requiring surge capacity, as seen in mobilizations for public disorder in 2024.[17][18] Legal authority for these operations derives from the Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001, which grants BTP officers extended jurisdiction beyond railways under mutual aid or designated circumstances, such as protecting national infrastructure.[19] Outside mutual aid, BTP officers generally refrain from exercising full powers in non-transport areas to respect territorial force primacy, though seamless collaboration occurs through joint protocols, including with Scottish forces for recovery from serious incidents.[20] This framework ensures BTP's specialized rail expertise supports wider policing without jurisdictional overreach, with arrangements covering both routine assistance and international elements like aid to British Overseas Territories when applicable.[21] Cross-border operations reflect BTP's national remit over Great Britain's 10,000 miles of railway track, spanning England, Wales, and Scotland, where incidents on one network can cascade across administrative boundaries.[2] BTP collaborates with territorial forces in targeted initiatives, such as Operation Crossbow in March 2023, where over 200 officers from BTP, Cheshire Constabulary, and North Wales Police disrupted cross-border criminality exploiting rail and road networks for drug trafficking and theft.[22] Similar joint actions occurred in July 2023 across West Mercia and neighboring regions, focusing on denying criminals transport infrastructure access through proactive patrols and intelligence sharing.[23] In Scotland, BTP maintains distinct operations but coordinates via mutual aid for rail-linked threats, recognizing knock-on effects from cross-border routes like those to England.[24] These efforts underscore BTP's role in integrated policing, with formal and informal ties ensuring response efficacy across devolved jurisdictions.[25]Historical Development

Origins in the Railway Era

The expansion of railways in Britain during the early 19th century necessitated dedicated policing to safeguard passengers, freight, and infrastructure from theft, vandalism, and disorder, as general constabularies were insufficient for the novel challenges of linear transport networks spanning private land. The Stockton and Darlington Railway, opened in 1825 as the world's first public railway to use steam locomotives, employed police constables from that year to patrol tracks and prevent unauthorized access or sabotage, marking the initial ad hoc response to these risks.[26] By 1826, similar roles emerged on other lines, where men were tasked with "policing" the permanent way, though these were not yet formalized forces.[27] The first structured railway police establishment appeared in November 1830 with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, whose board minutes explicitly reference "The Police Establishment," predating the Metropolitan Police by nearly a year and establishing a model for subsequent companies.[28] Parliament granted each railway company statutory authority via private Acts to appoint constables with powers akin to borough watchmen, including arrest for offenses on company property, reflecting the causal link between privatized infrastructure and bespoke enforcement needs.[27] These forces grew rapidly; by the 1840s, major operators like the Great Western Railway (established 1835) and London and North Western Railway maintained dedicated officers focused on station security, ticket fraud prevention, and cargo protection, with numbers scaling to hundreds as mileage exceeded 6,000 miles by 1850.[26] Duties emphasized property protection over public order, driven by economic imperatives: railways transported high-value goods like coal and textiles, vulnerable to organized theft rings, while passenger volumes—reaching millions annually by mid-century—required crowd management amid industrial-era mobility. Incidents such as the 1830 Huskisson fatality at Manchester highlighted safety gaps, prompting formalized patrols.[29] Uniforms and organization varied by company, but common practices included plain-clothes detectives for fare evasion and uniformed patrols for visible deterrence, with oversight by company superintendents rather than external authorities. By the late Victorian period, over 100 separate forces existed, totaling around 1,500 officers, underscoring the fragmented yet effective adaptation to railway-specific threats before 20th-century consolidations.[26]Nationalization and Post-War Expansion

The nationalization of Britain's railways occurred on 1 January 1948 under the Transport Act 1947, which vested the assets of the "Big Four" railway companies—London, Midland and Scottish Railway, London and North Eastern Railway, Great Western Railway, and Southern Railway—in the newly established British Transport Commission (BTC).[30] This consolidation ended the era of fragmented private railway operations and their associated constabularies, which had policed tracks, stations, and rolling stock independently since the 19th century.[26] The BTC assumed responsibility for a unified national rail network spanning approximately 20,000 miles, alongside inland waterways, docks, and hotels, necessitating a centralized policing structure to maintain security and order across these expanded state-owned assets.[31] On 1 January 1949, the British Transport Commission Police was formally created through the amalgamation of the four principal railway police forces, along with smaller canal and dock constabularies, under the oversight of Chief Officer W.B. Richards.[32] This force, the second largest in the United Kingdom after the Metropolitan Police, inherited statutory powers derived from prior railway acts, which were consolidated and updated by the Transport Act 1949 to repeal outdated legislation and affirm constables' authority over transport premises.[33][34] The unification built on wartime precedents, where railway police had temporarily merged amid World War II disruptions, doubling their strength through recruitment of special constables and female officers to offset conscription losses.[35] Post-war expansion of the BTC Police reflected the broader recovery and modernization of Britain's transport infrastructure, with a reorganization on 1 April 1949 aligning divisions more closely with territorial police boundaries to enhance mutual aid and operational coordination.[30] The force's jurisdiction extended beyond railways to encompass BTC-managed docks and canals, addressing rising post-war passenger volumes—peaking at over 1.1 billion annually by the early 1950s—and associated crimes such as theft and vandalism amid economic austerity.[36] This period marked a shift from company-specific policing to a national entity equipped for systemic challenges, including labor disputes and sabotage risks inherited from wartime vulnerabilities, though chronic underfunding and recruitment difficulties persisted due to competitive pay relative to municipal forces.[33]Privatization Reforms and Modernization

The privatization of British Rail under the Railways Act 1993 fragmented the nationalized rail network into separate private train operating companies, infrastructure managers, and rolling stock lessors, prompting reforms to preserve unified policing across the divided system.[37] Sections 132 and 133 of the Act, along with Schedule 10, maintained the British Transport Police as a single national force responsible for railway premises and vehicles, avoiding the inefficiencies of fragmented local policing arrangements that could arise from territorial forces assuming jurisdiction.[38] This structural continuity ensured coordinated response to network-wide threats, such as vandalism or terrorism, despite the shift to over 25 train operating franchises by 1997.[37] Funding mechanisms transitioned from direct allocation by the state-owned British Railways Board to industry contributions, with train operators and later Network Rail required to fund police services through contractual agreements and a statutory levy calculated on factors like passenger miles and track access charges.[39] By 1996, as Railtrack assumed infrastructure control, this levy-based model stabilized BTP's budget at approximately £100 million annually in the late 1990s, tying fiscal accountability to rail performance while exposing the force to commercial pressures from operators seeking cost reductions.[40] Critics noted that this devolved funding risked underinvestment during low-traffic periods, though empirical data from the Office of Rail Regulation showed consistent levy collection supporting operational stability.[41] Subsequent modernization efforts culminated in the Railways and Transport Safety Act 2003, which established the independent British Transport Police Authority (BTPA) on 1 July 2004 to oversee strategy, performance, and complaints handling, replacing ad hoc committee governance with a statutory body comprising industry, user, and independent members.[14] The Act extended BTP jurisdiction beyond strict railway boundaries to adjacent public areas under police services agreements, enabling proactive patrolling at high-risk stations and enhancing response times, as evidenced by a 15% rise in detections for rail-specific offenses post-implementation.[42] These reforms emphasized evidence-based policing, integrating closed-circuit television networks expanded to over 10,000 cameras by 2005 and specialist units for counter-terrorism, funded partly through a £30 million capital injection in 2006 for headquarters and technology upgrades.[43]Recent Developments and Challenges

In 2024, British Transport Police (BTP) appointed Ian Drummond-Smith as Assistant Chief Constable for Network Policing, drawing from his 26-year tenure at Devon and Cornwall Police to bolster operational leadership amid rising demands.[44] This followed internal restructuring, including confirmation of Charlie Doyle as Network Policing lead in May 2024.[45] By August 2025, the force recruited a new Deputy Chief Constable to replace the incumbent, signaling efforts to stabilize senior command during fiscal strain.[46] BTP has confronted escalating crime volumes, with reported sexual harassment incidents surging 172% across the rail network from the year ending March 2023 compared to prior periods, per a February 2024 inspection by His Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services.[7] Crimes against staff reached 7,405 in the 2024-2025 period, marking an 8% year-on-year increase, exacerbating pressures on response capabilities.[47] The British Transport Police Authority's annual report for the year ending March 2024 highlighted persistent public sector funding constraints alongside multi-sector reforms, contributing to heightened operational demands without proportional resource growth.[48] A severe funding shortfall of £8.5 million for 2025-2026 has prompted a hiring freeze, potential closure of up to 13 stations, and risks to approximately 600 posts, including one in five civilian roles, threatening reduced frontline presence despite climbing assaults on passengers and rail workers.[49][50] Unions such as TSSA and RMT launched campaigns in May and August 2025, respectively, urging government intervention to avert cuts that could impair safeguarding of the network.[51] The force's reliance on industry levies, without central government grants afforded to territorial police, amplifies vulnerability to rail operator fiscal fluctuations, as noted in prior official responses to funding challenges.[39] The Police Federation expressed grave concerns in December 2024 over impacts on response times and community engagement from the latest settlement.[52]Governance and Funding

Oversight by the British Transport Police Authority