Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

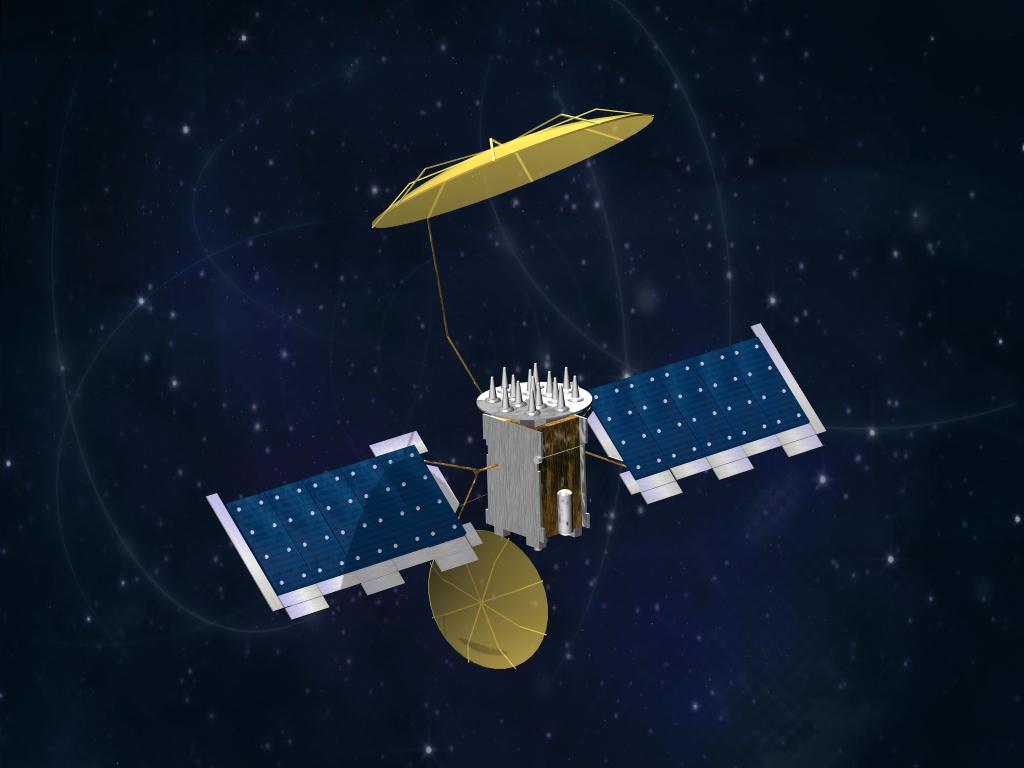

Mobile User Objective System

View on Wikipedia

The Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) is a United States Space Force narrowband military communications satellite system that supports a worldwide, multi-service population of users in the ultra high frequency (UHF) band. The system provides increased communications capabilities to newer, smaller terminals while still supporting interoperability with legacy terminals. MUOS is designed to support users who require greater mobility, higher bit rates and improved operational availability. The MUOS was declared fully operational for use in 2019.[1]

Overview

[edit]

The Mobile User Objective System (MUOS), through a constellation of five satellites (four operational satellites and one on-orbit spare), provides global narrowband connectivity to terminals, platforms, tactical operators and operations centers. The system replaces the slower and less mobile 1990s-era Ultra High Frequency Follow-On (UFO) satellite communication system. MUOS primarily serves the United States Department of Defense (DoD); although, international allies' use has been declined in the past.[2] Primarily for mobile users (e.g. aerial and maritime platforms, ground vehicles, and dismounted soldiers), MUOS extend users' voice, data, and video communications beyond their lines-of-sight at data rates up to 384 kbit/s.[3]

The U.S. Navy's Communications Satellite Program Office (PMW 146) of the Program Executive Office (PEO) for Space Systems in San Diego, is lead developer for the MUOS program.[4] Lockheed Martin Space is the prime system contractor and satellite designer for MUOS under U.S. Navy Contract N00039-04-C-2009, which was announced on 24 September 2004.[5][6] Key subcontractors include General Dynamics Mission Systems (Ground Transport architecture), Boeing (Legacy UFO and portions of the WCDMA payload) and Harris (deployable mesh reflectors). The program delivered five satellites, four ground stations, and a terrestrial transport network at a cost of US$7.34 billion.[7]

Each satellite in the MUOS constellation carries two payloads: a legacy communications payload to maintain Department of Defense narrowband communications during the transition to MUOS, and the advanced MUOS Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (WCDMA) capability, according to Naval Information Warfare Systems Command (NAVWAR).

WCDMA system

[edit]MUOS WCDMA radios can transmit simultaneous voice, video and mission data on an Internet Protocol-based system connected to military networks. MUOS radios operate from anywhere around the world at speeds comparable to 3G smartphones. MUOS radios can also work under dense cover, such as jungle canopies and urban settings. The MUOS operates as a global cellular service provider to support the warfighter with modern cell phone-like capabilities, such as multimedia. It converts a commercial third generation (3G) Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (WCDMA) cellular phone system to a military UHF SATCOM radio system using geosynchronous satellites in place of cell towers. By operating in the Ultra high frequency (UHF) frequency band, a lower frequency band than that used by conventional terrestrial cellular networks, the MUOS provides warfighters with the tactical ability to communicate in "disadvantaged" environments, such as heavily forested regions where higher frequency signals would be unacceptably attenuated by the forest canopy. Connections may be set up on demand by users in the field, within seconds, and then released just as easily, freeing resources for other users. In alignment with more traditional military communications methods, pre-planned networks can also be established either permanently or per specific schedule using the MUOS' ground-based Network Management Center.

Legacy payload

[edit]In addition to the cellular MUOS WCDMA payload, a fully capable and separate UFO legacy payload is incorporated into each satellite. The "legacy" payload extends the useful life of legacy UHF SATCOM terminals and enables a smoother transition to MUOS.

Launches

[edit]MUOS-1, after several weather delays, was launched into space successfully on 24 February 2012, at 22:15:00 UTC, carried by an Atlas V launch vehicle flying in its 551 configuration.[8]

MUOS-2 was launched on schedule on 19 July 2013, at 13:00:00 UTC aboard an Atlas V 551 (AV-040).[9]

MUOS-3 was launched on board a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V launch vehicle on 20 January 2015, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Florida.[10][11]

MUOS-4 arrived at Cape Canaveral on 31 July 2015.[12] Weather conditions pushed back the launch, which was originally scheduled for on 31 August 2015, at 10:07 UTC.[13][14] The launch took place on 2 September 2015, at 10:18:00 UTC.[15]

MUOS-5 arrived at Cape Canaveral on 9 March 2016.[16] Launch was originally scheduled for on 5 May 2016, but due to an internal investigation into an Atlas V fuel system problem during the Cygnus OA-6 launch on 22 March 2016, the scheduled date was pushed back.[17] The launch took place on 24 June 2016, at 14:30:00 UTC.[18] An "anomaly" aboard the satellite occurred a few days later, however, when it was still in a Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO), leaving it "Reconfigured into Safe Intermediate Orbit", or stranded in GTO.[19][20] Amateur observers tracked it in an orbit of approximately 15,240 × 35,700 km (9,470 × 22,180 mi) since 3 July 2016.[21] On 3 November 2016, the Navy announced that the satellite has finally reached operational orbit.

MUOS operational positions

[edit]The four currently operational MUOS satellites are stationed at longitude 100° West (MUOS-1); 177° West (MUOS-2); 16° West (MUOS-3); and 75° East (MUOS-4).[22] MUOS-5 is a spare satellite now orbiting over the Continental US. They have a 5° orbital inclination. In the first few months after launch, the satellites were temporarily parked in a check-out position at longitude 172° West.[23]

MUOS ground stations

[edit]

The MUOS includes four ground station facilities.[3] Site selections were completed in 2007 with the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) between the U.S. Navy and the Australian Department of Defence. The four ground stations, each of which serves one of the four active satellites of the MUOS constellation will be located at: the Australian Defence Satellite Communications Station at Kojarena, Western Australia about 30 km east of Geraldton, Western Australia; Naval Radio Transmitter Facility (NRTF) Niscemi about 60 km from Naval Air Station Sigonella, Sicily, Italy; Naval SATCOM Facility, Northwest Chesapeake, Southeast Virginia at 36°33′52″N 76°16′14″W / 36.564393°N 76.270477°W; and the Naval Computer and Telecommunications Area Master Station Pacific, Hawaii.

Controversy

[edit]Construction of the ground station in Italy was halted for nearly half of 2012 by protesters concerned with health risks and environmental damage by radio waves. One scientific study "point[s] to serious risks to people and the environment, such as to prevent its realization in densely populated areas, like the one adjacent to the town of Niscemi".[24] In spite of the controversy, the site at Niscemi was completed in anticipation of the launch of MUOS-4.

Radio terminals

[edit]The MUOS waveform with complete red/black operational capability was released in 2012. Until the Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) program cancellation in 2011, the JTRS program would provide the DoD terminals that can communicate with the MUOS WCDMA waveform with a series of form-factor models. The JTRS Handheld, Manpack and Small Form Fit (HMS) AN/PRC-155 manpack built by General Dynamics Mission Systems survived the wider JTRS program cancellation and has shipped several low rate of initial production (LRIP) units. Rockwell Collins AN/ARC-210[25][26] airborne terminal and Harris Corporation AN/PRC-117G.[27][28] Manpack have also been certified for operation on the MUOS system.

Arctic and Antarctic capabilities

[edit]Lockheed Martin and an industry team of radio vendors demonstrated extensive Arctic communications reach near the North Pole, believed to be the most northerly successful call to a geosynchronous satellite.[29] WCDMA calls to the far north will be increasingly important where there has been an increase in shipping, resource exploration and tourism without much improvement in secure satellite communications access. Based on these and continued tests, full coverage of the Northwest Passage and Northeast Passage shipping lanes is expected. Several follow-on tests with high quality voice and data including streaming video have occurred in both the Arctic and Antarctic, including a 2015 demonstration from McMurdo Station.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "U.S. Navy declares MUOS satcom system ready for full operational use". Naval Technology. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Allies' Access to MUOS Debated after North Pole Satcom Demo". SpaceNews. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Military Communications Satellite System, Multiplies UHF Channel Capacity for Mobile Users" (PDF). Telcordia. 27 February 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Fact Sheet, Navy Communications Satellite Programs, Ultra High Frequency Follow-On (UFO) Program" (PDF). US Navy. 1 March 1999. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command Awards Contract" (PDF). SPAWAR. 24 September 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ DoD Contract Awards for September 24, 2004

- ^ "Report to Congressional Committees, Defense Acquisitions, Assessments of Selected Weapon Programs" (PDF). U.S. Government Accountability Office. March 2013. pp. 99–100. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Atlas V finally launches with MUOS – Centaur celebrates milestone". NASASpaceFlight.com. 24 February 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "ULA Atlas V launches with MUOS-2 satellite". NASASpaceFlight.com. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "US Navy prepares for third MUOS satellite launch". Naval Technology. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "ULA Atlas V successfully launches third MUOS spacecraft". NASASpaceFlight.com. 20 January 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Navy's MUOS-4 Shipped for August Launch". SpaceNews. 1 July 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "Tropical weather threatens Monday's scheduled Atlas 5 launch". Spaceflight Now. 28 August 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "Counting Down: U.S. Navy, Lockheed Martin Ready to Launch MUOS-4 Secure Communications Satellite August 31". Lockheed Martin. 28 August 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "Live coverage: Atlas 5 countdown and launch journal". Spaceflight Now. 2 September 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "MUOS 5 satellite comes to Florida on way to geosynchronous orbit". Spaceflight Now. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ "New target date for next Atlas 5 launch". Spaceflight Now. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ^ Gruss, Mike (24 June 2016). "Atlas V returns to flight with launch of Navy's MUOS-5". SpaceNews. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "MUOS-5 Transfer Maneuver Temporarily Halted, Satellite Reconfigured into Safe Intermediate Orbit". United States Navy. 8 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Ray, Justin (8 July 2016). "Navy's new MUOS-5 communications satellite experiences snag in space". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ Langbroek, Marco (8 July 2016). "MUOS-5 stuck in GTO". SatTrackCam Leiden (b)log. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ "J.D. Oetting and Tao Jen: The Mobile User Objective System. Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest 30:2 (2011)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ "MUOS-4 at its 172 W check-out location". sattrackcam.blogspot.com. 25 September 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ Risk Analysis Turin University

- ^ ARC-210 successfully completes first inflight MUOS tests on 19 November 2013

- ^ Rockwell Collins ARC-210 becomes first airborne radio to operate on MUOS satellite system Oct. 1, 2014

- ^ Harris Corporation Falcon III Manpack Radio Successfully Communicates with MUOS Satellite Constellation December 2, 2013

- ^ Harris Corporation Continues Successful Demonstrations of Falcon III Manpack Radio with Mobile User Objective System April 24, 2014

- ^ Lockheed Martin MUOS Satellite Tests Show Extensive Reach in Polar Communications Capability

- ^ Researchers take high-bandwidth communications to the South Pole

External links

[edit]- [1] MUOS 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

- Oetting, John D.; Jen, Tao (2011). "The Mobile User Objective System" (PDF). Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest. 30 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

Mobile User Objective System

View on GrokipediaDevelopment and Program History

Origins and Strategic Requirements

The Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) originated as a U.S. Navy-led initiative to address the limitations of the legacy Ultra High Frequency (UHF) Follow-On (UFO) satellite constellation, which had been providing narrowband military satellite communications since the late 1990s but was nearing end-of-life and struggling with capacity constraints for expanding mobile user demands.[5][6] Strategic requirements were driven by the Department of Defense's shift toward joint-service operations emphasizing mobile tactical forces, necessitating beyond-line-of-sight, secure communications capable of supporting higher data rates, greater user mobility, and improved operational availability in contested environments.[7] These needs arose from operational experiences requiring reliable penetration of foliage, urban terrain, and adverse weather, while integrating with IP-based networks for voice, video, and data transmission to tens of thousands of terminals.[8] Early development traced to an analysis of alternatives completed in 2001 by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, which informed the adoption of Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (WCDMA) technology to achieve over tenfold capacity increases compared to UFO satellites, with data rates ranging from 2.4 kbps to 384 kbps.[8] The program's core objectives included global coverage from 65° N to 65° S latitude, support for a worldwide multi-service population of mobile users, and jam-resistant narrowband SATCOM to sustain tactical operations without reliance on terrestrial infrastructure.[7][5] This addressed the UFO's single-channel-per-carrier limitations, which could not scale to the projected growth in user endpoints exceeding 200,000.[7] Formal program advancement followed with a $2 billion contract award to Lockheed Martin on September 24, 2004, establishing MUOS as the next-generation system to ensure continuity of critical communications for U.S. forces in humanitarian, disaster response, and combat scenarios.[9] The design incorporated dual payloads per satellite—legacy UHF for backward compatibility and modern WCDMA for enhanced throughput—reflecting requirements for seamless transition while prioritizing survivability and spectral efficiency against interference.[10][8]Key Contracts and Contractors

Lockheed Martin Space Systems Company, based in Sunnyvale, California, serves as the prime contractor and lead system integrator for the Mobile User Objective System (MUOS), responsible for designing and building the satellite constellation leveraging its A2100 satellite bus platform.[9][11] In September 2004, the U.S. Navy awarded Lockheed Martin a $2 billion fixed-price-incentive contract (N00039-04-C-2009) to develop the MUOS, covering the initial two satellites with options for up to five, emphasizing integration of wideband code division multiple access (WCDMA) technology for enhanced narrowband communications.[9][12] Subsequent modifications included a $92.8 million increase in March 2019 for engineering and logistics support on the ground segment, raising the contract ceiling to sustain operations amid deployment challenges.[13] General Dynamics Mission Systems acts as a key subcontractor for the MUOS ground infrastructure, including development and sustainment of the radio access facilities and network management systems.[11] In November 2019, the U.S. Navy granted General Dynamics a $731.8 million cost-plus-award-fee and firm-fixed-price indefinite delivery/indefinite quantity contract over 10 years for post-deployment sustainment, ensuring operational readiness of the end-to-end system for secure voice and data services.[14] This sole-source award built on General Dynamics' prior role in ground terminal integration, addressing compatibility with legacy ultra-high frequency (UHF) payloads.[15] Other notable subcontractors include Harris Corporation (now L3Harris Technologies), contributing to waveform development and terminal equipment for interoperability between MUOS and legacy systems.[11] The program's structure relied on a consortium model, with Lockheed Martin coordinating these partners to mitigate risks in adopting commercial cellular-derived technology for military narrowband needs, though integration complexities contributed to later cost overruns exceeding initial estimates by billions.[9][12]| Contractor | Role | Key Contract Value and Date |

|---|---|---|

| Lockheed Martin Space Systems | Prime contractor; satellite design, build, and integration | $2 billion (September 2004); $92.8 million modification (March 2019)[9][13] |

| General Dynamics Mission Systems | Ground segment development and 10-year sustainment | $731.8 million (November 2019)[14] |

| Harris Corporation | Waveform and terminal interoperability support | Integrated within prime consortium (2004 onward)[11] |

Program Delays, Costs, and Management Challenges

The Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) program experienced significant schedule delays stemming from technical complexities in spacecraft development and waveform integration. The launch of the first satellite slipped from March 2010 to February 2012, a two-year delay attributed to budget reallocations for operations in Iraq and subsequent engineering challenges.[16][17] Further delays affected subsequent satellites, including a six-month postponement for MUOS-3 due to a soldering defect discovered in 2014, pushing its launch to January 2015.[18][17] Operational testing was deferred by 17 months to November 2015, while fielding of compatible Army radios shifted from 2014 to 2016, largely due to persistent issues with the wideband code division multiple access (WCDMA) waveform software reliability.[17][19] Additional setbacks included legal challenges rendering the Niscemi, Italy, radio access facility non-operational and ongoing deferrals of geolocation capabilities to fiscal year 2018 follow-on testing.[5] Program costs saw substantial growth early in development, with satellite-related issues driving a 48 percent increase over initial estimates as reported by the U.S. Government Accountability Office in 2009.[20] The original total program acquisition cost stood at approximately $8.2 billion, though later revisions brought the current estimate down to $7.6 billion through scope adjustments and efficiencies, avoiding net overruns relative to the revised baseline.[17] Terminal development and ground system upgrades contributed to elevated expenses, including high depot support demands—averaging 90 visits over 20 test days—and cessation of funding for performance modeling in 2014 as a cost-avoidance step.[5] Replenishment satellites for the constellation are projected at $1.4 billion each in then-year dollars, reflecting parts obsolescence and non-recurring engineering needs.[12] Management challenges exacerbated these issues, including poor inter-stakeholder communications that hindered progress on satellite programs like MUOS, as noted by Lockheed Martin executives.[20] Integration of the MUOS waveform proved particularly problematic, leaving satellites underutilized and reliant on legacy systems for over 90 percent of capabilities during early operations.[17][19] Ground system software accumulated over 900 unresolved problem change requests by 2016, with high-priority items averaging 526 days old, compounded by inadequate training, documentation gaps affecting 38 percent of trouble tickets, and ineffective fault management leading to cryptic alerts and prolonged repair times—median network management system repairs took 89 hours against a 45-minute threshold.[5] Cybersecurity vulnerabilities exceeded 1,000, with half rated Category II or higher, while limited user engagement in software-intensive phases delayed synchronization of radios, ground stations, and satellites.[5][21] These factors, alongside contractor turnover and restricted access to operational controls, underscored systemic difficulties in prioritizing and resolving issues across the Department of Defense acquisition process.[5]Technical Architecture

Satellite Constellation Design

The MUOS satellite constellation consists of five satellites in geosynchronous Earth orbit (GEO): four operational satellites and one on-orbit spare.[1][12] These satellites are positioned in the near-equatorial plane with low inclinations, typically around 5 degrees or less, to optimize visibility over the primary coverage zone extending from 65° N to 65° S latitudes.[22][5] This configuration provides near-continuous coverage across more than 70% of the Earth's surface pertinent to global military operations, with dual satellite visibility in equatorial and mid-latitude regions to support load sharing and redundancy.[23][24] The operational satellites are longitudinally spaced to ensure overlapping footprints, generally separated by approximately 90 degrees to achieve global non-polar coverage without gaps in service.[24] Specific slots have included positions such as 75° E for certain satellites during operational phases, with adjustments made post-launch to refine coverage based on mission requirements and interference avoidance.[25] The on-orbit spare is maintained in a compatible GEO slot, enabling rapid repositioning if an active satellite fails, thereby preserving system availability.[1] This resilient architecture addresses the limitations of legacy systems like the UHF Follow-On constellation by distributing capacity more efficiently across the operational envelope.[5] Each satellite in the constellation is engineered for a minimum 15-year service life, with the design incorporating propulsion systems for station-keeping and orbit maintenance against GEO perturbations.[16] The constellation's overall capacity is enhanced such that a single MUOS satellite delivers four times the throughput of the entire preceding eight-satellite legacy UHF fleet, underscoring the efficiency gains from the optimized spatial arrangement and payload advancements.[26] As of February 2025, the five-satellite setup continues to form the backbone of MUOS operations, with ongoing service life extension efforts targeting additional units to extend capabilities into the 2030s.[3]WCDMA-Based Communication System

The Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) implements a Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (WCDMA) communication architecture adapted from commercial third-generation (3G) cellular standards, enabling high-capacity narrowband satellite communications in the ultra-high frequency (UHF) band. This waveform, known as spectrally adaptive WCDMA (SA-WCDMA), operates within a 20 MHz allocation, utilizing 5 MHz channels to support data rates from 2.4 kbps up to 384 kbps for voice, video, and data services.[27][24] The system relays user signals via geosynchronous satellites to one of four ground stations—located in Wahiawa, Hawaii; Landstuhl, Germany; Niscemi, Italy; and Geraldton, Australia—before routing through an IP-based core network.[12] Developed by General Dynamics Mission Systems, the MUOS WCDMA waveform incorporates power control and spread-spectrum techniques to coexist with legacy UHF frequency-division multiple access (FDMA) and time-division multiple access (TDMA) users in the shared 225–400 MHz UHF SATCOM spectrum, minimizing interference and performance degradation for both.[26][24] Each MUOS satellite carries a dedicated WCDMA payload alongside a legacy UHF payload, allowing seamless backward compatibility; the WCDMA subsystem processes signals using baseband processing for dynamic resource allocation, prioritization of critical traffic, and quality-of-service management akin to terrestrial cellular networks.[11] This design supports thousands of simultaneous users per satellite, representing a capacity increase of approximately 10- to 16-fold over prior UHF constellations, with a single MUOS satellite providing four times the throughput of the entire legacy eight-satellite UFO/UHFS network.[1][28][29] The WCDMA implementation adheres to 3GPP standards but includes satellite-specific adaptations, such as half-duplex constraints and resilience features to handle propagation delays and beamforming across global coverage areas.[30] Operational testing has demonstrated superior message accuracy and service quality compared to legacy UHF under nominal conditions, though the system lacks proactive failure monitoring for WCDMA links, potentially leading to extended outages without user notification.[5][10] User terminals, including Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) variants like the AN/PRC-155 manpack, interface via the WCDMA waveform to enable mobile, on-the-move communications with cellular-like features such as handover between satellite beams.[26]Legacy UHF Payload Integration

Each Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) satellite integrates a separate legacy Ultra High Frequency (UHF) payload designed to replicate the capabilities of a single UHF Follow-On (UFO) satellite, ensuring backward compatibility with existing legacy UHF satellite communications (SATCOM) terminals and infrastructure.[31] This payload operates independently from the primary Wideband Code Division Multiple Access (WCDMA) payload, without interconnection between the two, to maintain isolation between modern network-centric communications and traditional UHF services.[32] The inclusion of this legacy component addresses the need to sustain UHF SATCOM capacity as the aging UFO constellation approaches end-of-life, preventing service gaps for users reliant on narrowband legacy systems.[8] The legacy UHF payload supports standard 5 kHz and 25 kHz channelized voice, data, and telemetry services compatible with deployed terminals, enabling MUOS to function as a direct supplement to UFO satellites during the transition period.[33] Boeing's Integrated Defense Systems provided the legacy UHF payloads for the MUOS constellation, integrating them onto the Lockheed Martin-built satellite bus alongside the WCDMA system developed by General Dynamics.[16] Pre-launch testing, including end-to-end demonstrations in 2009 and 2011, verified seamless interoperability with legacy UHF ground terminals, confirming that MUOS satellites could handle both payload types simultaneously without disrupting established UHF operations.[34][35] This dual-payload architecture facilitates a phased migration to MUOS capabilities, as military services upgrade select terminals for WCDMA access while preserving full support for unmodified legacy equipment, thereby extending the operational lifespan of thousands of existing UHF assets across U.S. Department of Defense platforms.[36] The legacy payload's capacity equates to that of one UFO satellite per MUOS unit, contributing to overall constellation redundancy and reliability for narrowband SATCOM demands in contested environments.[31]Launches and Orbital Deployment

Satellite Launch Timeline

The Mobile User Objective System (MUOS) constellation consists of five satellites launched between 2012 and 2016 aboard United Launch Alliance Atlas V rockets from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.[16] Each launch followed a rigorous pre-flight preparation process, including payload integration and environmental testing at the Astrotech Space Operations facility.[16] The first satellite, MUOS-1, lifted off on February 24, 2012, at 22:15 UTC, marking the initial deployment of the next-generation narrowband satellite communications system designed to replace the legacy UHF Follow-on (UFO) constellation.[16] MUOS-2 followed on July 19, 2013, at 07:52 UTC, providing redundancy and expanding coverage capabilities.[16] MUOS-3 launched on January 20, 2015, at 20:43 UTC, after weather-related delays, and entered service after on-orbit checkout.[16][37] MUOS-4 was launched on September 2, 2015, at 10:18 UTC, following a two-day postponement due to tropical weather conditions, and completed initial testing before operational acceptance by the U.S. Navy in November 2015.[38] The final satellite, MUOS-5, deployed as an on-orbit spare on June 24, 2016, at 14:30 UTC, completing the five-satellite network intended for global, high-capacity communications.[16]| Satellite | Launch Date | Launch Vehicle | NORAD ID | Status Post-Launch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUOS-1 | February 24, 2012 | Atlas V 551 | 2012-009A | Operational after checkout[16] |

| MUOS-2 | July 19, 2013 | Atlas V 551 | 2013-036A | Operational[16] |

| MUOS-3 | January 20, 2015 | Atlas V 551 | 2015-002A | Operational[16] |

| MUOS-4 | September 2, 2015 | Atlas V 551 | 2015-044A | Operational[16] |

| MUOS-5 | June 24, 2016 | Atlas V 501 | 2016-041A | On-orbit spare, propulsion anomaly during orbit raising[16][1] |