Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

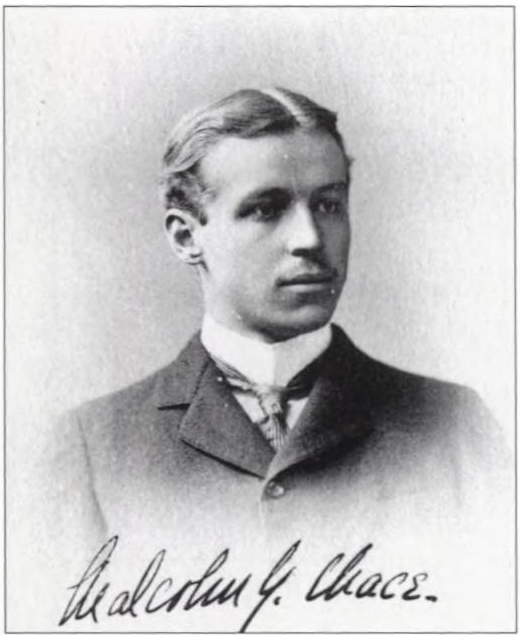

Malcolm Greene Chace

View on Wikipedia

Malcolm Greene Chace (March 12, 1875 – July 16, 1955) was an American financier and textile industrialist who was instrumental in bringing electric power to New England.[1] He was a pioneer of the sport of ice hockey in the United States, and was Yale University's first hockey captain. He was also an amateur tennis player whose highest ranking was U.S. No. 3 in 1895.

Key Information

Personal life

[edit]Chace was born March 12, 1875, in Central Falls, Rhode Island[1] into the illustrious Chace family. Malcolm's great-grandfather Oliver Chace was a textile mill owner, whose company later became Berkshire Hathaway. His grandmother was anti-slavery activist Elizabeth Buffum Chace. His parents were Brown University chancellor Arnold Buffum Chace and Eliza Greene Chace. His son, Malcolm Greene Chace, Jr. and grandson Malcolm Greene Chace III also became directors of Berkshire Hathaway.

Chace briefly attended Brown University, but transferred to Yale and graduated from Yale's Sheffield Scientific School in 1896, attaining some fame as a tennis player at both schools.[1] In 1914, he purchased Point Gammon Light on Great Island in West Yarmouth, Massachusetts, which had previously been owned by the renowned ornithologist Charles Barney Cory. By 1925, Chace owned the entire island, the majority of which has remained in the Chace family to the present day.[3][4] Chace lived for some time in Providence, Rhode Island, but spent the last 10 years of his life at 60 Sutton Place in New York City and at his summer home in Hyannis, Massachusetts.[1]

Chace's first wife Elizabeth Edwards died in 1947. His second wife Kathleen Dunster (incorrectly reported in his New York Times obituary as "Kathleen Dunbar"),[5] outlived him.[1] He had two sons (Malcolm Greene Chace, Jr. and Arnold B. Chace III) and three daughters.

"Father of ice hockey in the United States"

[edit]According to his obituaries, Chace was "credited with having been the father of hockey in the United States."[1][5][6] In fall 1892, while still a student at Brown University, Chace visited Niagara Falls, Ontario, for a tennis tournament.[7] While there, Chace was introduced to ice hockey by members of the Victoria Hockey Club.[8][1] During Christmas Break 1894-95 Chace put together a team of men from Yale, Brown, and Harvard, and Columbia[8] and played ten (or five?[7]) games, touring Montreal, Kingston, Ottawa and Toronto as captain of this team, with the goal of learning how to play the Canadian game of hockey.[1][5] Upon their return, each of the students established hockey clubs at their respective schools.[8] Chace transferred from Brown to Yale, where he served as team captain and also the player-coach.[7]

On February 14, 1896, played in the first intercollegiate hockey match in the United States against Johns Hopkins University at Baltimore's North Avenue Rink. Yale won the game, 2–1, and both goals were scored by Chace.[9][10]

Chace played on various other hockey teams over a decade-long career, including the St. Nicholas Hockey Club in New York.[5] He was one of the financial backers of New York's St. Nicholas Rink.[5] In 1932, Chace rescued the Rhode Island Auditorium, then Providence's professional and amateur hockey arena, from foreclosure.[6]

In 2018, the Rhode Island Hockey Hall of Fame and the Chace family established the Malcolm Greene Chace Memorial Trophy to be presented each year for "Lifetime contributions of a Rhode Islander to the game of ice hockey". In 2019, Chace was enshrined in the RI Hockey Hall of Fame.

To honor Chace, Yale created an award in his name, and in 1998 created the position of Malcolm G. Chace Head Hockey Coach.[9] Tim Taylor was the first Yale coach to serve with this title.[9] A portrait of Chace hangs in the Schley Room at Ingalls Rink.[9]

Tennis career

[edit]Chace's tennis career started in his childhood. At age 14 he became Rhode Island's youngest state tennis champion, and four times he placed among the top ten amateur tennis players.[5] He was national college champion in 1893, 1894, and 1895.[5]

Malcolm played for both Brown University and Yale while still a student.[1] When he graduated from Yale in 1896, he retired from tennis, but not before setting a record by winning the U.S. Intercollegiate Singles and Doubles titles for three consecutive years (1893–1895).[11] In 1893 he won the Narragansette Pier Open against Bill Larned.

In July 1894, he won the Tuxedo tournament in New York City defeating Clarence Hobart in the final in five sets.[12] He successfully defended his title the following year when he was victorious against future seven-time U.S. Championship winner Bill Larned in straight sets.[13]

Chace won the U.S. National Doubles Championship in 1895 and was a doubles finalist in 1896, in both cases partnering compatriot Robert Wrenn.[14] In singles, he reached the semifinals in 1894 and the quarterfinals in 1895 and 1900.

Chace was inducted in the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1961.[6]

Grand Slam finals

[edit]Doubles (1 title, 1 runner-up)

[edit]| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Partner | Opponents | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Win | 1895 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 7–5, 6–1, 8–6 | ||

| Loss | 1896 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 3–6, 6–1, 1–6, 6–3, 1–6 |

Industrial career

[edit]Electric power

[edit]Shortly after graduating college, Chace became associated with the introduction of electric power to New England.[1] By 1910 he formed the firm of Chace & Harriman, which built a 24,000 kilowatt power plant on the Connecticut River near Brattleboro, Vermont.[1] Eventually Chace helped develop the New England Power Association and in 1926 he gained control of the Narragansett Electric Lighting Company.[1] In his obituary, the Providence Journal said Chace had been "one of the most influential men in the development of electric power in the Northeast."[1]

Textile mills

[edit]In 1926, Chace formed the Berkshire Fine Spinning Associates, Inc, the largest producer of fine cotton goods in the United States.[1] It had mills in Albion, Warren, Anthony, and Fall River.[1] This company later became known as Berkshire Hathaway.[1] He was also president of the Fort Dummer textile mill in Brattleboro, Vermont.

Oil tankers

[edit]During World War I and "most of" World War II, Chace maintained a fleet of tankers to transport oil to New England.[1] It was the largest independent oil tanker fleet in the US.[1][5]

Death and burial

[edit]

Chace died July 16, 1955 (aged 80) at his summer home in Hyannis, Massachusetts[1] and is buried at Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, Rhode Island.[2]

Legacy

[edit]- Chace was inducted in the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1961.[6]

- Yale University created the Malcolm G. Chace Award, which is given each year to the player who "best exemplifies leadership and the traditions of the sport at Yale."[9]

- In 1998 Yale established the position of Malcolm G. Chace Head Hockey Coach.[9] Tim Taylor was the first Yale coach to serve with this title.[9]

- A portrait of Chace hangs in the Schley Room at Ingalls Rink.[9]

- The Malcolm Greene Chace Memorial Trophy was established in 2018 to honor “Achievement and Outstanding Service by a Rhode Islander to the Game of Hockey.”[8]

- Chace was inducted into the Rhode Island Hockey Hall of Fame in 2019.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Malcolm G. Chace, 80, Industrial Leader, Dies". Vol. LXXL, no. 3. Providence, RI: The Providence Sunday Journal. July 17, 1955. p. 24.

- ^ a b "Burial Information". Swan Point Cemetery. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Point Gammon, MA". Lighthouse Friends.

- ^ Snell, Bob (June 11, 1987). "Subdividing to protect Yarmouth's Great Island". Yarmouth Register. Yarmouth, MA. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "MALCOLM CHACE, FINANCIER, DIES". The New York Times. July 17, 1955. p. 61. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

credited with being the father of hockey in the United States

- ^ a b c d "Rhode Island Hockey Hall of Fame". Rhode Island Hockey Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ a b c Hanlon, John (April 17, 1967). "When Harvard Met Brown It Wasn't Ice Polo". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

A lot of weird games between a lot of scrub teams probably were played on ice before Jan. 19, 1898, but on that day modern intercollegiate hockey competition was officially born

- ^ a b c d "Malcolm Greene Chace Memorial Trophy". Rhode Island Hockey Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Position as Malcolm G. Chace Hockey Coach Inaugurated At Yale's Ingalls Rink in Honor of U.S. Hockey Founder". March 12, 1998.

- ^ "Yale 2; Hopkins 1: An Exciting Game of Hockey at the Rink". The Baltimore Sun. February 15, 1896. p. 6.

- ^ "Chace The Champion" (PDF). The New York Times. October 7, 1893.

- ^ "Chace Won the Cup" (PDF). The New York Times. July 8, 1894.

- ^ "Chace Outplays Larned" (PDF). The New York Times. July 9, 1895.

- ^ Collins, Bud (2010). The Bud Collins History of Tennis (2nd ed.). [New York]: New Chapter Press. p. 476. ISBN 978-0942257700.

External links

[edit]- Malcolm Greene Chace at the International Tennis Hall of Fame

- Malcolm Greene Chace at the Tennis Archives