Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Malt house

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A malt house, malt barn, or maltings, is a building where cereal grain is converted into malt by soaking it in water, allowing it to sprout and then drying it to stop further growth. The malt is used in brewing beer, whisky and in certain foods. The traditional malt house was largely phased out during the twentieth century in favour of more mechanised production. Many malt houses have been converted to other uses, such as Snape Maltings, England, which is now a concert hall.

Production process

[edit]Floor malting

[edit]The grain was first soaked in a steeping pit or cistern for a day or more. This was constructed of brick or stone, and was sometimes lined with lead. It was rectangular and no more than 40 inches (100 cm) deep. Soon after being covered with water, the grain began to swell and increase its bulk by 25 percent.[1]

The cistern was then drained and the grain transferred to another vessel called a couch, either a permanent construction, or temporarily formed with wooden boards. Here it was piled 12–16 inches (30–41 cm) deep, and began to generate heat and start to germinate. It spent a day or two here, according to the season and the maltster's practice.[1]

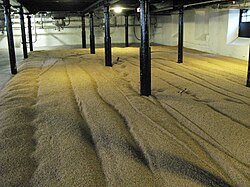

It was then spread out on the growing floor, the depth dictated by the temperature, but sufficiently deep to encourage vegetation. It was turned at intervals to achieve even growth and over the next fourteen days or so it is turned and moved towards the kiln. The temperature was also controlled by ventilation. A day or two after the grain was turned out on to the floor, an agreeable smell was given off, and roots soon began to appear. A day or so later the future stem began to swell, and the kernel became friable and sweet-tasting. As the germination proceeded the grain was spread thinner on the floor. The process was halted before the stem burst the husk. At this stage much of the starch in the grain had been converted to maltose and the grain was left on the floor to dry. The art of malting depends on the proper regulation of these changes in the grain. Maltsters varied in their manner of working, and adapted to changes in climatic conditions.[1][2]

The grain was then moved into the kiln, 4–6 inches (10–15 cm), for between two and four days, depending on whether a light or dark malt was required. A slow fire was used to start, and then gradually raised to suit the purpose of the malt and the desired colour. The barley was then sieved to remove the shoots and stored for a few months to develop flavour.[1][2]

Saladin malting

[edit]

The Saladin system of mechanical and pneumatic malting was designed for a high performance process. The inventor Charles Saladin was a French engineer. The barley is soaked for an hour to remove swimming barley. This is followed by two hours of soaking to remove attached particles and dust. The next step is a prewashing by water circulation for 30 minutes followed by washing with fresh water and removing the overfall. A dry soak with CO2 exhaustion during 4 hours follows. Several dry and wet soaking steps are to follow. The last step is the transfer to the saladin box.

Steep, germinate and kilning vessel

[edit]While in the traditional malt houses the product flow is horizontal, the flow in the Steep, Germinate and Kilning Vessel is vertical. Due to high capital costs this process is used only in industrial maltings for beer malt.

In the United Kingdom

[edit]

Many villages had a malt house in the eighteenth century, supplying the needs of local publicans, estates and home brewers. Malt houses are typically long, low buildings, no more than two storeys high, in a vernacular style. The germination of barley is hindered by high temperatures, so many malt houses only operated in the winter. This provided employment for agricultural workers whose labour was not much in demand during the winter months.[3]

During the nineteenth century many small breweries disappeared. Improved techniques allowed larger breweries and specialist maltsters to build their own maltings and operate year-round. These were often housed in multi-storey buildings. It was also more efficient to transport malt than barley to the brewery, so many large breweries set up their own maltings near railways in the barley growing districts of eastern England.[3]

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, pneumatic malting was introduced, in which the barley is aerated and the temperature carefully controlled, accelerating the germination. Large malting floors were no longer necessary, but power consumption was high, so floor malting held on well into the twentieth century.[3] Only a handful of traditional malting floors are still in use.[4]

Notable buildings

[edit]All the following are Grade II* listed buildings, unless otherwise noted.

- Ye Old Corner Cupboard in Winchcombe, Gloucestershire. Formerly a farmhouse, now an inn, 1872, with a 19th-century malthouse along one wing.[5]

- The Malt House in Alton, Staffordshire. House with attached granary, and underground maltkiln and cellars. Late 17th-century. Under the house, a stone barrel vaulted cellar, with inserted floor, 19th-century, forming a maltkiln.[6]

- Great Cliff Malt House in Chevet, West Yorkshire. Early-mid 17th-century. Attached kiln house. The malt house is a single vessel with heavy beams and chamfered purlins supporting a lime-ash floor.[7]

- Warminster Maltings in Wiltshire, 18th-century, rebuilt 1879.[8] Group tours offered.[9]

- Tuckers Maltings in Newton Abbot, Devon, built 1900; Grade II listed.[10] Open to the public for guided tours.[11]

- Great Ryburgh maltings (not a listed building) in Norfolk has been producing malt on traditional malting floors for two centuries. The oldest remaining building was built in the 1890s and has three working floors where a staff of three make about 3,000 tonnes of malt per year. In 2004, modern plant on the site produced some 112,000 tonnes.[4]

- Dereham Maltings (1881, Grade II listed)[12] in Dereham, Norfolk, was converted into flats after production moved to Great Ryburgh.[13]

- Ditherington Flax Mill, a former flax mill in Shrewsbury, Shropshire, was converted to maltings in 1898. Grade I listed for its innovative construction.[14]

- Bass Maltings[15] form an industrial complex in the Lincolnshire market town of Sleaford, disused since 1959. Constructed between 1901 and 1907 to Herbert A. Couchman's design for the Bass brewery, the maltings are the largest complex of their kind in England.

Malt tax

[edit]The malt tax was introduced in Britain in 1697, and was repealed in 1880.[16]

The rate for malted barley was 6d. per bushel in 1697 and had risen to 2s. 7d. in 1834.[1] In 1789 the malt tax raised £ million, 11.5% of all taxes. In 1802 the malt duty rose from 1s. 41⁄4d. a bushel to 2s. 5d., then to 4s. 53⁄4d. in 1804, driven upwards by the need to finance the French Wars of 1793–1815.[17] In 1865 the total revenue was reported to be six million sterling a year.[18]

There were also numerous regulations in place regarding the malting process. The cistern and the couch-frame had to be constructed in a particular manner, to permit the excise officer to gauge the grain. The maltster had to give notice before wetting any grain; 24 hours in the city or market-town, 48 hours elsewhere. The grain had to be kept covered with water for 48 hours, excepting one hour for changing the water. Grain could only be put in the cistern between 8am and 2pm, and taken out between 7am and 4pm. It had to remain in the couch frame for at least 26 hours. Once thrown out of the cistern, it could not be sprinkled for 12 days. A survey book or ledger had to be kept to record the process and the gauging of the grain in the cistern, the couch, and on the floor.[1] The volume of the grain was carefully measured, based upon the mean width, length and height, and calculated by mental arithmetic, pen and paper, or slide rule. The duty to be charged was based upon the largest gauge of either the cistern, couch or floor after a multiplying factor of 1.6 was applied to the larger of the cistern or couch gauges.[19]

See also

[edit]- Oast house – another type of building used in beer manufacture for drying hops, which is topped by a similar cowl structure

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Commissioners of Inquiry into the excise establishment, and into the management and collection of the excise revenue throughout the United Kingdom. Malt. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1835. pp. 1–69.

- ^ a b "How Malt is Made". Great Dunmow Maltings. 2014. Archived from the original on 24 January 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Palmer, Marilyn; Neaverson, Peter (1994). Industry in the Landscape: 1700–1900. Routledge. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-0-415-11206-2.

- ^ a b Pollitt, Michael (24 January 2004). "Norfolk's maltsters to the world" (PDF). Hidden Norfolk. Archived from the original on 3 April 2005. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "Ye Old Corner Cupboard, Winchcombe (1091517)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "The malt house, Alton (1037891)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "Great Cliff Malt house (1135604)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "Pound Street Malthouse (1036240)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Tours of the Maltings". Warminster Maltings. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Tuckers Maltings (1256785)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Tuckers Maltings". Torquay. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "The Maltings (1342708)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Dereham Maltings (Crisp Malting Group) Norwich Road DEREHAM". Norfolk County Council. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ Historic England. "Ditherington Flax Mill (1270576)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Historic England. "Former maltings of Bass Industrial Estate (1062154)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ "Malt Tax". The History Channel. Retrieved 8 March 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Clark, Christine (1998). The British Malting Industry Since 1830. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 24. ISBN 1-85285-170-8.

- ^ "How they Tax Common Luxuries in England". The New York Times. 26 February 1865. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- ^ Nesbit, Anthony; Little, W. (1822). "IV Malt Gauging". A treatise on practical gauging. Longman, Brown, Green & Longmans. pp. 428–448.

Further reading

[edit]- Patrick, Amber (2004). Maltings In England. English Heritage.