Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

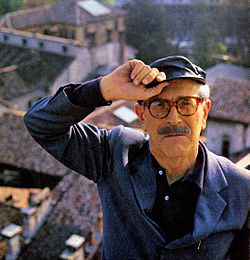

Mario Soldati

View on Wikipedia

Mario Soldati (17 November 1906 – 19 June 1999) was an Italian writer and film director. In 1954, he won the Strega Prize for Lettere da Capri. He directed several works adapted from novels, and worked with leading Italian actresses, such as Alida Valli, Sophia Loren and Gina Lollobrigida.

Key Information

Biography

[edit]A native of Turin, Soldati attended the Liceo Sociale, a Jesuit school, and finished secondary school at age 17. He then studied humanities at the University of Turin. At that time, the university was a hotbed of intellectual activity and the young Soldati met and befriended the likes of activist and writer Carlo Levi and journalist Giacomo Debenedetti, who were his seniors. He later studied History of Art at the University of Rome. He started publishing novels in 1929. He achieved the widest notice with America primo amore, published in 1935, a memoir of the time he spent teaching at Columbia University. He won literary awards for his work, most notably the Strega Prize for Lettere da Capri in 1954.

Also interested in film, Soldati began directing in 1938. His most well-known films are Piccolo mondo antico (1941) and Malombra (1942) with Isa Miranda, both based on novels by Antonio Fogazzaro. These two films belong to the early 1940s movement in Italian cinema known as calligrafismo. Other popular films were Eugenie Grandet, based on Balzac's novel, with Alida Valli; Fuga in Francia (1948); The River Girl (starring Sophia Loren), and La provinciale (starring Gina Lollobrigida). Soldati also regularly published articles in Italian newspapers, including Il Mondo, Il Corriere della Sera, La Stampa, Avanti, L'Unità and Il Giorno.

Soldati died at Lerici in 1999. He was 92.

Legacy and honours

[edit]- 1954, Strega Prize for Lettere da Capri

- 2010, his 1950 film I'm in the Revue was shown as part of a retrospective on Italian comedy at the 67th Venice International Film Festival.[1]

Filmography

[edit]- The Table of the Poor (1932)

- What Scoundrels Men Are! (1932)

- The Opera Singer (1932)

- Steel (1933)

- Giallo (1933)

- The Great Appeal (1936)

- But It's Nothing Serious (1936)

- The Countess of Parma (1936)

- The Woman of Monte Carlo (La signora di Montecarlo) (1938)

- Princess Tarakanova (1938)

- Tonight at Eleven (1938)

- I Want to Live with Letizia (1938)

- The Cuckoo Clock (1938)

- Two Million for a Smile (1939)

- The Document (1939)

- Castles in the Air (1939)

- Dora Nelson (1939)

- A Romantic Adventure (1940)

- Tutto per la donna (1940)

- Saint Rogelia (1940)

- The Sin of Rogelia Sanchez (1940)

- Piccolo mondo antico (1941)

- A Pistol Shot (1942)

- Tragic Night (1942)

- Malombra (1942)

- In High Places (Quartieri alti) (1945)

- His Young Wife (Le miserie del Signor Travet) (1945)

- Daniele Cortis (also known as Elena) (1947)

- Eugenie Grandet (Eugenia Grandet) (1947)

- Flight Into France (Fuga in Francia) (1948)

- Chi è Dio (1948)

- I'm in the Revue (Botta e risposta) (1950)

- Her Favourite Husband (The Taming of Dorothy; Quel bandito sono io) (1950)

- Women and Brigands (1950)

- O.K. Nero (O.K. Nerone) (1951)

- È l'amor che mi rovina (1951)

- Three Corsairs (I tre corsari) (1952)

- Jolanda, the Daughter of the Black Corsair, a.k.a. Yolanda (Jolanda, la figlia del corsaro nero) (1952)

- The Adventures of Mandrin (1952)

- The Dream of Zorro (1952)

- The Wayward Wife (La provinciale) (1953)

- Of Life and Love (Questa è la vita) (1954)

- The Stranger's Hand (1954)

- The River Girl (La donna del fiume) (1955)

- The Virtuous Bigamist (Sous le ciel de Provence) (1956)

- Italia piccola (1957)

- Count Max (1957)

- Policarpo (Policarpo, ufficiale di scrittura) (1959)

Bibliography

[edit]- 24 Hours in a Film Studio (1935 essay; as Franco Pallavera)

References

[edit]- ^ "Italian Comedy - The State of Things". labiennale.org. Archived from the original on 1 August 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

External links

[edit]- Mario Soldati at IMDb

- Mario Soldati mostra virtuale (in Italian)