Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

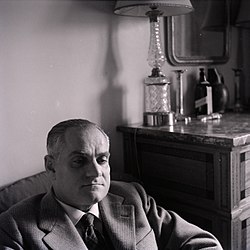

Alberto Moravia

View on Wikipedia

Alberto Pincherle (Italian: [alˈbɛrto ˈpiŋkerle]; 28 November 1907 – 26 September 1990), known by his pseudonym Alberto Moravia (US: /moʊˈrɑːviə, -ˈreɪv-/ moh-RAH-vee-ə, -RAY-;[1][2][3] Italian: [moˈraːvja]), was an Italian novelist and journalist. His novels explored matters of modern sexuality, social alienation and existentialism. Moravia is best known for his debut novel Gli indifferenti (The Time of Indifference 1929) and for the anti-fascist novel Il conformista (The Conformist 1947), the basis for the film The Conformist (1970) directed by Bernardo Bertolucci. Other novels of his adapted for the cinema are Agostino, filmed with the same title by Mauro Bolognini in 1962; Il disprezzo (A Ghost at Noon or Contempt), filmed by Jean-Luc Godard as Le Mépris (Contempt 1963); La noia (Boredom), filmed with that title by Damiano Damiani in 1963 and released in the US as The Empty Canvas in 1964 and La ciociara, filmed by Vittorio De Sica as Two Women (1960). Cédric Kahn's L'Ennui (1998) is another version of La noia.

Key Information

Moravia once remarked that the most important facts of his life had been his illness, a tubercular infection of the bones that confined him to a bed for five years and Fascism because they both caused him to suffer and do things he otherwise would not have done. "It is what we are forced to do that forms our character, not what we do of our own free will."[4] Moravia was an atheist.[5] His writing was marked by its factual, cold, precise style, often depicting the malaise of the bourgeoisie. It was rooted in the tradition of nineteenth-century narrative, underpinned by high social and cultural awareness.[6] Moravia believed that writers must, if they were to represent 'a more absolute and complete reality than reality itself', "assume a moral position, a clearly conceived political, social, and philosophical attitude" but also that, ultimately, "A writer survives in spite of his beliefs".[7] Between 1959 and 1962 Moravia was president of PEN International, the worldwide association of writers.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Alberto Pincherle was born in Via Sgambati in Rome, Italy, to a wealthy middle-class family. His chosen pen name "Moravia" equals to Moravia, which is one of historic Czech lands, and was linked to his paternal grandmother. His Jewish Venetian father, Carlo, was an architect and a painter. His Catholic Anconitan mother, Teresa Iginia de Marsanich, was of Dalmatian origin. His family had interesting twists and developed a complex cultural and political character. The brothers Carlo and Nello Rosselli, founders of the anti-fascist resistance movement Giustizia e Libertà, murdered in France by Benito Mussolini's order in 1937, were paternal cousins and his maternal uncle, Augusto De Marsanich, was an undersecretary in the National Fascist Party cabinet.[8]

Moravia did not finish conventional schooling because, at the age of nine, he contracted tuberculosis of the bone, which confined him to bed for five years. He spent three years at home and two in a sanatorium near Cortina d'Ampezzo, in north-eastern Italy. Moravia was an intelligent boy, and devoted himself to reading books and some of his favourite authors were Giosuè Carducci, Giovanni Boccaccio, Fyodor Dostoevsky, James Joyce, Ludovico Ariosto, Carlo Goldoni, William Shakespeare, Molière, Nikolai Gogol and Stéphane Mallarmé. He learned French and German and wrote poems in French and Italian.

In 1925 at the age of 18, he left the sanatorium and moved to Bressanone. During the next three years, partly in Bressanone and partly in Rome, he began to write his first novel, Gli indifferenti (Time of Indifference), published in 1929. The novel is a realistic analysis of the moral decadence of a middle-class mother and two of her children. In 1927, Moravia met Corrado Alvaro and Massimo Bontempelli and started his career as a journalist with the magazine 900. The journal published his first short stories, including Cortigiana stanca (The Tired Courtesan in French as Lassitude de courtisane, 1927), Delitto al circolo del tennis (Crime at the Tennis Club, 1928), Il ladro curioso (The Curious Thief) and Apparizione (Apparition, both 1929).

Gli indifferenti and Fascist ostracism

[edit]

Gli indifferenti was published at his own expense, costing 5,000 Italian lira. Literary critics described the novel as a noteworthy example of contemporary Italian narrative fiction.[9] The next year, Moravia started collaborating with the newspaper La Stampa, then edited by author Curzio Malaparte. In 1933, together with Mario Pannunzio, he founded the literary review magazines Caratteri (Characters) and Oggi (Today) and started writing for the newspaper Gazzetta del Popolo. The years leading to World War II were difficult for Moravia as an author; the Fascist regime prohibited reviews of Le ambizioni sbagliate (1935), seized his novel La mascherata (Masquerade, 1941) and banned Agostino (Two Adolescents, 1941). In 1935 he travelled to the United States to give a lecture series on Italian literature. L'imbroglio (The Cheat) was published by Bompiani in 1937. To avoid Fascist censorship, Moravia wrote mainly in the surrealist and allegoric styles; among the works is Il sogno del pigro (The Dream of the Lazy). The Fascist seizure of the second edition of La mascherata in 1941, forced him to write under a pseudonym. That same year, he married the novelist Elsa Morante, whom he had met in 1936. They lived in Capri, where he wrote Agostino. After the Armistice of 8 September 1943, Moravia and Morante took refuge in Fondi, on the border of province of Frosinone, a region to which fascism had arbitrarily imposed the name "ciociaria"; the experience inspired La ciociara (1957) (Two Woman, 1958).

Return to Rome and national popularity

[edit]In May 1944, after the liberation of Rome, Alberto Moravia returned. He began collaborating with Corrado Alvaro, writing for important newspapers such as Il Mondo and Il Corriere della Sera, the latter publishing his writing until his death. After the war, his popularity steadily increased, with works such as La Romana (The Woman of Rome, 1947), La Disubbidienza (Disobedience, 1948), L'amore coniugale e altri racconti (Conjugal Love and other stories, 1949) and Il conformista (The Conformist, 1951). In 1952 he won the Premio Strega for I Racconti and his novels began to be translated abroad and La Provinciale was adapted to film by Mario Soldati; in 1954 Luigi Zampa directed La Romana and in 1955 Gianni Franciolini directed I Racconti Romani (The Roman Stories, 1954) a short collection that won the Marzotto Award. In 1953, Moravia founded the literary magazine Nuovi Argomenti (New Arguments), which featured Pier Paolo Pasolini among its editors. In the 1950s, he wrote prefaces to works such as Belli's 100 Sonnets, Brancati's Paolo il Caldo and Stendhal's Roman Walks. From 1957, he also reviewed and criticised cinema for the weekly magazines L'Europeo and L'Espresso. His criticism is collected in the volume Al Cinema (At the Cinema, 1975).

La noia and later life

[edit]In 1960, Moravia published La noia (Boredom or The Empty Canvas), the story of the troubled sexual relationship between a young, rich painter striving to find sense in his life and an easygoing girl in Rome. It became one of his most famous novels, and won the Viareggio Prize. An adaptation was filmed by Damiano Damiani in 1962. Another adaptation of the book is the basis of Cédric Kahn's film L'Ennui (1998). Several films were based on his other novels: in 1960, Vittorio De Sica adapted La ciociara (Two Women), starring Sophia Loren; in 1963, Jean-Luc Godard filmed Il disprezzo (Contempt); and in 1964, Francesco Maselli filmed Gli indifferenti (Time of Indifference). In 1962, Moravia and Elsa Morante parted, despite never divorcing. He went to live with the young writer Dacia Maraini and concentrated on theatre. In 1966, he, Maraini and Enzo Siciliano founded Il porcospino, which staged works by Moravia, Maraini, Carlo Emilio Gadda and others.

In 1967 Moravia visited China, Japan and Korea. In 1971 he published the novel Io e lui (I and He or The Two of Us) about a screenwriter, his independent penis and the situations to which he thrusts them and the essay Poesia e romanzo (Poetry and Novel). In 1972 he went to Africa, which inspired his work A quale tribù appartieni? (Which Tribe Do You Belong To?), published in the same year. His 1982 trip to Japan, including a visit to Hiroshima, inspired a series of articles for L'Espresso magazine about the atomic bomb. The same theme is in the novel L'uomo che guarda (The Man Who Looks, 1985) and the essay L'inverno nucleare (The Nuclear Winter), including interviews with some contemporary principal scientists and politicians.

The short story collection, La Cosa e altri racconti (The Thing and Other Stories), was dedicated to Carmen Llera, his new companion (forty-five years his junior), whom he married in 1986, after Morante's death in November 1985. In 1984, Moravia was elected to the European Parliament as a member of the Italian Communist Party. His experiences at Strasbourg, which ended in 1988, are recounted in Il diario europeo (The European Diary). In 1985 he won the title of European Personality. Moravia was a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, having been nominated 13 times between 1949 and 1965.[10] In September 1990, Alberto Moravia was found dead in the bathroom of his Lungotevere apartment, in Rome. In that year, Bompiani published his autobiography, Vita di Moravia (Life of Moravia).

Themes and literary style

[edit]Moral aridity, the hypocrisy of contemporary life and the inability of people to find happiness in traditional ways such as love and marriage are the regnant themes in the works of Alberto Moravia. Usually, these conditions are pathologically typical of middle-class life; marriage is the target of works such as Disobedience and L'amore coniugale (Conjugal Love, 1947). Alienation is the theme in works such as Il disprezzo (Contempt or A Ghost at Noon, 1954) and La noia (The Empty Canvas) from the 1950s, despite observation from a rational-realistic perspective. Political themes are often present; an example is La Romana (The Woman of Rome, 1947), the story of a prostitute entangled with the Fascist regime and with a network of conspirators. The extreme sexual realism in La noia (The Empty Canvas, 1960) introduced the psychologically experimental works of the 1970s.

Moravia's writing style was highly regarded for being extremely stark and unadorned, characterised by elementary, common words in an elaborate syntax. A complex mood is established by mixing a proposition constituting the description of a single psychological observation mixed with another such proposition. In the later novels, the inner monologue is prominent.

Works

[edit]- Gli indifferenti (1929), novel (The Time of Indifference, trans. Angus Davidson (1953), Tami Calliope (2000))

- Le ambizioni sbagliate (1935), novel (Wheel of Fortune (original) or Mistaken Ambitions (Moravia's preference), trans. Arthur Livingston (1938))

- La bella vita (1935), short stories

- I sogni del pigro (1940), short stories

- La mascherata (1941), novel (The Fancy Dress Party, trans. Angus Davidson (1947))

- La cetonia (1944), short stories

- Agostino (1944), novel (Agostino, trans. Beryl de Zoete (1947), Michael F. Moore (2014); frequently coupled with La disubbidienza as Two Adolescents)

- L'epidemia (1944), short stories

- La romana (1947), novel (The Woman of Rome, trans. Lydia Holland (1949), revised and updated by Tami Calliope (1999))

- La disubbidienza (1948), novel (Luca (U.S.) or Disobedience (UK), trans. Angus Davidson (1950); frequently coupled with Agostino as Two Adolescents)

- L'amore coniugale (1949), novel (Conjugal Love, trans. Angus Davidson (1951), Marina Harss (2007))

- Il conformista (1951), novel (The Conformist, trans. Angus Davidson (1952), Tami Calliope (1999))

- I racconti, 1927–1951 (1952), short stories (first selection, made in consultation with Moravia: Bitter Honeymoon and Other Stories, trans. Frances Frenaye, Baptista Gilliat Smith and Bernard Wall (1954); supplementary selection: The Wayward Wife and Other Stories, trans. Angus Davidson (1960); the two English selections present sixteen of the twenty-four stories in the Italian original)

- Racconti romani (1954), short stories (selection: Roman Tales, trans. Angus Davidson (1954))

- Il disprezzo (1954), novel (A Ghost at Noon (original) or Contempt (to align with the film), trans. Angus Davidson (1954))

- La ciociara (1957), novel (Two Women, trans. Angus Davidson (1958))

- Beatrice Cenci (1958), play (Beatrice Cenci, trans. Angus Davidson (1965))

- Nuovi racconti romani (1959), short stories (selection: More Roman Tales, trans. Angus Davidson (1963))

- La noia (1960), novel (The Empty Canvas (original) or Boredom (reissue), trans. Angus Davidson (1961))

- L'automa (1962), short stories (The Fetish, trans. Angus Davidson (1964))

- L'uomo come fine e altri saggi (1964), essays (Man as an End: A Defense of Humanism: Literary, Social and Political Essays, trans. Bernard Wall (1965))

- L'attenzione (1965), novel (The Lie, trans. Angus Davidson (1966))

- Una cosa è una cosa (1967), short stories (Command, and I Will Obey You, trans. Angus Davidson (1969))

- La rivoluzione culturale in Cina. Ovvero il Convitato di pietra (1967), essay (The Red Book and the Great Wall: An Impression of Mao's China, trans. Ronald Strom (1968))

- Il dio Kurt (1969), play

- La vita è gioco (1969), play

- Il paradiso (1970), short stories (Paradise and Other Stories (UK) or Bought and Sold (U.S.), trans. Angus Davidson (1971))

- Io e lui (1971), novel (The Two of Us (UK) or Two: A Phallic Novel (U.S.), trans. Angus Davidson (1972))

- A quale tribù appartieni (1972), essays (Which Tribe Do You Belong To?, trans. Angus Davidson (1974)), "collection of articles from 10 years' junketing in Africa"[11]

- Un'altra vita (1973), short stories (Lady Godiva and Other Stories (original) or Mother Love (reissue), trans. Angus Davidson (1975))

- Al cinema (1975), essays

- Boh (1976), short stories (The Voice of the Sea and Other Stories, trans. Angus Davidson (1978))

- La vita interiore (1978), novel (Time of Desecration, trans. Angus Davidson (1980))[12]

- Impegno controvoglia (1980), essays

- 1934 (1982), novel (1934, trans. William Weaver (1983))

- La cosa e altri racconti (1983), short stories (Erotic Tales, trans. Tim Parks (1985))

- L'uomo che guarda (1985), novel (The Voyeur, trans. Tim Parks (1986))

- L'inverno nucleare (1986), essays and interviews

- Il viaggio a Roma (1988), novel (Journey to Rome, trans. Tim Parks (1989))

- La villa del venerdì e altri racconti (1990), short stories

Reviews

[edit]- Kelman, James (1980), review of Desecration, in Cencrastus No. 4, Winter 1980–81, p. 49, ISSN 0264-0856

See also

[edit]- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century, a list which includes Contempt or A Ghost at Noon.

References

[edit]- ^ "Moravia, Alberto". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Moravia". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. OCLC 1032680871. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Moravia". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ Accrocca, E.F. Roma allo specchio nella narrativa Italiano da De Amicis al primo Moravia, Istituto Storia Romana, Rome 1958. Reprinted in Giuliano Dego, Moravia (Writers and Critics Series), Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh 1966, page 3, ASIN B0000CN5PF.

- ^ Viola, Carmelo R. (1991). "Alberto Moravia o del "realismo borghese"". Fermenti (in Italian) (203). Rome: Fermenti Editricce. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Dego, Giuliano (1966). Moravia (Writers and Critics Series). Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd. Foreword.

- ^ Burnside, John (8 July 2011). "My hero Alberto Moravia". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Rose, Peter Isaac (2005). The Dispossessed: An Anatomy Of Exile. Amherst & Boston: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 1558494669.

- ^ Moravia, Alberto (1985). L'uomo che guarda. Milan: Bompiani. Foreword by Giorgio Cavallini.

- ^ "Nomination%20archive". April 2020.

- ^ Review by Paul Theroux

- ^ Alter, Robert (1 June 1980). "The Erotic Terrorist; Moravia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 April 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Alberto Moravia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alberto Moravia at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Alberto Moravia at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Alberto Moravia at Wikiquote- The Paris Review Interview

- Petri Liukkonen. "Alberto Moravia". Books and Writers.

- Listen to Pioggia di Maggio by Alberto Moravia free download on mp3

- Listen to Romolo e Remo, one of Moravia's Racconti Romani

- PEN International