Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

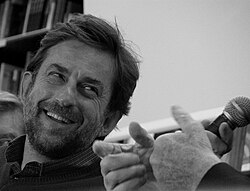

Nanni Moretti

View on Wikipedia

Giovanni "Nanni" Moretti (Italian pronunciation: [ˈnanni moˈretti]; born 19 August 1953) is an Italian film director, producer, screenwriter, and actor.

Key Information

He is most known for his Palme d'Or winner film The Son's Room (2001) and his Special Jury Prize winner film Sweet Dreams (1981). He is also the recipient of three David di Donatello Award for Best Film, for: Caro diario in 1994, The Son's Room in 2001, and The Caiman in 2006.

Every film he directed since Caro diario has been shown at main competition of the Cannes Film Festival. In 2012 he served as the jury president of the festival's main competition.

Early life

[edit]Moretti was born in Bruneck, Italy[1] to Roman parents who were both teachers. His father was the late epigraphist Luigi Moretti, a Greek teacher at Sapienza University of Rome. His brother is literary scholar Franco Moretti.[2][3]

Career

[edit]While growing up Moretti discovered his two passions, the cinema and water polo. Having finished his studies he pursued a career as a producer, and in 1973 directed his first two short films: Pâté de bourgeois and The Defeat (La sconfitta).

In 1976, Nanni Moretti's first feature film Io sono un autarchico (I Am Self-Sufficient) was released. In 1978, he wrote, directed and starred in the movie Ecce Bombo, which tells the story of a student having problems with his entourage. It was screened at the Cannes Festival. Sogni d'oro won the Special Jury Prize at the 38th Venice International Film Festival. La messa è finita won the Silver Bear – Special Jury Prize at the 36th Berlin International Film Festival.[4]

Having played waterpolo in the B division of the Italian championship, his experience later inspired his 1989 film Red Wood Pigeon ("palombella," which literally means "little pigeon," refers to a type of lob shot).

He may be best known for his films Caro diario (1993; followed in 1998 by a sequel, Aprile) and La stanza del figlio (The Son's Room, 2001), the latter of which won the Palme d'Or at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival.[5]

The Caiman (2006) is in part about Berlusconi's controversies: in one of the three portraits of the Italian prime minister Moretti himself plays Berlusconi.[6] His 2011 film We Have a Pope screened In Competition at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, follows the conclave election of new Pope.[7]

His 2015 film Mia Madre was selected to compete for the Palme d'Or at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival, and won the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury.[8] His 2021 and 2023 films Three Floors and A Brighter Tomorrow were also selected to compete for the Palme d'Or at the 2021 and 2023 Cannes Film Festival.

Moretti has used certain actors several times in his films, generally playing minor roles. His father Luigi appears in 6 films, Dario Cantarelli and Mauro Fabretti in 5, Antonio Petrocelli in 4. More notable Italian actors he has employed frequently in his films include Silvio Orlando, who appears in 5 films (including the role of protagonist in Il caimano) and Laura Morante, who was featured in Sogni d'oro, Bianca and The Son's Room. [citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]Even though his works have not been widely seen outside Europe, within his country, Moretti is known as a maker of wryly humorous and eccentric films, usually starring himself.

Moretti says he is not religious. In his own words: "I remember the shirts that said 'Thank God I'm an atheist'. Funny. But I do not think so. I'm not a believer and I'm sorry".[9]

Moretti is also a famous outspoken political leftist in Italian politics. In 2002, he organized street protests against the government of Silvio Berlusconi, besides his own documentary film The Thing (La cosa), which follows the first meeting of Italian leftist militants after the Italian Communist Party's dissolution proposal in 1989.

He lives in Rome, having been resident since birth, where he is co-owner of a small movie theater, Nuovo Sacher, named like this because of Moretti's passion for Sachertorte.[10] The short film, Il Giorno della prima di Close Up (Opening Day of Close-Up, 1996), shows Moretti at his theatre attempting to encourage patrons to attend the opening day of Abbas Kiarostami's film, Close Up.

In April 2025, Moretti was hospitalised after suffering a heart attack.[11]

Filmography

[edit]Feature films

[edit]| Year | English title | Original title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | I Am Self Sufficient | Io sono un autarchico | |

| 1977 | Un autarchico a palazzo | TV movie | |

| 1978 | Ecce bombo | ||

| 1981 | Sweet Dreams | Sogni d'oro | Special Jury Prize at the 38th Venice International Film Festival |

| 1984 | Sweet Body of Bianca | Bianca | |

| 1985 | The Mass Is Ended | La messa è finita | Special Jury Prize at the 36th Berlin International Film Festival |

| 1989 | Red Wood Pigeon | Palombella Rossa | |

| 1993 | Caro diario | Best Director at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival | |

| 1998 | April | Aprile | |

| 2001 | The Son's Room | La stanza del figlio | Palme d'Or winner |

| 2006 | The Caiman | Il caimano | |

| 2011 | We Have a Pope | Habemus Papam | |

| 2015 | Mia Madre | ||

| 2021 | Three Floors | Tre piani | |

| 2023 | A Brighter Tomorrow | Il sol dell'avvenire | |

| TBA | It Will Happen Tonight | Succederà questa notte | Filming[12] |

Short films

[edit]- La sconfitta (1973 short)

- Pâté de bourgeois (1973 short)

- The Only Country In The World (L'unico paese al mondo, 1994 short)

- Opening Day of Close-Up (Il Giorno della prima di Close Up, 1996 short)

- The Last Customer (2002 short)

- Il grido d'angoscia dell'uccello predatore (2003 short)

- L'ultimo campionato (2007 short)

- Diary Of A Moviegoer (Diario di uno spettatore, 2007 short of To Each His Own Cinema)

- Film Quiz (2008 short)

- Scava dolcemente l'addome (2013 short)

- Autobiografia dell'uomo mascherato (2013 short)

- Ischi allegri e clavicole sorridenti (2017 short)

- Piazza Mazzini (2017 short)

Documentaries

[edit]- Come parli frate? (1974 medium)

- The Thing (La cosa, 1990 medium)

- Santiago, Italia (2018 documentary)

Actor only

[edit]- Father and Master (Padre padrone, 1977) – directed by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani

- Riso in bianco: Nanni Moretti atleta di se stesso (TV movie, 1984) – directed by Marco Colli

- It's Happening Tomorrow (Domani accadrà, 1988) – directed by Daniele Luchetti

- The Yes Man (Il portaborse, 1991) – directed by Daniele Luchetti

- The Second Time (La seconda volta, 1995) – directed by Mimmo Calopresti

- I Can See It in Your Eyes (2004) – directed by Valia Santella – cameo

- Quiet Chaos (Caos calmo, 2008) – directed by Antonello Grimaldi

- Venanzio Revolt: i miei primi 80 anno di cinema (2016) – directed by Fabrizio Dividi, Marta Evangelisti, Vincenzo Greco – narrator

- The Hummingbird (2022)

Awards

[edit]- Cannes Film Festival

- Prix de la mise en scène 1994: Caro diario

- Palme d'Or 2001: The Son's Room

- Prix de la FIPRESCI 2001: The Son's Room

- Carrosse d'Or 2004

- Rome's Award 2006: Il caimano

- Ecumenical Prize 2015: Mia madre

- Venice Film Festival

- Silver Lion – Special Jury Prize 1981: Sweet Dreams

- "Bastone Bianco" Filmcritic Award 1989: Red Wood Pigeon

- Berlin International Film Festival

- Silver Bear – Jury Grand Prix 1986: The Mass Is Ended

- Jury C.I.C.A.E Award 1986: The Mass Is Ended

- Chicago International Film Festival

- Golden Plaque for Best Documentary Short Film 2003: The Last Customer

- Silver Plaque for Best Screenplay 2008: Quiet Chaos

- European Film Awards

- FIPRESCI Prize 1994: Caro diario

- São Paulo International Film Festival

- Critics Award 1990: Red Wood Pigeon

- Sudbury Cinéfest

- Best International Film 1994: Caro diario

- Sant Jordi Awards

- Best Foreign Film 1995: Caro diario

- Guild of German Art House Cinemas

- Guild Film Award – Silver 2002: The Son's Room

- David di Donatello

- Alitalia Award 1986

- Golden Medal of the City of Rome 1986

- Best Actor 1991: The Yes Man

- Best Film 1994: Caro diario

- Best Film 2001: The Son's Room

- Best Film 2006: Il caimano

- Best Director 2006: Il caimano

- Best Producer 2006: Il caimano

- Best Documentary 2019: Santiago

- Silver Ribbon

- Best Story 1978: Ecce Bombo

- Best Producer 1988: It's Happening Tomorrow

- Best Story 1990: Red Wood Pigeon

- Best Producer 1992: The Yes Man

- Best Director 1994: Caro diario

- Best Producer 1996: The Second Time

- Best Director 2001: The Son's Room

- Best Producer 2007: Il caimano

- Best Director 2011: We Have a Pope

- Best Story 2011: We Have a Pope

- Best Producer 2011: We Have a Pope

- Ribbon of the Year 2019: Santiago

- Ciak d'oro Awards

- Best Director 1986: The Mass Is Ended

- Best Screenplay 1986: The Mass Is Ended

- Best Director 1990: Red Wood Pigeon

- Best Film 1994: Caro diario

- Best Director 1994: Caro diario

- Best Screenplay 1994: Caro diario

- Best Film 2001: The Son's Room

- Best Director 2001: The Son's Room

- Best Film 2006: Il caimano

- Best Director 2006: Il caimano

- Best Screenplay 2006: Il caimano

- Best Film 2011: We Have a Pope

- Best Screenplay 2011: We Have a Pope

- Best Director 2015: Mia madre

- Honorary Ciak d'oro 2019

- UBU Awards

- Best Italian Movie 1977/78: Ecce Bombo

- Best Actor 1984/85: Sweet Body of Bianca

- Globi d'oro Awards

- Best Debut 1977: I Am Self Sufficient

- Best Film 1994: Caro diario

- Best Film 2011: We Have a Pope

- Cahiers du cinéma

- Best Film 1989: Red Wood Pigeon (ex equo with Do the Right Thing)

- Best Film 1994: Caro diario

- Best Film 2011: We Have a Pope

- Best Film 2015: Mia madre

References

[edit]- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay, ed. (2007). 501 Movie Directors. London: Cassell Illustrated. p. 548. ISBN 9781844035731. OCLC 1347156402.

- ^ Giampiero Mughini, «Moretti, il poeta organizzatore», Corriere della Sera, 21 November 2007

- ^ Valerie Sanders, The Bourgeois: Between History and Literature by Franco Moretti, Times Higher Education, 27 June 2013

- ^ "Berlinale: 1986 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The Son's Room". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Nanni Moretti profile". The Guardian. London, UK. 17 November 2001. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Official Selection". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "2015 Official Selection". Cannes. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ Interview for Style Quanto al suo rapporto con la religione: "Ricordo le magliette con la scritta 'Grazie a Dio sono ateo'. Divertenti. Ma io non la penso così. Non sono credente e mi dispiace"

- ^ "la Repubblica/cinema: Sacher: l'impero di Moretti dedicato a una torta". www.repubblica.it. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Italian director Moretti leaves hospital after heart attack". France 24. 6 April 2025. Retrieved 7 April 2025.

- ^ Roxborough, Scott (17 June 2025). "Nanni Moretti Teaming With Louis Garrel, Jasmine Trinca on New Film". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 4 August 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Chatrian, Carlo & Eugenio Renzi. Conversations avec Nanni Moretti, Paris, 2008, Editions des Cahiers du cinéma.

- Mazierska, Ewa & Laura Rascaroli. The Cinema of Nanni Moretti, Wallflower, 2004.

External links

[edit]- Interview with Nanni Moretti with his own thoughts on his films, filmlinc.com; accessed 12 December 2014.

- Nanni Moretti at IMDb

Nanni Moretti

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Family Background and Childhood

Giovanni Moretti, professionally known as Nanni Moretti, was born on August 19, 1953, in Brunico, a town in the northern Italian province of Bolzano. His parents, both natives of Rome, were intellectuals in the field of classical studies: his father, Luigi Moretti (1922–1991), served as a professor of Greek and epigraphist at Sapienza University of Rome, and his mother, Agata Apicella Moretti, was a teacher of classical languages who continued her career throughout her life until her death in 2010. The family included Moretti's brother, Franco Moretti, a noted literary scholar, and they relocated to Rome soon after his birth, where Moretti was raised in a middle-class household emphasizing education and cultural pursuits.[11][12][13] Moretti's childhood in Rome was marked by early immersion in intellectual and athletic activities. From a young age, he pursued two primary passions—cinema and water polo—frequently attending films in the afternoons before training at local swimming pools in the evenings. These interests reflected the family's scholarly environment while fostering his independent streak; by his teens, Moretti was competing in water polo at an elite level, playing in Italy's top league and as a youth representative for the national team.[14][15][16]Formative Influences and Early Interests

Moretti's parents, both public school teachers originating from Rome, instilled an environment emphasizing education and intellectual pursuits, with his father, Luigi, specializing in classical Greek at the university level.[17] Born on August 19, 1953, in Brunico, South Tyrol—during a family trip—Moretti was raised primarily in Rome, where the absence of familial ties to the arts underscored his independent path toward cinema.[18] Unlike filmmakers recounting childhoods steeped in film, Moretti described his initial draw to movies as an intuitive, somewhat obscure attraction emerging in adolescence, without direct parental encouragement or industry connections.[19] By age 15, around 1968 amid Italy's cultural and political ferment, Moretti began attending cinemas frequently, developing a self-taught appreciation for auteur-driven works of the era, including influences from the French New Wave, though he rejected any notion of a precocious "cinematic childhood."[14] [20] Parallel to this, water polo emerged as his other dominant early passion; he competed at elite levels, joining Italy's top-division clubs and the junior national team, balancing physical discipline with emerging creative inclinations.[21] [22] These interests converged by late high school, when, at 19, Moretti resolved cinema as his primary expressive outlet, prompting him to forgo formal training and produce amateur Super 8 shorts in the early 1970s—works he wrote, directed, and starred in—that circulated successfully among Rome's avant-garde film collectives.[14] [3] This phase reflected a formative tension between personal introspection and collective cultural currents, shaping his later semi-autobiographical style without reliance on institutional pathways.[20]Cinematic Career

Independent Beginnings and Early Works

Nanni Moretti began his filmmaking endeavors in the early 1970s with amateur Super 8 short films that circulated successfully in Roman cinema clubs, establishing his presence in Italy's independent scene.[3] In 1973, at age 20, he directed his first shorts, La sconfitta (The Defeat), which portrayed a young leftist's growing disillusionment during worker and student demonstrations, and Pâté de bourgeois.[23][2] These early experiments highlighted Moretti's satirical lens on political activism and personal alienation, shot with minimal resources as a self-taught filmmaker.[1] His transition to features came with Io sono un autarchico (I Am Self Sufficient) in 1976, a low-budget comedy produced independently and initially filmed on Super 8 before enlargement to 35mm for distribution.[24] The film centers on Michele Apicella—a recurring semi-autobiographical character played by Moretti—as he grapples with failed theatrical ambitions, family tensions, and everyday absurdities in Rome, blending farce with critiques of bourgeois self-sufficiency and avant-garde pretensions.[25][26] Running 94 minutes, it captured the malaise of post-1968 Italian youth while showcasing Moretti's distinctive, improvisational style rooted in direct address and non-professional casts.[27] Building on this foundation, Ecce Bombo (1978) marked Moretti's sophomore feature, shot on 16mm and released in 35mm, achieving cult status as his first nationwide hit with over 1 million admissions in Italy.[28] The 105-minute film employs a fragmented, vignette-based structure to depict the aimless routines and ideological hangovers of former 1960s militants now adrift in the late 1970s, satirizing leftist complacency through scenes of futile meetings, romantic entanglements, and existential rants.[29] Moretti again starred as Michele Apicella, reinforcing his auteur persona amid collective disorientation.[30] These works solidified Moretti's role as a pioneer of Italy's independent cinema, prioritizing personal vision over commercial constraints and influencing a generation of filmmakers with their blend of autobiography, politics, and humor.[31]Breakthrough and Signature Films

Moretti's breakthrough arrived with Ecce Bombo (1978), his second feature film after Io sono un autarchico, which marked his transition from Super 8 shorts to wider recognition.[32] The film, budgeted at 180 million Italian lire (approximately $90,000 at the time), earned over 2 billion lire (about $1 million), achieving substantial commercial success in Italy despite its low-budget origins shot initially in 16mm before release in 35mm.[28] Starring Moretti as Michele Apicella, a recurring alter ego, it satirized the ideological apathy and interpersonal absurdities among young Romans in the wake of the 1968 protests, blending documentary-style realism with comedic vignettes of failed political meetings and personal ennui.[30] Selected for the 1978 Cannes Film Festival, Ecce Bombo established Moretti's reputation for introspective, semi-autobiographical critique of leftist subcultures, influencing his subsequent oeuvre.[32] Among his signature works, Palombella rossa (1989) exemplifies Moretti's fusion of sports, politics, and personal confession. In the film, Moretti reprises Apicella as a communist politician suffering amnesia during a water polo match, using the aquatic chaos as a metaphor for Italy's crumbling ideological certainties on the eve of the Tangentopoli scandals.[10] The narrative interweaves match play with interrogations of party loyalty and memory loss, reflecting Moretti's own disillusionment with the Italian Communist Party's decline.[33] Caro diario (1993) further solidified Moretti's international profile with its tripartite structure blending travelogue, mystery, and illness narrative, all narrated in his distinctive voiceover. The film's episodic form—scooter rides through Rome, a quest for a Rashomon-like truth in Tusculum, and reflections on cancer treatment—earned Moretti the Best Director award at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival.[34] It also secured the Nastro d'Argento for Best Director and Best Producer, highlighting its critical acclaim for innovative hybridity between fiction and autobiography.[35] Moretti's most acclaimed signature film, La stanza del figlio (The Son's Room, 2001), shifted toward dramatic intensity, depicting a bourgeois family's unraveling after their teenage son's scuba diving accident. Premiering at Cannes, it won the Palme d'Or, the festival's top prize, on May 20, 2001, marking the first Italian victory since 1978.[6] Co-written with Linda Ferri and Heidrun Schleef, the film explores grief's psychological toll on Moretti's psychoanalyst protagonist—again a semi-autobiographical stand-in—without his typical irony, prioritizing raw emotional realism over satire.[36]Thematic Evolution and Later Directorial Projects

In his later directorial works, Nanni Moretti shifted emphasis from the overt political satire and autobiographical irony of his formative films toward introspective explorations of personal bereavement, familial disintegration, and the psychological burdens of authority, while retaining confessional undertones that coalesce daily life with broader human frailties.[37][4] This evolution reflects a maturation from generational malaise and leftist self-critique—evident in earlier efforts like Palombella rossa (1989)—to universal motifs of loss and moral accountability, often infused with restrained humor amid tragedy.[38] Such themes underscore a causal realism in depicting how private crises ripple into social disconnection, prioritizing empirical emotional authenticity over ideological preaching. Habemus Papam (2011), premiered at the Venice Film Festival on September 21, 2011, centers on a newly elected pope (Michel Piccoli) who experiences a debilitating panic attack and withdraws from his role, prompting institutional chaos managed by a psychoanalyst played by Moretti himself. The film satirizes Vatican rigidity and clerical detachment while probing deeper into crises of vocation, the clash between personal vulnerability and performative power, and masculinity's constraints within religious hierarchies, contrasting sharply with triumphalist narratives of leadership.[39][40] Critics noted its antithesis to films glorifying institutional resilience, emphasizing instead individual frailty as a barrier to fulfillment.[41] Santiago, Italia (2018), Moretti's first documentary feature, recounts the Italian embassy's sheltering of over 800 Chilean opponents of Augusto Pinochet's regime following the September 11, 1973, coup against Salvador Allende, drawing on survivor interviews and archival footage to highlight diplomatic improvisation and humanitarian resolve amid junta terror. Released December 12, 2018, it frames these events as a testament to cross-national solidarity, with Italian ambassador Giorgio La Pira's legacy enabling refuge that saved lives from torture and disappearance, though Moretti maintains a straightforward, non-sensationalist lens focused on eyewitness veracity rather than dramatic reconstruction.[42][43] Mia Madre (2015), awarded the Cannes Film Festival's Grand Prix on May 24, 2015, follows a filmmaker (Margherita Buy) navigating her mother's terminal illness, a contentious labor dispute on her movie set, and romantic entanglements, blending semi-autobiographical elements with reflections on inadequacy in reconciling professional ambition and filial duty. The narrative interweaves grief's disorientation with comedic vignettes of human error, evolving Moretti's style toward quiet universality in portraying bereavement's isolating causality, where unresolved personal histories exacerbate relational fractures.[44][38] Tre piani (2021), adapted from Eshkol Nevo's 2017 novel and competing at Cannes on July 13, 2021, unfolds across three interconnected vignettes in a Roman apartment building, spanning decades to trace middle-class families' unraveling through parental negligence, judicial miscarriages, and suppressed traumas. Moretti dissects the illusions of bourgeois civility, illustrating how unchecked impulses—such as a father's vengeful denial or a wife's illicit affair—propagate intergenerational harm, with the titular floors symbolizing stratified yet interdependent moral failures.[45][46] In Il sol dell'avvenire (A Brighter Tomorrow, 2023), premiered May 20, 2023, Moretti portrays Giovanni (himself), a director stalled on a film about 1970s terrorism while confronting divorce, a younger lover, and clashes with streaming platforms' constraints, weaving midlife stasis with ironic nods to fading leftist utopias evoked by the title's Soviet origins. The work critiques cinema's commodification versus artistic autonomy, positing renewal through personal reinvention amid ideological disillusionment, though its hopeful irony underscores persistent melancholic denial.[20][9]Recent Developments and Productions

In 2021, Moretti directed Three Floors (Tre piani), an adaptation of Israeli author Eshkol Nevo's novel exploring the interconnected lives of three families in a Rome apartment building over two decades, which competed for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The film received mixed reviews for its ensemble cast performances but was critiqued for uneven pacing in translating the source material's introspective style to screen. Moretti's next directorial effort, A Brighter Tomorrow (Il sol dell'avvenire), released in 2023, featured him as Giovanni, a middle-aged filmmaker grappling with a faltering marriage, professional stagnation, and ideological disillusionment while directing a period piece on the Italian Communist Party. Premiering in competition at Cannes, the semi-autobiographical comedy-drama earned praise for its meta-commentary on cinema's evolving cultural role amid streaming dominance and generational shifts, though some noted its nostalgic tone bordered on self-indulgent.[47] In interviews, Moretti described the project as a "declaration of love" for film's enduring vitality despite personal and industry crises.[19] On April 3, 2025, Moretti was admitted to intensive care in a Rome hospital following a heart attack, as reported by Italian media, marking a significant health setback at age 71.[48] Recovering from this episode, he announced in June 2025 his forthcoming directorial project, It Will Happen Tonight (Succederà Questa Notte), a romantic drama loosely adapted from Nevo's short story collection Hungry Heart, starring Louis Garrel and Jasmine Trinca, with principal photography slated to begin imminently across Rome, Turin, and San Sebastián.[49][50] The film is produced by Moretti's Sacher Film alongside international partners including France's Playtime and Pan-Européenne.[51] In parallel, Moretti has expanded his producing role through Sacher Film, co-producing Primo Viaggio—a drama directed by Alessandro Cassigoli and Casey Kauffman—announced in August 2025 with backing from Rai Cinema and distribution by Teodora Film.[52] This follows his involvement in other recent titles like the 2024 release Vittoria, underscoring a shift toward nurturing emerging Italian talents while maintaining selective directorial output.[52]Political Engagement

Activism Against Center-Right Governments

Moretti played a leading role in the Girotondi citizens' movement, which emerged in early 2002 to protest perceived abuses of power by Silvio Berlusconi's center-right government, including conflicts of interest arising from his media ownership and proposed judicial reforms aimed at shielding him from corruption trials.[53] The movement organized symbolic "circling" demonstrations outside key institutions like courthouses to defend judicial independence and constitutional norms, drawing tens of thousands in events across Italy.[54] On July 31, 2002, Moretti led a protest in Rome against a government-backed justice bill, which opponents viewed as tailored to immunize Berlusconi from legal proceedings; he urged demonstrators to prioritize safeguarding the rule of law over partisan loyalty.[55] In April of that year, he publicly appealed to President Carlo Azeglio Ciampi to intervene and protect state broadcaster RAI from Berlusconi's threats to dismiss executives critical of his policies, arguing that such moves threatened media pluralism.[56] Moretti addressed a crowd exceeding 100,000 at a September 14, 2002, rally in Piazza San Giovanni, Rome, declaring that Italians had "voted for Berlusconi to follow a dream but instead awoke to a nightmare" of power consolidation and legislative favoritism.[57] [58] He continued his public opposition into 2009, participating in the "No Berlusconi Day" demonstrations on December 5, where he specifically condemned the prime minister's dominance over Italy's television landscape, which controlled about 90% of national broadcasting through his private networks and influence over public ones.[59] In August 2023, Moretti denounced legislative proposals by Giorgia Meloni's government to restructure the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia, Italy's leading state film school, as an overreach that undermined artistic autonomy, joining other filmmakers in signing an open letter against the reforms.[60]Internal Critiques of Leftist Movements

In his 1989 film Palombella rossa, Moretti portrayed a communist politician grappling with ideological amnesia during a water polo match, using the narrative to satirize the Italian Communist Party's (PCI) dogmatic rhetoric and failure to adapt post-Berlin Wall, culminating in the protagonist's exasperated declaration, "Le parole sono importanti" (Words are important), which underscores critiques of leftist movements' reliance on outdated, ineffective language that alienates broader audiences.[61][62] This theme recurred in Moretti's real-life interventions, particularly after the center-left coalition's defeat in the April 2001 Italian general election, where the PCI's successor, the Democrats of the Left (DS), under Romano Prodi, secured only 16.6% of the vote despite anti-Berlusconi mobilization.[63] On February 2, 2002, at a DS rally in Rome's Piazza Navona attended by over 200,000 people, Moretti seized the microphone to denounce party leaders, including Prodi and DS secretary Piero Fassino, for their "tepid" and uninspiring discourse, stating, "We were waiting for words that would set us on fire... With these words, you'll never win," and accusing them of losing touch with ordinary citizens' frustrations amid economic stagnation and Berlusconi's media dominance.[64][65] Moretti's outburst, which dominated Italian headlines and prompted Fassino to concede internal communication failures, highlighted broader disillusionment with the PDS/DS's centrist pivot since the PCI's 1991 dissolution, a shift Moretti viewed as diluting principled opposition to neoliberal policies and eroding grassroots mobilization, as evidenced by the left's fragmented 2001 coalition that included marginal gains for Rifondazione Comunista (8.2%) but overall electoral underperformance.[65][66] His critiques extended to the left's intellectual insularity, arguing in subsequent reflections that movements like the DS prioritized elite consensus over confrontational strategies needed to challenge entrenched power, a stance echoed in his support for more radical voices before withdrawing from overt party alignment.[62][67] Later works, such as the 2023 film Il sol dell'Avvenire, revisited 1970s leftist nostalgia through a director's lens, incorporating gags that lampoon the era's ideological excesses and the PCI's rigid structures, reflecting Moretti's ongoing skepticism toward romanticized communism amid the left's post-2008 electoral irrelevance, where parties tracing PCI lineage polled below 20% combined in subsequent cycles.[68] This internal reckoning positioned Moretti as a gadfly within Italian leftism, prioritizing pragmatic renewal over ideological purity, though he has cautioned against sources overstating his apostasy given his consistent anti-right activism.[19]Use of Cinema for Political Satire

Nanni Moretti has utilized cinema to deliver pointed political satire, often through absurd comedy that exposes flaws in Italian ideological landscapes and power structures. His approach integrates personal introspection with broader societal critique, employing antic humor to probe deeper than straightforward polemics, as seen in films that allegorize political disarray via everyday or fantastical scenarios.[10] This method allows Moretti to target inconsistencies within leftist circles while also confronting center-right figures, prioritizing emotional authenticity over dogmatic rhetoric.[10] In Ecce Bombo (1978), Moretti's second feature, he satirizes the post-1968 generation of leftist youth, depicting their political assemblies and personal lives as marked by inertia, self-absorption, and futile idealism amid Rome's urban backdrop.[69] The film's sketch-like structure highlights characters' anxieties and romantic entanglements intertwined with hollow activism, critiquing the gap between revolutionary aspirations and lived disillusionment.[30] This early work established Moretti's signature blend of comedy and political reflection, drawing from his own experiences in Italy's extra-parliamentary left movements.[62] Palombella rossa (1989) extends this satire to the Italian Communist Party (PCI), framing debates through water-polo matches where Moretti plays Michele Apicella, an amnesiac politician grappling with ideological memory loss.[70] The film's slapstick elements, including aquatic confrontations symbolizing factional strife, mock the PCI's rigidity and failure to evolve, presciently anticipating its dissolution and the rise of figures like Silvio Berlusconi.[71] Critics have praised its inventive humor for dissecting capitalism's encroachment and leftist complacency, using pop culture references to underscore generational shifts.[72] Moretti's Il caimano (2006), premiered at the Cannes Film Festival, offers a meta-satirical take on Berlusconi, centering on producer Bruno Belmonte who reluctantly backs a low-budget film about a corrupt media mogul resembling the politician.[73] Incorporating actual footage of Berlusconi's parliamentary antics, the narrative critiques media control and ethical decay in Italian politics, with a Polish character's quip—"Just when we think you have sunk to the bottom—that's when you start digging"—encapsulating public frustration.[73] Though faulted for indirectness in fully dismantling its target, the film underscores Moretti's preference for layered comedy over overt confrontation, blending Bruno's domestic chaos with political allegory.[73][74]