Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Milorg

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2009) |

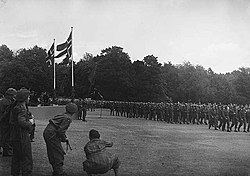

Milorg (abbreviation of militær organisasjon – military organization) was the main Norwegian resistance movement during World War II. Resistance work included intelligence gathering, sabotage, supply-missions, raids, espionage, transport of goods imported to the country, release of Norwegian prisoners and escort for citizens fleeing the border to neutral Sweden.[1]

History

[edit]

Following the German occupation of Norway in April 1940, Milorg was formed in May 1941 as a way of organizing the various groups that wanted to participate in an internal military resistance. At first, Milorg was not well coordinated with the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the British organization to plan and lead resistance in occupied countries. In November 1941 the Milorg became integrated with the High Command of the Norwegian government in exile in London, answering to the British Army's Department British Field Office IV, which dealt with sabotage operations, but Milorg's British counterpart, SOE, was still operating independently. This lack of coordination led to a number of deadly incidents, creating bitterness within Milorg. SOE changed its policy at the end of 1942, and from then on Milorg and SOE efforts were coordinated.[2] Mainly for fear of retaliation, like the Telavåg tragedy in 1942, Milorg kept a low profile at first. But they became more active as the war progressed. Its first permanent bases were established in the summer of 1944. At the time of the German capitulation on 8 May 1945, Milorg had been able to train and supply 40,000 soldiers. They then also played an important part in stabilizing the country.[3][4]

Two-way radio stations

[edit]Twenty of the around 80 radio stations were uncovered, leading to the deaths of at least 20 radio operators in combat or prison. The radio station in the loft of Kvinneklinikken, was raided on 1 April 1944. Knut Haugland shot four of the raiders, and escaped. "Corncrake" (at Flaskebekk) transmitted from 2 April and it was raided on 4 July. Deaths included one German and two Norwegians on site, and one Norwegian at the hospital. The radio stations contributed to Milorg getting a key role in the Nazi home management program (Hjemmefrontens Ledelse), because the majority of HL's communications abroad, went through Milorg's radio network.[5]

Organisation

[edit]Milorg was organised as a council and 14 districts.

- Rådet ("The Council") had between 2–4 members.[6] (In practice, The council ceased to exist from January 1945, when it only consisted of Sven Arntzen and Hauge—both of them being representatives in the leadership of Hjemmefronten (HL), as Milorg's and Krigspolitiet's representatives, respectively.[6])

- Den sentrale ledelse (SL)—"the central leadership"—was subordinate to The council.

Military Committee

[edit]The Military Committee (Militærkommiteen) was subordinate to The council.[7]

Districts

[edit]It counted around 20,000 people by the summer of 1942.[citation needed]

Sub-organizations

[edit]There were export organisations[9] (for transporting fugitive members, to another nation). SL had one, codenamed "Edderkoppen" (The Spider).[9]

Members

[edit]- Lorentz Brinch

- Arne Laudal

- Knut Møyen

- Terje Rollem

- Reidun Røed

- Hjalmar Steenstrup

- Andreas Tømmerbakke

- Herman Watzinger

- Eva Kløvstad District Chief of D-25, who worked under codename Jakob

- Elsa Endresen (codenamed Lotte)[10] (In the last year of the war, Hauge told colleagues in SL, on occasion that "This is so dangerous, that only Lotte can do it!")[10]

- Josef Haraldsen, District Chief of Vestfold, who for years after the war, served as a private in the Home Guard[11]

"The Council"'s leaders

[edit]- Council position "R1": Ole Berg, replaced by Olaf Helset, replaced by Arnold Rørholt (May 1943 – January 1945; no replacement)[6]

- Council spot "R2": Johan Holst, Johan Gørrisen, Sven Arntzen[6]

- "R3": Jacob Schive, Carl Semb, Harald Lohne, Jens Christian Hauge[6]

- "R4: Johan Beichman, Ola Brandstorp (Feb.42 – Dec. 43; no replacement)[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ole Kristian Grimnes. "Norge under andre verdenskrig". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Magne Skodvin. "Milorg". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Thor Ingvart Karlsen. "Tælavåg". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ "Milorg – Hjemmestyrkene – Gutta På Skauen". Universitetet i Bergen Historisk institutt. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Ivar Kraglund. "Knut M Haugland -Offiser, Motstandsmann". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Njølstad p.125

- ^ Njølstad p.155

- ^ Njølstad p.121

- ^ a b Njølstad p.148

- ^ a b Njølstad p.156

- ^ Njølstad p.304

Other sources

[edit]- Andenaes, Johs. (1966) Norway and the Second World War (Arthur Vanous Co) ISBN 978-8251817776

- Riste, Olav, and Berit Nøkleby (1970) Norway 1940-45: the resistance movement (Oslo: Tanum)

- Skodvin, Magne (1991) Norsk historie 1939–1945: krig og okkupasjon (Oslo: Samlaget) ISBN 82-521-3491-2

- Stephenson, Jill; John Gilmour (2013) Hitler's Scandinavian Legacy (A&C Black) ISBN 9781472504975

- Vigness, Paul Gerhardt. (1970) The German Occupation of Norway (Vantage Press)