Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bergen

View on Wikipedia

Bergen (Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈbæ̀rɡən] ⓘ, locally [ˈbæ̂ʁgæn]) is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway after the capital Oslo.

Key Information

In May 2025, the population was 294,029, according to Statistics Norway.[4] The municipality covers 465 square kilometres (180 sq mi) and is on the peninsula of Bergenshalvøyen. The city centre and northern neighbourhoods are on Byfjorden, 'the city fjord'. The city is surrounded by mountains, causing Bergen to be called the "city of seven mountains". Many of the extra-municipal suburbs are on islands. Bergen is the administrative centre of Vestland county. The city consists of eight boroughs: Arna, Bergenhus, Fana, Fyllingsdalen, Laksevåg, Ytrebygda, Årstad, and Åsane.

Trading in Bergen may have started as early as the 1020s. According to tradition, the city was founded in 1070 by King Olav Kyrre and was named Bjørgvin, 'the green meadow among the mountains'. It served as Norway's capital in the 13th century, and from the end of the 13th century became a bureau city of the Hanseatic League. Until 1789, Bergen enjoyed exclusive rights to mediate trade between Northern Norway and abroad, and it was the largest city in Norway until the 1830s when it was overtaken by the capital, Christiania (now known as Oslo). What remains of the quays, Bryggen, is a World Heritage Site. The city was hit by numerous fires over the years. The Bergen School of Meteorology was developed at the Geophysical Institute starting in 1917, the Norwegian School of Economics was founded in 1936, and the University of Bergen in 1946. From 1831 to 1972, Bergen was its own county. In 1972 the municipality absorbed four surrounding municipalities and became a part of Hordaland county.

The city is an international centre for aquaculture, shipping, the offshore petroleum industry and subsea technology, and a national centre for higher education, media, tourism and finance. Bergen Port is Norway's busiest in terms of both freight and passengers, with over 300 cruise ship calls a year bringing nearly half a million passengers to Bergen,[5] a number that has doubled in 10 years.[6] Almost half of the passengers are German or British.[6] The city's main football team is SK Brann and a unique tradition of the city is the buekorps, which are traditional marching neighbourhood youth organisations. Natives speak a distinct dialect, known as Bergensk. The city features Bergen Airport, Flesland and Bergen Light Rail, and is the terminus of the Bergen Line. Four large bridges connect Bergen to its suburban municipalities.

Bergen has a mild winter climate, though with significant precipitation. From December to March, Bergen can, in rare cases, be up to 20 °C (36 °F) warmer than Oslo, even though both cities are at about 60° North. In summer however, Bergen is several degrees cooler than Oslo due to the same maritime effects. The Gulf Stream keeps the sea relatively warm, considering the latitude, and the mountains protect the city from cold winds from the north, north-east and east.

History

[edit]

The city of Bergen was traditionally thought to have been founded by king Olav Kyrre, son of Harald Hardråde in 1070 AD,[8] four years after the Viking Age in England ended with the Battle of Stamford Bridge. Modern research has, however, discovered that a trading settlement had already been established in the 1020s or 1030s.[9]

Bergen gradually assumed the function of capital of Norway in the early 13th century, as the first city where a rudimentary central administration was established. The city's cathedral was the site of the first royal coronation in Norway in the 1150s, and continued to host royal coronations throughout the 13th century. Bergenhus fortress dates from the 1240s and guards the entrance to the harbour in Bergen. The functions of the capital city were lost to Oslo during the reign of King Haakon V (1299–1319).

During the 14th century, North German merchants, who had already been present in substantial numbers since the 13th century, founded one of the four Kontore of the Hanseatic League at Bryggen in Bergen. The principal export traded from Bergen was dried cod from the northern Norwegian coast,[10] which started c. 1100. The city was granted a monopoly for trade from the north of Norway by King Håkon Håkonsson (1217–1263).[11] Stockfish was the main reason that the city became one of North Europe's largest centres for trade.[11] By the late 14th century, Bergen had established itself as the centre of the trade in Norway.[12] The Hanseatic merchants lived in their own separate quarter of the town, where Middle Low German was used, enjoying exclusive rights to trade with the northern fishermen who each summer sailed to Bergen.[13] The Hansa community resented Scottish merchants who settled in Bergen, and on 9 November 1523 several Scottish households were targeted by German residents.[14] Today, Bergen's old quayside, Bryggen, is on UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites.[15]

In 1349, the Black Death was brought to Norway by an English ship arriving in Bergen.[16] Later outbreaks occurred in 1618, 1629 and 1637, on each occasion taking about 3,000 lives.[17] In the 15th century, the city was attacked several times by the Victual Brothers,[18] and in 1429 they succeeded in burning the royal castle and much of the city. In 1665, the city's harbour was the site of the Battle of Vågen, when an English naval flotilla attacked a Dutch merchant and treasure fleet supported by the city's garrison. Accidental fires sometimes got out of control, and one in 1702 reduced most of the town to ashes.[19]

Throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, Bergen remained one of the largest cities in Scandinavia, and it was Norway's biggest city until the 1830s,[20] being overtaken by the capital city of Oslo. From around 1600, the Hanseatic dominance of the city's trade gradually declined in favour of Norwegian merchants (often of Hanseatic ancestry), and in the 1750s, the Kontor, or major trading post of the Hanseatic League, finally closed. During the 17th and 18th centuries, Bergen was involved in the Atlantic slave trade. Bergen-based slave trader Jørgen Thormøhlen, the largest shipowner in Norway, was the main owner of the slave ship Cornelia, which made two slave-trading voyages in 1673 and 1674 respectively; he also developed the city's industrial sector, particularly in the neighbourhood of Møhlenpris, which is named after him.[21] Bergen retained its monopoly of trade with northern Norway until 1789.[22] The Bergen stock exchange, the Bergen børs, was established in 1813.

Modern history

[edit]

Bergen was separated from Hordaland as a county of its own in 1831.[23] It was established as a municipality on 1 January 1838 (see formannskapsdistrikt). The rural municipality of Bergen landdistrikt was merged with Bergen on 1 January 1877. The rural municipality of Årstad was merged with Bergen on 1 July 1915.[24]

During World War II, Bergen was occupied on the first day of the German invasion on 9 April 1940, after a brief fight between German ships and the Norwegian coastal artillery. The Norwegian resistance movement groups in Bergen were Saborg, Milorg, "Theta-gruppen", Sivorg, Stein-organisasjonen and the Communist Party.[25] On 20 April 1944, during the German occupation, the Dutch cargo ship Voorbode anchored off the Bergenhus Fortress, loaded with over 120 tons of explosives, and blew up, killing at least 150 people and damaging historic buildings. The city was subject to some Allied bombing raids, aimed at German naval installations in the harbour. Some of these caused Norwegian civilian casualties numbering about 100.

Bergen is also well known in Norway for the Isdal Woman (Norwegian: Isdalskvinnen), an unidentified person who was found dead at Isdalen ("Ice Valley") on 29 November 1970.[26] The unsolved case encouraged international speculation over the years and it remains one of the most profound mysteries in recent Norwegian history.[27][28]

The rural municipalities of Arna, Fana, Laksevåg, and Åsane were merged with Bergen on 1 January 1972. The city lost its status as a separate county on the same date,[29] and Bergen is now a municipality, in the county of Vestland.

Fires

[edit]The city's history is marked by numerous great fires. In 1198, the Bagler faction set fire to the city in connection with a battle against the Birkebeiner faction during the civil war. In 1248, Holmen and Sverresborg burned, and 11 churches were destroyed. In 1413 another fire struck the city, and 14 churches were destroyed. In 1428 the city was plundered by the Victual Brothers, and in 1455, Hanseatic merchants were responsible for burning down Munkeliv Abbey. In 1476, Bryggen burned down in a fire started by a drunk trader. In 1582, another fire hit the city centre and Strandsiden. In 1675, 105 buildings burned down in Øvregaten. In 1686 another great fire hit Strandsiden, destroying 231 city blocks and 218 boathouses. The greatest fire in history was in 1702, when 90% of the city was burned to ashes. In 1751, there was a great fire at Vågsbunnen. In 1756, yet another fire at Strandsiden burned down 1,500 buildings, and further great fires hit Strandsiden in 1771 and 1901. In 1916, 300 buildings burned down in the city centre including the Swan pharmacy, the oldest pharmacy in Norway, and in 1955 parts of Bryggen burned down.

Toponymy

[edit]Bergen is pronounced in English /ˈbɜːrɡən/ or /ˈbɛərɡən/ and in Norwegian [ˈbæ̀rɡn̩] ⓘ (in the local dialect [ˈbæ̂ʁɡɛn]). The Old Norse forms of the name were Bergvin [ˈberɡˌwin] and Bjǫrgvin [ˈbjɔrɡˌwin] (and in Icelandic and Faroese the city is still called Björgvin). The first element is berg (n.) or bjǫrg (n.), which translates as 'mountain(s)'. The last element is vin (f.), which means a new settlement where there used to be a pasture or meadow.[30] Bergen is often called "the city among the seven mountains". The playwright Ludvig Holberg, inspired by the seven hills of Rome, decided that his home town must be blessed with a corresponding seven mountains, though locals debate which seven they are.

In 1918, there was a campaign to reintroduce the Norse form Bjørgvin as the name of the city. This was turned down – but as a compromise, the name of the diocese was changed to Bjørgvin bispedømme.[31]

Geography

[edit]

Bergen occupies most of the peninsula of Bergenshalvøyen in the district of Midthordland in mid-western Hordaland. The municipality covers an area of 465 square kilometres (180 square miles). Most of the urban area is on or close to a fjord or bay, although the urban area has several mountains. The city centre is surrounded by the Seven Mountains, although there is disagreement as to which of the nine mountains constitute these. Ulriken, Fløyen, Løvstakken and Damsgårdsfjellet are always included as well as three of Lyderhorn, Sandviksfjellet, Blåmanen, Rundemanen and Kolbeinsvarden.[32] Gullfjellet is Bergen's highest mountain, at 987 metres (3,238 ft) above mean sea level.[33] Bergen is far enough north that during clear nights at the solstice, there is borderline civil daylight in spite of the sun having set.[34]

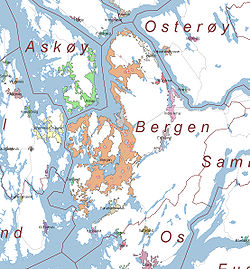

Bergen is sheltered from the North Sea by the islands Askøy, Holsnøy (the municipality of Meland) and Sotra (the municipalities of Fjell and Sund). Bergen borders the municipalities Alver and Osterøy to the north, Vaksdal and Samnanger to the east, Os (Bjørnafjorden) and Austevoll to the south, and Øygarden and Askøy to the west.

Climate

[edit]

Bergen has a temperate oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb, Trewartha: Dolk), with mild summers and cool winters. Rainfall is plentiful in all seasons, along with intermittent snowfall during winter, which often melts quickly. The exceptionally plentiful precipitation that defines the city is caused by orographic lift, sometimes causing more than two months of consecutive rainy days.[35] The city is therefore considered the rainiest city in Europe, although it is not the wettest "place" on the continent.[36][37]

Bergen's weather is much warmer than the city's latitude (60.4° N) might suggest. Temperatures below −10 °C (14 °F) are rare. Summer temperatures sometimes reach the upper 20s, although temperatures over 30 °C were previously only seen a few days each decade. The growing season in Bergen is exceptionally long for its latitude, more than 200 days. Its mild winters and proximity to the Gulf Stream provide the city with a plant hardiness zone of 8b and 9a depending on location; this zone is much more common below 50°N even in Europe, with cities as far south as Bordeaux, Thessaloniki and Istanbul falling into this category. The average date for the last overnight freeze (low below 0 °C (32.0 °F)) in spring is April 4[38] and average date for first freeze in autumn is November 7[39] giving a frost-free season of 216 days.

Extreme temperatures are also quite rare in the city. The highest temperature ever recorded was 33.4 °C (92.1 °F) on 26 July 2019,[40] beating the previous record from 2018 at 32.6 °C (90.7 °F) degrees, and the lowest was −16.3 °C (2.7 °F) in January 1987.[41]

The city is quite cloudy year round, although old sunshine hours data might have caused an underestimate of sunshine hours, due to the city's mountainside location.[42] A new sun recorder was established at Bergen Airport, Flesland (a location with less terrain obscuring the sun) in December 2015, and this recorded an average of 1,596 hours of sun annually during 2016–2022.[43]

| Climate data for Bergen - Florida 1991-2020 normals (12 m, extremes 1957–present, sunshine 2016–2024 (Bergen Airport, Flesland)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.2 (61.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

25.5 (77.9) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

33.4 (92.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

33.4 (92.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

18 (64) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22 (72) |

17.5 (63.5) |

13 (55) |

10.4 (50.7) |

27.2 (81.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15 (59) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.3 (41.5) |

11.7 (53.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

8.6 (47.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

3.1 (37.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.4 (54.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.1 (43.0) |

3.1 (37.6) |

1 (34) |

5.6 (42.2) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

8 (46) |

4.4 (39.9) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.3 (2.7) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−12 (10) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

5.3 (41.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−9.5 (14.9) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 256.3 (10.09) |

209.5 (8.25) |

201.7 (7.94) |

140.6 (5.54) |

108.5 (4.27) |

132.3 (5.21) |

157.5 (6.20) |

207.9 (8.19) |

248.1 (9.77) |

268.1 (10.56) |

275.1 (10.83) |

289.9 (11.41) |

2,495.5 (98.26) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19.2 | 17.4 | 17.6 | 14.1 | 13.0 | 13.3 | 15.2 | 16.6 | 18.1 | 18.5 | 18.5 | 19.3 | 200.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79.1 | 77.7 | 74.1 | 69.4 | 68.7 | 72.5 | 75.6 | 76.8 | 77.9 | 78.5 | 79.2 | 80.7 | 75.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 31.8 | 64.4 | 119.2 | 218.7 | 251.9 | 233.5 | 203.1 | 174.2 | 134.3 | 84.2 | 46.2 | 13.4 | 1,574.9 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 15 | 25 | 33 | 50 | 47 | 41 | 36 | 36 | 35 | 27 | 21 | 7 | 31 |

| Source: Seklima[44] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Bergen Airport Flesland 1991-2020 (48 m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.1 (39.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16 (61) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18 (64) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

10.6 (51.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3 (37) |

6.1 (43.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.3 (54.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12 (54) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.6 (36.7) |

7.7 (45.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

6 (43) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

0.3 (32.5) |

5.1 (41.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 204 (8.0) |

168 (6.6) |

165 (6.5) |

110 (4.3) |

88 (3.5) |

100 (3.9) |

121 (4.8) |

175 (6.9) |

208 (8.2) |

230 (9.1) |

241 (9.5) |

219 (8.6) |

2,029 (79.9) |

| Source 1: NOAA (temperatures)[45] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Yr (precipitation)[46] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Bergen Airport Flesland 1981-2010 (48 m, sunshine 1961-1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.9 (62.4) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

22.5 (72.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

17.9 (64.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

33.4 (92.1) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.9 (39.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

10.3 (50.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

2.8 (37.0) |

5.8 (42.4) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

14.5 (58.1) |

11.4 (52.5) |

8.1 (46.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

7.3 (45.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

0.3 (32.5) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

4.7 (40.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.3 (2.7) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

0.8 (33.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−16.3 (2.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 225.5 (8.88) |

169.4 (6.67) |

188.8 (7.43) |

144.5 (5.69) |

110.8 (4.36) |

111.6 (4.39) |

157.0 (6.18) |

189.7 (7.47) |

272.7 (10.74) |

257.5 (10.14) |

296.1 (11.66) |

223.9 (8.81) |

2,347.6 (92.43) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 19.1 | 16.4 | 17.3 | 14.0 | 12.8 | 12.7 | 14.5 | 15.9 | 17.0 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 18.5 | 195.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78 | 76 | 73 | 72 | 72 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 79 | 79 | 78 | 79 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 19 | 56 | 94 | 147 | 186 | 189 | 167 | 144 | 86 | 60 | 27 | 12 | 1,187 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 9 | 22 | 25 | 34 | 35 | 34 | 30 | 30 | 22 | 19 | 12 | 6 | 23 |

| Source 1: NOAA (temperatures)[47] NOAA (humidity and sunshine)[48] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Voodoo Skies for extremes[49] Naturen[50] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

[edit]| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Bryggen in Bergen, built after 1702 | |

| Location | Bergen Municipality, Bergen, Norway |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 59 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Area | 1.196 ha (128,700 sq ft) |

| Website | www |

The city centre of Bergen lies in the west of the municipality, facing the fjord of Byfjorden. It is among a group of mountains known as the Seven Mountains, although the number is a matter of definition. From here, the urban area of Bergen extends to the north, west and south, and to its east is a large mountain massif. Outside the city centre and the surrounding neighbourhoods (i.e. Årstad, inner Laksevåg and Sandviken), the majority of the population lives in relatively sparsely populated residential areas built after 1950. While some are dominated by apartment buildings and modern terraced houses (e.g. Fyllingsdalen), others are dominated by single-family homes.[51]

The oldest part of Bergen is the area around the bay of Vågen in the city centre. Originally centred on the bay's eastern side, Bergen eventually expanded west and southwards. Few buildings from the oldest period remain, the most significant being St Mary's Church from the 12th century. For several hundred years, the extent of the city remained almost constant. The population was stagnant, and the city limits were narrow.[52] In 1702, seven-eighths of the city burned. Most of the old buildings of Bergen, including Bryggen (which was rebuilt in a mediaeval style), were built after the fire. The fire marked a transition from tar covered houses, as well as the remaining log houses, to painted and some brick-covered wooden buildings.[53]

The last half of the 19th century saw a period of rapid expansion and modernisation. The fire of 1855 west of Torgallmenningen led to the development of regularly sized city blocks in this area of the city centre. The city limits were expanded in 1876, and Nygård, Møhlenpris and Sandviken were urbanized with large-scale construction of city blocks housing both the poor and the wealthy.[54] Their architecture is influenced by a variety of styles; historicism, classicism and Art Nouveau.[55] The wealthy built villas between Møhlenpris and Nygård, and on the side of Mount Fløyen; these areas were also added to Bergen in 1876. Simultaneously, an urbanization process was taking place in Solheimsviken in Årstad, at that time outside the Bergen municipality, centred on the large industrial activity in the area.[56] The workers' homes in this area were poorly built, and little remains after large-scale redevelopment in the 1960s–1980s.

After Årstad became a part of Bergen in 1916, a development plan was applied to the new area. Few city blocks akin to those in Nygård and Møhlenpris were planned. Many of the worker class built their own homes, and many small, detached apartment buildings were built. After World War II, Bergen had again run short of land to build on, and, contrary to the original plans, many large apartment buildings were built in Landås in the 1950s and 1960s. Bergen acquired Fyllingsdalen from Fana municipality in 1955. Like similar areas in Oslo (e.g. Lambertseter), Fyllingsdalen was developed into a modern suburb with large apartment buildings, mid-rises, and some single-family homes, in the 1960s and 1970s. Similar developments took place beyond Bergen's city limits, for example in Loddefjord.[57]

At the same time as planned city expansion took place inside Bergen, its extra-municipal suburbs also grew rapidly. Wealthy citizens of Bergen had been living in Fana since the 19th century, but as the city expanded it became more convenient to settle in the municipality. Similar processes took place in Åsane and Laksevåg. Most of the homes in these areas are detached row houses,[clarification needed] single family homes or small apartment buildings.[57] After the surrounding municipalities were merged with Bergen in 1972, expansion has continued in largely the same manner, although the municipality encourages condensing near commercial centres, future Bergen Light Rail stations, and elsewhere.[58][59]

As part of the modernisation wave of the 1950s and 1960s, and due to damage caused by World War II, the city government ambitiously planned redevelopment of many areas in central Bergen. The plans involved demolition of several neighbourhoods of wooden houses, namely Nordnes, Marken, and Stølen. None of the plans was carried out in its original form; the Marken and Stølen redevelopment plans were discarded and that of Nordnes only carried out in the area that had been most damaged by war. The city council of Bergen had in 1964 voted to demolish the entirety of Marken, however, the decision proved to be highly controversial and the decision was reversed in 1974. Bryggen was under threat of being wholly or partly demolished after the fire of 1955, when a large number of the buildings burned to the ground. Instead of being demolished, the remaining buildings were restored and accompanied by reconstructions of some of the burned buildings.[57]

Demolition of old buildings and occasionally whole city blocks is still taking place, the most recent major example being the 2007 razing of Jonsvollskvartalet at Nøstet.[60]

Billboards are banned in the city.[61]

Administration

[edit]The municipality has had a parliamentary government since 2000. Up until then, Bergen had been governed by the city council (formannskap).[62] The government now consists of seven government members called commissioners, and is appointed by the city council, the supreme authority of the city.

The tables below show the current and historical composition of the council by political party.

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 13 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 7 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 4 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 18 | |

| Industry and Business Party (Industri‑ og Næringspartiet) | 3 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 2 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 3 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 2 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 7 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Bergen List (Bergenslisten) | 4 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 13 | |

| People's Action No to More Road Tolls (Folkeaksjonen nei til mer bompenger) | 11 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 3 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 7 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 14 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 2 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 3 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 4 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 6 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 28 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 6 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 4 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 15 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 6 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 6 | |

| Total number of members: | 73 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 19 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 7 | |

| Green Party (Miljøpartiet De Grønne) | 1 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 24 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 3 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 5 | |

| City Air List (Byluftlisten) | 1 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 16 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 14 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 18 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Party (Rødt) | 3 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 2 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 4 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 15 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 12 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 18 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 3 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 8 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 2 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 20 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 13 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 14 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 2 | |

| Total number of members: | 67 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 24 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 14 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 19 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 9 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 4 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 3 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 6 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 30 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 10 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 16 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Pensioners' Party (Pensjonistpartiet) | 3 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 2 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 4 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 10 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 29 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 17 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 22 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Joint list of the Liberal Party (Venstre) and Liberal People's Party (Liberale Folkepartiet) |

4 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 30 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 9 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 27 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 8 | |

| Liberal People's Party (Liberale Folkepartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 1 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 26 | |

| Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) | 4 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 35 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 9 | |

| New People's Party (Nye Folkepartiet) | 1 | |

| Red Electoral Alliance (Rød Valgallianse) | 1 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 1 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 3 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 5 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 29 | |

| Anders Lange's Party (Anders Langes parti) | 2 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 28 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 11 | |

| New People's Party (Nye Folkepartiet) | 5 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 2 | |

| Socialist Left Party (Sosialistisk Venstreparti) | 5 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 33 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 20 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 3 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Centre Party (Senterpartiet) | 3 | |

| Socialist People's Party (Sosialistisk Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 15 | |

| Total number of members: | 85 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 36 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 20 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 1 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 5 | |

| Socialist People's Party (Sosialistisk Folkeparti) | 3 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 12 | |

| Total number of members: | 77 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 37 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 22 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 1 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 4 | |

| Socialist People's Party (Sosialistisk Folkeparti) | 2 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 11 | |

| Total number of members: | 77 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 34 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 20 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 4 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 12 | |

| Total number of members: | 77 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 34 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 18 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 6 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 12 | |

| Total number of members: | 77 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 35 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 15 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 6 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 13 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 25 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 14 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 13 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 7 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 16 | |

| Local List(s) (Lokale lister) | 1 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 24 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 11 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 21 | |

| Christian Democratic Party (Kristelig Folkeparti) | 6 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 12 | |

| Local List(s) (Lokale lister) | 2 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 27 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 7 | |

| Free-minded People's Party (Frisinnede Folkeparti) | 5 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 13 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 7 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 17 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Note: Due to the German occupation of Norway during World War II, no elections were held for new municipal councils until after the war ended in 1945. | ||

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 27 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 8 | |

| Free-minded People's Party (Frisinnede Folkeparti) | 9 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 10 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 9 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 13 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 21 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 4 | |

| Free-minded People's Party (Frisinnede Folkeparti) | 13 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 13 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 11 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 14 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 21 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 6 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 16 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 11 | |

| Joint list of the Conservative Party (Høyre) and the Free-minded Liberal Party (Frisinnede Venstre) | 22 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 2 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 6 | |

| Communist Party (Kommunistiske Parti) | 22 | |

| Social Democratic Labour Party (Socialdemokratiske Arbeiderparti) |

8 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 9 | |

| Joint list of the Conservative Party (Høyre) and the Free-minded Liberal Party (Frisinnede Venstre) | 26 | |

| Homeowners' list (Huseiere liste) | 3 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 28 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 6 | |

| Social Democratic Labour Party (Socialdemokratiske Arbeiderparti) |

6 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 5 | |

| Joint list of the Conservative Party (Høyre) and the Free-minded Liberal Party (Frisinnede Venstre) | 26 | |

| Local List(s) (Lokale lister) | 5 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

| Party name (in Norwegian) | Number of representatives | |

|---|---|---|

| Labour Party (Arbeiderpartiet) | 24 | |

| Temperance Party (Avholdspartiet) | 8 | |

| Free-minded Liberal Party (Frisinnede Venstre) | 3 | |

| Conservative Party (Høyre) | 28 | |

| Liberal Party (Venstre) | 7 | |

| Local List(s) (Lokale lister) | 6 | |

| Total number of members: | 76 | |

Boroughs

[edit]

Bergen is divided into eight boroughs,[88] as seen on the map to the right. Clockwise, starting with the northernmost, the boroughs are Åsane, Arna, Fana, Ytrebygda, Fyllingsdalen, Laksevåg, Årstad and Bergenhus. The city centre is in Bergenhus. Parts of Fana, Ytrebygda, Åsane and Arna are not part of the Bergen urban area, explaining why the municipality has approximately 20,000 more inhabitants than the urban area.[89]

Local borough administrations have varied since Bergen's expansion in 1972. From 1974, each borough had a politically chosen administration. From 1989, Bergen was divided into 12 health and social districts, each locally administered. From 2000 to 2004, the former organizational form with eight politically chosen local administrations was again in use and from 2008 through to 2010, a similar form existed where the local administrations had less power than previously.[90]

| Borough | Population[91] | % | Area (km2) | % | Density (/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arna | 14,020 | 4.9 | 102.44 | 22.0 | 123 |

| Bergenhus1 | 43,218 | 14.8 | 26.58 | 5.7 | 4.415 |

| Fana | 44,600 | 14.8 | 159.70 | 34.3 | 239 |

| Fyllingsdalen | 30,614 | 11.1 | 18.84 | 4.0 | 1.530 |

| Laksevåg | 40,646 | 14.8 | 32.72 | 7.0 | 1.173 |

| Ytrebygda | 31,676 | 9.9 | 39.61 | 8.5 | 649 |

| Årstad2 | 42,673 | 14.5 | 14.78 | 3.2 | 4.440 |

| Åsane | 44,233 | 15.2 | 71.01 | 15.2 | 556 |

| Not stated | 260 | ||||

| Total | 291,940 | 100 | 465.68 | 100 | 559 |

(Pertaining to the table above: The acreage figures include fresh water and uninhabited mountain areas, except:

1 1 The borough Bergenhus is 8.73 km2 (3.37 sq mi), the rest is water and uninhabited mountain areas.

2 2 The borough Årstad is 8.47 km2 (3.27 sq mi), the rest is water and uninhabited mountain areas.)

Former borough: Sentrum

Sentrum (literally, "Centre") was a borough (with the same name as a present-day neighbourhood). The borough was numbered 01, and its perimeter was from Store Lungegårdsvann and Strømmen along Puddefjorden around Nordnes and over to Skuteviken, up Mt. Fløyen east of Langelivannet, on to Skansemyren and over Forskjønnelsen to Store Lungegårdsvann, south of the railroad tracks.[92]

The population of the (now defunct) borough, numbered in 1994 more than 18,000 people.[92]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1769 | 18,827 | — |

| 1801 | 24,136 | +28.2% |

| 1815 | 23,123 | −4.2% |

| 1825 | 28,195 | +21.9% |

| 1835 | 31,525 | +11.8% |

| 1845 | 33,145 | +5.1% |

| 1855 | 37,015 | +11.7% |

| 1865 | 42,994 | +16.2% |

| 1875 | 54,436 | +26.6% |

| 1890 | 72,879 | +33.9% |

| 1900 | 94,485 | +29.6% |

| 1910 | 104,224 | +10.3% |

| 1920 | 118,490 | +13.7% |

| 1930 | 129,118 | +9.0% |

| 1946 | 153,446 | +18.8% |

| 1950 | 162,381 | +5.8% |

| 1960 | 185,822 | +14.4% |

| 1970 | 209,066 | +12.5% |

| 1980 | 207,674 | −0.7% |

| 1990 | 212,944 | +2.5% |

| 2001 | 232,989 | +9.4% |

| 2011 | 260,392 | +11.8% |

| 2021 | 285,601 | +9.7% |

| Source: Statistics Norway.[93][94] Note: The municipalities of Arna, Fana, Laksevåg and Åsane were merged with Bergen 1 January 1972. | ||

As of the start of 2022[update], the municipality had a population of 286,930,[4] making the population density 599 people per km2. Urban areas outside the city limits, as defined by Statistics Norway, consist of Indre Arna (6,536 residents on 1 January 2012), Fanahammeren (3,690), Ytre Arna (2,626), Hylkje (2,277) and Espeland (2,182).[95]

| Ancestry | Number |

|---|---|

| Total | 58,175 |

| 6,755 | |

| 2,384 | |

| 2,151 | |

| 2,064 | |

| 2,010 | |

| 1,904 | |

| 1,769 | |

| 1,691 | |

| 1,509 | |

| 1,415 |

As of 2007, people of Norwegian origin (those who have two parents born in Norway) make up 84.5% of Bergen's residents. In addition, 8.1% were first or second generation immigrants of Western background and 7.4% were first or second generation immigrants of non-Western background.[97] The population grew by 4,549 people in 2009, a growth rate of 1.8%. Ninety-six percent of the population lives in urban areas. As of 2002, the average gross income for men above the age of 17 is 426,000 Norwegian krone (NOK), the average gross income for women above the age of 17 is NOK 238,000, with the total average gross income being NOK 330,000.[97] In 2007, there were 104.6 men for every 100 women in the age group of 20–39.[97] 22.8% of the population were under 17 years of age, while 4.5% were 80 and above.

The immigrant population (those with two foreign-born parents) in Bergen, includes 42,169 individuals with backgrounds from more than 200 countries representing 15.5% of the city's population (2014). Of these, 50.2% have background from Europe, 28.9% from Asia, 13.1% from Africa, 5.5% from Latin America, 1.9% from North America, and 0.4% from Oceania. The immigrant population in Bergen in the period 1993–2008 increased by 119.7%, while the ethnic Norwegian population grew by 8.1% during the same period. The national average is 138.0% and 4.2%. The immigrant population has thus accounted for 43.6% of Bergen's population growth and 60.8% of Norway's population growth during the period 1993–2008, compared with 84.5% in Oslo.[98]

The immigrant population in Bergen has changed a lot since 1970. As of 1 January 1986, there were 2,870 people with a non-Western immigrant background in Bergen. In 2006, this figure had increased to 14,630, so the non-Western immigrant population in Bergen was five times higher than in 1986. This is a slightly slower growth than the national average, which has sextupled during the same period. Also in relation to the total population in Bergen, the proportion of non-Westerns increased significantly. In 1986, the proportion of the total population in the municipality of non-Western background was 3.6%. In January 2006, people with a non-Western immigrant background accounted for 6 percent of the population in Bergen. The share of Western immigrants has remained stable at around 2% in the period. The number of Poles in Bergen rose from 697 in 2006 to 3,128 in 2010.[99]

As of 2022, immigrants of non-Western origin and their children enumerated 30,540, and made up an estimated 11% of Bergen's population. Immigrants of Western origin and their children enumerated 22,954, and made up an estimated 9% of Bergen's population.[100][101]

The Church of Norway is the largest denomination in Bergen, with 201,006 (79.74%) registered adherents in 2012. Bergen is the seat of the Diocese of Bjørgvin with Bergen Cathedral as its centrepiece, while St John's Church is the city's most prominent. As of 2012, the state church is followed by 52,059 irreligious,[102] 4,947 members of various Protestant free churches, 3,873 actively registered Catholics,[103][104] 2,707 registered Muslims, 816 registered Hindus, 255 registered Russian Orthodox and 147 registered Oriental Orthodox.

Education

[edit]

There are 64 elementary schools,[105] 18 lower secondary schools[106] and 20 upper secondary schools[107] in Bergen, as well as 11 combined elementary and lower secondary schools.[108] Bergen Cathedral School is the oldest school in Bergen and was founded by Pope Adrian IV in 1153.[109]

The "Bergen School of Meteorology" was developed at the Geophysical Institute beginning in 1917, the Norwegian School of Economics was founded in 1936, and the University of Bergen in 1946.[110]

The University of Bergen has 16,000 students and 3,000 staff, making it the third-largest educational institution in Norway.[111] Research in Bergen dates back to activity at Bergen Museum in 1825, although the university was not founded until 1946. The university has a broad range of courses and research in academic fields and three national centres of excellence, in climate research, petroleum research and medieval studies.[112] The main campus is in the city centre. The university co-operates with Haukeland University Hospital within medical research. The Chr. Michelsen Institute is an independent research foundation established in 1930 focusing on human rights and development issues.[113]

The Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, which has its main campus in Kronstad, has 16,000 students and 1800 staff.[114] It focuses on professional education, such as teaching, healthcare and engineering. The college was created through amalgamation in 1994; campuses are spread around town but will be co-located at Kronstad. The Norwegian School of Economics is in outer Sandviken and is the leading business school in Norway,[115] having produced three Economy Nobel Prize laureates.[116] The school has more than 3,000 students and approximately 400 staff.[117] Other tertiary education institutions include the Bergen School of Architecture, the Bergen National Academy of the Arts, in the city centre with 300 students,[118] and the Norwegian Naval Academy in Laksevåg. The Norwegian Institute of Marine Research has been in Bergen since 1900. It provides research and advice relating to ecosystems and aquaculture. It has a staff of 700 people.[119]

Economy

[edit]

In August 2004, Time magazine named the city one of Europe's 14 "secret capitals"[120] where Bergen's capital reign is acknowledged within maritime businesses and activities such as aquaculture and marine research, with the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) (the second-largest oceanography research centre in Europe) as a leading institution. Some of the world's largest aquaculture companies, such as Mowi and Lerøy are headquartered in the city. Shipowners based in Bergen control a significant portion of the Norwegian merchant fleet, including shipowners such as Wilson, Odfjell and Gearbulk. The city has a large presence of financial institutions. Banks Sbanken and Sparebanken Vest are headquartered in the city. The Norwegian branches of insurance companies Tryg, DNB Livsforsikring and Nordea Liv are headquartered in Bergen, along with a significant presence of marine insurance companies, including Norwegian Hull Club. A number of banks maintain large corporate banking divisions in connection with shipping and aquaculture in the city.

Bergen is the main base for the Royal Norwegian Navy (at Haakonsvern) and its international airport Flesland is the main heliport for the Norwegian North Sea oil and gas industry, from where thousands of offshore workers commute to their work places onboard oil and gas rigs and platforms.[121]

Tourism is an important income source for the city. The hotels in the city may be full at times,[122][123] due to the increasing number of tourists and conferences. Bergen is recognized as the unofficial capital of the region known as Western Norway, and recognized and marketed as the gateway city to the world-famous fjords of Norway, and for that reason, it has become Norway's largest – and one of Europe's largest – cruise ship ports of call.[124]

Transport

[edit]

Air

[edit]Bergen Airport, Flesland, is 18 kilometres (11 mi) from the city centre, at Flesland.[125] In 2013, the Avinor-operated airport served 6 million passengers. The airport serves as a hub for Scandinavian Airlines, Norwegian Air Shuttle and Widerøe; there are direct flights to 20 domestic and 53 international destinations.[126]

Sea

[edit]Bergen Port, operated by Bergen Port Authority, is the largest seaport in Norway.[127] In 2011, the port saw 264 cruise calls with 350,248 visitors,[128] In 2009, the port handled 56 million tonnes of cargo, making it the ninth-busiest cargo port in Europe.[129] There are plans to move the port out of the city centre, but no location has been chosen.[130] Fjord Line operates a cruiseferry service to Hirtshals, Denmark. Bergen is the southern terminus of Hurtigruten, the Coastal Express, which operates with daily services along the coast to Kirkenes.[125] Passenger catamarans run from Bergen south to Leirvik and Sunnhordland, and north to Sognefjord and Nordfjord.[131]

The port includes three large power connections that allow ships to turn off their engines whilst docked (known as "cold ironing")[132]

Road

[edit]The city centre is surrounded by an electronic toll collection ring using the Autopass system.[133] The main motorways consist of E39, which runs north–south through the municipality, E16, which runs eastwards, and National Road 555, which runs westwards. There are four major bridges connecting Bergen to neighbouring municipalities: the Nordhordland Bridge,[134] the Askøy Bridge,[135] the Sotra Bridge[136] and the Osterøy Bridge. Bergen connects to the island of Bjorøy via the subsea Bjorøy Tunnel.[137]

Rail

[edit]Bergen Station is the terminus of the Bergen Line, which runs 496 kilometres (308 mi) to Oslo.[138] Vy operates express trains to Oslo and the Bergen Commuter Rail to Voss. Between Bergen and Arna Station, the train runs about every 30 minutes through the Ulriken Tunnel; there is no corresponding road tunnel, forcing road vehicles to travel via Åsane or Nesttun.[139]

Lightrail

[edit]

Bergen is one of the smallest cities in Europe to have both tram and trolleybus electric urban transport systems simultaneously [citation needed]. Public transport in Hordaland is managed by Skyss, which operates an extensive city bus network in Bergen and to many neighbouring municipalities,[140] including one route which operates as a trolleybus. The trolleybus system in Bergen is the only one still in operation in Norway and one of two trolleybus systems in Scandinavia.[141]

The modern tram Bergen Light Rail (Bybanen) opened between the city centre and Nesttun in 2010,[142] extended to Rådal (Lagunen Storsenter) in 2013 and to the Bergen airport Flesland in 2017.[143] Extensions to other boroughs may occur later.[144]

Fløibanen is a funicular which runs from the city centre to Mount Fløyen and Ulriksbanen is an aerial tramway which runs to Mount Ulriken.

Culture and sports

[edit]

Bergens Tidende (BT) and Bergensavisen (BA) are the largest newspapers, with circulations of 87,076 and 30,719 in 2006,[145] BT is a regional newspaper covering all of Vestland, while BA focuses on metropolitan Bergen. Other newspapers published in Bergen include the Christian national Dagen, with a circulation of 8.936,[145] and TradeWinds, an international shipping newspaper. Local newspapers are Fanaposten for Fana, Sydvesten for Laksevåg and Fyllingsdalen and Bygdanytt for Arna and the neighbouring municipality Osterøy.[145] TV 2, Norway's largest private television company, is based in Bergen.

The 1,500-seat Grieg Hall is the city's main cultural venue,[146] and home of the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, founded in 1765,[147] and the Bergen Woodwind Quintet. The city also features Carte Blanche, the Norwegian national company of contemporary dance. The annual Bergen International Festival is the main cultural festival, which is supplemented by the Bergen International Film Festival. Two internationally renowned composers from Bergen are Edvard Grieg and Ole Bull. Grieg's home, Troldhaugen, has been converted to a museum. During the 1990s and early 2000s, Bergen produced a series of successful pop, rock and black metal artists,[148] collectively known as the Bergen Wave.[149][150]

Den Nationale Scene is Bergen's main theatre. Founded in 1850, it had Henrik Ibsen as one of its first in-house playwrights and art directors. Bergen's contemporary art scene is centred on BIT Teatergarasjen, Bergen Kunsthall, United Sardines Factory (USF) and Bergen Center for Electronic Arts (BEK). Bergen was a European Capital of Culture in 2000.[151] Buekorps is a unique feature of Bergen culture, consisting of boys aged from 7 to 21 parading with imitation weapons and snare drums.[152][153] The city's Hanseatic heritage is documented in the Hanseatic Museum at Bryggen.[154]

SK Brann is Bergen's premier football team; founded in 1908, they have played in the top flight for Norwegian men's football, Eliteserien, for 67 out of 80 seasons since its establishment in 1937, the second most of any club. The team were the football champions in 1961–1962, 1963, and 2007,[155] and reached the quarter-finals of the Cup Winners' Cup in 1996–1997. They have also won the Norwegian Football Cup seven times, most recently in the 2022 season. Brann play their home games at the 16,750-seat Brann Stadion.[156] Åsane is the city's second-best team, playing in the First Division at Åsane Arena. Now-defunct Fyllingen played in the top flight in 1990, 1991 and 1993. Brann and Åsane also play in the women's top flight, Toppserien, along with Arna-Bjørnar. Brann have won the league twice (once as IL Sandviken), and the Norwegian Women's Cup once.

Bergen IK is the premier men's ice hockey team, playing at Bergenshallen in the First Division. Tertnes play in the Women's Premier Handball League, and Fyllingen in the Men's Premier Handball League. In athletics, the city is dominated by IL Norna-Salhus, IL Gular and FIK BFG Fana, formerly also Norrøna IL and TIF Viking. The Bergen Storm are an American football team that plays matches at Varden Kunstgress and plays in the second division of the Norwegian league.

Bergensk is the native dialect of Bergen. It was strongly influenced by Low German-speaking merchants from the mid-14th to mid-18th centuries. During the Dano-Norwegian period from 1536 to 1814, Bergen was more influenced by Danish than other areas of Norway. The Danish influence removed the female grammatical gender in the 16th century, making Bergensk one of very few Norwegian dialects with only two instead of three grammatical genders. The Rs are uvular trills, as in French, which probably spread to Bergen some time in the 18th century, overtaking the alveolar trill in the time span of two to three generations. Owing to an improved literacy rate, Bergensk was influenced by riksmål and bokmål in the 19th and 20th centuries. This led to large parts of the German-inspired vocabulary disappearing and pronunciations shifting slightly towards East Norwegian.[157]

The 1986 edition of the Eurovision Song Contest took place in Bergen. Bergen was the host city for the 2017 UCI Road World Championships. The city is also a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network in the category of gastronomy since 2015.[158]

Music

[edit]

Bergen has been the home of several notable alternative bands, collectively referred to as the Bergen Wave. These bands include Röyksopp and Kings of Convenience on the small, Bergen-based record label Tellé Records, as well as related side-projects, such as The Whitest Boy Alive, Kommode, and Visekongene on independent labels. Other internationally well-received artists also originating from Bergen include Aurora, Sondre Lerche, Kygo, Boy Pablo and Alan Walker.

Bergen is also known as the "black metal capital of Norway", due to its role in the early Norwegian black metal scene and the amount of acts to come from the city in the early 1990s. Also the singer Einar Selvik of the band Wardruna was born in Bergen and became famous thanks to the TV series Vikings.[159]

Bergen is also the birthplace of composer Edvard Grieg. The biggest music festival in the city is Bergenfest.

Street art

[edit]Bergen is considered to be the street art capital of Norway.[160] Famed artist Banksy visited the city in 2000[161] and inspired many to start creating street art. Soon after, the city brought up the most famous street artist in Norway: Dolk.[162][163] His art can still be seen in several places in the city, and in 2009 the city council choose to preserve Dolk's work "Spray" with protective glass.[164] In 2011, Bergen council launched a plan of action for street art in Bergen from 2011 to 2015 to ensure that "Bergen will lead the fashion for street art as an expression both in Norway and Scandinavia".[165]

The Madam Felle (1831–1908) monument in Sandviken, is in honour of a Norwegian woman of German origin, who in the mid-19th century managed, against the will of the council, to maintain a counter of beer. A well-known restaurant of the same name is now elsewhere in Bergen. The monument was erected in 1990 by sculptor Kari Rolfsen, supported by an anonymous donor. Madam Felle, civil name Oline Fell, was posthumously remembered in a popular song, possibly originally a folksong,[166] "Kjenner Dokker Madam Felle?" by Lothar Lindtner and Rolf Berntzen on an album in 1977.

Parks and bathing places

[edit]Parks

[edit]- Nygårdsparken

- Nordnesparken

- Byparken

- Teaterparken

- Meyermarken

- Gamlehaugen

- Storetveitmarken

- Olsvikparken

Bathing places

[edit]- Kyrkjetangen

- Tennebekktjørna

- Helleneset

- Nordnes Sjøbad

- Grønnskjæret

- Hordvikhavn

- Skjoldabukta

- Marineholmen Sandstrand

Media

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2023) |

Newspapers

[edit]- Arbeidet (1893–1949)

- Bergens Adressecontoirs Efterretninger (1765-1889)

- Bergens Aftenblad (1880-1942)

- Bergens Social-Demokrat (1922-1927)

- Bergens Stiftstidende (1840-1855)

- Bergens Tidende (1868–)

- Bergensavisen (1927–)

- Blondebladet (1914-1935)

- Bygdanytt (1951-)

- Dagen (1919-)

- Fanaposten (1978-)

- Fjordaposten (1923-1940)

- Gula Tidend (1904-1996)

- Morgenavisen (1902-1984)

- Norge Idag (1999-)

- Studvest (1945-)

- Vestlandsbonden (1904-1915)

Other Publications

[edit]- Bergen Byleksikon, Encyclopedia of Bergen

- Naturen, Science magazine

- Samtiden, Political and literary magazine

- Urda (journal), Former history magazine

- Vi over 60, Magazine for over 60s

TV Channels

[edit]- Bergen Student-TV, Student television channel

- TV 2 Direkte, TV channel based in Bergen

Neighbourhoods

[edit]The traditional neighbourhoods of Bergen include Bryggen, Eidemarken, Engen, Fjellet, Kalfaret, Ladegården, Løvstakksiden,[167] Marken, Minde, Møhlenpris, Nordnes, Nygård, Nøstet, Sandviken, Sentrum, Skansen, Skuteviken, Strandsiden, Stølen, Sydnes, Verftet, Vågsbunnen, Wergeland,[168] and Ytre Sandviken.

Grunnkretser

[edit]The various addresses in Bergen, each belong to one of the various grunnkrets.

International relations

[edit]Each year Bergen sells the Christmas tree seen in Newcastle's Haymarket as a sign of the ongoing friendship between the sister cities, which were connected by a ferry service from 1890 to 2008.[169] The Nordic friendship cities of Bergen, Gothenburg, Turku and Aarhus arrange inter-Nordic camps each year by registering tenth-grade school classes from each of the other cities to school camps, for a profit. Bergen received a totem pole as a gift of friendship from the city of Seattle on the city's 900th anniversary in 1970. It is now placed in the Nordnes Park and gazes out over the sea towards the friendship city far to the west.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Gallery

[edit]-

Kjøttbasaren, an iconic building in Bergen from 1876

-

Bergen Courthouse

-

View of the Musikkpaviljongen

-

Zachariasbryggen

-

Bergen Storsenter, shopping mall in central Bergen

Notable people from Bergen

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by metropolitan regions". ec.europa.eu.

- ^ "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- ^ Bolstad, Erik; Thorsnæs, Geir, eds. (9 January 2024). "Kommunenummer". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian). Foreningen Store norske leksikon.

- ^ a b "01222: Population and changes during the quarter, by region, contents and quarter" (in Norwegian Bokmål). SSB. 19 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2025.

- ^ Heggemsnes, Nils (26 September 2012). "Bergen Havn". Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ a b "Cruisestatistikk". Cruise (in Norwegian Bokmål). Port of Bergen. 2016. Archived from the original on 26 May 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ Brekke, Nils Georg (1993). Kulturhistorisk vegbok Hordaland (in Norwegian). Bergen: Hordaland Fylkeskommune. ISBN 82-7326-026-7.

- ^ Elisabeth Farstad (2007). "Om kommunen" (in Norwegian Bokmål). Bergen kommune. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- ^ Hella, Asle (7 June 2004). "Bergens historie må skrives om". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål).

- ^ Marguerite Ragnow (2007). "Cod". Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ^ a b Tom R. Hjertholm (16 December 2013). "- Tørrfisken vender hjem". Bergensavisen.

- ^ Alf Ragnar Nielssen (1 January 1950). "Indigenous and Early Fisheries in North-Norway" (PDF). The Sea in European History. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Anette Skogseth Clausen. "7. oktober 1754 – fra et hanseatisk kontor til et norsk kontor med hanseater" (in Norwegian Bokmål). Arkivverket. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ Østby Pedersen, Nina (2005). "Scottish Immigration to Bergen in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries". In Grosjean, Alexia; Murdoch, Steve (eds.). Scottish Communities Abroad in the Early Modern Period. Brill. pp. 136–168. doi:10.1163/9789047407157_010. ISBN 978-90-474-0715-7.

- ^ UNESCO (2007). "World Heritage List". Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ^ Carl Hecker, Justus Friedrich (1833). The Black Death in the Fourteenth Century.

- ^ Knight, Charles, ed. (1847). The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge. Vol. III. London: Charles Knight. p. 211.

- ^ Downing Kendrick, Thomas (2004). A History of the Vikings. Courier Corporation. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-486-43396-7.

- ^ "The fire of 1702". kulturpunkt.org. Bergen City Museum. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Innvandring 1600–2000, Arkivenes dag 2002" (in Norwegian Bokmål). Arkivverket. Archived from the original on 6 December 2002. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ Fossen, Anders Bjarne. "Jørgen Thormøhlen". In Helle, Knut (ed.). Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Ivan Kristoffersen (2003). "Historien om Norge i nord" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ "Distriktsinndeling og navn" (in Norwegian). Fornyings- og administrasjonsdepartementet. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2007.

- ^ Jukvam, Dag (1999). Historisk oversikt over endringer i kommune- og fylkesinndelingen (PDF) (in Norwegian). Statistisk sentralbyrå. ISBN 9788253746845.

- ^ Jenny Heggsvik; Lars Borgersrud; August Rathke; Egil Christophersen; Ole-Jacob Abraham. "Prosjektbeskrivelse for det historiske forskningsprosjektet SABORG I BERGEN". Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ NRK (21 November 2017). "The Isdalen Mystery". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ McCarthy, Marit Higraff and Neil (25 June 2019). "Death in Ice Valley: New clues in a Norwegian mystery". Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Tønder, Finn Bjørn (26 November 2002). "Viktig nyhet om Isdalskvinnen" [Important news about Isdal Woman]. Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ Bergen Kommune (2007). "Styringssystemet i Bergen kommune" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ^ Brekke, Nils Georg (1993). Kulturhistorisk vegbok Hordaland (in Norwegian). Bergen: Hordaland Fylkeskommune. p. 252. ISBN 82-7326-026-7.

- ^ "Bjørgvin bispedøme" (in Norwegian). Scandion.no. 2004. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Gunhild Agdesteen (2007). "I den syvende himmel". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ^ "Norwegian Mountains: Gullfjellstoppen". Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ "Sunrise and sunset times in Bergen, June". Timeanddate.com. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ ANB-NTB (2007). "Stopp for nedbørsrekord" (in Norwegian). siste.no. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ Meze-Hausken, Elisabeth (October 2007). "Seasons in the sun—weather and climate front-page news stories in Europe's rainiest city, Bergen, Norway". International Journal of Biometeorology. 52 (1): 17–31. Bibcode:2007IJBm...52...17M. doi:10.1007/s00484-006-0064-5. hdl:1956/2114. ISSN 1432-1254. PMID 17245564. S2CID 29081365.

- ^ "Europe and the United Kingdom Average Yearly Annual Precipitation". eldoradoweather.com. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "Siste frostnatt om våren". 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Første frostnatt". 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Nå er 33,4 den nye varmerekorden i Bergen". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). 26 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Bjørbæk, G (2003). Norsk vær i 110 år. N.W. DAMM & Sønn. p. 260. ISBN 8204086954.

- ^ "Over 1600 soltimer i Bergen i fjor trass i elendig vær i skoleferien". 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Årstadposten – Nytt fra Årstad siden 1993". Arstadposten.no. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2024.

- ^ seklima.met.no

- ^ "Index of /Archive/Arc0216/0253808/1.1/Data/0-data/Region-6-WMO-Normals-9120/Norway/CSV".

- ^ "Historiske værdata for Flesland som graf - Siste 13 måneder".

- ^ "NOAA stats – Bergen". NOAA. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ^ "BERGEN – FLORIDA Climate Normals: 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ^ "Voodoo Skies – Bergen Monthly Temperature weather history". Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- ^ Mamen, J (2008). "Dypdykk i klimadatabasen. Rekorder og kuriositeter fra Meteorologisk institutts klimaarkiv". Naturen (6): 250.

- ^ Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. p. 27. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- ^ Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. p. 23. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- ^ Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. p. 25. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- ^ Østerbø, Kjell (23 September 2007). "Da rike og fattige fikk sine strøk". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. pp. 25–26. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- ^ Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. pp. 26–27. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- ^ a b c Hagen Hartvedt, Gunnar (1994). "Bergen". Bergen Byleksikon (1st ed.). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. pp. 9–61. ISBN 82-573-0485-9.

- ^ Mæland, Pål Andreas (16 May 2008). "Nå kommer slangen til Paradis". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Røyrane, Eva (9 May 2007). "Bergen bygges tettere". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Okkenhaug, Liv Solli (21 April 2007). "Rev de siste husene". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ Patowary, Kaushik (20 July 2013). "São Paulo: The City With No Outdoor Advertisements". AmusingPlanet.

- ^ "Styringssystem" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalg 2023 - Vestland". Valgdirektoratet. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalg 2019 – Vestland". Valgdirektoratet. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d "Table: 04813: Members of the local councils, by party/electoral list at the Municipal Council election (M)" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalg 2011 – Hordaland". Valgdirektoratet. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1995" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1996. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1991" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1993. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1987" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1988. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1983" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo-Kongsvinger: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1984. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunestyrevalget 1979" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1979. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1975" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1977. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1972" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1973. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1967" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1967. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene 1963" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1964. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1959" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1960. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1955" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1957. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1951" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1952. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1947" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1948. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1945" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1947. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1937" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1938. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1934" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1935. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1931" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1932. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1928" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1929. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1925" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1926. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1922" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1923. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Kommunevalgene og Ordførervalgene 1919" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo: Statistisk sentralbyrå. 1920. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Statistics Norway (2004). "Bydeler i Oslo, Bergen, Stavanger og Trondheim" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 3 September 2007. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- ^ says, suNeil (29 October 2019). "The History of Bergen". Life in Norway. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ "Lokaldemokratiets utvikling 1814 – 2014". Bergen kommune (in Norwegian Bokmål). Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Bergen kommune - Folketall per 1. januar 2024". Bergen kommune. 1 January 2024. Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ a b Hartvedt, Gunnar Hagen; Skreien, Norvall (2009) [25 January 2001]. "Bergen byleksikon" (3 ed.).

- ^ "Microsoft Word - FOB-Hefte.doc" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Tabell 6 Folkemengde per 1. januar, etter fylke og kommune. Registrert 2009. Framskrevet 2010–2030, alternativ MMMM" (in Norwegian). Ssb.no. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ "Urban settlements. Population and area, by municipality. 1 January 2012". Statistics Norway. 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "09817: Innvandrere og norskfødte med innvandrerforeldre, etter landbakgrunn, statistikkvariabel, år og region" (in Norwegian). Statistisk sentralbyrå (Statistics Norway). Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b c "SSB: Tall om Bergen kommune" (in Norwegian). Statistics Norway. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ^ "Statistics Norway". Stat Bank. Archived from the original on 26 May 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ Immigrant population in Bergen[dead link]

- ^ "09817: Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents by immigration category, in total and separately, country background and percentages of the population (M) 2010 - 2023. Statbank Norway". SSB. Retrieved 30 October 2023.

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents". SSB. Retrieved 31 October 2023.

- ^ "Bergen Moské størst av trussamfunna i 2009". Fylkesmannen.no. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "Kommuner med minst 50 katolikker pr. 31.12.2003 — den katolske kirke". Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- ^ Marifjæren, Per; Aarnes, Helle (13 January 2008). "Polakkene fyller St. Paul". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- ^ "Oversikt over barneskoler" (in Norwegian). Bergen kommune. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 September 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.