Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

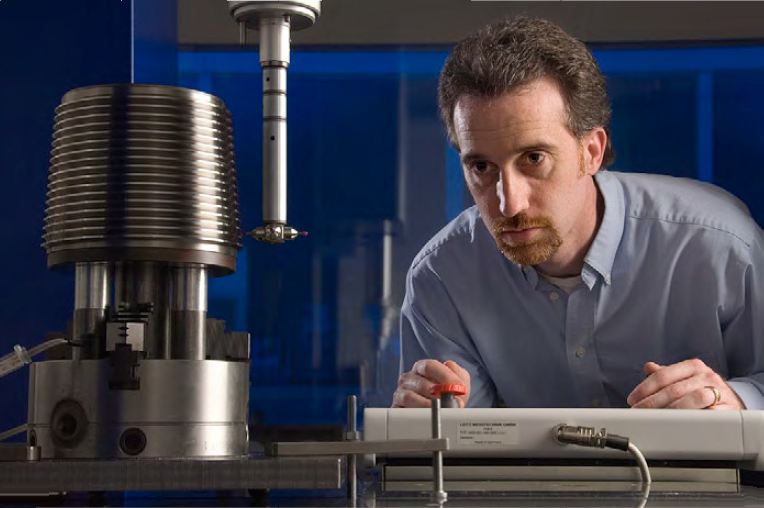

Precision engineering

View on Wikipedia

Precision engineering is a subdiscipline of electrical engineering, software engineering, electronics engineering, mechanical engineering, and optical engineering concerned with designing machines, fixtures, and other structures that have exceptionally low tolerances, are repeatable, and are stable over time. These approaches have applications in machine tools, MEMS, NEMS, optoelectronics design, and many other fields.

Precision engineering is a branch of engineering that focuses on the design, development and manufacture of product with high levels of accuracy and repeatability.

It involves the use of advanced technologies and techniques to achieve tight tolerance and dimensional control in the manufacturing process.

Overview

[edit]Professors Hiromu Nakazawa and Pat McKeown provide the following list of goals for precision engineering:

- Create a highly precise movement.

- Reduce the dispersion of the product's or part's function.

- Eliminate fitting and promote assembly, especially automatic assembly.

- Reduce the initial cost.

- Reduce the running cost.

- Extend the life span.

- Enable the design safety factor to be lowered.

- Improve interchangeability of components so that corresponding parts made by other factories or firms can be used in their place.

- Improve quality control through higher machine accuracy capabilities and hence reduce scrap, rework, and conventional inspection.

- Achieve a greater wear/fatigue life of components.

- Make functions independent of one another.

- Achieve greater miniaturization and packing densities.

- Achieve further advances in technology and the underlying sciences.[2]

Technical Societies

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Institute of Standards and Technology

- ^ NIST Manufacturing Engineering (2008).NIST Programs of the Manufacturing Engineering Laboratory. March 2008.

- ^ Venkatesh, V. C. and Izman, Sudin, Precision Engineering, Tata McGraw-Hill Publishing Company Limited, 2007, page 6.