Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Counterintelligence

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Intelligence field and Intelligence |

|---|

|

Counterintelligence (counter-intelligence) or counterespionage (counter-espionage) is any activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service.[1] It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or other intelligence activities conducted by, for, or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations or persons.

Many countries will have multiple organizations focusing on a different aspect of counterintelligence, such as domestic, international, and counter-terrorism. Some states will formalize it as part of the police structure, such as the United States' Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Others will establish independent bodies, such as the United Kingdom's MI5, others have both intelligence and counterintelligence grouped under the same agency, like the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS).

History

[edit]

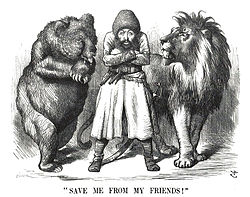

Modern tactics of espionage and dedicated government intelligence agencies developed over the course of the late-19th century. A key background to this development was the Great Game – the strategic rivalry and conflict between the British Empire and the Russian Empire throughout Central Asia between 1830 and 1895. To counter Russian ambitions in the region and the potential threat it posed to the British position in India, the Indian Civil Service built up a system of surveillance, intelligence and counterintelligence. The existence of this shadowy conflict was popularized in Rudyard Kipling's famous spy book, Kim (1901), where he portrayed the Great Game (a phrase Kipling popularized) as an espionage and intelligence conflict that "never ceases, day or night".[2]

The establishment of dedicated intelligence and counterintelligence organizations had much to do with the colonial rivalries between the major European powers and to the accelerating development of military technology. As espionage became more widely used, it became imperative to expand the role of existing police and internal security forces into a role of detecting and countering foreign spies. The Evidenzbureau (founded in the Austrian Empire in 1850) had the role from the late-19th century of countering the actions of the Pan-Slavist movement operating out of Serbia.

After the fallout from the Dreyfus affair of 1894–1906 in France, responsibility for French military counter-espionage passed in 1899 to the Sûreté générale—an agency originally responsible for order enforcement and public safety—and overseen by the Ministry of the Interior.[3]

The Okhrana[4] initially formed in 1880 to combat political terrorism and left-wing revolutionary activity throughout the Russian Empire, was also tasked with countering enemy espionage.[5] Its main concern was the activities of revolutionaries, who often worked and plotted subversive actions from abroad. It set up a branch in Paris, run by Pyotr Rachkovsky, to monitor their activities. The agency used many methods to achieve its goals, including covert operations, undercover agents, and "perlustration"—the interception and reading of private correspondence. The Okhrana became notorious for its use of agents provocateurs, who often succeeded in penetrating the activities of revolutionary groups – including the Bolsheviks.[6]

Integrated counterintelligence agencies run directly by governments were also established. The British government founded the Secret Service Bureau in 1909 as the first independent and interdepartmental agency fully in control over all government counterintelligence activities.

Due to intense lobbying from William Melville and after he obtained German mobilization plans and proof of their financial support to the Boers, the British government authorized the formation of a new intelligence section in the War Office, MO3 (subsequently redesignated MO5) headed by Melville, in 1903. Working under-cover from a flat in London, Melville ran both counterintelligence and foreign intelligence operations, capitalizing on the knowledge and foreign contacts he had accumulated during his years running Special Branch.

Due to its success, the Government Committee on Intelligence, with support from Richard Haldane and Winston Churchill, established the Secret Service Bureau in 1909 as a joint initiative of the Admiralty, the War Office and the Foreign Office to control secret intelligence operations in the UK and overseas, particularly concentrating on the activities of the Imperial German government. Its first director was Captain Sir George Mansfield Smith-Cumming alias "C".[7] The Secret Service Bureau was split into a foreign and counter-intelligence domestic service in 1910. The latter, headed by Sir Vernon Kell, originally aimed at calming public fears of large-scale German espionage.[8] As the Service was not authorized with police powers, Kell liaised extensively with the Special Branch of Scotland Yard (headed by Basil Thomson), and succeeded in disrupting the work of Indian revolutionaries collaborating with the Germans during the war. Instead of a system whereby rival departments and military services would work on their own priorities with little to no consultation or cooperation with each other, the newly established Secret Intelligence Service was interdepartmental, and submitted its intelligence reports to all relevant government departments.[9] For the first time, governments had access to peacetime, centralized independent intelligence and counterintelligence bureaucracy with indexed registries and defined procedures, as opposed to the more ad hoc methods used previously.

In Soviet East Germany, counterespionage methods were targeted against civilians and referred to as decomposition methods. They were used to debilitate prominent individuals and groups for the purposes of stopping political dissent and culturally incorrect actions.[12] Decomposition methods became the main form of repression in East Germany from the early 1970's up until the collapse of the state in 1990.[13] They were also used in the Soviet Union more widely including as support for repeated acts of intellectual property theft.[14]

Categories

[edit]Collective counterintelligence is gaining information about an opponent's intelligence collection capabilities whose aim is at an entity.

Defensive counterintelligence is thwarting efforts by hostile intelligence services to penetrate the service.

Offensive counterintelligence is having identified an opponent's efforts against the system, trying to manipulate these attacks by either "turning" the opponent's agents into double agents or feeding them false information to report.[15]

Counterintelligence, counterterror, and government

[edit]Many governments organize counterintelligence agencies separately and distinct from their intelligence collection services. In most countries the counterintelligence mission is spread over multiple organizations, though one usually predominates. There is usually a domestic counterintelligence service, usually part of a larger law enforcement organization such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation in the United States.[16]

The United Kingdom has the separate Security Service, also known as MI5, which does not have direct police powers but works closely with law enforcement especially Special Branch that can carry out arrests, do searches with a warrant, etc.[17]

The Russian Federation's major domestic security organization is the FSB, which principally came from the Second Chief Directorate and Third Chief Directorate of the USSR's KGB.

Canada separates the functions of general defensive counterintelligence (contre-ingérence), security intelligence (the intelligence preparation necessary to conduct offensive counterintelligence), law enforcement intelligence, and offensive counterintelligence.

Military organizations have their own counterintelligence forces, capable of conducting protective operations both at home and when deployed abroad.[18] Depending on the country, there can be various mixtures of civilian and military in foreign operations. For example, while offensive counterintelligence is a mission of the US CIA's National Clandestine Service, defensive counterintelligence is a mission of the U.S. Diplomatic Security Service (DSS), Department of State, who work on protective security for personnel and information processed abroad at US Embassies and Consulates.[19]

The term counter-espionage is really specific to countering HUMINT, but, since virtually all offensive counterintelligence involves exploiting human sources, the term "offensive counterintelligence" is used here to avoid some ambiguous phrasing.

Other countries also deal with the proper organization of defenses against Foreign Intelligence Services (FIS), often with separate services with no common authority below the head of government.

France, for example, builds its domestic counterterror in a law enforcement framework. In France, a senior anti-terror magistrate is in charge of defense against terrorism. French magistrates have multiple functions that overlap US and UK functions of investigators, prosecutors, and judges. An anti-terror magistrate may call upon France's domestic intelligence service Direction générale de la sécurité intérieure (DGSI), which may work with the Direction générale de la sécurité extérieure (DGSE), foreign intelligence service.

Spain gives its Interior Ministry, with military support, the leadership in domestic counterterrorism. For international threats, the National Intelligence Center (CNI) has responsibility. CNI, which reports directly to the Prime Minister, is staffed principally by which is subordinated directly to the Prime Minister's office. After the March 11, 2004 Madrid train bombings, the national investigation found problems between the Interior Ministry and CNI, and, as a result, the National Anti-Terrorism Coordination Center was created. Spain's 3/11 Commission called for this center to do operational coordination as well as information collection and dissemination.[20] The military has organic counterintelligence to meet specific military needs.

Counterintelligence missions

[edit]Frank Wisner, a well-known CIA operations executive said of the autobiography of Director of Central Intelligence Allen W. Dulles,[21] that Dulles "disposes of the popular misconception that counterintelligence is essentially a negative and responsive activity, that it moves only or chiefly in reaction to situations thrust upon it and in counter to initiatives mounted by the opposition." Rather, he sees that it can be most effective, both in information gathering and protecting friendly intelligence services, when it creatively but vigorously attacks the "structure and personnel of hostile intelligence services."[22] Today's counterintelligence missions have broadened from the time when the threat was restricted to the foreign intelligence services (FIS) under the control of nation-states. Threats have broadened to include threats from non-national or trans-national groups, including internal insurgents, organized crime, and transnational based groups (often called "terrorists", but that is limiting). Still, the FIS term remains the usual way of referring to the threat against which counterintelligence protects.

In modern practice, several missions are associated with counterintelligence from the national to the field level.

- Defensive analysis is the practice of looking for vulnerabilities in one's own organization, and, with due regard for risk versus benefit, closing the discovered holes.

- Offensive counterespionage is the set of techniques that at least neutralizes discovered FIS personnel and arrests them or, in the case of diplomats, expels them by declaring them persona non grata. Beyond that minimum, it exploits FIS personnel to gain intelligence for one's own side, or actively manipulates the FIS personnel to damage the hostile FIS organization.

- Counterintelligence force protection source operations (CFSO) are human source operations, conducted abroad that are intended to fill the existing gap in national-level coverage in protecting a field station or force from terrorism and espionage.

Counterintelligence is part of intelligence cycle security, which, in turn, is part of intelligence cycle management. A variety of security disciplines also fall under intelligence security management and complement counterintelligence, including:

- Physical security

- Personnel security

- Communications security (COMSEC)

- Informations system security (INFOSEC)

- security classification

- Operations security (OPSEC)

The disciplines involved in "positive security," measures by which one's own society collects information on its actual or potential security, complement security. For example, when communications intelligence identifies a particular radio transmitter as one used only by a particular country, detecting that transmitter inside one's own country suggests the presence of a spy that counterintelligence should target. In particular, counterintelligence has a significant relationship with the collection discipline of HUMINT and at least some relationship with the others. Counterintelligence can both produce information and protect it.

All US departments and agencies with intelligence functions are responsible for their own security abroad, except those that fall under Chief of Mission authority.[23]

Governments try to protect three things:

- Their personnel

- Their installations

- Their operations

In many governments, the responsibility for protecting these things is split. Historically, the CIA assigned responsibility for protecting its personnel and operations to its Office of Security, while it assigned the security of operations to multiple groups within the Directorate of Operations: the counterintelligence staff and the area (or functional) unit, such as Soviet Russia Division. At one point, the counterintelligence unit operated quite autonomously, under the direction of James Jesus Angleton. Later, operational divisions had subordinate counterintelligence branches, as well as a smaller central counterintelligence staff. Aldrich Ames was in the Counterintelligence Branch of Europe Division, where he was responsible for directing the analysis of Soviet intelligence operations. US military services have had a similar and even more complex split.

This kind of division clearly requires close coordination, and this in fact occurs on a daily basis. The interdependence of the US counterintelligence community is also manifest in its relationships with liaison services. The counterintelligence community cannot cut off these relationships because of concern about security, but experience has shown that it must calculate the risks involved.[23]

On the other side of the CI coin, counterespionage has one purpose that transcends all others in importance: penetration. The emphasis which the KGB places on penetration is evident in the cases already discussed from the defensive or security viewpoint. The best security system in the world cannot provide an adequate defense against it because the technique involves people. The only way to be sure that an enemy has been contained is to know his plans in advance and in detail.

Moreover, only a high-level penetration of the opposition can tell you whether your own service is penetrated. A high-level defector can also do this, but the adversary knows that he defected and within limits can take remedial action. Conducting CE without the aid of penetrations is like fighting in the dark. Conducting CE with penetrations can be like shooting fish in a barrel.[23]

In the British service, the cases of the Cambridge Five, and the later suspicions about MI5 chief Sir Roger Hollis caused great internal dissension. Clearly, the British were penetrated by Philby, but it has never been determined, in any public forum, if there were other serious penetrations. In the US service, there was also significant disruption over the contradictory accusations about moles from defectors Anatoliy Golitsyn and Yuri Nosenko, and their respective supporters in CIA and the British Security Service (MI5). Golitsyn was generally believed by Angleton. George Kisevalter, the CIA operations officer that was the CIA side of the joint US-UK handling of Oleg Penkovsky, did not believe Angleton's theory that Nosenko was a KGB plant. Nosenko had exposed John Vassall, a KGB asset principally in the British Admiralty, but there were arguments Vassall was a KGB sacrifice to protect other operations, including Nosenko and a possibly more valuable source on the Royal Navy.

Defensive counterintelligence

[edit]Defensive counterintelligence starts by looking for places in one's own organization that could easily be exploited by foreign intelligence services (FIS). FIS is an established term of art in the counterintelligence community, and, in today's world, "foreign" is shorthand for "opposing." Opposition might indeed be a country, but it could be a transnational group or an internal insurgent group. Operations against a FIS might be against one's own nation, or another friendly nation. The range of actions that might be done to support a friendly government can include a wide range of functions, certainly including military or counterintelligence activities, but also humanitarian aid and aid to development ("nation building").[24]

Terminology here is still emerging, and "transnational group" could include not only terrorist groups but also transnational criminal organization. Transnational criminal organizations include the drug trade, money laundering, extortion targeted against computer or communications systems, smuggling, etc.

"Insurgent" could be a group opposing a recognized government by criminal or military means, as well as conducting clandestine intelligence and covert operations against the government in question, which could be one's own or a friendly one.

Counterintelligence and counterterrorism analyses provide strategic assessments of foreign intelligence and terrorist groups and prepare tactical options for ongoing operations and investigations. Counterespionage may involve proactive acts against foreign intelligence services, such as double agents, deception, or recruiting foreign intelligence officers. While clandestine HUMINT sources can give the greatest insight into the adversary's thinking, they may also be most vulnerable to the adversary's attacks on one's own organization. Before trusting an enemy agent, remember that such people started out as being trusted by their own countries and may still be loyal to that country.

Offensive counterintelligence operations

[edit]Wisner emphasized his own, and Dulles', views that the best defense against foreign attacks on, or infiltration of, intelligence services is active measures against those hostile services.[22] This is often called counterespionage: measures taken to detect enemy espionage or physical attacks against friendly intelligence services, prevent damage and information loss, and, where possible, to turn the attempt back against its originator. Counterespionage goes beyond being reactive and actively tries to subvert hostile intelligence service, by recruiting agents in the foreign service, by discrediting personnel actually loyal to their own service, and taking away resources that would be useful to the hostile service. All of these actions apply to non-national threats as well as to national organizations.

If the hostile action is in one's own country or in a friendly one with co-operating police, the hostile agents may be arrested, or, if diplomats, declared persona non grata. From the perspective of one's own intelligence service, exploiting the situation to the advantage of one's side is usually preferable to arrest or actions that might result in the death of the threat. The intelligence priority sometimes comes into conflict with the instincts of one's own law enforcement organizations, especially when the foreign threat combines foreign personnel with citizens of one's country.

In some circumstances, arrest may be a first step in which the prisoner is given the choice of co-operating or facing severe consequence up to and including a death sentence for espionage. Co-operation may consist of telling all one knows about the other service but preferably actively assisting in deceptive actions against the hostile service.

Counterintelligence protection of intelligence services

[edit]Defensive counterintelligence specifically for intelligence services involves risk assessment of their culture, sources, methods and resources. Risk management must constantly reflect those assessments, since effective intelligence operations are often risk-taking. Even while taking calculated risks, the services need to mitigate risk with appropriate countermeasures.

FIS are especially able to explore open societies and, in that environment, have been able to subvert insiders in the intelligence community. Offensive counterespionage is the most powerful tool for finding penetrators and neutralizing them, but it is not the only tool. Understanding what leads individuals to turn on their own side is the focus of Project Slammer. Without undue violations of personal privacy, systems can be developed to spot anomalous behavior, especially in the use of information systems.

Decision makers require intelligence free from hostile control or manipulation. Since every intelligence discipline is subject to manipulation by our adversaries, validating the reliability of intelligence from all collection platforms is essential. Accordingly, each counterintelligence organization will validate the reliability of sources and methods that relate to the counterintelligence mission in accordance with common standards. For other mission areas, the USIC will examine collection, analysis, dissemination practices, and other intelligence activities and will recommend improvements, best practices, and common standards.[25]

Intelligence is vulnerable not only to external but also to internal threats. Subversion, treason, and leaks expose vulnerabilities, governmental and commercial secrets, and intelligence sources and methods. The insider threat has been a source of extraordinary damage to US national security, as with Aldrich Ames, Robert Hanssen, and Edward Lee Howard, all of whom had access to major clandestine activities. Had an electronic system to detect anomalies in browsing through counterintelligence files been in place, Robert Hanssen's searches for suspicion of activities of his Soviet (and later Russian) paymasters might have surfaced early. Anomalies might simply show that an especially-creative analyst has a trained intuition possible connections and is trying to research them.

Adding the new tools and techniques to [national arsenals], the counterintelligence community will seek to manipulate foreign spies, conduct aggressive investigations, make arrests and, where foreign officials are involved, expel them for engaging in practices inconsistent with their diplomatic status or exploit them as an unwitting channel for deception, or turn them into witting double agents.[25] "Witting" is a term of intelligence art that indicates that one is not only aware of a fact or piece of information but also aware of its connection to intelligence activities.

Victor Suvorov, the pseudonym of a former Soviet military intelligence (GRU) officer, makes the point that a defecting HUMINT officer is a special threat to walk-in or other volunteer assets of the country that he is leaving. Volunteers who are "warmly welcomed" do not take into consideration the fact that they are despised by hostile intelligence agents.

The Soviet operational officer, having seen a great deal of the ugly face of communism, very frequently feels the utmost repulsion to those who sell themselves to it willingly. And when a GRU or KGB officer decides to break with his criminal organization, something which fortunately happens quite often, the first thing he will do is try to expose the hated volunteer.[26]

Counterintelligence force protection source operations

[edit]Attacks against military, diplomatic, and related facilities are a very real threat, as demonstrated by the 1983 attacks against French and US peacekeepers in Beirut, the 1996 attack on the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, 1998 attacks on Colombian bases and on U.S. embassies (and local buildings) in Kenya and Tanzania the 2000 attack on the USS Cole, and many others. The U.S. military force protection measures are the set of actions taken against military personnel and family members, resources, facilities and critical information, and most countries have a similar doctrine for protecting those facilities and conserving the potential of the forces. Force protection is defined to be a defense against deliberate attack, not accidents or natural disasters.

Counterintelligence Force Protection Source Operations (CFSO) are human source operations, normally clandestine in nature, conducted abroad that are intended to fill the existing gap in national level coverage, as well as satisfying the combatant commander's intelligence requirements.[27] Military police and other patrols that mingle with local people may indeed be valuable HUMINT sources for counterintelligence awareness, but are not themselves likely to be CFSOs. Gleghorn distinguishes between the protection of national intelligence services, and the intelligence needed to provide combatant commands with the information they need for force protection. There are other HUMINT sources, such as military reconnaissance patrols that avoid mixing with foreign personnel, that indeed may provide HUMINT, but not HUMINT especially relevant to counterintelligence.[28] Active countermeasures, whether for force protection, protection of intelligence services, or protection of national security interests, are apt to involve HUMINT disciplines, for the purpose of detecting FIS agents, involving screening and debriefing of non-tasked human sources, also called casual or incidental sources. such as:

- walk-ins and write-ins (individuals who volunteer information)

- unwitting sources (any individual providing useful information to counterintelligence, who in the process of divulging such information may not know they are aiding an investigation)

- defectors and enemy prisoners of war (EPW)

- refugee populations and expatriates

- interviewees (individuals contacted in the course of an investigation)

- official liaison sources.

Physical security is important, but it does not override the role of force protection intelligence... Although all intelligence disciplines can be used to gather force protection intelligence, HUMINT collected by intelligence and CI agencies plays a key role in providing indications and warning of terrorist and other force protection threats.[29]

Force protection, for forces deployed in host countries, occupation duty, and even at home, may not be supported sufficiently by a national-level counterterrorism organization alone. In a country, colocating FPCI personnel, of all services, with military assistance and advisory units, allows agents to build relationships with host nation law enforcement and intelligence agencies, get to know the local environments, and improve their language skills. FPCI needs a legal domestic capability to deal with domestic terrorism threats.

As an example of terrorist planning cycles, the Khobar Towers attack shows the need for long-term FPCI. "The Hizballah operatives believed to have conducted this attack began intelligence collection and planning activities in 1993. They recognized American military personnel were billeted at Khobar Towers in the fall of 1994 and began surveillance of the facility, and continued to plan, in June 1995. In March 1996, Saudi Arabian border guards arrested a Hizballah member attempting plastic explosive into the country, leading to the arrest of two more Hizballah members. Hizballah leaders recruited replacements for those arrested, and continued planning for the attack."[30]

Defensive counterintelligence operations

[edit]In U.S. doctrine, although not necessarily that of other countries, CI is now seen as primarily a counter to FIS HUMINT. In the 1995 US Army counterintelligence manual, CI had a broader scope against the various intelligence collection disciplines. Some of the overarching CI tasks are described as

- Developing, maintaining, and disseminating multidiscipline threat data and intelligence files on organizations, locations, and individuals of CI interest. This includes insurgent and terrorist infrastructure and individuals who can assist in the CI mission.

- Educating personnel in all fields of security. A component of this is the multidiscipline threat briefing. Briefings can and should be tailored, both in scope and classification level. Briefings could then be used to familiarize supported commands with the nature of the multidiscipline threat posed against the command or activity.

More recent US joint intelligence doctrine[31] restricts its primary scope to counter-HUMINT, which usually includes counter-terror. It is not always clear, under this doctrine, who is responsible for all intelligence collection threats against a military or other resource. The full scope of US military counterintelligence doctrine has been moved to a classified publication, Joint Publication (JP) 2-01.2, Counterintelligence and Human Intelligence Support to Joint Operations.

More specific countermeasures against intelligence collection disciplines are listed below

| Discipline | Offensive CI | Defensive CI |

|---|---|---|

| HUMINT | Counterreconnaissance, offensive counterespionage | Deception in operations security |

| SIGINT | Recommendations for kinetic and electronic attack | Radio OPSEC, use of secure telephones, SIGSEC, deception |

| IMINT | Recommendations for kinetic and electronic attack | Deception, OPSEC countermeasures, deception (decoys, camouflage)

If accessible, use SATRAN reports of satellites overhead to hide or stop activities while being viewed |

Counter-HUMINT

[edit]Counter-HUMINT deals with both the detection of hostile HUMINT sources within an organization, or the detection of individuals likely to become hostile HUMINT sources, as a mole or double agent. There is an additional category relevant to the broad spectrum of counterintelligence: why one becomes a terrorist. [citation needed]

The acronym MICE:

- Money

- Ideology

- Compromise (or coercion)

- Ego

describes the most common reasons people break trust and disclose classified materials, reveal operations to hostile services, or join terrorist groups. It makes sense, therefore, to monitor trusted personnel for risks in these areas, such as financial stress, extreme political views, potential vulnerabilities for blackmail, and excessive need for approval or intolerance of criticism. With luck, problems in an employee can be caught early, assistance can be provided to correct them, and not only is espionage avoided, but a useful employee retained.

Sometimes, the preventive and neutralization tasks overlap, as in the case of Earl Edwin Pitts. Pitts had been an FBI agent who had sold secret information to the Soviets, and, after the fall of the USSR, to the Russians. He was caught by an FBI false flag sting, in which FBI agents, posing as Russian FSB agents, came to Pitts with an offer to "reactivate" him. His activities seemed motivated by both money and ego over perceived bad treatment when he was an FBI agent. His sentence required him to tell the FBI all he knew of foreign agents. Ironically, he told them of suspicious actions by Robert Hanssen, which were not taken seriously at the time.

Motivations for information and operations disclosure

[edit]To go beyond slogans, Project Slammer was an effort of the Intelligence Community Staff, under the Director of Central Intelligence, to come up with characteristics of an individual likely to commit espionage against the United States. It "examines espionage by interviewing and psychologically assessing actual espionage subjects. Additionally, persons knowledgeable of subjects are contacted to better understand the subjects' private lives and how they are perceived by others while conducting espionage."[32]

| Attitude | Manifestations |

|---|---|

| Basic belief structure | – Special, even unique.

– Deserving. – The individual's situation is not satisfactory. – No other (easier) option (than to engage in espionage). – Doing only what others frequently do. – Not a bad person. – Performance in a government job (if presently employed) is separate from espionage; espionage does not (really) discount contribution in the workplace. – Security procedures do not (really) apply to the individual. – Security programs (e.g., briefings) have no meaning for the individual unless they connect with something with which they can personally identify. |

| Feels isolated from the consequences of his actions: | – The individual sees their situation in a context in which they face continually narrowing options until espionage seems reasonable. The process that evolves into espionage reduces barriers, making it essentially "Okay" to initiate the crime.

– They see espionage as a "Victimless" crime. – Once they consider espionage, they figure out how it might be done. These are mutually reinforcing, often simultaneous events. – Subject finds that it is easy to go around security safeguards (or is able to solve that problem). They belittle the security system, feeling that if the information was really important espionage would be hard to do (the information would really be better protected). This "Ease of accomplishment" further reinforces resolve. |

| Attempts to cope with espionage activity | – Anxious on initial hostile intelligence service contact (some also feel thrill and excitement).

– After a relationship with espionage activity and HOIS develops, the process becomes much more bearable, espionage continues (even flourishes). – In the course of long-term activity, subjects may reconsider their involvement. – Some consider breaking their role to become an operative for the government. This occurs when access to classified information is lost or there is a perceived need to prove themselves or both. – Others find that espionage activity becomes stressful, they no longer want it. Glamour (if present earlier) subsides. They are reluctant to continue. They may even break contact. – Sometimes they consider telling authorities what they have done. Those wanting to reverse their role aren't confessing, they're negotiating. Those who are "Stressed out" want to confess. Neither wants punishment. Both attempt to minimize or avoid punishment. |

According to a press report about Project Slammer and Congressional oversight of counterespionage, one fairly basic function is observing one's own personnel for behavior that either suggests that they could be targets for foreign HUMINT, or may already have been subverted. News reports indicate that in hindsight, red flags were flying but not noticed.[33] In several major penetrations of US services, such as Aldrich Ames, the Walker ring or Robert Hanssen, the individual showed patterns of spending inconsistent with their salary. Some people with changed spending may have a perfectly good reason, such as an inheritance or even winning the lottery, but such patterns should not be ignored.

Personnel in sensitive positions, who have difficulty getting along with peers, may become risks for being compromised with an approach based on ego. William Kampiles, a low-level worker in the CIA Watch Center, sold, for a small sum, the critical operations manual on the KH-11 reconnaissance satellite. To an interviewer, Kampiles suggested that if someone had noted his "problem"—constant conflicts with supervisors and co-workers—and brought in outside counseling, he might not have stolen the KH-11 manual.[33]

By 1997, the Project Slammer work was being presented at public meetings of the Security Policy Advisory Board.[34] While a funding cut caused the loss of impetus in the mid-nineties, there are research data used throughout the security community. They emphasize the

essential and multi-faceted motivational patterns underlying espionage. Future Slammer analyses will focus on newly developing issues in espionage such as the role of money, the new dimensions of loyalty and what seems to be a developing trend toward economic espionage.

Counter-SIGINT (Signals Intelligence)

[edit]Military and security organizations will provide secure communications, and may monitor less secure systems, such as commercial telephones or general Internet connections, to detect inappropriate information being passed through them. Education on the need to use secure communications, and instruction on using them properly so that they do not become vulnerable to specialized technical interception.

Counter-IMINT (Imagery Intelligence)

[edit]The basic methods of countering IMINT are to know when the opponent will use imaging against one's own side, and interfering with the taking of images. In some situations, especially in free societies, it must be accepted that public buildings may always be subject to photography or other techniques.

Countermeasures include putting visual shielding over sensitive targets or camouflaging them. When countering such threats as imaging satellites, awareness of the orbits can guide security personnel to stop an activity, or perhaps cover the sensitive parts, when the satellite is overhead. This also applies to imaging on aircraft and UAVs, although the more direct expedient of shooting them down, or attacking their launch and support area, is an option in wartime.

Counter-OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence)

[edit]While the concept well precedes the recognition of a discipline of OSINT, the idea of censorship of material directly relevant to national security is a basic OSINT defense. In democratic societies, even in wartime, censorship must be watched carefully lest it violate reasonable freedom of the press, but the balance is set differently in different countries and at different times.

The United Kingdom is generally considered to have a very free press, but there is the DA-Notice, formerly D-notice system. Many British journalists find that the system is used fairly, but there will always be arguments. In the specific context of counterintelligence, note that Peter Wright, a former senior member of the Security Service who left their service without his pension, moved to Australia before publishing his book Spycatcher. While much of the book was reasonable commentary, it revealed some specific and sensitive techniques, such as Operation RAFTER, a means of detecting the existence and setting of radio receivers.

Counter-MASINT (Measurement and Signature Intelligence)

[edit]MASINT is mentioned here for completeness, but the discipline contains so varied a range of technologies that a type-by-type strategy is beyond the current scope. One example, however, can draw on the Operation RAFTER technique revealed in Wright's book. With the knowledge that Radiofrequency MASINT was being used to pick up an internal frequency in radio receivers, it would be possible to design a shielded receiver that would not radiate the signal that RAFTER monitored.

Theory of offensive counterintelligence

[edit]The phrase offensive counterintelligence is ordinarily considered as being synonymous in meaning with the term counterespionage. The US Department of Defense defines it as 'That aspect of counterintelligence designed to detect, destroy, neutralize, exploit, or prevent espionage activities through identification, penetration, manipulation, deception, and repression of individuals, groups, or organizations conducting or suspected of conducting espionage activities.[35] At the heart of exploitation operations is the objective to degrade the effectiveness of an adversary's intelligence service or a terrorist organization. Offensive counterespionage (and counterterrorism) is done one of two ways: either by manipulating the adversary (FIS or terrorist) in some manner or by disrupting the adversary's normal operations.

Defensive counterintelligence operations that succeed in breaking up a clandestine network by arresting the persons involved or by exposing their actions demonstrate that disruption is quite measurable and effective against FIS if the right actions are taken. If defensive counterintelligence stops terrorist attacks, it has succeeded.

Offensive counterintelligence seeks to damage the long-term capability of the adversary. If it can lead a national adversary into putting large resources into protecting from a nonexistent threat, or if it can lead terrorists to assume that all of their "sleeper" agents in a country have become unreliable and must be replaced (and possibly killed as security risks), there is a greater level of success than can be seen from defensive operations alone, To carry out offensive counterintelligence, however, the service must do more than detect; it must manipulate persons associated with the adversary.

The Canadian Department of National Defence makes some useful logical distinctions in its Directive on its[36] National Counter-Intelligence Unit. The terminology is not the same as used by other services, but the distinctions are useful:

- "Counter-intelligence (contre-ingérence) means activities concerned with identifying and counteracting threats to the security of DND employees, CF members, and DND and CF property and information, that are posed by hostile intelligence services, organizations or individuals, who are or may be engaged in espionage, sabotage, subversion, terrorist activities, organized crime or other criminal activities." This corresponds to defensive counterintelligence in other services.

- "Security intelligence (renseignement de sécurité) means intelligence on the identity, capabilities and intentions of hostile intelligence services, organizations or individuals, who are or may be engaged in espionage, sabotage, subversion, terrorist activities, organized crime or other criminal activities." This does not (emphasis added) correspond directly to offensive counterintelligence, but is the intelligence preparation necessary to conduct offensive counterintelligence.

- The duties of the Canadian Forces National Counter-Intelligence Unit include "identifying, investigating and countering threats to the security of the DND and the CF from espionage, sabotage, subversion, terrorist activities, and other criminal activity; identifying, investigating and countering the actual or possible compromise of highly classified or special DND or CF material; conducting CI security investigations, operations and security briefings and debriefings to counter threats to, or to preserve, the security of DND and CF interests." This mandate is a good statement of a mandate to conduct offensive counterintelligence.

DND further makes the useful clarification,[37] "The security intelligence process should not be confused with the liaison conducted by members of the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service (CFNIS) for the purpose of obtaining criminal intelligence, as the collection of this type of information is within their mandate."

Manipulating an intelligence professional, himself trained in counterintelligence, is no easy task, unless he is already predisposed toward the opposing side. Any effort that does not start with a sympathetic person will take a long-term commitment, and creative thinking to overcome the defenses of someone who knows he is a counterintelligence target and also knows counterintelligence techniques.

Terrorists on the other hand, although they engage in deception as a function of security appear to be more prone to manipulation or deception by a well-placed adversary than are foreign intelligence services. This is in part due to the fact that many terrorist groups, whose members "often mistrust and fight among each other, disagree, and vary in conviction.", are not as internally cohesive as foreign intelligence services, potentially leaving them more vulnerable to both deception and manipulation.

Further reading

[edit]- Riehle, Kevin (2025). Counterintelligence at its Core: Assessing and Preventing Foreign Espionage. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 978-1-962551-48-9.

- Johnson, William (2009). Thwarting Enemies at Home and Abroad: How to Be a Counterintelligence Officer. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-1-589-01255-4.

- Ginkel, B. van (2012). "Towards the intelligent use of intelligence: Quis Custodiet ipsos Custodes?". Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism Studies. 3 (10). The Hague: The International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. doi:10.19165/2012.1.10 (inactive 1 July 2025). Archived from the original on 2022-12-03. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - Lee, Newton (2015). Counterterrorism and Cybersecurity: Total Information Awareness (Second ed.). Springer International Publishing Switzerland. ISBN 978-3319172439.

- Selby, Scott Andrew. The Axmann Conspiracy: The Nazi Plan for a Fourth Reich and How the U.S. Army Defeated It. Berkley (Penguin), Sept. 2012. ISBN 0-425-25270-1

- Toward a Theory of CI

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, William (2009). Thwarting Enemies at Home and Abroad: How to be a Counterintelligence Officer. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Philip H.J. Davies (2012). Intelligence and Government in Britain and the United States: A Comparative Perspective. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440802812.

- ^ Anciens des Services Spéciaux de la Défense Nationale Archived 2016-03-15 at the Wayback Machine ( France )

- ^ "Okhrana" literally means "the guard"

- ^ Okhrana Britannica Online

- ^ Ian D. Thatcher, Late Imperial Russia: problems and prospects, page 50.

- ^ "SIS Or MI6. What's in a Name?". SIS website. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ Christopher Andrew, The Defence of the Realm: The Authorized History of Mi5 (London, 2009), p.21.

- ^ Calder Walton (2013). Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War, and the Twilight of Empire. Overlook. pp. 5–6. ISBN 9781468310436.

- ^ Schmeidel, John Christian (2008). "Origins and developments of the East German secret police: Disruptions and breakouts". Stasi: Sword and Shield of the Party. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-01841-5.

- ^ Guriev, Sergei; Treisman, Daniel (4 April 2023). Spin Dictators: The Changing Face of Tyranny in the 21st Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-0691224473.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schmeidel, John Christian (2008). "Origins and developments of the East German secret police: Disruptions and breakouts". Stasi: Sword and Shield of the Party. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-01841-5.

- ^ Dennis, Mike (2003). "Tackling the enemy: quiet repression and preventive decomposition". The Stasi: Myth and Reality. Pearson Education Limited. p. 112. ISBN 0582414229.

- ^ Ellis, Frank (1999). "Information Deficit". From Glasnost to the Internet: Russia's New Infosphere. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillain. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-349-27078-1.

- ^ Lowenthal, M. (2003). Intelligence: From secrets to policy. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- ^ "Counterintelligence". FBI. Archived from the original on 2016-07-17.

- ^ "COUNTER-ESPIONAGE". Security Service MI5. Archived from the original on 2020-01-15.

- ^ Clark, R.M. and Mitchell, W.L., 2018. Deception: Counterdeception and Counterintelligence. CQ Press.

- ^ "Counterintelligence Investigations". Retrieved 2008-05-08.

- ^ Archick, Kristen (2006-07-24). "European Approaches to Homeland Security and Counterterrorism" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Dulles, Allen W. (1977). The Craft of Intelligence. Greenwood. ISBN 0-8371-9452-0. Dulles-1977.

- ^ a b Wisner, Frank G. (1993-09-22). "On "The Craft of Intelligence"". CIA-Wisner-1993. Archived from the original on 2007-11-15. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ a b c Matschulat, Austin B. (1996-07-02). "Coordination and Cooperation in Counerintelligence". Archived from the original on 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ "Joint Publication 3-07.1: Joint Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Foreign Internal Defense (FID)" (PDF). 2004-04-30. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ a b "National Counterintelligence Executive (NCIX)" (PDF). 2007.

- ^ Suvorov, Victor (1984). "Chapter 4, Agent Recruiting". Inside Soviet Military Intelligence. MacMillan Publishing Company.

- ^ a b US Department of the Army (1995-10-03). "Field Manual 34–60: Counterintelligence". Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ Gleghorn, Todd E. (September 2003). "Exposing the Seams: the Impetus for Reforming US Counterintelligence" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ US Department of Defense (2007-07-12). "Joint Publication 1-02 Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ Imbus, Michael T (April 2002). "Identifying Threats: Improving Intelligence and Counterintelligence Support to Force Protection" (PDF). USAFCSC-Imbus-2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 2, 2004. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ Joint Chiefs of Staff (2007-06-22). "Joint Publication 2-0: Intelligence" (PDF). US JP 2-0. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Intelligence Community Staff (12 April 1990). "Project Slammer Interim Progress Report". Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b Stein, Jeff (July 5, 1994). "The Mole's Manual". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ "Security Policy Advisory Board Meeting: Draft Minutes". Federation of American Scientists. 12 December 1997. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ "Counterintelligence" (PDF). Marines. US Marine Corps. Retrieved 22 March 2025.

- ^ "Canadian Forces National Counter-Intelligence Unit". 2003-03-28. Canada-DND-DAOD 8002-2. Archived from the original on 2007-11-21. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ "Security Intelligence Liaison Program". 2003-03-28. Canada-DND-DAOD 8002-3. Archived from the original on 2007-11-30. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

External links

[edit]Counterintelligence

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Core Principles

Fundamental Concepts and Objectives

Counterintelligence encompasses the collection of information and execution of activities designed to identify, assess, deceive, exploit, disrupt, or protect against espionage, other intelligence activities, sabotage, or assassinations conducted by or on behalf of foreign powers, organizations, or persons.[10] This dual nature—encompassing both informational products and operational actions—distinguishes it as a proactive discipline aimed at countering adversarial intelligence efforts that seek to undermine national security or economic interests.[11] At its core, counterintelligence operates on the principle of information denial and asymmetry, where the primary causal mechanism is the prevention of unauthorized access to sensitive data while simultaneously degrading an adversary's ability to gather or utilize such data effectively.[9] The fundamental objectives of counterintelligence include safeguarding classified information and critical assets, such as advanced technologies and research, from foreign exploitation.[3] Defensive efforts focus on detection and neutralization of threats, including insider risks and cyber intrusions, through measures like personnel vetting, secure handling protocols, and anomaly reporting.[9] Offensive objectives extend to misleading adversaries, concealing penetrations, and manipulating their operations to waste resources or expose their networks, thereby turning adversarial intelligence activities against themselves.[11] These goals are pursued across government, military, and private sectors, with empirical success measured by metrics such as thwarted espionage cases— for instance, the FBI reported over 1,000 counterintelligence investigations active as of 2023, targeting threats from nations like China and Russia.[3] Key concepts include the identification of foreign intelligence threats via indicators like unusual contacts or data exfiltration attempts, followed by exploitation through techniques such as double-agent operations or disinformation feeds.[9] Counterintelligence relies on interdisciplinary integration, combining human, signals, and technical intelligence to achieve causal disruption of enemy cycles of collection and analysis.[12] Unlike passive security, it emphasizes active countermeasures, recognizing that unaddressed intelligence vulnerabilities can lead to cascading failures, as evidenced by historical breaches like the 2010 exposure of U.S. sources to Russia due to undetected moles.[12] Ultimately, effective counterintelligence maintains a state's operational secrecy and strategic edge by systematically eroding adversaries' informational advantages.[3]First-Principles Approach to Counterintelligence

Counterintelligence fundamentally addresses the imperative to deny adversaries the informational asymmetries that enable hostile actions, rooted in the competitive dynamics of state and non-state actors seeking dominance through clandestine collection and subversion. In environments where secrecy underpins strategic advantages, vulnerabilities arise from human, technical, and systemic weaknesses that adversaries exploit to gather intelligence, conduct sabotage, or influence decisions. The core objective is thus to detect, disrupt, and deter these threats at their inception, preserving the integrity of one's own intelligence apparatus and critical assets. This derives from the causal chain wherein undetected espionage leads to compromised operations, eroded trust in personnel, and cascading failures in national security, as evidenced by historical penetrations like the Cambridge Five network, which supplied Soviet intelligence with British atomic secrets from the 1940s through the early 1950s.[12] At its essence, a first-principles framework prioritizes protection through denial and deception, assuming adversaries operate with intent to infiltrate via agents, cyber means, or elicited insiders. Defensive counterintelligence employs compartmentalization, need-to-know access restrictions, and anomaly detection to minimize exposure, as articulated in U.S. doctrine emphasizing the safeguarding of classified information against foreign powers.[11] Offensive countermeasures, conversely, involve proactive penetration of enemy services to identify and neutralize threats, with doctrines asserting that "the key to counterintelligence success is penetration" through recruitment of opposition officers or exploitation of double agents.[5] Empirical validation comes from operations like the FBI's counterespionage against Soviet moles during the Cold War, where vetting and surveillance thwarted infiltrations, preventing losses estimated in billions of dollars in technology and military capabilities.[3] This approach demands integration across all phases of activity, rejecting siloed or reactive postures in favor of pervasive vigilance. Core tenets include assuming betrayal as a baseline risk—given that "for every American spy, there are several members of the opposition service who know who he or she is"—and embedding counterintelligence in human intelligence operations to target adversary handlers systematically.[13] Rigorous personnel screening, such as polygraph examinations and background investigations mandated under U.S. Executive Order 12333 since 1981, forms the foundational barrier, while technical safeguards like secure communications protocols counter signals intelligence threats. Failure to adhere invites systemic compromise, as seen in the 2010 discovery of Chinese espionage networks penetrating U.S. defense contractors, compromising F-35 fighter jet designs and costing over $100 billion in remedial efforts.[14] Ultimately, counterintelligence succeeds by aligning with causal realism: threats persist until actively broken, requiring sustained resource allocation to outpace adaptive adversaries.Distinctions from Related Fields

Counterintelligence differs fundamentally from positive or foreign intelligence activities, which primarily involve the collection and analysis of information on adversaries to inform decision-making. Whereas foreign intelligence seeks to penetrate and understand enemy capabilities, intentions, and activities through methods such as human sources or signals interception, counterintelligence focuses on identifying, disrupting, and neutralizing the enemy's own intelligence-gathering efforts directed against one's own side.[15][16] This protective orientation means counterintelligence operations often prioritize deception, denial, and exploitation over mere observation, aiming to render adversarial intelligence ineffective rather than to exploit it for offensive gains.[17] In contrast to general security measures, which encompass a wide array of protective actions including physical barriers, access controls, and cybersecurity protocols to safeguard assets broadly, counterintelligence specifically targets threats posed by foreign intelligence entities, such as espionage, sabotage, or subversion. Security functions may overlap with counterintelligence in areas like vetting personnel or securing facilities, but they lack the specialized focus on countering clandestine human operations, double-agent handling, or disinformation campaigns orchestrated by state adversaries.[3][18] For instance, while a security clearance process verifies an individual's background to prevent unauthorized disclosure, counterintelligence investigations delve into potential recruitment by foreign services, assessing loyalty under adversarial influence.[19] Counterespionage represents a core subset of counterintelligence but is narrower in scope, concentrating on the detection, apprehension, and prosecution of spies and agents engaged in espionage. Broader counterintelligence extends beyond individual traitor-hunting to include proactive measures like feeding false information to mislead enemies (misinformation operations) or conducting offensive actions to dismantle foreign intelligence networks entirely.[20] This distinction arises because espionage detection addresses immediate penetrations, whereas full-spectrum counterintelligence anticipates and preempts a range of intelligence threats, including non-human elements like cyber intrusions attributed to state actors.[16]Historical Development

Origins and Early Practices

Counterintelligence practices emerged in ancient civilizations as rulers sought to protect against espionage and internal threats. In ancient Egypt, pharaohs employed agents to detect disloyal subjects and monitor potential foreign infiltrators, forming early security protocols that laid groundwork for organized counterespionage.[21] Similarly, security services in Assyria, Persia, and other Near Eastern states focused on rapid information control to neutralize spies and saboteurs, emphasizing vigilance over state secrets.[22] These rudimentary efforts relied on informants, physical surveillance, and punitive measures rather than formalized structures. In classical China, Sun Tzu's The Art of War (circa 5th century BCE) articulated foundational principles for countering enemy intelligence, advocating the use of converted spies—enemy agents turned double agents—and disinformation to mislead adversaries while safeguarding one's own operations.[23] This text underscored the causal link between undetected espionage and military defeat, promoting proactive deception and source protection as core tactics. In Europe, during the 16th century, Sir Francis Walsingham, principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I, established one of the earliest systematic counterintelligence networks in England. Walsingham's operations countered Catholic plots and Spanish threats through domestic surveillance, foreign agent recruitment, and cryptographic analysis of intercepted correspondence, such as deciphering the Babington Plot letters in 1586 that thwarted an assassination attempt.[24] His methods integrated human intelligence with technical means, setting precedents for state-level defensive operations. By the 19th century, nation-state formation spurred dedicated counterintelligence entities amid imperial rivalries. The Russian Okhrana, founded in 1881 following Tsar Alexander II's assassination, functioned as a secret police force specializing in surveillance, informant networks, and neutralization of revolutionary and foreign espionage activities, including operations abroad like in Paris to track émigré dissidents.[25] Concurrently, the "Great Game"—the Anglo-Russian contest for Central Asian influence from the early 1800s to 1907—involved mutual counterespionage, with both empires deploying agents to map territories, recruit locals, and disrupt rival intelligence gathering through betrayal and misinformation.[26] These practices highlighted the shift toward offensive countermeasures, such as false flag operations and agent handling, driven by geopolitical competition rather than solely internal security.World War II and Cold War Eras

During World War II, counterintelligence operations expanded significantly as nations sought to neutralize enemy espionage amid total war. Britain's MI5 implemented the Double-Cross System starting in May 1940, systematically capturing nearly all German agents landing in the United Kingdom and converting over 20 into double agents who fed disinformation to the Abwehr, thereby safeguarding Allied secrets and enabling strategic deceptions such as Operation Fortitude, which misled German forces about the Normandy invasion site in June 1944.[27][28] In the United States, the Army's Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), formalized on January 31, 1942, from the earlier Corps of Intelligence Police, deployed over 7,600 agents by war's end to detect sabotage, screen personnel, and counter Axis spies across theaters, including the apprehension of 312 suspected agents in the European Theater alone between 1942 and 1945.[29][30] The Soviet Union established SMERSH (an acronym for "Death to Spies") on April 19, 1943, as a military counterintelligence directorate under direct People's Commissariat of Defense control, with Viktor Abakumov as its head; it operated up to 45 directorates across fronts and armies, claiming to neutralize over 30,000 German spies and collaborators but also executing or imprisoning hundreds of thousands of Red Army personnel on suspicion of treason, often without due process, reflecting Stalin's emphasis on internal loyalty over evidentiary standards.[31][32] The Office of Strategic Services (OSS), America's wartime intelligence precursor, ran limited double-agent networks in Europe, identifying Abwehr operations and supporting deception efforts, though these were secondary to British successes.[33] In the Cold War era, counterintelligence shifted toward ideological penetration and long-term mole hunts between the CIA and KGB. The U.S. Army's Signal Intelligence Service initiated the Venona project in 1943, achieving partial decryption of over 3,000 Soviet diplomatic cables by 1980, which exposed atomic spies like Klaus Fuchs (identified 1949) and networks involving Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs, revealing extensive KGB infiltration of U.S. agencies during and after World War II.[34][35] The CIA's Counterintelligence Staff, led by James Jesus Angleton from 1954 to 1974, pursued aggressive vetting and double-agent operations inspired by Venona revelations, disrupting KGB assets but also fostering internal paranoia that hampered agency efficiency, as Angleton's "mole hunt" consumed resources without conclusively identifying a pervasive Soviet "super-mole."[36][37] The KGB, successor to wartime agencies, conducted reciprocal operations, such as Operation Horizon in 1967–1968, which used double agents to penetrate Western networks and protect Soviet assets, while achieving penetrations like FBI mole Robert Hanssen (recruited 1979) and sustaining influence operations amid mutual defections.[38] These efforts underscored counterintelligence's dual role in defense and offense, with successes like Venona providing empirical evidence of Soviet espionage superiority in the atomic era, though declassified records indicate neither side achieved total dominance, as betrayals and cryptanalytic breakthroughs periodically shifted advantages.[34]Post-Cold War Evolution and Contemporary Shifts

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 25, 1991, counterintelligence efforts in the United States and allied nations pivoted from a primary focus on Soviet state-sponsored espionage to mitigating risks from fragmented post-Soviet entities, nuclear proliferation, and nascent non-state threats. The KGB's restructuring into the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) for external operations and the Federal Security Service (FSB) for internal security did not halt aggressive Russian intelligence activities, as demonstrated by the continued operations of moles like CIA officer Aldrich Ames, who provided secrets to Russian handlers until his arrest on February 21, 1994, compromising numerous assets.[39] FBI counterintelligence expert Robert Hanssen's undetected betrayal, spanning 1985 to 2001 and yielding over $1.4 million in payments, further exposed persistent vulnerabilities in vetting and detection mechanisms inherited from the Cold War era.[40] U.S. intelligence assessments acknowledged underestimating the USSR's internal collapse but rapidly shifted resources toward containing loose WMD materials from former republics, with programs like the Cooperative Threat Reduction initiative launching in 1991 to secure stockpiles.[41][42] The 1990s emphasized economic counterintelligence amid globalization, as foreign actors targeted U.S. technological edge; the FBI's National Counterintelligence Center documented over 400 suspected incidents of corporate espionage by mid-decade, often linked to state-directed efforts from China and Russia seeking dual-use technologies.[43] This era's "rogue states" and asymmetric actors, unchecked by bipolar superpower dynamics, amplified risks of sabotage and technology transfer, prompting legislative responses like the Economic Espionage Act of 1996, which criminalized theft of trade secrets for foreign benefit.[42] Defensive measures expanded to include heightened scrutiny of academic and commercial partnerships, reflecting causal links between open innovation ecosystems and exploitation vulnerabilities. The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks exposed counterintelligence gaps in domestic threat detection, driving integration reforms such as the 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, which centralized oversight under the Director of National Intelligence and bolstered FBI-led counterterrorism fusion centers.[40] Contemporary shifts, often termed the "fourth era" of U.S. counterintelligence, address hybrid domains including cyber intrusions, supply chain compromises, and influence operations, with adversaries like China conducting widespread intellectual property theft—estimated at $225–$600 billion annually in losses—and Russia deploying digital active measures, as detailed in the 2025 U.S. Intelligence Community Annual Threat Assessment.[44][45] Gray zone tactics, blending conventional espionage with disinformation and proxy actions, necessitate offensive adaptations like AI-enhanced anomaly detection and cross-sector collaboration, countering the diffusion of threats across public-private boundaries.[46][47] These evolutions prioritize causal resilience against non-kinetic vectors, informed by empirical failures in prior siloed approaches.Classifications and Frameworks

Defensive Versus Offensive Counterintelligence

Defensive counterintelligence encompasses activities designed to detect, deter, and neutralize threats from foreign intelligence entities targeting an organization's or nation's own secrets, personnel, and operations, emphasizing protection through denial of access and information. These measures include personnel security vetting, insider threat detection, physical and cyber surveillance, and investigations into potential espionage. In the United States, defensive counterintelligence is primarily a responsibility of agencies like the FBI, which focuses on safeguarding domestic assets against penetration. For example, the FBI's multi-year investigation into anomalous financial activities and agent losses culminated in the arrest of CIA counterintelligence officer Aldrich Ames on February 21, 1994, for spying for the Soviet Union and Russia, which had resulted in the compromise and execution of at least ten U.S. assets.[48][48] Such operations prioritize empirical indicators like unexplained wealth or behavioral anomalies to causally link suspects to adversarial activities, preventing further damage through prosecution and damage assessments.[49] Offensive counterintelligence, by contrast, involves proactive efforts to exploit, disrupt, or deceive adversary intelligence services, often through manipulation of their collection processes or assets to generate false intelligence or sow internal distrust. Techniques include recruiting double agents, staging controlled leaks of misinformation, or conducting covert penetrations of enemy networks to feed tailored deceptions. This approach shifts from mere protection to imposing strategic costs on opponents by undermining their decision-making. Historical U.S. and allied examples demonstrate its efficacy in wartime; during World War II, the British MI5's Double-Cross System turned captured or recruited German Abwehr agents into controlled doubles who transmitted fabricated reports, misleading Nazi expectations about the Normandy invasion's scale and timing on June 6, 1944, thereby contributing to Allied operational surprise.[27] In contemporary frameworks, the CIA integrates offensive counterintelligence to target foreign services abroad, such as through agent recruitment within hostile security apparatuses to reveal operations or inject disinformation.[11][50] The delineation between defensive and offensive counterintelligence reflects a causal divide in objectives: the former mitigates vulnerabilities reactively by fortifying barriers against known threat vectors, while the latter exploits adversary weaknesses preemptively to degrade their capabilities. Overlap exists in practice, as defensive detections can yield offensive opportunities, such as flipping captured agents, but institutional divisions—e.g., FBI-led domestic defense versus CIA-directed foreign offense—stem from legal mandates like Executive Order 12333, which delineates roles to balance security with oversight. Empirical data from declassified cases, including over 20 years of undetected Soviet penetration via FBI agent Robert Hanssen until his 2001 arrest, underscore the high failure costs of inadequate defensive postures, while successful offensive deceptions, like those amplifying D-Day feints, have historically amplified military outcomes by factors of operational leverage.[9][17]Counterintelligence by Intelligence Discipline

Counterintelligence efforts are structured around countering specific foreign intelligence collection disciplines, such as human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), imagery intelligence (IMINT), and measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT). This categorization enables targeted defensive and offensive measures to detect, disrupt, and neutralize adversarial collection activities tailored to each method's vulnerabilities. For instance, U.S. Army doctrine defines counterintelligence as a multidiscipline function encompassing counter-HUMINT, counter-IMINT, and counter-SIGINT to degrade threat intelligence and targeting capabilities.[51] These approaches integrate technical, operational, and analytical techniques to protect sensitive information and operations across military and civilian sectors. Counter-HUMINT focuses on identifying and mitigating threats from human sources, including espionage agents, recruiters, and insiders susceptible to coercion or ideological alignment. Operations involve personnel security screening, debriefings of travelers and defectors, and surveillance to detect recruitment attempts or unauthorized contacts. In practice, counter-HUMINT agents conduct investigations into potential insider threats, such as those exploiting access to classified facilities, and employ double-agent handling to feed false information back to adversaries. U.S. military counter-HUMINT emphasizes vetting processes and behavioral analysis to prevent infiltration, as evidenced in field manuals outlining multi-discipline support for defeating human-based collection.[52] Counter-SIGINT targets the interception of communications and electronic emissions by adversaries, prioritizing emissions control, encryption, and secure communication protocols to deny actionable signals. Techniques include frequency hopping, low-probability-of-intercept radar, and monitoring for unauthorized transmissions within operational areas. Marine Corps doctrine highlights counter-SIGINT's role in identifying enemy SIGINT and electronic warfare entities, integrating it with broader defensive measures to protect command-and-control networks during combat. This discipline has evolved with digital threats, incorporating network intrusion detection to counter modern SIGINT platforms that exploit unencrypted data flows.[53] Counter-IMINT employs camouflage, concealment, deception, and decoy operations to obscure visual and electro-optical signatures from aerial, satellite, or ground-based imagery platforms. Procedures involve site hardening, such as netting and multispectral camouflage, and timing operations to evade predictable overflight schedules. Army counterintelligence manuals detail techniques like dispersing assets and simulating false targets to mislead imagery analysis, addressing the global proliferation of reconnaissance systems since the 1990s. Effective counter-IMINT requires coordination with meteorological data to exploit weather obscuration and real-time assessment of adversary imaging capabilities.[54] Emerging disciplines like counter-MASINT address exploitation of physical measurements, such as acoustic, seismic, or chemical signatures, through signature management and sensor denial. This includes material selection for low-observable equipment and environmental masking to evade specialized detection. While less documented in open sources, counter-MASINT integrates with other counterintelligence functions to counter technical intelligence gathering in contested environments. Open-source intelligence (OSINT) countermeasures, though not a traditional "INT," involve controlling public disclosures and monitoring adversary data mining from media and digital footprints to limit inadvertent revelations.[55]Institutional and Sectoral Variations