Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Mollisol

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Mollisol is a soil type which has deep, high organic matter, nutrient-enriched surface soil (a horizon), typically between 60 and 80 cm (24–31 in) in depth. This fertile surface horizon, called a mollic epipedon, is the defining diagnostic feature of Mollisols. Mollic epipedons are created by long-term addition of organic materials derived from plant roots and typically have soft, granular soil structure.

Mollisols typically occur in savannahs and mountain valleys (such as Central Asia, and the North American Great Plains). These environments have historically been strongly influenced by fire and abundant pedoturbation from organisms such as ants and earthworms. It was estimated that in 2003, only 14 to 26 percent of grassland ecosystems remained in a relatively natural state (that is, they were not used for agriculture due to the fertility of the horizon). Globally, they represent ~7% of ice-free land area. As the world's agriculturally most productive soil order, the Mollisols represent one of the most economically important soil orders.

Though most other soil orders known today were formed at the beginning of the Carboniferous Ice Age 280 million years ago, Mollisols are best known from the paleopedological record possibly as early as the Maastrichtian, though confidently found in the Eocene.[1] Their development is very closely associated with cooling and drying of the global climate that occurred during the Oligocene, Miocene and Pliocene.

Suborders

[edit]- Albolls—wet soils; aquic soil moisture regime with an eluvial horizon

- Aquolls—wet soils; aquic soil moisture regime

- Cryolls—cold climate; frigid or cryic soil temperature regime

- Gelolls—very cold climate; mean annual soil temperature < 0 °C

- Rendolls—lime parent material

- Udolls—humid climate; udic moisture regime

- Ustolls—subhumid climate; ustic moisture regime

- Xerolls—Mediterranean climate; xeric moisture regime

Soils which are mostly similar to Mollisols but contain either continuous or discontinuous permafrost, consequently affected by cryoturbation are common in high mountain plateaus of Tibet and the Andean altiplano. Such soils are called Molliturbels or Mollorthels and provide the best grazing land in such cold climates because they are not acidic like many other soils of very cold climates.

Other soils which have a mollic epipedon are classified as Vertisols because high shrink swell characteristics and relatively high clay contents dominate over the mollic epipedon. These soils are especially common in parts of South America in the Paraná River basin receiving abundant but erratic rainfall and extensive deposition of clay-rich minerals from the Andes. Mollic epipedons also occur in some Andisols but the andic properties take precedence.

In the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB), Mollisols are split up into Chernozems, Kastanozems and Phaeozems. Shallow or gravelly Mollisols may belong to the Leptosols. Many Aquolls are Gleysols, Stagnosols or Planosols. Mollisols with a natric horizon belong to the Solonetz.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bellosi1 Sciutto2, Eduardo1 Juan C.2 (January 2002). "Laguna Palacios Formation (San Jorge Basin, Argentina): an Upper Cretaceous loess-paleosol sequence from Central Patagonia". Argentine Meeting on Sedimentology – via ResearchGate.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ IUSS Working Group WRB (2015). "World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, Update 2015" (PDF). World Soil Resources Reports 106, FAO, Rome.

- Brady, N.C. and Weil, R.R. (1996). ‘The Nature and Properties of Soils.’ 11th edition. (Prentice Hall, New Jersey).

- Buol, S.W., Southard, R.J., Graham, R.C., and McDaniel, P.A. (2003). ‘Soil Genesis and Classification.’ 5th edition. (Iowa State University Press - Blackwell, Ames.)

External links

[edit]- "Mollisols". USDA-NRCS. Archived from the original on 2006-05-09. Retrieved 2006-05-14.

- "Mollisols". University of Florida. Archived from the original on April 4, 2006. Retrieved 2006-05-14.

- "Mollisols". University of Idaho. Archived from the original on 2006-05-15. Retrieved 2006-05-14.

Mollisol

View on GrokipediaCharacteristics

Mollic Epipedon

The mollic epipedon serves as the defining surface horizon of Mollisols, characterized by its substantial thickness, dark coloration, elevated organic matter content, and high base saturation, which collectively contribute to exceptional soil fertility. Typically ranging from 18 to 60 cm in depth, this horizon exhibits a moist soil color with a value of ≤3 and chroma of ≤3 according to Munsell notation, reflecting the incorporation of humus that imparts a black to very dark brown appearance. It contains ≥0.6% organic carbon by weight and demonstrates base saturation of ≥50% (determined by NH₄OAc extraction at pH 7), ensuring ample availability of essential cations such as calcium, magnesium, and potassium. These attributes distinguish the mollic epipedon from lighter, less fertile surface horizons in other soil orders.[3][1] Structurally, the mollic epipedon features moderate to strong granular or blocky peds, high porosity exceeding 60% in many cases, and a friable consistency that promotes easy root proliferation and aeration, preventing compaction under grassland vegetation. This soft, crumbly texture arises from repeated wetting-drying cycles and bioturbation, enhancing water retention and drainage while minimizing erosion risk. Biologically, the horizon supports intense microbial activity, with diverse bacterial and fungal communities driving decomposition and nutrient cycling, alongside abundant earthworms and other soil fauna that incorporate plant residues deep into the profile, fostering sustained organic matter buildup. These biotic processes underscore the epipedon's role in maintaining long-term productivity in grassland ecosystems.[3][1][4] In USDA Soil Taxonomy, recognition of the mollic epipedon hinges on precise field and laboratory measurements, including minimum thickness (with adjustments for underlying restrictive layers, such as 10 cm over bedrock), color assessment via Munsell charts, and organic carbon quantification. The organic carbon content is a weighted average of ≥0.6% by weight across the epipedon thickness, with adjustments for low bulk density (higher %OC required if <0.9 g/cm³) and rock fragments to meet the equivalent mass threshold (typically 0.6–1.2 kg/m² depending on depth and texture). Calculations use the formula for mass: 0.1 × %OC × bulk density × thickness. These criteria, established through empirical pedological studies, emphasize the epipedon's uniformity across diverse textures while accommodating variations in parent material influence.[3][1]Subsurface Horizons and Profile

The typical subsurface profile of a Mollisol consists of the mollic epipedon overlying B horizons, such as cambic (Bw), calcic (Bk), or argillic (Bt) horizons, with deeper layers potentially featuring petrocalcic or natric characteristics, extending to total depths of 50 to 200 cm or more in undisturbed settings.[1] These B horizons reflect moderate pedogenic development, with the profile often terminating at a C horizon or root-limiting layer like densic or lithic contacts.[1] Chemically, subsurface horizons maintain high base saturation exceeding 50%, predominantly with calcium and magnesium as exchangeable cations, supporting low acidity and pH values between 6.6 and 7.3.[1] In arid-region Mollisols, such as those in Xerolls or Calciustolls suborders, secondary carbonates accumulate in calcic horizons, often comprising more than 15% CaCO₃ equivalent, which enhances soil stability but can limit permeability if cemented.[1] Physically, these soils display moderate permeability rates, varying from moderately low to slow depending on clay content, with common textures of silty clay loam, loam, or clay loam that promote water retention without excessive runoff.[1] Resistance to erosion is notable due to stable aggregates formed throughout the profile, bolstered by base-rich conditions and organic influences, which reduce susceptibility to structural breakdown under rainfall or tillage.[1] Mollisols lack diagnostic subsurface features like spodic (organic-iron accumulation), oxic (highly weathered clay), or sulfuric horizons, setting them apart from Spodosols, Oxisols, and other orders by emphasizing base-enriched, grassland-derived stability rather than leaching or extreme weathering.[1] Profile depth variations occur regionally; the mollic epipedon itself averages 25 to 60 cm in thickness for the enriched surface zone, while the full profile often exceeds 150 cm in well-developed examples like Udolls, though shallower profiles (50-100 cm) predominate in areas with bedrock or permafrost influences.[1]Formation

Pedogenic Processes

The primary pedogenic process in Mollisols is the humification of organic matter derived from grass roots and surface litter, which leads to the formation of stable organo-mineral complexes that accumulate in the A horizon, enhancing soil structure and fertility.[1] This process involves the microbial decomposition of high-input root biomass, typically from deep-rooted grassland vegetation, resulting in dark-colored humus that binds clay and silt particles.[1] The annual dynamics of organic matter can be conceptualized as net accumulation equaling root biomass production—often 5–7 Mg ha⁻¹ year⁻¹ in prairie systems—minus the decomposition rate, which is moderated by a low carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio of less than 20 in the decomposing material, favoring efficient nutrient recycling over rapid breakdown.[5][6] Base enrichment occurs through the translocation of cations such as calcium (Ca) and magnesium (Mg) released during the weathering of parent materials like loess or glacial till, with these bases cycling via plant uptake and root exudation back into the surface horizon.[1] High evapotranspiration rates in subhumid to semiarid environments limit downward leaching of these bases, promoting their retention and high base saturation (typically >50%) throughout the upper profile.[1][7] This process maintains neutral to slightly alkaline soil pH, preventing acidification and supporting the stability of organic complexes.[1] Mollisols develop over timescales of 1,000 to 10,000 years under relatively stable conditions, with rapid initial accumulation of organic matter in the first few centuries followed by slower profile differentiation over millennia.[8] Bioturbation by soil fauna, including earthworms, ants, and rodents, plays a crucial role in mixing organic inputs downward and aerating the profile, which facilitates even distribution of humus and bases while counteracting horizonation through continuous turnover.[1][4] This biological activity enhances the thickness and uniformity of the mollic epipedon, contributing to the soil's resilience.[8]Environmental Influences

The development of Mollisols is strongly influenced by temperate to semi-arid climatic regimes, characterized by mean annual temperatures ranging from 5 to 20°C and precipitation typically between 300 and 1500 mm, with many regions receiving 500 to 1000 mm annually.[9] These conditions promote moderate leaching that retains bases like calcium and magnesium in the soil profile, preventing significant acidification and supporting the accumulation of a dark, fertile surface horizon.[1] In subhumid areas, seasonal moisture distribution—often under ustic or udic regimes—allows for sufficient wetness during the growing season (at least 90 days) while avoiding excessive drainage that could deplete nutrients.[1] Vegetation plays a pivotal role through perennial grasses in prairie, steppe, or savanna ecosystems, which feature extensive fibrous root systems that deliver high organic inputs to the surface without promoting intense leaching or podzolization.[1] These grasses, common in mid-latitude grasslands, contribute to the mollic epipedon by recycling nutrients efficiently and maintaining high base saturation, as their decomposition yields stable humus rich in cations.[9] In regions like the North American Great Plains or Eurasian steppes, this vegetation cover enhances soil stability and fertility under the prevailing climate. Topography in Mollisol-forming areas is generally level to gently sloping, such as broad plains or stable uplands with slopes under 5%, which minimize erosion and allow for the undisturbed accumulation and preservation of organic-rich horizons over time.[1] These landscapes, often in depositional settings like river valleys or glacial outwash plains, facilitate horizon stability by reducing runoff and promoting uniform pedogenic processes.[10] Parent materials for Mollisols are typically base-rich sediments such as loess, alluvium, or glacial till, which contain weatherable minerals like calcite and provide a reservoir of calcium and other bases essential for the soil's high fertility.[1] These materials, often of Quaternary origin, weather slowly under the moderate climate, releasing nutrients without rapid acidification.[9] Human activities, particularly overgrazing in grassland regions, can accelerate degradation by compacting soil, increasing erosion rates, and diminishing organic matter inputs, thereby threatening the stability of the mollic epipedon.[9] Intensive livestock use disrupts the natural vegetation cover, leading to reduced base retention and potential salinization in semi-arid zones.[1]Distribution

Global Extent

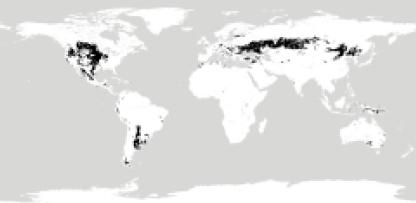

Mollisols occupy approximately 916 million hectares worldwide, accounting for about 7% of the Earth's ice-free land surface.[11] This estimate, derived from comprehensive soil surveys, highlights their significance as a major soil order in global soil resources.[4] They are particularly dominant on three continents: North America, where they cover over 290 million hectares including about 200 million hectares in the United States (roughly 21% of the country's land area), more than 40 million hectares in Canada, and around 50 million hectares in Mexico; Eurasia, spanning approximately 450 million hectares across the steppes of southern Russia (148 million hectares), Ukraine (34 million hectares), and northeast China (35 million hectares); and South America, with about 102 million hectares in the Pampas region of Argentina (89 million hectares) and Uruguay (13 million hectares).[11][12] These soils are zonally distributed in mid-latitude regions, primarily associated with grassland ecosystems in subhumid to semiarid climates, and are largely absent from equatorial zones with high rainfall or polar areas with permafrost.[1] Their prevalence in these temperate continental interiors supports vast expanses of natural prairies and steppes, contributing to their role in global biogeochemical cycles.[11] Globally, the extent of Mollisols has remained relatively stable since the early 2000s, though localized declines have occurred due to urbanization and land conversion, such as urban expansion in the U.S. Great Plains that has reduced prime farmland by notable margins in key metropolitan areas.[14] International soil inventories, including the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the USDA's Soil Taxonomy, facilitate global mapping and classification of Mollisols, correlating them with WRB groups like Chernozems, Phaeozems, and Kastanozems for consistent worldwide assessment.Regional Examples

Mollisols are prominent in North America, particularly across the Great Plains, where they form the dominant soil order and support extensive agriculture. In the United States, these soils cover more than 200 million hectares, spanning from the central plains to eastern Mexico, with chernozem-like variants prevalent in states such as Kansas, where deep, fertile profiles developed under former prairie grasslands.[4][9] In Canada, Mollisols extend over more than 40 million hectares in the prairie provinces, including Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, characterized by dark, humus-rich surface horizons that enhance crop productivity in semi-arid to subhumid climates.[9][11] In Eurasia, Mollisols are exemplified by the deep, black chernozems of the Russian steppes and Ukrainian black earth regions, which together encompass approximately 200 million hectares and represent some of the most fertile soils globally due to high organic matter content from historic steppe vegetation.[4] These variants, often classified as typical or ordinary chernozems, feature thick mollic epipedons exceeding 60 centimeters in depth, with base saturation near 100 percent, supporting vast grain production areas.[9] South American Mollisols are well-represented in the Argentine Pampas, a key grassland expanse where Ustolls predominate in the more arid western portions, contributing to the region's high agricultural productivity through well-drained, loess-derived profiles rich in nutrients.[11] These soils, often Argiudolls in the humid eastern Pampas, cover extensive areas of the Chaco-Pampa plain and sustain intensive cropping systems like soybean and wheat cultivation.[9] Minor occurrences of Mollisols appear in other continents, such as scattered patches in Australia's southeastern grasslands and the highveld regions of South Africa, where they form under temperate conditions but occupy limited extents compared to dominant orders like Alfisols.[16] In the highveld, these soils support maize production on undulating landscapes with moderate fertility.[17] Local variations within Mollisol regions reflect climatic gradients; for instance, semi-arid conditions in the U.S. Midwest foster calcic features, such as secondary carbonate accumulations in subsurface horizons, enhancing soil structure but requiring management for salinity.[18] In contrast, wetter eastern U.S. areas feature Udolls with higher moisture retention and less pronounced calcification, adapted to humid udic regimes east of the Great Plains.[19]Taxonomy

Suborders

Mollisols are classified into eight suborders based primarily on differences in soil moisture and temperature regimes, as well as specific horizon features, all sharing the characteristic mollic epipedon.[20] These suborders were established in the first edition of the USDA Soil Taxonomy in 1975, providing a framework for distinguishing environmental adaptations within the order.[3] Albolls are pale, wet Mollisols featuring an albic (bleached) horizon above an argillic, natric, or fragipan horizon, with aquic conditions within 40-100 cm of the surface, typically in poorly drained lowlands.[20] Aquolls represent saturated Mollisols with aquic conditions within 50 cm, exhibiting redoximorphic features like gray depletions and concentrations, common in wetlands and floodplains.[20] Cryolls are cold Mollisols under a cryic temperature regime (mean annual soil temperature below 8°C at 50 cm depth), occurring in high-latitude or high-elevation areas with well-drained profiles.[20] Gelolls occur in permafrost-influenced environments with a gelic regime (permafrost within 100-200 cm or mean summer soil temperature below 5°C at 50 cm), limiting development and root penetration in polar regions.[20] Rendolls are shallow Mollisols over bedrock, with no argillic, natric, or calcic horizon and a lithic or paralithic contact within 40 cm, often on limestone in karst landscapes.[20] Ustolls have an ustic moisture regime, marked by seasonal dryness (90 or more cumulative dry days) and sufficient moisture (180 or more days when soil temperature exceeds 5°C), corresponding to moist subhumid conditions with annual precipitation around 45-90 cm.[20] Udolls feature a udic moisture regime with consistently moist conditions (90 or more consecutive moist days when soil temperature exceeds 5°C), suited to humid temperate climates.[20] Xerolls exhibit a xeric moisture regime, with dry summers and moist winters typical of Mediterranean climates.[20] Globally, Udolls and Ustolls together comprise approximately 70% of all Mollisols, dominating in humid and subhumid grasslands.[21] Representative examples include Aquolls in Midwest U.S. wetlands, such as those in Iowa and Minnesota floodplains, and Xerolls in California valleys with their seasonal dryness.[20]Diagnostic Criteria

The Mollisol order in Soil Taxonomy is diagnosed by the central requirement of a mollic epipedon combined with a base saturation of 50 percent or more (by sum of cations) to a depth of 75 cm below the soil surface, or to a depth of 125 cm if the soil has free carbonates to that depth or 15 percent or more calcium carbonate equivalent to that depth.[3] This base saturation threshold ensures the soil's fertility and distinguishes Mollisols from more acidic orders like Alfisols or Ultisols.[3] Base saturation is quantified using the formula where CEC is the cation-exchange capacity of the soil determined at pH 7 with ammonium acetate.[3] Suborders within Mollisols are differentiated through a hierarchical key emphasizing soil temperature regimes, moisture regimes, and saturation conditions.[3] For soil temperature, the Cryolls suborder requires a cryic regime, defined as a mean annual soil temperature of less than 8°C (or 0–8°C at a depth of 50 cm in the fine-earth fraction) with no permafrost.[3] Moisture regimes guide suborders like Xerolls, which exhibit a xeric regime characterized by the soil being dry in some part to a depth of at least 20 cm for 45 or more consecutive days following the summer solstice and moist in some part for 45 or more consecutive days following the winter solstice, with dryness occupying 45–60 percent of the time the soil is at field capacity or drier.[3] Saturation defines the Aquolls suborder through aquic conditions, requiring saturation and reduction within 50 cm of the mineral soil surface for 20 or more consecutive days or 30 or more cumulative days during the year in normal years (or a perched water table within 30 cm of the surface).[3] At the great group level, Mollisols are classified based on subordinate diagnostic horizons and features that reflect pedogenic development.[3] For example, the presence of an argillic horizon—evidenced by illuvial clay accumulation increasing the clay content by at least 1.2 times (or 8 percent absolute) relative to the overlying eluvial horizon—defines great groups such as Argiustolls within the Ustolls suborder.[3] Similarly, a calcic horizon, which contains 15 percent or more calcium carbonate equivalent and has at least 5 percent more nodules, masses, or seams than the underlying horizon, characterizes great groups like Calciustolls.[3] The 13th edition of the Keys to Soil Taxonomy (2022) incorporates amendments approved since the 12th edition, including refinements to methods for determining soil temperature and moisture regimes using long-term climate data, enhancing precision in suborder assignments without altering core thresholds for Mollisols.[3] These updates build on prior revisions to aquic conditions, standardizing durations and depths for saturation to better align with field observations.[3]Uses and Management

Agricultural Importance

Mollisols are renowned for their exceptional fertility, stemming from high base saturation and abundant organic matter in the mollic epipedon, which supports nutrient-rich conditions ideal for intensive crop production. These soils underpin a substantial share of global grain output, including approximately 30% of the world's wheat production, much of the corn from the U.S. Midwest (where the country accounts for 27% of global maize), and significant soybean yields, primarily due to the mineralization of organic matter providing available nitrogen levels around 200-300 kg/ha in the surface horizon.[22][23][24] The economic significance of Mollisols is profound, as agriculture on these soils in major regions like the United States and Russia generates hundreds of billions of dollars annually; for instance, U.S. farm cash receipts exceeded $500 billion in recent years (as of 2025), largely from grain and legume crops including those grown on Midwestern Mollisols. These soils are particularly suited to cereals such as wheat, corn, and barley, as well as legumes like soybeans, achieving yield potentials of 5-10 Mg/ha for many crops under rainfed conditions without irrigation, thanks to their favorable water-holding capacity and nutrient retention.[25][11][26] Despite their productivity, Mollisols exhibit limitations, including vulnerability to wind erosion when the protective vegetative cover is removed, which can expose fine-textured surfaces to degradation; however, they demonstrate high resilience when maintained under crop rotation systems that preserve organic matter and soil structure. Globally, Mollisols serve as the foundation of key breadbasket regions, such as the U.S. Midwest, the Russian steppes, and the Argentine Pampas, contributing to food security by supporting production of staple grains and exports.[9][11]Conservation Challenges

Mollisols face significant threats from human activities, including severe erosion exacerbated by intensive farming practices. Historical events like the Dust Bowl in the 1930s demonstrated the vulnerability of these soils, where drought combined with poor land management led to the loss of topsoil across approximately 100 million acres (about 40 million hectares) in the Great Plains region of the United States.[27] This event highlighted how wind erosion can rapidly degrade the fertile mollic epipedon, reducing soil productivity and necessitating long-term recovery efforts. In irrigated agricultural areas, salinization poses another major challenge to Mollisols, particularly in regions like the Pampas of Argentina where supplemental irrigation has been shown to increase soil salinity, sodicity, and alkalinity. Poor irrigation management leads to salt accumulation in the soil profile, impairing water infiltration and nutrient availability, which threatens the sustainability of these inherently fertile soils.[28] Conventional tillage practices contribute to a decline in soil organic matter (SOM) in Mollisols, with global estimates indicating losses of up to 50% of the original carbon pool over several decades due to accelerated decomposition and erosion. In intensively cropped areas, SOM levels have decreased by 1-2% per decade on average, as tillage disrupts soil structure and exposes organic material to oxidation, further diminishing the dark, humus-rich surface horizon characteristic of these soils.[29][30] Climate change exacerbates these issues by altering moisture regimes, with increased drought frequency particularly affecting Xerolls, the drier suborder of Mollisols found in semi-arid regions. Shifting precipitation patterns and higher temperatures can intensify water stress, leading to reduced organic matter accumulation and heightened erosion risks across various suborders.[4] To address these threats, conservation strategies such as no-till farming, cover crops, and buffer strips have proven effective in maintaining soil health in Mollisol regions. No-till practices reduce erosion and help preserve SOM by minimizing soil disturbance, while cover crops and buffer strips enhance water retention and add organic inputs exceeding 1% annually through residue incorporation and root biomass.[31][32] Policy interventions, such as the U.S. Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) established in 1985, have protected approximately 10 million hectares of highly erodible Mollisols by incentivizing landowners to retire marginal cropland from production and implement conservation practices. This program has significantly curbed erosion and supported SOM recovery on enrolled lands.[33] Monitoring degradation in Mollisols often involves calculating soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks using the formula: This approach allows for quantitative tracking of changes in carbon storage, aiding in the assessment of conservation effectiveness and early detection of declines.[34]References

- https://www.[sciencedirect](/page/ScienceDirect).com/science/article/pii/S0016706124001666

- https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-09/Keys-to-[Soil](/page/Soil)-Taxonomy.pdf