Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Monserrate

View on WikipediaMonserrate (Spanish pronunciation: [monseˈrate]; named after Catalan homonym mountain Montserrat) is a mountain over 3,000 metres (10,000 feet) high that overlooks the city center of Bogotá, the capital city of Colombia. It rises to 3,152 meters (10,341 ft) above the sea level, where there is a church (built in the 17th century) with a shrine, devoted to El Señor Caído ("The Fallen Lord").

Key Information

The Mountain, already considered sacred in pre-Columbian times when the area was inhabited by the indigenous Muisca, is a pilgrim destination, as well as a major tourist attraction. In addition to the church, the summit contains restaurants, cafeteria, souvenir shops and many smaller tourist facilities. Monserrate can be accessed by aerial tramway (a cable car known as the teleférico), by funicular, or by climbing, the preferred way of pilgrims. The climbing route was previously closed due to wildfires and landslides caused by a drought, but it reopened in 2017.

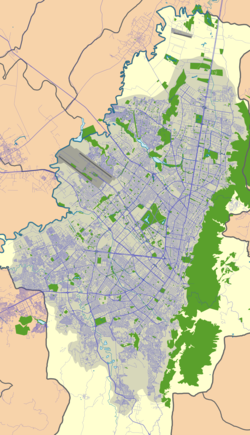

All downtown Bogotá, south Bogotá and some sections of the north of the city are visible facing west, making it a popular destination to watch the sunset over the city. Every year, Monserrate and its neighbour Guadalupe attract many tourists.

History

[edit]Pre-Columbian era

[edit]The history of Monserrate goes back to the pre-Columbian era. Before the Spanish conquest, the Bogotá savanna was inhabited by the Muisca, who were organised in their loose Muisca Confederation. The indigenous people, who had a thorough understanding of astronomy, called Monserrate quijicha caca; "grandmother's foot".[2] At the solstice of June, the Sun, represented in their religion by the solar god Sué, rises exactly from behind Monserrate, as seen from Bolívar Square.[3] The Spanish conquistadors in the early colonial period replaced the Muisca temples by catholic buildings. The first primitive cathedral of Bogotá was constructed on the northeastern corner of Bolívar Square in 1539, a year after the foundation of the capital of the New Kingdom of Granada.

Colonial period

[edit]

In the 1620s, the Cofradia de la Vera Cruz ("Brotherhood of the True Cross") began using the Monserrate's hilltop for religious celebrations. As time passed, many devoted residents of Bogotá began participating in the climb to the hilltop. In 1650, four gentlemen met with the archbishop as well as Juan de Borja, the head of the Tribunal of Santa Fé de Bogotá, in order to secure permission to build a small religious retreat on the top of Monserrate. The founders decided to establish the hermitage retreat in the name of Monserrat's Morena Virgin. Her sanctuary was located in Catalonia, near Barcelona, giving the mountain the name Monserrate. Some people believe Montserrat was chosen to be the patron saint, due to one of the founders, Pedro Solis, having an uncle who had previously served as abbot in the Montserrat sanctuary.

By 1656, Father Rojas had been assigned guarding the sanctuary and ordered the carving of a crucifix and a statue of Jesus Christ. After this statue was taken off the cross, it earned the name "El Señor Caído" ("The Fallen Lord"). Originally, these sculptures were placed inside a small chapel dedicated to the adoration of Christ instead of being placed inside the religious retreat itself. As time passed, more and more people began visiting the sanctuary in order to see the statue of Jesus, rather than the matron saint of Monserrat. By the 19th century, the statue of "The Fallen Lord" had gained so much attention, that the sculpture to the Virgin of Montserrat was removed from the hill as the center piece of the sanctuary and replaced with "El Señor Caído". The mountain has retained the name Monserrate afterwards. Ever since then, for more than four centuries, pilgrims and citizens have hiked the mountain to offer their prayers to the shrine of "El Señor Caído".

Tourism

[edit]Both Monserrate and its neighbor Guadalupe Hill are icons of Bogota's cityscape. The hill is a tourist attraction with access by funicular or cable car (both of which charge a fee) or the pilgrimage hiking trail (free).[4] The hiking path is 2.4 km (1.5 mi), where you can walk up the steep hill on a journey that lasts between 50 min and 3 h, over which the elevation increases 600 m (2,000 ft).[5][6] The average grade of steepness is 25 percent. The hike has been considered dangerous in the past, but now is patrolled by police and is much safer.[7]

Gallery

[edit]-

Guadalupe seen from Monserrate

-

Top of Monserrate

-

Monserrate Monastery

-

Monserrate Monastery

-

Cable car on Monserrate

-

Cable car

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Topographic map of Cerro de Monserrate". opentopomap.org. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Bonilla Romero et al., 2017, p.153

- ^ Bonilla Romero, 2011, p.14

- ^ (in Spanish) Touristic information Monserrate

- ^ Garcia, Brian (2019-01-16). "Experience Cerro Monserrate Bogotá Hike In Colombia". BE Adventure Partners. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ "Hiking the Cerro de Monserrate, Bogota". Free Two Roam. 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ Loeffler, Parry (3 July 2024). "On Google Earth I Found Colombia's Safest Dangerous Place". YouTube.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bonilla Romero, Julio H.; Bustos Velazco, Edier H.; Duvan Reyes, Jaime (2017), "Arqueoastronomía, alineaciones solares de solsticios y equinoccios en Bogotá-Bacatá - Archaeoastronomy, alignment solar from solstices and equinoxes in Bogota-Bacatá", Revista Científica, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, 27: 146–155, retrieved 2017-01-18

- Bonilla Romero, Julio H (2011), "Aproximaciones al observatorio solar de Bacatá-Bogotá-Colombia - Approaches to solar observatory Bacatá-Bogotá-Colombia", Azimut, Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, 3: 9–15, retrieved 2017-01-18