Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Food web

View on Wikipedia

A food web is the natural interconnection of food chains and a graphical representation of what-eats-what in an ecological community. Position in the food web, or trophic level, is used in ecology to broadly classify organisms as autotrophs or heterotrophs. This is a non-binary classification; some organisms (such as carnivorous plants) occupy the role of mixotrophs, or autotrophs that additionally obtain organic matter from non-atmospheric sources.

The linkages in a food web illustrate the feeding pathways, such as where heterotrophs obtain organic matter by feeding on autotrophs and other heterotrophs. The food web is a simplified illustration of the various methods of feeding that link an ecosystem into a unified system of exchange. There are different kinds of consumer–resource interactions that can be roughly divided into herbivory, carnivory, scavenging, and parasitism. Some of the organic matter eaten by heterotrophs, such as sugars, provides energy. Autotrophs and heterotrophs come in all sizes, from microscopic to many tonnes - from cyanobacteria to giant redwoods, and from viruses and bdellovibrio to blue whales.

Charles Elton pioneered the concept of food cycles, food chains, and food size in his classical 1927 book "Animal Ecology"; Elton's 'food cycle' was replaced by 'food web' in a subsequent ecological text. Elton organized species into functional groups, which was the basis for Raymond Lindeman's classic and landmark paper in 1942 on trophic dynamics. Lindeman emphasized the important role of decomposer organisms in a trophic system of classification. The notion of a food web has a historical foothold in the writings of Charles Darwin and his terminology, including an "entangled bank", "web of life", "web of complex relations", and in reference to the decomposition actions of earthworms he talked about "the continued movement of the particles of earth". Even earlier, in 1768 John Bruckner described nature as "one continued web of life".

Food webs are limited representations of real ecosystems as they necessarily aggregate many species into trophic species, which are functional groups of species that have the same predators and prey in a food web. Ecologists use these simplifications in quantitative (or mathematical representation) models of trophic or consumer-resource systems dynamics. Using these models they can measure and test for generalized patterns in the structure of real food web networks. Ecologists have identified non-random properties in the topological structure of food webs. Published examples that are used in meta analysis are of variable quality with omissions. However, the number of empirical studies on community webs is on the rise and the mathematical treatment of food webs using network theory had identified patterns that are common to all.[1] Scaling laws, for example, predict a relationship between the topology of food web predator-prey linkages and levels of species richness.[2]

Taxonomy of a food web

[edit]

Food webs are the road-maps through Darwin's famous 'entangled bank' and have a long history in ecology. Like maps of unfamiliar ground, food webs appear bewilderingly complex. They were often published to make just that point. Yet recent studies have shown that food webs from a wide range of terrestrial, freshwater, and marine communities share a remarkable list of patterns.[5]: 669

Links in food webs map the feeding connections (who eats whom) in an ecological community. Food cycle is an obsolete term that is synonymous with food web. Ecologists can broadly group all life forms into one of two trophic layers, the autotrophs and the heterotrophs. Autotrophs produce more biomass energy, either chemically without the sun's energy or by capturing the sun's energy in photosynthesis, than they use during metabolic respiration. Heterotrophs consume rather than produce biomass energy as they metabolize, grow, and add to levels of secondary production. A food web depicts a collection of polyphagous heterotrophic consumers that network and cycle the flow of energy and nutrients from a productive base of self-feeding autotrophs.[5][6][7]

The base or basal species in a food web are those species without prey and can include autotrophs or saprophytic detritivores (i.e., the community of decomposers in soil, biofilms, and periphyton). Feeding connections in the web are called trophic links. The number of trophic links per consumer is a measure of food web connectance. Food chains are nested within the trophic links of food webs. Food chains are linear (noncyclic) feeding pathways that trace monophagous consumers from a base species up to the top consumer, which is usually a larger predatory carnivore.[8][9][10]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Linkages connect to nodes in a food web, which are aggregates of biological taxa called trophic species. Trophic species are functional groups that have the same predators and prey in a food web. Common examples of an aggregated node in a food web might include parasites, microbes, decomposers, saprotrophs, consumers, or predators, each containing many species in a web that can otherwise be connected to other trophic species.[11][12]

Trophic levels

[edit]

Food webs have trophic levels and positions. Basal species, such as plants, form the first level and are the resource-limited species that feed on no other living creature in the web. Basal species can be autotrophs or detritivores, including "decomposing organic material and its associated microorganisms which we defined as detritus, micro-inorganic material and associated microorganisms (MIP), and vascular plant material."[13]: 94 Most autotrophs capture the sun's energy in chlorophyll, but some autotrophs (the chemolithotrophs) obtain energy by the chemical oxidation of inorganic compounds and can grow in dark environments, such as the sulfur bacterium Thiobacillus, which lives in hot sulfur springs. The top level has top (or apex) predators that no other species kills directly for their food resource needs. The intermediate levels are filled with omnivores that feed on more than one trophic level and cause energy to flow through several food pathways starting from a basal species.[14]

In the simplest scheme, the first trophic level (level 1) is plants, then herbivores (level 2), and then carnivores (level 3). The trophic level equals one more than the chain length, which is the number of links connecting to the base. The base of the food chain (primary producers or detritivores) is set at zero.[5][15] Ecologists identify feeding relations and organize species into trophic species through extensive gut content analysis of different species. The technique has been improved through the use of stable isotopes to better trace energy flow through the web.[16] It was once thought that omnivory was rare, but recent evidence suggests otherwise. This realization has made trophic classifications more complex.[17]

Trophic dynamics and multitrophic interactions

[edit]The trophic level concept was introduced in a historical landmark paper on trophic dynamics in 1942 by Raymond L. Lindeman. The basis of trophic dynamics is the transfer of energy from one part of the ecosystem to another.[15][18] The trophic dynamic concept has served as a useful quantitative heuristic, but it has several major limitations including the precision by which an organism can be allocated to a specific trophic level. Omnivores, for example, are not restricted to any single level. Nonetheless, recent research has found that discrete trophic levels do exist, but "above the herbivore trophic level, food webs are better characterized as a tangled web of omnivores."[17]

A central question in the trophic dynamic literature is the nature of control and regulation over resources and production. Ecologists use simplified one trophic position food chain models (producer, carnivore, decomposer). Using these models, ecologists have tested various types of ecological control mechanisms. For example, herbivores generally have an abundance of vegetative resources, which meant that their populations were largely controlled or regulated by predators. This is known as the top-down hypothesis or 'green-world' hypothesis. Alternatively to the top-down hypothesis, not all plant material is edible and the nutritional quality or antiherbivore defenses of plants (structural and chemical) suggests a bottom-up form of regulation or control.[19][20][21] Recent studies have concluded that both "top-down" and "bottom-up" forces can influence community structure and the strength of the influence is environmentally context dependent.[22][23] These complex multitrophic interactions involve more than two trophic levels in a food web.[24] For example, such interactions have been discovered in the context of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and aphid herbivores that utilize the same plant species.[25]

Another example of a multitrophic interaction is a trophic cascade, in which predators help to increase plant growth and prevent overgrazing by suppressing herbivores. Links in a food-web illustrate direct trophic relations among species, but there are also indirect effects that can alter the abundance, distribution, or biomass in the trophic levels. For example, predators eating herbivores indirectly influence the control and regulation of primary production in plants. Although the predators do not eat the plants directly, they regulate the population of herbivores that are directly linked to plant trophism. The net effect of direct and indirect relations is called trophic cascades. Trophic cascades are separated into species-level cascades, where only a subset of the food-web dynamic is impacted by a change in population numbers, and community-level cascades, where a change in population numbers has a dramatic effect on the entire food-web, such as the distribution of plant biomass.[26]

The field of chemical ecology has elucidated multitrophic interactions that entail the transfer of defensive compounds across multiple trophic levels.[27] For example, certain plant species in the Castilleja and Plantago genera have been found to produce defensive compounds called iridoid glycosides that are sequestered in the tissues of the Taylor's checkerspot butterfly larvae that have developed a tolerance for these compounds and are able to consume the foliage of these plants.[28][29] These sequestered iridoid glycosides then confer chemical protection against bird predators to the butterfly larvae.[28][29] Another example of this sort of multitrophic interaction in plants is the transfer of defensive alkaloids produced by endophytes living within a grass host to a hemiparasitic plant that is also using the grass as a host.[30]

Energy flow and biomass

[edit]

The Law of Conservation of Mass dates from Antoine Lavoisier's 1789 discovery that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions. In other words, the mass of any one element at the beginning of a reaction will equal the mass of that element at the end of the reaction.[31]: 11

Food webs depict energy flow via trophic linkages. Energy flow is directional, which contrasts against the cyclic flows of material through the food web systems.[33] Energy flow "typically includes production, consumption, assimilation, non-assimilation losses (feces), and respiration (maintenance costs)."[7]: 5 In a very general sense, energy flow (E) can be defined as the sum of metabolic production (P) and respiration (R), such that E=P+R.

Biomass represents stored energy. However, concentration and quality of nutrients and energy is variable. Many plant fibers, for example, are indigestible to many herbivores leaving grazer community food webs more nutrient limited than detrital food webs where bacteria are able to access and release the nutrient and energy stores.[34][35] "Organisms usually extract energy in the form of carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins. These polymers have a dual role as supplies of energy as well as building blocks; the part that functions as energy supply results in the production of nutrients (and carbon dioxide, water, and heat). Excretion of nutrients is, therefore, basic to metabolism."[35]: 1230–1231 The units in energy flow webs are typically a measure mass or energy per m2 per unit time. Different consumers are going to have different metabolic assimilation efficiencies in their diets. Each trophic level transforms energy into biomass. Energy flow diagrams illustrate the rates and efficiency of transfer from one trophic level into another and up through the hierarchy.[36][37]

It is the case that the biomass of each trophic level decreases from the base of the chain to the top. This is because energy is lost to the environment with each transfer as entropy increases. About eighty to ninety percent of the energy is expended for the organism's life processes or is lost as heat or waste. Only about ten to twenty percent of the organism's energy is generally passed to the next organism.[38] The amount can be less than one percent in animals consuming less digestible plants, and it can be as high as forty percent in zooplankton consuming phytoplankton.[39] Graphic representations of the biomass or productivity at each tropic level are called ecological pyramids or trophic pyramids. The transfer of energy from primary producers to top consumers can also be characterized by energy flow diagrams.[40]

Food chain

[edit]A common metric used to quantify food web trophic structure is food chain length. Food chain length is another way of describing food webs as a measure of the number of species encountered as energy or nutrients move from the plants to top predators.[41]: 269 There are different ways of calculating food chain length depending on what parameters of the food web dynamic are being considered: connectance, energy, or interaction.[41] In its simplest form, the length of a chain is the number of links between a trophic consumer and the base of the web. The mean chain length of an entire web is the arithmetic average of the lengths of all chains in a food web.[42][14]

In a simple predator-prey example, a deer is one step removed from the plants it eats (chain length = 1) and a wolf that eats the deer is two steps removed from the plants (chain length = 2). The relative amount or strength of influence that these parameters have on the food web address questions about:

- the identity or existence of a few dominant species (called strong interactors or keystone species)

- the total number of species and food-chain length (including many weak interactors) and

- how community structure, function and stability is determined.[43][44]

Ecological pyramids

[edit]

In a pyramid of numbers, the number of consumers at each level decreases significantly, so that a single top consumer, (e.g., a polar bear or a human), will be supported by a much larger number of separate producers. There is usually a maximum of four or five links in a food chain, although food chains in aquatic ecosystems are more often longer than those on land. Eventually, all the energy in a food chain is dispersed as heat.[6]

Ecological pyramids place the primary producers at the base. They can depict different numerical properties of ecosystems, including numbers of individuals per unit of area, biomass (g/m2), and energy (k cal m−2 yr−1). The emergent pyramidal arrangement of trophic levels with amounts of energy transfer decreasing as species become further removed from the source of production is one of several patterns that is repeated amongst the planets ecosystems.[4][5][45] The size of each level in the pyramid generally represents biomass, which can be measured as the dry weight of an organism.[46] Autotrophs may have the highest global proportion of biomass, but they are closely rivaled or surpassed by microbes.[47][48]

Pyramid structure can vary across ecosystems and across time. In some instances biomass pyramids can be inverted. This pattern is often identified in aquatic and coral reef ecosystems. The pattern of biomass inversion is attributed to different sizes of producers. Aquatic communities are often dominated by producers that are smaller than the consumers that have high growth rates. Aquatic producers, such as planktonic algae or aquatic plants, lack the large accumulation of secondary growth as exists in the woody trees of terrestrial ecosystems. However, they are able to reproduce quickly enough to support a larger biomass of grazers. This inverts the pyramid. Primary consumers have longer lifespans and slower growth rates that accumulates more biomass than the producers they consume. Phytoplankton live just a few days, whereas the zooplankton eating the phytoplankton live for several weeks and the fish eating the zooplankton live for several consecutive years.[49] Aquatic predators also tend to have a lower death rate than the smaller consumers, which contributes to the inverted pyramidal pattern. Population structure, migration rates, and environmental refuge for prey are other possible causes for pyramids with biomass inverted. Energy pyramids, however, will always have an upright pyramid shape if all sources of food energy are included and this is dictated by the second law of thermodynamics.[6][50]

Material flux and recycling

[edit]Many of the Earth's elements and minerals (or mineral nutrients) are contained within the tissues and diets of organisms. Hence, mineral and nutrient cycles trace food web energy pathways. Ecologists employ stoichiometry to analyze the ratios of the main elements found in all organisms: carbon (C), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P). There is a large transitional difference between many terrestrial and aquatic systems as C:P and C:N ratios are much higher in terrestrial systems while N:P ratios are equal between the two systems.[51][52][53] Mineral nutrients are the material resources that organisms need for growth, development, and vitality. Food webs depict the pathways of mineral nutrient cycling as they flow through organisms.[6][18] Most of the primary production in an ecosystem is not consumed, but is recycled by detritus back into useful nutrients.[54] Many of the Earth's microorganisms are involved in the formation of minerals in a process called biomineralization.[55][56][57] Bacteria that live in detrital sediments create and cycle nutrients and biominerals.[58] Food web models and nutrient cycles have traditionally been treated separately, but there is a strong functional connection between the two in terms of stability, flux, sources, sinks, and recycling of mineral nutrients.[59][60]

Kinds of food webs

[edit]Food webs are necessarily aggregated and only illustrate a tiny portion of the complexity of real ecosystems. For example, the number of species on the planet are likely in the general order of 107, over 95% of these species consist of microbes and invertebrates, and relatively few have been named or classified by taxonomists.[61][62][63] It is explicitly understood that natural systems are 'sloppy' and that food web trophic positions simplify the complexity of real systems that sometimes overemphasize many rare interactions. Most studies focus on the larger influences where the bulk of energy transfer occurs.[19] "These omissions and problems are causes for concern, but on present evidence do not present insurmountable difficulties."[5]: 669

There are different kinds or categories of food webs:

- Source web - one or more node(s), all of their predators, all the food these predators eat, and so on.

- Sink web - one or more node(s), all of their prey, all the food that these prey eat, and so on.

- Community (or connectedness) web - a group of nodes and all the connections of who eats whom.

- Energy flow web - quantified fluxes of energy between nodes along links between a resource and a consumer.[5][46]

- Paleoecological web - a web that reconstructs ecosystems from the fossil record.[64]

- Functional web - emphasizes the functional significance of certain connections having strong interaction strength and greater bearing on community organization, more so than energy flow pathways. Functional webs have compartments, which are sub-groups in the larger network where there are different densities and strengths of interaction.[44][65] Functional webs emphasize that "the importance of each population in maintaining the integrity of a community is reflected in its influence on the growth rates of other populations."[46]: 511

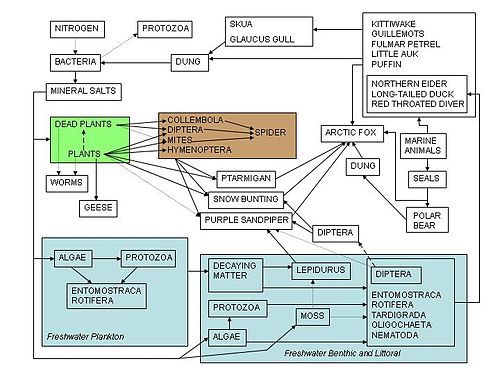

Within these categories, food webs can be further organized according to the different kinds of ecosystems being investigated. For example, human food webs, agricultural food webs, detrital food webs, marine food webs, aquatic food webs, soil food webs, Arctic (or polar) food webs, terrestrial food webs, and microbial food webs. These characterizations stem from the ecosystem concept, which assumes that the phenomena under investigation (interactions and feedback loops) are sufficient to explain patterns within boundaries, such as the edge of a forest, an island, a shoreline, or some other pronounced physical characteristic.[66][67][68]

Detrital web

[edit]In a detrital web, plant and animal matter is broken down by decomposers, e.g., bacteria and fungi, and moves to detritivores and then carnivores.[69] There are often relationships between the detrital web and the grazing web. Mushrooms produced by decomposers in the detrital web become a food source for deer, squirrels, and mice in the grazing web. Earthworms eaten by robins are detritivores consuming decaying leaves.[70]

"Detritus can be broadly defined as any form of non-living organic matter, including different types of plant tissue (e.g. leaf litter, dead wood, aquatic macrophytes, algae), animal tissue (carrion), dead microbes, faeces (manure, dung, faecal pellets, guano, frass), as well as products secreted, excreted or exuded from organisms (e.g. extra-cellular polymers, nectar, root exudates and leachates, dissolved organic matter, extra-cellular matrix, mucilage). The relative importance of these forms of detritus, in terms of origin, size and chemical composition, varies across ecosystems."[54]: 585

Quantitative food webs

[edit]Ecologists collect data on trophic levels and food webs to statistically model and mathematically calculate parameters, such as those used in other kinds of network analysis (e.g., graph theory), to study emergent patterns and properties shared among ecosystems. There are different ecological dimensions that can be mapped to create more complicated food webs, including: species composition (type of species), richness (number of species), biomass (the dry weight of plants and animals), productivity (rates of conversion of energy and nutrients into growth), and stability (food webs over time). A food web diagram illustrating species composition shows how change in a single species can directly and indirectly influence many others. Microcosm studies are used to simplify food web research into semi-isolated units such as small springs, decaying logs, and laboratory experiments using organisms that reproduce quickly, such as daphnia feeding on algae grown under controlled environments in jars of water.[43][71]

While the complexity of real food webs connections are difficult to decipher, ecologists have found mathematical models on networks an invaluable tool for gaining insight into the structure, stability, and laws of food web behaviours relative to observable outcomes. "Food web theory centers around the idea of connectance."[72]: 1648 Quantitative formulas simplify the complexity of food web structure. The number of trophic links (tL), for example, is converted into a connectance value:

- ,

where, S(S-1)/2 is the maximum number of binary connections among S species.[72] "Connectance (C) is the fraction of all possible links that are realized (L/S2) and represents a standard measure of food web complexity..."[73]: 12913 The distance (d) between every species pair in a web is averaged to compute the mean distance between all nodes in a web (D)[73] and multiplied by the total number of links (L) to obtain link-density (LD), which is influenced by scale-dependent variables such as species richness. These formulas are the basis for comparing and investigating the nature of non-random patterns in the structure of food web networks among many different types of ecosystems.[73][74]

Scaling laws, complexity, chaos, and pattern correlates are common features attributed to food web structure.[75][76]

Complexity and stability

[edit]

Food webs are extremely complex. Complexity is a term that conveys the mental intractability of understanding all possible higher-order effects in a food web. Sometimes in food web terminology, complexity is defined as product of the number of species and connectance.,[77][78][79] though there have been criticisms of this definition and other proposed methods for measuring network complexity.[80] Connectance is "the fraction of all possible links that are realized in a network".[81]: 12917 These concepts were derived and stimulated through the suggestion that complexity leads to stability in food webs, such as increasing the number of trophic levels in more species rich ecosystems. This hypothesis was challenged through mathematical models suggesting otherwise, but subsequent studies have shown that the premise holds in real systems.[77][74]

At different levels in the hierarchy of life, such as the stability of a food web, "the same overall structure is maintained in spite of an ongoing flow and change of components."[82]: 476 The farther a living system (e.g., ecosystem) sways from equilibrium, the greater its complexity.[82] Complexity has multiple meanings in the life sciences and in the public sphere that confuse its application as a precise term for analytical purposes in science.[79][83] Complexity in the life sciences (or biocomplexity) is defined by the "properties emerging from the interplay of behavioral, biological, physical, and social interactions that affect, sustain, or are modified by living organisms, including humans".[84]: 1018

Several concepts have emerged from the study of complexity in food webs. Complexity explains many principals pertaining to self-organization, non-linearity, interaction, cybernetic feedback, discontinuity, emergence, and stability in food webs. Nestedness, for example, is defined as "a pattern of interaction in which specialists interact with species that form perfect subsets of the species with which generalists interact",[85]: 575 "—that is, the diet of the most specialized species is a subset of the diet of the next more generalized species, and its diet a subset of the next more generalized, and so on."[86] Until recently, it was thought that food webs had little nested structure, but empirical evidence shows that many published webs have nested subwebs in their assembly.[87]

Food webs are complex networks. As networks, they exhibit similar structural properties and mathematical laws that have been used to describe other complex systems, such as small world and scale free properties. The small world attribute refers to the many loosely connected nodes, non-random dense clustering of a few nodes (i.e., trophic or keystone species in ecology), and small path length compared to a regular lattice.[81][88] "Ecological networks, especially mutualistic networks, are generally very heterogeneous, consisting of areas with sparse links among species and distinct areas of tightly linked species. These regions of high link density are often referred to as cliques, hubs, compartments, cohesive sub-groups, or modules...Within food webs, especially in aquatic systems, nestedness appears to be related to body size because the diets of smaller predators tend to be nested subsets of those of larger predators (Woodward & Warren 2007; YvonDurocher et al. 2008), and phylogenetic constraints, whereby related taxa are nested based on their common evolutionary history, are also evident (Cattin et al. 2004)."[89]: 257 "Compartments in food webs are subgroups of taxa in which many strong interactions occur within the subgroups and few weak interactions occur between the subgroups. Theoretically, compartments increase the stability in networks, such as food webs."[65]

Food webs are also complex in the way that they change in scale, seasonally, and geographically. The components of food webs, including organisms and mineral nutrients, cross the thresholds of ecosystem boundaries. This has led to the concept or area of study known as cross-boundary subsidy.[66][67] "This leads to anomalies, such as food web calculations determining that an ecosystem can support one half of a top carnivore, without specifying which end."[68] Nonetheless, real differences in structure and function have been identified when comparing different kinds of ecological food webs, such as terrestrial vs. aquatic food webs.[90]

History of food webs

[edit]

Food webs serve as a framework to help ecologists organize the complex network of interactions among species observed in nature and around the world. One of the earliest descriptions of a food chain was described by a medieval Afro-Arab scholar named Al-Jahiz: "All animals, in short, cannot exist without food, neither can the hunting animal escape being hunted in his turn."[91]: 143 The earliest graphical depiction of a food web was by Lorenzo Camerano in 1880, followed independently by those of Pierce and colleagues in 1912 and Victor Shelford in 1913.[92][93] Two food webs about herring were produced by Victor Summerhayes and Charles Elton[94] and Alister Hardy[95] in 1923 and 1924. Charles Elton subsequently pioneered the concept of food cycles, food chains, and food size in his classical 1927 book "Animal Ecology"; Elton's 'food cycle' was replaced by 'food web' in a subsequent ecological text.[96] After Charles Elton's use of food webs in his 1927 synthesis,[97] they became a central concept in the field of ecology. Elton[96] organized species into functional groups, which formed the basis for the trophic system of classification in Raymond Lindeman's classic and landmark paper in 1942 on trophic dynamics.[18][44][98] The notion of a food web has a historical foothold in the writings of Charles Darwin and his terminology, including an "entangled bank", "web of life", "web of complex relations", and in reference to the decomposition actions of earthworms he talked about "the continued movement of the particles of earth". Even earlier, in 1768 John Bruckner described nature as "one continued web of life".[5][99][100][101]

Interest in food webs increased after Robert Paine's experimental and descriptive study of intertidal shores[102] suggesting that food web complexity was key to maintaining species diversity and ecological stability. Many theoretical ecologists, including Sir Robert May[103] and Stuart Pimm,[104] were prompted by this discovery and others to examine the mathematical properties of food webs.

See also

[edit]- Anti-predator adaptation – Defensive feature of prey for selective advantage

- Apex predator – Predator at the top of a food chain

- Aquatic-terrestrial subsidies – Aspect of ecological connectivity

- Balance of nature – Superseded ecological theory

- Biodiversity – Variety and variability of life forms

- Biogeochemical cycle – Chemical transfer pathway between Earth's biological and non-biological parts

- Consumer–resource interactions – Dietary interactions between species

- Ecological network – Representation of the biotic interactions in an ecosystem

- Food system – Processes by which nutritional substances are grown, raised, packaged and distributed

- Food web of the San Francisco Estuary

- List of feeding behaviours

- Marine food web – Marine consumer-resource system

- Microbial food web – Biological food web

- Natural environment – Living and non-living things on Earth

- Soil food web – Complex living system in the soil

- Tritrophic interactions in plant defense – Ecological interactions

- Trophic ecology of kelp forests – Underwater areas highly dense with kelp

- Trophic mutualism

- Trophic relationships in lakes – Type of ecosystem

- Trophic relationships in rivers – Type of aquatic ecosystem with flowing freshwater

References

[edit]- ^ Cohen, J.E.; Briand, F.; Newman, C.M. (1990). Community Food Webs: Data and Theory. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer. p. 308. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-83784-5. ISBN 9783642837869.

- ^ Briand, F.; Cohen, J.E. (19 January 1984). "Community food webs have scale-invariant structure". Nature. 307 (5948): 264–267. Bibcode:1984Natur.307..264B. doi:10.1038/307264a0. S2CID 4319708.

- ^ Kormondy, E. J. (1996). Concepts of ecology (4th ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-13-478116-7.

- ^ a b Proulx, S. R.; Promislow, D. E. L.; Phillips, P. C. (2005). "Network thinking in ecology and evolution" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 20 (6): 345–353. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.004. PMID 16701391. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pimm, S. L.; Lawton, J. H.; Cohen, J. E. (1991). "Food web patterns and their consequences" (PDF). Nature. 350 (6320): 669–674. Bibcode:1991Natur.350..669P. doi:10.1038/350669a0. S2CID 4267587. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-10. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ a b c d e f Odum, E. P.; Barrett, G. W. (2005). Fundamentals of Ecology (5th ed.). Brooks/Cole, a part of Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-42066-6. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20.

- ^ a b Benke, A. C. (2010). "Secondary production". Nature Education Knowledge. 1 (8): 5.

- ^ Allesina, S.; Alonso, D.; Pascual, M. (2008). "A general model for food web structure" (PDF). Science. 320 (5876): 658–661. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..658A. doi:10.1126/science.1156269. PMID 18451301. S2CID 11536563. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Azam, F.; Fenche, T.; Field, J. G.; Gra, J. S.; Meyer-Reil, L. A.; Thingstad, F. (1983). "The ecological role of water-column microbes in the sea" (PDF). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 10: 257–263. Bibcode:1983MEPS...10..257A. doi:10.3354/meps010257.

- ^ Uroz, S.; Calvarus, C.; Turpault, M.; Frey-Klett, P. (2009). "Mineral weathering by bacteria: ecology, actors and mechanisms" (PDF). Trends in Microbiology. 17 (8): 378–387. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.004. PMID 19660952.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Williams, R. J.; Martinez, N. D. (2000). "Simple rules yield complex food webs" (PDF). Nature. 404 (6774): 180–183. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..180W. doi:10.1038/35004572. PMID 10724169. S2CID 205004984. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ Post, D. M. (2002). "The long and short of food chain length" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 17 (6): 269–277. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02455-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Tavares-Cromar, A. F.; Williams, D. D. (1996). "The importance of temporal resolution in food web analysis: Evidence from a detritus-based stream" (PDF). Ecological Monographs. 66 (1): 91–113. Bibcode:1996EcoM...66...91T. doi:10.2307/2963482. hdl:1807/768. JSTOR 2963482.

- ^ a b Pimm, S. L. (1979). "The structure of food webs" (PDF). Theoretical Population Biology. 16 (2): 144–158. Bibcode:1979TPBio..16..144P. doi:10.1016/0040-5809(79)90010-8. PMID 538731. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ a b Cousins, S. (1985-07-04). "Ecologists build pyramids again". New Scientist. 1463: 50–54.[permanent dead link]

- ^ McCann, K. (2007). "Protecting biostructure". Nature. 446 (7131): 29. Bibcode:2007Natur.446...29M. doi:10.1038/446029a. PMID 17330028. S2CID 4428058.

- ^ a b Thompson, R. M.; Hemberg, M.; Starzomski, B. M.; Shurin, J. B. (March 2007). "Trophic levels and trophic tangles: The prevalence of omnivory in real food webs" (PDF). Ecology. 88 (3): 612–617. Bibcode:2007Ecol...88..612T. doi:10.1890/05-1454. PMID 17503589. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ a b c Lindeman, R. L. (1942). "The trophic-dynamic aspect of ecology" (PDF). Ecology. 23 (4): 399–417. Bibcode:1942Ecol...23..399L. doi:10.2307/1930126. JSTOR 1930126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-29. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ a b Hairston, N. G. (1993). "Cause-effect relationships in energy flow, trophic structure, and interspecific interactions" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 142 (3): 379–411. doi:10.1086/285546. hdl:1813/57238. S2CID 55279332. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ^ Fretwell, S. D. (1987). "Food chain dynamics: The central theory of ecology?" (PDF). Oikos. 50 (3): 291–301. Bibcode:1987Oikos..50..291F. doi:10.2307/3565489. JSTOR 3565489. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ^ Polis, G. A.; Strong, D. R. (1996). "Food web complexity and community dynamics" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 147 (5): 813–846. doi:10.1086/285880. S2CID 85155900.

- ^ Hoekman, D. (2010). "Turning up the head: Temperature influences the relative importance of top-down and bottom-up effects" (PDF). Ecology. 91 (10): 2819–2825. Bibcode:2010Ecol...91.2819H. doi:10.1890/10-0260.1. PMID 21058543.

- ^ Schmitz, O. J. (2008). "Herbivory from individuals to ecosystems". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 39: 133–152. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173418. S2CID 86686057.

- ^ Tscharntke, T.; Hawkins, B. A., eds. (2002). Multitrophic Level Interactions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-0-521-79110-6.

- ^ Babikova, Zdenka; Gilbert, Lucy; Bruce, Toby; Dewhirst, Sarah; Pickett, John A.; Johnson, David (April 2014). "Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and aphids interact by changing host plant quality and volatile emission". Functional Ecology. 28 (2): 375–385. Bibcode:2014FuEco..28..375B. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.12181. JSTOR 24033672.

- ^ Polis, G.A.; et al. (2000). "When is a trophic cascade a trophic cascade?" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 15 (11): 473–5. Bibcode:2000TEcoE..15..473P. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01971-6. PMID 11050351.

- ^ Tscharntke, Teja; Hawkins, Bradford A. (2002). Multitrophic Level Interactions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 10, 72. ISBN 978-0-511-06719-8.

- ^ a b Haan, Nate L.; Bakker, Jonathan D.; Bowers, M. Deane (14 January 2021). "Preference, performance, and chemical defense in an endangered butterfly using novel and ancestral host plants". Scientific Reports. 11 (992): 992. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11..992H. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80413-y. PMC 7809109. PMID 33446768.

- ^ a b Haan, Nate L.; Bakker, Jonathan D.; Bowers, M. Deane (May 2018). "Hemiparasites can transmit indirect effects from their host plants to herbivores". Ecology. 99 (2): 399–410. Bibcode:2018Ecol...99..399H. doi:10.1002/ecy.2087. JSTOR 26624251. PMID 29131311. Retrieved 2022-05-02.

- ^ Lehtonen, Päivi; Helander, Marjo; Wink, Michael; Sporer, Frank; Saikkonen, Kari (12 October 2005). "Transfer of endophyte-origin defensive alkaloids from a grass to a hemiparasitic plant". Ecology Letters. 8 (12): 1256–1263. Bibcode:2005EcolL...8.1256L. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00834.x.

- ^ Sterner, R. W.; Small, G. E.; Hood, J. M. "The conservation of mass". Nature Education Knowledge. 2 (1): 11.

- ^ Odum, H. T. (1988). "Self-organization, transformity, and information". Science. 242 (4882): 1132–1139. Bibcode:1988Sci...242.1132O. doi:10.1126/science.242.4882.1132. hdl:11323/5713. JSTOR 1702630. PMID 17799729. S2CID 27517361.

- ^ Odum, E. P. (1968). "Energy flow in ecosystems: A historical review". American Zoologist. 8 (1): 11–18. doi:10.1093/icb/8.1.11.

- ^ Mann, K. H. (1988). "Production and use of detritus in various freshwater, estuarine, and coastal marine ecosystems" (PDF). Limnol. Oceanogr. 33 (2): 910–930. doi:10.4319/lo.1988.33.4_part_2.0910. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- ^ a b Koijman, S. A. L. M.; Andersen, T.; Koo, B. W. (2004). "Dynamic energy budget representations of stoichiometric constraints on population dynamics" (PDF). Ecology. 85 (5): 1230–1243. Bibcode:2004Ecol...85.1230K. doi:10.1890/02-0250.

- ^ Anderson, K. H.; Beyer, J. E.; Lundberg, P. (2009). "Trophic and individual efficiencies of size-structured communities". Proc Biol Sci. 276 (1654): 109–114. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0951. PMC 2614255. PMID 18782750.

- ^ Benke, A. C. (2011). "Secondary production, quantitative food webs, and trophic position". Nature Education Knowledge. 2 (2): 2.

- ^ Spellman, Frank R. (2008). The Science of Water: Concepts and Applications. CRC Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4200-5544-3.

- ^ Kent, Michael (2000). Advanced Biology. Oxford University Press US. p. 511. ISBN 978-0-19-914195-1.

- ^ Kent, Michael (2000). Advanced Biology. Oxford University Press US. p. 510. ISBN 978-0-19-914195-1.

- ^ a b Post, D. M. (1993). "The long and short of food-chain length". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 17 (6): 269–277. doi:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02455-2.

- ^ Odum, E. P.; Barrett, G. W. (2005). Fundamentals of ecology. Brooks Cole. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-534-42066-6.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Worm, B.; Duffy, J.E. (2003). "Biodiversity, productivity and stability in real food webs". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 18 (12): 628–632. Bibcode:2003TEcoE..18..628W. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.003.

- ^ a b c Paine, R. T. (1980). "Food webs: Linkage, interaction strength and community infrastructure". Journal of Animal Ecology. 49 (3): 666–685. Bibcode:1980JAnEc..49..666P. doi:10.2307/4220. JSTOR 4220. S2CID 55981512.

- ^ Raffaelli, D. (2002). "From Elton to mathematics and back again". Science. 296 (5570): 1035–1037. doi:10.1126/science.1072080. PMID 12004106. S2CID 177263265.

- ^ a b c Rickleffs, Robert E. (1996). The Economy of Nature. University of Chicago Press. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-7167-3847-3.

- ^ Whitman, W. B.; Coleman, D. C.; Wieb, W. J. (1998). "Prokaryotes: The unseen majority". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95 (12): 6578–83. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.6578W. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.12.6578. PMC 33863. PMID 9618454.

- ^ Groombridge, B.; Jenkins, M. (2002). World Atlas of Biodiversity: Earth's Living Resources in the 21st Century. World Conservation Monitoring Centre, United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN 978-0-520-23668-4.

- ^ Spellman, Frank R. (2008). The Science of Water: Concepts and Applications. CRC Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4200-5544-3.

- ^ Wang, H.; Morrison, W.; Singh, A.; Weiss, H. (2009). "Modeling inverted biomass pyramids and refuges in ecosystems" (PDF). Ecological Modelling. 220 (11): 1376–1382. Bibcode:2009EcMod.220.1376W. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2009.03.005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ^ Pomeroy, L. R. (1970). "The strategy of mineral cycling". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1: 171–190. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.01.110170.001131. JSTOR 2096770.

- ^ Elser, J. J.; Fagan, W. F.; Donno, R. F.; Dobberfuhl, D. R.; Folarin, A.; Huberty, A.; et al. (2000). "Nutritional constraints in terrestrial and freshwater food webs" (PDF). Nature. 408 (6812): 578–580. Bibcode:2000Natur.408..578E. doi:10.1038/35046058. PMID 11117743. S2CID 4408787.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Koch, P. L.; Fox-Dobbs, K.; Newsom, S. D. "The isotopic ecology of fossil vertebrates and conservation paleobiology". In Diet, G. P.; Flessa, K. W. (eds.). Conservation paleobiology: Using the past to manage for the future, Paleontological Society short course (PDF). The Paleontological Society Papers. Vol. 15. pp. 95–112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2011-06-14.

- ^ a b Moore, J. C.; Berlow, E. L.; Coleman, D. C.; de Ruiter, P. C.; Dong, Q.; Hastings, A.; et al. (2004). "Detritus, trophic dynamics and biodiversity". Ecology Letters. 7 (7): 584–600. Bibcode:2004EcolL...7..584M. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00606.x. S2CID 2635427.

- ^ H. A., Lowenstam (1981). "Minerals formed by organisms". Science. 211 (4487): 1126–1131. Bibcode:1981Sci...211.1126L. doi:10.1126/science.7008198. JSTOR 1685216. PMID 7008198. S2CID 31036238.

- ^ Warren, L. A.; Kauffman, M. E. (2003). "Microbial geoengineers". Science. 299 (5609): 1027–1029. doi:10.1126/science.1072076. JSTOR 3833546. PMID 12586932. S2CID 19993145.

- ^ González-Muñoz, M. T.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Martínez-Ruiz, F.; Arias, J. M.; Merroun, M. L.; Rodriguez-Gallego, M. (2010). "Bacterial biomineralization: new insights from Myxococcus-induced mineral precipitation". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 336 (1): 31–50. Bibcode:2010GSLSP.336...31G. doi:10.1144/SP336.3. S2CID 130343033.

- ^ Gonzalez-Acosta, B.; Bashan, Y.; Hernandez-Saavedra, N. Y.; Ascencio, F.; De la Cruz-Agüero, G. (2006). "Seasonal seawater temperature as the major determinant for populations of culturable bacteria in the sediments of an intact mangrove in an arid region" (PDF). FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 55 (2): 311–321. Bibcode:2006FEMME..55..311G. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2005.00019.x. PMID 16420638.

- ^ DeAngelis, D. L.; Mulholland, P. J.; Palumbo, A. V.; Steinman, A. D.; Huston, M. A.; Elwood, J. W. (1989). "Nutrient dynamics and food-web stability". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 20: 71–95. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.20.1.71. JSTOR 2097085.

- ^ Twiss, M. R.; Campbell, P. G. C.; Auclair, J. (1996). "Regeneration, recycling, and trophic transfer of trace metals by microbial food-web organisms in the pelagic surface waters of Lake Erie". Limnology and Oceanography. 41 (7): 1425–1437. Bibcode:1996LimOc..41.1425T. doi:10.4319/lo.1996.41.7.1425.

- ^ May, R. M. (1988). "How many species are there on Earth?" (PDF). Science. 241 (4872): 1441–1449. Bibcode:1988Sci...241.1441M. doi:10.1126/science.241.4872.1441. PMID 17790039. S2CID 34992724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-11. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ^ Beattie, A.; Ehrlich, P. (2010). "The missing link in biodiversity conservation". Science. 328 (5976): 307–308. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..307B. doi:10.1126/science.328.5976.307-c. PMID 20395493.

- ^ Ehrlich, P. R.; Pringle, R. M. (2008). "Colloquium Paper: Where does biodiversity go from here? A grim business-as-usual forecast and a hopeful portfolio of partial solutions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (S1): 11579–11586. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511579E. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801911105. PMC 2556413. PMID 18695214.

- ^ a b Dunne, J. A.; Williams, R. J.; Martinez, N. D.; Wood, R. A.; Erwin, D. H.; Dobson, Andrew P. (2008). "Compilation and Network Analyses of Cambrian Food Webs". PLOS Biology. 6 (4): e102. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060102. PMC 2689700. PMID 18447582.

- ^ a b Krause, A. E.; Frank, K. A.; Mason, D. M.; Ulanowicz, R. E.; Taylor, W. W. (2003). "Compartments revealed in food-web structure" (PDF). Nature. 426 (6964): 282–285. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..282K. doi:10.1038/nature02115. hdl:2027.42/62960. PMID 14628050. S2CID 1752696.

- ^ a b Bormann, F. H.; Likens, G. E. (1967). "Nutrient cycling" (PDF). Science. 155 (3761): 424–429. Bibcode:1967Sci...155..424B. doi:10.1126/science.155.3761.424. PMID 17737551. S2CID 35880562. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ^ a b Polis, G. A.; Anderson, W. B.; Hold, R. D. (1997). "Toward an integration of landscape and food web ecology: The dynamics of spatially subsidized food webs" (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 28: 289–316. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.28.1.289. hdl:1808/817. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ^ a b O'Neil, R. V. (2001). "Is it time to bury the ecosystem concept? (With full military honors, of course!)" (PDF). Ecology. 82 (12): 3275–3284. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[3275:IITTBT]2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25.

- ^ Gönenç, I. Ethem; Koutitonsky, Vladimir G.; Rashleigh, Brenda (2007). Assessment of the Fate and Effects of Toxic Agents on Water Resources. Springer. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-4020-5527-0.

- ^ Gil Nonato C. Santos; Alfonso C. Danac; Jorge P. Ocampo (2003). E-Biology II. Rex Book Store. p. 58. ISBN 978-971-23-3563-1.

- ^ Elser, J.; Hayakawa, K.; Urabe, J. (2001). "Nutrient Limitation Reduces Food Quality for Zooplankton: Daphnia Response to Seston Phosphorus Enrichment". Ecology. 82 (3): 898–903. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[0898:NLRFQF]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Paine, R. T. (1988). "Road maps of interactions or grist for theoretical development?" (PDF). Ecology. 69 (6): 1648–1654. Bibcode:1988Ecol...69.1648P. doi:10.2307/1941141. JSTOR 1941141. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ^ a b c Williams, R. J.; Berlow, E. L.; Dunne, J. A.; Barabási, A.; Martinez, N. D. (2002). "Two degrees of separation in complex food webs". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (20): 12913–12916. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9912913W. doi:10.1073/pnas.192448799. PMC 130559. PMID 12235367.

- ^ a b Banasek-Richter, C.; Bersier, L. L.; Cattin, M.; Baltensperger, R.; Gabriel, J.; Merz, Y.; et al. (2009). "Complexity in quantitative food webs". Ecology. 90 (6): 1470–1477. Bibcode:2009Ecol...90.1470B. doi:10.1890/08-2207.1. hdl:1969.1/178777. PMID 19569361.

- ^ Riede, J. O.; Rall, B. C.; Banasek-Richter, C.; Navarrete, S. A.; Wieters, E. A.; Emmerson, M. C.; et al. (2010). "Scaling of food web properties with diversity and complexity across ecosystems.". In Woodwoard, G. (ed.). Advances in Ecological Research (PDF). Vol. 42. Burlington: Academic Press. pp. 139–170. ISBN 978-0-12-381363-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2011-06-10.

- ^ Briand, F.; Cohen, J. E. (1987). "Environmental correlates of food chain length" (PDF). Science. 238 (4829): 956–960. Bibcode:1987Sci...238..956B. doi:10.1126/science.3672136. PMID 3672136. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ^ a b Neutel, A.; Heesterbeek, J. A. P.; de Ruiter, P. D. (2002). "Stability in real food webs: Weak link in long loops" (PDF). Science. 295 (550): 1120–1123. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.1120N. doi:10.1126/science.1068326. hdl:1874/8123. PMID 12004131. S2CID 34331654. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ Leveque, C., ed. (2003). Ecology: From ecosystem to biosphere. Science Publishers. p. 490. ISBN 978-1-57808-294-0.

- ^ a b Proctor, J. D.; Larson, B. M. H. (2005). "Ecology, complexity, and metaphor". BioScience. 55 (12): 1065–1068. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2005)055[1065:ECAM]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Strydom, Tanya; Dalla Riva, Giulio V.; Poisot, Timothée (2021). "SVD Entropy Reveals the High Complexity of Ecological Networks". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 9. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.623141. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ a b Dunne, J. A.; Williams, R. J.; Martinez, N. D. (2002). "Food-web structure and network theory: The role of connectance and size". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (20): 12917–12922. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9912917D. doi:10.1073/pnas.192407699. PMC 130560. PMID 12235364.

- ^ a b Capra, F. (2007). "Complexity and life". Syst. Res. 24 (5): 475–479. doi:10.1002/sres.848.

- ^ Peters, R. H. (1988). "Some general problems for ecology illustrated by food web theory". Ecology. 69 (6): 1673–1676. Bibcode:1988Ecol...69.1673P. doi:10.2307/1941145. JSTOR 1941145.

- ^ Michener, W. K.; Baerwald, T. J.; Firth, P.; Palmer, M. A.; Rosenberger, J. L.; Sandlin, E. A.; Zimmerman, H. (2001). "Defining and unraveling biocomplexity". BioScience. 51 (12): 1018–1023. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[1018:daub]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Bascompte, J.; Jordan, P. (2007). "Plant-animal mutualistic networks: The architecture of biodiversity" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38: 567–569. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095818. hdl:10261/40177. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2011-07-03.

- ^ Montoya, J. M.; Pimm, S. L.; Solé, R. V. (2006). "Ecological networks and their fragility" (PDF). Nature. 442 (7100): 259–264. Bibcode:2006Natur.442..259M. doi:10.1038/nature04927. PMID 16855581. S2CID 592403. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-06. Retrieved 2011-07-04.

- ^ Michio, K.; Kato, S.; Sakato, Y. (2010). "Food webs are built up with nested subwebs". Ecology. 91 (11): 3123–3130. Bibcode:2010Ecol...91.3123K. doi:10.1890/09-2219.1. PMID 21141173.

- ^ Montoya, J. M.; Solé, R. V. (2002). "Small world patterns in food webs" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 214 (3): 405–412. arXiv:cond-mat/0011195. Bibcode:2002JThBi.214..405M. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2001.2460. PMID 11846598. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-05. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- ^ Montoya, J. M.; Blüthgen, N; Brown, L.; Dormann, C. F.; Edwards, F.; Figueroa, D.; et al. (2009). "Ecological networks: beyond food webs". Journal of Animal Ecology. 78 (1): 253–269. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01460.x. hdl:10261/40154. PMID 19120606.

- ^ Shurin, J. B.; Gruner, D. S.; Hillebrand, H. (2006). "All wet or dried up? Real differences between aquatic and terrestrial food webs". Proc. R. Soc. B. 273 (1582): 1–9. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3377. PMC 1560001. PMID 16519227.

- ^ Egerton, F. N. "A history of the ecological sciences, part 6: Arabic language science: Origins and zoological writings" (PDF). Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 83 (2): 142–146.

- ^ Egerton, FN (2007). "Understanding food chains and food webs, 1700-1970". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 88: 50–69. doi:10.1890/0012-9623(2007)88[50:UFCAFW]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Shelford, V. (1913). "Animal Communities in Temperate America as Illustrated in the Chicago Region". University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Summerhayes, VS; Elton, CS (1923). "Contributions to the Ecology of Spitsbergen and Bear Island". Journal of Ecology. 11 (2): 214–286. doi:10.2307/2255864. JSTOR 2255864.

- ^ Hardy, AC (1924). "The herring in relation to its animate environment. Part 1. The food and feeding habits of the herring with special reference to the east coast of England". Fisheries Investigation London Series II. 7 (3): 1–53.

- ^ a b Elton, C. S. (1927). Animal Ecology. London, UK.: Sidgwick and Jackson. ISBN 978-0-226-20639-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Elton CS (1927) Animal Ecology. Republished 2001. University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Allee, W. C. (1932). Animal life and social growth. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company and Associates.

- ^ Stauffer, R. C. (1960). "Ecology in the long manuscript version of Darwin's "Origin of Species" and Linnaeus' "Oeconomy of Nature"". Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 104 (2): 235–241. JSTOR 985662.

- ^ Darwin, C. R. (1881). The formation of vegetable mould, through the action of worms, with observations on their habits. London: John Murray.

- ^ Worster, D. (1994). Nature's economy: A history of ecological ideas (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-521-46834-3.

- ^ Paine, RT (1966). "Food web complexity and species diversity". The American Naturalist. 100 (910): 65–75. doi:10.1086/282400. S2CID 85265656.

- ^ May RM (1973) Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Pimm SL (1982) Food Webs, Chapman & Hall.

Further reading

[edit]- Cohen, Joel E. (1978). Food webs and niche space. Monographs in Population Biology. Vol. 11. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. xv+1–190. ISBN 978-0-691-08202-8. PMID 683203.

- Fricke, Evan C.; Hsieh, Chia; et al. (2022). "Collapse of terrestrial mammal food webs since the Late Pleistocene". Science. 377 (6609): 1008–1011. Bibcode:2022Sci...377.1008F. doi:10.1126/science.abn4012. PMID 36007038. S2CID 251843290.

- "Aquatic Food Webs". NOAA Education Resources. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Food web

View on GrokipediaFundamentals of Food Webs

Definition and Basic Concepts

A food web is a complex network of feeding relationships among organisms in an ecosystem, illustrating who consumes whom through interconnected pathways of energy and nutrient transfer.[4] Unlike a food chain, which represents a linear, sequential path of consumption from producers to top predators, a food web captures the branching and overlapping interactions that reflect the multifaceted nature of ecological communities.[5] This network structure highlights how multiple food chains link together, allowing for alternative pathways that enhance ecosystem resilience.[6] The primary components of a food web include producers, consumers, and decomposers. Producers, or autotrophs such as plants and algae, form the base by converting solar energy into biomass through photosynthesis.[7] Consumers, which are heterotrophs, are categorized by their feeding habits: primary consumers (herbivores) feed directly on producers, secondary consumers (carnivores) prey on herbivores, and tertiary consumers occupy higher predatory roles.[5] Decomposers, including bacteria and fungi, break down dead organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the system for reuse by producers.[6] Food webs are organized around a trophic structure, where energy transfers from one level to the next, typically decreasing in efficiency at higher levels. Common complexities arise from omnivory, in which a single species consumes organisms from multiple trophic levels, and intraguild predation, where predators both compete for and consume the same prey species.[8] These interactions deviate from simple linear models and contribute to the stability and dynamics of the web. Trophic levels serve as the foundational building blocks for this structure.[4] A representative example of a simple terrestrial food web involves grasses and shrubs as producers, supporting herbivores like rabbits and deer (primary consumers), which are preyed upon by carnivores such as foxes and hawks (secondary and tertiary consumers), with decomposers like earthworms and bacteria processing waste and remains to sustain soil fertility.[9] This interconnected setup demonstrates how disruptions in one link, such as herbivore overpopulation, can ripple through the network, affecting predators and nutrient availability.[10]Role in Ecosystems

Food webs play a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem stability by providing redundancy and alternative pathways that buffer against perturbations, such as species loss, thereby preventing trophic cascades that could destabilize the entire system. Complex network structures in food webs enhance persistence and resistance to disturbances through diverse interaction pathways, allowing ecosystems to recover from events like predator removal or prey overexploitation. For instance, in diverse aquatic systems, structural asymmetry in trophic interactions contributes to long-term stability by distributing risks across multiple species levels. Food webs support biodiversity by fostering species coexistence through intricate linkages that reduce competitive exclusion and increase resilience to environmental disturbances. Higher trophic diversity within food webs promotes multifunctionality, enabling more species to persist amid fluctuating conditions like habitat fragmentation. This diversity in connections, such as predator-prey and mutualistic ties, enhances overall ecosystem resilience, as seen in terrestrial and marine habitats where varied food web topologies sustain higher species richness. Food webs underpin key ecosystem services, including nutrient retention by facilitating efficient cycling through trophic levels, pollination via plant-pollinator interactions embedded in broader networks, and natural pest control through predator-prey dynamics that regulate herbivore populations. In agricultural landscapes, intact food webs support agricultural sustainability by maintaining balanced populations of prey and predators, ensuring long-term productivity. These services arise from the interconnected nature of food webs, which integrate multiple trophic processes to deliver benefits like soil fertility and crop protection. Disruptions in food web structure serve as indicators of ecosystem health, signaling underlying environmental changes such as pollution or climate shifts that alter species interactions and abundances. For example, shifts in marine food web metrics, like changes in trophic indices, have been used to detect overfishing impacts and habitat degradation under frameworks like the Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Monitoring these disruptions allows early detection of stressors, guiding conservation efforts to restore balance. The integrity of food webs has direct implications for human activities, particularly in agriculture and forestry, where maintaining web complexity supports food security by enhancing pollination, pest regulation, and soil health services essential for crop yields. In agroecosystems, disruptions from intensification can cascade through food webs, reducing biodiversity and services that underpin sustainable production and global food supplies. Preserving food web structure is thus vital for resilient agricultural and forestry practices that secure long-term human well-being.Structural Components

Trophic Levels

Trophic levels represent the hierarchical positions of organisms within a food web based on their primary mode of nutrient acquisition, forming the foundational structure for understanding energy and matter transfer in ecosystems. The base level, trophic level 1, consists of primary producers such as plants, algae, and phytoplankton, which convert solar energy into biomass through photosynthesis or chemosynthesis. Trophic level 2 comprises primary consumers, primarily herbivores that feed directly on producers, while higher levels (3 and beyond) include secondary consumers (carnivores preying on herbivores), tertiary consumers, and apex predators that occupy the top positions. Decomposers, including bacteria and fungi, operate outside this strict numbering as they break down dead organic matter, recycling nutrients but not fitting neatly into the consumer hierarchy. This classification, originally conceptualized in the context of aquatic ecosystems, emphasizes the sequential flow from autotrophs to heterotrophs. In complex food webs, discrete integer trophic levels often prove insufficient due to the prevalence of omnivory and generalist feeding strategies, leading to the adoption of fractional trophic levels. For instance, an omnivore that consumes both producers and herbivores might occupy a fractional position such as 2.5, calculated as a weighted average of the trophic levels of its prey. This approach accounts for dietary breadth, where the trophic level for species is determined by , with representing the fraction of prey 's biomass in the diet of . Such fractional assignments reveal that in real ecosystems, many species—particularly at lower levels—exhibit mixed feeding, blurring strict boundaries.[11] Despite their utility, trophic levels face limitations in capturing the full complexity of food webs, particularly from omnivory, detritivory, and feedback loops that create non-linear interactions. Analysis of diverse food webs shows that only about 54% of species can be unambiguously assigned to integer levels, with omnivory predominantly affecting the lowest three levels and detritivores complicating producer-consumer distinctions through their reliance on decaying matter. Loop systems, where predators also consume lower-level resources, further erode the hierarchical model, highlighting that real-world feeding relations are reticulate rather than strictly vertical. These challenges underscore the need for nuanced representations beyond simple leveling.[12] Empirical measurement of trophic levels relies heavily on stable isotope analysis, which provides a time-integrated assessment of dietary history. Nitrogen isotopes () increase predictably by 3–4‰ per trophic step due to fractionation during assimilation, allowing estimation of an organism's position relative to basal resources, while carbon isotopes () trace the origin of primary production (e.g., pelagic vs. benthic sources) with minimal enrichment (0–1‰ per level). This method has been validated across aquatic and terrestrial systems, enabling precise assignment even for omnivores through mixing models. For example, in a temperate lake ecosystem, phytoplankton occupy level 1 with low values, zooplankton at level 2 show enrichment of approximately 3.5‰, and planktivorous fish at level 3 exhibit further increases, illustrating the gradient empirically.083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2)[13]Food Chains and Linkages

A food chain represents a linear sequence of organisms in an ecosystem where each member consumes the preceding one, transferring nutrients and energy from producers to higher-level consumers.[5] Typically, these sequences begin with producers such as plants or algae that capture solar energy through photosynthesis, followed by primary consumers like herbivores, secondary consumers such as carnivores, and sometimes tertiary consumers or apex predators.[14] Food chains are classified into types including grazing chains, which start with living plant material; detrital chains, involving decomposers processing dead organic matter; and parasitic chains, where parasites derive sustenance from living hosts within the grazing or detrital pathways.[15] These linear pathways form the foundational building blocks of more complex food webs, illustrating direct predator-prey relationships. In food webs, individual food chains interconnect through directed linkages, where energy flows unidirectionally from prey to predator, creating a network topology.[16] Connectance measures the proportion of realized feeding links relative to all possible links among species, often ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 in empirical webs, indicating the density of interactions.[17] Linkage density, defined as the average number of links per species, quantifies the overall connectivity and typically increases with species richness, reflecting how extensively organisms exploit resources. These metrics highlight the web's structure, where trophic levels—positions along chains from basal producers to top predators—emerge from the aggregation of these linkages.[7] The complexity of food webs arises from branching and convergence in these linkages: branching occurs when a single predator consumes multiple prey species, increasing out-degree in network terms, while convergence happens when multiple predators feed on the same prey, elevating in-degree.[18] Such patterns, where predators exhibit generality through diverse diets and prey face vulnerability from various consumers, prevent webs from remaining simple linear chains and instead foster intricate topologies that enhance stability and resilience.[19] Food chain lengths vary across ecosystems, with shorter chains (often 2-3 links) prevalent in simple or resource-limited environments and longer ones (up to 5 or more) in diverse, productive systems that support more trophic levels.[20] Empirical studies indicate an average chain length of approximately 3-5 trophic levels in most natural food webs, limited by factors like energy dissipation and species interactions.[21] For instance, in marine ecosystems, a typical grazing food chain progresses from phytoplankton and algae (producers) to zooplankton (primary consumers), small fish (secondary consumers), larger predatory fish, and ultimately apex predators like sharks.[13]Ecological Pyramids

Ecological pyramids are graphical models that represent the trophic structure of an ecosystem by quantifying the relative abundance of organisms, their biomass, or the energy at successive trophic levels, typically with producers at the base and top predators at the apex. These diagrams, first conceptualized as pyramids of numbers by Charles Elton in his 1927 book Animal Ecology, provide a visual summary of how resources diminish as energy moves through the food web, emphasizing the decreasing availability from lower to higher trophic levels. The pyramid of numbers illustrates the count of individual organisms at each trophic level, showing a general decrease upward due to the larger populations required to support fewer consumers at higher levels; for instance, in a terrestrial ecosystem, thousands of insects may serve as prey for hundreds of birds, which in turn support a handful of predators. The pyramid of biomass depicts the total mass of living organisms per trophic level, measured in units like grams per square meter, which can reveal standing crop sizes but may vary in shape depending on ecosystem dynamics. The pyramid of energy, often expressed as the rate of energy flow (e.g., kilocalories per square meter per year), always forms an upright structure because energy diminishes progressively, with only a fraction transferred between levels. These pyramids are constructed using field data, such as direct counts for numbers, wet or dry weight measurements for biomass, and calorimetric or productivity estimates for energy, often collected through sampling methods like quadrats or net hauls in specific habitats.[22][23] A key principle underlying the shape of these pyramids, particularly the energy pyramid, is Lindeman's approximation of trophic transfer efficiency, which posits that approximately 10% of the energy from one trophic level is transferred to the next, with the remainder lost primarily as heat through respiration and other processes; this "10% rule," derived from empirical data on aquatic systems, explains the exponential decline in available energy and thus the pyramidal form. Inverted pyramids can occur, however, especially for biomass: in oceanic ecosystems, the biomass pyramid is often inverted because phytoplankton producers have low standing biomass due to their rapid turnover rates (high productivity but short lifespans), while zooplankton consumers maintain higher biomass supported by continuous production. By contrast, a forest ecosystem typically exhibits an upright pyramid of numbers, with abundant primary producers and herbivores like insects vastly outnumbering sparse top carnivores such as eagles.[22][23][24] Despite their utility in visualizing trophic organization, ecological pyramids have notable limitations, as they assume a steady-state ecosystem without accounting for temporal fluctuations in population sizes or seasonal variations in productivity. They also overlook detrital pathways, where much of the organic matter enters the food web through decomposers rather than direct grazing, potentially underrepresenting microbial contributions. Additionally, these models simplify complex food webs by focusing on linear trophic levels, ignoring omnivory or species occupying multiple levels, which can lead to misleading representations in dynamic or diverse systems.[25][26]Functional Dynamics

Energy Flow and Transfer

Energy enters food webs primarily through primary production, where autotrophs such as plants and algae capture solar energy via photosynthesis, or in certain environments like deep-sea hydrothermal vents, through chemosynthesis using chemical energy from inorganic compounds.[22][27] This energy flows unidirectionally through successive trophic levels, from producers to herbivores, carnivores, and higher-order consumers, in accordance with the first and second laws of thermodynamics.[28] Unlike nutrients, which can cycle, energy cannot be recycled and is progressively dissipated as heat through metabolic processes at each transfer.[29] The foundational equation for primary production distinguishes gross primary production (GPP), the total energy fixed by autotrophs, from net primary production (NPP), the energy available to the rest of the ecosystem after accounting for autotrophic respiration:where represents autotrophic respiration.[30] This NPP forms the energy base for higher trophic levels, with subsequent transfers governed by trophic efficiency, where production at the next level () is a fraction of ingestion at the current level ():

Here, is the transfer efficiency, typically ranging from 0.1 to 0.2 (10-20%), as formalized in Lindeman's trophic-dynamic model.[22][31] These efficiencies reflect production-to-biomass conversion factors, where only a portion of ingested energy is assimilated into consumer biomass.[32] Energy losses occur primarily through respiration, which releases heat during metabolism; egestion, the undigested waste excreted as feces; and mortality, where uneaten deaths contribute to detritus rather than direct transfer.[33] These mechanisms ensure that standing crop—the biomass present at any time—remains lower than throughput, the total energy flowing through the system over time, limiting the length and productivity of food webs.[22] Respiration alone accounts for the majority of losses, often 60-90% at each level, enforcing the observed 10-20% transfer rule.[32] Transfer efficiencies vary by pathway; for instance, microbial loops in aquatic systems exhibit higher efficiencies (up to 30-50% in some bacterial-protozoan transfers) due to rapid turnover and direct carbon channeling to higher consumers like zooplankton.[34] In contrast, food chains involving large mammals, such as predator-prey dynamics in terrestrial ecosystems, show lower efficiencies (often below 10%) owing to greater metabolic demands, longer generation times, and higher respiration losses in endothermic organisms.[35] These differences highlight how pathway structure influences overall energy flow and ecosystem productivity.[36]