Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

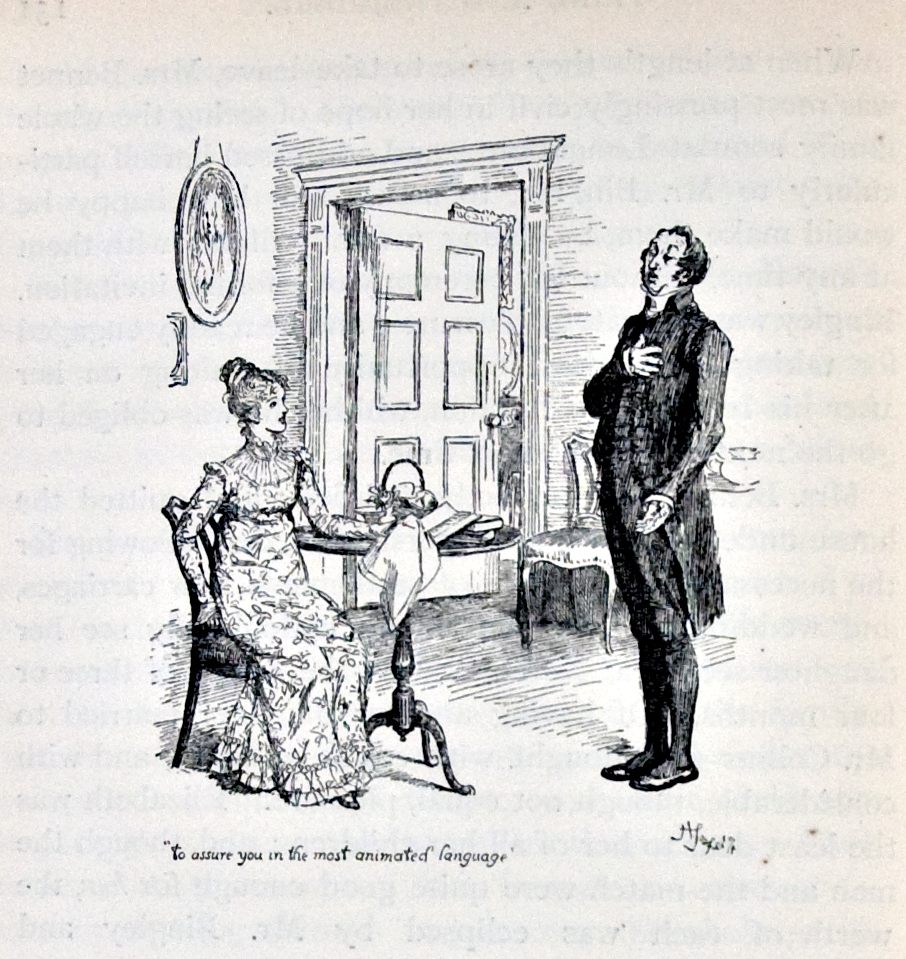

Mr William Collins

View on Wikipedia| Mr William Collins | |

|---|---|

| Jane Austen character | |

Mr Collins proposes to Elizabeth Bennet. | |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Relatives |

|

| Home | Hunsford, Kent |

Mr William Collins is a fictional character in the 1813 novel Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen. He is a distant cousin of Mr Bennet, a clergyman and holder of a valuable living at the Hunsford parsonage near Rosings Park, the estate of his patroness Lady Catherine De Bourgh, in Kent. Since Mr and Mrs Bennet have no sons, Mr Collins is also the heir presumptive to the Bennet family estate of Longbourn in Meryton, Hertfordshire, due to the estate being entailed to heirs male.[1] Mr Collins is first introduced during his visit to Longbourn.

Background

[edit]Mr William Collins, 25 years old when the novel begins, is Mr Bennet's distant cousin, a clergyman, and the presumptive inheritor of Mr Bennet's estate of Longbourn. The property is entailed to male heirs, meaning that Mr Bennet's daughters and their issue cannot inherit after Mr Bennet dies. Unless Mr Bennet has a son (which he and Mrs Bennet have no expectation of), the estate of £2,000-per-annum will pass to Mr Collins.[2]

Born to a father who is described as "illiterate and miserly", the son, William, is not much better. The greatest part of his life has been spent under the guidance of his father (who dies shortly before the beginning of the novel). The result is a younger Collins who is "not a sensible man, and the deficiency of nature had been but little assisted by education or society": having "belonged to one of the universities" (either Oxford or Cambridge), he "merely kept the necessary terms, without forming at it any useful acquaintance", nor accomplishments. So despite his time spent in university, his view of the world is apparently scarcely more informed or profound than Mrs Bennet's (a fact that would cast doubts upon the perspicuity of the Bishop who oversaw Mr Collins's ordination, in the eyes of the reader). His manner is obsequious and he readily defers to and flatters his social superiors. He is described as a "tall, heavy looking young man of five and twenty. His air was grave and stately, and his manners were very formal".

Austen writes that his circumstances in early life, and the "subjection" in which his father had brought him up, had "originally given him great humility of manner". However, this characteristic has been "now a good deal counteracted by the self-conceit of a weak head, living in retirement", altered greatly and been replaced with arrogance and vanity due to "early and unexpected prosperity".[3] This early prosperity came, by chance, at the hands of Lady Catherine de Bourgh, when a vacancy arose for the living of the Hunsford parish, "and the respect which he felt for her high rank and his veneration for her as his patroness, mingling with a very good opinion of himself, of his authority as a clergyman, and his rights as a rector, made him altogether a mixture of pride and obsequiousness, self-importance and humility". He has a ridiculously high regard for Lady Catherine and her daughter, of whom he is "eloquent in their praise".[4]

Elizabeth's rejection of Mr Collins's marriage proposal is welcomed by her father, regardless of the financial benefit to the family of such a match. Mr Collins then marries Elizabeth's friend Charlotte Lucas. Mr Collins is usually considered to be the foil to Mr Darcy, who is grave and serious, and acts with propriety at all times. On the other hand, Mr Collins acts with impropriety and exaggerated humility, which offers some comedic relief. He likes things, especially if they are expensive or numerous, but is indifferent to true beauty and value ("Here, leading the way through every walk and cross walk, and scarcely allowing them an interval to utter the praises he asked for, every view was pointed out with a minuteness which left beauty entirely behind. He could number the fields in every direction, and could tell how many trees there were in the most distant clump"[5]).

Portrayal

[edit]

Mr Collins is first mentioned when Mr Bennet tells his wife and family that his cousin will be visiting them. Mr Bennet reads them a letter sent by Mr Collins in which he speaks of making amends for any past disagreements between his father and Mr Bennet. In his letter, it is clear that Mr Collins readily assumes that his overtures of peace will be gratefully accepted, and further presumes upon the family as to announce that he will come stay with them for a week, without even first asking for permission.

On the first night of his visit, he spends time dining with the family and reading to them from Fordyce's Sermons in their parlour. It is at this point that Mr Collins seems to take a fancy to the eldest daughter, Jane. When discussing his intentions with Mrs Bennet he is told that Jane may very soon be engaged.[3] It takes Mr Collins only a few moments to redirect his attentions to Elizabeth Bennet, whom he believes in "birth and beauty"[3] equals her sister.

He spends the rest of his stay making visits around the neighbourhood with the Bennet sisters, minus Mary. They visit Mrs Phillips, Mrs Bennet's sister. Mr Collins is quite charmed by this encounter and seems extremely pleased to be treated so well by the family. He continues to pay specific attention to Elizabeth.

Collins first gives Elizabeth a hint of his intentions prior to the Netherfield ball hosted by Charles Bingley. He asks Elizabeth if she will allow him the pleasure of being her partner for the first two dances.[6] Though Mr Collins quite enjoys himself during these dances, Elizabeth does not. Elizabeth has a strong aversion to Mr Collins. However, she usually tries to avoid any conversation beyond what is polite and proper. At the Netherfield ball, she describes her dances with Mr Collins as "dances of mortification". She comments that Mr Collins acts awkwardly and solemnly, and gives her "all the shame and misery which a disagreeable partner for a couple of dances can give".[6]

At the end of Mr Collins's week-long visit he seeks a private audience with Elizabeth. Oblivious to Elizabeth's feelings, he tells her that "almost as soon as he entered the house, he singled her out as the companion of his future life". He also expounds upon his reasons for getting married:

- He feels that every clergyman should set the example of matrimony in his parish.

- He believes it will add to his own personal happiness.

- Lady Catherine has urged him to find a wife as quickly as possible.[7]

Mr. Collins, you must marry. A clergyman like you must marry. Choose properly, choose a gentlewoman for my sake; and for your own, let her be an active, useful sort of person, not brought up high, but able to make a small income go a good way. This is my advice. Find such a woman as soon as you can, bring her to Hunsford, and I will visit her.

Mr Collins declares himself to be "violently in love" with Elizabeth; Elizabeth, however, knows that his professed feelings for her are completely imaginary and that they are a complete mismatch, but all of her attempts to dissuade him have been too subtle for him to recognise. When Elizabeth rejects his proposal, Collins is quite taken aback and does not believe she is serious. Elizabeth has to tell him firmly that she is in fact serious. Mr Collins seems surprised and insulted. He had not considered that his proposal would ever be undesirable. He says that Elizabeth is only pretending to reject his repeated proposals to be coy as a means to stoke his desires for her.

I am not now to learn, replied Mr. Collins, with a formal wave of the hand, that it is usual with young ladies to reject the addresses of the man whom they secretly mean to accept, when he first applies for their favour; and that sometimes the refusal is repeated a second, or even a third time. I am therefore by no means discouraged by what you have just said, and shall hope to lead you to the altar ere long.

Elizabeth has to repeat to Mr Collins that she does not intend to marry him since he believes she is really only trying to behave with propriety by refusing him. Collins only accepts her refusal once Mrs Bennet admits that it is not likely that Elizabeth intends changing her mind. Mrs Bennet goes to Mr Bennet; she wants him to force Elizabeth to accept him because Elizabeth has great respect for her father. Mr Bennet says that if she accepts Mr Collins, he will refuse to see her.

A few days after this rejection, Mr Collins's sentiments are transferred to Elizabeth's friend, Charlotte Lucas, who encourages his regard. Since Collins has very good prospects, Charlotte is determined to gain his favour.[8] Her plan works well: a few days after this, Elizabeth hears that Charlotte is now engaged to Mr Collins. Upon hearing this news from Charlotte herself, Elizabeth declares it to be "impossible" and wonders how it is that someone could find Mr Collins less than ridiculous, let alone choose to marry him. This engagement takes place quickly and later Mr Collins comes to visit the Bennets with his new wife to pay their respects.

A few months later Elizabeth is invited to visit Charlotte at her new home in Hunsford. Later on, he seems intent on convincing the Bennets that his pride was never injured and that he never had intentions towards Elizabeth (almost acting as if he was the one who rejected her), or any of her sisters.[9]

In her visit to Hunsford, Elizabeth it able to see how Mr Collins behaves with Lady Catherine de Bourgh; and is shocked; "Elizabeth soon perceived, that though this great lady was not in the commission of the peace for the county, she was a most active magistrate in her own parish, the minutest concerns of which were carried to her by Mr. Collins; and whenever any of the cottagers were disposed to be quarrelsome, discontented, or too poor, she sallied forth into the village to settle their differences, silence their complaints, and scold them into harmony and plenty." Meddling in the business of the Overseers of the Poor and the Justices of the Peace are actions of gross impropriety on Lady Catherine's behalf; and Mr Collins's facilitating these actions through retailing to her information given to him by parishoners in confidence amounted to a serious betrayal of trust. Subsequently, of course, Mr Collins will similalry abuse information given in confidence, in sharing with Lady Catherine the contents of a private letter apparently addressed to Charlotte.

Mr Collins appears in the novel only a few more times, usually via letters. After Lydia Bennet elopes with Mr Wickham he sends a letter of consolation to Mr Bennet, in which his sympathetic tone is confusingly contrasted with his advice to cast Lydia out of the family lest her disgrace reflects on the rest of the family. His deference to Lady Catherine leads him to show her a confidential letter addressed to his wife Charlotte, which provided some details of the "patched-up business" by which Wickham had been pursuaded to make an honest woman of Lydia; while also suggesting that Mr Darcy and Elizabeth might soon become engaged. This causes Lady Catherine to travel to Meryton to demand Elizabeth end her relationship with Darcy and plays a significant role in the sequence of events that leads to Darcy and Elizabeth's engagement. At the end of the novel, Lady Catherine's fury at the engagement leads Collins and Charlotte, who is by now expecting a child, to take an extended visit to Charlotte's parents until they can no longer be the targets of her rage.

Extra-textual information

[edit]Some scholarly analysis has been conducted on Austen's characterisation of Mr Collins. Possibly the most thorough examination of this character was made by Ivor Morris in his book Mr Collins Considered: Approaches to Jane Austen. Morris says "there is no one quite like Mr Collins [...] his name has become a byword for a silliness all of his own—a felicitous blend of complacent self-approval and ceremonious servility."[10] He continues to say that Austen designed Mr Collins as a flat character, yet he is one of her great accomplishments. Morris suggests that though Mr Collins has few dimensions, he is just as rounded as Sense and Sensibility's Edward Ferrars and Colonel Brandon, or Emma's Mr Knightley and Harriet Smith.[11]

In another analysis, Deirdre Le Faye wrote "what does make Mr Collins a figure of fun and rightful mockery is his lack of sense, of taste, and of generosity of spirit contrasted to his own supreme unawareness of his shortcomings in these respects".[12] He has also been criticised for taking such a casual view of his own marriage, which is one of the primary concerns of the Church.[13]

A book review written by Dinah Birch, a professor at the University of Liverpool, examines the role of Mr Collins as a clergyman in Jane Austen's writing. Birch says that "one of the strongest points of Pride and Prejudice is its understanding that Jane Austen's Christianity ... is also an imaginative force in her writing", because Austen is "deeply interested in the role of the church", in her society.[14] She writes about the lack of religious dedication she sees in some clergymen through her character Mr Collins who is "by no means an aspirant to sainthood".[15]

Eponym

[edit]The text of Pride and Prejudice includes the following passage: "The promised letter of thanks from Mr Collins arrived on Tuesday, addressed to their father, and written with all the solemnity of gratitude which a twelve-month's abode in the family might have prompted."

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a "Collins" as "a letter of thanks for entertainment or hospitality, sent by a departed guest," and identifies this usage as a reference to Austen's Mr Collins.[16] The OED entry traces the usage to 1904, citing its appearance in Chambers's Journal. The specific context is a piece by etiquette writer Katharine Burrill, who opines that Collins's "letters are monuments of politeness and civility."[17]

Depictions in other media

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Actor | Role | Film | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Melville Cooper | Mr William Collins | Pride and Prejudice | |

| 2003 | Hubbel Palmer | William Collins | Pride & Prejudice: A Latter-Day Comedy | Modern adaptation of Pride and Prejudice |

| 2004 | Nitin Ganatra | Mr Kholi | Bride and Prejudice | A Bollywood-style adaptation of Pride and Prejudice |

| 2005 | Tom Hollander | Mr William Collins | Pride & Prejudice | |

| 2016 | Matt Smith | Parson Collins | Pride and Prejudice and Zombies | Based on the parody novel by Seth Grahame-Smith. |

Television

[edit]| Year | Actor | Role | Television Program | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Lockwood West | Mr Collins | Pride and Prejudice | Television mini-series |

| 1967 | Julian Curry | Mr Collins | Pride and Prejudice | |

| 1980 | Malcolm Rennie | Mr Collins | Pride and Prejudice | |

| 1995 | David Bamber | Mr Collins | Pride and Prejudice | |

| 2008 | Guy Henry | Mr Collins | Lost in Austen | A fantasy adaptation of Pride and Prejudice |

| 2012 | Maxwell Glick | Ricky Collins | The Lizzie Bennet Diaries | A web series, modernized adaptation of Pride and Prejudice |

| TBA | Jamie Demetriou | Mr William Collins | Pride and Prejudice | Television mini-series |

References

[edit]- ^ Rossdale, P. S. A. (1980). "What Caused the Quarrel Between Mr Collins and Mr Bennet – Observations on the Entail of Longbourn". Notes and Queries. 27 (6): 503–504. doi:10.1093/nq/27.6.503.

- ^ "Pride & Prejudice & Entailed land". Heirs & Successes. 25 October 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Austen, Jane (1984). Pride and Prejudice. US: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. Chapter 15.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1984). Pride and Prejudice. US: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. Chapter 13.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1995). Pride and Prejudice. New York: Modern Library. p. 115.

- ^ a b Austen, Jane (1984). Pride and Prejudice. US: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. Chapter 18.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1984). Pride and Prejudice. US: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. Chapter 19.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1984). Pride and Prejudice. US: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. Chapter 22.

- ^ Austen, Jane (1984). Pride and Prejudice. US: The Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. Chapter 28.

- ^ Morris, Ivor (1987). Mr. Collins Considered: Approaches to Jane Austen. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. Chapter 1: Query.

- ^ Morris, Ivor (1987). Mr Collins Considered. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. Chapter 1: Query.

- ^ Le Faye, Deirdre (May 1989). "Mr. Collins Considered: Approaches to Jane Austen by Ivor Morris". The Review of English Studies. 40 (158): 277–278.

- ^ Reeta Sahney, Jane Austen's heroes and other male characters, Abhinav Publications, 1990 ISBN 9788170172710 p.76

- ^ Birch, Dinah (1988). "Critical Intimacies". Mr-Collins Considered- Approaches to Austen, Jane- Morris, I. 37 (158): 165–169.

- ^ Morris, Ivor (1987). Mr Collins Considered: Approaches to Jane Austen. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. Chapter 1: Query.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "Collins (n.2)," July 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/1085984454

- ^ Burrill, Katharine (27 August 1904). "Talks with Girls: Letter-Writing and Some Letter-Writers". Chambers's Journal. 7 (352): 611.